Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Rowland - The Evolution of The Buddha Image

Încărcat de

VirgoMoreTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Rowland - The Evolution of The Buddha Image

Încărcat de

VirgoMoreDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

l fi 39

THE EVOLUTION OF

THE BUDDHA IMAGE

BENJAMTN ROWLAND JR

---

THE ASIA SOCIETY. INC.

DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS. INC.

. ., .._ L

\ ft. - .J I

' u 16. .:. , . 1 '- nt ,.

lJWITR,\ L \ nrR .\ IOLOOICl&l.

NEW DIKJD.

Aee. No

Date I

I'.&IJ No

\I..._ -

.-, .. , ............ -... -

, .. '1: ..... . . .... . . ... __

. . .

1

r: ,-. ..- r' rr,.. ..._

oiToo o o.'loooi I"M._,__.. - o

TilE l VOI U 110'-J Or IIIE BL.. DD I IA I1\I 1\Gl "u cautlvguc of an exhibition

,elected b) l'rore.sor !lenjamin Ro" land. Jr and ' hown in the O.tllcries of Asia

Hou>c '" nn acttvtt) of the A<iil to further grc;uer umlen.tnnding and

mutu<tl apprecinuon bet\\ccn the Lnitcll SUite' und the people, <>f A<iu.

\ n '"" llou>e Gall<l') Publicution all nghb rc.,.,ned.

Pnntcd 111 b) Crai\ I ncorr>ormcd 19(>3

Dl\tributed b) llarr) " \bram. Inc .. 'c" \ ork

'

1>-

'tA

,._J

\h.

""-

PREFACE

If 'r llrt (ortu11ott m hoi11g ohlllmtd tilt ltamrd serriru of Pro(tssor 8rnjamil1 Ro11/and

attht Wil/iam Hayu Fogg An \lustum ofllanard Lnitrsity i11 asstmbling tlu.r <'X-

hibitioll N01 Olll) has Professor Ro .. Jand hrillen tht complttt t<'W of this catnlollut.

11'/iir/1 ujfers liS o wliq11t ami s urrey cl) the theme, hut he has <1/so

illustrations to his tt.w a'i a_s the uork.f of art that pcrmu us to trme

of the Buddha through n serirs of da<umtiiiS. Tlte catalogue. as a hook.

and tM ,.,,hibition Itself hart bu11 designtd h) Richard Cleefand of tilt' Asia lloi.S<'

Gttlfery. .

IVt ll'ish to express our 11'/trllltst.grar/tm/e tu all of the lt11ders. hoth .fmtric'a/1 ami

"ho ptrmltied i1.1to borroh Jhtlr 011 this OC't'OSion Somt fl{

lenders hart o/ttll lte/ptJ/. .u/(1 Hotut in tills f{rnerous forltion and others 11011 rt'spo11d

w our first requests for loans. Among tM /mter ""particularly ish to tltr Or/en

ral \fuuw11 111 Rome, i7ii 'baitokuji 11useums.

Withom tltt kmd {Wtmissioll o{tht Japanese CommLuio11 for tltt Protution o{ Cu/-

11/ra/ Proptrties amltlrl> eu rt-ody assisto11rt of.\lr. ltro E11Ja}i. \ftlllogmg Director oj

tlrt Nfltoll Kei:m Sltimb1111 ( Jopo11 Eco11omi< Jotu11ol) . tire spec ill/ /QliiiS from Jopa11

multl110t hme ht>e11 ftussib/e. /11 tlrls COIIIIertloll ,..,. deep( CtJJprecilllt' the ltelp gi''''" 11s

in Japo11 b)' \fr. Jolm Rosell}itld, Research Ft-IIOh of llofl'nrd ('llhwslt)' OIIti

Pro(nsor Ro11/and's m Tokyo,

'

As a cull image and an anistic ideal the Bud-

dha image is for the entire Eastern world the

equivalent of the rcrresentation of Christ, first

invented in early Christian times and brought to

perfection b) the great master;, of the medie,al

period and the Renaissance. This single iconic

fo m. which may be understood to include por-

trayals of the mortal Buddha. Sakyamuni or

Gautama. as well as the di,ine Buddhas of the

Mahayana pantheon, presents o concentrated

focal point for the ;tudy of the development of

a single ae;,thetic ideal in rehgious an. The

changes that the type underwent O\Cr a penod of

many centuries illustrate throughout this long

history the de,elopment of religious and nation-

al ideals in all the realms of the Orient. In this

one invention of religious anists we can see un-

fold the whole history of Eastern an.

According to a legend reported in many

different sources. the very lim image of Buddha

was a sandalwood statue carved in the Master's

lifetime for King Udayana of Kau.sambi. The

story relates that .. When Tathagata lirst arrived

at complete Enlightenment. he ascended into

Heaven to preach the Law for the benefit of his

mother. and for three months remained absent.

King Udaynna. thinling of him \\ith affection.

desired to have an image of hi s person: there-

fore, he asked Mudgal)'ayanaputra by a spiri-

INTRODUCTION

tual po\\er to transpon an artist to the heavenly

mansion> to obsel'\e the e\ccllem marks of the

Buddha's body and cnrve a sandalwood >tatue.

When Tnthagata returned from the heavenly

palace. the cal'\ed figure of .andah' ood arose

and saluted the Lord of the World. The Lord

then graciously addressed it and said. 'The work

expected from you is to toil in the con,er;.ion of

unbelie,ers and 10 lead in the wa} of religion

future age.: One could hnvc no more eloquent

statement of the missionary function that was to

be performed by the tronslntion of the Buddha

image to the entire Asian \\Orld. HsUnn-tsang,

the famous Chinese pilgrim of the seventh

century. referring 10 the Udnyana Buddha. re-

lates that peoples of m3lly regions \\orshipped

copies of it and they pretend that the likeness is

a true original one and this is the original of all

such figures." We shall encounter reflections of

this famous sandal\' ood statue in many exam-

ples of Chinese and Japanese art. Probably the

Udayana legend is a pious fabrication which at

some ume before Hsiinn-tsang's 'i;,it was

nnached to the firM images of Buddha carved in

Gandhara as early as the first century A.D. The

legend of the Uda)ana statue b embroidered in

certain Tibetan te\t;, b) the additional informa-

tion that the Buddha. in order to facilitate 1he

task of the artist who wa> blinded by the

6

Tathng:un's effulgent brilliance. obligingly ca,t

hi' rctlection upon the surface of a pool. The

fact that the likeness was taken from a reflection

on \\3ter. these accounts .:I). e\plains the

"riprling" drapery in >tntue> of the so-<:alled

Uda)ana t} pe. lt is perhaps not too much to

;uppo>c that this pan of the story was in,ented

con.iderably later to explain the ripples of the

clnssicul garments of thc>e fir>t icons of

Snkyamuni.

lt is plain that, the beautiful Udnyana myth

notwith>tnnding. the fir>t representations of

Sakyamuni in human form \\Cre only crented

cent uric> after his death" hen a special need was

felt for ;.uch anthropomorphic reproentations

of the Teacher. In early Buddhism. "hich \\35 a

wa> of life or a philosophical system based on

the doctrine of the founder. there was no need

for representations of the Ma>ter. lt was be-

lieved that the Buddha "who h:ts gone beyond

the fetters of th<! body cannot be endowed by

art "ith the likeness of a body" or. as "e may

read in the Digha-nikaya. "On the dissolution of

the body bc)ond the end of his life neither gods

nor men shall knO\\ him ... The monal Teacher

had pa;.scd with his irvana mto a realm of

m'isibilit). and in early Buddhi>t art his pres-

ence m narratives of his earthly career was sym-

bolit.ed by such emblems ns the empty throne

for the Enlightenment. the wheel for the First

Preaching. and the stupn or relic mound for his

'irvana (Figure /). In the Kalingahodhi Jaraka

the Buddha states that he c:1n be properly shown

a bodhi tree.

With the passing of the centurie5 Buddhism

wa; tmn;formed from a r:uher hmited and

selfish religious system. in \\hich the way to

salvation was open only to those who could

renounce the world for n monastic existence. to

n religiou alTering the promise of salvation to all

men who foUowed the eight-fold path. Gradu-

ally the demand arose for the reassurances and

comfort of devotion to the per>On and founder

him>elf rather than his doctrine. The cult of

relics fo>tered by the Emperor Asoka in the

third century B. C. is an early of this

gro" 1ng "orship of the Buddha himself. Puja or

prayer to Sakyamuni himself replaces yajna or

the contemplation and practice of his message.

This process of change was abetted by the

gro\\ th of the blwkri cult, which means essen-

tiall) the passionate love of the devotee (bhakra)

for a particulnr di,inity. This was a de,elop-

ment from a S)Stem of thought to a popular

religion. Sahation became possible through the

devotion of the worshipper to his god as a reac-

tion against the tedious intellectualism of the

Upunislwds or the hard road to salvation offered

by the early Buddhist creed. The development

was affected. too, by the cult of the Hindu god

Kri>hna who said. "None who is devoted to me

is lo>t." Blwk1i. "the less troublesome way,''

itself to the manifestation of the deity

that 1s most accessible and most at hand.

