Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

RCL Rhetorical Analysis

Încărcat de

api-252811580Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

RCL Rhetorical Analysis

Încărcat de

api-252811580Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Brandon McCormick Dr. Lyn J.

Freymiller CAS 137H 25 September 2013 A Rhetorical Analysis of The Perils of Indifference In a way, to be indifferent to that suffering is what makes the human being inhuman. This is a point that is asserted in a speech by Eliezer Elie Wiesel on April 12, 1999. The speech was part of the White House Millennium Lecture Series that was hosted by President Bill Clinton and the First Lady Hillary Clinton, and was delivered in the presence of the President, the First Lady, and over 200 dignitaries. It was also broadcast on international television. This speech is rhetorically fascinating as it tries to deliver its message to millions of people from different countries, cultures, and backgrounds and does so in an effective way. Because of this, the piece warrants an extensive rhetorical analysis for the aforementioned reason, but also because it was written and delivered by one of the foremost experts on the Holocaust and moral issues. Elie Wiesel has looked evil in the eye and now speaks with great eloquence from his vast personal experience. This analysis will break down the argument asserted by Wiesel into the three basic proofs: ethos, logos, and pathos. Included in his ethical appeal, I will explore Wiesels kairos or timing. I will also include some thoughts on the brief introduction given by Hillary Clinton in this analysis, as it gives an important preface to the speech that works as part of the ethical appeal. These appeals work in conjunction to effectively relay his message so that his audience will take note of what he is saying and be wary of the perils of indifference in the future. Also, I will look at the opinions of others who have analyzed the speech.

Ethical Appeal, Including Kairotic Elements Elie Wiesel is recognized as one of the foremost experts on the Holocaust. As Alexandra Glynn writes in her analysis of the speech, He is also a kind of public person who speaks with moral authority on moral issues.(Elie Wiesel's 'Perils of Indifference' and the Ownership of Words, Ideographs, and Archetypal Metaphors). Glynn is referencing the credibility that Wiesel had before he even began to speak. This comes from Wiesels status as an expert on the topic. The audience becomes aware of this expertise through the introduction delivered by Hillary Clinton. Wiesel has written over 40 books, including his publication for which he his most widely known, Night. Because of his writings, he is considered to be one of the most important writers on the Holocaust. He was also awarded with the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Congressional Gold Medal. Wiesel also served as Chairman for the Presidential Commission on the Holocaust and led the effort to create the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. This means that members of the audience, who were not familiar with Wiesels life experiences, were now informed because of the introduction, and by knowledge that much of his audience had before his presentation. Wiesel is recognized as an expert on the topic, which provides him with the ethos that he needs to effectively deliver his message on indifference. Wiesel knew of the introduction before he delivered the speech and effectively utilized it; thus allowing him to spend the majority of his speech delivering his message, not worrying about his credibility that was already established by the introduction, and by the audiences prior knowledge. Wiesel does, however, take some time during his speech to establish credibility on his own. Much of Wiesels credibility comes from his experiences during the Holocaust, as he was imprisoned in the Auschwitz concentration camp where he was forced to work at a rubber plant.

He also spent time in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Wiesel speaks directly of his experience in the speech stating, Over there, behind the black gates of Auschwitz, the most tragic of prisoners were the Muselmanner. They no longer felt pain, hunger, thirst. They feared nothing. They felt nothing. They were dead and did not know it (White House Millennium Lecture series - #7). In this quotation and in others, Wiesel refers to his personal experience as a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp. This helps to establish his credibility by relaying to the audience that he experienced the product of widespread indifference first hand. The indifference did not come at the hands of the Nazis (but by those German citizens who saw what was happening and did nothing, and by the world at large including the United States). However the establishment of Wiesels ethos goes far beyond the content of his speech. Also, the kairos, or timing of the speech is all but perfect. Wiesels speech is delivered on the coattails of the ethnic genocide that was perpetrated in the former Yugoslavia. At the time of the speechs delivery, the matter of genocide is fresh in peoples minds, and they are asking themselves How did this happen? and How can we prevent this from happening again? Both of these questions are addressed in the speech (I will go into details on how Wiesel answers these questions in my analysis of his logical appeal). The speaker makes multiple references to the most recent genocide. In other words, Wiesel knew to strike while the iron was hot. After Wiesels ethos was established, he could move on to the body of his argument and to get to the purpose of his speech to develop his logical appeal or logos. Logical Appeal Wiesel organizes his speech in a very deliberate and effective way. In his essay on the speech, Eric Bressman writes, Essentially, his question raises two separate but equally important issues: What motivates indifference, and what are its consequences?(Fighting

