Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Why We Fight

Încărcat de

api-291420899Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Why We Fight

Încărcat de

api-291420899Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Why We Fight

By Thomas W. Bohn

On August 18, 1941, the U.S. House of

Representatives voted 203 yes vs 202 no to

extend the Selective Service Act. By a legislative

eyelash, this countrys reluctance for international

commitment was dramatically demonstrated.

Less than four months later, that reluctance would

be irrevocably shattered. A peacetime Army, suddenly thrust into war, was still not certain who, what

or why it was fighting. A series of morale lectures

delivered by Army officers to soldiers bone tired

from basic training was baffling, bewildering or just

boring. Faced with instilling a deeper sense of urgency and meaning to the War, General George C.

Marshall directed the preparation of a series of films

to replace the lectures.

Intended as a series of orientation films for all

Army troops before they went overseas, the Why

We Fight Series consisted of seven separate films

produced between 1942-45 by the US Army Signal

Corps under the supervision of Academy Award winning director Frank Capra. Capra was recruited specifically by Marshall and early in 1942 was charged

with the task of maintaining morale and instilling loyalty and discipline into the civilian Army being assembled to make war on professional enemies

through a series of films.

In answer to this charge, Capra assembled a team and

set about producing seven films in less than three

years. In addition to Capra, other key Hollywood

personnel associated with the Series included director

Anatole Litvak, editor William Hornbeck, writers

Anthony Veiller and Eric Knight, composer Dimitri

Tiomkin, and narrator Walter Huston.

The overall style of the series was based on the

compilation format, a method of creating meaning

and narrative by blending previously unrelated visuals of documentary footage through editing and adding strong doses of narration and music. Each film in

the series was unique and stand-alone. The first and

last films in the Series, Prelude to War (1942) and

War Comes to America (1945) are primarily history

lessons focused on how and why America was

fighting this war. Indeed, a clear indicator of the

premise of the entire Series is the change in the title

of the last film in the Series from America Goes to

War to War Comes to America. Both films contrast

two world orders - Axis and Allied and Slave and

Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, commander of U.S. Forces in the

European theater of operations, decorates Lt. Col. Frank

Capra with the Legion of Merit award. Courtesy Library of

Congress Prints & Photographs Online Collection.

Free - with major emphasis on the events and reasons leading up to war. The Nazis Strike (1943)

and Divide and Conquer (1943) are battlefield films

with an emphasis on overall Nazi war strategy and

campaign tactics. Taking place in a limited arena of

space and time they focus on specific battles designed to impress upon Americas young troops, the

ruthlessness and battle hardened strength of the

German Army. The remaining three films, The

Battle of Britain (1943), The Battle of Russia (1943) and The Battle of China (1944) were

ally films emphasizing that America was not

fighting the war alone and these countries had

fought longer, suffered direct assault on their people

and lands, and had bought time for the United

States prior to December 7, 1941.

Visually, the films operate on a dual premise - to

communicate information about and to increase understanding of the causes of World War II. There

was an emphasis on proving this by using newsreel, documentary, and battlefield footage. For example, The Battle of Russia contained approximately 7,400 feet of film. Of this total, some 4,500

feet were from Russian feature productions, documentary films, combat footage, and newsreels. As

this was film originally shot for another purpose and,

as such, represents found footage, in order to create meaning and develop a consistent narrative,

Capra and his team used editing as the principal stylistic building block for the Series. Many of the basic

stylistic elements familiar to Capra - shot composition, movement, lighting, set design, acting - were

not available or used. As film historian Richard

Griffith noted, Deprived of star glamour and production value, drawing their material from newsreel archives and combat film photographed at random,

they were forced back upon the basic resources of

the film medium.

The films were short by Hollywood standards, averaging 57 minutes each. Since the Series basic

theme was one of contrasting the slave and free

worlds, Capras parallel editing style worked very effectively and efficiently. The dominant transition between shots was the cut and the average shot length

was 3.5 seconds. The overall pace of the film was

rapid but not pell-mell. There was a distinct and deliberate editing pattern and rhythm in the films designed to communicate information and increase understanding coherently, efficiently, and repeatedly.

Stitching together a coherent narrative, however, also required the liberal and creative use of music and

narration. Walter Huston was the principal narrator of

the Series. His voice is older, raspy, and filled with

authority. The narration is colloquial and conversational befitting the intended audience for the films,

one-third of whom had not finished high school. In

Prelude to War, for example, the Axis powers are

described as all hopped up with the same ideas

and Mussolini beat his chest like Tarzan. In The

Battle of Britain the narrator states, The pace was

too hot. Something had gone haywire. The Nazis

had to call time out.

The music for the films was composed and coordinated by well-known Hollywood composer Dimitri

Tiomkin. Tiomkin created the score for each film after

it had achieved its final form and described himself

weeping over the moviola as he composed.