Blwlw 1mplies the of the Buddha,

ju>t n; this auachment to a personal god implies

the deification of the Buddha, and idolatry. 1t is

also probable that the steps leading to the first

Buddha image included the influence of the

anthropomorphic tradition of the Hellenic

world "hich since the conque>t of Alexander

had been in close contact with India.

The worship of divinities in anthropomorphic

form had existed in the cult or nature spirits as

early a> the Indus Valley period. Such divinities

as .l'llkshis and a proto-Siva nrc commonly found

on the Indus Valley seals. In the Maurya period

the )'llk.1his arc portrayed ns superhuman titans,

FIG. 2. COIN Of KANISHKA.

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

FIG. 1. REliC MOUND SYMBOLIZING THE NIRVANA

FREER GALlERY OF ART.

7

8

and the rcprnenl(!lion of these and other old

Ora' 1dian >Pirit> .uch as the naga;, common in

;ome of the great monuments of the early

Cla>>ic period. in which the Buddha is portrayed

onl) in aniconie form.

In the beginning. at least. the image

in India was only ;I ;ubstitute for the prototype.

lh function may be explained by the 1\0rd> of

the Hermeneia of Athos regarding Christian

ICOn<: .. All honor that 1\C pay the image 1\C refer

to the pe: namely him who$e image it

b. Ami iu no wise honor we the col or or th: nrt.

but the archetype in Christ who i; in Heaven."

A> in the history of all rehgJOns it wa> only later

that a fetishi>tic 1\0r>hip came to be pa1d to the

icon;; rather than their pro tot} pc>.

The amhropomorph1c representation of the

Buddha almost certnmly went hand 1n hand

"1th n change in the religion frnmthe ll inn).ln:l

to the Mahayana doctrine. In .uch sutra> as the

Mahtll'fiS/11 and the Saddltarma Pwularika.

1\hlch must date from the Kushan period of the

firM and SCC011J centorics A.D .. the Buddh:t is

nhetd) described a> a superhuman per.onage.

no longer a mortal teacher. but a god

and eternal as Orohmn himself.

' In Hinayan:1 Buddhism. salvation was po>

''ble through the ex unction ofauachm.:nttl.l the

b) p1acticmg the and meditation

prncribed b) Sakyamuni. The repre>entallons

of in Hinayana Buddhi>m 1\Cre not

neccs;;.u ily portro)nh of Gautama "'a dh mit)

but reminders of the Mus1er"s earthly tcuching

exemplified in his image. At the same time. they

offered the of devotion to his person.

Cenamly it "a;, hoped that . .omcho" from

be)ond the gate;, of 1nana. the departed

tcncheJ might anwer pr-.1yers and be\10" boons

a> LorJ Krishna re\\arded devotee>. Such na

atlltudc of de,otion to Sakyamum inevitably led

to hb .:onception as a god. stemming as it d1d

from the ancient Indian nttac.hment to personal

divin111e;,.

In Muhnyana Sakyamum the

mortul teacher is regarded ns the earthly ex

pr.:s;ion or appearance of a might) spiritual

bcmg. One of the fundamental tenet> of the

Great Vehicle is the concept of the Three

or Tril.mu: the Dlwmwkm11 the Buddhist

logo.,. an in>isible force permeating the uni,er>e

as the spiritual essence of' the ultimate and abso-

lute Buddha: the Sambltogak(t)'ll or Body of

Bhss 1s that tran;,figured Body of Sl>lendor

which the eterual Buddha reveals only to the

Bodhi>au,a;,: and the .Virmanakaya is the

noumenal earthly >hapc in which the co!>mic

Buddha re,ealed himself an illusion for the

benefit of mortals. lt is obvtously impossible to

H.inayana from Mahayana images

except by context or special :ntributes. We must

remember. too. that, in the iconography of the

Grcnt Vehicle. the cosm1c Buddha Va1rocana

and regents. the Dh)am Buddhas, governing

the four of the assume the

auitudcs und muclms of particular actions in

life of the mortal Buddha symbolized by these

same poses and gestures.

The I) pical Buddha image. beginning with the

>ery cnrlie;,t representation> 111 Gandhara and

shows the master "caring the

tic garment or stmg/wti, sometimes co,cring

both shoulder> or with the right shoulder burc.

As will be seen in specific examples later. the

head and body and limb' are characteli?.ed by

laJ. \ltonar or magic that distin

the anatom) of a Buddha from that or

ordinary monals. In both Mandmg and seated

image' the position of the hands or mudra ind1-

cates a certain power or function of the Buddha

or the gesture rnay bo associated "ith a parti-

cular event in his life. The most common of

these gestures is the ablwy11 mutlra. a gesture of

reassurance or blessing, not connected with any

specific event in the Buddha's life, in which the

roght hand is raised. palm outward. Other fami-

liar mwlras are the Dhpmlmudm or gesture of

meditation with the bands folded in the lap and

the hlmmispar.m mudra with the right hand of

the seated Buddha reachi ng down to touch the

earth. Both of these arc associated with the

Great Enlightenment and later arc adopted for

images of the Dhyani Buddhas Amitabha and

Akshobhya. TI1ere are essentially only two types

of Buddha image: the standing figure or the

seated Buddha. In the lancr the legs arc folded

as an invariable convention in the yoga posture.

even though the position of the hands may not

have anything to do with the act of meditat ion.

The representation of certain individual

/okshanos is extremely interesting for the

changes in form and iconography in

chapters in the evolution of the Buddha image.

One of more distinctive of these marks is the

uslmisha. the lump at the summit of the Bud-

dha' s head which. as a kind of auxilinry brain

ac.:ording to the accommodated that cos-

mic consciousness or supreme wisdom which

Sakyamuni auai ned at his Enlightenment. In

Gandhara sculpture this feat ure. perhaps be-

cause is was incomprehensible or distasteful to

artist> trained in the Graeco-Roman tradition.

was disguised by wavy locks or by a topknot

like that worn by Apollo in Hellenic sculpture.

In the purely l ndinn schools, the uslmisha is

frankly portrayed us a cranial protuberance

usually witb snail-shell curls. A11 ultimate devel-

opment in late Thai sculpture places a flame-

shaped fi nial at the top of the Buddha"s head,

perhaps as a symbol of the divine radiance

emanating from this magic center.

The halo or nimbus which comes to be an

inevitable a ttribute for al l Buddhist divinities

probably derives from the ancient Iranian con-

vention of symboliLing the celestial light of

t\hura Mazda by a disc or sun. sometimes. as in

the reliefs of Per,epolb. placed behind amhro

pomorphic representations of the Mazdaean

personification of light. From this so\J rce the

disc or halo found its way into early Christian

and BuddJt ist art as a means of signifying the

divine mdiance or ft'}as emanating from the per-

son of Christ and Buddha.

lt is generally believed that the earliest images

of the were mnde in the ancient prov-

ince of Gandhara toward the close of the first

century A.D. This region. comprising tbe pres-

ent northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan. was

then under the rule of Kusban Scythian kings, a

race of eastern Central Astan origin. who were

in close commercial nnd diplomatic contact with

the West. The craftsmen who served the KushaJt

religiou;, establishments were in the begi nning

Roman journeymen craftsmen From such east-

ern Mediterranean si tes as Alexandria and

Antioch. i\mong the li-st portrayals of Buddha

in human form is a likenes> on a gold coin of the

Emperor Kanishka. inscribed in provincial

Greek, BOO DO ( Figure 2) . Kanishb is known

as one of the great patrons of Buddhism who is

temembered for convening the second gc:ll

Buddhist council. His reign is belicwd to have

begun in 78 or 128 A. D. The presence of this

likeness or the Bud cl ha on the money of Kunish-

kn would seem to connote the previous

of statues of similar type.

The earliest Gandhnra Buddhas were u com-

9

10

bi111tlion of various elemcnl> druwn from 1he

pnnn repertory of the foreil!ll cruflsmen who

were Cllllcd upon to in,cnl on icon of the Bud-

dha. The head i> an adaptauon of the mdianl

)Outhful face of >uch a clasMcul pro1o1ype as the

Apollo Behedcrc. and the mantle 11 tlh its 'olu-

minou, fold' i> a Roman toga or pallium. 11 has

been 'Ui!!!C>Ied that the choacc of the Apollo

type :1> :a model for the features of Buddha had

a ccrwm iconographical approprin1cncS> 10 sig-

nlf'y that the Buddha. too, 11:t\ a Jler>Onification

of incll'ablc light. In the IV:tY the pallium

could be thought of as a suuablc garment for

the Buddha. since it had been a>sociated "ith

the great teachers and lhc prie>l> 11ho \\elcomed

the ;oul for the other world in the ffi)>tCI) cults

m the pagan West. The >lyle of the earliest

Gandhara Buddhas appro,imate' late Hellcnis

tic or Roman Imperial art of the early centuries

of the Christian era. As Indian carvers took

over the work of the firstgcncrotion of Roman

sculptor\, the Gandhara Buddhas gradually

undcn\ent a process of I ndianization. The

tmagc> become more ri@Jdl) frontal. and the

drapery. :b in the Roman pro,incial art of

Palm)rn. i reduced to a ;chematic pauem of

Mringhke loop> appliqu&:d 10 I he ;,urfact of the

body: at the same time the face assumes the

more hicroaic mask-like character ,,r an.

