Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Haymarket Square Riot TTTT

Încărcat de

api-270974388Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Haymarket Square Riot TTTT

Încărcat de

api-270974388Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Haymarket Square

Riot

It was evening, May 4, 1886. In

Chicagos

Haymarket Square, two or three

thousand

workers had gathered. They listened

as

speakers protested police shootings at

a riot

at the McCormick Harvester plant the

day before.

The last Haymarket speaker was just

finishing

up. Only a few hundred people

remained when

police on horseback moved in and

ordered

everyone to leave. Suddenly, someone

threw

a bomb. It exploded. Police began

shooting.

People screamed and fled. Seven

policemen and

at least four workers died. An eighth

policeman

died of his wounds much later.

Long before 1886, Chicago had

become a

tense, deeply divided city. After the

Civil War,

it grew rapidly, even uncontrollably.

Tens of

thousands of workers labored long

hours for low

pay in its factories, warehouses, and

stockyards.

A huge demand for laborers made

Chicago a

magnet pulling in immigrants from

Germany,

Ireland, Poland, Italy, and many other

nations. As

they struggled to find their way in a

strange land,

they often met with suspicion and

hostility. Many

native-born Chicagoans saw these

immigrants

as a threat to social order and a more

traditional

way of life.

Struggles to organize unions often

brought

these tensions to the surface. Powerful

business

owners fought bitterly to keep the

unions out. In

the 1870s and 80s, several strikes led

to riots

and violent clashes between the police

and the

workers. The Haymarket bombing

itself took place

at the high point of a national

movement for the

eight-hour workday. The Chicago

newspapers

generally backed the owners in such

labor

battles. The press often depicted union

organizers

as dangerous, foreign-born radicals

who were

merely using the workers to bring

about a violent

socialist revolution.

Clerks, professionals, small business

owners,

and other middle-class Chicagoans

knew little

about the radical ideas brought to

Chicago by

German or other foreign-born

socialists and

anarchists. What they did know was

that these

radicals always seemed to be stirring

up trouble

among the citys workers.

Their fears were not entirely

unreasonable.

Some radicals, foreign and nativeborn, did

call for revolution. And at times, they

did

seem to glorify the use of violence to

bring

it about. In anarchist newspapers such

as

the German Arbeiter-Zeitung or the

English

language paper The Alarm, some

writers seemed

almost glowing in their view that

dynamite could

be the great equalizer in the war

between the

bosses and the workers.

Following the Haymarket bombing,

terrified

Chicagoans directed their rage at the

anarchist leaders of the Haymarket

protest.

Eight of those leaders were convicted

of

inciting the violence, even though

none were

linked to the bomb or the bomb

thrower.

Four were hung. One committed

suicide.

Most historians agree that the

Haymarket

trial was deeply flawed. Witnesses

were

highly unreliable. The judge was

openly hostile

to the defendants. Only people already

suspicious of the anarchists were

allowed on

the jury. In 1893, after tempers had

cooled

somewhat, a reform-minded governor

pardoned the remaining three

Haymarket

defendants still in jail.

From the four documents provided

here, you

will NOT be able to decide the

innocence

or guilt of the anarchists on trial.

Instead,

these documents will help you

understand

the ideas of the anarchists and the

views of

their critics. Your task is not to act as a

jury

in what was clearly an unjust trial.

Instead,

it is to understand the radicalism of

the late

1800s and the views of those opposed

to it.

The documents should help you

debate the

larger meaning of Haymarket to

Chicago and the

nation at that time.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Section 1 Anticipation GuideDocument5 paginiSection 1 Anticipation Guideapi-270974388Încă nu există evaluări

- 1 (14 Points) : Directions List The Answers To The Following QuestionsDocument2 pagini1 (14 Points) : Directions List The Answers To The Following Questionsapi-270974388Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 5 Packet AnswersDocument3 paginiChapter 5 Packet Answersapi-270974388Încă nu există evaluări

- Progressive ReviewDocument2 paginiProgressive Reviewapi-270974388Încă nu există evaluări

- The New Colossus Poem AnalysisDocument2 paginiThe New Colossus Poem Analysisapi-270974388Încă nu există evaluări

- Albert Parsons Lesson Plan-2Document11 paginiAlbert Parsons Lesson Plan-2api-270974388Încă nu există evaluări