The music is elementary, repetitive, and designed for

immediate and easy appeal. Like the narration, it is

familiar and often colloquial, and designed to convey

a strong and immediate emotional tone and meaning.

For example, in War Comes to America, Rhapsody

in Blue is used with footage describing the history

and growth of America. My Country Tis of Thee is

often used as a musical coda describing the United

States. This Is the Army, Mr. Jones is used in a sequence describing the first peacetime draft.

The film historian Richard MacCann has described

The Why We Fight series as a combination of a

sermon, a between halves pep talk, and a barroom

bull session. While this is an apt description, it is

somewhat incomplete. Burdened with the task of

making the war understandable and acceptable,

The Why We Fight series is also an American history lesson and posits a clear and compelling moral

philosophy. The Series was designed to both inform

and inspire; to show Army troops what they were

fighting for and why. Employing the compilation format, visuals of unrelated and unconnected reality

were edited into a cohesive and compelling argument, with music and narration providing an emotional undercurrent. Historically, the Series was a meeting of the talent of a commercial film industry, a

strong tradition of documentary film, and the needs

of war. All of this worked to produce what most critics

and historians acknowledge were the finest documentary films of World War II.

The views expressed in these essays are those of the author and do

not necessarily represent the views of the Library of Congress.

Dr. Thomas W. Bohn received his Ph.D. from the University

of Wisconsin-Madison in 1968. He served as Dean of the

Park School of Communications at Ithaca College from

1980 -2003.Dr. Bohn is the author/co-author of four books

including Mass Media: An Introduction to Modern

Communication and Light and Shadows: A History of

Motion Pictures. Dr. Bohn is retired and teaches part-time

in mass communication and film history at Ithaca College.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Why We Fight PDFDocument2 paginiWhy We Fight PDFAntony LawrenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- German Ways of War: The Affective Geographies and Generic Transformations of German War FilmsDe la EverandGerman Ways of War: The Affective Geographies and Generic Transformations of German War FilmsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why We Fought: America's Wars in Film and HistoryDe la EverandWhy We Fought: America's Wars in Film and HistoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (1)

- Bodnar - Saving Private Ryan and Postwar PDFDocument14 paginiBodnar - Saving Private Ryan and Postwar PDFHernando Escobar VeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hollywood As Historian: American Film in a Cultural ContextDe la EverandHollywood As Historian: American Film in a Cultural ContextEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil WarDe la EverandCauses Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil WarEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (15)

- Inventing Vietnam: The War in Film and TelevisionDe la EverandInventing Vietnam: The War in Film and TelevisionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- Hymns for the Fallen: Combat Movie Music and Sound after VietnamDe la EverandHymns for the Fallen: Combat Movie Music and Sound after VietnamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bowen Brothers FinalizedDocument15 paginiBowen Brothers Finalized邓明铭Încă nu există evaluări

- Destructive Sublime: World War II in American Film and MediaDe la EverandDestructive Sublime: World War II in American Film and MediaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Columbia Companion to American History on Film: How the Movies Have Portrayed the American PastDe la EverandThe Columbia Companion to American History on Film: How the Movies Have Portrayed the American PastÎncă nu există evaluări

- World at War Review by Max HastingsDocument5 paginiWorld at War Review by Max HastingsZiggy Mordovicio100% (1)

- Chapter 8 - History On FilmDocument12 paginiChapter 8 - History On FilmKorina MarawisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cinema on the Front Line: British Soldiers and Cinema in the First World WarDe la EverandCinema on the Front Line: British Soldiers and Cinema in the First World WarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chen Inquiry2 EditDocument6 paginiChen Inquiry2 EditperpetuamotusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film NoirDe la EverandStreet with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film NoirEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- Chapman - War and FilmDocument285 paginiChapman - War and Filmaliamri100% (2)

- War without Bodies: Framing Death from the Crimean to the Iraq WarDe la EverandWar without Bodies: Framing Death from the Crimean to the Iraq WarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The naval war film: Genre, history and national cinemaDe la EverandThe naval war film: Genre, history and national cinemaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940–1941: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl HarborDe la EverandThe Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940–1941: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl HarborEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (9)

- American Veterans on War: Personal Stories from WW II to AfghanistanDe la EverandAmerican Veterans on War: Personal Stories from WW II to AfghanistanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Online CasebookDocument5 paginiOnline Casebookapi-483717074Încă nu există evaluări

