Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Luiz Otávio Barros - Critique of Task-Based Learning

Încărcat de

Luiz Otávio Barros, MATitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Luiz Otávio Barros - Critique of Task-Based Learning

Încărcat de

Luiz Otávio Barros, MADrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Lancaster University

Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages

MA in Applied Linguistics for ELT

Communicative and Pedagogical Grammar –

November 1998

Luiz Otavio de Barros Souza

luizotaviobarros@gmail.com

Queries from a Task-Based Teacher Trainer1

Oh no! Not the Present Perfect again! We do it four times already!

Most language teachers at some point in their careers will have had the

distressingly familiar experience of having exposed students to a new

language structure and witnessed near-perfect performance in formal

practice (in its broadest sense), just to discover that students were

subsequently unable to proceduralise the same language in other real

situations. This lack of transfer from the language lesson to natural

language use contexts has always been a major source of professional

concern for me, particularly so in the late 80s, when I was relatively

inexperienced in ELT. Still blissfully unaware of the role played by other

key elements such as attitude, aptitude and cognitive style, I was soon

drawn to the conclusion that the methodology was obviously flawed in

some way.

Needless to say, the flawed methodology was the so-called PPP

paradigm2, a framework for grammar instruction organised around

three linear phases: presentation of a new structure, followed by

manipulative practice and then freer production. My initial assumption

that there was something wrong with the 3Ps approach received ample

corroborative evidence from an impressive body of research (to be

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 1

described later) that not only discredited the theoretical rationale

underlying PPP, but also seemed to advocate an alternative model of

instruction: Task-Based Learning.

Almost fifteen years have gone by since the first experiments with Task-

Based Instruction (Willis J. 1996a: 52) and it has gained increased

respect amongst several scholars (Breen 1989; Crookes 1986; Duff

1986; Long 1985; Nunan 1989 cited by Kumaravadivelu 1993: 69).

Similarly, the theory underlying a PPP model seems to enjoy as little

credibility in academic circles as it did then. And yet, the PPP approach

is still arguably the most widely used framework for the teaching of

grammar. In a recent interview, Ellis made this point quite forcefully:

It seems to me that there’s plenty of evidence that we can do

PPP until we’re blue in the face, but it doesn’t necessarily

result in what PPP was designed to do. And yet there’s still,

within language teaching, a commitment to trying to control

not only the input but actually what is learned. (Ellis 1993,

cited by Willis D. 1996: 46)

This “resistance to change” has often been attributed to a number of

factors. While some would claim that PPP perpetuates the teacher’s

comfort zone by sustaining classroom power relations and providing

accountability (Skehan 1996: 18), others tend to lay the blame on

teacher trainers and textbook writers (Lewis 1993: 188-192). However,

it is my belief that valid as these arguments are, they do not provide us

with the whole picture. Luiz Otavio Barros.

From 1995 to 1998 I accompanied the evolution of a small-scale

“paradigm shift” project in a large EFL institute in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

The goal of the project was to implement Task-Based Learning

(hereafter referred to as TBL) at intermediate level. At least 200 teachers

(quite heterogeneous in terms of experience and professional profile)

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 2

were directly involved. Having spent at least 50 hours observing lessons

and doing one-to-one tutorials, I was provided with convincing evidence

that grappling with the tenets and technicalities of TBL was an

extremely difficult and often frustrating experience for most of those

teachers. Though at first glance one might put it down to a clash of

beliefs about how languages should be learned, things are not nearly as

simple. Arguably, the “clash of beliefs” hypothesis might have been the

case in the earlier days of TBL, when formal instruction was usually

dismissed out hand (as we will soon see). However, in the

aforementioned project the exact opposite was true. All training efforts

were directed at combining the tenets of TBL with a focus on grammar.

