Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Historiography

Încărcat de

dobojac73Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Historiography

Încărcat de

dobojac73Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Historiography

1

Historiography

Historiography refers either to the study of the methodology and development of "history" (as a discipline), or to a

body of historical work on a specialized topic. Scholars discuss historiography topically such as the

"historiography of Catholicism", the "historiography of early Islam", or the "historiography of China" as well as

specific approaches and genres, such as political history and social history. Beginning in the nineteenth century, with

the ascent of academic history, a corpus of historiographic literature developed. How much are historians influenced

by their own groups and loyalties--such as to their nation state--is a much debated question.

[1]

The research interests of historians change over time, and in recent decades there has been a shift away from

traditional diplomatic, economic and political history toward newer approaches, especially social and cultural

studies. From 1975 to 1995, the proportion of professors of history in American universities identifying with social

history rose from 31% to 41%, while the proportion of political historians fell from 40% to 30%.

[2]

In the history

departments of British universities in 2007, of the 5,723 faculty members, 1,644 (29%) identified themselves with

social history while political history came next with 1,425 (25%).

[3]

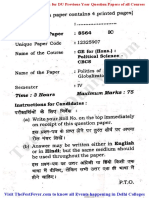

Allegory on writing history by

Jacob de Wit (1754). An almost

naked Truth keeps an eye on the

writer of history. Wisdom gives

advice; with PtolemyI Soter, a

master in objectivity in his book on

Alexander the Great, below in

profile.

Terminology

In the early modern period, the term historiography tended to be used in a more

basic sense, to mean simply "the writing of history". Historiographer therefore

meant "historian", and it is in this sense that certain official historians were given

the title "Historiographer Royal", in Sweden (from 1618), England (from 1660),

and Scotland (from 1681). The Scottish post is still in existence.

Defining historiography

Furay and Salevouris (1988) define historiography as "the study of the way

history has been and is written the history of historical writing... When you

study 'historiography' you do not study the events of the past directly, but the

changing interpretations of those events in the works of individual historians."

[4]

Narrative

According to Lawrence Stone, narrative has traditionally been the main rhetorical

device used by historians. In 1979, at a time when the new Social History was

demanding a social-science model of analysis, Stone detected a move back toward

the narrative. Stone defined narrative as follows: it is organized chronologically; it

is focused on a single coherent story; it is descriptive rather than analytical; it is

concerned with people not abstract circumstances; and it deals with the particular

and specific rather than the collective and statistical. He reported that, "More and

more of the 'new historians' are now trying to discover what was going on inside

people's heads in the past, and what it was like to live in the past, questions which

inevitably lead back to the use of narrative."

[5]

Historians committed to a social science approach, however, have criticized the

narrowness of narrative and its preference for anecdote over analysis, and its use

of clever examples rather than statistically verified empirical regularities.

[6]

Historiography

2

Topics studied

Some of the common topics in historiography are:

1. Reliability of the sources used, in terms of authorship, credibility of the author, and the authenticity or corruption

of the text. (See also source criticism).

2. Historiographical tradition or framework. Every historian uses one (or more) historiographical traditions, for

example Marxist, Annales School, "total history", or political history.

3. Moral issues, guilt assignment, and praise assignment

4. Revisionism versus orthodox interpretations

5. Historical metanarratives

The history of written history

Understanding the past appears to be a universal human need, and the telling of history has emerged independently

in civilisations around the world. What constitutes history is a philosophical question (see philosophy of history).

The earliest chronologies date back to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, though no historical writers in these early

civilizations were known by name. For the purposes of this article, history is taken to mean written history recorded

in a narrative format for the purpose of informing future generations about events. Some experts have advised

against the tendency to extrapolate trends for historical patterns that do not align with expectations about the

future.

[7]

Hellenic world

Reproduction of part of a

tenth-century copy of Thucydides's

History of the Peloponnesian War.

The earliest known systematic historical thought emerged in ancient Greece, a

development which would be an important influence on the writing of history

elsewhere around the Mediterranean region. Greek historians greatly contributed

to the development of historical methodology. The earliest known critical

historical works were The Histories, composed by Herodotus of Halicarnassus

(484 c. 425BCE) who later became known as the "father of history" (Cicero).

Herodotus attempted to distinguish between more and less reliable accounts, and

personally conducted research by travelling extensively, giving written accounts

of various Mediterranean cultures. Although Herodotus' overall emphasis lay on

the actions and characters of men, he also attributed an important role to divinity

in the determination of historical events.

The generation following Herodotus witnessed a spate of local histories of the

individual city-states (poleis), written by the first of the local historians who employed the written archives of city

and sanctuary. Dionysius of Halicarnassus characterized these historians as the forerunners of Thucydides,

[8]

and

these local histories continued to be written into Late Antiquity, as long as the city-states survived. Two early figures

stand out: Hippias of Elis, who produced the lists of winners in the Olympic Games that provided the basic

chronological framework as long as the pagan classical tradition lasted, and Hellanicus of Lesbos, who compiled

more than two dozen histories from civic records, all of them now lost.

Thucydides largely eliminated divine causality in his account of the war between Athens and Sparta, establishing a

rationalistic element which set a precedent for subsequent Western historical writings. He was also the first to

distinguish between cause and immediate origins of an event, while his successor Xenophon (c. 431 355BCE)

introduced autobiographical elements and character studies in his Anabasis.

The proverbial Philippic attacks of the Athenian orator Demosthenes (384322BCE) on PhilipII of Macedon marked

the height of ancient political agitation. The now lost history of Alexander's campaigns by the diadoch PtolemyI

(367283BCE) may represent the first historical work composed by a ruler. Polybius (c. 203 120BCE) wrote on the

Historiography

3

rise of Rome to world prominence, and attempted to harmonize the Greek and Roman points of view.

The Chaldean priest Berossus (fl. 3rd centuryBCE) composed a Greek-language History of Babylonia for the

Seleucid king AntiochusI, combining Hellenistic methods of historiography and Mesopotamian accounts to form a

unique composite. Reports exist of other near-eastern histories, such as that of the Phoenician historian

Sanchuniathon; but he is considered semi-legendary and writings attributed to him are fragmentary, known only

through the later historians Philo of Byblos and Eusebius, who asserted that he wrote before even the Trojan war.

Roman world

The Romans adopted the Greek tradition, writing at first in Greek, but eventually chronicling their history in a

freshly non-Greek language.

[citation needed]

While early Roman works were still written in Greek, the Origines,

composed by the Roman statesman Cato the Elder (234149BCE), was written in Latin, in a conscious effort to

counteract Greek cultural influence. It marked the beginning of Latin historical writings. Hailed for its lucid style,

Julius Caesar's (10044BCE) Bellum Gallicum exemplifies autobiographical war coverage. The politician and orator

Cicero (10643BCE) introduced rhetorical elements in his political writings.

Strabo (63BCE c. 24CE) was an important exponent of the Greco-Roman tradition of combining geography with

history, presenting a descriptive history of peoples and places known to his era. Livy (59BCE 17CE) records the

rise of Rome from city-state to empire. His speculation about what would have happened if Alexander the Great had

marched against Rome represents the first known instance of alternate history.

[9]

Biography, although popular throughout antiquity, was introduced as a branch of history by the works of Plutarch (c.

