Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Nichole M Oltz Community College Q A Paper

Încărcat de

api-241244976Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Nichole M Oltz Community College Q A Paper

Încărcat de

api-241244976Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Running head: SCORE OR PENALTY

The Community College Mission vs. Athletic Programs: Score or Penalty? Nichole Oltz Ball State University

SCORE OR PENALTY Introduction

More than ever, people are turning to community colleges to fulfill their education needs. Many demand the complete education experience advertised as the mission of higher education. Consequently, American community colleges are charged with providing this service while meeting the needs of their diverse population. One of the ways institutions have been able to meet this order is the implementation of athletic programs. Approximately 60 % of community colleges host athletic teams (Noonan-Terry & Sanchez, 2009). These programs offer their participants higher academic standards and support, retention, degree completion, and transfer efforts, key opportunities for community engagement, as well as citizenship development and workforce skills preparation. Through these services, community colleges strive to give these students the support necessary to successfully pursue their athletic and academic aspirations in addition to enhancing their personal and professional development. Athletic programs are, arguably, one of the most effective co-curricular ways to address the pressing student population questions institutions are often faced with, such as first-time and male enrollment numbers, diverse access, successful retention, transfer and/or graduation rates, life-skills development, school-connectedness, and academic achievement. Indeed, these resources are critical for student success, however, how effectively and holistically do they support the mission of the community college system? Community College Governance Commission on Athletics The oldest governing body for community college athletics is the Community College League of Californias Commission on Athletics (COA), established in 1929 under the name California Junior College Federation (California Community College Athletic Association,

SCORE OR PENALTY

2012). The COA Board is solely responsible for the state-wide administrative and financial tasks as well as the policy evolvement and implementation leading the nearly 25,000 student athletes in the state of California. The council also consists of a 28-member Management Council comprised of athletic directors, academic advisors, coaches, state council on physical education, sports information directors, athletic trainers associations, and representative commissioners from Californias northern and southern conferences, tasked with managing the day-to-day operations. In 2001, the COA became the California Community College Athletic Association. It currently regulates the athletic programs and their athletes in the 107 colleges in 71 districts in the state. California community colleges athletic programs boast many primetime athletes such as baseball greats Jackie Robinson, Tom Seaver, and Duke Snider, and household football names like Keyshawn Johnson, Coach John Madden, and National Football League Commissioner Pete Rozelle, in addition to numerous Olympic athletes. National Junior College Athletic Association The second oldest of the governing entities for community college athletics is the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA), established in 1938 (National Junior College Athletic Association, 2013). It is currently the second largest collegiate athletic governing institution, second only to the National Collegiate Athletic Association. According to the NJCAA, in the 2012-2013 academic year there were over 58,000 students participating in the more than 520 community college athletic programs in the United States (Teague, 2012, p.5). The sports offered by the NJCAA include: baseball, softball, basketball, bowling, cross country, football, golf, half marathon, ice hockey, indoor and outdoor track and field, lacrosse, soccer, swimming and diving, tennis, volleyball, and wrestling (National Junior College Athletic

SCORE OR PENALTY

Association, 2013). These programs are primarily concentrated in the Midwest, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia (Ashburn, 2007, p.58). Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges The final governing body is the Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges (NWAACC). The latest of the three, it was established in 1946 as the Washington State Junior College Athletic Conference (Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges, 2013a, p. 2). Presiding under the motto of Character, Competition, Community, today, they regulate the activities of the 34 member community colleges and 280 team programs in the states of Washington and Oregon. According to the 2011-2012 NWAACC annual report, 3,700 of the states community college students were student- athletes that year. This association offers student athletic programs in cross country, track and field, baseball, basketball, softball, golf, soccer, tennis, and volleyball (Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges, 2013b). Enrollment Benefits Athletic programs increase enrollment in community colleges. Many high school students are academically or athletically underprepared and geographically restricted due to work or family, yet still want to pursue their athletic aspirations. These students are often over-looked by four-year athletic programs or cannot handle the taxing schedule and environment such programs come with. Community college athletic programs offer these prospective students the opportunity to participate in athletics and pursue a degree. A large part of this population is firsttime students. In fact, a 2002-2003 program landscape study showed student athletes made up 20 % of the first-time student population at participating community colleges (Bush, Castaneda, Hardy, & Katsinas, 2009, p. 7). Additionally, there tend to be more mens programs than womens programs at these institutions. This assists community colleges in the enrollment and