Nonetheless, what eventually became apparent was that most of the

ensuing principles and classroom techniques were generally perceived

to be of limited pragmatic utility, ambivalent and difficult to

comprehend. Perhaps this perception was justified:

Little theoretical work has been done in tying grammar pedagogy

and task-based methodology together. (Loschky and Bley-

Vroman 1993:123)

In this paper I will survey the work that has been done in that area and

tentatively imply that the problems I described above are to some extent

related to the current state of affairs in TBL pedagogy. I will begin by

examining the grounds on which a PPP methodology was discredited in

the mid 1980s (and TBL advocated). Then I move on to describe TBL in

the 90s and the research findings that lent support to a comeback of

grammar instruction. What follows is an overview of recent attempts to

integrate grammar and TBL. Luiz Otavio Barros.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 3

PART 1

A Under attack

When one examines the literature, one is overwhelmed by the amount

of criticism the PPP model has come in for in recent years (Long1990;

Prabhu1987; Skehan1998; Willis J. 1996b). It is commonly argued, for

example, that PPP necessarily restricts exposure to language and

therefore reduces the scope for comprehensible input. As far as output

is concerned, Long (1990: 32) argues that PPP sets a premium on the

“immediate production of native-like target constructions”. This

connects interestingly with Willis D’.s (1996: 44) claim that it is

“conformity” rather than accuracy that PPP fosters. Even otherwise

redeeming features such as clear sequencing of activities or clarity of

lesson goals (Skehan 1998:94) are attacked on the grounds that

structure cannot be acquired separately, in linear, additive fashion. In

other words, learning is perhaps best seen as “an organic process”

(Nunan 1989: 149) which is hidden and not amenable to teacher

control (Skehan 1996: 18).

The logical and empirical grounds for the above claims are based on a

number of studies, going back to Corder (1967, cited by Willis J. 1996a:

46) and continuing to this day3. But for present purposes I will very

briefly describe Krashen’s Monitor Model and the Morpheme Studies

carried out in the early 70s (Krashen 1982; Dulay and Burt 1973,

described in Larson-Freeman and Long 1991 and elsewhere).

Krashen’s model differentiated between learning and acquisition and

argued that spontaneous speech was a result of the latter rather than

the former. In articulating a position which claimed that

comprehensible input coupled with i+1 and a low affective filter would

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 4

suffice for successful acquisition, he sent a clear message to language

teachers world-wide: formal instruction does not work. His theory was

largely based on the results of the so-called morpheme studies done in

the early seventies, in which Dulay and Burt found that there was a

common acquisition order for a subset of English morphemes that L2

learners pass through largely irrespective of L1 or formal instruction.

The stage was set for the first TBL revolution, as it were.

B Task Based Learning – early and mid 1980s.

Early attempts to introduce TBL were motivated not only by the

theories associated with the aforementioned scholars, but also by

Prabhu’s Communicational Language Learning Project (Willis J. 1996a:

52), regarded by many as “an exceptionally important project” (Beretta

1990: 321). Prabhu’s Bangalore Project, which ran from 1979 to 1984

in India, claimed that it was possible to acquire grammatical

competence without any sort of form-focused instruction (Ellis 1997:

47), but rather through “the creation of conditions in which learners

engage in an effort to cope with communication” (Prabhu 1987: 1).

Although Prabhu acknowledged the insufficiency of comprehensible

input alone (Long and Crookes 1992: 35), his claims were similar to

Krashen’s in many respects: he recognised that the acquisition of a

linguistic structure was not an instant procedure and that

interlanguage would develop when attention was focused on meaning

and task-completion. Luiz Otavio Barros.

Recent studies seem to lend only partial support to Prabhu’s success

(Beretta and Davies 1985, cited by Ellis 1997: 53). The general

consensus is that students’ performance in grammatical tests was

largely unsatisfactory and that there were visible signs of fossilisation

amongst learners.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 5

Because the project was so influential, the mixed results it yielded

clearly raised a note of caution to proponents of more orthodox modes

of task-based learning. That was, in turn, corroborated by an increasing

body of evidence which maintained that by and large form-focused

instruction does seem to work. This is what the next section is

concerned with.

C A Sigh of Relief

In recent years there have been a plethora of studies attempting to

investigate the effects of form-focused instruction on second language

acquisition4. These studies seem to differ in relation to the

wholeheartedness with which they advocate the need for grammar, but

the general conclusion is that formal instruction does seem to work,

particularly in terms of rate of learning and ultimate level of

achievement. Language teachers world-wide can sigh in relief: years

and years of grammar instruction have perhaps been more than mere

waste of time after all:

(F)ormal SL instruction does not seem to alter acquisition

sequences… On the other hand, instruction has what are

possibly positive effects on SLA processes, clearly positive

effects on the rate at which learners acquire the language, and

probably beneficial effects on their ultimate level of attainment.