46 127CE) and Suetonius (c. 69 after 130CE) who described the deeds and characters of ancient personalities,

stressing their human side. Tacitus (c. 56 c. 117CE) denounces Roman immorality by praising German virtues,

elaborating on the topos of the Noble savage.

China

First page of the Shiji.

In China, the Classic of History is one of the Five Classics of Chinese classic

texts and one of the earliest narratives of China. The Spring and Autumn Annals,

the official chronicle of the State of Lu covering the period from 722 to 481BCE,

is among the earliest surviving Chinese historical texts to be arranged on

annalistic principles. It is traditionally attributed to Confucius. The Zuo Zhuan,

attributed to Zuo Qiuming in the 5th centuryBCE, is the earliest Chinese work of

narrative history and covers the period from 722 to 468BCE. Zhan Guo Ce was a

renowned ancient Chinese historical compilation of sporadic materials on the

Warring States period compiled between the 3rd and 1st centuriesBCE.

Sima Qian (around 100BCE) was the first in China to lay the groundwork for

professional historical writing. His written work was the Shiji (Records of the

Grand Historian), a monumental lifelong achievement in literature. Its scope

extends as far back as the 16th centuryBCE, and it includes many treatises on

specific subjects and individual biographies of prominent people, and also

explores the lives and deeds of commoners, both contemporary and those of previous eras. His work influenced

every subsequent author of history in China, including the prestigious Ban family of the Eastern Han Dynasty era.

Traditional Chinese historiography describes history in terms of dynastic cycles. In this view, each new dynasty is

founded by a morally righteous founder. Over time, the dynasty becomes morally corrupt and dissolute. Eventually,

the dynasty becomes so weak as to allow its replacement by a new dynasty.

[10]

Historiography

4

Christendom

Christian historiography began early, perhaps as early as Luke-Acts, which is the primary source for the Apostolic

Age, though its historical reliability is disputed. In the first Christian centuries, the New Testament canon was

developed. The growth of Christianity and its enhanced status in the Roman Empire after ConstantineI (see State

church of the Roman Empire) led to the development of a distinct Christian historiography, influenced by both

Christian theology and the nature of the Christian Bible, encompassing new areas of study and views of history. The

central role of the Bible in Christianity is reflected in the preference of Christian historians for written sources,

compared to the classical historians' preference for oral sources and is also reflected in the inclusion of politically

unimportant people. Christian historians also focused on development of religion and society. This can be seen in the

extensive inclusion of written sources in the Ecclesiastical History written by Eusebius of Caesarea around 324 and

in the subjects it covers.

[11]

Christian theology considered time as linear, progressing according to divine plan. As

God's plan encompassed everyone, Christian histories in this period had a universal approach. For example,

Christian writers often included summaries of important historical events prior to the period covered by the work.

[12]

A page of Bede's Ecclesiastical

History of the English People

Writing history was popular among Christian monks and clergy in the Middle

Ages. They wrote about the history of Jesus Christ, that of the Church and that of

their patrons, the dynastic history of the local rulers. In the Early Middle Ages

historical writing often took the form of annals or chronicles recording events

year by year, but this style tended to hamper the analysis of events and causes.

[13]

An example of this type of writing is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, which were

the work of several different writers: it was started during the reign of Alfred the

Great in the late 9thcentury, but one copy was still being updated in 1154. Some

writers in the period did construct a more narrative form of history. These

included Gregory of Tours, and more successfully Bede who wrote both secular

and ecclesiastical history and is known for writing the Ecclesiastical History of

the English People.

[11]

During the Renaissance, history was written about states or nations. The study of

history changed during the Enlightenment and Romanticism. Voltaire described

the history of certain ages that he considered important, rather than describing

events in chronological order. History became an independent discipline. It was not called philosophia historiae

anymore, but merely history (historia).

Islamic world

Muslim historical writings first began to develop in the 7th century, with the reconstruction of the Prophet

Muhammad's life in the centuries following his death. With numerous conflicting narratives regarding Muhammad

and his companions from various sources, it was necessary to verify which sources were more reliable. In order to

evaluate these sources, various methodologies were developed, such as the "science of biography", "science of

hadith" and "Isnad" (chain of transmission). These methodologies were later applied to other historical figures in the

Islamic civilization. Famous historians in this tradition include Urwah (d.712), Wahb ibn Munabbih (d.728), Ibn

Ishaq (d.761), al-Waqidi (745822), Ibn Hisham (d.834), Muhammad al-Bukhari (810870) and Ibn Hajar

(13721449).

Historians of the medieval Islamic world also developed an interest in world history. The historian Muhammad ibn

Jarir al-Tabari (838923) is known for writing a detailed and comprehensive chronicle of Mediterranean and Middle

Eastern history in his History of the Prophets and Kings in 915. Until the 10thcentury, history most often meant

political and military history, but this was not so with Persian historian Biruni (9731048). In his Kitab fi Tahqiq ma

l'il-Hind (Researches on India) he did not record political and military history in any detail, but wrote more on

India's cultural, scientific, social and religious history. He expanded on his idea of history in another work, The

Historiography

5

Chronology of the Ancient Nations.

[14]

Biruni is considered the father of Indology for his detailed studies on Indian

history.

[15]

Archaeology in the Middle East began with the study of the ancient Near East by Muslim historians in the medieval

Islamic world who developed an interest in learning about pre-Islamic cultures. In particular, they most often

concentrated on the archaeology and history of pre-Islamic Arabia, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. In Egyptology,

the first known attempts at deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs were made in Islamic Egypt by Dhul-Nun al-Misri and

Ibn Wahshiyya in the 9th century, who were able to at least partly understand what was written in the ancient

Egyptian hieroglyphs, by relating them to the contemporary Coptic language used by Coptic priests in their

time.

[citation needed]

Muslim historians such as Abu al-Hassan al-Hamadani of Yemen (d. 945), Abdul Latif

al-Baghdadi (11621231) and Al-Idrisi of Egypt (d. 1251) developed elaborate archaeological methods which they

employed in their excavations and research of ancient archaeological sites.

[16]

Tunisian statue of Ibn Khaldun, pioneer of

historiography, cultural history, and the

philosophy of history.

Islamic historical writing eventually culminated in the works of the

Arab Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun (13321406), who published his

historiographical studies in the Muqaddimah (translated as

Prolegomena) and Kitab al-I'bar (Book of Advice).

[17]

Among many

other things, his Muqaddimah laid the groundwork for the observation

of the roles of the state, in history,

[18]

and he discussed the rise and fall

of civilizations. He also developed a method for the study of history,

and is thus considered to be the founder of Arab historiography,

[19][][]

or the "father of the philosophy of history".

[20]

In the preface to the

Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun warned of seven mistakes that he thought

historians often committed. In this criticism, he approached the past as

strange and in need of interpretation. The originality of Ibn Khaldun

was to claim that the cultural differences of another age must govern

the evaluation of relevant historical material, to distinguish the

principles according to which it might be possible to attempt the

evaluation, and lastly, to consider the need for experience, in addition

to rational principles, in order to assess a culture of the past. Ibn

Khaldun often criticized "idle superstition and uncritical acceptance of

historical data." As a result, he introduced a method to the study of

history, which was considered something "new to his age", and he

often referred to it as his "new science", now associated with historiography.

