Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Fridman Ra

Încărcat de

api-255704986Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Fridman Ra

Încărcat de

api-255704986Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Leonard Fridman is addressing the type of audience who reads The New York Times in

1990: educated, generally upper class citizens with the luxury of having time and opportunity to

enhance their intellectual boundaries by reading a newspaper. In this decade, celebrities like

Miley Cyrus, traumatic events such as 9/11, and technological advances like the iPhone were not

present, therefore altering the audiences perception of Fridmans writing. Through the use of

logical fallacies and tone, as well as the intentional lack of a counterargument, he develops an

argument primarily based on emotion with an appeal to pathos.

Fridman has a strong use of evidence, ranging in variety and source, that bolsters his

argument and claim that [t]here is something very wrong with the system of values in

[American] society because of our judgmental social climate. However, he does not support and

elaborate on such evidence with argumentative thoroughness, thus leaving great opportunity for

logical fallacies to deconstruct the potentially effective system of rhetoric he had built. A

primary example of the gaps in his piece is the overwhelming presence of over-generalization. In

his second paragraph, Fridman introduces the circumstances a socially restricted environment

found at Harvard University, and then ends his section with an assertion that is lacking in

support: the ostracizing of nerds and idolizing of athletes has no present or explicitly explained

correlation to the fact that most student try to keep up their grades but only a few pursue

knowledge as a top priority. Instead of assuming that nerds become social outcasts, using

a qualifier to acknowledge the opposite truth in his statement would offer a more concrete basis

for argument. Additionally, the ironic stereotypical presentation of evidence such as typical

[American parents] are ashamed of their daughter studying mathematics affords more support

for a claim against his own way of thinking than against his ideological opponent of ostracizing.

He declaratively states that nerds and geeks must stop being ashamed of who they are yet fails

in offering factual evidence of such an emotional conflict and experience of social distress.

Fridman appeals to the emotion in his audience by implicating words such as ashamed,

conformed, and ostracized to capture attention and open opportunity for empathetic

perception as well as additionally employing persuasive logical fallacies.

The efficacy of his fallacies can be analyzed by looking at the tone of his writing.

Leonard Fridman spaces these gaps in his argument evenly throughout the paper so as to not

evoke suspicion by the reader. By surrounding the fallacies with rhetorical structures of varying

sentence length and diction, he creates a setting for a persuasive tone to additionally bolster his

claim. For example, preceding the statement that nerds are ashamed at their identities, he writes,

Enough is enough, following a paragraph comprised of the persuasive yet ultimately erroneous

notion in the form of a syllogism that nerds and athletes are on opposite spectrums in the realm

of social acceptance. The brevity of this statement, Enough is enough, creates a tone of disgust

and condescension that invites the reader to ask, What is enough? and pursue their curiosity by

following the argument. Also, beginning his piece, he appeals to emotion by stating primarily

that there is something very wrong and successfully capturing attention and drawing it to the

manufactured notion that there is a significant urgency to the issue he is about to explore. More

complex sentences like those found in lines 14-17, 23-27, and 47-52 use length to draw focus

away form the detailed and unexplained content of the statement and towards the melodic

continuance of a simple point. Fridmans combination of two-word phrases such as pursuing

knowledge, our culture, and physical prowess entwine with the intent of appealing to

emotion as they act as simple identifiers of life aspects to which a majority of The New York

Times readers would be able to relate.