11 wa\ this ILliCSt type of Gam.lhara Buddha

which provided ahe model for countless repeti-

aions of the style in Central A;ia and the Far

Ea't.

Ju;t as 1hc relief of Gnndhara is

de\(lled entire!) to >ubjccb enhcr from the

Jowkaf or M:ene. from the life of the mortal

Buddha, 11 appears that pracltcally all of 1he

Buddha image> of lhb are rcpre>enta-

tion> of Snkyamuni. During the flr.t few ccn-

turic; of its existence. the region of Gandhara

and the nrt it produced seem 10 have been

dedicated to the expression of the ideals of

Htna)nn:l Buddhism. Only rorcl) doe> 11 seem

passable 10 rccogntzc port m} ab of the m) thical

Buddh:b of the \1ahayana pantheon. One cer-

tain mdication of the gradual predominance of

the Great \'ehicle i> the appearance of the colos-

>nl image. The most notable examples of the

Mahnynna concept of the Buddha ns a trons-

ccndcnt personage. the equivnlent of the ancient

Mahnpurusa or cosmic man. arc the colossal

image, of the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan.

The smaller 125-foot Buddha is an enlargement

of a relati,el) earl) Gandhara l)pe. and ahe 175-

foot Buddha (Figure 3) "ath ttS drape!) actually

allhed 10 the body on a net of strings co,ered

with clay is a magnification of the final lndian-

ized I) pe of Buddha image. The;c statues.

which were the wonder of the Chinese pilgrims

who visited the holy land of Buddhism from the

l'ourth century onward. provided the models for

the giant statues of the di' imzcd Buddha in

China and Japan.

Probabl) at a he same momentthattheentirely

foreign I) pe of Buddhist icon was created in

Gandhara, the workshops at Mathura, the

southern capital of the Ku;hans. produced an

Indian Buddha image. These of which

the one dedicated by Friar Baln at Sarnath is the

most famous. arc usually over-life-si:tc figures.

recalling the massive of the J'tli..fhi

\tatue> of the Maul) a and Sungu Period>. From

proiOI)peS they derhcd the l)pcal Indian

fcehng for expanshe \olume and the connOLa

taon of the softness and "armth of the flesh by

the ;\\citing roundnes> of simple interlocking

For reasons that are not entirely dear.

these Ku,han statues usually represent Sakya-

fiG. 3. COlOSSAl BUDDHA.

IAMtYAN, AfGHANISTAN.

'

'""'

-.:

_,

.. .......

~

..

~ r

..

...

..

~

..

..

.

~

...,._,

' .-

.

' .

.].,. ...

'

._, ,.

.......

~ '

..

,,

'

...,.

"'

.

-

--

-..

.,

ooc\

~ ,

'

.

~

\

( .

. -...

~ '

. ,

J

12

mun1 a Bodhisnnm: that is, wearing not the

mona>1ic mantle but a skirt or dhoti. and nude

from the \\aist up sa\e for the robe O\er the left

;,houlder. In contrast to the cold expres;ionle>;

of the Gandharn statues. the fucc, of the

Mat hum Buddhas arc shown with open eyes and

softly lips, so that they have a kind of

radiance and friendly warmth that welcome the

devotee'> adoration. Just as the Gandhara

sculpture rchcd on classical protol) pe>. the

Mathura cnr.crs created their \cr,ion of the

Buddha 1mage on the foundation of type> and

tcchmque' of the early Indian tradition.

tmagc, "ere made in accordance wtth

a li\ed >)'tcm of proportions and \\ith >etupu

lou' aucntion to representing the magtc marks

or lakfiltllltl\ that distinguished the body of a

Buddh:t from ordinary mortals. Folio" ing the

technique of the ancient Indian schools. the

drtt i)Cry i> mdicatcd only by incised line; "ith

u conceptual cmphu'i' on the seam> and border>

of the gum1cnt. There ''ere occu;ional unita

ton; of the Gandharn type in Muttrn. butthe;c

tra\C>tiC> of the provincial Roman ;,t) le are

V:htl> outnumbered b) the cult of com

plctcl) lndtan l)pc The Ku;.han Buddha\ of

1\lathura ,till remm something of the dtrcct

;.tatemcnl and po"er C\prCCd the ;.heer

bulk and ..ea le of the Maurya and Sunga 'latuc,.

Such charactcri,tb of the;e image> a' the

cnormou' breadth of ;.houldcrs and tin) \\al>l>

indicate lhe emergence of a formula for por

trU) ing the anatom) of a superman that wa' to

dewlofl intO U ;.ophi;ticated language or CX(WC>

'ion in the Gupta period.

A nwdilkation of the Kushan Buddha tyre

wa' ildOfllCd in the Andhm l.ingdom or

Amara-.tll and l\:ag<1rjunakunda in the e:lfl)

ccnturic' ol our era. These imagcs. 'duch arc

caned from a beautiful grccmsh\1 hite lime

are characterized by a rather \lilT hiemtic

quality; the bodies ha\e of the full

ne>s of the Mathura type. whi le the drapery.

usuall y represented in a series of li nes or ridges.

appears to be a convcntionulitation of the

Gandhara formula. The pla>tic au>tcrity and

sophistication of these images a I read) anticipate

the idea of the Gupta period. Close contacts

bet\\een the Andhra Empire and Ccylon led to

the introduction of thi> SI) le to Anuradham-

pura. perhaps as earl) as the fourth or fifth

centur) A.D. Image, of the Amara,au type.

both in stone and in bronLe. have been found in

lndo-China. Borneo. and the Celebe,. indieat

ing the enormous inlluence of the Buddhist

ci\ ili7.ation of South India.

The Gupta period. often a\ the

Golden Age of Indian art. i> not so much a

Renaissance in 1hc European sense of the term

ns it i' a culmination and refinement of many

earlier forms and of Indian art. The

cuhi\'atcd beauty of exprc,;,ion in poetry.

drama. and the dance ha'> 11; parallel m the

pl:t>tic arts. 11 is quite po"tblc to \U) "ithout

re'-Cr.ation that the Buddha tmage> of the

Gupta period repre.em the final \lCp m the

eolution of the Indian ideal of the cult image.

11 I> belie,ed th:ll the fourth or

fifth century the of Indian art "ere al-

ready formulated in such \\Ork; a; the K1111W

\11/rtl and the l'i.llmwlflflflll<ltwrum. These

\ll.\lrlrr e>tablished the norm' for ac>thctic pmc

ticc'> in much the .amc way U> the manuals or

the Byzantine tradi tion perpetuated the rule>

for nrti\lic procedures. ProportiOn\, mca;ure-

mcnh, posture>. ge;ture>. rnooth. and e\pres

'10n" fo1 different type' of images in p:unting

and -.culpture are all defined. Thc'e -.amc princi

., -

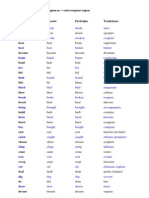

FIG. . CANON OF PROPORTIONS FOR

FIGURE OF THE BUDDHA TIIET AN.

pies of artbtic procedure continued 10 ,hape the

of art in India long after the c\Unction

of Buddh1sm in the thirteenth centul)

Ccnam lhed canons for the of ..acr<-d

images made their appeamnl-.: in India at an

earl} pcr1od. The purpose of the <';mons fixed b)

iconomctry 11as to produce likcnc"e' of the

gods valid and correct for wor,hip. and any

dc\iation from the formula 11oulu rc,uh in an

icon unlit for devotion. Such pro1>0rtion' were

intended 10 produce a nature tr:lll,ccnding

humanit} and its ephemeral. imperfect beauty.

The ba,ic unit of 11a' the angula

or linger. \ometimes from the breadth of

the finger 10 render hi' 1dcntilkation

4

I

I

I

1!1

I

'

I

I

I

12

1

4f

-

4'

11ith the icon more complete. \ppro\lmatcly

twelve con\tltutcd a thalcm or palm and

this unit 11as repeated mnc 11mcs for the hc1ght

of the standing figure and lh c umcs for the

<.eated figure'> I Figurt ./). mathema1ical

of proport1on. \IIth no reference to the

anatomy of human beings. 11as till

arbitrary one designild to produce a supernat-

ural rather than a human proportion. This

mathematical ,)',ICill of IOC;It-UrCI11Cill \\'liS bused

in part. too. on the magical properties of ccrtttin

numbers. Its u\c j, cumpaablc to the tnvcntion

of a super-human ana con,tructetl on the

bl:.is of an nb,trac:t modulu>. for the of

Eg) pt and Greece of the :trchaic period. The

13

14

angulas determined the proportion of eve!)

section of the image. and the face was generally

divided into three equal parts of four angulas

each: from hairline to eyes, eyes to base of nose,

and nose to the tip of the chin.