[21]

The Muqaddimah is also the earliest

known work to critically examine military history, criticizing certain accounts of historical battles that appear to be

exaggerated, and takes military logistics into account when questioning the exaggerated sizes of historical armies

reported in earlier sources.

[22]

Historiography

6

Modern era

Voltaire

During the Age of Enlightenment, the French philosophe Voltaire (16941778) had an enormous influence on the

development of historiography through his scrupulous methods and demonstration of fresh new ways to look at the

past. His best-known histories are The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the

Nations (1756).

"My chief object," he wrote in 1739, "is not political or military history, it is the history of the arts, of commerce, of

civilization in a word, of the human mind."

[23]

He broke from the tradition of narrating diplomatic and military

events, and emphasized customs, social history and achievements in the arts and sciences. The "Essay on Customs"

traced the progress of world civilization in a universal context, thereby rejecting both nationalism and the traditional

Christian frame of reference. Influenced by Bossuet's Discourse on the Universal History (1682), he was the first

scholar to make a serious attempt to write the history of the world, eliminating theological frameworks, and

emphasizing economics, culture and political history. He treated Europe as a whole, rather than a collection of

nations. He was the first to emphasize the debt of medieval culture to Arab civilization, but otherwise was weak on

the Middle Ages. Although he repeatedly warned against political bias on the part of the historian, he did not miss

many opportunities to expose the intolerance and frauds of the church over the ages. Voltaire advised scholars that

anything contradicting the normal course of nature was not to be believed. Although he found evil in the historical

record, he fervently believed reason and educating the illiterate masses would lead to progress.

Voltaire explains his view of historiography in his article on "History" in Diderot's Encyclopdie:

"One demands of modern historians more details, better ascertained facts, precise dates, more attention to

customs, laws, mores, commerce, finance, agriculture, population."

Voltaire's histories imposed the values of the Enlightenment on the past, but he helped free historiography from

antiquarianism, Eurocentrism, religious intolerance and a concentration on great men, diplomacy, and warfare.

[24]

Yale professor Peter Gay says Voltaire wrote "very good history," citing his "scrupulous concern for truths," "careful

sifting of evidence," "intelligent selection of what is important," "keen sense of drama," and "grasp of the fact that a

whole civilization is a unit of study."

[25][26]

Germany and the scientific method

Modern historiography emerged in 19th-century German universities, where Leopold von Ranke revolutionized

historiography with his seminars and critical approach; he emphasized politics and diplomacy, dropping the social

and cultural themes Voltaire had highlighted.

[27]

Sources had to be hard, not speculations and rationalizations. His

credo was to write history the way it was. He insisted on primary sources with proven authenticity. Hegel and Marx

introduced the concept of spirit and dialectical materialism, respectively, into the study of world historical

development. Previous historians had focused on cyclical events of the rise and decline of rulers and nations. Process

of nationalization of history, as part of national revivals in 19th century, resulted with separation of "one's own"

history from common universal history by such way of perceiving, understanding and treating the past that

constructed history as history of a nation.

[]

A new discipline, sociology, emerged in the late 19th century and

analyzed and compared these perspectives on a larger scale.

French Annales School of social history

The French Annales School radically changed the focus of historical research in France during the 20th century.

Fernand Braudel wanted history to become more scientific and less subjective, and demanded more quantitative

evidence. Furthermore, he introduced a socio-economic and geographic framework to historical questions. Other

French historians, like Philippe Aris and Michel Foucault, described the history of everyday topics such as death

and sexuality. Carlo Ginzburg and Natalie Zemon Davis pioneered the genre of historical writing sometimes known

Historiography

7

as "microhistory," which attempted to understand the mentalities and decisions of individuals - mostly peasants -

within their limited milieu using contracts, court documents and oral histories.

Foundation of important historical journals

The historical journal, a forum where academic historians could exchange ideas and publish newly discovered

information, came into being in the 19th century. The early journals were similar to those for the physical sciences,

and were seen as a means for history to become more professional. Journals also helped historians to establish

various historiographical approaches, the most notable example of which was Annales. conomies. Socits.

Civilisations., a publication instrumental in establishing the Annales School.

Some historical journals are as follows:

1840 Historisk tidsskrift (Denmark)

1859 Historische Zeitschrift (Germany)

1866 Archivum historicum, later Historiallinen arkisto (Finland, published in Finnish)

1867 Szzadok (Hungary)

1869 asopis Matice moravsk (Czech republic - then part of Austria-Hungary)

1871 Historisk tidsskrift (Norway)

1876 Revue Historique (France)

1881 Historisk tidskrift (Sweden)

1886 English Historical Review (England)

1892 William and Mary Quarterly (USA)

1894 Ons Hmecht (Luxembourg)

1895 American Historical Review (USA)

1895 esk asopis historick (Czech republic - then part of Austria-Hungary)

1914 Mississippi Valley Historical Review (renamed in 1964 the Journal of American History) (USA)

1916 The Journal of Negro History

1916 Historisk Tidskrift fr Finland (Finland, published in Swedish)

1918 Hispanic American historical review

1928 Scandia (Sweden)

1929 Annales d'histoire conomique et sociale

1941 The Journal of Economic History

1952 Past & present: a journal of historical studies (Great Britain)

1953 Vierteljahrshefte fr Zeitgeschichte (Germany)

1956 Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria (Nigeria)

1960 Journal of African History (Cambridge)

1960 Technology and culture: the international quarterly of the Society for the History of Technology (USA)

1967 The Journal of Social History

1969 Journal of Interdisciplinary History

1975 Geschichte und Gesellschaft. Zeitschrift fr historische Sozialwissenschaft (Germany)

1976 Journal of Family History

1978 The Public Historian

1982 Storia della Storiografia History of Historiography Histoire de l'Historiographie Geschichte der

Geschichtsschreibung

[28]

1982 Subaltern Studies (Oxford University Press)

1986 Zeitschrift fr Sozialgeschichte des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts, new title since 2003: Sozial.Geschichte.

Zeitschrift fr historische Analyse des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts

[29]

(Germany)

1990 Gender and history

1990 Journal of World History

Historiography

8

1990 L'Homme. Zeitschrift fr feministische Geschichtswissenschaft

[30]

(Austria)

1990 sterreichische Zeitschrift fr Geschichtswissenschaften (ZG)

[31]

1992 Women's History Review

1993 Historische Anthropologie

[32]

Approaches to history

How a historian approaches historical events is one of the most important decisions within historiography. It is

commonly recognised by historians that, in themselves, individual historical facts dealing with names, dates and

places are not particularly meaningful. Such facts will only become useful when assembled with other historical

evidence, and the process of assembling this evidence is understood as a particular historiographical approach.

