Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Homonymshomophoneshomographs

Încărcat de

api-320884146Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Homonymshomophoneshomographs

Încărcat de

api-320884146Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

2007 INTERNATIONAL READING ASSOCIATION (pp. 98111) doi:10.1598/JAAL.51.2.

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching

English-language learners to comprehend

and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Julie Jacobson, Diane Lapp, James Flood

Learning more day by day

The instructional process described in this

So many words I can now read

article can be used to teach all students, but

Yet sounds and meanings, I must say

Have not always agreed

it especially accommodates the

Jacobson teaches language

(By Jacobson, Lapp, & Flood, 2006)

challenges encountered by

learners at Scripps Ranch

High School in the San Diego

English-language learners.

Do You Here or Hear What I

Hear?

Words can be quite deceiving

I have found

Words can have a double meaning

And sometimes a double sound

Unified School District

(10838 Sunny Meadow St.,

San Diego, CA 92126, USA).

E-mail Jacobsonmail1@

aol.com. Lapp teaches at

San Diego State University,

as did the late Jim Flood. Email lapp@mail.sdsu.edu.

We have there and their and here and hear

Watch what youre choosing

If its not very clear,

It can all be quite confusing!

Can you tell me, if the clerk keeps records

And a song the musician can record

How can I make sense of words

like these that cant be ignored?

Although a lawyer yells

I contest!

Its in a contest of words, he tells

Where he is at his best

I must declare

As I try to glean each word

That some words of a pair

Are the strangest Ive ever heard!

98

Mr. Ryans awareness of the difficulties

mentioned in this poem was heightened as he and his middle school students discussed the short story, The

Mayan Civilization, that he had selected from Latino Read-Aloud Stories

(Suarez-Rivas, 2000). As the students

silently read a section, Mr. Ryan noticed that Juan

(all names are pseudonyms), a student who had

scored at the Early Intermediate level on his

English-language proficiency test looked particularly frustrated.

Like teachers who scaffold instruction from

their formative and continual evaluation of student performance, Mr. Ryan initiated the following conversation to gain more insight about

Juans thinking:

Mr. Ryan: I notice that you have written a few words

in the Difficult Words section of your vocabulary journal.

Juan:

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

Im having trouble with the words feat and

reigned. I understood that we should

sound out new words, but I still cant understand these words. I know f-e-e-t and

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

r-a-i-n-e-d, but these words dont make

sense in this story.

Mr. Ryan: You are right when you say these words

sound like feet and rained. You might be

confused because even though they sound

the same, they are spelled differently and

have different meanings. Words like these

are called homophonessame sounds with

different spellings and meanings. Im so

glad that you are thinking about the word

and what it would mean in a particular

sentence. If it doesnt make sense to you, it

may be that even though it sounds like a

word you know, it has a different meaning.

Thats the case with feat and reigned. In

this story, the word f-e-a-t means an accomplishment or a completed task. R-e-ig-n-e-d means ruled. Lets use your

dictionary to check the meaning of these

words, and then well go back to the text to

see if it makes more sense to you.

After Mr. Ryan demonstrated how to search

for words in the dictionary and showed Juan the

spelling of each word, he drew a picture of a king

on a throne and explained that the illustration

showed that a ruler reigns over a specific group of

people. Mr. Ryan pointed to a poster he had in

the room of a pole-vaulter and explained that the

athlete was accomplishing a difficult feat that

could help him to be a record setter. He further

explained that

there are also words like record and record that share

the same spelling but are pronounced differently.

These are called homographs. Words and phrases can

have many meanings or connotations. This often de-

pends on either their spelling or the context of the

sentence in which they occur.

As Juan wrote the definitions of feat and

reigned with pictures and sentences in his vocabulary journal, Mr. Ryan praised his careful reading

and invited him to take some time to polish his

pictorial representation of the words and to share

his examples later in the day when the class would

be discussing homophones and homographs.

This interaction reminded Mr. Ryan that although many of his beginning and intermediate

English-language students knew one meaning of

a word, they didnt realize the concepts of homonym, homophone, or homograph or further understand into which category a word goes. Most

of Mr. Ryans students read at first-through sixthgrade levels and often experienced difficulty

grasping the vocabulary in their school texts.