Indifference: Looking at World Response to the Holocaust with Elie Wiesel). This does not go far enough. The two questions match those found in Wiesels appeal, but Bressman neglects to mention an important third part, in which Wiesel expresses hope to a brighter future, in which people take action when tempted with indifference. To begin his logical appeal, Wiesel defines what indifference is. He first gives the etymological definition of indifference, but then goes on and gives a different definition of indifference what it means to him and how it relates to the issue at hand. This step in his logical argument proposes what indifference means; as Wiesel puts it is, A strange and unnatural state in which the lines blur between light and darkness This definition serves as a base for the rest of his appeal. After proposing the definition, he them moves on to assert that indifference can be tempting more than that, seductive, but warns of the consequences if one goes this path In the next portion of his appeal, Wiesel says, It is so much easier to look away from victims. It is so much easier to avoid such rude interruptions to our work, our dreams, our hopes. By this, Wiesel means that it is far easier to take the path of indifference and inaction to continue our everyday routine, without allowing such interruptions as the plight of others to interfere. Wiesel then reminds the audience of the consequences of peoples past indifference. He does this by speaking about some of his personal experiences in the Nazi extermination camp Auschwitz. At this point the audience, mostly made up of Americans, may see the issue of the Holocaust as the result of European indifference, an issue far removed from the United States. Wiesel brings the issue home, so to speak, by first asserting the argument that many Americans hold and use to relieve them of guilt. That is, if the United States government knew of the Holocaust, they surely would have acted. He then attacks this argument by saying that in fact the Government of the United States of America was aware of the atrocities being

committed across the Atlantic. Wiesel says, And now we knew, we learned, we discovered that the Pentagon knew, the State Department knew. He then continues to assert that even Franklin Roosevelt knew. Wiesel does not demean the former president though; he refers to FDR as a good man, who fell victim to indifference. Still, some in the audience may say that there was nothing the government could do, as they were thousands of miles away. Wiesel strikes down this argument by telling the story of the ship, the St. Louis, a ship full of Jewish refugees that were seeking refuge in the United States. The U.S. Government had the opportunity to save a thousand people, yet they still turned them away. The government was indifferent to the plight of the refugees. Wiesel speaks to the seductiveness of indifference, due to the tendency for people to desperately cling to their routines; then he shows the consequences of indifference by using an example that a largely American audience can identify with and cannot refute. In her essay on the topic of indifference, Kathleen Barry agrees with this interpretation of Wiesels logical appeal. She writes, This rhetorical situation matures and persists because Wiesel relates the past to a current situation, (Indifference Has No Justification in the 21st Century: A Critical Analysis of Elie Wiesels "The Perils of Indifference). But his logical appeal does not end there; he completes it by offering a message of hope. Wiesel begins his message of hope by saying, And then, of course, the joint decision of the United States and NATO to intervene in Kosovo and save those victims, those refugees, those who were uprooted by a man whom I believe that because of his crimes, should be charged with crimes against humanity. But this time, the world was not silent. This time, we do respond. This time we intervene.

In this statement, Wiesel is speaking to the recent incident of ethnic genocide in the former Yugoslavia. It was perpetrated primary by Slobodan Miloevi, who is the man referenced in the quote. The joint decision that Wiesel mentions is the decision by the United States and NATO to aid the Kosovo Liberation Army with air support. This example shows signs of improvement and reasons for the audience to look towards the future with hope. The intervention in Kosovo works in stark contrast with the indifferent attitude that was dominant during the Holocaust. This contrast shows that Americans can counteract indifference through action and that this action will have positive consequences. This final hopeful section of his logos will, hopefully, cause action in the future. This brings up the third appeal that Wiesel uses to make his speech more effective, and that is pathos, or emotions. Pathetic Appeal In much of his speech, Wiesel uses emotional subjects and language. These are most evident in the beginning and in the end of his speech. He begins the speech by telling a story of a young boy who was just liberated from Buchenwald and had no joy in his heart. At the end of his speech, Wiesel brings this full circle by revealing that the little boy was, in fact, himself. This anecdote makes effective use of pathos by making the audience picture a victim of indifference, which is made even more effective because that victim is standing before them. In another section of the speech, the speaker asks the audience how they want to be remembered. He says, We are on the threshold of a new century, a new millennium. What will the legacy of this vanishing century be? How will it be remembered in the new millennium? In this statement, Wiesel is asking the audience about their legacy; by doing this, he is evoking deep-seeded emotions in the audience. He is telling them that they have a choice to make, and