The most influential historiographical approaches are:

Comparative history

Cultural history

Diplomatic history

Economic history

Environmental history, a relatively new field

Ethnohistory

Family history

Feminist history

History of Religion and Church History; the history of theology is usually handled under Theology

Intellectual History and History of ideas

Labor history

Latin American History

Local History and Microhistory

Marxist historiography and Historical materialism

Military history, including naval and air

Oral history

Political history

Public history, especially museums and historic preservation

Quantitative history, Cliometrics (in economic history); Prosopography using statistics to study biographies

Shared historical authority

Social history and History from below; along with the French version the Annales School and the German

Bielefeld School

Women's history and Gender history

World history and Universal history

Scholars typically specialize in a particular theme and region. see:

Dark Ages (historiography)

Historical revisionism

Historiography of the British Empire

Historiography of the causes of World War I

Historiography of China

Chinese historiography

Historiography of the Cold War

Historiography of the Crusades

Historiography of early Christianity

Historiography of early Islam

Historiography

9

Historiography of feudalism

Historiography and nationalism

Historiography of the French Revolution

Historiography of science

Historiography of Switzerland

Historiography of the United States

Historiography of the causes of World War I

Historiography of World War II

Roman historiography

Historiography in the Soviet Union

Whig history, emphasizing inevitable progress

Related fields

Important related fields include:

Antiquarianism

Genealogy

Numismatics

Paleography

Philosophy of history

Pseudohistory, that is, false history

References

[1] Marc Ferro, The Use and Abuse of History: Or How the Past Is Taught to Children (2003)

[2] Diplomatic dropped from 5% to 3%, economic history from 7% to 5%, and cultural history grew from 14% to 16%. Based on full-time

professors in U.S. history departments. Stephen H. Haber, David M. Kennedy, and Stephen D. Krasner, "Brothers under the Skin: Diplomatic

History and International Relations," International Security, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Summer, 1997), pp. 3443 at p. 42 online at JSTOR (http:/ /

www.jstor. org/ stable/ 2539326)

[3] See "Teachers of History in the Universities of the UK 2007 listed by research interest" (http:/ / www. history. ac. uk/ ihr/ Resources/

Teachers/ a27. html)

[4] (The Methods and Skills of History: A Practical Guide, 1988, p. 223, ISBN 0-88295-982-4)

[5] Lawrence Stone, "The Revival of Narrative: Reflections on a New Old History," Past and Present 85 (Nov 1979) pp 3-24, quote on p. 13

[6] J. Morgan Kousser, The Revivalism of Narrative: A Response to Recent Criticisms of Quantitative History, Social Science History vol 8,

no. 2 (Spring 1984): 13349; Eric H. Monkkonen, The Dangers of Synthesis, American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (December 1986):

114657.

[8] Dionysius, On Thucydides, 5.

[11] Historiography (http:/ / www.cuw.edu/ Academics/ programs/ history/ historiography. html), Concordia University Wisconsin , retrieved

on 2 November 2007

[12] Warren, John (1998). The past and its presenters: an introduction to issues in historiography, Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-67934-4,

pp. 6768.

[13] Warren, John (1998). The past and its presenters: an introduction to issues in historiography, Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-67934-4,

pp. 7879.

[14] M. S. Khan (1976). "al-Biruni and the Political History of India", Oriens 25, pp. 86115.

[15] Zafarul-Islam Khan, At The Of A New Millennium II (http:/ / milligazette. com/ Archives/ 15-1-2000/ Art5. htm), The Milli Gazette.

[17] S. Ahmed (1999). A Dictionary of Muslim Names. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-356-9.

[18] H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", Cooperation South Journal 1.

[19] Salahuddin Ahmed (1999). A Dictionary of Muslim Names. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-356-9.

[20] Dr. S. W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture 12 (3).

[21] Ibn Khaldun, Franz Rosenthal, N. J. Dawood (1967), The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, p. x, Princeton University Press, ISBN

0-691-01754-9.

[22] Ibn Khaldun, Franz Rosenthal, N. J. Dawood (1967), The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, pp. 112, Princeton University Press,

ISBN 0-691-01754-9.

Historiography

10

[24] Paul Sakmann, "The Problems of Historical Method and of Philosophy of History in Voltaire", History and Theory, Dec 1971, Vol. 11#4 pp

2459

[25] Peter Gay, "Carl Becker's Heavenly City," Political Science Quarterly (1957) 72:182-99

[26] Peter Gay, Voltaire's Politics (2nd ed. 1988)

[27] E. Sreedharan, A textbook of historiography, 500BC to AD2000 (2004) p 185

[29] http:/ / www.stiftung-sozialgeschichte.de/

Bibliography

Theory

Joyce Appleby, Lynn Hunt & Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth About History. New York: W. W. Norton &

Company, 1994.

Michael Bentley, Modern Historiography: An Introduction, 1999 ISBN 0-415-20267-1

Marc Bloch, The Historian's Craft [1940]

Peter Burke, History and Social Theory, Polity Press, Oxford, 1992

David Cannadine (editor), What is History Now, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002

E. H. Carr, What is History? 1961, ISBN 0-394-70391-X

R.G. Collingwood, The Idea of History, 1936, ISBN 0-19-285306-6

Geoffrey Elton, The Practice of History, 1969, ISBN 0-631-22980-9

Richard J. Evans In Defence of History, 1997, ISBN 1-86207-104-7

David Hackett Fischer, Historians' Fallacies: Towards a Logic of Historical Thought, Harper & Row, 1970

Gardiner, Juliet (ed) What is History Today...? London: MacMillan Education Ltd., 1988.

Harlaftis, Gelina, ed. The New Ways of History: Developments in Historiography (I.B. Tauris, 2010) 260 pages;

trends in historiography since 1990

Keith Jenkins, ed. The Postmodern History Reader (2006)

Keith Jenkins, Rethinking History, 1991, ISBN 0-415-30443-1

Arthur Marwick, The New Nature of History: knowledge, evidence, language, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001, ISBN

0-333-96447-0

Alun Munslow. The Routledge Companion to Historical Studies (2000)

Roger Spalding & Christopher Parker, Historiography: An Introduction, 2008, ISBN 0-7190-7285-9

John Tosh, The Pursuit of History, 2002, ISBN 0-582-77254-0

Aviezer Tucker, ed. A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography Malden: Blackwell, 2009

Hayden White, The Fiction of Narrative: Essays on History, Literature, and Theory, 19572007, Johns Hopkins,

2010. Ed. Robert Doran

Guides to scholarship

Allison, William Henry. A guide to historical literature (1931) comprehensive bibliography for scholarship to

1930. online edition (http:/ / quod. lib. umich. edu/ cgi/ t/ text/ text-idx?c=acls;cc=acls;view=toc;idno=heb06297.

0001. 001)

Gray, Wood. Historian's Handbook, 2nd ed. (Houghton-Miffin Co., cop. 1964), vii, 88 p.

Loades, David, ed. Reader's Guide to British History (Routledge; 2 vol 2003) 1760pp; highly detailed guide to

British historiography excerpt and text search (http:/ / books. google. com/ books?id=AYEYAQAAIAAJ)

Norton, Mary Beth, ed. The American Historical Association's guide to historical literature (Oxford University

Press, 1995) vol 1 online (http:/ / hdl. handle. net/ 2027/ heb. 06298), vol 2 online (http:/ / hdl. handle. net/ 2027/

heb. 06298)

Parish, Peter, ed. Reader's Guide to American History (Routledge, 1997), 880 pp; detailed guide to historiography

of American topics excerpt and text search (http:/ / books. google. com/ books?id=DnQTAXf4NuIC)

Historiography

11

Woolf, Daniel, et al. The Oxford History of Historical Writing (5 vol 2011-12), covers all major historians since

AD 600; see listings (http:/ / www. amazon. com/ gp/ search/ ref=sr_adv_b/ ?search-alias=stripbooks&

unfiltered=1& field-keywords=& field-author=& field-title="The+ Oxford+ History+ of+ Historical+ Writing:+

& field-isbn=& field-publisher=& node=& field-p_n_condition-type=& field-feature_browse-bin=&

field-subject=& field-language=& field-dateop=During& field-datemod=& field-dateyear=&

sort=relevanceexprank& Adv-Srch-Books-Submit. x=0& Adv-Srch-Books-Submit. y=0)

Histories of historical writing

Barnes, Harry Elmer. A history of historical writing (1962)

Barraclough, Geoffrey. History: Main Trends of Research in the Social and Human Sciences, (1978)

Bentley, Michael. ed., Companion to Historiography, Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0415285577: 39 chapters by

experts

Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval and Modern, 3rd edition, 2007, ISBN 0-226-07278-9

Budd, Adam, ed. The Modern Historiography Reader: Western Sources. London: Routledge, 2009.