(Larsen-Freeman and Long 1991: 321)

Clearly, any model of Task Based Learning viable for the 90s should

take those findings into account. In that respect, Willis J.’s (1996b: 11)

diagram is an excellent example of what instruction should consist of if

it is to be compatible with what has recently been discovered about how

people acquire second languages5:

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 6

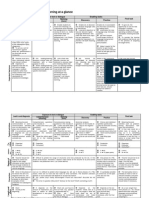

CONDITIONS FOR LANGUAGE LEARNING

ESSENTIAL DESIRABLE

EXPOSU MOTIVATIO USE INSTRUCTION

RE N

Adapted from

Willis J. (1996b:11)

The way in which modern language pedagogy has been trying to deal

with the “essential / desirable equation” is the prime concern of part 2.

By surveying the literature and drawing on my own professional

experience, I will tacitly imply that there might be a link between the

current state of affairs in TBL pedagogy and the negative teacher

perception I referred to earlier in this paper.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 7

PART 2

D Fuzzy Edges

Since it is commonplace practice in the literature to regard task as the

basic point of organisation in TBL (Long and Crookes1992: 41; Estaire

and Zanon1994: 13), it is perhaps worth spending a few moments

examining current definitions of the word task as it is used in language

teaching.

Different writers tend to assign somewhat indiscriminate meanings to

the word task, many of which seem to share a lack of pedagogic

usefulness:

Any structured language learning endeavour which has a

particular objective, appropriate content, a specified working

procedure and a range of outcome for those who undertake the

task. (Breen 1987: 23, cited by Long and Crookes 1992: 110)

A piece of work or an activity, usually with a specified

objective, undertaken as a part of an educational course or at

work. (Crookes 1986: 44, cited by Long and Crookes1992: 111)

An activity which require[s] learners to arrive at an outcome

from given information through some process of thought and

which allow[s] teachers to control and regulate that process.

(Prabuh 1987: 24)

Experience has shown me that when faced with such vague definitions,

teachers often have considerable difficulty in deciding whether any

given activity merits the label task. Fortunately, however, there are

more useful descriptions such as the one proposed by Skehan:

A task is an activity in which: meaning is primary, there’s

some sort of communication problem to solve, there’s some

sort of comparable real world activities, task completion has

some priority and the assessment of the task is in terms of

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 8

outcome. (1998: 95)

This and other definitions geared more specifically towards the

instructional roles of tasks (such as Nunan 1989: 10) emphasise the

pivotal role of meaning, which is usefully illustrated in the diagram on

page 6. However, that diagram also shows that a focus on form should

run parallel to meaning and use. In other words, it seems important to

attempt to “focus on form while learners are concerned with message

conveyance” (Ellis 1997: 82). Skehan portrays this somewhat paradoxical

issue rather eloquently:

Avoidance of specific structures and engagement in worthwhile

meanings are matters of degree rather than being categorical.

(1998: 96)

(Interestingly, teachers often responded to such a statement with empty

gazes and puzzled faces.)

At any rate, in order to address the aforementioned “meaning-form

equation”, TBL pedagogy has, amongst other things, created a plethora

of labels to be attached to different categories of tasks. The next section

describes these labels.

E Fuzzy Edges – part 2

When examining the literature, one finds several sub categories of tasks,

classified according to the sorts of learning goals each one tries to

achieve. Nunan (1989: 40), for example, differentiates between pedagogic

and real-world tasks. He claims the former “are unlikely to be performed

outside the classroom but stimulate internal processes of acquisition”,

while the latter attempt to “approximate in class the sorts of behaviours

required in the real world.” Long (1990: 31-50) proposes a similar

division: pedagogic tasks and target (or real-world) tasks. He points out

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 9

that pedagogic tasks “provide a vehicle for the presentation of

appropriate target language samples to learners.” On a similar tack,

Estaire and Zanon (1994:15) coined the term enabling tasks to refer to

those activities which provide students “with the necessary linguistic

tools to carry out a communication task” which in turn often leads to a

final task. Luiz Otavio Barros.