- Shadows on the Past: Studies in the Historical Fiction FilmDe la EverandShadows on the Past: Studies in the Historical Fiction FilmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cowboys As Cold Warriors: The Western And U S HistoryDe la EverandCowboys As Cold Warriors: The Western And U S HistoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- War in Film: Semiotics and Conflict Related Sign Constructions on the ScreenDe la EverandWar in Film: Semiotics and Conflict Related Sign Constructions on the ScreenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Megan Condis - Casablanca's Cult Film Propaganda StrategyDocument9 paginiMegan Condis - Casablanca's Cult Film Propaganda StrategyJoro SongsongÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Dead Ends to Cold Warriors: Constructing American Boyhood in Postwar Hollywood FilmsDe la EverandFrom Dead Ends to Cold Warriors: Constructing American Boyhood in Postwar Hollywood FilmsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American CultureDe la EverandCold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American CultureÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1914 1918 Online Filmcinema 2015 08 20Document18 pagini1914 1918 Online Filmcinema 2015 08 20Mădălina OpreaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greek Cinema Volume 3 Documentaries and Short Movies 032212 PDFDocument502 paginiGreek Cinema Volume 3 Documentaries and Short Movies 032212 PDFAntonis EfthymiouÎncă nu există evaluări

- James Chapman - War and Film (Reaktion Books - Locations) (2008)Document285 paginiJames Chapman - War and Film (Reaktion Books - Locations) (2008)Bruno MonteiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Informal ReviewDocument3 paginiInformal Reviewapi-242606123Încă nu există evaluări

- Marching Orders: The Untold Story of How the American Breaking of the Japanese Secret Codes Led to the Defeat of Nazi Germany and JapanDe la EverandMarching Orders: The Untold Story of How the American Breaking of the Japanese Secret Codes Led to the Defeat of Nazi Germany and JapanEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- Textual AnalysisDocument8 paginiTextual AnalysisSheaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life and Death on the Eastern Front: Rare Colour Photographs From World War IIDe la EverandLife and Death on the Eastern Front: Rare Colour Photographs From World War IIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Custer Was Never Warned: The Forgotten Story of the True Genesis of America's Most Iconic Military Disaster, Custer's Last StandDe la EverandWhy Custer Was Never Warned: The Forgotten Story of the True Genesis of America's Most Iconic Military Disaster, Custer's Last StandEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (2)

- Historic Photos of World War II: North Africa to GermanyDe la EverandHistoric Photos of World War II: North Africa to GermanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cold War Movie 1948-65Document2 paginiCold War Movie 1948-65api-230745769Încă nu există evaluări

- Hollywood's West: The American Frontier in Film, Television, & HistoryDe la EverandHollywood's West: The American Frontier in Film, Television, & HistoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (1)

- Five Came Back: Second World WarDocument21 paginiFive Came Back: Second World War§Qµã££ £êøñ]-[ã®TÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fields of Vision: Essays in Film Studies, Visual Anthropology, and PhotographyDe la EverandFields of Vision: Essays in Film Studies, Visual Anthropology, and PhotographyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Documentary FilmsDocument17 paginiDocumentary Filmsআলটাফ হুছেইনÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Glory To Destruction: John Huston's Non-Fictional Depictions of WarDocument15 paginiFrom Glory To Destruction: John Huston's Non-Fictional Depictions of WarkvajdanÎncă nu există evaluări

- MDC Cia IiDocument5 paginiMDC Cia Iidikshagun98Încă nu există evaluări

- Inglourious Basterds: A Battle Through Dramatic LicenseDocument6 paginiInglourious Basterds: A Battle Through Dramatic LicenseperpetuamotusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spielberg Vs KubrickDocument11 paginiSpielberg Vs KubrickJose López AndoainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public Enemies, Public Heroes: Screening the Gangster from Little Caesar to Touch of EvilDe la EverandPublic Enemies, Public Heroes: Screening the Gangster from Little Caesar to Touch of EvilEvaluare: 1 din 5 stele1/5 (1)

- War Pictures: Cinema, Violence, and Style in Britain, 1939-1945De la EverandWar Pictures: Cinema, Violence, and Style in Britain, 1939-1945Încă nu există evaluări

- Vietnam War Helicopter Art: U.S. Army Rotor AircraftDe la EverandVietnam War Helicopter Art: U.S. Army Rotor AircraftÎncă nu există evaluări

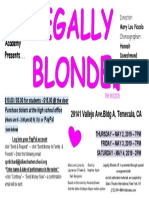

- Legally Blonde Poster 2019Document1 paginăLegally Blonde Poster 2019api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Prosper 1Document8 paginiProsper 1api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- FlyerDocument1 paginăFlyerapi-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Cinderella in Ny Poster 2017Document1 paginăCinderella in Ny Poster 2017api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Jcshsa 2018 2f2019 Lunch CalendarDocument3 paginiJcshsa 2018 2f2019 Lunch Calendarapi-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Cinderella in Ny Poster 2017Document1 paginăCinderella in Ny Poster 2017api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Food DriveDocument1 paginăFood Driveapi-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Show Poster 2017 2Document1 paginăShow Poster 2017 2api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Ms. Mathews's Syllabus JCS Murrieta High School Academy Spring 2016Document5 paginiMs. Mathews's Syllabus JCS Murrieta High School Academy Spring 2016api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Show Poster 2017 2Document1 paginăShow Poster 2017 2api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- SteammakerfestivalflyerDocument1 paginăSteammakerfestivalflyerapi-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Oct Meeting Min W LogoDocument2 paginiOct Meeting Min W Logoapi-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Sept Meeting Min W LogoDocument2 paginiSept Meeting Min W Logoapi-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- 1920s Project Rubric - Sheet1Document1 pagină1920s Project Rubric - Sheet1api-291420899Încă nu există evaluări

