Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Yates - Literature Review Final

Încărcat de

api-291421761Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Yates - Literature Review Final

Încărcat de

api-291421761Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Running Head: EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

Effects of Age of Autism Diagnosis: How Age of Intervention Affects Outcomes

Heather Yates

HDFS 5110

The University of Georgia

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

INTRODUCTION

Autism is a disorder that is relatively new, and as such, research has continually built

upon itself to better understand the disorder, predict outcomes of autistic children, and

maximizes positive outcomes (Hertz-Picciotto & Delwiche 2009). Autism is defined as a

complex developmental disability that typically appears during the first three years of life.

Autism is the result of a neurological disorder that affects the normal functioning of the brain,

impacting development in the areas of social interaction and communication skills (Autism

Society, n.p.). With the recent discovery of autism only 70 years ago, one of the first known

studies of children with autism was performed by Leo Kanner, who observed the behaviors of a

small group of children, that he termed early infantile autism, the word autism being derived

from the Greek root autos, meaning self (Wing, 1997, n.p.).

Since the incidence of autism has existed for centuries, but the concept of autistic

disorder is relatively new, the treatment of the condition has changed drastically over time

(Wing, 1997). For example, in the 16th century, Martin Luther accused a boy, showing severe

symptoms of autism, of having no soul, because he was possessed by the devil. In the 20th

century, autism has received more attention, particularly around theories of development and the

existence of autism. Many of these early theories, including one that proposed that autism results

from detached and cold parents, are considered false today (Wing, 1997).

Autism was also thought to be one of the earliest forms of schizophrenia, and the two

were paired together in a journal about early research of autism called The Journal of Autism and

Childhood Schizophrenia (DeMeyer, 1974; Wing, 1997). Extensive research performed in the

1990s shaped modern beliefs about autism and debunked previous theories, making it clear that

autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder, involving basic cognitive deficits, with genetic factors

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

predominantly strong in etiology (Rutter, 1996, p. 257). These studies further disproved the

earlier schools of thought around parental attachment and schizophrenia as causes of autism.

Currently, the prevalence of autism is on the rise, without showing signs of plateauing

(Hertz-Picciotto & Delwiche 2009). In California alone, the incidence of autism of rose

consistently from 6.2 for 1990 births to 42.5 for 2001 births for child age 5 per 1,000 births

(Hertz-Picciotto & Delwiche 2009). Based on statistics from the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention, the prevalence of autism nationwide has doubled from 1 of 125 births in 2004 to

an estimated 1 in 68 births in 2014 (Autism Society). Since there is no cure and no concrete

knowledge about the cause of autism, continuing research is imperative in finding evidencebased practices to treat the symptoms of autism.

Since autism was not recognized until the mid-20th century, the research has quickly built

on itself and continued to make improvements in treating symptoms associated with autism.

Treatment options include medication and a multitude of therapy and intervention options

(Autism Speaks). One of the most popular methods of treatment, is a behavioral approach, which

has been successful in increasing language, social, play, and academic skills, as well as in

reducing some of the severe behavioral problems often associated with the disorder

(Schreibman, 2000, p. 373). Typically, the behavioral approach is conducted in a school,

professional institution, or home, multiple days per week. Behavioral therapy has been shown to

be effective in improving behavior and social skills of children with autism, as demonstrated by

multiple studies in this literature review, such as Fenske (1975), Granpeesheh and colleagues

(2009), and Bauminger (2002).

This literature review will explore the use of early behavioral intervention treatment, and

how it affects the outcomes of children on the autistic spectrum. The review will take into

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

account the methods of the interventions, the intensity of the intervention, the age of the

participants at the time of the study, and the outcomes of the children after the study.

BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

Behavioral interventions are used to modify unwanted behaviors in autistic children and

are aimed at reducing the general level of impairment in autism (Ben-Itchak & Zachor, 2007,

p. 288). The theoretical infrastructure of behavioral intervention is founded in psychological

principles of learning human behavior (Schreibman, 2000, p. 373), which allows the

development of applications to alter behaviors. Behavioral interventions, also know as behavior

modification or applied behavior analysis (Ben-Itchak & Zachor, 2007), of autism aims to

eliminate or minimize the symptoms of autism, such as impaired communication skills, and

teach appropriate behaviors to children with autism to maximize positive outcomes in their

education and other environments (Schreibman, 2000). Examples of development that reduce

autism symptoms include: significant IQ gains, significant language gains, and improved social

behavior (Rogers, 1996). Although different behavioral interventions incorporate a range of

strategies like different curricula, settings, and methods of measuring progress, they all have

similar goals of reducing the debilitating symptoms of autism (Rogers, 1996).

