Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Grey Et Al-2007-Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities

Încărcat de

api-302158049Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Grey Et Al-2007-Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities

Încărcat de

api-302158049Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2007, 20, 615

Service User Outcomes of Staff Training in

Positive Behaviour Support Using

Person-Focused Training: A Control Group

Study

Ian M. Grey* and Brian McClean

*KARE Services, Newbridge, Co., Kildare, Ireland, School of Psychology, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, Brothers of Charity,

Roscommon, Ireland

Accepted for publication

19 June 2006

Background Effectively supporting individuals with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviours

continues to be a priority for service providers. Personfocused training (PFT) is a model of service delivery

which provides staff with skills in functional assessment

and intervention development. Existing longitudinal

data from a study of 138 cases suggest that implementation of staff-developed behaviour support plans through

PFT is effective in reducing challenging behaviour in

approximately 77% of cases [McClean et al. Journal of

Intellectual Disability Research (2005) vol. 49, pp. 340353].

However, no control group was used in this study.

Method The current study involves the use of a control

group of individuals with challenging behaviours

matched against those selected for PFT over a 6-month

period. Groups were matched on type of challenging

behaviour, duration of challenging behaviour, gender

and level of disability. Information on the frequency,

management difficulty and severity of challenging beha-

Introduction

The detrimental effects of challenging behaviour among

people with intellectual disabilities are well known.

Behaviours such as physical aggression, self-injury or

property destruction can threaten an individuals residential placement (Bruininks et al. 1988), interfere with

opportunities for social interaction (Anderson et al. 1992)

and community participation (Larson 1991). Indeed

challenging behaviours are most commonly defined in

terms of their capacity to impede access to or enjoyment

of community facilities (Emerson & Emerson 1987).

Unfortunately, there are relatively few studies which

2007 BILD Publications

viour was collected pre- and post-training using the

Checklist of Challenging Behaviours (CCB) for both

groups. Observational data were collected for the target

group alone. Rates of psychotropic medication were

tracked across the training period.

Results Significant reductions in the frequency, management difficulty and severity of challenging behaviour

were found for service users in the target group but not

in the control group after 6 months. No significant changes were found in the use of psychotropic medication

for either group over the 6-month period.

Conclusion Overall results suggest that PFT is an effective model for providing support to individuals with

challenging behaviours.

Keywords: challenging behaviour, positive behaviour

support, applied behaviour analysis, control group, service delivery, psychotropic medication

provide accurate information on the prevalence rates of

challenging behaviours. In the UK, prevalence rates of

approximately 8% have been reported (Emerson &

Bromley 1995) while in the Republic of Ireland, rates as

high as 28% have been recorded (McClean & Walsh

1995a,b) although such discrepancy is most probably

attributable to varying definitions of challenging behaviour. Consequently, services are frequently presented

with the question of how to effectively support individuals who display such behaviour. Despite a large body

of empirical work in the area, data suggest that services

continue to struggle with this question. In a study of

265 individuals with challenging behaviour, Robertson

10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00335.x

Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 7

et al. (2005) identified that only 15% had a written behaviourally orientated treatment programme and, of these,

many were simplistic. Furthermore, in a Canadian sample of 625 adults and children with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviours, Feldman et al. (2004)

found that 97% of individuals were receiving some form

of intervention but that the majority of these were informal (55%) (i.e. simplistic, poorly recorded and typically

not evaluated). Such data would suggest that many

individuals with intellectual disabilities are not in

receipt of therapeutic interventions for challenging

behaviours drawn from an established evidence-base.

Pharmacological and behavioural interventions represent the dominant intervention approaches currently

available in the area of challenging behaviour (Grey &

Hastings 2005). Research to date has consistently

reported that many individuals with challenging behaviour are in receipt of psychotropic medication. One

rationale for such treatment is based upon the premise

that challenging behaviours may represent an atypical

manifestation of a psychiatric disorder. However, there

is a wide variation in the frequency of psychotropic

medication usage to reduce the occurrence of challenging behaviours with rates as high as 61% reported in

some groups (Harper & Wadsworth 1993). Additionally,

the high prevalence rate of psychotropic medication is a

cause for concern given the lack of empirical data on

their effectiveness (McGillivray & McCabe 2004; Singh

et al. 2005).

Interventions drawn from applied behaviour analysis

can be effective in supporting individuals with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviours

(British Psychological Society, 2005). Reviews suggest

that behavioural interventions based upon the results of

functional assessments are effective in reducing the

occurrence of challenging behaviour (Carr et al. 1999;

Grey & Hastings 2005; McClean et al. 2005). Hence it is

no longer the task of practitioners in the field to demonstrate the efficacy of applied behaviour analysis, rather

the task now is one of effective dissemination (Emerson

2001).

