Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Shimura tsl561 Sum09 Finalproj Notitlepage

Încărcat de

api-233476576Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Shimura tsl561 Sum09 Finalproj Notitlepage

Încărcat de

api-233476576Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

SDLL 1 Self-Directed Language Learning (SDLL) is a topic that should interest us all [1].

From my observations of students learning ESL/EFL, it is the students who are ready and willing to study independently that learn the most efficiently. This paper exposes some of the research I have discovered in SDLL and ideas for its implementation in an English language learning program. As a full-time intensive English language program instructor at St. Norbert College, one of my responsibilities is that I oversee the investigation of establishing a computer-assisted language learning (CALL) lab for our students. The initial step the institute took was the installation on computers throughout campus of interactive software that corresponds with the grammar textbook we use in our classes. This learning tool has proven to be beneficial for many of our students as seen from feedback obtained through surveys and interviews. Because this program was available across campus, the trial CALL lab, (a computer lab reserved specifically for our students during set hours each week), was not being utilized. Recently, our institution has been investigating the addition of a lab for independent ESL and foreign language learning. In order for this lab to become a useful learning tool for our students, I see a need for our students to be more self-directed in their learning and for the CALL lab to provide the resources necessary to meet their needs. During my observations for Shenandoah Universitys TSL 531 course, I came across the term self-regulated learning and observed the results of this type of instruction with kindergarten and first grade students. These young learners entered the ESL classroom everyday knowing exactly what, where and how they needed to study. The instructor served as a facilitator. It is the eighteenth chapter of Doughty and Longs

SDLL 2 book (2003) that some of these concepts like learning strategies, autonomy, and selfregulated learning unfolded with more clarity in my mind. The focus of this research project is on autonomous self-help training within SLAto determine whether it has value for SLA and to investigate the facilitation of it. In this paper I will define terms related to self-regulated learning in SLA, give examples of the facilitation of selfregulated learning, and provide ideas for future research for self-directed learning. The fields of educational psychology and linguistics have coined similar and yet varying concepts of independent learning with different terms. Educational psychologists prefer self-regulatory learning over learning strategy, the preferred term for linguists (Dornyei, as cited in Rivera-Mills & Plonsky, 2007). The concepts certainly overlap, as can be seen in Maroro, Oxford, and Wendens statement that there is a positive relationship between autonomy and learning strategy use because they encourage selfdirected learning (as cited in Rivera-Mills & Plonsky, 2007). Learning strategies can be defined as the mental and communicative processes that learners deploy to learn a second language (Nunan, 1999, p 55). Components of learning strategies include the cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral and affective while self-regulatory learning includes these four components plus others (Manchon, 2008). Learning strategies are defined in specific behaviors in order to be teachable whereas self-regulations central focus is in goal setting and action on those goals, these including the use of strategies. Linguists have chosen to separate self-regulatory learning into concepts of autonomy and learning strategies. Within TESOL, other terms like strategy training, learner training, selfdirected language learning, learning-to-learn training (Rivera-Mills & Plonsky, 2007) and strategy-based instruction (SBI) are employed in addition to learning strategies.

SDLL 3 Autonomy and learning strategies have been points of interest in recent years as they seem to have potential benefits for SLA. Learner autonomy and SLA have been shown to have positive correlations (Rivera-Mill & Plonsky, 2007). Wenden (1985) was one of the first to emphasize the importance of learning strategies for autonomy and autonomy for SLA (Brown, 2007). OMalley and Chamot (1990) found that more effective learners used strategies more frequently and with more variety (as cited in Nunan, 1999). Heikkila and Lonka reported in 2006 that learning style affects their learning performance (Herington & Weaven, 2008, p. 112). Some of the factors/benefits of SBI in SLA are related to the use of learning strategies is the development of metalinguistic awareness, increased awareness of learning strategies and styles, increased motivation, a linear or curvilinear proficiency level, improved perceptions of self/of instructor (Rivera-Mills & Plonsky, 2007). Joe Blum, M.A. TESOL, recently commented in the TESL-L listserve that two-thirds of students his students in Orlando, Florida are ready for self-directed learning [2]. The other third need direct instruction. While all students will benefit from SBI, it is this latter group that requires it the most to be able to learn how to become efficient language learners. The former group is ready to engage in self-directed learning. Before implementing any type of independent learning initiative such as in a CALL lab, the teacher or institution must determine whether students are ready for selfdirected language learning. Recent discussion on the TESL-L listserve has revealed a tool that was developed over thirty years ago by Lucy Gugielmino, the Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale/Learning Preference Assessment (SDLRS/LPA). The SDLRS is an assessment that measures the attitudes, skills and characteristics representative of an