- Oswald Bastable and Others - Edith NesbitDocument255 paginiOswald Bastable and Others - Edith NesbitMarielos Livengood de SanabriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parte+1+MacFarlane,+Neil+S +2002Document7 paginiParte+1+MacFarlane,+Neil+S +2002crsalinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Javier Martinez-Jimenez - Monte Barro, An Ostrogothic Fortified Site in The AlpsDocument13 paginiA Javier Martinez-Jimenez - Monte Barro, An Ostrogothic Fortified Site in The AlpsSzekelyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil War Markers Monuments On City of Jacksonville PropertyDocument2 paginiCivil War Markers Monuments On City of Jacksonville PropertyActionNewsJaxÎncă nu există evaluări

- DSKH Ngan Hang Vietcombank Gui TienDocument32 paginiDSKH Ngan Hang Vietcombank Gui TienTi TanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Martial Class Maneuvers - GM BinderDocument4 paginiMartial Class Maneuvers - GM BinderAquila12Încă nu există evaluări

- America's Response To World War IIDocument6 paginiAmerica's Response To World War IIRayhonna WalkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salman H. Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917-1966Document170 paginiSalman H. Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917-1966Jorge Ramos Tolosa100% (8)

- WH Quickstart Chargen v.04Document2 paginiWH Quickstart Chargen v.04jcartaxo2Încă nu există evaluări

- Ganesha Games Catalog June 2022Document154 paginiGanesha Games Catalog June 2022Donpeste0% (2)

- THE ENEMY - MCQsDocument5 paginiTHE ENEMY - MCQsSai TejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Offset-Link Product-Sheet ENDocument2 paginiOffset-Link Product-Sheet ENWallace MarinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 06 Our Tet Holiday Lesson 1 Getting StartedDocument17 paginiUnit 06 Our Tet Holiday Lesson 1 Getting StartedndthanhtphueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Korean WarDocument6 paginiKorean WarDaniel AhnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smileys London Mike Hall MapDocument1 paginăSmileys London Mike Hall MapJessica RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ammunition, Barrels, and Accuracy of AR-10B Rifles - Tnote20Document5 paginiAmmunition, Barrels, and Accuracy of AR-10B Rifles - Tnote20rectangleangleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Principles of IHLDocument3 paginiBasic Principles of IHLKristine RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instruction Manual: HatsanDocument8 paginiInstruction Manual: HatsanAlejandro Patricio Cornejo NaranjoÎncă nu există evaluări

- U.S. Security Assistance To UkraineDocument3 paginiU.S. Security Assistance To UkrainekevinÎncă nu există evaluări

- IL2 Aircraft Identification GuideDocument19 paginiIL2 Aircraft Identification GuideKitzÎncă nu există evaluări

- 42 Portuguese Dragoons 1966-1974 The Return To Horseback (E)Document70 pagini42 Portuguese Dragoons 1966-1974 The Return To Horseback (E)juan100% (2)

- Bulwark Final PDFDocument80 paginiBulwark Final PDFRx VilleÎncă nu există evaluări

- School Calendar 2024 2025Document1 paginăSchool Calendar 2024 2025api-356067070Încă nu există evaluări

- BTR 60MK BrochureDocument16 paginiBTR 60MK BrochureAlbert AbessonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dragon 017 - Tesseracts - Gary Jordan (Aug 1978)Document2 paginiDragon 017 - Tesseracts - Gary Jordan (Aug 1978)Mr xvxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Black Hoof: Catecahassa or Black Hoof (C. 1740-1831) Was The Head CivilDocument2 paginiBlack Hoof: Catecahassa or Black Hoof (C. 1740-1831) Was The Head CivilTeodoro Miguel Carlos IsraelÎncă nu există evaluări

- GF - Robot Legions v2.12Document3 paginiGF - Robot Legions v2.12Tom MuscoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2eoi Medpa 2075 IvdsDocument17 pagini2eoi Medpa 2075 Ivdskanchan ghimireÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carlo Domeniconi - SindbadDocument81 paginiCarlo Domeniconi - Sindbadnutshelll100% (4)

- Sellswords - Core Rules v0.24Document7 paginiSellswords - Core Rules v0.24Radosław SekułaÎncă nu există evaluări