It should come as no surprise that teachers are often misled into

drawing somewhat misconceived -though not always easily refutable-

parallels with PPP: “Oh I see. So the enabling tasks would be the practice

phase and the final task the production.” Or “So pedagogic tasks are a

sort of presentation.” To say nothing of RSA/UCLES Certificate lesson

plans in which purely form-focused activities (in the “fill in the gaps with

ing or infinitive” moulds) tend to be consistently mislabelled as “enabling

tasks.” I usually attempt to clarify concepts by arguing for example, that

for an activity to qualify as an enabling (or pedagogic) task, it must be a

task in the first place. That has seldom proved helpful, however, since as

I have argued, it is often difficult to draw a line between “task” and “non-

task”.

Labels and jargon notwithstanding, the key issue which advocates of TBL

and most importantly – classroom teachers – have to contend with is the

degree to which production tasks should be related to specific language

structures. There seem to be two opposing views. While some would

claim that tasks should be designed and carried out without any sort of

linguistic agenda, (Willis J. 1996b and elsewhere), others seem to be in

favour of task design that in one way or another attempts to “trap” target

language structures (Ellis 1997; Loschky and Bley-Vroman 1993). I will

now examine each model in turn.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 10

F The Willis’ Way

Willis J.’s (1996b) basic assumption seems to be that transacting

communicative tasks will drive forward language acquisition. She takes a

firm stand in that respect and claims that while doing tasks learners

should be free to use “whatever language forms they want” (1996b: 44),

which appears to be consistent with the basic tenets of TBL (see page 9)

and ultimately with Willis D.’s views on “conformity”. To substantiate her

claim, she draws on an experiment (Willis and Willis 1988, cited by

Skehan 1998: 123) in which a task designed to elicit sentences like “If I

were you, I’d…” was given to a group of native speakers. She found that

the target structure was seldom used.

It will be recalled from the chart on page 6 that Willis J. does not dismiss

the importance of form-focused instruction. She recognises the potential

dangers of gaining fluency at the expense of accuracy (1996a: 55) -

which seemed to be, incidentally, a major flaw of the Bangalore Project.

Based on this notion and on Labov’s idea that accuracy and complexity

of language depend on whether discourse is private or public / planned

or spontaneous (1972 cited by Willis J. 1996a: 55), she created the

following framework for task- based instruction:

Exposure PRE-TASK

Introduction to topic

and task

TASK CYCLE

Use and exposure Task

Focus on form Planning Feedback

Use and exposure Report Feedback

Exposure and focus LANGUAGE FOCUS Feedback

on form Analysis and Practice

(Adapted from Willis J 1996b:38 )

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 11

Interestingly, Willis J. chooses not use the labels such as “target task” or

“enabling task” (discussed in section E), which arguably makes it

difficult for teachers to relate her framework to current terminology. At

any rate, for the purpose of this paper I am going to focus on how each

phase claims to promote accuracy and what sorts of practical problems

might arise.

The planning phase seems to suggest that accuracy will develop as

students plan what they are going to say during the report phase, with

the teacher “advising students on language, suggesting phrases and

helping students to polish and correct their language.” (1996a: 56)

Therefore the report phase should ideally be performed more accurately,

not only because of the planning that took place but also because of the

nature of public performance.

However, most of the teachers I have trained seemed to be somewhat

sceptical of Willis J.’s framework. There was a widespread perception

that it fails to take into account a number of context-specific variables

and wrongly assumes that: 1) Both adults and adolescents will be always

interested in the topic proposed and therefore will be willing to polish

and repolish countless times whatever it is that they said during the

task; 2) Students’ will profit linguistically from systematically listening

to their peers’ reports6 3) all classrooms across the globe have few

students, with whom the sort of close monitoring suggested by the model

can be managed. In other words, Willis J.’s (1996b: 34) claim that “the

only safe way is to listen to them planning and doing the tasks and find

out what meanings they want to convey” is certainly not applicable

across a wide range of teaching situations, especially as far as class size

is concerned.