Finally, the lack of a counter argument shows weakness in the effectiveness of Fridmans

claim. He addresses once the concept of counterargument as he writes, Although most students

try to keep up their grades, but ultimately asserts his argument at the end of the paragraph with

an over-generalization. Tone and fallacy act as the two supporting functions of his appeal to the

motion of readers being presented with the concepts of intellectuality and its social credit and

perception. Addressing a group ofin majorityeducated status, offering the idea that nerd

may be a fitful and purposeful label for the academically inclined probably would harm his

readers rather than attract their perceptual trust. However, addressing the opposition of his

argument would afford his tone with more valid confidence and factual validity. Enhancing his

argumentative prowess quite possibly towards the end of his piece creates strength and finite

structure to his literature. Instead, Fridman offers questions and focuses on tone and how he is

influencing emotions as he concludes, which in effect is persuasive, but ultimately unstable.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and ActionDe la EverandHuman Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and ActionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- International Relations and the Challenge of Postmodernism: Defending the DisciplineDe la EverandInternational Relations and the Challenge of Postmodernism: Defending the DisciplineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fiction and the Shape of Belief: A Study of Henry Fielding with Glances at Swift, Johnson and RichardsonDe la EverandFiction and the Shape of Belief: A Study of Henry Fielding with Glances at Swift, Johnson and RichardsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Text Analysis and Evaluation Essayrevised AgainDocument6 paginiText Analysis and Evaluation Essayrevised Againapi-242283882Încă nu există evaluări

- Critical Thinking: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning ExplainedDe la EverandCritical Thinking: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning ExplainedEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (6)

- Midterm 1 Essay Response - Speiser2Document8 paginiMidterm 1 Essay Response - Speiser2Claudia MontecinosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Voices in the Wilderness: Public Discourse and the Paradox of Puritan RhetoricDe la EverandVoices in the Wilderness: Public Discourse and the Paradox of Puritan RhetoricÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Kind Word For Bullshit The Problem of AcademicDocument17 paginiA Kind Word For Bullshit The Problem of Academicanonymous42156Încă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical Analysis Final RevisedDocument6 paginiRhetorical Analysis Final Revisedapi-366055240Încă nu există evaluări

- The Rhetoric of Terror: Reflections on 9/11 and the War on TerrorDe la EverandThe Rhetoric of Terror: Reflections on 9/11 and the War on TerrorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eubanks & Schaffer (2008)Document18 paginiEubanks & Schaffer (2008)mbayanbayevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn EssayDocument4 paginiAdventures of Huckleberry Finn Essayxtnzpacaf100% (2)

- Between Peace and War: 40th Anniversary Revised EditionDe la EverandBetween Peace and War: 40th Anniversary Revised EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Challenge of Bewilderment: Understanding and Representation in James, Conrad, and FordDe la EverandThe Challenge of Bewilderment: Understanding and Representation in James, Conrad, and FordÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intellectual Entertainments: Eight Dialogues on Mind, Consciousness and ThoughtDe la EverandIntellectual Entertainments: Eight Dialogues on Mind, Consciousness and ThoughtÎncă nu există evaluări

- IntellectualismDocument4 paginiIntellectualismapi-2412340660% (1)

- Constructing The Humor AssignmentDocument10 paginiConstructing The Humor Assignmentmeetkrutik942Încă nu există evaluări

- Anti Intellectualism Why We Hate The Smart Kids EvaluationDocument4 paginiAnti Intellectualism Why We Hate The Smart Kids EvaluationTaylor Olson0% (1)

- Why Academics Stink at WritingDocument16 paginiWhy Academics Stink at WritingSaurabh UmraoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Academics Stink at Writing - PinkerDocument14 paginiWhy Academics Stink at Writing - PinkerCool MomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement FallaciesDocument8 paginiThesis Statement FallaciesWriteMyPaperSingapore100% (2)

- Theory for Beginners: Children’s Literature as Critical ThoughtDe la EverandTheory for Beginners: Children’s Literature as Critical ThoughtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sovereignty and Its Other: Toward the Dejustification of ViolenceDe la EverandSovereignty and Its Other: Toward the Dejustification of ViolenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical Listening in Action: A Concept-Tactic ApproachDe la EverandRhetorical Listening in Action: A Concept-Tactic ApproachÎncă nu există evaluări

- Portfolio RhetoricDocument1 paginăPortfolio Rhetoricapi-285144457Încă nu există evaluări