Of the 10 English-language learners in Mr.

Ryans class, 3 had scored at the Beginning level, 5

at the Early Intermediate level, and 2 at the

Advanced level. This distribution is similar to that

of many middle school classrooms involving

English-language learners. Because of these needs,

Mr. Ryans instruction included explicit vocabulary

and reading comprehension strategies designed to

expand students understanding of word meaning.

To help his students understand the phenomenon of homonyms, homophones, and homographs, Mr. Ryan presented sentences (see

Figure 1) containing either a pair or group of

homonyms, homophones, or homographs. He

Figure 1

Sentence pairs

Is it fair that the fair-haired child should attend the county fair? (homonyms)

How is it that a carpenter measures the length of a doorway in feet and can then accomplish a feat with the

tools on his belt? (homophones)

And why do we say a boy can hear the wind blow, and another boy can wind his string around a stick for his

kite? (homographs)

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

99

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Ta b l e 1

T r i c k y Wo r d s w o r d w a l l

Same

sounds

Homonyms:

fair

fair

fair

Homophones:

feet

feat

Homographs:

wind

wind

Different

sounds

Different

spelling

Same

meaning

first asked students to read each word after he

modeled the pronunciation within the sentence

context. This was followed by a discussion about

the sound similarities and spelling and semantic

differences between homophones such as feet and

feat; a discussion of how sounds and meaning can

be different although the spelling is the same as in

the example of homographs such as wind (like

pinned) and wind (like kind); and how homonyms

such as fair, fair, and fair have the same spelling

and pronunciation but different meanings. Mr.

Ryan and the students discussed the meanings of

each italicized word in Figure 1. Then he read the

questions aloud to the students and invited them

to read the questions for themselves. Once he was

sure that his students understood the similarities

and differences, he asked that they use these academic labels when referring to homophones, homographs, and homonyms. He also placed these

words in their appropriate categories on the classroom Tricky Words word wall (see Table 1).

How are homonyms,

homophones, and homographs

alike and different?

Homonyms are words that have the same pronunciation and the same spellings but different meanings or

100

Same

spelling

connotations and, in most cases, different etymological

origins.A bank, for example, can mean a place or organization where money is kept, loaned, or invested,

but it can also mean the land alongside a river, creek, or

pond. Homophones are words that share a single

phonological representation connected to two meanings with different spellings.

Homophones, according to Gottlob,

Goldinger, Stone, and Van Orden (1999), are words

that have the same pronunciation but different

meanings and perhaps different spellings, such as

there (adverb: direction)their (possessive

pronoun)

air (noun: atmosphere)heir (noun: a

person)

knew (verb: to know)new (adjective:

recent)

cord (noun: rope)chord (noun: three

tones in harmony)

Homographs are words that are spelled the

same way but have different meanings and may

have different pronunciations (Smith, 2002).

tear (verb: to rip)tear (noun: shed a tear)

does (verb: to do)does (plural noun: doe)

minute (noun: unit of time)minute

(adjective: small)

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Why should second-language

learners develop academic

language proficiency?

Many experts who research the languageproficiency development of second-language students make a distinction between language that

is used for basic social interaction and language

that is needed for meeting the challenges of

academic coursework and communication

(Cummins, 1980). Basic Interpersonal

Communication Skills are language skills needed

for daily conversational purposes, whereas

Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency refers

to the vocabulary students encounter in academic texts and that they hear in course lectures.

Peregoy and Boyle (2000) suggested that students

might demonstrate basic social competence in a

second language within 6 months to 2 years after

arrival in a new country. The skills related to

talking with friends or managing daily affairs

cannot be equated with the ability to comprehend and express oneself where knowledge of academic vocabulary is required (Cummins, 1981;

Thomas & Collier, 1995). Thomas and Collier

(1995) added that students who lack prior

schooling and who may have very weak or nonexistent primary-language skills may require

from 7 to 10 years to master academic language.