During the Gupta period the principal

schools or workshops for Buddhist sculptUre

were Mathura and Sarnath. and the types estab-

lished at these ccnters continued to influence the

making of cult images into the Period of the

Hindu Dynasties.

In style the statues of the fourth and firth

centuries from Mathura, like the superb exam-

ple lent by the William Rock hill Nelson Gallery

of Art. are a combination of elements assimi

lated from the Kushan and Gandhara Buddha

types. The standing image has the massive and

heavy proportions of the Kushan Buddha; the

drapery has been reduced to a schematic con

vention of quilted ridges fa lling in repeated

loops down the median line of the body. so that

the form appears nude as seen through a net

work of cords. The bodies of these Buddhas

retain the same feeling of expansive vol ume

through the construction in simplified rounded

planes that at the same time connote in abstract

fashion the warmth and fullness of the fleshly

envelope. The head of a typical Gupta Buddha

from Mathura is conceived as a spheroidal

mask with its smooth interlocking planes even

more suggestive of u pure- geometric volume

than its Kushan prototypes. This fullness com

municates a feel ing of warmth and aliveness to

the facial mask. The features of these Gupta

icons are unmistakably represented according

to a metaphorical method. whereby the individ

ual parts of the face are not imitated from

counterparts in any human model but from

certain shapes in the world of nature. regarded

as more beautiful and finnl than anything to be

found in the accidental and never perfect beauty

of a mortal face. Accordingly the countenance

has the perfect oval of the egg: the eyes arc

shaped l.ikc lotus buds or lotus petals: the lips

huve the fullness of the mango. and the brows

the curve of Krishnas bow. In the heads of the

Gupta images the hair is invariably represented

in the form of snail-shell curls covering the head

like a cap. This convention of tightly wound

spirals for the short locks exactly follows the

textual description of the appearance of the

Buddha's hair after he had cut ofr his princely

ringlets at the time of the Great Renunciation.

In a similar way the l t ~ k s l w n t l s likening the

Buddha"s Herculean shoulders to the head of

an elephant and his torso to the tapered body of

a lion are literally followed in the carving or

painting of a supernatural rather than a human

anatomy.

Among the great masterpieces of Gupta

sculpture are the Buddha images of Sarnath.

the sacred site near Benares that witnessed the

Buddha"s First Preaching. These statues are

fashioned of the same chunar sandstone that

more than five centuries earlier had been used

for the Asokan piJ iars. The Sarnath Buddha

type differs specificaUy from the Mathura ideal,

in that all traces of drapery folds have dis

appeared. so that the body appears swathed in

a sheath-like garment that completely reveals

its immaculate perfection. The standing images

are generally carved wit h the body bent in a

Praxitelean $-curve. a posture certainly derived

from the repertory of the Indian dance. which

serves to confer an extraordinary vitali ty and

grace to the forn1. In tJ1e Sarnath Buddhas the

bodies become a kind of geometric abstraction

of combined spheroidal and cylindrical shapes,

and the very purity of these textureless smooth

surfaces communicates the idea of the trans-

figured and immortal nature of the body of the

Tathagata. The heads of the Sarnath Buddhas

have a sofl, lyric beauty based on a similar

geometric purity or form. Oocasional inscrip-

tions like that on a Buddha dedicated by

Amitabhyamitra in 474 A.D. seem to indicate

an aesthetic concern for the beauty of religious

icons: '' Image of images. unparalleled for its

merits ... adorned with wonderful an."

A rare example of metal sculpture of the

Gupta period is the small bronze Buddha from

Dhanesar Khera lent by the William Rockhill

Nelson Gallery of Art. ll is a miniature version

of some of the great masterpieces in stone in

which the head recalls the founh and fifth cen-

tury Buddhas of Mathura and the robe is a

combination of the transparcm robe of tbe

Sarnath school with reminiscences of the mll-

uralistic treatment of drapery in Gandhara.

Small images of this type, often repealing tradi-

tional types, were made at centers like Nalanda

as late as the eighth and ninth ceutury: their

export provided a means of spreading Indian

styles of Buddhist sculpture to every region of

the Indian world.

The only parallels in painting for the canons

of beauty observed in Gupta sculpture are the

surviving images in the wall paintings of Ajanta.

Examples dating from the fifth to the seventh

century in Caves I and 9 seem to indicate the

same formula observed at Surnath. with the

Buddha represented in the most simplified

shapes. which in these pictorial counterparts arc

made to appear in relief by a slight reinforcing

of the wiry contour lines with arbitrary shading.

Like the immortal inlluence of the forms and

types of the Greek gods in Western art the ideal

Buddha im:1ge developed in Gupta India be-

came, as it were. the everlasti ng canon for

Buddhist icons throughout the Indian world and

for the entire later development of religious art

in the Far East.

Even as early as the times of Asoka and

Kanishka the Vale of Kashmir was intimately

connected with India. Kashmir was a pocket of

culture that. in its mountainous isolation, per-

petuated the ideals of Gandhara and Gupta art

long after the eclipse of these schools in India

proper. The great era of Buddltism and artistic

expression came under the reign of King Lali-

taditya i11 the eighth century. To this period

belongs the dedication of the monastic estab-

lishment at Ushkur. The ruins of this convent

have yielded numerous examples of stucco and

ierra-coila sculpture. Buddha heads like the

magnificent example lent by Mr. Georgc

Bickford are reminiscent of the type developed

in the Gandharn cemers ofTaxi la and Hadda as

well as of the seventh century Afghan site of

Fondukistan (Figure 5). The free. impressionis-

tic trca1111ent of the hair reminds us of the tech-

nique of Gandhara stucco sculptUJe while the

arching brows and lotiform eyes suggest the

fully developed Gupta formula. The feeling for

roundness and warmth in the modeling of the

facia l mnsk and the softly expressive lips suggest

some of the Indian masterpieces of the fourth

and fifth centuries.

The fina l development of Buddhist art in

India took place under the Pala and Sena

dynasties in the Bengal Valley. The great centers

of Buddhism from the seventh century onward

were at Bodh Gaya and Nalanda, where.

accordi ng to the testimony of the Chinese pil-

grim. Hslian-tsang. the Mahayana faith was at

its zeni th. This final phase of Indian Buddhism

15

t6

wru. dommatcd by the Y:1Jf3)ana doctrine. the

ancestor of Jnpanesc Shu1gon. in which rcliunc:c

on spell>. ritual. and magic diugrams marked the

gradual ab..orption of the rcli!!ion into llmdu-

ism. Some of the more cx.-cult conccph of

Yajrayana. such as the beJc"eled Buddha 3'> an

emblem of the resplendent body 11 hich he

reveal> only to the Bodhi>uttvus. replaced the

simple cult or earlier times. In the ca..c of

man) of the >t:ltue. caned in the hard. blacJ..

stone of Magadha. it b mpo"ble to tell llheth-

er the icon rcpre.ent> the mortul Teacher or one

or the my,tic Buddhm, who had assumed the

mudrm of Sakyamuni'> mortal career. AJ...,ho-

bhya. the L<lrd of the [:1\t. b sho"n m the

fiG. 5. BUDDHA FROM FONDUKISTAN

KABUl MUSEUM. AfGHANISTAN.

mutlm of the Enlightenment. and

Vairocana. the co:,mie Buddha. the

<llwrmacakra mudra of the Fir:,t Preaching.

From the point or \iCII of St)IC. the Buddh:l

tmagc;. from the eighth to the thirteenth century

reveal a faithful imitation of Gupta prototypes.

The cani ng is often dry and mechanical in

execution. There i> an elab01ation of ncccs-

sorie,. and a hard preci;.ion of car,mg seems to

taJ..e precedence O\ er the formal sculpturnt qu-

alillc;. of the 110rk. 1 he stone and bronLe images

of 'alanda. which mu;t have been exported in

quuntitic;,, furnished the models for later Buddh-

ist urt in Tibet and epal and the regions of

South ell>l A>ia. or c'ccpLional beaU!) are the

seventh and eighth century bronzestatuelles from

Bihar"hich perperuateGupta types in miniature.

According to tradition. Buddhi>m was intro-

duced to Nepal by the Emperor Asoka. but the

great period of Buddhism and Buddhist nrt

begins in the eighth and ninth centuries wi th

contacts with the Pala culture of Bengal and the

introduction of Vajrayana Buddhism. The

iconography and forms of Pala an were literally

transplanted to this Himalayan kingdom. prob-

ably in the beginning through the participation

of imported artists. and these forms have been

perpetuated with little change for more than a

thousand years. Although the Nepalese paint-

ings nnd sculptures of the Buddha image repeat

Lhe old types of the Bengal Valley. they are

invariabl) informed with a feeling for

linear rhythms and an precision of

craftsmanship that give them an unmistakable

national character.