the option they choose will become part of their legacy as a generation. No one wants to be remembered as the generation that failed to act, the generation that was indifferent. Arguably, the most emotional portion of the speech is Wiesels final words, his final call to action. Where he says, What about the children? ... Do we hear their pleas? Do we feel their pain, their agony? Every minute one of them dies of disease, violence, famine. Some of them so many of them could have been saved. In this statement, Wiesel speaks of a very emotional topic, the death of children, and uses it to remind the audience of the innocent victims of indifference. This appeal is extremely effective as it gains the attention of the audience, and will ultimately make them more likely to act in the future. Conclusion In his speech on The Perils of Indifference, delivered at the White House, Elie Wiesel addressed an issue that holds relevant to this day. That is, what the consequences are if people choose to be indifferent to the plight of others around the world. In his speech, Wiesel made effective use of rhetorical appeals including ethos, logos, and pathos. Equally important, he also employed kairos. He did this by delivering his speech at a time when the choice between indifference and action could mean the loss or salvation of millions of people. Wiesels speech on indifference provides a powerful lesson that is vital to the well-being of the human race as we forge on into the future. This lesson that Wiesel puts forth can be summarized in this statement, given at a different time by Wiesel, The opposite of love is not hate, it's indifference. The opposite of beauty is not ugliness it's indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy it's indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, but indifference between life and death.

Works Cited Barry, Kathleen. "Indifference Has No Justification in the 21st Century: A Critical Analysis of Elie Wiesels "The Perils of Indifference"" Wordpress.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2013. Bressman, Eric. "Fighting Indifference: Looking at World Response to the Holocaust with Elie Wiesel." The Morningside Review. Columbia University, n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2013. Glynn, Alexandra. "Elie Wiesel's 'Perils of Indifference' and the Ownership of Words, Ideographs, and Archetypal Metaphors." Social Science Research Network.com. North Dakota State University, 11 Dec. 2010. Web. 24 Sept. 2013. White House Millennium Lecture Series - #7. Perf. Hillary Clinton and Elie Wiesel. YouTube. The Clinton Library, 25 Apr. 2012. Web. 30 Sept. 2013.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Essay Elie WieselDocument3 paginiEssay Elie WieselZedan HejaziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Four Hasidic Masters and Their Struggle against MelancholyDe la EverandFour Hasidic Masters and Their Struggle against MelancholyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (4)

- Final Draft Perils of Indifference e ChristodossDocument5 paginiFinal Draft Perils of Indifference e Christodossapi-356975105Încă nu există evaluări

- Summary and Analysis of Night: Based on the Book by Elie WieselDe la EverandSummary and Analysis of Night: Based on the Book by Elie WieselÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay 2Document5 paginiRhetorical Analysis Essay 2api-511875808Încă nu există evaluări

- Planet Auschwitz: Holocaust Representation in Science Fiction and Horror Film and TelevisionDe la EverandPlanet Auschwitz: Holocaust Representation in Science Fiction and Horror Film and TelevisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 paginiUntitled Documentapi-359544595Încă nu există evaluări

- Elie Wiesel SpeechDocument3 paginiElie Wiesel Speechapi-643511800Încă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement Night Elie WieselDocument4 paginiThesis Statement Night Elie Wieselheatherharveyanchorage100% (2)

- Kristina Ellis Speech AnalysisDocument3 paginiKristina Ellis Speech Analysisapi-311546428Încă nu există evaluări

- Night Essay Elie WieselDocument6 paginiNight Essay Elie WieselFrancesca Elizabeth100% (1)

- Speech CritiqueDocument4 paginiSpeech CritiqueThomas ElliottÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Draft 3Document4 paginiFinal Draft 3api-483699566Încă nu există evaluări