SDLL 4 individual who is ready to direct his/her own learning. The assessment has been used in more that ninety doctoral dissertations and has been deemed useful for measuring readiness by Delahaye and Choy (2000, as cited in Guglielmino). The LPASD/LRA web page claims that reliability of the assessment has ranged from .72 to .96 over a twentyyear period (Guglielmino). The completed assessment places an individuals preparedness into one of three categories: below average, average, and above average. The average and above average categories are the areas where Joe Blum, as mentioned earlier, has generally found two-thirds of his students, ready for self-directed learning [2]. While this is the only assessment of this type I am currently aware of, its discovery certainly has given me hope that a fairly accurate tool for determining learner readiness is available prior to orientating students to a CALL lab program. The students who are not ready can wait until they are ready before attending an orientation. The other advantages of the LPASD/LRA are that it is available in a condensed and simplified version for nonnative English speakers and available in twenty-one foreign languages as well, making it appropriate for all levels of language learners and for learners of other foreign languages as well (Guglielmino). In the future, I hope to explore this assessment and other selfdirected language learning readiness assessments further. Upon determining the readiness of language learners for self-directed study, I envision that instruction in self-directed study and a presentation of available options for learning and then use strategies to achieve their goals. Kenton Sutherland, and ESL instructor with over fifty years of experience, in a recent TESL-L forum, provided the following resource suggestions for self-directed learning: recordings, movies, books, newspapers, magazines, internet resources, and conversation with native speakers (i.e.

SDLL 5 conversation clubs, English corners, lectures, and visiting specialists) [1]. Students can also develop a greater sensitivity to the learning process through reflection, both personal and in small groups. Journals can be utilized to increase the students ability to articulate goals and desired methods of learning. Self-monitoring can be accomplished through portfolio collections. Reflection, self-reporting and self-monitoring lead to a greater ability to connect the reading, writing, speaking, listening, grammar, and content-based coursework students are engaged in (Nunan, 1999). Reflecting on this research and knowledge gained from this project leads to the application of it to my own teaching responsibilities, specifically the development of SDLL as a component of a CALL lab. First, a method of determining student readiness for SDLL must be utilized, one of which was discovered as a result of this SLA project. Once other assessment methods are explored and one is chosen, the implementation of it will be the easiest part of the SDLL/CALL lab project. Next, those who are ready for self-directed language learning will need guidance. An orientation would guide students in setting their own goals and provide them with tools for striving to meet those goals. Some resource ideas were listed in this paper, representing an incomplete list of potential resources that need to be developed further and presented in a user-friendly format. Finally, a method of assessment will need to be developed to aid the student and the instructor in determining the effectiveness of the program. Due to the complexity and scope of this CALL lab initiative, collaboration with other departments on campus will be essential to its success. To sum up, it is through the assessment of self-directed learning readiness, the setting goals, the provision of resources, and the evaluation of progress in meeting the

SDLL 6 goals that autonomous language learning can be encouraged to increase SLA effectiveness for our students. With the variation in terminology and lack of consensus for linguists in defining this concept of autonomy in language learning, research in this idea of independent language learning will continue to be difficult to find and apply. Despite this, there seems to be significant interest in SDLL, autonomy in learning, and SBI, dating back thirty years to the present. With this persevering interest in self-directed learning, not only for linguists, but also for professionals in the field of education, it is my conclusion that SDLL is beneficial for learners and that the pursuit of further research and sharing of methods for facilitating SDLL will be worthwhile.

SDLL 7 References

Brown, D.H. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching. White Plains, NY: Pearson Education. Doughty, C.J. and Long, M.H. (2003). The handbook of second language acquisition. Malden, MA: Blackwell. Guglielmino, L. Language Preference Assessment. 17 Jul. 2009 <http://www.lpasdlrs.com>. Herington, C. and Weaven, S. (2008, December). Action research and reflection on student approaches to learning in large first year university classes. The Australian Educational Researcher, 35 (3), 111-134. Manchon , R.M. (2008). Taking strategies to the foreign language classroom: where are we now in theory and research? International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 46 (3), 221-243. Nunan, D. (1999). Second language teaching & learning. Boston,MA: Heinle & Heinle. Rivera-Mills, S.V. and Plonsky, L. (2007). Empowering students with language learning strategies: a critical review of current issues. Foreign Language Annals, 40 (3), 535-548. TESL-L References [1] Date: Fri, 17 Jul 2009 14:04:47 EDT From: Kenton Sutherland <KSuther929@AOL.COM> Subject: Re: Self-Directed Language Learning [2] Date: Thu, 16 Jul 2009 1:41:18 EDT From: Joe Blum <jjblum@MINDSPRING.COM> Subject: Re: Self-Directed Language Learning

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- How To Build A Memory Palace Review & Memory Palace WorksheetsDocument49 paginiHow To Build A Memory Palace Review & Memory Palace WorksheetsAlexa Geanina100% (2)

- What's IQDocument11 paginiWhat's IQzoology qau100% (1)

- Photography Degree HandbookDocument21 paginiPhotography Degree HandbookRyan Malyon100% (1)