Before the appearance of Buddhism. the

religion of Tibet- Bonpo \\3S an antmtsuc

cult including man) elements of sorcery and

sexual The entire culture of Tibet has

been determined by Lhe eh iliting influence of

Buddhi>m. probably first introduced through

alliances wi th Nepal and Chinu in the seventh

century and firmly established by the holy man

Padmasambhava in the eighth. As in ' epal. the

form of the religion adopted by the Tibetans

was the socalled Third Vehicle or Vajrayana.

In the art of such a religious system the simpler

forms of Buddha images arc outnum-

bered by the great host of deities. many of Hindu

origin, thnt crowd its teeming pantheon. So

great was the feeling of rc,erencc and indebted-

ness to Indian Buddhism for its rai>ing Tibet to

a higher le,el of chilization that e\ery effort

was made to retain as close an approximation

as possible to the types and techniques ongt-

nally borro\\ed. This reverence for canonical

types was so firmly rooted that Lhe types and

techniques of surviving paintings of the tenth

century can scarcely be distinguished from

replicas of the same iconography painted in the

eighteenth century. In the course of centuries

Tibetan art inlluenccd by the Buddhist

culture of Khotan in Central Asia and repeat-

edly by Chinese an. especially folio" ing Lhe

conquest of the country b) K 'ang hsi in Lhe

eighteenth century.

Although wall paintings exist in the monastic

ccnters of both Nepal and Tibet, our knowledge

of painting in these Himalayan regions is limited

largely to the great numbers of survh ing ta11kas

or religious banners. Undoubted!) based on

earlier Indian temple icons, the painting of

umkas in Nepal and Tibet was rigidly codified

by iconographic:ll and technical manuals of

Indian origin. The function of these icons in

Vajrayana \\:IS magical, as their

painting itself \\a;, a liturgical rite perfom1ed b)

the artist after yogic meditation on the divini-

ties he was to portray. The were magic

symbols to defend the devotee from the ;nares

:tnd hazards of the world of nature. tO facilita te

for the beholder escape from the world of

C\istence to immaculate celestial;phcrcs evoked

in the picture'>. The concept of religious icons

as emblems of terrible po''er that could O\er-

come karma to transport the worshipper to the

paradise of hi;, choice is identical with the

regard for icon;, in the an of Shingon Buddhism

of Japan.

The actual t)pe> of Buddhas. as \\ell as the

style of painting them. in Nepalese and Tibetan

ta11kas are a faithful perpetuation of the style of

the Pala period. although certain type,, like the

t7

t8

Paradi>c 1conograph). "ere deri\ed

from Central Asia. In the Tibetan painting, of

the eighteenth century something of the precios-

ity of Chinese art or the Ch"ing period recals

itself in the intricate and e\quisite preci;ion of

ornament.

Among the earliest indicauons of the pene-

tration of the Gupta sytle into Further India arc

the Buddhist of Thailand and Cambodia

in the sixth and seventh ccnlUries. These icons.

generall) referred to as the pre-Khmer period.

"ere the accompaniment or Indian

acti,it) m these region;. The beautiful sultues

or the Ovuru,ati period in stone and bronze

follow the ideal of the Sarnath school. including

the transparent sheath-like garment and the

dehanchement of the bod) . The) displn) certain

nathe trail> at the same time. The snail-shell

curls are enormously enlarged. and the feulUres

have a peculiarly beautiful decorative quality.

The metaphorical character or the individual

fe:nure> t> e'agerated. ;o that the e}e> are

e'en more hke actuallotu' petals in shape and

the mouth hth the of an exquisite Horal

shape. The lotiform shape of the eyes is echoed

in the curve of the full The body and head

alike have the simplicit) :tnd sculptural solidity

of Gupta imaes. and the \\hole icon i> 1mbued

"ith a feclmg or tcn:.e ali,enes. that make> u a

veritable emblem or ;creOil) and religious

ecstasy.

The fina l evol ution or the Cambodi:m ideal of

the Buddha image took place during the clti>Sic

centurie> that "itnes;ed the rise or the eapual

and the famou, lO\\ered temple<; of Angkor. In

the head; of Buddha image\ of the l\\elfth and

thirteenth centuries the ultimate indcbtcdnes>

to the Gupta canon i; >ti ll apparent m the

essentiall) spheroidal conception of

the head. What ma) be regarded as a peculiarly

Khmer fo1 mu la or even a cticbl! for indicating

the self-contained bliss and serenity of the En

lightened One appear> in counties> exumple> in

the C)t' closed in rever) and the lips distended

into a long mystenou> smile. Man) of Lhe

Khmer heads of thi> cla.-ic period ha\c a posi-

ti\C suggestion or personality or individuality

within the mould of iconographical and formal

con,cntion. This is perhaps to be explained by

the fact that these "ere at the l>Bme time

idealited of the reignin monarch in

the guise of a demraja or god-king. Whether

the state religion wus Hinduism or Buddhism

the conception of the ruler as the earthly em-

bodiment of the presiding deity of the realm had

for centuries been an C>tablished tenet of belief

in Cambodia. Generally the chief cult image of

the empire sho\\ ing the ;overeign in the likeness

of V ish nu or Buddha was enshrined in a temple

mountain, an architectural symbol of the sacred

Mount Meru of Indian cosmology. at the magic

center of the empire. In Khmer sculpture the

pre' ale nee of the icono11raphy of the Buddha

seated on the coils of n giant serpent and shel-

tered by cobra hood is not entirely a portrayal

of the obscure legend ofSakyamuni"; encounter

"ith a 11uga after hi> enlightenment. lt is a

reference to the legend that the 11agM or serpent

dei tie> \\ere the dh ine progenitors and pro-

of the Cambodian throne.

In general, the heads or Buddhas of the later

ccnturie> of Khmer sculpture tend to a>sume a

more hard linear character in the mci>ed defini-

tion of the features. ln,ariably the mass of the

hair IS separated from the face. sometime> by a

broad band. as though it were a cap literally

pulled over the skull. In certain examples of the

period of the 83)0n m the thirteenth century.

the indi' idual features do not stand out as

5Cparate parts attached to the block of the head.

but melt into this mass. so that to degree

there b a return to the strong plnstic conception

of the earliest period. The best of these late

Buddha masks have a soft. dreamy expression.

a wonderful of a being rapt in inner

contemplation. Although verging on the >ent i-

mcntal. these final Khmer masks are the perfcx:t

;ymbob of the self-contained beatnudc and

benevolence inherent in Buddhi>m

a rclig1on dedicated to the sal\ at ion of human-

it) .

The indigenous tradition of monumental art

in Cambodia came to an end with the linal

Siamese conquest of Angkor in the fifteenth

century. All later development> take place in

Thailand "here the earlier continue to be

repeated with innumerable local variations until

modern times. The ramifications of this >tylistic

evolution of these later centuries arc far too

complex to fo lio" here. The best of the Thai

Buddha> through the sixteenth century >till

rcta&n the plastic integrity of the cltl>>ic >t)lc in

Cambodia. The de,elopment is toward a more

and more decorati,el) stylized concept of the

Buddha mage culminating in the elegant :lllcn-

uated formula achie'ed at Ayudhya. Familiar

a>pcch of this St) le arc the Hame finial that

seem> to carry up"ard the 10\\Cring aucnumion

of the ;lim image. the svelte unmodclcd ;mooth-

nc>s of torso and tubular limbs. the pliant cunes

of elongated lingers. and the in which the

features are a decorative repeti tion of :&re' and

curve>. In its reduction of earlier monumental

often very moving in their pla>tic gran-

deur. to a mannered :.tercot) pc. this

ultimate Siamese style in "hich only grace prc-

'ail; i\ the eastern counterpart of the ncocla;:.&c.

The last outpost of Buddh&;m in the Indian

"orld was the island of Java. where the Sailen-

dra, King of the Mountain and the lord of the

Isles: was the ruler of a great Indonesian em-

pire in the eighth and ninth centuries. Javanese

Buddhism w:ts dependent on the Indian center

at Nalanda. Many bron1c images from Bengal

have been found in the i;land and the prevailiJlg

type of Buddhism was an oiT;hoot of the eso-

teric doctrine of the Pain period.