- Night Elie Wiesel ThesisDocument4 paginiNight Elie Wiesel Thesisaflodnyqkefbbm100% (2)

- Night Study & Essay QsDocument2 paginiNight Study & Essay QsKelley Esham Bentley50% (2)

- The Silent ChoiceDocument31 paginiThe Silent ChoiceThomas WhitleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Temas para El Ensayo de La Noche de Elie WieselDocument7 paginiTemas para El Ensayo de La Noche de Elie Wieselhxvgtlwlf100% (1)

- Research Paper Topics For Night by Elie WieselDocument6 paginiResearch Paper Topics For Night by Elie Wieselaflbvmogk100% (1)

- Thesis Statement For The Book Night by Elie WieselDocument8 paginiThesis Statement For The Book Night by Elie Wieselgjcezfg9100% (2)

- EssayDocument3 paginiEssayapi-273536087Încă nu există evaluări

- Night Elie Wiesel Essay Thesis StatementDocument4 paginiNight Elie Wiesel Essay Thesis Statementveronicaperezvirginiabeach100% (2)

- Grünberg2007 Article ContaminatedGenerativityHolocaDocument15 paginiGrünberg2007 Article ContaminatedGenerativityHolocaSiscu Livesin DetroitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Night Thesis Statements Elie WieselDocument4 paginiNight Thesis Statements Elie Wieselkarenstocktontulsa100% (2)

- The Perils of Indifference AnalysisDocument4 paginiThe Perils of Indifference Analysisapi-582846094100% (1)

- Cia 4 SpeechanalysisDocument2 paginiCia 4 Speechanalysisapi-319248902Încă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement Faith Night Elie WieselDocument6 paginiThesis Statement Faith Night Elie Wieselowynqovcf100% (1)

- Loss of Faith in "Night" We Are The Result of All The Experiences and Memories We Have (Argumentative Essay)Document7 paginiLoss of Faith in "Night" We Are The Result of All The Experiences and Memories We Have (Argumentative Essay)miguel angel vasquez martinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1Document50 paginiChapter 1Seemant SinglaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indifference EssayDocument5 paginiIndifference Essayapi-698788059Încă nu există evaluări

- Night Teachers GuideDocument8 paginiNight Teachers GuideJake CabatinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Night by Elie Wiesel Essay ThesisDocument7 paginiNight by Elie Wiesel Essay Thesisevelyndonaldsonbridgeport100% (1)

- Night Elie Wiesel Thesis StatementDocument4 paginiNight Elie Wiesel Thesis Statementjessicamoorereno100% (2)

- The Holocaust - Interesting ArithmeticDocument5 paginiThe Holocaust - Interesting ArithmeticHuckelberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- AlbertraezDocument5 paginiAlbertraezapi-305647212Încă nu există evaluări

- Elie Wiesel Night Research PaperDocument5 paginiElie Wiesel Night Research Paperfvgcaatd100% (1)

- The Perils of IndifferenceDocument3 paginiThe Perils of IndifferencegabyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper Night Elie WieselDocument5 paginiResearch Paper Night Elie Wieseltutozew1h1g2Încă nu există evaluări

- Elie Wiesel Night Research Paper TopicsDocument7 paginiElie Wiesel Night Research Paper Topicsaflefvsva100% (1)

- Some Interesting ArithmeticDocument4 paginiSome Interesting ArithmeticHuckelberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Night ResponseDocument3 paginiNight Responseapi-319574735Încă nu există evaluări

- Woodrow Wilson, FreudDocument23 paginiWoodrow Wilson, FreudMichael H. HejaziÎncă nu există evaluări

- KnightDocument4 paginiKnightapi-386509811Încă nu există evaluări

- Night EssayDocument4 paginiNight Essayapi-386184718Încă nu există evaluări

- Creative Title For Holocaust Research PaperDocument6 paginiCreative Title For Holocaust Research Papergw2cy6nx100% (1)

- NightDocument8 paginiNightAnzhar TadjaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decision-Making in Times of Injustice Lesson 15Document28 paginiDecision-Making in Times of Injustice Lesson 15Facing History and OurselvesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hatred and HumanityDocument6 paginiHatred and HumanityDude ThatÎncă nu există evaluări