As for the language focus phase, reassuring though it is generally

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 12

considered to be, quite a few teachers tend to find the “accuracy after

task” approach in many ways similar to familiar deep-end techniques

and therefore “something they’ve been doing for years”. Similarly, they

usually find it hard to draw a line between “PPP-like” and “TBL-

compatible” language-focused activities. For example, under which

category might one place activities such as the ones proposed by Ur

1988?

From a teacher’s perspective, I tend to agree that most of these claims do

actually hold up to a large extent. From a trainer’s standpoint, I believe

that there is also another reason for concern, namely the role of exposure

in Willis J.’s model. The framework shows that students will be exposed

to relevant language all the way through, by listening to the teacher,

peers and native speakers doing the task (on tape) (Willis J.1996b: 34) –

in other words, students are provided with plenty of input throughout.

Recent studies, however, have shown that learners generally process

input for meaning before they process it for form (Van Patten 1996,

discussed by Skehan 1998:46). It has been found that only input that is

“enhanced” (Sharwood Smith 1993 cited by Ellis 1997: 152) is likely to

be consciously “noticed” and become available for intake, effective

processing and interlanguage development. It seems to me that by

adopting a somewhat “Krashenian” view on input processing, Willis J.’s

model fails to provide students with the sort of “engineered” exposure

described above.

G Trapping Structures

Noticing, input enhancement, real-world, pedagogic, communicative,

enabling, form-focused, meaning-focused, pre, final…

TBL terminology is a delight for the Applied Linguist - and arguably a

nightmare for the average ELT practitioner. This section adds another

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 13

five items to the jargon-laden Task-Based terminology: “focus on form”

vs. “focus on forms” (Long and Crookes 1993: 27-56); “feature-focused

tasks” vs. “focused-communication tasks” (Ellis 1997: 82) and “structure-

based communication tasks” (Loschky and Bley-Vroman 1993: 123-167).

All these task types, as we will see, revolve around one basic notion: the

extent to which tasks can “trap” grammar structures, thereby promoting

“noticing” and interlanguage development.

Focus on form refers to part-practice of isolated linguistic features and is

what Ellis refers to as “feature-focused” teaching. In the moulds of PPP,

as it were. Focus on Forms, on the other hand, is what focused-

communication tasks propose, i.e., “an attempt to direct learner’s

attention to specific grammatical properties during the course of

meaning-based activities” (Ellis 1997: 82).

Focused-communication tasks are in many ways remarkably similar to

structure-based communication tasks, as Ellis himself suggests (1997: 82).

They can fall into three distinct categories, depending on how prominent

the use of a linguistic form is made: task naturalness, task utility and

task essentialness. (Loschky and Bley-Vroman 1993: 132). The first

group describes tasks that make the use of a specific structure “natural”,

but that can be performed successfully without it. This is perhaps

closest to the type of task Willis and Willis would advocate. Halfway

through the natural-contrived continuum, we can find the second group.

Tasks in which the use of a specific language point is useful, but not

essential, especially if we consider that in task-based learning successful

completion of a given task is usually measured in non-linguistic terms.

Proponents of task-naturalness (and to some extent task-usefulness) are

faced with what I see as two major problems. First, it could be

convincingly argued that the extent to which the use of a particular form

is natural in any given task is subject to empirical verification (Loschky

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 14

and Bley-Vroman 1993: 135). That is precisely what Willis and Willis’

experiment suggests. Moreover, Loschy and Bley-Vroman claim that

such tasks can not teach a new language structure (which most

language teachers would probably agree with), but automise a structure

that has already been acquired. But perhaps the most significant issue is

whether such atomisation will actually promote interlanguage stretch.

Recent studies have shown that when trying to cope with the pressure of

real time communication, learners tend to rely on lexicalised language

(Bygate 1988 cited by Skehan 1998: 68) amongst other achievement

strategies (see Skehan 1996: 17-30). This means that to get their

message across in real time, students may tend to resort, for example, to

the use of unanalysed formulaic language and paraphrasing, largely

bypassing syntax. In other words, learners often become “great task

achievers but poor language users”, as wittily described by some of the

teachers I have trained.