SCORE OR PENALTY

retention efforts of male students, a critical issue in higher education. An added benefit to the institutional enrollment growth is the increased funding from tuition, since scholarship variants are only given to Division I and II student-athletes (National Junior College Athletic Association, 2013), and student services made possible by athletic programming, thus giving the college and its student body a more complete college experience without relocation, enrollment tenure, and cost. Academic Benefits The NJCAA mandates and enforces academic standards for the community college athletic system and its participants. According to the eligibility requirements, students are required to maintain a minimum 2.0 grade point average and be enrolled full-time, 12 hours, in an institution to be eligible for participation (Champion, 1990). They are also obligated to make progress towards graduation (National Junior College Athletic Association, 2013). Students are only allowed to participate in two seasons of their desired sport, however, before they are allowed to begin their second season a student must have completed the necessary hours and grade point average. The NJCAA requires semester hours and grade point averages be examined every semester for accountability and improvement in an effort to assure students progress towards degree or certificate completion. The rules also assist a transfer-aspiring student to maintain the requirements needed to enter a four-year institution, further supporting the community college mission of student success. With the numbers of academically underprepared and/or first-time college students, as well as the time-demanding schedule being a collegiate athlete entails, institutions provide many student services to assist in the attainment of the aforementioned academic standards. These programs include: eligibility monitoring, academic advising, tutorial assistance, and personal and career counseling, among others (Storch

SCORE OR PENALTY

& Ohlson, 2009, p.76). According to Storch and Ohlson (2009), the services provided often surpass those of four-year colleges and universities. For example, academic advising helps students navigate through the opinions and suggestions presented by their peers and offer students referrals to other services when necessary. Athletic academic advisors also tend to be more intrusive in their advising style, an added benefit for an underprepared student. Also, because the breadth and depth of collegiate athletic rules, not every academic advisor is qualified to serve student athletes. Consequently, most of these students will see the same counselor over the entire course of their enrollment. Furthermore, because of the lack of funding, many coaches also have a faculty positions at the college. This sense of connection to the faculty encourages student interaction and retention. The personal connection and services foster an enhanced institution-student relationship and push the individual to continue until completion. These students profit from this relationship and the other support services provided, further enhancing their collegiate experience and facilitating their academic and personal developmental growth and success. Community Engagement Campus Community Athletic programs not only assist student athletes, they also open avenues for other student activities (Noonan-Terry & Sanchez, 2009). Student organizations such as cheerleading and marketing are made possible in addition to potential sports medicine, sports marketing, and fitness internships, among others. Some community colleges even have bands, yet another outlet for institutions to offer its students a common four-year institution favorite service. Having these programs gives students an opportunity to be active participants of their college and develop a sense of connectedness. Many community college students often feel detached from their

SCORE OR PENALTY

institutions because of their schedules and lack of involvement. By creating more services, encouraging involvement , and developing a sense of school pride and community, students will enjoy their experience more and become more invested in their institution.; consequently, causing an improvement, even if minimal, in retention. Student activities are integral to the education process and compliment the mission of the community college system (Lawrence, Mullin, & Horton, 2009). Involvement in co and extracurricular activities has proven to be an invaluable tool for students academic, personal, and professional development. Participation allows individuals to acquire and cultivate skills such as: cultural competence from working with diverse populations, group processing skills, decision-making and management abilities, bureaucratic governing experience, networking, interpersonal skills, self-confidence, and, possibly, public speaking (Hajart, Toscano, Horsley, & Del Re, 2007, p.31; Hanks & Eckland, 1976, p. 271) . These skills are instrumental to the development of citizenship and fulfill the demand by employers for mature, prepared workers. By offering community members opportunities for growth, community colleges accomplish their mission of preparing students for life after college and training a skilled workforce. The Involvement Theory of Alexander Astin examined the degree of learning and development growth induced by a students environment, such as academic and social experiences (Astin, 1984). Astin proposed the levels of aforementioned growth will occur to the degree a student is able to physically and psychologically invest in their educational experience. With this in established, the value in the collective benefits offered to a community college student through various athletic programs and their related and/or supporting organizations is further sustained.