- NightessayDocument3 paginiNightessayapi-295946653Încă nu există evaluări

- Pillar of Caste EssayDocument4 paginiPillar of Caste EssayElahehNasrin KarimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement Examples For Night by Elie WieselDocument7 paginiThesis Statement Examples For Night by Elie Wieselbellabellmanchester100% (2)

- The Universalist HolocaustDocument5 paginiThe Universalist HolocaustVienna1683Încă nu există evaluări

- How To Write A Thesis Statement About The HolocaustDocument8 paginiHow To Write A Thesis Statement About The Holocaustashleyjonesmobile100% (2)

- Elie Wiesel Nobel SpeechDocument6 paginiElie Wiesel Nobel Speechapi-294659520Încă nu există evaluări

- Story and Silence: Transcendence in The Work of Elie Wiesel: Gary HenryDocument17 paginiStory and Silence: Transcendence in The Work of Elie Wiesel: Gary HenryBoris MakaverÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - W. James Booth 2011Document15 pagini1 - W. James Booth 2011Raquel RochaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Criticism - NightDocument3 paginiLiterary Criticism - NightAisling MurphyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meet Elie WieselDocument3 paginiMeet Elie Wieselapi-295190740Încă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Ideas For Night by Elie WieselDocument7 paginiThesis Ideas For Night by Elie Wieselbrendawhitejackson100% (2)

- CV BrandonmccormickDocument4 paginiCV Brandonmccormickapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- B-Palmer NoteDocument7 paginiB-Palmer Noteapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Psych490 FinalpaperDocument30 paginiPsych490 Finalpaperapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Brandon Activity6Document1 paginăBrandon Activity6api-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Brandonmccormick ResumeDocument2 paginiBrandonmccormick Resumeapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Crim430 FinalpaperDocument22 paginiCrim430 Finalpaperapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Psych445 FinalpaperDocument14 paginiPsych445 Finalpaperapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Running Head: An Analysis of Clinical Pyromania 1Document9 paginiRunning Head: An Analysis of Clinical Pyromania 1api-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Egee Semester PaperDocument14 paginiEgee Semester Paperapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Egee Reflective Essay 2Document6 paginiEgee Reflective Essay 2api-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Egee Final EssayDocument2 paginiEgee Final Essayapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Egee Reflective EssayDocument4 paginiEgee Reflective Essayapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- RCL Ted Talk PresentationDocument6 paginiRCL Ted Talk Presentationapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- RCL Paradigm Shift EssayDocument11 paginiRCL Paradigm Shift Essayapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- RCL Persuasive EssayDocument12 paginiRCL Persuasive Essayapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Brandon F. Mccormick: EducationDocument1 paginăBrandon F. Mccormick: Educationapi-252811580Încă nu există evaluări

- Kairós. Towards An Ontology of 'Due Time' - Giácomo Marramao (Resenha de Andrew Baird)Document9 paginiKairós. Towards An Ontology of 'Due Time' - Giácomo Marramao (Resenha de Andrew Baird)Edmar Victor Guarani-Kaiowá Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Neo-Aristotelian Analysis: Churchill's "Be Ye Men of Valour"Document22 paginiNeo-Aristotelian Analysis: Churchill's "Be Ye Men of Valour"Krista Bornman50% (2)

- Rhetorical Triangle PDFDocument1 paginăRhetorical Triangle PDFapi-322718373Încă nu există evaluări

- Chronos and Kairos - Patrick Reardon PDFDocument2 paginiChronos and Kairos - Patrick Reardon PDFVasile AlupeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Momo ProgrammeDocument20 paginiMomo Programmeaidan.sarsozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kairos and The Rhetorical SituationDocument17 paginiKairos and The Rhetorical Situations_rank90Încă nu există evaluări

- Seize Your Kairos Moment - Mensa OtabilDocument25 paginiSeize Your Kairos Moment - Mensa OtabilFred Raphael Ilomo100% (1)

- Rhetorical AnalysisDocument6 paginiRhetorical Analysisapi-485256044Încă nu există evaluări

- Eng 105 ReflectionDocument7 paginiEng 105 Reflectionapi-438108410Încă nu există evaluări

- Kairoticism: The Transcendentals of RevolutionDocument61 paginiKairoticism: The Transcendentals of RevolutionRowan G TepperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 7 HandoutDocument6 paginiLecture 7 HandoutlesanglaisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engagements With Rhetoric A Path To Academic WritingDocument417 paginiEngagements With Rhetoric A Path To Academic WritingTravis Jeffery100% (1)