However, this is not a task that has attracted as

much focus as it warrants. One reason for this may be

that many services have opted for the specialist team

model to deliver behavioural supports. In this model, a

small number of specialists with expert knowledge of

applied behaviour analysis conduct and deliver interventions (McClean & Halliday 1999). The primary difficulty confronting such teams is one of logistics

(Emerson & Forrest 1996). The number of specialists

required to meet the needs of people with challenging

behaviours may not be available (Sprague et al., 1996).

In a survey of 46 peripatetic teams, Emerson & Forrest

(1996) found that 49% of teams carried caseloads of

between one and six cases and that caseloads range

from 1 to 25. The authors report that only 48% of people with severe challenging behaviours were on current

team caseloads. There are simply not enough psychologists or other specialists to provide the service that

people with challenging behaviour need. Without adequate throughput, the specialist team may fail to provide the specialist support services required.

One of the most discussed developments in supporting individuals with challenging behaviour in recent

times has been that of positive behaviour support (PBS).

PBS is an approach to support derived from social, behavioural and biomedical science that is applied to achieve

reduction in challenging behaviours and improved quality of life (Knoster et al. 2003). The core elements of PBS

involve: (1) the use of comprehensive functional assessment involving all stakeholders and intervention agents

to achieve a contextual fit in typical service settings. This

typically entails that functional assessments are conducted in routine service settings, (2) altering deficient environmental conditions, (3) altering deficient behaviour

repertoires and (4) achieving lifestyle change through

multi-component behaviour support plans while

decreasing the frequency of challenging behaviour (Snell

et al. 2005). These elements revolve around the hub of

the PBS team which comprises all relevant stakeholders

using a collaborative rather than expert-driven approach.

One additional feature of PBS that is discussed less

frequently than those above is its approach to training.

Implicit within the model is that training does not follow

the trajectory where strategic information is simply

transferred from experts to service providers but is

rather as a process of mutual education carried out in

on-site settings rather than in the confines of universitybased locations (Carr et al. 2002).

To date, one large review of PBS has been conducted

(Carr et al. 1999). This review of outcomes associated

with PBS suggests that PBS is effective in reducing the

challenging behaviour in one-half to two-thirds of

cases. It also suggests that success rates almost double

when interventions are based upon a prior functional

assessment. Recent studies have examined the extent to

which PBS characteristics or processes such as functional assessment and stakeholder participation actually

occur in practice. Snell et al. (2005), using a sample of

111 studies over a 5-year period involving school-age

children with disabilities, identified that the involvement of intervention agents and the use of routine

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

8 Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities

settings were not a frequent characteristic of assessment processes employed. Multiple- versus single-component interventions were commonly reported but

typically involved a maximum of two or three interventions. Only two-thirds of studies reported the use

of antecedent procedures and only half reported teaching functionally equivalent skills as an intervention.

The conclusion reached by the authors is that the PBS

standards of using a comprehensive approach with a

focus on prevention through altering environmental

conditions and teaching functionally equivalent skills

are not extensive in current assessment-based research.

However, these findings may not be representative of

typical service settings as the majority of assessments

were conducted by researchers and belie an emphasis

on a minimal number of interventions to allow

research standard evaluation. Furthermore, this study

did not include any consideration of the role of training for primary care staff which Carr et al. (2002) identify as central to PBS. Attempts to define PBS typically

include its reliance on functional assessment, goal of

quality of life improvement and the use of multi-element interventions. An element of PBS is the involvement of staff in a manner that elevates them to a

central role rather than that of an information provider,

but how to successfully achieve this is rarely identified

in the literature. This may explain its absence as a

selection criterion in this most recent evaluation of PBS

practices.

One large services-based study of PBS is available

which clearly identifies a method of placing staff at the

very centre of the delivery of PBS. McClean et al. (2005)

have developed a method of delivering PBS through a

model called person-focused training (PFT). The model

involves training staff who work with service users displaying challenging behaviour to conduct a functional

assessment, to design and to implement a multi-element

behaviour support plan for this person. Assessment

includes a comprehensive psychosocial assessment,

incident analysis, functional assessment and hypothesis

testing. Intervention involves environmental accommodation, skills teaching, direct interventions and reactive

strategies. Implementation involves periodic service

review (LaVigna et al. 1994) and quarterly progress

reports. Such an approach meets the key standards of

PBS (e.g. multi-element interventions are developed

from functional assessments by the primary care staff

who are the also the primary intervention agents).

An analysis of longitudinal data from 138 staff-developed behaviour support plans indicated that significant

improvements were observed in 77% of cases (defined

as a reduction to below 30% of baseline rates of behaviour) and that at an average follow-up of 22 months

such improvements were maintained. Unfortunately,

there was no control group and hence it remains unclear

whether reductions in challenging behaviour would

have occurred over the same time period. However,

recent studies have identified that challenging behaviours remain chronic in the absence of appropriate

intervention and therefore it is unlikely that such

improvements would have occurred naturally (Stancliffe

et al. 1999; Watson et al. 2001; Thompson & Reid 2002).