SCORE OR PENALTY

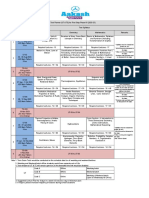

Similar to the Involvement Theory, Astins Input-Environment-Outcome model [See Figure 1] (Astin, 1993a, p.18 )can also be used to showcase the value of such programs (Astin, 1993b). It proposes a students educational outcomes are a direct result of their pre-collegiate experiences and characteristics as well as their involvement and experience influences while in college. Like the Involvement Theory, the environmental factors are deemed pivotal to successful growth, specifically in this case, among other citizenship traits, civic attitudes and behaviors foreshadowing a students social values and activism along with volunteerism and other charitable involvement [See Figure 2] (Gayles, Rockenback, & Davis, 2012, p. 538).

Figure 1. Astins Input-Environment-Outcome Model. Retrieved from (Astin, 1993a, p.18)

Figure 2. Civic Values and Behavior Conceptual Model. Retrieved from (Gayles, Rockenback, & Davis, 2012, p. 538) Local Community Community engagement is at the heart of community colleges purpose. Athletic programs support this mission in numerous ways. They help bridge the town vs. gown disconnect many surrounding communities feel toward nearby institutions (FAQ, 2007), or, as Lawrence, et al. (2009) states, community college athletic programs are the link between the immediate campus family and the larger community. Most, if not all, community college

SCORE OR PENALTY

athletes are local residents. The proximity to home, small collegial environment, and potential for athletic scholarship, if the school has a NJCAA Division I or II team or are a member of the Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges, are all appealing factors (Schneder & Messenger, 2012, p. 805). By recruiting and developing local talent, they assist in the development of the young adults in the community and offer residents a chance to continue to watch the local stars they may have enjoyed while those students played in high school. Another appealing factor for the students, and an added benefit for the spectators, is the probability of immediate playing time. This, according to a survey conducted by Schneder and Messenger (2012), was one of the reasons student-athletes choose to attend their respective colleges. Offering local residents the opportunity to pursue and accomplish their athletic and academic aspirations simultaneously, while staying close to home complies with the mission of community colleges. Recruiting local residents also gives families and friends the opportunity to support the athletes, a chance they may not have otherwise been afforded if the individual attended a school out of the area. In an interview with an administrator at College of DuPage in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, they stated, their athletic program was instrumental in boosting student morale and the students and the community were very involved in athletic events; they even tailgated for the schools football games (Interview E, personal communication, October 2, 2013). Additionally, community college athletic programs impact the economic growth of the community. Local facilities are often contracted for practices and games if the school does not have amenities (Lawrence et al., 2012, p. 45). Also, because community colleges have limited funding, local businesses often develop partnerships with the school to supply player and team equipment, clothes, and other necessities. Student athletes, both local and out of district or state, often rent from local apartment and housing communities and often make purchases from local

SCORE OR PENALTY

10

restaurants and businesses. Also, the opposing teams may purchase hotel rooms, patronize local restaurants, and buy other local items during their visit. Collectively, these efforts create new opportunities for residents, heightened community involvement, facilitate a sense of school pride, and ultimately influence the enrollment of students and their retention rates in their pursuit to accomplish their mission (Noonan-Terry & Sanchez, 2009). Workforce Preparation and Citizenship Development Citizenship is defined as the qualities that a person is expected to have as a responsible member of the community (Citizenship, 2013). Athletic programs are often labeled as counterproductive to the mission of higher education institutions because of the perceived flaws in this area, specifically due to the win-at-all-costs attitude and academic scandals portrayed in the media. Social responsibility and civic education characteristics are constantly scrutinized; however, community colleges take a different approach to the management and training of their teams and, therefore, do not often struggle with such issues. Unlike four-year athletic programs, community college sports teams are not under constant pressure to fill stadiums, generate millions in revenue, and produce professional- level athletes. While winning is always an important goal of a program and its athletes, it is not a win-at-all-cost mentality or environment. Additionally, the NJCAA, as previously mentioned, requires player academic evaluations be performed at the end of every semester, leading to greater levels of player and coaching accountability. These programs do not often participate in the recruiting of big name athletes so the need to impress, and the politics associated with such activity, is not a common issue. Community college athletic programs cater to the community. They are largely comprised of local-grown students who just want to play their desired sport for a few more years or have transfer aspirations. These programs, by nature, combat most of the negative stereotypes