Researching interventions to combat symptoms of autism are relatively new. In the

1970s, researchers were trying to understand if measuring the intelligence of a child with autism

was possible and reliable (DeMeyer et al., 1974). Researchers needed to find a reliable method of

measuring autism intelligence before finding methods to increase intelligence and functioning in

children with autism. In 1974, DeMeyer published a study showing that the IQ of children with

autism was reliably measurable using the Cattell- Binet test and Vineland Social Maturity scale.

This study also proved that an autistic childs IQ was predictable for school placement and

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

severity of symptoms (DeMeyer, 1974). Since DeMeyers (1974) IQ and outcome study,

researchers have moved forward in researching intervention and outcomes of autistic children.

Research, extending DeMeyers (1974) work examine how early intervention compares to late

intervention and IQ level correlate, how early intervention and school placement correlate, how

intervention intensity and outcomes correlate with reducing symptoms of autism and improving

social, language, and communication skills in children with autism.

AGE AT INTERVENTION

Following DeMeyers (1974) study, Fenske and collegues (1985) published a study that

hypothesized that autistic children who began behavioral intervention at an earlier age would

have a more positive outcome (p. 51) in school and functioning that children who began

intervention at a later age. The research conceptualizes positive outcome as living at home and

being enrolled in school full-time (Fenske et al., 1975) For this study, 18 children were placed in

an educational and treatment program at the Princeton Child Development Institute for five days

a week for 11 months (Fenske et al., 1985). Group 1 consisted of 9 children who entered the

program before the age of 60 months, and Group 2 entered the program after the age of 60

months (Fenske et al., 1985). The results show that 6 of 9 (67%) children who began the program

before age 60 months achieved positive outcome (Fenske et al., 1985). In Group 2, 1 out of 9 of

the children achieved the positive outcome of being placed in a public school, in a regular

classroom or in a special education classroom (Fenske et al., 1985). Therefore, Fenske and

colleagues (1985) study, although small scale, supports that early intervention is beneficial to

children with autism.

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT HOURS

A more recent study investigated behavioral treatment of autistic children between the

ages of 2 and 7 years of age, and measured how intensity of treatment (hours being treated) and

the age correlated with the number of behavioral objectives that the child mastered (Granpeesheh

et al., 2009). While Fenske and colleagues (1985) study focused on attaining the outcome of

being enrolled full time in public school classroom, Granpeesheh and colleagues (2009) study

focused on minimizing autism symptoms through the children attaining behavioral goals. The

results of the study showed a linear relationship between the childs age and treatment hours,

meaning an increase in treatment hours and a decrease in child age predicted an increase in the

number of mastered behavioral objectives (Granpeesheh et al., 2009, p. 1019). The age group

consisting of children age 7-12 years showed little difference in improvements based on the

number of hours the were treated (Granpeesheh et al., 2009). Therefore, similar to Fenskes

(1985) study, Granpeesheh and colleagues (2009) study demonstrated that treating autism using

behavioral intervention at an early age is more beneficial than treating it at later ages. This study

also demonstrated that early intervention plus intense, extensive treatment are optimal for

children with autism (Granpeesheh et al., 2009).

LATE INTERVENTION

The previous studies show that early intervention is more beneficial to child outcomes

than later intervention. This does not mean that late intervention is ineffective. A study was

performed in 2002 to test the effectiveness of a cognitive behavior intervention on autistic

children, ages 8 to 17, who are considered high functioning (Bauminger). The behavioral

intervention aimed to pinpoint social skills, such as emotional understanding and problem

solving skills. Baumingers (2002) research concluded that the cognitive behavioral intervention

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

correlated with an improvement in social skills, emotional understanding, and problem solving

skills. The study states that overall the group showed improvements and does not mention

discrepancies between the younger participants and the older participants in the study. Therefore,

this study supports that behavioral intervention in late childhood and adolescence, despite

findings by Fenske and collegaues (1985) and Granpeesheh and colleagues (2009) who argue

that early intervention is the most effective route (Bauminger, 2002).