Cohen, H. Floris The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry, Chicago, 1994, ISBN 0-226-11280-2

Conrad, Sebastian. The Quest for the Lost Nation: Writing History in Germany and Japan in the American

Century (2010)

Gilderhus, Mark T. History an Historiographical Introduction, 2002, ISBN 0-13-044824-9

Iggers, Georg G. Historiography in the 20th Century: From Scientific Objectivity to the Postmodern Challenge

(2005)

Kramer, Lloyd, and Sarah Maza, eds. A Companion to Western Historical Thought Blackwell 2006. 520pp; ISBN

978-1-4051-4961-7.

Momigliano, Arnaldo. The Classical Foundation of Modern Historiography, 1990, ISBN 978-0-226-07283-8

Rahman, M. M. ed. Encyclopaedia of Historiography (2006) Excerpt and text search (http:/ / books. google. com/

books?id=1BhtHVHgnwAC& dq=historiography+ "joseph+ priestly"& lr=& as_drrb_is=q& as_minm_is=0&

as_miny_is=& as_maxm_is=0& as_maxy_is=& as_brr=0& source=gbs_navlinks_s)

Thompson, James Westfall. A History of Historical Writing. vol 1: From the earliest Times to the End of the 17th

Century (1942) online edition (http:/ / www. questia. com/ PM. qst?a=o& d=9276002); A History of Historical

Writing. vol 2: The 18th and 19th Centuries (1942) online edition (http:/ / www. questia. com/ PM. qst?a=o&

d=58613485)

Woolf, Daniel, ed. A Global Encyclopedia of Historical Writing (2 vol. 1998)

Woolf, Daniel. "Historiography", in New Dictionary of the History of Ideas, ed. M.C. Horowitz, (2005), vol. I.

Woolf, Daniel. A Global History of History (Cambridge University Press, 2011)

Woolf, Daniel, ed. The Oxford History of Historical Writing. 5 vols. (Oxford University Press, 201112).

Feminist historiography

Bonnie G. Smith, The Gender of History: Men, Women, and Historical Practice, Harvard University Press 2000

Gerda Lerner, The Majority Finds its Past: Placing Women in History, New York: Oxford University Press 1979

Judith M. Bennett, History Matters: Patriarchy and the Challenge of Feminism, University of Pennsylvania Press,

2006

Julie Des Jardins, Women and the Historical Enterprise in America, University of North Carolina Press, 2002

Mary Ritter Beard, Woman as force in history: A study in traditions and realities

Mary Spongberg, Writing women's history since the Renaissance, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002

Historiography

12

National and regional studies

Berger, Stefan et al., eds. Writing National Histories: Western Europe Since 1800 (1999) excerpt and text search

(http:/ / www. amazon. com/ Writing-National-Histories-Western-Europe/ dp/ 0415164265/ ); how history has

been used in Germany, France & Italy to legitimize the nation-state against socialist, communist and Catholic

internationalism

Iggers, Georg G. A new Directions and European Historiography (1975)

LaCapra, Dominic, and Stephen L. Kaplan, eds. Modern European Intellectual History: Reappraisals and New

Perspective (1982)

United States

Hofstadter, Richard. The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington (1968)

Novick, Peter. That Noble Dream: The "Objectivity Question" and the American Historical Profession (1988),

ISBN 0-521-34328-3

Palmer, William W. "All Coherence Gone? A Cultural History of Leading History Departments in the United

States, 19702010," Journal of The Historical Society (2012), 12: 111153. doi:

10.1111/j.1540-5923.2012.00360.x

Palmer, William. Engagement with the Past: The Lives and Works of the World War II Generation of Historians

(2001)

Parish, Peter J., ed. Reader's Guide to American History (1997), historiographical overview of 600 topics

Wish, Harvey. The American Historian (1960), covers pre-1920

Britain

Cannadine, David. In Churchils Shadow: Confronting the Passed in Modern Britain (2003)

Hexter, J. H. On Historians: Reappraisals of some of the makers of modern history (1979; covers Carl Becker,

Wallace Ferguson, Fernan Braudel, Lawrence Stone, Christopher Hill, and J.G.A. Pocock

Kenyon, John. The History Men: The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance (1983)

Loades, David. Reader's Guide to British History (2 vol. 2003) 1700pp; 1600-word-long historiographical essays

on about 1000 topics

British Empire

Berger, Carl. Writing Canadian History: Aspects of English Canadian Historical Writing since 1900, (2nd ed.

1986)

Bhattacharjee, J. B. Historians and Historiography of North East India (2012)

Davison, Graeme. The Use and Abuse of Australian History, (2000) online edition (http:/ / www. questia. com/

library/ book/ the-use-and-abuse-of-australian-history-by-graeme-davison. jsp)

Farrell, Frank. Themes in Australian History: Questions, Issues and Interpretation in an Evolving Historiography

(1990)

Gare, Deborah. "Britishness in Recent Australian Historiography," The Historical Journal, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Dec.,

2000), pp.11451155 in JSTOR (http:/ / www. jstor. org/ stable/ 3020885)

Guha, Ranajiit. Dominance Without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India (Harvard UP, 1998)

Granatstein, J. L. Who Killed Canadian History? (2000)

Mittal, S. C India distorted: A study of British historians on India (1995), on 19th century writers

Saunders, Christopher. The making of the South African past: major historians on race and class, (1988)

Winks, Robin, ed. The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume V: Historiography (2001)

Historiography

13

Asia and Africa

Cohen, Paul. Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese Past. New York,

London:: Columbia University Press, Studies of the East Asian Institute, 1984. 237p. Reprinted: 2010, with a

New Introduction by the Author. ISBN 023152546X. (http:/ / www. worldcat. org/ title/

discovering-history-in-china-american-historical-writing-on-the-recent-chinese-past/ oclc/ 456728837/ viewport)

Marcinkowski, M. Ismail. Persian Historiography and Geography: Bertold Spuler on Major Works Produced in

Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, India and Early Ottoman Turkey (Singapore: Pustaka Nasional, 2003)

Martin, Thomas R. Herodotus and Sima Qian: The First Great Historians of Greece and China: A Brief History

with Documents (2009)

Yerxa, Donald A. Recent Themes in the History of Africa and the Atlantic World: Historians in Conversation

(2008) excerpt and text search (http:/ / www. amazon. com/ Recent-Themes-History-Africa-Atlantic/ dp/

1570037574/ )

France

Revel, Jacques, and Lynn Hunt, eds. Histories: French Constructions of the Past, (1995). 654pp; 65 essays by

French historians

Stoianovich, Traian. French Historical Method: The Annales Paradigm (1976)

Germany

Iggers, Georg G. The German Conception of History: The National Tradition of Historical Thought from Herder

to the Present (2nd ed. 1983)

Themes, organizations, and teaching

Carlebach, Elishiva, et al. eds. Jewish History and Jewish Memory: Essays in Honor of Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi

(1998) excerpt and text search (http:/ / www. amazon. com/ Jewish-History-Memory-Yerushalmi-Institute/ dp/

0874518717/ )

Charlton, Thomas L. History of Oral History: Foundations and Methodology (2007)

Darcy, R. and Richard C. Rohrs, A Guide to Quantitative History (1995)

Dawidowicz, Lucy S. The Holocaust and Historians. (1981).