The current study has as its primary goal to determine

whether training staff in the assessment of challenging

behaviour and the development of behaviour support

plans will result in reductions in challenging behaviour

for clients with whom they directly work (PFT). In addition to pre- and post-measures, a control group of clients

with broadly similar topographies and duration of challenging behaviour was also identified. The same measures were completed for this group at the same time

points as those for the training group. No staff training

took place for this group and no formal behavioural

assessments were conducted or behaviour support plans

derived from such assessments implemented during this

time. The selection of outcomes for service users as the

focus of interest departs from the majority of work in the

area of staff training in challenging behaviour. The

majority of research to date has evaluated staff training

with respect to staff outcomes such as attribution change

which may mediate staff behaviour with relatively little

work addressing staff behaviour or skills directly (Jahr

1998; Ager & OMay 2001). As such, the selection of service user outcomes lends considerable ecological validity

to the current study and informs us directly as to whether this model of service delivery has beneficial client

outcomes.

Method

Design

A non-randomized matched control group design was

used in this study. Participants were matched on topography of challenging behaviour, duration of challenging

behaviour and gender to reduce pre-treatment differences between groups.

Service users

The target group consisted of service users for

whom staff would complete the training course in

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 9

multi-element behaviour support over a 6-month period.

The target group was initially comprised of 37 clients

with challenging behaviours in two different service

locations. This figure was reduced to 30 by the end of

the training period.1 Two staff members did not complete the training because of leaving the service. The

remaining five individuals did not meet the criteria for

completion of the course and are not included here. The

control group of 30 service users consisted of clients also

identified by management as requiring input for challenging behaviour. Members of the control group were

drawn from the same service locations as the target

group. All members of both groups were from the same

ethnic group (see Table 1).

Outcome measures

Challenging behaviour

The frequency, management difficulty and severity of

each behaviour listed in the Checklist for Challenging

Behaviour (CCB) were measured to identify the primary challenging behaviour for each respective individual in both groups. Frequency is scored from 1

(never) to 6 (hourly or more often); management difficulty from 1 (no problem) to 5 (extreme problem); and

severity from 1 (no injury) to 5 (very serious injury).

Reliability of the instrument is reported to be adequate

(Joyce et al. 2001). Scores on frequency, management

difficulty and severity were summed across individual

behaviours. Behaviours were then ranked from the

highest score to the lowest score. The highest ranked

behaviour was identified for each individual and only

this behaviour was used for subsequent comparisons

before and after the 6-month period of training (see

Table 2). For a sub-sample of 26 individuals with challenging behaviour, two staff members completed the

CCB for the primary challenging behaviour independently for the same individual within a 1-week period.

The Spearman rank-order coefficient was used to

determine inter-rater reliability. Scores were summed

for each of the scales and the Spearman statistic was

used to correlate the total scores for frequency, management difficulty and severity. For frequency, the

correlation co-efficient was 0.86 (two-tailed, P < 0.001,

n 26). For management difficulty the correlation

co-efficient was 0.92 (two-tailed, P < 0.01, n 26)

and for severity the correlation co-efficient was 0.80

1

One service was based in a rural setting (n 19) and the other

was based in the suburb of a major metropolitan area (n 11).

Table 1 Demographic and clinical information at time 1

Variable

Target

(n 30)

Mean age (years)

32

Age range (years)

355

Gender

Male

17

Female

13

Level of disability

Mild

6

Moderate

8

Severe

10

Profound

6

Duration of challenging behaviour as per current case

Mean duration (months)

93

Range (months)

6342

Duration of psychiatric medication as

(n 20)

per medication chart at time 1

Mean duration (months)

109

Range (months)

6345

Units of psychiatric medication time 12

5.0

Range

19

Units of psychiatric medication time 2

4.8

Range

17

DSM diagnosis at time 1

No diagnosis

10

Mood disorder

13

Psychosis

3

Autism

3

ADHD

1

Control

(n 30)

39

370

19

11

6

13

11

0

file1

86

12345

(n 16)

149

24312

4.2

113

4.0

110

21

5

1

3

0

Case notes were examined for information regarding approximate onset of challenging behaviour.

2

Unit equivalencies based upon British National Formulary

(2002).

(two-tailed, P < 0.01, n 26). Table 2 presents the primary challenging behaviour as identified in both

groups as per the CBC for the control group and

referral problem for the target group. For the target

group, observation-based measurement was also

undertaken for the highest ranked behaviour on the

CCB as part of the training process.

Psychotropic medication

Determining the amount of medication received by

each client was done using the British National Formulary (BNF) [British Medical Association (BMA) 2002].