On those grounds, and according to Loschky and Bley-Vroman, the most

desirable criterion to attain is that of essentialness. In other words, tasks

in which the use of a certain structure is made essential for task

completion. Proponents of such tasks claim that they might be more

effective in promoting noticing and interlanguage change. However, this

model is not without its problems. For one thing, one could argue that it

simply is not possible to control what learners say:

The observations furthermore suggest that the possibility of

manipulating and controlling the students’ verbal behaviour in

the classroom is in fact quite limited. (Felix 1981: 109)

There is a further problem:

No doubt, such tasks are sometimes difficult to create; certainly

they will always be harder to create than tasks in which the

structure is merely natural or useful. (Loschky and Bley-

Vroman 1993: 147)

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 15

Experience has shown me that not every classroom teacher is necessarily

an expert in task design. And that is arguably what has been assumed

so far.

In an attempt to resolve the natural-essential dilemma, Ellis (1997: 150)

suggests that focused-communication tasks be geared to comprehension

rather than production. These tasks differ considerably from the ones

described so far in that learners are required to process the target

language, not to produce it.7 Ellis calls them “acquisition-compatible

grammar tasks” (Ellis 1997: 149).

A cursory look at the examples in the appendix reveals that even though

there is no risk of “conformity” in production (see page 4) or fossilisation

due to lack of “noticing”, there is still a relatively wide gap between the

sort of language processing that takes place during such tasks and the

real operating conditions under which unplanned language use is

thought to occur. Ellis’ model does not suggest ways in which this issue

can be addressed.

H Conclusion

As the reader will appreciate, this paper was an attempt to shed some

light on the following question:

“Since it is now generally agreed that the PPP approach is ill-founded,

what’s the best way to teach grammar for communication?”

I have attempted to show that there are at least three possible answers:

“ You shouldn’t have any sort of linguistic agenda. Expose learners to

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 16

the target language, and devise tasks focusing on meaning and use.

Then later on do some accuracy work based on the language students

used when trying to communicate.”

“ No, that way learners will fossilise. Try to devise communicative tasks

in such a way that students are likely to use a given structure. But be

careful! Keep students’ attention focused on meaning and use. They

shouldn’t feel they’re practising isolated bits of language.”

“ You can’t control what students say. It’s better to use tasks in which

learners are encouraged to think about the language, rather than

produce it.”

Drawing on my professional experience, I have tentatively argued that

none of these answers provides the average EFL practitioner with a

coherent and realistic set of principles and techniques for classroom

implementation. Unless that happens, it is my belief that the PPP

paradigm will continue to be the most widely used framework for

grammar teaching for many years to come.

(4287 words)

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 17

Notes

1 The idea for this title was based on Peter Medgye’s thought-provoking article “ Queries from

a Communicative Teacher”.

2 In this paper the terms framework, approach, model and paradigm will be used

interchangeably when referring to PPP.

3 See Larsen-Freeman &Long (1991:81-113) for a comprehensive survey.

4 See Ellis 1997 (56-75).

5 Though one might wish to claim that these findings are debatable. For example, see Larson-

Freeman and Long 1991: 322.

6 Refer to Ellis 1997 for a discussion on how the classroom might not be the ideal setting for

grammar acquisition.

7 Please refer to the appendix.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 18

References

Bereta, A. 1990 “Implementation of the Bangalore Project”. In Applied Linguistics 11(4), pp. 321-

37.

Crookes,G. and Long, M.H. 1992 “Three Approaches to Task-Based Syllabus Design”, in Tesol

Quarterly 26(1), pp. 27-56.

Ellis, R. 1997 SLA Research and Language Teaching, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Estaire, S. and Zanon, J. 1994 Planning Classwork: A Task-Based Approach, London:

Heinemann.

Felix, S.W. 1981 “The Effect of Formal Instruction on Second Language Acquisition”. In

Language Learning 31(1) pp. 89-111.

Kumaravadivelu B. 1993 “The name of the Task and the Task of Naming: Methodological Aspects

of Task-based Pedagogy”. In Gass, S.M. and Crookes G.(eds). Tasks in a Pedagogical Context,

(pp 69-96), London: Multilingual Matters.