The great monument of Ja,anesc Buddhism_

one of the \\Onde!'> of the Asian "Orld. ;, the

stupa of Borobudur. Th1s dedicated

to Vairocana. the hi>torical Buddha idealized

in the Dhamwknytt. the eternal body of the

L:m. The "hole >lructure \\ith it> hundred> of

reliefs and statue> wa; conceived as a vast

moudaltt that reveals nil phase' of existence at all

time; and in all place; as ;o m:tny material

manifestations of 1hc divine and universal

essence of Vairocana. Like the painted mondttfas

ofTibet and Japan, Borobudur i'> a magic replica

of the Material and Spiritual world;. "ith each

of its Ooors or store}> reprc>entmg a separate

"orld or plane of life. The 'ecreh of Borobudur

are linked with the identity and function of the

Dh)ani Buddha &magc> that co,cr the monu-

ment from top to bouom. In deep grouo-like

niches on the four >ide> arc in,tallcd the mystic

Buddhas of the four dircct&On> and. on the

upper terrace>. se,ent) -1" o image;, of Vairocana

{Figure 6). These statues of the co;mic lord arc

half hidden under lauiccd bcll->haped stupas as

though to empha>ilc by their partial conceal-

ment the mysterious. ne, er completely revealed

nature of the ultimate reality in a world without

form. "bich is the realm of the Dlwmwkaya.

Presumably the image placed in the closed

terminal Mupa "a> another final form of

19

20

Vairocana enthroned at the cent er of the cosmic

"'heel. at the \Cl) pole of lhe "orld. as the

;upreme manifestauon of \'amx:ana and. as in

Cambodia. a, the e'sence and apotheo>is of

divine kingship.

The style of the Buddha images of Borobudur.

as may be seen even in single detached heads, is

dcri\Cd direct!) from the Gupta style ofSarnmh.

These Buddhas arc made" ith great mathemat-

Ical mccty of measurement from one of the

systems of propomon for sacred images fol-

lowed throughout the Indian world. The finest

of them represent such u beautiful realizntion of

plastic mass and volume. such breathing life and

transcendent spintual clarity of e>.pre.sion that

they ma) r:1nk among the greatest examples of

sculptural genius m the entire world. In these

1mage; there is scarcely any longer the

uon of real flesh. but rather these statues seem

to be made of an imperishable and pure >pi ri-

tual oubstance that marvelously symbolizes in

stone the incorruptible and radiant and ada-

ma1uine nature of the Diamond. the Buddha's

eternal bod).

The extension of Buddhism and it> art to

Central Asia or Turkestnn certainly began as

enrly as the period when the western

pam of the region were under Kushan >uzer-

aint) . The sculpture oft he early >ites lile

Khotan and \hran is the1efore a pro\meial

cxtemion of the Gandhara style ca>tY.Jrd along

the trade route to China. of Buddha

image> from the;e monastic centers and from

rumschuq are mi;understood and conven-

tionalized l.lf the originally Gr:tcco-

Roman type, of Buddha statue> of Hndda and

Ta\ila.

h \\35 ccruunl} on theS<! and later rcpetttions

of this manner at K that the ea1lic<.1

images of China were based. According to

record. m1ssionaries bcarmg >Utras found their

\lay to the Han coun as earl) as 2 B.C. The

famou' legend of the Emperor Ming and his

dream of a golden image lending to the import

or a copy of the famous Udayana statue in 66

A-D. C. probably to be interpreted as a symbol

of the introduction of replicas of famous Indian

to the Far EasL Certainly Buddhism "as

no more than a sporad1c fad in court circles

during the Han period. although it may be

possible to identify crude representations of the

Buddhtl in the Cbiating caves in Szechwan.

The Horcscenee of Buddhism in China

in the Six Dynasties period following the in-

\a;ion of northern China by the Topa Tartars

in 386 A.D. h has been assumed that thc.c

barbarians already had some acquaintance with

Buddhi>111 in their original homeland near Lake

Bnik;tl. lt appears evident that the foreign reli-

gion may have served a political purpose for

these rulers as a unifymg force in opposition to

the native Rligious S}>tcms of Confucianism

and Taoism. just as the Kushnns in India es-

pou>ed the docmne of Sakynmuni as an instru-

ment of imperialism. Although a few bronze

images lil..c the famous gilt bronze from ihc

Brundngc Collection dated 338 antedate the

foundmg of the Wei 0} nasty by the Topa

rulers. the first official patronage of the religion

recorded \1 ith the caning of the rock-cut

temples of YUn Kang under imperial patronage.

YUn Kang is located some thirty miles from

the Tartctr c:tpitnl of Ta-t'ung-fu in the shadow

of the Great Wall. The vn;l undertaking of

he\\ing out more than t\\cnty grotto temple>

\\:IS begun. as the ll'fl S/111 under the

auspu:e; of the priest Tan )30 in -150 and con-

tinued until 494. The concept of carving an

FIG. 6. VAIROCANA BUDDHA.

80R0BUDUR, JAVA.

21

22

- ,

entire monastic e;,tublishment from the living

rock had been anticipated in the Thousand

Buddha Caves in Tun-huang. which. according

to tradition, were consecrated in 366. Indian

prototypes exist for these complexes such as the

Buddhist dwitylls of the Western ghm:. and the

fa mous cave sanctuaries of Bamiyan. There i, a

probable connection between YUn Kang a nd

the Tun-huang caves , incc the Wei Slw informs

u' that in 435. 35,000 families from Liang, the

present Kansu. were seulcd m Ta-t'ung. Of

further interest is the mention that the people of

Linng took their models for buildi ng and stat-

uary from .. the Wes tern Countries," u collcc-

fiG. 7. COLOSSAL BUDDHAS.

YUN KANG, CHINA.

Live tern1 by which the Chinese described the

kingdoms of Central Asia and India as well.

The fi rst dedications at YUn Kang comprised

five colossal Buddhas in memory of the first

rulers of the house of Wei. Such a memorial to

ances tors suggests the infiltration of Confucian

conceptS into Buddhism. lt reminds us that

Buddhism only came to China relatively late in

the development of the civili7.ation and thro ugh-

out ils entire history was hardly more tha n a

ripple o n the face of the sea of indigenous

tradition. Although the inspiration fo r the colos-

sal images at YUn Kang, some of them seventy

feet in height. might have but probably did not

come from the famo us giants at Ba miyan. the

style of this sculpture clearly reveals a Central

Asian origin (Figure 7). it may well be that the

sculptors e mployed at this site were drawn from

the Central Asian colony moved from Tun-

huang to the capital in 435. The Buddha images

of every dimension at YDn Ka ng clearly s how

a tra nslation into stone of the expressionless

round faces of the s tucco images of Kizi l and

Tumschuq. Similarly the drapery reduced to a

network of tape-like bands breaking into forked

folds is a further conventionalizat ion of a man-

nerism found at these sites. Interes ting from the

iconographical point of view is the fact that the

colossi of the western caves a t YOn Kang were

intended to portray the concept of the cosmic

Buddha as described in such sutras as the

Saddltamw Pwtdarikfl and the A 1'0/am.wka.

The famous bronze Buddha Maitreya dated

477 or 486. lent by the Metropolitan Museum

of Art is an illustration of the style of YUn Kang

colossi in a smaller replica. The mantle with its

folds indicated by ribbon-like forms applied to

the surface is characteristic of the Central Asian

formula but the beautiful rhythm of the robe.

spread out like 1\ings unfurled. and the block-

like nbstraction of the head with its wedge nose.

almond eyes. and archaic smile already suggest

the evolution of the Chinese ideal of the Six

Dynasties period.

Toward the close of the period of activity nt

YUn Kang. a much more Chinese conception of

the Buddha image begins to its appear-

ance. The faces become more cubic with sharp

breals bet\\een the planes of the face. and the

completely linear treatment of the drapery tends

to reduce all feeling of the plastic existence of

the body to a llat silhoucuc. Detail> of the cos-

tume, ;uch the trailing passing

through n Jade ring. the cusped necklaces. and

the serrated swallow-tail contour of the flaring

skirts repluce the Central Asian dress. especially

in the imugcs of the Buddha of the Future,

Maitreya.

These tendencies intensified in the

carving of the ea'e temples of Lung-men begun

after the removal of the \\'ci capatal to Loyang

in 494. These images take on a truly Roman-

esque appearance in the that their abstract

linenr style. hier',llic frontality. and disembodied

spiritUality suggest some of the great sculpiUres

of t\\elfth century Europe. Thi> conception of

the figure in geometric and linear teams has

nothing to do "ith an) Indian prototype. The

image has an almost ideographic simplification,

in that the only aspects of significance to the

worshipper the benign mask of the face and

the blessing hand - are modeled in relief. The

rest of the body is flattened out so that it ap-

pears an immaterial rather than a sub>tan-

tially convincing shape. lt ma) be that. with the

removal of the capital and centcr of Buddhbm

to the ancient centcr of Chinese culture at

Loyang. a of the ancient Chinese

feeling for design in calligraphic line and llat

patterned surface, was directed to the making

of Buddhist images. At the same time this ab-

wact mode in the creation of such awe-inspi ring

hieratic forms wns peculiarly appropriate for

expressing the Chinese attitude tO\\ard the

imponed divinaties as strange magacal >pirits

promising all of boons and at the same

time reminiscent of the nl"ays abstractly con-

ceaved deities of the native pantheon.

A new era of purely Indian inlluence in

Chinese Buddhist art begins in the seventh

century" ith the founding of the Tang Dynasty.