Ernest, John. Liberation Historiography: African American Writers and the Challenge of History, 17941861.

(2004)

Evans, Ronald W. The Hope for American School Reform: The Cold War Pursuit of Inquiry Learning in Social

Studies(Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 265 pages

Ferro, Mark, Cinema and History (1988)

Hudson, Pat. History by Numbers: An Introduction to Quantitative Approaches (2002)

Keita, Maghan. Race and the Writing of History. Oxford UP (2000)

Leavy, Patricia. Oral History: Understanding Qualitative Research (2011) excerpt and text search (http:/ / www.

amazon. com/ Oral-History-Understanding-Qualitative-Research/ dp/ 0195395093/ )

Loewen, James W. Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, (1996)

Manning, Patrick, ed. World History: Global And Local Interactions (2006)

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History (2005), ISBN 1-85984-513-4

Ritchie, Donald A. The Oxford Handbook of Oral History (2010) excerpt and text search (http:/ / www. amazon.

com/ Oxford-Handbook-Oral-History-Handbooks/ dp/ 019533955X/ )

Historiography

14

Journals

Cromohs cyber review of modern historiography (http:/ / www. cromohs. unifi. it/ index. html)

History and Theory

History of Historiography (http:/ / www. cisi. unito. it/ stor/ home. htm)

External links

BBC Historiography Guide (http:/ / www-open2-net-vip2. open. ac. uk/ history/ natureofhistory/ index. html)

International Commission for the History and Theory of Historiography (http:/ / www.

historiographyinternational. org/ )

Philosophy of History (http:/ / www. galilean-library. org/ int18. html) introduced at The Galilean Library

'Postcolonial Historiographies' group at Cambridge University (http:/ / www. crassh. cam. ac. uk/ page/ 189/

postcolonial-empires. htm), Includes online reading & video archive

Scientific Historiography (http:/ / www. galilean-library. org/ tucker. html), explained in an interview with

Aviezer Tucker at the Galilean Library

Series of accessible, interactive online lectures (http:/ / www. activehistory. co. uk/ historiography/ index. htm)

Summary of key historiographical schools (http:/ / www. cusd. chico. k12. ca. us/ ~bsilva/ ib/ histo. html)

Web Portal on Historiography and Historical Culture (http:/ / www. culturahistorica. es/ welcome. html)

Article Sources and Contributors

15

Article Sources and Contributors

Historiography Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=566277374 Contributors: 100110100, 777sms, AFA pony, AaronAgassi, Adbarnhart, Adul, Aetheling, Alex S, Alex756,

Alfonso Mrquez, Amandajm, Andrew Gray, Andycjp, Angel ivanov angelov, Angela, Antidiskriminator, Aphaia, Avraham, Barbatus, BarrowHill67, Bastante, Bcorr, Besednjak, BillMasen,

Birdoman, BirgerH, Blue-Haired Lawyer, Bobblehead, BrentS, Brian0918, Brosi, Browns2, Brunnock, Bryan Derksen, Byelf2007, CWH, Can't sleep, clown will eat me, Ceedjee, Cesium 133,

Cessator, Cethegus, Chalst, Charles Matthews, Cherubinirules, ChrisGualtieri, Chubbles, Codex Sinaiticus, Conversion script, Corto lu, Cropthorne24, Cruccone, D, DannyScL, Darklilac,

DarwinPeacock, Davidkazuhiro, Deb, Deeceevoice, Delfeye, Dialectric, DocWatson42, DonAByrd, Doric Loon, Dreftymac, Drmies, Dv82matt, Dweller, Edward, EdwardLane, Ehrenkater,

Eieio687, Ekotkie, El C, Ellywa, Enkyo2, Erianna, Eric Forste, Erujiu12, Escape Orbit, Fastfission, Finetooth, Flammingo, Flufybumblebee, FlyHigh, FocalPoint, Fokion, Fred Bauder, Gaius

Cornelius, Galaxander, Gallador, Gdr, Geni, Ginsengbomb, Golbez, Graham Lippiatt, Gregbard, Greyhood, GrindtXX, Guardian of the Rings, Gun Powder Ma, Haeinous, HaugenErik, Honaroog,

Howsa12, Hyacinth, IZAK, Iblardi, Igiffin, Ishmaelblues, Itsmejudith, Ivan Bajlo, IvanLanin, J a1, J04n, JHK, JaGa, Jagged 85, Jaruvl, Jdrice8, Jdubowsky, Jet66, Joel Bastedo, Johnbod, Jojit fb,

Joseph Solis in Australia, Jrb, Juggleandhope, Kaliz, Kaly99, Kanbun, Kansas Bear, Katherine Tredwell, Kazu89, Kdbuffalo, Khazar2, King of Corsairs, KnightRider, Korath, Kozuch, La

comadreja, Lampros, Lapaz, LibLord, Lightmouse, LilHelpa, Livia augsta, Livia augusta, LordGulliverofGalben, Loren Rosen, Lotje, Lubar, Lumos3, Macedonian, Macrakis, Madalibi,

Magioladitis, Mani1, Marek69, Mariposa740, Mark viking, Markeilz, Markus451, Matt Sheard UK, Matt28, Maurreen, Mav, Melizg, Memanni, Metabolome, Mhazard9, Michael Hardy,

Minority2005, Mistakefinder, Mootros, Msrasnw, NOLA504ever, NSR, Nectarflowed, Nescio, NewEnglandYankee, Noclevername, North Shoreman, Nug, Numbermaniac, Oda Mari,

OffiMcSpin, Olegwiki, Olivier, Omegatron, Ontoraul, Optimist on the run, Palaeovia, Paul A, Peregrine981, PericlesofAthens, Persian Poet Gal, Peter Kirby, Pollinosisss, Pstein128, Puffin,

R'n'B, RMCClassics, Rainbowflowerdoll, RashersTierney, Rd232, RekishiEJ, RexNL, Rjensen, Rjm at sleepers, Rjwilmsi, Rossami, SBaron, Saddhiyama, Sam Hocevar, Samsara,

SamuelTheGhost, Sandstein, Sannse, Scoo, Shleep, Skywriter, Spellmaster, Squiddy, StAnselm, Stbalbach, SteveMcCluskey, SteveStrummer, Storm Rider, SusikMkr, Synchronism, TAMilo,

Tabletop, Tacitus XIV, Taekwak, Taksen, TallulahBelle, Tamara O'brien, Tanr, TarseeRota, Tassedethe, Techfast50, The Wonky Gnome, The ed17, Thecheesykid, Themightyquill,