Time needed to become proficient in cognitive

academic language is exacerbated by the peculiarities of learning homonyms, homophones, and

homographs.

For decades, researchers (Hawkes, 1972;

Hudelson, Poyner, & Wolfe, 2003; Readence,

Baldwin, & Head, 1986) have suggested that both

native and nonnative English-speaking students

encounter difficulties with reading comprehension as a result of not understanding the meanings of many words, including homonyms,

homophones, and homographs. This difficulty is

compounded if the second-language speakers

oral proficiency in English has not been acquired

before reading instruction begins (August &

Hakuta, 1997; Strickland, Ganske, & Monroe,

2002).

How can homonyms,

homophones, and homographs

be effectively taught?

The earlier example of Mr. Ryan illustrates how

to effectively provide instruction that extends students understanding of a single correct meaning

for a target word. This scaffolded instruction is

often referred to as a cognitive-constructionist

approach to vocabulary or word study because it

builds upon a learners acquisition of the denotative (e.g., a cat is a feline animal) to connotative

constructions or connections (e.g., catlike, lion,

tiger, leopard, stealthy) when learning to comprehend, distinguish, and express ideas in the

English language.

As Mr. Ryan modeled, students were supported during their reading as he invited them to

analyze words that interfered with their comprehension by noting sounds and sound/letter correspondences among familiar and unfamiliar

words; by connecting and categorizing words

with common sounds, spellings, and different

meanings; and by practicing vocabulary within a

larger language context. This word analysis support illustrates (a) how to compare new words

with one another; (b) how to reinforce previously

learned words; and (c) how to use personal morphological insights about words, context, and the

dictionary to figure out the meaning of words

that are interfering with comprehension.

Mr. Ryan implemented this process when he

worked with Juan. He explained to him that

learning is maximized when examples of familiar

words as well as examples of words that represent

contrasts to a target known word are presented

together. He further explained that language and

reading comprehension are enhanced because the

new vocabulary and information are built or scaffolded from the meaning of a known word to the

new word (Salus & Flood, 2003).

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

101

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

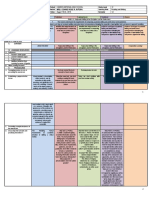

Ta b l e 2

California state standards related to homonyms,

homophones, and homographs

English language

arts substrand

Learner level

Grade level

State standard

Vocabulary and

concept development

Beginning

Grades 35

Spell correctly common homophones (e.g., hair/hare)

Vocabulary and

concept development

Early

Intermediate

Grades 68

Vocabulary and

concept development

Advanced

Grades 912

Recognize that some words (e.g.,

homonyms, homophones, and homographs) have separate meanings

and apply this knowledge to written

text.

Apply knowledge of multiple meanings of wordsincluding

homonyms, homophones, and homographsconsistently in reading

literature and texts in content areas.

Note. This is a configured adaptation of state standards.

Explicit instruction like that of Mr. Ryan is

critical when teaching students who are learning

English as a second or additional language because they frequently encounter unfamiliar words

with dual sounds and multiple meanings.

Although languages such as Spanish include homophones and homographs (e.g., maana/tomorrow and maana/morning), the English

language has the most with over 600 homophone

families (Pryle, 2000). While multiple-meaning

words can also cause confusion for native langauge speakers, this phenomenon is often extremely difficult for English-language learners

(Readence, Baldwin, & Head, 1986).

As noted in the California State English

Language Development Standards (California

Department of Education, 2002), language

should be taught explicitly through explanations,

translations, analogies, paraphrases, and references to context. Table 2 provides a summary of

the California standards that relate to the learning

102

of homonyms, homophones, and homographs,

including the English language arts substrand,

learner level, grade level, and specific standard.

These standards can be addressed through

instruction of words and word families, which incorporate the use of illustrations and realia such

as pictures and photographs that are readily available in picture books, magazines and newspapers,

personal items, and videos. Instruction that models ways to acquire the meaning of an unknown

word provides a foundation of knowledge and a

set of procedures from which students can draw

to independently identify and categorize words

according to sound and meaning when reading,

writing, listening, and conversing (Echevarria,

Vogt, & Short, 2004).