This was a moment "hen the subjugation of

rebellions within and barbarians "ithout the

girdle of the Great Wall once more mnde China

:1 great united empire. The military conquests

of T'ni Tsung were followed by even more

memorable triumphs in an. From the seventh

to the ninth ceniUry China. in her material and

spiritual splendor. \\3S the greatest po"er on

earth unrivaled e'en by theempircsof B)Z:Intium

and Iran. In Buddhi;,t art. the haunting abstract

style of the si.\lh century is replaced b) a closer

imitation of lndiun models as a direct result of

the ne\\ diplomatic and religious contacts with

the West.

This renC\\3( of relation, with India begins

"ith tbe ne\\ unit) of China under T'na Tsung

and the subjugation of the Turkt>h khans

beyond the \\C>tern limits of the Great Wall.

The travels nnd >tudies of Hsllnn-t>ang, the

independent pilgrim adventurer. initimcd a new

chapter in the hi;tory of Mahayana Buddhism

10 the Far East. An imentOI') of the sutras

translated b) the Master of the Lll\\ at Ch"ang-

an re, eats how the first real conception of the

23

24

FIG. 8. Gll T 8RONZE BUDDHA.

FOGG ART MUSEUM.

faith of the Great Vehicle was due entirely to his

enterprise. The contribution of HsUan-tsung is

comparable to the discoveries and influence of

the Renaissance humanists on the later devel-

opment of classic learning in the West.

No less important \\ere the official missions

of the Imperial envoy. Wang Hsllan-tS'c, who.

with a corps of artists and scribes. brought back

not only religious texts but what must have been

fairly accurate pictorial records of the holy

place> of India. Of great import for the problem

of the transmission of Indian types to China are

the itemized lists of actual replicas of famous

Indian statues collected by these visitors to the

""Western Countries": for example. Hslian-

tsang had copied the famous sandalwood image

of King Udayana and other famous icons. A

unique wall painting from Tun-huang shows the

transportation of such an Indian image in a

boat across a body of water. A banner from the

library at Tun-huang reproduces copies of many

of the famous sacred statues venerated in the

West in a purely linear technique which seeks.

however, to capture the style of the originals.

A gill bronze Buddha in the Fogg Art Museum

so completely follows a Gandharan original

that it may have been one of these replicas of

famous Indian statues (Figure 8).

IL seems thal a definite merit was anached to

copies- even remote ones - of images at the

sites that were associated with the great cvems

of the Buddha's career. "Something of the

Buddha" was believed to survive in these effigies

related to him: indeed the whole effort of later

Mahayana art in the Far East as in India was 10

imitate by time. place, and form ihe corporeal

manifestation of the absolute truth. The ' 'irtues

of these copies of famous statues from the holy

land of Buddhism lay in the belief that they

incorporated the omnipresence of the Dlwrma-

koyo; something of the Buddha's transcendental

personality remained anached to places where

his human form had appeared as well as to

icons commemorating these appearances. so

that copies of these statues at famous sites were

thought to derive supernatural power from

their relation to originals thus animated by the

Buddha himself.

IL i> not aL all surprising in view of this new

first-hand acquaintance with Indian models

that many examples of rang sculpture are

clearly aucmpts to imiunc the >tyle of the Gupta

period. The >landing imnt:e lent by the Scaule

Art Museum i> n uanslationmto Chine<e terms

of the Sam:uh type" ith the characten>ttc robe.

>rnooth and devoid of and the e:.scntially

spheroida I conception of 1 he head. Only the

feature;. ;.uch the "edge-shaped no;.e and the

archaic smile ;.ccm 10 be a perpetuation of the

purely Chine>c ideal de-eloped in the Sh Dynas

tics period. In the same way. a small bronze

Buddha in the present exhibition is a reduction

of a familiar Pala type.

In some Tang sculptun: like the famous

;tmua!) of T'tcn Lung-;hnn /()) "c

;cnse the presence of the Gupta canon as nn

ultimate precedent but the reduction of the

head and body to e'en more geometricall)

:tbstrnct shapes result> in a loss of the feeling of

warmth and breathing life inherent in the Indian

prototype just the rhythmic and in a sense

naturalistic S\\cCp of the drapery is mon: sug

gesthe of the brush stroke than the car-er"s

tool.

ReHection> of Indian forms are paramount in

the Buddhi>t p:1inting ofT'nng times as may be

seen in the murals of Tun-huang and the lost

\\all painting> of Hol)ujt at Kara \\hich 11ere

painted in the fashionable Indian >I} le of the

eighth century. The annat. of Tang paltlting are

filled with references to artiSt>" ho arc credited

with introducing the le of the We;tem

Countries: They are credited "ith rcpre.enting

forms with :1 \\Onderful illusion of relief. pre

sumably by the use of the type of abwact ;had-

ing found nt Ajanta and in Central A;iu. The

name of \\ci-ch"ih 1-seng i> >Ornetime> attached

to a painting of the Buddha in the M u,eum of

Fine Arts, Bo>ton. in which the figure of

Snkyamuni appears as a free and linear adupt3

FIG. 9. BUDDHA FROM T'IENLUNG.SHAN

FOGG AU MUSEUM.

tion of a Gandharn I} pc.

In C\amples of Tang sculpture in

bronze and >tone "e note the beginning of a

tendency to L'Oncci'e the form in u pictorial

ra.hion. This releals itself Ill the intricacy of the

can in g. the depth of undercutting. and multi

plication of These characteri>tics

would be even more apparent if the images

retained their original polychromy. In the

painted 11ooden image, of Sung and YUan

tomes the depth of can ong and dependence on

color make the.e statues uppear like p:unted

forms transferred to sculpture. Their immediate

25

26

PIG. 10. BUDDHA f ROM f'IE" LUNGSHAN.

FOGG ART MUSEUM,

nntcccdcnts may be the painted clay statues

found '" great number> '" the Liao Dynasty

temples located in Ta T' ungfu. At the same

time the greater delicac) of e'ecuuon. the ;cnti

mental preniness of type. and the v.insome e>-

pre.."ons of both Buddha and Bodhisan'a

t) pe> mal.c it possible to equate these icom

v.ith Baroque rdigiou; art in the We;t. These

Jigurc> with their ingratiating >miles and lan-

guid, tender gestures offer the more immediate

,olace or a religion devoted more and more to

ca;y mean> of sal,ation by dc,otion and oft'cr

ing. to 1mages of such pcr;onablc rcprcsenla

ti\C> of n Buddha no longer remote or inacces

>1ble.

One of the most famou' Buddha images

in Japan is the statue ofS3k}amuni at Seif)oji in

the outskirts of Kyoto ( Fig11rt' //) According 10

the \ ilwngi R,rllkll. thb was n COp) of the

famou; ;andalwood image of King Udayana

rnnde for the priest Chonen Ql K'ai Feng-fu and

brought to Japan in 987. All such copies of this

lcgcndaf) statue of Buddha. it>clf regarded as a

\trllable material facsimi le of were

e>tccmed as onl) potent embodi-

of the Buddha"s earthly manifestation.

The Seir}Oji icon. \\hether 11 is the original

Chinese ;1a1ue or the tenth centuf) Japanese

replica. demonstrates the veritable immortality

of the Gandhara style in the tyliLed reprcsen

tntion or u classical robe in n mesh of closely

pleated folds that had come to symbolize the

"nppling" drapery or the mm1eutous Udayana

ICOn

Throughout the v.hole hi;tory of Chinese

Buddh1>m certain tradillonal type; continue 10

be repea ted sometime> \\ith liule change. The

hronze of the Ming period lent by the Detroit

ln'>titute of Arts is a perfect illuw ation of the

of the famous Udayuna image 111

this nrchaistic reiteration of a drapery style of

the Six Dynasties period. The same miracle-

\\Orl.ing prototype i, rc:prc,entcd in countless

rcphcas made 111 Nepal and Tibet as late as Lhe

t\\entielh century.

The name of Chang S>u-l.ung, a painter

belie,ed to ha\e \\orked in the orthern Sung

penod. 1S anached by tradition 10 a number of

Buddhi;t paintings found mostly in Japanese

collection>. A parliculurly line example of the

style of this rare master is the Buddha Trinity

lent by the Museum. The figures have

a swaying grace and elegance enhanced by the

SOftl) flo\\ing gttrrllents. The p3111tl0g has an

e\traordinnry refinement in e'<ecuuon and. like

Sung sculptured image>. the appeal of these

forms IS 10 their bOfl grace and decorati\c

splcndor. The use or gold leaf. the delicacy or

drnughtsmanship in hnir-tbin line>. and beauty

of calor in thi> and other attributed to

Chang Ssu-kung are so suggesti\e of Japanese

Buddhist painting of the Fujhnra period that

one wonders if this nebulous artbt may ha' e

influenced the idcttl; or that mo;t exquisite

period of Japanese religious an.