SCORE OR PENALTY

11

often associated to collegiate programs and portray the heart and value of athletics: exposure to working in an ethnic, racial, cultural, and age diverse environment, time management, accountability, integrity, mentorship, networking, volunteerism, and teamwork, especially in adverse situations. These are among the citizenship characteristics instilled, enhanced, and offered in community college athletic programs and are indispensible qualities needed for students future business endeavors and workplace success. Summary Community colleges play a critical role in the American higher education system. They offer their surrounding communities educational and co-curricular resources and activities at a fraction of the cost of most four-year institutions. In the wake of the demand for a skilled, educated workforce, these institutions are taxed with preparing and fixing the labor force and economy while still giving the students the four-year experience many of them desire. Athletic programs are just one way these institutions can effectively, and holistically, address this demand from both the employers and the students. They equip and assist many students with the academic support as well as the personal and professional development needed to obtain successful work placement after graduation. There is little research done on community college athletic programs and their benefits on students and the community. This is problematic in the wake of financial distress the higher education system is faced with as colleges and universities are looking for programs to cut, however, by these programs offering the magnitude of resources to their student population, as well as the benefits they bring to their local communities, a strong argument can be made in support of the belief community college athletics compliment the mission and objectives the individual institutions, the community college structure, and higher education as a whole.

SCORE OR PENALTY References

12

Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25, 297-308. Astin, A. W. (1993a). Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and practice of assessment and evaluation in higher education (p.18). Phoenix: The Oryx Press. Astin, A. W. (1993b). What matters in college: Four critical years revisited. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Ashburn, E. (2007). To increase enrollment, community colleges add more sports. Education Digest, 73, 58-60. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=aph& AN=27177343&site=ehost-live Bush, V., Castaneda, C., Hardy, D. E., & Katsinas, S. G. (2009). What the numbers say about community colleges and athletics. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2009, 5-14. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db= aph&AN =44338786&site=ehost-live California Community College Athletics Association (2012). About the CCCAA. Retrieved from http://www.cccaasports.org/COA.pdf Champion, W. J. (1990). The national junior college athletic association: A study in organizational accountability. Community College Review, 17, 47. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=9609041961&site =ehost-live Citizenship. (2013). In Merriam-Webster.com . (11th ed). Retrieved November 11, 2013, from from http://www. merriam-webster.com/dictionary/citizenship

SCORE OR PENALTY

13

Gayles, J. G. & Rockenbach, A. B. & Davis, H. A.(2012). Civic Responsibility and the Student Athlete: Validating a New Conceptual Model. The Journal of Higher Education 83, 535-557. The Ohio State University Press. Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ journal_of_higher_education/v083/83.4.gayles.html Hajart, A.F., Toscano, L., Horsley, K., & Del Re, L.M. (2007). Function, Benefits, and Development of Athletic Training Student Organizations. Athletic Therapy Today, 12, 21-34. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h& AN=23779158&site=ehost-live Hanks, M. P., & Eckland, B. K., (Oct., 1976). Athletics and social participation in the educational attainment process. Sociology of Education, 49, 271-294. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2112314 Lawrence, H. J., Mullin, C. M., & Horton Jr., D. (2009). Considerations for expanding, eliminating, and maintaining community college athletic teams and programs. New Directions For Community Colleges, 2009, 39-51. Retrieved from http://search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=44338783&site=ehost-live National Junior College Athletic Association (2013). NJCAA Forms. Retrieved from http://www.njcaa.org/njcaaforms/130528_2_Prospective%20student%20brochure%201 3-14.pdf Noonan-Terry, C. M., & Sanchez, R. M. (2009). Honing athletic skills, academics at community colleges. Diverse: Issues In Higher Education, 26, 20. Retrieved from http://search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=41035881&site=ehost-live