- Reflecting on Reflexivity: The Human Condition as an Ontological SurpriseDe la EverandReflecting on Reflexivity: The Human Condition as an Ontological SurpriseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essays For To Kill A MockingbirdDocument7 paginiEssays For To Kill A Mockingbirdkbmbwubaf100% (2)

- 16 A Response To My CriticsDocument13 pagini16 A Response To My CriticsDaysilirionÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Burdens of Perfection: On Ethics and Reading in Nineteenth-Century British LiteratureDe la EverandThe Burdens of Perfection: On Ethics and Reading in Nineteenth-Century British LiteratureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sarcasm PaperDocument13 paginiSarcasm Paperapi-219804660Încă nu există evaluări

- How To Do Well in A2 English Literature CourseworkDocument6 paginiHow To Do Well in A2 English Literature Courseworkf675ztsf100% (1)

- Romantics at War: Glory and Guilt in the Age of TerrorismDe la EverandRomantics at War: Glory and Guilt in the Age of TerrorismEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- How Fear Works: Culture of Fear in the Twenty-First CenturyDe la EverandHow Fear Works: Culture of Fear in the Twenty-First CenturyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (2)

- Envision in Depth: Reading, Writing, and Researching Arguments - Chapter 1Document41 paginiEnvision in Depth: Reading, Writing, and Researching Arguments - Chapter 1Ocheze0% (1)

- Summary of The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left | Conversation StartersDe la EverandSummary of The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left | Conversation StartersEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Steven Pinker, Why Academic Writing SucksDocument22 paginiSteven Pinker, Why Academic Writing SuckslalouruguayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allegories of America: Narratives, Metaphysics, PoliticsDe la EverandAllegories of America: Narratives, Metaphysics, PoliticsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educational Justice: Liberal Ideals, Persistent Inequality, and the Constructive Uses of CritiqueDe la EverandEducational Justice: Liberal Ideals, Persistent Inequality, and the Constructive Uses of CritiqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power and International Relations: A Conceptual ApproachDe la EverandPower and International Relations: A Conceptual ApproachEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- Literary Research PaperDocument11 paginiLiterary Research PaperCookieButterNuggetsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Undergraduate Thesis International RelationsDocument6 paginiUndergraduate Thesis International RelationsThesisPapersForSaleUK100% (2)

- The Styles in The American Politics Volume I: A NarrationDe la EverandThe Styles in The American Politics Volume I: A NarrationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cracking Open The IQ BoxDocument14 paginiCracking Open The IQ BoxcarlosnestorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Middling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyDe la EverandMiddling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusDe la EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (22)

- Salam Rushdie Rhet AnDocument2 paginiSalam Rushdie Rhet Anapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- OrwellDocument2 paginiOrwellapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Huck FinnDocument2 paginiHuck Finnapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Columbus EssayDocument2 paginiColumbus Essayapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- CowbrDocument4 paginiCowbrapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- CPBRDocument3 paginiCPBRapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Poetry Unit - Personal PoemsDocument3 paginiPoetry Unit - Personal Poemsapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Love at First SightDocument8 paginiLove at First Sightapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Delaney Creative Writing AssignmentDocument1 paginăDelaney Creative Writing Assignmentapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Holocaust Remembrance ReflectionDocument2 paginiHolocaust Remembrance Reflectionapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Hs EssayDocument3 paginiHs Essayapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Snow - Look Beyond ItDocument4 paginiSnow - Look Beyond Itapi-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Draft of Coadf EssayDocument4 paginiFinal Draft of Coadf Essayapi-255704986100% (1)

- Reading Journal Entry 1Document1 paginăReading Journal Entry 1api-255704986Încă nu există evaluări

- Adverbs of Manner - Quiz 2 - SchoologyDocument3 paginiAdverbs of Manner - Quiz 2 - SchoologyGrover VillegasÎncă nu există evaluări