Larsen-Freeman, D. and Long, M.H. 1991 An Introduction to Second Language Acquisition

Research, London: Longman.

Lewis, M. 1993 The Lexical Approach, London: LTP.

Long, M. 1990 “Task, Group and Task-group Interactions”. In Anivan, S.(ed) Language Teaching

Methodology for the 90s.(pps 31-50). Singapore: Seameo.

Loschky, L. and Bley-Vroman, R. 1993 “Grammar and Task-Based Methodology”. In Crookes,

G. and Gass, S.M. (eds). Tasks and Language Learning (pp.123-67). London, MultiLingual

Matters.

Nunan, D. 1989 Designing Tasks for the Communicative Classroom, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Medgyes, P. 1990 “Queries from a Communicative Teacher”. In Bolitho, R. and Ronner,R. (eds)

Currents of Change in English Language Teaching, (103-109), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prabhu, N.S. 1987 Second Language Pedagogy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skehan, P. 1996 “SLA Research and Task-Based Instruction” In Willis, J. and Willis, D.(eds)

Challenge and Change in English Language Teaching (pp. 17-30). London: Heinemann.

Skehan, P. 1997 A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Willis, D. 1996 “Accuracy, Fluency and Conformity”. In Willis, J. and Willis, D.(eds) Challenge

and Change in English Language Teaching (pp. 44-51). London: Heinemann.

Willis, J. 1996a “A Flexible Framework for Task-Based Learning”. In Willis, J. and Willis, D.(eds)

Challenge and Change in English Language Teaching (pp. 52-62). London: Heinemann.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 19

Willis, J. 1996b A Framework for Task-Based Learning, London: Longman.

Ur, P. 1989 Grammar Practice Activities. A Practical Guide for Teachers, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 20

Notes

1 The idea for this title was based on Peter Medgye’s thought-provoking article “ Queries from

a Communicative Teacher”.

2 In this paper the terms framework, approach, model and paradigm will be used

interchangeably when referring to PPP.

3 See Larsen-Freeman &Long (1991:81-113) for a comprehensive survey.

4 See Ellis 1997 (56-75).

5 Though one might wish to claim that these findings are debatable. For example, see Larson-

Freeman and Long 1991: 322.

6 Refer to Ellis 1997 for a discussion on how the classroom might not be the ideal setting for

grammar acquisition.

7 Please refer to the appendix.

© Luiz Otavio Barros 1999. All rights reserved. 21

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Luiz Otavio Barros - TimelinesDocument11 paginiLuiz Otavio Barros - TimelinesLuiz Otávio Barros, MAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Task-Based Learning at A GlanceDocument2 paginiTask-Based Learning at A GlanceLuiz Otávio Barros, MA100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Luiz Otavio Barros: Classroom Routines For Awareness and IndependenceDocument6 paginiLuiz Otavio Barros: Classroom Routines For Awareness and IndependenceLuiz Otávio Barros, MAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Luiz Otávio Barros: Observation Guidelines at Advanced LevelDocument2 paginiLuiz Otávio Barros: Observation Guidelines at Advanced LevelLuiz Otávio Barros, MAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Luiz Otavio Barros: PPP X Task-Based LearningDocument4 paginiLuiz Otavio Barros: PPP X Task-Based LearningLuiz Otávio Barros, MA100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Luiz Otávio Barros: Classroom ManagementDocument3 paginiLuiz Otávio Barros: Classroom ManagementLuiz Otávio Barros, MAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Stretching The Advanced Learners' EnglishDocument2 paginiStretching The Advanced Learners' EnglishLuiz Otávio Barros, MAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Luiz Otávio Barros: Teaching VocabularyDocument3 paginiLuiz Otávio Barros: Teaching VocabularyLuiz Otávio Barros, MAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Luiz Otávio Barros: Options in Grammar TeachingDocument5 paginiLuiz Otávio Barros: Options in Grammar TeachingLuiz Otávio Barros, MAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Luiz Otávio Barros - Critique of Prabhu's Task-Based LearningDocument20 paginiLuiz Otávio Barros - Critique of Prabhu's Task-Based LearningLuiz Otávio Barros, MA100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Luiz Otavio Barros: Teaching Spoken English at Advanced LevelDocument22 paginiLuiz Otavio Barros: Teaching Spoken English at Advanced LevelLuiz Otávio Barros, MA100% (1)