Homonyms, homophones, and homographs can be directly taught as students compare

and contrast words in poetry, fictional literature,

or within the context of content area textbooks

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Ta b l e 3

A seven-step plan for teaching homonyms,

homophones, and homographs

Steps 17

Purpose

Example

1. Read or listen to a story with

homonyms, homophones, or

homographs.

Listening and reading words within

a story or text provide students with

a meaningful academic language

context and models.

A teacher creates a passage based on

her students familiarity with the

struggles between the North and

South before the U.S. Civil War and

reads it aloud.

2. Define and visualize the

words through illustrations.

Visuals help learners to draw

language from their knowledge

and personal experiences.

The teacher defines each word.

Students copy the definition and

create a pictorial image of the word.

3. Identify the grammatical

structure of each word.

Understanding grammatical

structure helps students discern

and evaluate when and how to

use words.

The teacher explains grammatical

characteristics of each word.

Students underline words and

symbols.

4. Categorize words

grammatically.

Analyzing and categorizing words

enhances word recognition and

spelling skills and helps focus on

meanings.

Students use symbols to categorize

words according to grammar.

5. Analyze word meanings to

complete sentences through the

completion of a cloze activity.

Cloze activities provide students with The teacher creates sentences that

an opportunity to demonstrate

require discerning the meaning and

comprehension.

correct usage of words in context.

6. Produce a skit, pantomime, or

create a visual for individual

sentences.

Speaking provides an opportunity

to organize words. Visualizing

facilitates learning and easy

retrieval of new concepts.

In pairs or groups, students present

a skit or a visual depicting a word.

Classmates infer meanings.

7. Determine word meaning.

Metacognitive activities help

students plan, monitor, transfer,

and evaluate their learning.

Students play a game requiring

knowledge of words.

and other supplementary texts that a teacher may

incorporate into the curriculum (Foster, 2003;

Rog & Kropp, 2004). We wish to note the importance of ensuring students comprehension of at

least one word of a pair or series before attempting to teach unknown word meanings. If students

do not have this knowledge prior to instruction,

they may become overwhelmed with the learning

of new vocabulary.

A seven-step plan for teaching

homonyms, homophones, and

homographs

The seven-step model presented in Table 3 provides (a) an instructional sequence for teaching

homonyms, homophones, and homographs; (b)

the rationale for each step; and (c) examples of

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

103

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

implementation that help teachers effectively

teach targeted vocabulary including homonyms,

homophones, and homographs (Jacobson, Lapp,

& Flood, 2003).

The activities included in this seven-step lesson are designed to help students recognize, understand, and produce homonyms, homophones,

and homographs in reading and writing. These

vocabulary-based lessons should be derived from

meaningful contexts, which provide opportunities

to see and hear words used in students literacy exchanges, (Fisher, Lapp, & Flood, 2003). As learners

interact with written and spoken language they

begin to improve their vocabulary, decoding, and

encoding skills and develop enhanced reading

comprehension and writing proficiencies,

(Jacobson, Lapp, & Mendez, 2003; Jacobson,

Moore, & Lapp, 2007).

The foundations of the seven-step plan address students needs to comprehend concepts, engage in meaningful tasks, and use analytical skills to

build and demonstrate language and content

knowledge. Through activities that require students

to visualize concepts they augment their understanding with pictorial images. As words are organized into categories and labels added, a visual

representation is created that becomes a network of

associated words from which target words can be

quickly retrieved from memory. The activities suggested in this seven-step plan involve analyzing the

meanings of words that help students to understand semantic and linguistic connections among

familiar and less familiar words and the meanings

of unknown words (Schwartz & Raphael, 1985).

Although the following example illustrates the

teaching of homophones and homographs, similar

strategies could also be used to teach homonyms.

Implementing the seven-step

plan

Step 1: Reading or listening to the text

Select or create a story or text passage that contains 5 to 20 homophones or homographs. The

104

passage selected for use with advanced students

should be longer than for beginning-level students and should contain both homophones and

homographs. The following paragraph example,

which describes some of the reasons for the U.S.