The BNF identifies for each medication the amount

that constitutes one therapeutic unit. For example,

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

10 Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities

Target group challenging

behaviour

Self-injurious behaviour

Exposing body inappropriately

Physical aggression

Verbal and physical aggression

Public masturbation

Lying on the ground

Breaking rules

Loud talking

3

2

14

7

1

1

1

1

Control group challenging

behaviour

Self-injurious behaviour

Exposing body inappropriately

Physical aggression

Verbal and physical aggression

Public masturbation

Stereotyped behaviour

Licking

Stealing

Excessive drinking

4

1

14

5

1

2

1

1

1

100 mg of chlorpromazine (largactil) is one therapeutic

unit and is the equivalent of 1 mg of resperidone (resperdal). The amount of medication per client was calculated by determining the number of units within

each medication across anti-psychotics (typical

and atypical), anti-depressants, mood stabilizers and

anxiolytics using the unit equivalencies provided and

adding them together.

Block one

(3 days)

i.

Assignment

(4 weeks)

Table 2 Challenging behaviours: target

and control groups at time 1

Procedure

Training content

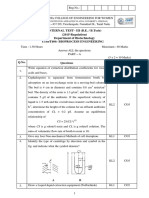

The course comprises nine full days over a 6-month period (see Figure 1). The content of the training course

was adapted from the assessment and intervention protocol developed by the Institute of Applied Behaviour

Block two

(2 days)

Assignment

(4 weeks)

Block three

(1 day)

Functional

ix. Intervention

development

Introduction to

behavioural support

ii.

Environmental

vii. Functionally

accommodation

iii. Skills teaching

Background

equivalent

assessment

assessment

skills teaching

Baseline

viii. Functional

iv. Direct intervention

v.

recording

assessment

Reactive strategies

vi. Behavioural

assessment

Assignment

(4 weeks)

Block four

(1 day)

Assignment

(3 months)

Intervention design

x. Periodic Service

Periodic Service Review

Baseline recording

Review

Quarterly Progress Report

Incident analysis

Block five

(2 days)

Implementation of plan

Case review

Figure 1 Schematic representation of structure and timeframe of person-focused training.

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 11

Analysis (LaVigna & Donnellnan 1989). A cornerstone

of the training format is the use of PFT. Participants

completed three written training assignments (i.e. behaviour assessment report, behaviour support plan and

quarterly progress review) with respect to one individual with whom they directly worked who displayed

challenging behaviours and who had been referred for

psychological input. All behaviour support plans specified interventions across four categories: ecological

changes, skills teaching, direct interventions and reactive

strategies. The training format is identical to that

reported by McClean et al. (2005).

Target group: staff training

A training course was conducted within a large residential setting, and two were conducted within a community-based service. Fifteen staff were qualified nurses,

seven were residential care-staff, four were day service

providers, two were intensive support workers and two

were clinical psychologists not associated with the delivery of the training course. The average duration of frontline staff working with the client was 12 months. No

psychological interventions other than those developed

through the training process were implemented across

the 6-month duration of training. Assessments and subsequent behaviour support plans addressed the highest

ranked behaviour on the CCB.

Control group

Either a nurse or a member of care staff who had been

working with the service user for longer than 6 months

completed the CCB. No formal comprehensive behavioural assessments were conducted for this group during the specified training period nor were behaviour

support plans derived from such assessments implemented.

Administration

The CCB was administered on two occasions for both

groups: prior to the commencement of the first workshop (conducting a behaviour assessment), and

6 months later at the end of the fourth workshop (quarterly progress review on the implementation of the

behaviour support plan). For the target group, individualized appropriate observation-based measures of behaviour took place as part of the functional assessment.

Depending on the nature of the target behaviour, these

included event recording, interval recording or fre-

quency of response. In the majority of cases, these were

typically actual frequency data for the target behaviour.

No observational recording took place for the control

group. No data are available with respect to the reliability of observational recordings for the target group. Unit

equivalencies of psychotropic medication were determined for both groups before and after the training period based on the service users file.

Data analysis

Tests for normality were performed on all variables

used in subsequent analysis. Only severity of challenging behaviour was found to be non-normally distributed. A general ancova model using raw scores was

used (with transformed scores for severity) co-varying

scores at time 1 on the outcome variables. This approach

to data analysis was selected as the design did not

involve random allocation to groups at the outset of the

study. As such, there are likely to be minor differences

between the groups at baseline. ancova models take

account of such variance between groups at baseline

and allow a closer examination of the effects of the independent variable whilst accounting for initial differences

if present. Effect sizes were indexed using the partial

eta-squared co-efficient.