PLACEMENT PREDICTABILITY

As previously mentioned, DeMeyers (1974) study tested the reliability of testing the

intelligence of children with autism, and used IQ to measure predictability of schooling

placement. Harris and Handleman (2000) aimed to continue DeMeyers (1974) research by

studying the effect of early intervention and IQ on the predictability of placement in school.

After the children participated in a preschool behavioral intervention program, the researchers

followed up four to six years later to evaluate the correlation between age at intervention and IQ

and a childs placement in school (Harris & Handleman, 2000). The study showed that all of the

children, but one, who entered the program before the age of 45 months were placed in regular,

public school classrooms (Harris & Handleman, 2000). Fourteen out of fifteen children who

entered the program after 50 months of age were placed in special education classrooms (Harris

& Handleman, 2000). Eleven out of fourteen children that had an IQ of 80 or higher were

included in regular classrooms (Harris & Handleman, 2000). All 13 children with an IQ of 76

and lower were placed in a special education classroom (Harris & Handleman, 2000). Although

the IQ of most children in the study increased after discharge from the study, the children who

entered the program at a younger age demonstrated a larger increase in IQ (Harris & Handleman,

2000). This study and DeMeyers (1974) study illustrate that a childs IQ is a large factor in a

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

childs school placement and outcomes. Harris and Handlemans (2000) study builds on

DeMeyers (1974) research to support using IQ, as a prediction for school placement, and

supports early intervention to aid in IQ development and attaining positive outcomes.

IQ AND TREATMENT INTENSITY

As mentioned by Granpeesheh and colleagues (2009) in The Effects of Age and

Treatment Intensity on Behavioral Intervention Outcomes for Children with Autism Spectrum

Disorders, there are few studies about intensity of behavioral treatment on treatment outcomes.

According to Granpeesheh and colleagues, treatment intensity is measured by the numbers of

hours of treatment per week (2009). Granpeesheh (2009) mentions that the only other study of

treatment intensity was performed by Lovaas in 1987. A group of four year olds with autism

were treated with a behavioral intervention program with the goal of helping some of the young

autistic children in the study in attaining a similar level of learning as their peers by first grade

(Lovaas, 1987). The experimental group of children received intense treatment that took place

for 40 hours per week and the control group received a minimal treatment of 10 hours or less per

week (Lovaas, 1987). The results illustrated that 47% of the children receiving the intense 40

hour treatment achieved normal intellectual and educational functioning, with normal-range IQ

scores and successful first grade performance in public schools (Lovaas, 1987) On the other

hand, in the control group, only 2% of the children (n=40) achieved normal educational and

intellectual functioning (Lovaas, 1987). Although less than half of the children (47%) from the

experimental group attained a similar learning level to their peers, the outcome for the

experimental group was stronger than the control group (2%) (Lovaas, 1987). This shows that

among autistic children of the same age, intense treatment with a high number of hours per week

correlates can be more effective than less hours of treatment (Lovaas, 1987). As mentioned

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

above in the comparison of late intervention and early intervention, Granpeesheh and colleagues

(2009) investigates how treatment hours differ between a group of younger children, and a group

of older children participating in the intervention. Granpeeshehs (2009) study demonstrates how

research on autism and behavioral intervention has built upon itself and expanded within the last

fifty years. Lovaas (1987) research laid the infrastructure for research examining intervention

intensity, and Granpeesheh and colleagues (2009) extended the research, by adding the variable

of age to the effects of treatment intensity.

DISCUSSION, IMPLICATIONS, AND CONCLUSION

The studies reviewed in this paper indicate the progress being made in the field of autism

research. The earliest study reviewed in this paper question the testability of an autistic childs IQ

in DeMeyer and collegues (1974) study to researching the implications of treatment intensity on

the mastery of behavioral goals and decreasing symptoms of autism in Granpeesheh and

collegues (2009) study. When questioning the implications of these studies, it is important to

review the reliability and generalizability of the studies. Most of the researchers, such as Fenske

(1985), Granspeesheh (2009), Harris and Handleman (2000), and Lovaas (1987) support

beginning behavioral intervention of autism at an early age. When considering the

generalizability of the studies, it is important to consider the sample size. Fenskes (1985) study

included 18 participants. This sample is not representative of the number of children along the

autistic spectrum. But, Granpeeshehs study included 245 children with autism, which can

increase the generalizability of the findings to the population of children with autism (2009).