Civil War, contains both homophones and homographs. After the words have been selected, underline the words that have shared spelling

patterns and sounds. Then invite students to read

or listen to a shared reading of the selected text.

An appropriate text for intermediate- to

advanced-level second-language learners might

look like the following example:

Causes of the U.S. Civil War

The divisions between the North and South began to

tear at the southern states collective commitment to

being legally connected to the northern states. By the

early 19th century, the northern and southern states,

too, had begun to break apart as a result of economic

factors and personal principles. In the North, industry, trade, and commerce had begun to wind through

the states. In the South, however, where modern developments were sparse and smaller in size, expansive

plantations filled the landscape. These manors depended greatly upon slave labor to grow cotton for

export. Through laws that were passed in northern

states, slavery had been banned in the region since

1820. When Abraham Lincoln became president in

1961, his party decided to lead a protest against every

minute detail related to the practice of slavery.

Step 2: Visualizing the meaning

Discuss the meaning of the passage with students

and then model for them how to define and use

each word in a sentence. To do so, ask students to

write selected vocabulary words and definitions

in a vocabulary journal. Provide several examples

of each word as related to its specific meaning in

the text and to familiar homophones (words

with similar sounds) and homographs (words

spelled the same) not present in the text (see

Figure 2). Explain to students that visualizing is a

strategy that can enhance both listening and

reading comprehension. Ask students to illustrate the image the word creates in their mind.

Invite students to practice the pronunciation of

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Figure 2

Homophone and homograph examples

1. Tear (verb)tear (noun)

2. Too (adverb)two (adjective)

3. Break (verb)brake (noun)

4. Principles (noun)principals (noun)

5. Wind (verb)wind (noun)

6. Through (preposition)threw (verb)

7. Where (adverb)wear (verb)

8. Size (noun)sighs (noun [plural] and verb)

9. Manors (noun [plural])manners (noun [plural])

10. Export (noun)export (verb)

11. Lead (verb)lead (noun)led (verb)

12. Minute (adjective)minute (noun)

Figure 3

Visualizing homographs

The wind

The wind

each word as they engage in this activity. An example of this is shown in Figure 3.

Step 3: Identifying grammatical

structures

Reread the text or story aloud. Emphasize each

homophone and homograph and ask students to

underline each word that is a homophone or homograph. After students have listened to the text

again and underlined the target words, explain the

concepts of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and any other

grammatical concepts that are represented by a

homophone in the students text. Invite the students to engage in partner-talk discussions about

additional insights they have about the topic and

the words. Ask students to draw a symbol identifying the word as a noun, verb, adjective, pronoun,

preposition, and any other grammatical structure

you designate. Invite them to represent a noun with

a house, an explosive symbol can represent a verb,

and a happy face can represent an adjective (or they

can label the words as N, V, or A). Finally, explain

that some homophones fall into the same category

(refer to Figure 4).

Step 4: Categorizing words

Provide more practice with vocabulary learning

by asking students to sort and categorize words.

Categories can include nouns (knight/night), action verbs (to run/a run on gasoline; to see/the

sea; knead/need), auxiliary verbs (willfuture

tense/a will; be/bee), adjectives (round/a round of

golf), prepositions (in/inn; to/two/too), personal

or possessive pronouns (their/theyre), or conjunctions (or/ore). Create a word chart with the

students (see Figure 5). In addition, as shown in

Figure 6, words can be categorized through concepts represented by imagery.

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

105

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Figure4

Sample grammar response sheet

Name_________________________________________________________ Date _____________________

1. To lead

5. Minute

2. Two

6. To tear

3. The rights

7. To wind

4. To break

8. A manor

Figure 5

Grammatical word chart

Nouns

Verbs

Action

4. Principles

1. Tear

8. Size

3. Break

9. Manor

5. Wind

10. Export

Linking

Auxiliary

2. Two

12. Minute

11. Lead

Step 5: Analyzing word meanings

within context

Prepare and read aloud cloze sentences that have

a space for the appropriate homophone or homograph. Write each missing word on colored con-

106

Adjectives

struction paper and post it on the front chalkboard. Ask students to read the words aloud and

then fill in each sentence with the appropriate

word. Ask students to accept as correct each completed sentence and discuss the meaning before

proceeding to the next one.