Results

No significant differences were observed between the

groups at the start of training (time 1) on frequency,

management difficulty and severity of challenging behaviour. In addition, no significant differences were

observed between the groups on age, gender, duration

of challenging behaviour and duration of psychiatric

medication. Controlling for frequency of challenging

behaviour at time 1, duration of challenging behaviour,

units of medication, gender, level of disability and diagnosis, a significant effect was observed between the two

groups on frequency of challenging behaviour at time 2

as measured by the CCB [F(1, 38) 13.7, P < 0.001;

g2 0.27] (see Figure 2). At time 2, the average mean

score for frequency for the control group was 3.6 and

the average mean score for the intervention group was

2.5. At time 2, the average mean score for management

difficulty for the control group was 3 and the average

mean score for the intervention group was 1.6. Controlling for management difficulty of challenging behaviour

at time 1, duration of challenging behaviour, units of

medication, gender, level of disability and diagnosis, a

significant effect was observed between the two groups

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

12 Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities

Discussion

The primary finding of the current study is that PFT is

associated with significant reductions for service users

presenting with challenging behaviour and that such

reductions are maintained 6 months after the initial

implementation of behaviour support plans. For twothirds of the target group, the frequency of challenging

behaviour dropped to below 30% of baseline rates after

3 months of implementation of behaviour support plans.

For the remainder, the majority had a rate reduction to

between 70% and 30% of baseline. Taken collectively,

An ancova performed on the untransformed data set indicated a similar result.

These are re-transformed mean scores.

Table 3 Percentage reductions in baseline rates of challenging

behaviour at first quarter

Percentage of

reduction

Number

(n 30)

030% of baseline

3070% of baseline

7080% of baseline

Increase in baseline rate

21

7

1

1

Frequency Time 1

Management Time 2

Frequency Time 2

Severity Time 1

Management Time 1

Severity Time 2

Mean Score

on management difficulty [F(1, 38) 19.4, P < 0.001;

g2 0.34]. As a result of the skew on the severity data,

a transformation using square root was performed on

the data. Controlling for severity of challenging behaviour at time 1, duration of challenging behaviour, units

of medication, gender, level of disability and diagnosis,

a significant effect was observed between the two

groups [F(1, 38) 9.7, P < 0.005; g2 0.20]2 on severity.

At time 1, the average mean score for severity for the

control group was 1.6 and the average mean score for

the intervention group was 1.1.3

For the target group, rates of target behaviour based

on observational measures reduced significantly from

baseline to first quarter (i.e. 3 months after the implementation of the behaviour support plan; t 5.15,

d.f. 29, P < 0.00). The average reduction in frequency

of behaviour across this period was to 24% of baseline

rates for 29 of the 30 service users with challenging

behaviour. The frequency of challenging behaviour was

reduced to below 30% for 21 service users (see Table 3).

Additional data were available at second quarter (i.e.

6 months after implementation of behaviour support

plan) for 19 individuals who had attended two of the

training courses. Rates of challenging behaviour

dropped to 18% of initial baseline at first quarter, and to

11% at second quarter (see Figure 3).

For both target and control groups, there was no significant reduction in the overall number of units of

medication prescribed (control group, t )0.80,

d.f. 28, P < 0.43; target group, t 1.2, d.f. 28,

P < 0.22). There was no significant reduction in the

number of clients being taken off medication for either

group.

0

Target

Control

GROUP

Figure 2 Mean scores on CBC by group.

there was a reduction to 22% of baseline for the target

group at first quarter and a further reduction to 11% for

a sample of 19 service users at the second quarter.

While direct observational recording did not take

place for the control group, frequency of challenging

behaviours as reported on the CCB did not alter significantly throughout the equivalent time period. This finding is in general agreement with previous research

indicating that in the absence of appropriate intervention, challenging behaviours remain chronic (Thompson

& Reid 2002). In contrast, a significant difference was

observed for the target group on all three measures of

the CCB. In interpreting these results, it is important to

bear in mind that there was no significant difference at

the outset of the training period on CCB measures of

frequency, management difficulty and severity between

the target and control group. Furthermore, there was no

significant reduction in the actual number of clients on

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 13

25

Mean rate

20

15

10

0

Baseline

1st quarter

2nd quarter

Figure 3 Rate reduction in challenging behaviour.

psychotropic medication or in the relative number of

units of psychotropic medication prescribed. While there

was a higher number of clients in the target group with

a formal mental health diagnosis, all had been on psychotropic medication for at least 6 months prior to the

training course. Therefore, the effects of such medication

would have most likely had therapeutic effects by the

commencement of the training course. However, medication changes in the 6 months preceding the training

course were not tracked. In the light of both of these

observations, reductions in frequency of challenging

behaviour and maintenance of such reductions can be

attributed to PFT.

These results are further consolidated in the light of

the ancova results. When duration of challenging behaviour, units of psychotropic medication, gender, level of

disability and diagnosis are controlled for at the start of

the training period, there is a significant difference

between the groups at the end of the training period on

the CCB measures of frequency, management difficulty

and severity. Furthermore, the effect sizes for these variables was substantial with figures of 27%, 34% and 20%

respectively.

While the behaviour support plans developed through

PFT were effective in supporting individuals with challenging behaviour both in this study and those in

McClean et al. (2005), it remains unclear what ingredients

of these behaviour support plans are most effective.

Although outside the scope of the present research,

future studies may consider coding interventions into the

four general categories (ecological/antecedent change,

skills teaching, direct interventions/motivation and

reactive interventions) and subsequently tracking the

daily/weekly implementation of interventions and determine their respective relationships to defined outcomes.