SCORE OR PENALTY

14

Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges (2013a). 2012-2013 Annual Report. Retrieved from http://www.nwaacc.org/marketing/annual_reports/2012-13_NWAACC _Annual_ Report.pdf Northwest Athletic Association of Community Colleges (2013b). About Us. Retrieved from http://www.nwaacc.org/aboutus.php Schneder, R., & Messenger, S. (2012). The impact of athletic facilities on the recruitment of potential student-athletes. College Student Journal, 46, 805-81. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=84271977&site=e host-live Storch, J., & Ohlson, M. (2009). Student services and student athletes in community colleges. New Directions For Community Colleges, 2009, 75-84. Retrieved from http://search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=44338780&site=ehost-live Teague, M. (2012). Rising from the ashes; strong leadership lifts the NJCAA to prominence after WWII. NJCAA Review, 64, 5-7. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com /login.aspx?direct= true&db=s3h&AN=82901031&site=ehost-live FAQs on community engagement. (2007). NCAA News, 44, 17. Retrieved from http://search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&AN=24345397&site=ehost-live

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Athletics in The American Community CollegeDocument12 paginiAthletics in The American Community Collegeapi-251589938100% (1)

- Chapter 2Document17 paginiChapter 2Jonathan AlugÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carlson On Athletic IQDocument2 paginiCarlson On Athletic IQJohn O. HarneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- pr2 1Document30 paginipr2 1Julius Arthur Reformina OlacoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Document6 pagini2api-643594407Încă nu există evaluări

- ResearchDocument2 paginiResearchMaria Ericka Gayban RomeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Document7 pagini2api-643594407Încă nu există evaluări

- JIIA 2014 7 20 Athletes Perceptions 410 430Document21 paginiJIIA 2014 7 20 Athletes Perceptions 410 430krizza urmazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revealing The Lived Experiences of Senior High School Students in Balancing Athletic Activities and Academic PerformanceDocument32 paginiRevealing The Lived Experiences of Senior High School Students in Balancing Athletic Activities and Academic PerformancemoskovbringerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epsa FinalDocument31 paginiEpsa Finalapi-443038453Încă nu există evaluări

- A Study On SixtyDocument4 paginiA Study On SixtyTrisha AnneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Current Status of Sports FacilitiesDocument5 paginiCurrent Status of Sports FacilitiesMike Gonzales JulianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Are Student Athletes Funding Your Future?: No More Excuses: Pay Me!De la EverandWhy Are Student Athletes Funding Your Future?: No More Excuses: Pay Me!Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Formative Evaluation Plan Alyssa Avila Kan Li Cris Monroy Pam NewtonDocument48 paginiFinal Formative Evaluation Plan Alyssa Avila Kan Li Cris Monroy Pam Newtonapi-318952018Încă nu există evaluări

- Choice Factors and Best Fit Principles Encouraging "Best Fit" Principles: Investigating College Choice Factors of Student-Athletes in NCAA Division I, II, and III Men's WrestlingDocument15 paginiChoice Factors and Best Fit Principles Encouraging "Best Fit" Principles: Investigating College Choice Factors of Student-Athletes in NCAA Division I, II, and III Men's WrestlingJournal of Theories and Application The International EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Assistance For Varsity Students of Pasig Catholic College: A Basis For Creating Monthly Allowance Proposal For AthletesDocument26 paginiFinancial Assistance For Varsity Students of Pasig Catholic College: A Basis For Creating Monthly Allowance Proposal For AthletesElizar Vince CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Student Athlete ExperienceDocument9 paginiThe Student Athlete ExperienceAyman The Ez GamerÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Retrospective Evaluation of Interscholastic Athletic Program of A State University in The PhilippinesDocument6 paginiA Retrospective Evaluation of Interscholastic Athletic Program of A State University in The PhilippinesDan RogayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- College Choice Factors For Division I AthletesDocument11 paginiCollege Choice Factors For Division I AthletesOmen OdinsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Argumentative EssayDocument11 paginiArgumentative EssayJhon Mark Miranda SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- B1G Statement On GovernanceDocument4 paginiB1G Statement On GovernanceScott DochtermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- FulltextDocument42 paginiFulltextkuirt miguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- StudentAffairsAnnualReport 2016 FinalForWebDocument23 paginiStudentAffairsAnnualReport 2016 FinalForWebtdfield100% (1)