Thomasettaei, Tom harrison, Tony Sidaway, Tpbradbury, TyA, Unyoyega, Uppland, Valerius Tygart, Vapour, Vilnikis, Virago250, Vkyrt, Vssun, Wayiran, Wetman, Wgreason, Wittylama,

Wmahan, Woohookitty, Xanchester, Xavier Bell, Xiaphias, Yamara, Zetawoof, Zetowolf, Zoe, Zora, 392 anonymous edits

Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors

File:Jacob de Wit - Allegorie op het schrijven van de geschiedenis 1754.jpg Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Jacob_de_Wit_-_Allegorie_op_het_schrijven_van_de_geschiedenis_1754.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Bukk, Jan Arkesteijn, Lna,

Mattes, Picasdre, Vincent Steenberg

File:Thucydides Manuscript.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Thucydides_Manuscript.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: G.dallorto, Vercingetorix,

,

File:Shiji.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Shiji.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: FreCha, Guss

Image:Beda Petersburgiensis f3v.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Beda_Petersburgiensis_f3v.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Dsmdgold, GDK, Warburg

Image:Ibn Khaldoun.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Ibn_Khaldoun.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: G.dallorto, Maksim, Moumou82, 1 anonymous edits

License

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

//creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hist 1 Readings in Philippine History Module PDFDocument92 paginiHist 1 Readings in Philippine History Module PDFalex87% (82)

- Chapter I Intro To The Study and Writing HistoryDocument15 paginiChapter I Intro To The Study and Writing HistoryJahn Amiel DCruz100% (1)

- History-Scope and DefinitionDocument7 paginiHistory-Scope and Definitionswamy_me75% (4)

- History & ArchaeologyDocument24 paginiHistory & Archaeologydanish_1985Încă nu există evaluări

- List of Military AlliancesDocument5 paginiList of Military Alliancesdobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- HistoriographyDocument14 paginiHistoriographyhamza.firatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greco Roman History TheoryDocument4 paginiGreco Roman History Theoryswamy_me100% (6)

- History of Ethiopia and The HornDocument24 paginiHistory of Ethiopia and The Hornfentaw melkieÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Transition From Feudalism To Capital PDFDocument9 paginiThe Transition From Feudalism To Capital PDFRohan Abhi ShivhareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tangible and Intangible Cultural HeritageDocument15 paginiTangible and Intangible Cultural HeritagebumchumsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scope and The Value of History - Study of HistoryDocument7 paginiScope and The Value of History - Study of Historyshiv161Încă nu există evaluări

- IMPERIALISMDocument3 paginiIMPERIALISMShahriar HasanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indianization Debate: Historiography and Debates On South East Asian Cultural FormationsDocument8 paginiIndianization Debate: Historiography and Debates On South East Asian Cultural FormationsSantosh Kumar MamgainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approach Types of HistoryDocument18 paginiApproach Types of HistoryAhmad Khalilul Hameedy NordinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economy and Administration of Mauryan EmpireDocument5 paginiEconomy and Administration of Mauryan EmpireMayukh NairÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of EthiopiaDocument10 paginiHistory of EthiopiaWorku DembalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historiography of Delhi SultanateDocument22 paginiHistoriography of Delhi SultanateKundanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revenue System and Agricultural Economy During The Sultanate PeriodDocument17 paginiRevenue System and Agricultural Economy During The Sultanate PeriodIshaan ZaveriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Archaeological Sources To Reconstruct Indian HistoryDocument3 paginiArchaeological Sources To Reconstruct Indian HistoryShruti JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- In General, What Is History?Document12 paginiIn General, What Is History?Vishal AnandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Medieval IndiaDocument19 paginiEarly Medieval IndiaIndianhoshi HoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- MilitarismDocument9 paginiMilitarismAnaya SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter One 1Document37 paginiChapter One 1Gerbeba JaletaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historiography Definitions Nature and SC PDFDocument6 paginiHistoriography Definitions Nature and SC PDFAbdullah sadiqÎncă nu există evaluări

- IGNOU S Indian History Part 1 Modern India 1857 1964Document548 paginiIGNOU S Indian History Part 1 Modern India 1857 1964noah0ark100% (2)

- Different Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMDocument8 paginiDifferent Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMAditya ChourasiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kingship TheoryDocument13 paginiKingship TheoryNirvan GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greater IndiaDocument20 paginiGreater IndiaDavidNewmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marathi and Persiona Source of Maratha HistoryDocument10 paginiMarathi and Persiona Source of Maratha HistoryAMIT K SINGHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhakti TraditionDocument30 paginiBhakti TraditionPradyumna BawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delhi Sultanate Administration and JusticeDocument14 paginiDelhi Sultanate Administration and Justiceanusid45100% (1)

- Early Medieval CoinageDocument9 paginiEarly Medieval Coinagesantosh kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delhi Through The Ages 1st Year in English AfcemkDocument34 paginiDelhi Through The Ages 1st Year in English Afcemkanushkac537Încă nu există evaluări

- 13th Century NobilityDocument7 pagini13th Century NobilityKrishnapriya D JÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1 - Commercial RevolutionDocument3 paginiLesson 1 - Commercial RevolutionIzuShiawase0% (1)

- Sources of Ancient Indian HistoryDocument8 paginiSources of Ancient Indian HistoryHassan AbidÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Arab Invasion of SindhDocument7 paginiThe Arab Invasion of SindhDharmendra PalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agricultural Production in 13th and 14th CenturiesDocument5 paginiAgricultural Production in 13th and 14th CenturiessmrithiÎncă nu există evaluări

- History DoneDocument14 paginiHistory DoneAbhishek KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ignou Course On The Most Populous Country in The WorldDocument14 paginiIgnou Course On The Most Populous Country in The WorldAmit100% (1)

- Pre-Axumite and Axumite CivilizationDocument1 paginăPre-Axumite and Axumite Civilizationdaniel50% (2)

- Politics of Globalisation QP 2019 - TutorialsDuniyaDocument5 paginiPolitics of Globalisation QP 2019 - TutorialsDuniyasatyam kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reviewed Work S What Is History PDFDocument10 paginiReviewed Work S What Is History PDFSamantha SimbayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Medieval IndiaDocument10 paginiEarly Medieval IndiaAdarsh jha100% (1)

- HISTORIOGRAPHIESDocument3 paginiHISTORIOGRAPHIESShruti JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mhi 04 Block 02Document54 paginiMhi 04 Block 02arjav jainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rise of IslamDocument22 paginiRise of IslamayushÎncă nu există evaluări

- Between The Mosque and The TempleDocument1 paginăBetween The Mosque and The TempleTauheed67% (3)

- Art and Architecture of Vijayanagara EmpireDocument4 paginiArt and Architecture of Vijayanagara Empireray mehtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mauryan Economy: ST ND RD THDocument4 paginiMauryan Economy: ST ND RD THRamita Udayashankar100% (4)

- Trade in Early Medieval IndiaDocument3 paginiTrade in Early Medieval IndiaAshim Sarkar100% (1)

- Bipan Chandra - Colonialism, Stages of Colonialism and The Colonial StateDocument16 paginiBipan Chandra - Colonialism, Stages of Colonialism and The Colonial StateBidisha SenGupta100% (1)