These results are largely in line with those of McClean

et al. (2005) on PFT as an effective model of service

delivery. Specifically, they reported that training staff to

conduct functional assessments and to design and

implement behaviour support plans was associated with

significant improvements in 77% of service users presenting with challenging behaviour. Using the same criteria for improvement (i.e. reductions to below 30% of

baseline), improvements were reported for almost 70%

of the target group. These findings also lend support to

the argument by McClean et al. (2005) that in services

where challenging behaviours are highly prevalent, consultation may be a far more expeditious model of service delivery than specialist intervention.

The findings should however be interpreted within

the light of certain methodological considerations. First,

though a control group was utilized in this study, allocation to groups was not randomized which would have

strengthened the findings. However, in clinical settings

with pressing demands for intervention from management and care-staff it is not always possible to meet

such criteria. Second, there are issues with respect to the

use of the CCB to detect behaviour change and its usage

in this study. There is limited research available on the

effectiveness of the CCB in detecting behaviour change

across time and perhaps an alternative instrument

would have been more appropriate. To date, however,

no extensive review has been conducted on this issue. A

further difficulty with the CCB is that it was used in a

non-blind fashion (i.e. completed by the person in the

intervention condition), which is a methodological

weakness of most studies relying on self-report measures (Sturmey 2002). Ideally, a second staff member

could be identified for each service user in the target

group and they could complete pre- and post-measures

without undergoing training. Although subsequent comparison would be interesting, it is unlikely whether this

would meet the criterion for a blind rating as support

plans are developed in consultation with the entire team

and therefore all care staff would be familiar with the

support plan. A further measurement issue is the

absence of an inter-observer agreement procedure for

the target group with respect to observation based

measures. As a result, caution must be exercised in the

interpretation of results in this area.

An additional limitation concerns generalization.

Many clients presenting with challenging behaviour

do so with more than one topography or type. Many

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

14 Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities

service users in the target group presented with several

challenging behaviours and it possible that reductions in

the frequency, management difficulty or severity of challenging behaviours other than that directly targeted may

have may have taken place. However, this was not

explored in the current study but should be a focus of

future research investigating PFT.

The accuracy of some of the demographic information

must also be questioned. There was a substantial discrepancy across files in respect of information available

for service users in both groups. In particular, existing

psychiatric diagnosis for clients was drawn from available files and not based upon using a recognized and

accurate diagnostic assessment template. All diagnoses

on file were clinician-based. Future work should employ

a standardized assessment template across all clients

administered by highly experienced practitioners. Furthermore, in this study, the use of psychotropic medication was tracked using the method of unit equivalency

from the BNF. Although the number of units across

both groups did not change significantly across the duration of PFT, it is possible that changes within the total

number of units occurred in some cases. As such, the

use of combined unit equivalency alone is a somewhat

crude measure to track the use of psychotropic medication. A more accurate method would involve the tracking of unit equivalencies within categories of

psychotropic medications such as antidepressants across

time.

The role of supervisory arrangements and specifically

the frequency of such arrangements remains unclear in

the current study. Previous research clearly indicates

that a critical factor in the maintenance of staff behaviour post-training is supervisor feedback (Parsons &

Reid 1995). Ager & OMay (2001) argue that the organizational factors such as the facilitation of effective

supervisory arrangements are critical in the maintenance

of interventions although this appears to require the

deployment of consultants whose continued input

appeared to be necessary for the behaviour changes of

staff members to be retained at high levels (Harchik

et al. 1992). Equally important is the issue of quality control in respect of services and is considered by some as

a necessary surveillance system of the quality of contexts and interactions in the lives of those with disabilities.

They further propose that the clear challenge is to

establish interventions and structures which foster reappraisal of staff assumptions and expectancies regarding

behaviourally based interventions. It would appear that

PFT may go some way to achieving this end.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all staff who participated in the study and also Dr David Hevey of the

School of Psychology for expert statistical advice.

Correspondence

Any correspondence should be directed to Ian Grey,

School of Psychology, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland

(e-mail: igrey@tcd.ie).

References

Ager A. & O May F. (2001) Issues in the definition and implementation of best practice for staff delivery of interventions for challenging behaviour. Journal of Intellectual &

Developmental Disability 26, 243256.

Anderson D. J., Lakin K., Hill B. K. & Chen T. (1992) Social

integration of older persons with mental retardation in residential facilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation 96,

488501.

British Medical Association (BMA) (2002) British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical

Society of Great Britain, London.

British Psychological Society (2004) Psychological interventions for

severely challenging behaviours shown by people with learning

disabilities clinical practice guidelines. St. Andrews House,

Leicester.

Bruininks R., Hill B. K. & Morreau L. E. (1988) Prevalence and

implications of maladaptive behaviours and dual diagnosis

in residential settings. In Mental Retardation and Mental Health:

Classification, Diagnosis, Treatment Services (eds J. A. Stark, F. J.