- Individual and Institutional Challenges Facing Student Athletes oDocument10 paginiIndividual and Institutional Challenges Facing Student Athletes oPhilip ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exploring How Student Athletes Balance Athletic Academic and Personal Needs. PDFDocument35 paginiExploring How Student Athletes Balance Athletic Academic and Personal Needs. PDFVeluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shape of The Nation 2016 ReportDocument142 paginiShape of The Nation 2016 ReportMinnesota Public RadioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Purpose Development For Athletic Programs: Building World Class Athletic Programs Through A World Class CharacterDocument9 paginiPurpose Development For Athletic Programs: Building World Class Athletic Programs Through A World Class Characterapi-202868199Încă nu există evaluări

- Wvu Athletic Training CourseworkDocument7 paginiWvu Athletic Training Courseworkafiwfnofb100% (2)

- HottopicDocument7 paginiHottopicapi-487900902Încă nu există evaluări

- Involvement in Mckinney Isd Athletics Benefits Student Athletes AcademicallyDocument3 paginiInvolvement in Mckinney Isd Athletics Benefits Student Athletes Academicallyapi-234155284Încă nu există evaluări

- Bestpractices FinalDocument8 paginiBestpractices Finalapi-278405894Încă nu există evaluări

- The Effective Performance Plan: A Strategic Sports-Based Childhood Obesity and Juvenile Delinquency Prevention Pipeline Program - New York StateDocument28 paginiThe Effective Performance Plan: A Strategic Sports-Based Childhood Obesity and Juvenile Delinquency Prevention Pipeline Program - New York StatechonbenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analyzing Ethics in The Administration of Interscholastic SportsDocument24 paginiAnalyzing Ethics in The Administration of Interscholastic Sportsapi-242922052Încă nu există evaluări

- Extension Program For Sports and Physical Developmentin Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in Zambales, Philippines:Appraised Participation and BenefitsDocument11 paginiExtension Program For Sports and Physical Developmentin Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in Zambales, Philippines:Appraised Participation and BenefitsAJHSSR JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- INTRODUCTION WPS OfficeDocument10 paginiINTRODUCTION WPS OfficeMichael JumawidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 paginiUntitled DocumentJMCCONISPOWELLSTUÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sports Crazy: How Sports Are Sabotaging American SchoolsDe la EverandSports Crazy: How Sports Are Sabotaging American SchoolsÎncă nu există evaluări

- BalancingDocument38 paginiBalancingNorman AntonioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Running Head: Office For Post-Eligible Athletes 1Document17 paginiRunning Head: Office For Post-Eligible Athletes 1api-299755224Încă nu există evaluări

- PSU AFC Report FinalDocument15 paginiPSU AFC Report FinalMatt BrownÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ncaa 1Document17 paginiNcaa 1api-519917908Încă nu există evaluări

- NCCADocument7 paginiNCCAZC47Încă nu există evaluări

- Better Fencer Guide NCAA FencingDocument59 paginiBetter Fencer Guide NCAA FencingDaniel Gonçalves100% (1)

- Business Plan For YnaDocument12 paginiBusiness Plan For Ynaapi-249853964Încă nu există evaluări

- PHD Thesis in Physical Education in IndiaDocument6 paginiPHD Thesis in Physical Education in Indialjctxlgld100% (2)

- Financial InequalitiesDocument1 paginăFinancial InequalitiescoachjbetzÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sport of School: Help Your Student-Athlete Win in the ClassroomDe la EverandThe Sport of School: Help Your Student-Athlete Win in the ClassroomÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Students ParticipationDocument19 paginiThe Effects of Students ParticipationMary Marmeld UdaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sports Practical Research 2Document11 paginiSports Practical Research 2Laurence Anthony MercadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrity in SportDocument4 paginiIntegrity in SportGoutaman_rÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adams, Sean, CapstoneDocument13 paginiAdams, Sean, Capstoneapi-282985696Încă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of A Campus Service Quality RecreationaDocument16 paginiEvaluation of A Campus Service Quality RecreationabenitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2Document9 paginiChapter 2Jerome EncinaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- ResearchDocument4 paginiResearchZharien VitangcolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lessons From The NFL For Managing College EnrollmentDocument31 paginiLessons From The NFL For Managing College EnrollmentCenter for American ProgressÎncă nu există evaluări