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Figure 6

Wo r d s c a t e g o r i z e d b y i m a g e r y

What I can see

What I can hear

What I can taste

What I can feel

Can you smell...?

The wind

Flower

Bang

Yum!

A manor

Something breaking

Whey

Figure 7

Response guide

Students homophone/homograph response guide

1. Wind

(air)

Wind

(twist)

2. Break

Brake

3. Rights

Writes

4. Way

Weigh

5. Their

There

Examples:

The wind blew through southern fields.

Trade and commerce were able to wind through the northern states.

Step 6: Owning the words

Prepare a list of homophones or homographs that

you would like your students to review. Assign

students in pairs to prepare a short skit or pantomime or to pictorially represent one of each pair

of words. After each dyad presents a description of

the word, ask students to decide which word was

described. Review the meanings and pronunciation of each word before inviting the next pair of

students to present their word description. Finally,

students can write sentences contrasting the

meanings of each word (see Figure 7).

Step 7: Extending and evaluating new

meanings

As an additional review activity, which provides

insights about the students understanding of the

selected topic and the targeted language, you can

prepare 10 to 20 cards with words written on each

side that you would like students to review. You

can develop group sets by making seven to eight

copies of the word cards including pairs of homophones, homographs, and one extra word if you

would like to make the activity challenging for advanced learners. Next, develop a set of cloze sen-

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

107

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Figure 8

S t u d e n ts h o m o p h o n e a c t iv i t y a n d g a m e c a rd s

Seen

Scene

Screen

Right

Write

Rate

Principles

Principals

Primary

Their

There

Theyre

Manors

Manners

Mankind

The road to freedom

1. The topic of the U.S. Civil War, including the causes and the effects, continues to be a subject about which

many authors __________________________________.

2. Northern states enforced laws that protected the _________________________________ of every

persons freedom and liberty.

3. Southern plantation owners had _______________________________ the movement toward abolishing

slavery as a threat to their way of life.

4. Many artists have portrayed a ________________________________ depicting the battles between the

North and the South.

Answer key

1. Write

2. Right

3. Seen

4. Scene

tences (see Figure 8) leaving spaces that require

students to fill them in with a correct word. Invite

students to work in groups of two to four, each selecting a card from the pile of word cards you have

prepared. As each student reads the words, he or

she selects the word that best fits the context of

the sentence and then writes it in the sentence.

Other students fill in the word according to the

students suggestion. If another student disagrees

with the students answer, he or she can fill in a

different sentence. After students have gone

through all of the cards, discussing and evaluating

the correctness of the suggested meanings, you

can provide them with a copy of the answer key.

How can students language

knowledge be formatively and

summatively assessed?

During your teaching of this seven-step plan, you

will be using formative assessment information

108

gained from your insights about student performance to make your next instructional decisions. After teaching the plan, you may want to

assess your students knowledge of the target

words with a simple summative assessment like

the one shown in Figure 9.

One or two more ideas (Or is it

won, or to, or too?)

An additional engaging and instructional activity

that supports the seven-step plan can be found in

Lederers Get Thee to a Punnery (1988). His activity asks students to insert a word in the center of

two words or phrases that are defined by the inserted word (see Figure 10). The teacher develops

a list of homophones or homograph pairs and inserts between them the correct number of underlined, blank spaces for the target word. Students

survey the definitions and the number of blanks,

which indicate the number of letters in the miss-

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Figure 9

A simple summative assessment

Part 1: Homophone assessmentIdentify

The teacher reads aloud the following sentences and choices. Students circle the correct word.

Thinking about our development as a nation

A

1. An important ________________ in our country is the freedom

to speak freely.

write

or

right

2. The North had ensured personal liberty ___________ laws the

individual states had passed.

threw

or

through

3. African Americans often helped one another to find

the ________________ to freedom.

weigh

or

way

Part 2: Homograph assessmentTransfer and develop

Add a meaning

These words share the same sound. Provide a definition or a sentence describing a second use of the word.

