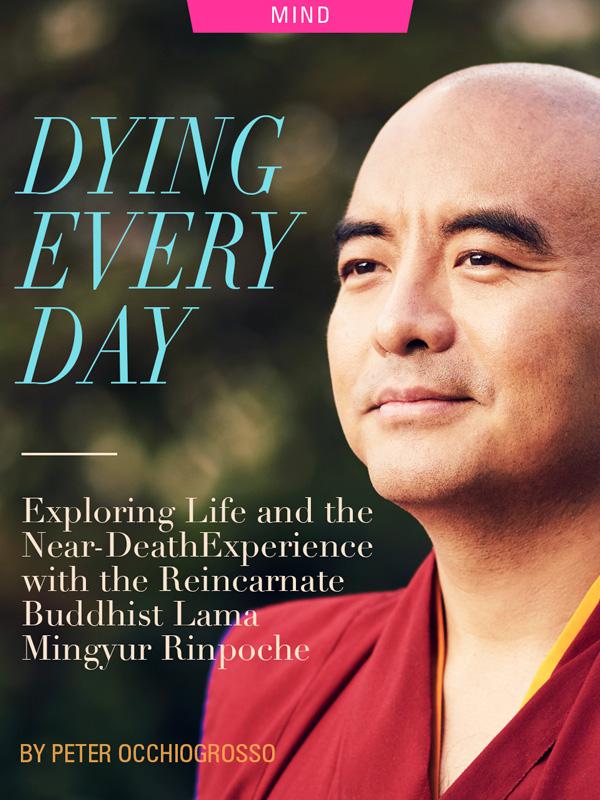

Dying Every Day: Exploring Life and the Near-Death Experience with Reincarnate Buddhist Lama Mingyur Rinpoche

A discussion with a modern day lama who breaks with tradition in his journey of self-discovery that includes an anonymous wandering retreat and a near-death experience

_______

“How many of you did not understand anything I just said? Please raise your hands.”

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is addressing a crowd of 200 people in an auditorium on the campus of St. Thomas University, a Catholic college located in a residential area of St. Paul, Minnesota. On the second day of the Path of Liberation retreat that I’m attending, he has just spent more than an hour attempting to explain a profoundly subtle concept of meditation often called “nature of mind.” One reason I came all this way to spend a week with Mingyur and his team of master instructors was to learn how to recognize the nature of mind, a key to practicing Mahamudra, the highest level of meditative awareness in Tibetan Buddhism.

Still in his mid-forties, Mingyur Rinpoche is already one of the most popular, and most highly respected, teachers in the world of Tibetan Buddhism—a world that presents a Buddhism that, some Buddhists might argue, diverges from the teachings that the Buddha himself propounded some 2,500 years ago in northern India and what is now Nepal. Although the historical figure of Shakyamuni Buddha taught a way of life that relies entirely on one’s own human efforts, the Vajrayana tradition in which Mingyur and his fellow Tibetans work is replete with deities and celestial beings, male and female, although nothing quite like the Supreme Being of the Western Abrahamic faiths.

The Buddha did accept the gods and demigods of the Indic culture of his day, but believed them to be inferior to the human realm because only humans can become enlightened. Most Western followers now view Tibetan deities like Chenrezig, the bodhisattva of compassion, as metaphors for states of consciousness rather than actual beings, but the line can get blurry at times.

One key element of Tibetan Buddhism, however, is uniquely in touch with Western culture, both the aging baby boom generation of Americans now in their sixties and seventies and the Millennials, who are watching their futures go up in smoke:

None of the world’s major religious traditions has focused more of its teachings on the dying process, an event that looms larger than ever for many of us.

And yet, far from reflecting a morose obsession with the end of physical life, the Tibetans offer some of the most practical, empirical aids not only for seeing death as a positive experience, but also for learning how to undergo it with the least suffering and the greatest opportunity for transformation as consciousness continues in its next stage. An advanced practice known as phowa, for instance, designed to teach practitioners how to direct the transference of consciousness at the time of death, either for oneself or another, has virtually no counterpart in other religious traditions, nor in modern science, for that matter.

Even if you don’t believe in an afterlife or rebirth, simply knowing how to die consciously and without mind-clouding drugs can clearly be beneficial.

Even more to the point, the Tibetan view of the dying process also aligns closely with our current understanding of the near-death experience, or NDE, which has become a subject of intense interest in recent years. The Tibetan Book of the Dead—also known by its original Tibetan title of the Bardo Thodol, or “Liberation through Listening in the Between”—is the most popular of all the books in the Tibetan canon among Westerners.

Perhaps no sacred text more thoroughly explicates the process one’s consciousness goes through during and immediately after dying. Dr. Raymond Moody, whose 1975 classic Life After Life introduced the term near-death experience, and became a bestseller, was aware ofthe Bardo Thodol, which had been first translated into English in 1927. Moody found it astonishingly cognate with the one hundred or so NDEs he had been documenting. “The book contains a lengthy description of the various stages through which the soul goes after physical death,” he wrote in Life After Life. “The correspondence between the early stages of death which it relates and those which have been recounted to me by those who have come near to death is nothing short of fantastic.”

The goal of that text is to help readers recognize and navigate the several , or “in-between” states during which the possibility of achieving enlightenment, or liberation from the wheel of suffering known as , is greatly heightened. Composed in the 8th century by the Buddhist adept Padmasambhava, whose was discovered and revealed some six centuries later and has been recently translated into English any number of times.

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days