- For Weebly Student Development Student Athletes GradedDocument17 paginiFor Weebly Student Development Student Athletes Gradedapi-338016745Încă nu există evaluări

- Inbound 4182457335031704333Document3 paginiInbound 4182457335031704333Niña ChanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amherst College Athletics ReportDocument35 paginiAmherst College Athletics ReportledermandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Chapter 2Document9 paginiFinal Chapter 2Jerome EncinaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Serological and Molecular DiagnosisDocument9 paginiSerological and Molecular DiagnosisPAIRAT, Ella Joy M.Încă nu există evaluări

- Yukot,+houkelin 2505 11892735 Final+Paper+Group+41Document17 paginiYukot,+houkelin 2505 11892735 Final+Paper+Group+410191720003 ELIAS ANTONIO BELLO LEON ESTUDIANTE ACTIVOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daud Kamal and Taufiq Rafaqat PoemsDocument9 paginiDaud Kamal and Taufiq Rafaqat PoemsFatima Ismaeel33% (3)

- Insomnii, Hipersomnii, ParasomniiDocument26 paginiInsomnii, Hipersomnii, ParasomniiSorina TatuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hedonic Calculus Essay - Year 9 EthicsDocument3 paginiHedonic Calculus Essay - Year 9 EthicsEllie CarterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anindya Anticipatory BailDocument9 paginiAnindya Anticipatory BailYedlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AdverbsDocument10 paginiAdverbsKarina Ponce RiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Report - Solving Traveling Salesman Problem by Dynamic Programming Approach in Java Program Aditya Nugroho Ht083276eDocument15 paginiFinal Report - Solving Traveling Salesman Problem by Dynamic Programming Approach in Java Program Aditya Nugroho Ht083276eAytida Ohorgun100% (5)

- Butterfly Valve Info PDFDocument14 paginiButterfly Valve Info PDFCS100% (1)

- Quarter 3 Week 6Document4 paginiQuarter 3 Week 6Ivy Joy San PedroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bfhi Poster A2Document1 paginăBfhi Poster A2api-423864945Încă nu există evaluări

- Business Finance and The SMEsDocument6 paginiBusiness Finance and The SMEstcandelarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise No.2Document4 paginiExercise No.2Jeane Mae BooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Star QuizDocument3 paginiStar Quizapi-254428474Încă nu există evaluări

- Maths Lowersixth ExamsDocument2 paginiMaths Lowersixth ExamsAlphonsius WongÎncă nu există evaluări

- CU 8. Johnsons Roy NeumanDocument41 paginiCU 8. Johnsons Roy NeumanPatrick MatubayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Computer Application in Chemical EngineeringDocument4 paginiComputer Application in Chemical EngineeringRonel MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Recipe For Oleander Sou1Document4 paginiThe Recipe For Oleander Sou1Anthony SullivanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trump's Fake ElectorsDocument10 paginiTrump's Fake ElectorssiesmannÎncă nu există evaluări

- 221-240 - PMP BankDocument4 pagini221-240 - PMP BankAdetula Bamidele OpeyemiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11Document12 paginiMezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11riftÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quarter: FIRST Week: 2: Ballecer ST., Central Signal, Taguig CityDocument2 paginiQuarter: FIRST Week: 2: Ballecer ST., Central Signal, Taguig CityIRIS JEAN BRIAGASÎncă nu există evaluări

- #6 Decision Control InstructionDocument9 pagini#6 Decision Control InstructionTimothy King LincolnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sukhtankar Vaishnav Corruption IPF - Full PDFDocument79 paginiSukhtankar Vaishnav Corruption IPF - Full PDFNikita anandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lewin's Change ManagementDocument5 paginiLewin's Change ManagementutsavÎncă nu există evaluări

- UT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Document1 paginăUT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Atharv KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simulation of Channel Estimation and Equalization For WiMAX PHY Layer in Simulink PDFDocument6 paginiSimulation of Channel Estimation and Equalization For WiMAX PHY Layer in Simulink PDFayadmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 6Document15 paginiMathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 6Ray Phillip G. Jorduela0% (1)

- Conrail Case QuestionsDocument1 paginăConrail Case QuestionsPiraterija100% (1)

- Hce ReviewerDocument270 paginiHce ReviewerRaquel MonsalveÎncă nu există evaluări