For example, A - tail (dogs back appendage)

B - tale Student response: (a story)

A

1. break (to smash, crash)

2. through (to pass in the middle)

3. their (possessive pronoun)

B

(Sample student response)

brake (a pedal or hand gear used to slow a car

or bicycle)

threw (the past tense of to throw, means to toss)

theyre (used to mean they are)

Make a rhyme

These words are pronounced differently. Write a word that rhymes with each word. Then write a sentence

with each word.

A

B

1. tear (sounds like bear)

tear (sounds like fear)

The south wanted to tear away from the union.

The tear came from a soldiers wife.

2. wind (sounds like pinned)

The wind blew during the stormy nights of battle.

ing word. In addition, the teacher provides a

word bank from which students can select the

word that best fits the double meaning of the homophones or homograph pairs. Students then fill

in the blank spaces with a word that reflects the

definitions on both sides.

Students can also keep a special vocabulary

journal of the homophones and homographs

wind (sounds like find)

The plantations in the South

wind around the countryside.

they study. The more opportunities they have to

encounter, interact with, and practice new words,

the more secure they will be in successfully managing the intricacies of the semantics of the

English language. Eventually, students will begin

to internalize these words and use them to communicate their daily ideas and the academic concepts they wish to express.

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

109

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Figure 10

Make a match

1. Metal

lead

To direct

2. Air current

wind

To twist, wrap around

Jacobson, J., Moore, K., & Lapp, D. (2007). Accommodating

differences among English language learners: 75 literacy lessons (2nd ed.). Colorado Springs, CO: PEAK Parent

Center.

Lessons in this book extend those in the first edition through

additional instructional and grouping ideas and materials to

expand oral-language development through peer conversation

and technology engagement.

Student resources

Selecting resources

The following books, designed to address the specific area of homonyms, homophones, and homographs have been written for native speakers

of the language. When using these texts, teachers

should accommodate the needs of secondlanguage learners through activities that reflect

the methods of differentiation presented in this

article, which include accessing prior knowledge,

visualizing, attending to familiarity of concepts,

categorizing words, presenting opportunities to

compare and contrast meanings and sounds,

modeling, using guided instruction, and using assessment that directly reflects words and concepts

that have been studied. We have found that students appreciate and enjoy the approaches described in this seven-step plan because it provides

for an organized process of learning as well as an

outlet for creative expression.

Teacher resources

Gordon, J.A. (1999). Vocabulary building: With antonyms,

synonyms, homophones and homographs. Greenville, CA:

Super Duper Publications.

Explanations and examples of words with semantic similarities and differences are included in this workbook-style text,

which also suggests ready-to-use resources for the classroom.

Jacobson, J., Lapp, D., & Mendez, M. (2003).

Accommodating differences among English language learners: 75 literacy lessons. Colorado Springs, CO: PEAK

Parent Center.

Lesson examples in this book provide teachers with the instructional and grouping ideas and materials needed to differentiate learning for beginning, intermediate, and

advanced English-language learners.

110

Bourke, L.A. (1991). Eye spy: A mysterious alphabet. New

York: Scholastic.

A series of pictures depicting two different homophones or

homographs are presented in this engaging book. For example, the reader opens to the letter A and sees a picture of an insect (the ant) and on the following page a lady (an aunt). The

reader predicts the connection. The book also includes a clue

in the picture to unlock the meaning of the next set of words.

Steere, F.H. (1977). Sound-alike words: Fun activities with

homonyms, homographs, and homophones. Upper Saddle

River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Activities that encourage students to compare and contrast

words with identical sounds as well as those with varying

spelling patterns are well presented in this text.

REFERENCES

August, D., & Hakuta, K. (Eds.). (1997). Improving schooling

for language-minority children: A research agenda.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine.

Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

California Department of Education. (2002). California state

English language development standards. Sacramento, CA:

CDE Press.

Cummins, J. (1980). The construct of language proficiency in

bilingual education. In J.E. Alatis (Ed.), Georgetown

University roundtable on languages and linguistics (pp.