Menolascino, M. H. Albarelli & V. C. Gray), pp. 147173.

Springer-Verlag, New York.

Carr E. G., Horner R. H., Turnbull A. P., Marquis J. G., McLauglin D. M., McAtee M. L., Smith C. E., Ryan K., Ruef M.

B., Doolabh A. & Braddock D. (1999) Positive Behavior Support

for People with Developmental Disabilities: A Research Synthesis.

American Association on Mental Retardation, Washington,

DC.

Carr E. G., Dunlap G., Horner R. H., Koegel R. L., Turnbull A.

P., Sailor W., Anderson J. L., Albin R. W., Koegel L. & Fox E.

(2002) Positive behavior support: Evolution of an applied

science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 4, 416.

Emerson E. (2001) Challenging Behaviour: Analysis and Intervention in People with Severe Intellectual Disabilities 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Emerson E. & Bromley J. (1995) The form and function of challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

39, 388398.

Emerson E. & Emerson C. (1987) Barriers to the effective implementation habilitative behavioural programs in an institutional setting. Mental Retardation 25, 101106.

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 15

Emerson E. & Forrest J. (1996) Community support teams for

people with learning disabilities and challenging behaviour.

Journal of Mental Health 5, 395405.

Feldman M., Atkinson L., Foti-Gervais L. & Condillac R. (2004)

Formal versus informal interventions for challenging behaviour in persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 48, 6068.

Grey I. M. & Hastings R. (2005) Evidence based practice in the

treatment of behaviour disorders in intellectual disability.

Current Opinion in Psychiatry 18, 469475.

Harchik A. E., Sherman J. A., Sheldon J. B. & Strouse M. C.

(1992) Ongoing consultation as a method of improving performance of staff members in a group home. Journal of

Applied Behaviour Analysis 25, 599610.

Harper D. C. & Wadsworth J. S. (1993) Behavioural problems

and medication utilization. Mental Retardation 31, 97103.

Jahr E. (1998) Current issues in staff training. Research in Developmental Disabilities 19, 7387.

Joyce T., Ditchfield H. & Harris P. (2001) Challenging behaviour

in community services. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

45, 130138.

Knoster T., Anderson J., Carr E., Dunlap G. & Horner R. (2003)

Emerging challenges and oppertunities. Journal of Positive

Behavior Interventions 5, 183186.

Larson S. (1991) Quality of life for people with challenging

behaviour living in community settings. Impact 4, 45.

LaVigna G. W. & Donnellnan A. M. (1989) Behavior Assessment

and Intervention Guide. Institute for Applied Behavior Analysis

Press, Los Angeles, CA.

LaVigna G. W., Willis T. J., Shaull J. F., Abedi M. & Sweitzer

M. (1994) The Periodic Service Review: A Total Quality Assurance

System for Human Services & Education. Paul Brookes Publishing, Baltimore.

McClean B. & Halliday A. (1999) Positive futures planning: a

different kind of service. Frontline 40, 2327.

McClean B. & Walsh P. (1995a) An organisational response to

challenging behaviour. Positive Practices 1, 38.

McClean B. & Walsh P. (1995b) Positive programming an

organisational response to challenging behaviour. Positive

Practices 1, 38.

McClean B., Dench C., Grey I. M., Shanrahan S., Fitzsimmons

E. M., Hendler J. & Corrigan M. (2005) Outcomes of person

focused training: a model for delivering behavioural supports

to individuals with challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 49, 340353.

McGillivray J. & McCabe M. P. (2004) Pharmacological management of challenging behavior of individuals with intellectual

disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities 25, 523537.

Parsons M. B. & Reid D. H. (1995) Training residential supervisors to provide feedback for maintaining staff teaching skills

with people who have severe disabilities. Journal of Applied

Behavior Analysis 28, 317322.

Robertson J., Emerson E., Pinkney L., Caesar E., Felce D., Meek

A., Carr D., Lowe K., Knapp M. & Hallam A. (2005) Treatment and management of challenging behaviours in congregate and noncongregate community-based supported

accommodation. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 49,

6372.

Singh A. N., Matson J. L. & Cooper C. L. (2005) The use of risperidone among individuals with mental retardation: clinically supported or not. Research in Developmental Disabilities

26, 203218.

Snell M., Voorhees M. & Chen L. (2005) Team involvement

in assessment-based interventions with problem behaviour.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 7, 140152.

Sprague J. R., Flannery B., ONeill R. & Baker D. J. (1996)

Effective Behavioural Consultation: Supporting the Implementation of Positive Behaviour Support Plans for Persons

with Severe Challenging Behaviours. Specialised Training

Program, Eugene, OR, USA.

Stancliffe R. J., Hayden M. F. & Lakin K. C. (1999) Effectiveness

of challenging behaviour IHP objectives in residential settings: a longitudinal study. Mental Retardation 37, 483493.