- Document What I Learned For 3Document2 paginiDocument What I Learned For 3api-270974388Încă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Realism of Hans MorgenthauDocument94 paginiThe Realism of Hans MorgenthauFabricio Brugnago0% (1)

- Property Tax Regimes in East AfricaDocument58 paginiProperty Tax Regimes in East AfricaUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)Încă nu există evaluări

- PAtton Leadership PrincipleDocument1 paginăPAtton Leadership PrincipleKwai Hoe ChongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blur MagazineDocument44 paginiBlur MagazineMatt CarlsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergence of Trade UnionismDocument40 paginiEmergence of Trade Unionismguruprasadmbahr7267Încă nu există evaluări

- Republic vs. OrbecidoDocument3 paginiRepublic vs. OrbecidoMaria Jela MoranÎncă nu există evaluări

- MY Current Affairs NotesDocument127 paginiMY Current Affairs NotesShahimulk Khattak100% (2)

- Administrative LiteracyDocument87 paginiAdministrative LiteracyPoonamÎncă nu există evaluări

- PIL ReviewerDocument23 paginiPIL ReviewerRC BoehlerÎncă nu există evaluări

- World Migration Report IOM 2020Document498 paginiWorld Migration Report IOM 2020KnowledgehowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Woodfin Police Chief's Letter To Buncombe CommissionersDocument2 paginiWoodfin Police Chief's Letter To Buncombe CommissionersJennifer BowmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Real-World Economics ReviewDocument182 paginiReal-World Economics Reviewadvanced91Încă nu există evaluări

- Test Bank For Business in Action 8th Edition by Bovee IBSN 978013478740Document15 paginiTest Bank For Business in Action 8th Edition by Bovee IBSN 978013478740Jack201100% (4)

- Dissenting Opinion of Justice Puno in Tolentino v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 148334Document37 paginiDissenting Opinion of Justice Puno in Tolentino v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 148334newin12Încă nu există evaluări

- Listado de Paqueteria de Aduana Fardos Postales PDFDocument555 paginiListado de Paqueteria de Aduana Fardos Postales PDFyeitek100% (1)

- RTA CreationDocument3 paginiRTA CreationErnesto NeriÎncă nu există evaluări

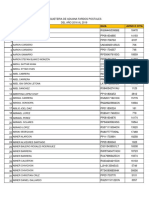

- 3 Years GENERAL POINT AVERAGE GPA PER CORE SUBJECT BY SCHOOLDocument143 pagini3 Years GENERAL POINT AVERAGE GPA PER CORE SUBJECT BY SCHOOLRogen VigilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aft BenifitsDocument26 paginiAft BenifitsStuddy StuddÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philips Malaysia Author Is Ed Service CentreDocument7 paginiPhilips Malaysia Author Is Ed Service CentrerizqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feminist Interpretations of Emmanuel LevinasDocument289 paginiFeminist Interpretations of Emmanuel LevinasMaría ChávezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 911 and The IntelligentsiaDocument143 pagini911 and The IntelligentsiaKristofer GriffinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction of Things Fall ApartDocument16 paginiIntroduction of Things Fall AparthassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Generational Differences Chart Updated 2019Document22 paginiGenerational Differences Chart Updated 2019barukiÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSS-Essay Paper 2006Document1 paginăCSS-Essay Paper 2006Raza WazirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kapisanan v. Yard Crew (1960)Document2 paginiKapisanan v. Yard Crew (1960)Nap GonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elizabeth I SummaryDocument1 paginăElizabeth I SummaryNataliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Database Tours N TravelsDocument172 paginiDatabase Tours N TravelsDrishti Anju Asrani ChhabriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Political Salience of Cultural Difference. Why Chewas and Tumbukas Are Allies in Zambia and Adversaries in MalawiDocument17 paginiThe Political Salience of Cultural Difference. Why Chewas and Tumbukas Are Allies in Zambia and Adversaries in MalawiINTERNACIONALISTAÎncă nu există evaluări

- BPS95 07Document93 paginiBPS95 07AUNGPSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To The Study of GlobalizationDocument32 paginiIntroduction To The Study of GlobalizationHoney Kareen50% (2)