Baumingers study defies studies that support the detrimental effects of behavioral intervention

after early childhood, but only includes 15 participants (2002). Being a small-scale study and one

of few studies of adolescent intervention, the findings are unreliable and not generalizable

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

10

enough to compete against the support of behavioral intervention in early childhood. Also,

although some studies support starting behavioral intervention at an early age, the results are not

overwhelmingly positive. In Fenskes study, 66% of the children who received treatment before

age 5 achieved the positive outcome of being enrolled full time in a public school (1985). This

can bring into question whether such an early intervention truly makes the difference. Therefore,

more studies and larger scale studies should be performed about early intervention to investigate

the effectiveness and reliability of early intervention.

Each study that I reviewed consisted of quantitative research that focused on statistical

outcomes of intervention and number of children who achieved the researchers concept of

positive outcomes. Although the studies are small scale, like Fenskes (1985) and Baumingers

(2002), the information is collected through quantitative methods. I think it is necessary to

compose more qualitative studies about autism intervention, such as interviewing the autistic

children who received treatment. It is important to understand how the child feels about their

progress, outcomes, and opinions of the treatment, or even interviewing a family about how the

treatment has affected interactions with their child. A mixed methods approach would be useful

for researchers interested in investigating the effectiveness of a behavioral intervention treatment

program and are also interested in the childs opinions and feelings about the treatment and their

personal outcomes. The research of autism has covered much ground in the short time that

autism has been researched, but research must be continued and expanded. Researchers should

continue to broaden the field of studies pertaining to autism, including expanding to larger scale

studies and using qualitative and mixed methods approaches to gain optimal data about the

participants.

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

11

From being coined a devil possession and childhood schizophrenia to being defined as

it is today: a neurodevelopmental disorder, researchers have gained extensive knowledge about

the implications, symptoms, and outcomes of autism spectrum disorder (Wing, 1997). Autism,

treatment, and effects are becoming increasingly researched with the rising prevalence of autism.

Studies, such as the research reviewed in this paper, tend to emphasize the importance of

behavioral intervention at an early age. Factors to be noted, along with the importance of early

age, include a childs IQ and intensity of treatment. These factors play into the effects of

behavioral treatment, which increase language, social, play, and academic skills (Schreibman,

2000, p. 373) and reducing the common symptoms associated with autism. Behavioral methods

and interventions are one of the most popular treatments of autism spectrum disorders, so it is

important to continue research about how to tailor intervention methods to be most beneficial to

children with autism.

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

12

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

13

REFERENCES

About Autism | Autism Society. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.autism- society.org/what-is/

Bauminger, N. (2002). The facilitation of social-emotional understanding and social

interaction in high-functioning children with autism: intervention outcomes.

Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 32(4), 283-298.

Ben-Itzchak, E., & Zachor, D. (2007). The effects of intellectual functioning and autism

severity on outcome of early behavioral intervention for children with autism.

Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28(3), 287-303

DeMeyer, M., Barton, S., Alpern, G., Kimberlin, C., Allen, J., Yang, E., & Steele, R.

(1974). The measured intelligence of autistic children. The Journal of Autism and

Childhood Schizophrenia, 4(1), 42-60.

Fenske, E., Zalenski, S., Krantz, P., & McClannahan, L. (1985). Age at intervention and

treatment outcome for autistic children in a comprehensive intervention program.

Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 5(1-2), 49-58. Retrieved

from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0270468485800057

Granpeesheh, D., Dixon, D., Tarbox, J., Kaplan, A., & Wilke, A. (2009). The effects of age and

treatment intensity on behavioral intervention outcomes for children with autism

spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(4), 1014-1022. Retrieved

from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1750946709000658

Harris, S., & Handleman, J. (2000). Age and IQ at intake as predictors of placement for young

children with autism: a four- to six-year follow-up. Journal of Autism and Developmental

Disorders, 30(2), 137-142. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

EFFECTS OF AGE OF AUTISM DIAGNOSIS

14

Hertz-Picciotto, I., & Delwiche, L. (2009). The rise in autism and the role of age at

diagnosis. Epidemiology, 20(1), 84-90. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4113600/

Lovaas, O. (1987). Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in

autistic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(1), 3-9. Retrieved

from EBSCOhost.

Rutter, M. (1996). Autism research: prospect and priorities. Journal of Autism &

Developmental Disorders., 26(2), 257-275. Retrieved from

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02172023

Schreibman, L. (2000). Intensive behavioral/psychoeducational treatments for autism:

Research needs and future directions. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders.,

30(5), 373-378. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

Wing, L. (1997). The history of ideas On autism: Legends, myths And reality. Autism, 13-23.