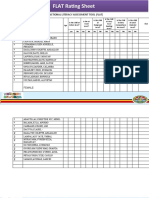

- Grade 2 Clamaris FUNCTIONAL-LITERACY-ASSESSMENT-TOOLDocument4 paginiGrade 2 Clamaris FUNCTIONAL-LITERACY-ASSESSMENT-TOOLBabie Jane Lastimosa ClamarisLptÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ezra PerezDocument2 paginiEzra PerezEzra PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- AlegDocument16 paginiAleghamana SinangkadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizal's Life & Work Module 6 AnswersDocument2 paginiRizal's Life & Work Module 6 AnswersRimari Gabrielle BriozoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Concise Public Speaking Handbook 6Th Edition Steven A Beebe Full ChapterDocument67 paginiA Concise Public Speaking Handbook 6Th Edition Steven A Beebe Full Chapteralfred.jessie484100% (7)

- Evaluation of Training in Organizations A Proposal For An Integrated ModelDocument24 paginiEvaluation of Training in Organizations A Proposal For An Integrated ModelYulia Noor SariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Third Quarter English 6Document8 paginiThird Quarter English 6Melchor FerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math 7 - Q3 M5Document13 paginiMath 7 - Q3 M5Steven Louis UyÎncă nu există evaluări

- VTDI - Student Handbook 2020-2021Document85 paginiVTDI - Student Handbook 2020-2021Dre's Graphic DesignsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument12 paginiCambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDena KaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- First (FCE) - SpeakingDocument7 paginiFirst (FCE) - SpeakingAmpy Varela RíosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demo18 MusicDocument4 paginiDemo18 MusicJofranco Gamutan Lozano0% (1)

- Quality Management - Course Outline - 91-92 PDFDocument5 paginiQuality Management - Course Outline - 91-92 PDFtohidi_mahboobeh_223Încă nu există evaluări

- Fresno Student Sex Education Survey: About YouDocument2 paginiFresno Student Sex Education Survey: About YouMunee AnsariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thinking Skills Sample PaperDocument14 paginiThinking Skills Sample PaperCamloc LuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 11 English Lesson PlanDocument6 paginiGrade 11 English Lesson PlanFGacadSabado100% (2)

- Research 3Document21 paginiResearch 3johnjester marasiganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal ResumeDocument7 paginiLegal ResumeThomas Edwards100% (2)

- Instructional ProcedureDocument3 paginiInstructional ProcedureMuni MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ch15 HyperglycemicEmergenciesDocument21 paginiCh15 HyperglycemicEmergenciesBader ZawahrehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practice Test 1 I. Lexico-Grammar A. Circle The Word or Phrase That Best Completes Each Sentence A, B, C or DDocument5 paginiPractice Test 1 I. Lexico-Grammar A. Circle The Word or Phrase That Best Completes Each Sentence A, B, C or DSunshine HannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review Form (Ipcrf) For Master Teacher I-IvDocument6 paginiIndividual Performance Commitment and Review Form (Ipcrf) For Master Teacher I-IvBenj Alejo100% (1)

- Sc1a Assessment 1Document29 paginiSc1a Assessment 1api-435791379Încă nu există evaluări

- Team InterventionsDocument13 paginiTeam InterventionsSowmyaRajendranÎncă nu există evaluări

- For Print September PDF 9.0Document547 paginiFor Print September PDF 9.0sokolpacukaj100% (1)

- Subimal Mishra - EczematousDocument3 paginiSubimal Mishra - EczematousGregory Eleazar D. AngelesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nurs 5327 060 Syllabus Assignment CtuckerDocument11 paginiNurs 5327 060 Syllabus Assignment Ctuckerapi-355627879Încă nu există evaluări

- Vision: Institute of Integrated Electrical Engineers of The Philippines, IncDocument12 paginiVision: Institute of Integrated Electrical Engineers of The Philippines, IncCinderella WhiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Francais sport-WORKSHEETDocument1 paginăFrancais sport-WORKSHEETrite2shinjiniÎncă nu există evaluări