- Essay 2 - Lyric Analysis - Assignment InstructionsDocument2 paginiEssay 2 - Lyric Analysis - Assignment InstructionsPaul WorleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- God39s Kairos MomentDocument3 paginiGod39s Kairos MomentAaronÎncă nu există evaluări

- February 15Document3 paginiFebruary 15api-548610645Încă nu există evaluări

- Tactical Research: Practices For Thinking (Oneself) Differently Emma CockerDocument10 paginiTactical Research: Practices For Thinking (Oneself) Differently Emma CockeremmacockerÎncă nu există evaluări

- William FaulknerDocument5 paginiWilliam Faulknerapi-285149799Încă nu există evaluări

- 10 Understanding Spiritual Times and Seasons - Apostle Philip CephasDocument34 pagini10 Understanding Spiritual Times and Seasons - Apostle Philip CephasApostle Philip CephasÎncă nu există evaluări

- KAIROS: Layers of MeaningDocument4 paginiKAIROS: Layers of MeaningAnonymous mNlqilGbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing Arguments A Rhetoric With Readings 10Th Edition John D Ramage All ChapterDocument67 paginiWriting Arguments A Rhetoric With Readings 10Th Edition John D Ramage All Chapterallison.nunez856100% (5)

- Mwa 2Document7 paginiMwa 2api-611190579Încă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical Analysis Final Draft - Joshua HerrinDocument4 paginiRhetorical Analysis Final Draft - Joshua Herrinapi-589103040Încă nu există evaluări

- Abolitionist Rhetoric Alyssa HendersonDocument6 paginiAbolitionist Rhetoric Alyssa Hendersonapi-438326329100% (1)

- KairosDocument3 paginiKairosBro Al Comps100% (1)

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay FinalDocument5 paginiRhetorical Analysis Essay Finalapi-356383156Încă nu există evaluări

- Metacognitive Reflection PaperDocument5 paginiMetacognitive Reflection Paperapi-273338294Încă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy For Writing Across Difference: A Coursing RiverDocument3 paginiPhilosophy For Writing Across Difference: A Coursing RiverKyra OraziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical AnalysisDocument3 paginiRhetorical Analysisapi-302467313Încă nu există evaluări

- SPACE CAT and Evidence Analysis NotetakerDocument5 paginiSPACE CAT and Evidence Analysis NotetakerRachel VincentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Response Rhetorical Strategies WorksheetDocument3 paginiCritical Response Rhetorical Strategies Worksheetapi-481110503Încă nu există evaluări

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,De la EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (69)

- Be a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooDe la EverandBe a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyDe la EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeDe la EverandThe Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesDe la EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (70)

- Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleDe la EverandSomething Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (34)

- Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyDe la EverandRiot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (13)

- The Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartDe la EverandThe Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartÎncă nu există evaluări

- When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaDe la EverandWhen and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (33)

- White Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraDe la EverandWhite Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (43)

- Shifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in AmericaDe la EverandShifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (10)

- Summary of Coleman Hughes's The End of Race PoliticsDe la EverandSummary of Coleman Hughes's The End of Race PoliticsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyDe la EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (18)

- Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and SpiritDe la EverandBlack Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and SpiritEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (83)

- Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedDe la EverandPlease Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (154)

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, 10th Anniversary EditionDe la EverandThe New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, 10th Anniversary EditionEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (1044)

- Decolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticeDe la EverandDecolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Walk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphDe la EverandWalk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (72)

- The Myth of Equality: Uncovering the Roots of Injustice and PrivilegeDe la EverandThe Myth of Equality: Uncovering the Roots of Injustice and PrivilegeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (17)

- Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American GynecologyDe la EverandMedical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American GynecologyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (75)

- Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaDe la EverandNot a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (37)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageDe la EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (82)

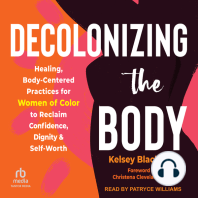

- Decolonizing the Body: Healing, Body-Centered Practices for Women of Color to Reclaim Confidence, Dignity, and Self-WorthDe la EverandDecolonizing the Body: Healing, Body-Centered Practices for Women of Color to Reclaim Confidence, Dignity, and Self-WorthEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)