Retrieved from http://compasstraining.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/9/6/13963732/wing_1997.pdf

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Business Policy FormulationDocument21 paginiBusiness Policy FormulationWachee Mbugua50% (2)

- Proposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Document6 paginiProposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Foster Boateng67% (3)

- Ujpited ?tate of Americal: PresidentsDocument53 paginiUjpited ?tate of Americal: PresidentsTino Acebal100% (1)

- Health EconomicsDocument114 paginiHealth EconomicsGeneva Ruz BinuyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biodiversity Classification GuideDocument32 paginiBiodiversity Classification GuideSasikumar Kovalan100% (3)

- Ashforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The OrganizationDocument21 paginiAshforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The Organizationhoorie100% (1)

- The ADDIE Instructional Design ModelDocument2 paginiThe ADDIE Instructional Design ModelChristopher Pappas100% (1)

- Second Periodic Test - 2018-2019Document21 paginiSecond Periodic Test - 2018-2019JUVELYN BELLITAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ass 3 MGT206 11.9.2020Document2 paginiAss 3 MGT206 11.9.2020Ashiqur RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Great Idea of Brook TaylorDocument7 paginiThe Great Idea of Brook TaylorGeorge Mpantes mathematics teacherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1-PRELIM: Southern Baptist College M'lang, CotabatoDocument11 paginiModule 1-PRELIM: Southern Baptist College M'lang, CotabatoVen TvÎncă nu există evaluări

- ReportDocument7 paginiReportapi-482961632Încă nu există evaluări

- Review Unit 10 Test CHP 17Document13 paginiReview Unit 10 Test CHP 17TechnoKittyKittyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multiple Choice Test - 66253Document2 paginiMultiple Choice Test - 66253mvjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 6. TNCTDocument32 paginiLesson 6. TNCTEsther EdaniolÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV Jan 2015 SDocument4 paginiCV Jan 2015 Sapi-276142935Încă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Practices and Academic Performance of Blaan Pupils in Sinapulan Elementary SchoolDocument15 paginiCultural Practices and Academic Performance of Blaan Pupils in Sinapulan Elementary SchoolLorÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Titles List 2014, Issue 1Document52 paginiNew Titles List 2014, Issue 1Worldwide Books CorporationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enterprise Information Management (EIM) : by Katlego LeballoDocument9 paginiEnterprise Information Management (EIM) : by Katlego LeballoKatlego LeballoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 in Oral Com 1Document20 paginiModule 3 in Oral Com 1Trisha DiohenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Commonlit Bloody KansasDocument8 paginiCommonlit Bloody Kansasapi-506044294Încă nu există evaluări

- Wound Healing (BOOK 71P)Document71 paginiWound Healing (BOOK 71P)Ahmed KhairyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pengaruh Implementasi Sistem Irigasi Big Gun Sprinkler Dan Bahan Organik Terhadap Kelengasan Tanah Dan Produksi Jagung Di Lahan KeringDocument10 paginiPengaruh Implementasi Sistem Irigasi Big Gun Sprinkler Dan Bahan Organik Terhadap Kelengasan Tanah Dan Produksi Jagung Di Lahan KeringDonny Nugroho KalbuadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Management and OrganisationDocument34 paginiChapter 1 Introduction To Management and Organisationsahil malhotraÎncă nu există evaluări

- CvSU Vision and MissionDocument2 paginiCvSU Vision and MissionJoshua LagonoyÎncă nu există evaluări

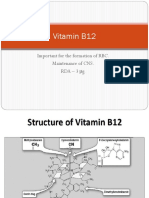

- Vitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceDocument19 paginiVitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceHari PrasathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challengue 2 Simpe P.P TenseDocument7 paginiChallengue 2 Simpe P.P TenseAngel AngelÎncă nu există evaluări

- IS-LM Model Analysis of Monetary and Fiscal PolicyDocument23 paginiIS-LM Model Analysis of Monetary and Fiscal PolicyFatima mirzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dmat ReportDocument130 paginiDmat ReportparasarawgiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Us Aers Roadmap Noncontrolling Interest 2019 PDFDocument194 paginiUs Aers Roadmap Noncontrolling Interest 2019 PDFUlii PntÎncă nu există evaluări