- Abm11 - q1 - Mod5 - Solving Problems Involving Proportions - v5 - R.OlegarioDocument24 paginiAbm11 - q1 - Mod5 - Solving Problems Involving Proportions - v5 - R.OlegarioDatu Mujahid BalabaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eng7-Q4-iP13-v.02 Analyze Relationships Presented in Analogies and Supply Other Words or Expressions That Complete An AnalogyDocument8 paginiEng7-Q4-iP13-v.02 Analyze Relationships Presented in Analogies and Supply Other Words or Expressions That Complete An Analogyreiya100% (1)

- Assessment and Evaluation of Learning Prof - Ed PDFDocument20 paginiAssessment and Evaluation of Learning Prof - Ed PDFDiannie SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- TRF Movs For Objective 10Document4 paginiTRF Movs For Objective 10Caitlin AbadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accomplishment ReportDocument1 paginăAccomplishment ReportCathyren Capizonda Teves93% (15)

- Nursing EducationDocument18 paginiNursing EducationMakhanVermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume Dawnshimura May 2017 NoaddressDocument3 paginiResume Dawnshimura May 2017 Noaddressapi-233476576Încă nu există evaluări

- PricingDocument1 paginăPricingapi-233476576Încă nu există evaluări

- Sample Course Objectives PageDocument1 paginăSample Course Objectives Pageapi-233476576Încă nu există evaluări

- cc3 Toc SVDocument6 paginicc3 Toc SVapi-233476576Încă nu există evaluări

- cc2 PG TocDocument3 paginicc2 PG Tocapi-233476576Încă nu există evaluări

- Article 3Document20 paginiArticle 3Rokia BenzergaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classroom Observation Assignment-Form 1 - Samir Ahmadov Educ5312Document3 paginiClassroom Observation Assignment-Form 1 - Samir Ahmadov Educ5312api-302415858Încă nu există evaluări

- Robin95 (RESEARCH AND PRAGMATISM IN)Document7 paginiRobin95 (RESEARCH AND PRAGMATISM IN)Tom ArrolloÎncă nu există evaluări

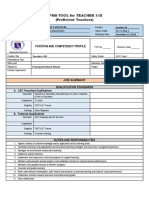

- Rpms Tool For Teacher I-Iii (Proficient Teachers) : Position and Competency ProfileDocument26 paginiRpms Tool For Teacher I-Iii (Proficient Teachers) : Position and Competency ProfileRheinjohn Aucasa Sampang100% (1)

- Smart Class ProjectDocument36 paginiSmart Class ProjectRiya Akhtar75% (4)

- Usmle StepDocument4 paginiUsmle StepJennifer LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABE Level 4 Diploma in Business ManagementDocument2 paginiABE Level 4 Diploma in Business ManagementBayoh Shekou100% (1)

- Arts Integration SpeechDocument4 paginiArts Integration Speechapi-350187114Încă nu există evaluări

- GEC 001 WLAP (Revised-Oct. 2018)Document18 paginiGEC 001 WLAP (Revised-Oct. 2018)rick14344Încă nu există evaluări

- The Teacher in The Classroom and CommunityDocument11 paginiThe Teacher in The Classroom and CommunityLeany AurelioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final PPT ANNDocument30 paginiFinal PPT ANNWishal NandyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math Assignment 03 - Final DraftDocument6 paginiMath Assignment 03 - Final DraftJohn KakomaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ramakrishna Mission Vidyapith: Information Regarding Admission To Class XI For 2018Document2 paginiRamakrishna Mission Vidyapith: Information Regarding Admission To Class XI For 2018abhishek kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- ID Deskripsi Kesalahan Struktur Berpikir Si PDFDocument10 paginiID Deskripsi Kesalahan Struktur Berpikir Si PDFJulita WindayuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supportive Phrases For DiagnosticDocument1 paginăSupportive Phrases For Diagnosticapi-284308390Încă nu există evaluări

- BA 501 - Social Responsibility and Good GovernanceDocument8 paginiBA 501 - Social Responsibility and Good GovernanceVal PinedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum Planning For All Learners Applying Universal Design For Learning UDL To A High School Reading Comprehension ProgramDocument11 paginiCurriculum Planning For All Learners Applying Universal Design For Learning UDL To A High School Reading Comprehension ProgramFabiana PiokerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dressing UpDocument28 paginiDressing Uptutorial 001Încă nu există evaluări

- KMAT Kerala 2018 Answer Key FEB 4Document2 paginiKMAT Kerala 2018 Answer Key FEB 4Anonymous J5L1THzrbw0% (2)

- Fontys University of Applied SciencesDocument3 paginiFontys University of Applied Sciencesnqh2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Training and Development Program Design & Proposal: In-Service Training For Teachers 2020Document5 paginiTraining and Development Program Design & Proposal: In-Service Training For Teachers 2020Precious Idiosolo100% (1)