Sturmey P. (2002) Mental retardation and concurrent psychiatric disorder: assessment and treatment. Current Opinion in

Psychiatry 15, 489495.

Thompson C. L. & Reid A. (2002) Behavioural symptoms

among people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities: a 26-year follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry

181, 6771.

Watson A., Rutterford N. A., Shortland D., Williamson N. &

Alderman N. (2001) Reduction of chronic aggressive

behaviour ten years after brain injury. Brain Injury 15, 1003

1015.

2007 BILD Publications, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 615

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- 09 WA500-3 Shop ManualDocument1.335 pagini09 WA500-3 Shop ManualCristhian Gutierrez Tamayo93% (14)

- Marine Lifting and Lashing HandbookDocument96 paginiMarine Lifting and Lashing HandbookAmrit Raja100% (1)

- Loading N Unloading of Tanker PDFDocument36 paginiLoading N Unloading of Tanker PDFKirtishbose ChowdhuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aluminum 3003-H112: Metal Nonferrous Metal Aluminum Alloy 3000 Series Aluminum AlloyDocument2 paginiAluminum 3003-H112: Metal Nonferrous Metal Aluminum Alloy 3000 Series Aluminum AlloyJoachim MausolfÎncă nu există evaluări

- As 60068.5.2-2003 Environmental Testing - Guide To Drafting of Test Methods - Terms and DefinitionsDocument8 paginiAs 60068.5.2-2003 Environmental Testing - Guide To Drafting of Test Methods - Terms and DefinitionsSAI Global - APACÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic DfwmacDocument6 paginiBasic DfwmacDinesh Kumar PÎncă nu există evaluări

- Richards Laura - The Golden WindowsDocument147 paginiRichards Laura - The Golden Windowsmars3942Încă nu există evaluări

- Weekly Learning PlanDocument2 paginiWeekly Learning PlanJunrick DalaguitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basics: Define The Task of Having Braking System in A VehicleDocument27 paginiBasics: Define The Task of Having Braking System in A VehiclearupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fernando Salgado-Hernandez, A206 263 000 (BIA June 7, 2016)Document7 paginiFernando Salgado-Hernandez, A206 263 000 (BIA June 7, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Urun Katalogu 4Document112 paginiUrun Katalogu 4Jose Luis AcevedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- MOTOR INSURANCE - Two Wheeler Liability Only SCHEDULEDocument1 paginăMOTOR INSURANCE - Two Wheeler Liability Only SCHEDULESuhail V VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form Three Physics Handbook-1Document94 paginiForm Three Physics Handbook-1Kisaka G100% (1)

- A Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Document73 paginiA Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Os MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cdi 2 Traffic Management and Accident InvestigationDocument22 paginiCdi 2 Traffic Management and Accident InvestigationCasanaan Romer BryleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Micron Interview Questions Summary # Question 1 Parsing The HTML WebpagesDocument2 paginiMicron Interview Questions Summary # Question 1 Parsing The HTML WebpagesKartik SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strobostomp HD™ Owner'S Instruction Manual V1.1 En: 9V DC Regulated 85maDocument2 paginiStrobostomp HD™ Owner'S Instruction Manual V1.1 En: 9V DC Regulated 85maShane FairchildÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home EconomicsDocument47 paginiExtent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home Economicschukwu solomon75% (4)

- Unit 2Document97 paginiUnit 2MOHAN RuttalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MDOF (Multi Degre of FreedomDocument173 paginiMDOF (Multi Degre of FreedomRicky Ariyanto100% (1)

- Missouri Courts Appellate PracticeDocument27 paginiMissouri Courts Appellate PracticeGeneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 V 6 PlexiDocument8 pagini6 V 6 PlexiFlyinGaitÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18PGHR11 - MDI - Aditya JainDocument4 pagini18PGHR11 - MDI - Aditya JainSamanway BhowmikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oem Functional Specifications For DVAS-2810 (810MB) 2.5-Inch Hard Disk Drive With SCSI Interface Rev. (1.0)Document43 paginiOem Functional Specifications For DVAS-2810 (810MB) 2.5-Inch Hard Disk Drive With SCSI Interface Rev. (1.0)Farhad FarajyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- BYJU's July PayslipDocument2 paginiBYJU's July PayslipGopi ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- WEEK6 BAU COOP DM NextGen CRMDocument29 paginiWEEK6 BAU COOP DM NextGen CRMOnur MutluayÎncă nu există evaluări

- SCDT0315 PDFDocument80 paginiSCDT0315 PDFGCMediaÎncă nu există evaluări

- EnerconDocument7 paginiEnerconAlex MarquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 004-PA-16 Technosheet ICP2 LRDocument2 pagini004-PA-16 Technosheet ICP2 LRHossam Mostafa100% (1)

- A PDFDocument2 paginiA PDFKanimozhi CheranÎncă nu există evaluări