- Luiz Otavio Barros - Corpus Data X Textbook InfoDocument21 paginiLuiz Otavio Barros - Corpus Data X Textbook InfoLuiz Otávio Barros, MA100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Optimize Supply Network DesignDocument39 paginiOptimize Supply Network DesignThức NguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Sri Lanka, CBSLDocument24 paginiSri Lanka, CBSLVyasIRMAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- ZO 503 Physiological Chemistry by Dr.S.S.KunjwalDocument22 paginiZO 503 Physiological Chemistry by Dr.S.S.KunjwalAbhishek Singh ChandelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Filipino FamilyDocument11 paginiThe Filipino FamilyTiger Knee97% (37)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- On MCH and Maternal Health in BangladeshDocument46 paginiOn MCH and Maternal Health in BangladeshTanni ChowdhuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- Causes of The Renaissance: Silk RoadDocument6 paginiCauses of The Renaissance: Silk RoadCyryhl GutlayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Description of Classroom Management PlanDocument10 paginiDescription of Classroom Management Planapi-575843180Încă nu există evaluări

- GooglepreviewDocument69 paginiGooglepreviewtarunchatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salt Analysis-Ferric ChlorideDocument3 paginiSalt Analysis-Ferric ChlorideVandana0% (1)

- 1-2-Chemical Indicator of GeopolymerDocument4 pagini1-2-Chemical Indicator of GeopolymerYazmin Alejandra Holguin CardonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theories of Translation12345Document22 paginiTheories of Translation12345Ishrat FatimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Mafia Bride by CD Reiss (Reiss, CD)Document200 paginiMafia Bride by CD Reiss (Reiss, CD)Aurniaa InaraaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Latihan Soal Recount Text HotsDocument3 paginiLatihan Soal Recount Text HotsDevinta ArdyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land Equivalent Ratio, Growth, Yield and Yield Components Response of Mono-Cropped vs. Inter-Cropped Common Bean and Maize With and Without Compost ApplicationDocument10 paginiLand Equivalent Ratio, Growth, Yield and Yield Components Response of Mono-Cropped vs. Inter-Cropped Common Bean and Maize With and Without Compost ApplicationsardinetaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edtpa Lesson Plan 1Document3 paginiEdtpa Lesson Plan 1api-364684662Încă nu există evaluări

- KOREADocument124 paginiKOREAchilla himmudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sankalp Sanjeevani NEET: PhysicsDocument11 paginiSankalp Sanjeevani NEET: PhysicsKey RavenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Openstack Deployment Ops Guide PDFDocument197 paginiOpenstack Deployment Ops Guide PDFBinank PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRP Format MbaDocument6 paginiMRP Format Mbasankshep panchalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Chapter 12Document52 paginiChapter 12Mr SaemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Provisional List of Institutes1652433727Document27 paginiProvisional List of Institutes1652433727qwerty qwertyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cult of KUDocument31 paginiCult of KUEli GiudiceÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Comparison of Fuel Cell Testing Protocols PDFDocument7 paginiA Comparison of Fuel Cell Testing Protocols PDFDimitrios TsiplakidesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rise of NationalismDocument19 paginiRise of NationalismlolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Database Case Study Mountain View HospitalDocument6 paginiDatabase Case Study Mountain View HospitalNicole Tulagan57% (7)

- Ezequiel Reyes CV EngDocument1 paginăEzequiel Reyes CV Engezequiel.rdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bread Machine Sunbeam 5891Document44 paginiBread Machine Sunbeam 5891Tyler KirklandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analog To Digital Conversion (ADC)Document62 paginiAnalog To Digital Conversion (ADC)Asin PillaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Radiant Tube BurnersDocument18 paginiRadiant Tube BurnersRajeshÎncă nu există evaluări

- DEWA Electrical Installation Regulations Section 1 OverviewDocument123 paginiDEWA Electrical Installation Regulations Section 1 Overviewsiva_nagesh_280% (5)