The kind or delicate superficial refinement

alread) exemplified in Lbe painting. b) Chang

Ssu-kung wa> perpetuated "ell into the late

Ming and Ch'ing periods. The example in the

pre>crH collection rc>eals a desiccation and

hardening of the drawing of ib prototype. and

nt the same time the tmage is lost in a \\eallb of

>urfa<-e decoration. The fascinaung and elabo-

nnc architectun: or Sakynmuni"s throne vies for

;mention with the bhape of the Buddha himself.

As in the declining phase of religious an in so

man) pans of Asia and the We,t. the 'irtuoSII)'

of the technical performance take> precedence

O\er the no longer meaningful icon.

Ch'an or Zen Buddhism >pecifically

denied the validity of ritual and attachment to

icon5. the Buddha image seldom appc-Jrs in the

an of tlus purified philosopbjcaJ >CCt e'cept in

such occasional temple banners a; the fnmou>

painting of Buddha b) Liang K 'at. formerly in

the collection of Count Sakai. in which the

MU!>ter is shown. not in any U>Unl iconographi

cal form. but as a "ild-eyed. ragged 'agabond

C\emrlif)ing the rugged austerit> and unonho-

dox po" er of Zen tdeals.

The traditional date for the introduction of

to Japan is the year 552. when the

kmg ofKudnrn in Korea sent n gift ora Buddha

tmage and to the reigning emperor.

The national religion of Japan at thi> moment

\>US the cult of the Shinto Jwmi stmlll. the

of elements und natural forccb. upon whose

favor the ver) >tabi)j ty of the empire and indi

'idual "ell-being depended. lt not strange

that the mtroduction of this foreil!Jl faith .hould

ha\C aroused a; "ell as the fear of

offending the native dcitie<. The Emperor b

reported to have spoken us follows: .. The

countenance of this Buddhu "hich has been

presented .. 1> of severe dignity >uch as "e have

ne, er seen before. Ought it to be \\Orshipped or

not"! Shall Yamato alone rcfu;e to \\Orship it'!

"'Those \\ho have ruled the Empire in this our

state have always made n their care to worship

In spring. summer. autumn. aud "inter. the 180

gods of hea,cn and earth. nnd the gods of the

land and of gram;. lf ... \\C \\Cre to in

their stead foretgn deities. it muy be feared thnt

we >hould incur the wrath of our national

lt was not long before an outbreak or pc>ti-

lence seemed tndeed to indicate the displeawrc

of the sun godd=. and >O the>e first tokens of

Buddhbt ritual \\ere fonhwnh thro"n into the

>C:t ut Naniwn. lt \\:lS onl) in the beginning of

the seventh century under the Empress Suiko

and the enlightened Prince Shotoku that Bud-

dhism" ith their fer,ent patronage "as acecptcd

in Japan. The founding or the carlic.t ;hrinl'S nt

Gangoji and Hor) uji in the t\arn plain date

from thi$ period. as do the earliest Buddhibt

icons to be made in Japan. Among the earliest

;urviving religiou; images arc the golden brontc

trinities of " aJ..u;hi and ShaJ..n by a certain Tori

27

28

fiG 11 BUDDHA FROM SEIRY0J1.

JAPAN.

Busshi dedicated at Horyuji in 607 and 623

/1). The cult of Yakushi

guru). the Buddha of Healing. wa. one of the

fir.t to gain popularity in Japan because of the

miraculous cures offered by this divine physi-

cian.

Tori Busshi 11ns the grandson of n sculptor

11 ho had emigrated from the kingdom of Linng

m South Chma in 522. The SI) le of Tori's reli-

gious images marks the introduction to Japan

of the forms and technique, of Chinese Bud-

dhi>t !>Culpture of the Six Dynasties period. The

central Shaka of the trinity dedic-.1ted m mcmol)

of Shotoku Taisbi in 623 the slight

modifications thi> style has undergone in its

translation to Japan (Figure 11). The image is

domonatcd by the two plastoc elements of the

block-like head and the great hand rnised in

blessing: the body itself, as in continental

>Culpt urc. uppears almost dematcrializcd under

the intricate surface linear rhythms of the orn-

pcry. The face itself is a darkly brooding mask,

;ugge,ting the mysterious and onscrutablc prop-

erties attached to Buddhism by the Japanese

of the sc1enth century. Perhap:. the mo;t Japa-

ne>e features of this icon nre the delicac) and

preci:.ion of Lhc: craftsmanship and the abstract

beauty of design in Lhe flame halo and the

tlo\\cr-likc comolution> of the pattern of the

drapery falling over the dais. Although many

icon> of the Suiko period have the same rather

and awe-inspiring coutcnancc;, the

fncial rnn>ks of a certain number of thcoc curly

,tntuc; have a wangcly child-like cast. ti lled

"ilh n radiant expression of innocence nnd

cnndor. This typically Japane;c quality is des-

cribed by words like ltt!imt'i or mean-

ing litcmll) "radiant Hatnes>.'' or simplocoty and

and e'er) thing opposue to the dark and occult.

fiG t2 SH,KA lRtNI!Y, HORYUJI.

NARA, JAPAN

30

The terms may also be applied to Lhe specifically

flat. pancrnized conception of the images as a

whole and the decorative manipulation of sur-

face design. This is a quality which continues to

appear as an immortal thread throughout the

whole Inter fabric of Japanese art.

By the end of the seventh century the manner-

isms of Six Dynasties art had been replaced by

an assimilation of the Tang style. Japanese

Buddha images of the Hakuho and Tcmpyo

periods the same refinement of con

tinental models begun in the Suiko era. The

great black bronze Trinity of Yakushiji is the

metal counterpart of Chinese stone sculpture of

the seventh and eighth centuries 13). The

FIG. 13. YAKUSHI, YAKUSHIJI.

HARA, JAPAN.

central Buddha has the feeling of volume and

weightiness of Tang statues set off by the fluid

naturalism in the disposition of the drapery

folds.

The painted equivalents of such eighth cen-

tury masterpieces were the Buddhas of the Four

Paradises of Horyuji Kondo. the famous wall

paintings destroyed by fire in 1949. The iconog-

raphy of this cycle illustrates the complexity of

Japanese Buddhism in the Hakuho period. The

four Buddhas portrayed - Shaka, Amida,

Miroku, and Yakushi - form a mandala or

magic diagram of the four directions. each with

its heaven presided over by a divine Buddha. It

may be assumed that the basis of this icono-

graph teal arrangement is not to be found in an)

one text but in n number of difTercnt sutras

popular at the time. The style of figu res

like the Amida has nothing Japanese about it :

the form itself the rang ''all paintings

at Tun-huang. and the shading of the robe in

bands of dark pigment reinforcing the lines of

drnpery is a Chinese technique that may be seen

in such famous rang origi nals as the Scroll of

the Thirteen Emperor;, by Yen Li-pen. Some of

the small figure> of reborn souls in thts compo-

;,ilion are so strong!) Indian in fot m and in use

of a heavy chiaroscuro that they might have

been inspired di rectly by Indian originab.

The Tempyo period was an age of secular and

religious po"er and splendor rivaling the Tang

ci' ilizatioo of China. China continued to pro-

vide the models for C\ery phase of Japanese art:

the capital at Nnra was laid out on the plan of

the Chinese city of Ch'ang-an and the Oaibutsu.

the giant Buddha of Todaiji, was inspired by

the colossus dedicated by the Empre.s Wu at

Lung-men. ln the eighth centuf) Buddhism and

Shin to were reconciled in the tenet that the uni-

versal Buddha Vairocana and the sun goddess

Amuterasu were only different mani festations

of the same cosmic splendor. The doctrine of t he

Bommokyo. in which the universal Buddha is

the center of the 1\0rld system with all phenom-

ena. spiritual and material, emanating from

hi m. provided a religious parallel for the polit-

ical structure of Japan with the emperor at the

summit of the social and religious S)stem of the

realm.

Many Japanese Buddha images such as the

famous Roshana at Kanimanji arc informed

with a feeling of expansive volume. described by

the Japanese term ryo. which approximates the

suggestion of the presence of an inner breath or

pneumatic force of Indian image>. It is well to

note that even Matues of >uch colossal siLe

reveal somethi ng of the expres>ion of gentleness

and ingenuous S\\eetness that emerged a; 11

Japanese trait in the \ery earliest period of Bud-

dhist art. For the presentauon of sheer plastic

mass. the conception of sculpture as an exercise

in inter-locking abstract volumes proclaiming

the solidity and weightiness of the form. the

masterpieces of Japanese caning of the eighth

century "ere scarcely equated b) the sculptors

of rang China. The Tempyo masterpieces hae

a classic nobility and serenity that was to be

emulated in many later periods.

The dangers inherent in the ever-encroaching

inRuenceofthe Nara priesthood on the admins-

stration of the empire. led to the removal of the

court to K)oto in 794 and the withdra\\al of

further govcrnmettt support of the Buddhi>t

church. The whole program of Buddhism in

Japan had perforce to be revised with the specif-

ic end of gaining the support of the nobilit) m

the new capital. This aim 1\35 achie'ed through

the appeal of the cults of esoteric Buddhism.