- Pinaki Chandra - RMW AssignmentDocument7 paginiPinaki Chandra - RMW AssignmentPinaki ChandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Portuguese Emigration To The EthioDocument31 paginiEarly Portuguese Emigration To The EthioDanny TedlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Firoz Shah Tughlaq's AdministrationDocument22 paginiFiroz Shah Tughlaq's AdministrationSarthak Jain0% (1)

- Chapter 10 Cliff Notes PDFDocument8 paginiChapter 10 Cliff Notes PDFAriel GoldbergÎncă nu există evaluări

- China's Path To Modernization NotesDocument30 paginiChina's Path To Modernization NotesAlicia Helena Cheang50% (2)

- Indian Feudalism Debate AutosavedDocument26 paginiIndian Feudalism Debate AutosavedRajiv Shambhu100% (1)

- Evaluate The Role and Contributions of Martin Luther King JR To The Making and Strengthening of The Civil Rights Movement.Document3 paginiEvaluate The Role and Contributions of Martin Luther King JR To The Making and Strengthening of The Civil Rights Movement.Alivia BanerjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine DisciplineDocument36 paginiPhilippine DisciplineMay Anne OberioÎncă nu există evaluări

- History FDocument25 paginiHistory FJoyce AlmiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History M1515Document6 paginiHistory M1515ama kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wa0004.Document9 paginiWa0004.a.sharma150704Încă nu există evaluări

- Who Is A ChristianDocument19 paginiWho Is A Christiandobojac73100% (1)

- BMW Welt Munich BrochureDocument19 paginiBMW Welt Munich Brochuredobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Wikipedia - Weimar RepublicDocument21 paginiWikipedia - Weimar Republicdobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Wikipedia - Nazi GermanyDocument31 paginiWikipedia - Nazi Germanydobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- AxiologyDocument2 paginiAxiologydobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- AxiologyDocument2 paginiAxiologydobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Social PhilosophyDocument5 paginiSocial Philosophydobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Outline of PhilosophyDocument11 paginiOutline of Philosophydobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- OntologyDocument7 paginiOntologydobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Outline of Performing ArtsDocument3 paginiOutline of Performing Artsdobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Aesthetics: PhilosophyDocument20 paginiAesthetics: Philosophydobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Social ScienceDocument18 paginiSocial Sciencedobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Timeline of The Introduction of Television in CountriesDocument10 paginiTimeline of The Introduction of Television in Countriesdobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Public AdministrationDocument12 paginiPublic Administrationdobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- The Story of Civilization: Series OutlineDocument15 paginiThe Story of Civilization: Series Outlinedobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- List of Performances and Events at Woodstock Festival: Friday, August 15Document9 paginiList of Performances and Events at Woodstock Festival: Friday, August 15dobojac73Încă nu există evaluări

- Department of Arts and Sciences Education GE8 - Course SyllabusDocument7 paginiDepartment of Arts and Sciences Education GE8 - Course SyllabusYheng Sisbreño LancianÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Studies in Central European Histories 49) by Gerhard A. Ritter, translated by Alex Skinner-German Refugee Historians and Friedrich Meinecke_ Letters and Documents, 1910–1977 (Studies in Central Europ.pdfDocument569 pagini(Studies in Central European Histories 49) by Gerhard A. Ritter, translated by Alex Skinner-German Refugee Historians and Friedrich Meinecke_ Letters and Documents, 1910–1977 (Studies in Central Europ.pdfAlexandra Dias Ferraz Tedesco100% (1)

- Hermeneutical Naïveté: Hans-Georg Gadamer and The Historiography of ScienceDocument15 paginiHermeneutical Naïveté: Hans-Georg Gadamer and The Historiography of ScienceC.J. SentellÎncă nu există evaluări

- m1 - l2 Ge Hist 101 Historiography - Readings 1 3Document19 paginim1 - l2 Ge Hist 101 Historiography - Readings 1 3Kaneki KenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rosenstone Historical FilmDocument9 paginiRosenstone Historical FilmRohini SreekumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is History? What Is Historiography?Document11 paginiWhat Is History? What Is Historiography?Jeff OrdinalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Program Guide 2015Document108 paginiFull Program Guide 2015code1neÎncă nu există evaluări

- Editorial Board: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Federal University of Minas Gerais)Document200 paginiEditorial Board: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Federal University of Minas Gerais)Marc JacquinetÎncă nu există evaluări

- MA Sem 1 To 4 Final 2021-22Document80 paginiMA Sem 1 To 4 Final 2021-22મૌલિક લેઉવાÎncă nu există evaluări

- Causes of The Collapse of The Soviet Union PDFDocument12 paginiCauses of The Collapse of The Soviet Union PDFparamjit100% (1)

- The Debate Between Postmodernism and Historiography: An Accounting Historian's ManifestoDocument15 paginiThe Debate Between Postmodernism and Historiography: An Accounting Historian's ManifestoTiago AlmeidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- David Cressy-England On Edge - Crisis and Revolution 1640-1642 (2006)Document463 paginiDavid Cressy-England On Edge - Crisis and Revolution 1640-1642 (2006)Andrés Cisneros Solari100% (3)

- History A Level Coursework AqaDocument8 paginiHistory A Level Coursework Aqaafiwhwlwx100% (2)

- Carl Dahlhaus, J. B. Robinson - Foundations of Music History-Cambridge University Press (1983) PDFDocument187 paginiCarl Dahlhaus, J. B. Robinson - Foundations of Music History-Cambridge University Press (1983) PDFCamilo ToroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vittorio Hösle-Forms of Truth and The Unity of Knowledge-University of Notre Dame Press (2014)Document366 paginiVittorio Hösle-Forms of Truth and The Unity of Knowledge-University of Notre Dame Press (2014)Deznan BogdanÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV Hayden WhiteDocument21 paginiCV Hayden WhiteAtila BayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social DarwinismDocument4 paginiSocial DarwinismWorku JegnieÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Oxford History of Historical Writing - Volume 3 - 1400-1800Document750 paginiThe Oxford History of Historical Writing - Volume 3 - 1400-1800Francisco Javier Paredes100% (1)

- Page - 1Document113 paginiPage - 1Read to Lead With Yousuf JalalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Docslide - Us - Sat October 2007 PDFDocument48 paginiDocslide - Us - Sat October 2007 PDFhienleminh91Încă nu există evaluări

- Readings in Philippine History M1Document19 paginiReadings in Philippine History M1daphne pejo50% (2)

- Revised History Common Course Final Handout 1012Document51 paginiRevised History Common Course Final Handout 1012Hindeya AbadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment: 1. What Is History? How Different From Historiography?Document2 paginiAssessment: 1. What Is History? How Different From Historiography?Stephen BacolÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSIT History SyllabusDocument15 paginiBSIT History SyllabusMemel Falcon GuiralÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding History and Historiography: Study Guide For Module No. 1Document4 paginiUnderstanding History and Historiography: Study Guide For Module No. 1Desiree MatabangÎncă nu există evaluări

- The New Concept of TraditionDocument14 paginiThe New Concept of Traditionfour threeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bauckham R. - The Eyewitnesses and The Gospel Traditions (JSHJ 2003)Document34 paginiBauckham R. - The Eyewitnesses and The Gospel Traditions (JSHJ 2003)edlserna100% (2)

- 1003010491Document112 pagini1003010491indraÎncă nu există evaluări