7693). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In C. Leyba (Ed.), Schooling and language

minority students: A theoretical framework (pp. 349). Los

Angeles, CA: Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment

Center, California State University.

Echevarria, J.A., Vogt, M.E., & Short, D.J. (2004). Making

content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP

model (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Fisher, D., Flood, J., & Lapp, D. (2003). Material matters:

Using childrens literature to charm readers (or why

Harry Potter and the princess diaries matter). In L.M.

Morrow, L.B. Gambrell, & M. Pressley (Eds.), Best practices in literacy instruction (pp. 167186). New York:

Guilford.

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

A seven-step instructional plan for teaching English-language learners to comprehend and use homonyms, homophones, and homographs

Foster, G. (2003). Language arts idea bank: Instructional

strategies for supporting student learning. Markham, ON:

Pembroke.

Gottlob, L.R., Goldinger, S.D., Stone, G.O., & Van Orden,

G.C. (1999). Reading homographs: Orographic, phonologic, and semantic dynamics. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 25,

561574.

Hawkes, T. (1972). Metaphor. London: Methuen.

Hudelson, S., Poyner, L., & Wolfe, P. (2003). Teaching bilingual and ESL children and adolescents. In J. Flood, D.

Lapp, J.R. Squire, & J.M. Jensen (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (2nd ed., pp.

421443). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Jacobson, J., Lapp, D., & Flood, J. (2003, December). The use

of familiar versus unfamiliar texts on strategic reading comprehension on nonnative Spanish readers. Paper presented

at the National Reading Conference, 53rd Annual

Meeting, Scottsdale, AZ.

Jacobson, J., Lapp, D., & Mendez, M. (2003).

Accommodating differences among English language learners: 75 literacy lessons. Colorado Springs, CO: PEAK

Parent Center.

Jacobson, J., Moore, K., & Lapp, D. (2007). Accommodating

differences among English language learners: 75 literacy lessons (2nd ed.). Colorado Springs, CO: PEAK Parent

Center.

Lederer, R. (1988). Get thee to a punnery. Charleston, SC:

Wyrick and Company.

Peregoy, S., & Boyle, O. (2000). Reading, writing, & learning

in ESL: A resource book for K12 teachers. New York:

Addison, Wesley, Longman.

Pryle, M.B. (2000). Peek, peak, pique: Using homophones to

teach vocabulary (and spelling!). Voices From the Middle,

7(4), 3844.

Readence, J.E., Baldwin, R.S., & Head, M.H. (1986). Direct

instruction in processing metaphors. Journal of Reading

Behavior, 18, 325339.

Rog, L., & Kropp, P. (2004). The write genre: Classroom activities and mini-lessons that promote writing with clarity,

style, and flashes of brilliance. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Salus, P., & Flood, J. (2003). Language: A users guide: What

we say and why. Colorado Springs, CO: PEAK Parent

Center.

Schwartz, R.M., & Raphael, T.E. (1985). Concept of definition: A key to improving students vocabulary. The

Reading Teacher, 39, 198205.

Smith, C. (2002). Building a strong vocabulary: A twelve-week

plan for students. Bloomington, IN: ERIC/EDINFO Press.

(ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED468896)

Strickland, D., Ganske, K., & Monroe, J. (2002). Supporting

struggling readers and writers. Newark, DE: International

Reading Association.

Suarez-Rivas, M. (Ed.). (2000). Latino read-aloud stories.

New York: Blackdog and Leventhal.

Thomas, W.P., & Collier, V.P. (1995). Language minority

student achievement and program effectiveness.

California Association for Bilingual Education Newsletter,

17(5), 19, 24.

The International Reading Association joins

the literacy community in mourning the passing of Dr. James E. Flood on July 15, 2007. Jim

was an active and valued participant in IRA

publications and Association leadership. We

are honored to feature one of Jims final works

in this issue.

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT & ADULT LITERACY

51:2

OCTOBER 2007

111

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Simile and Metaphor Lesson Plan Grades 4-6Document2 paginiSimile and Metaphor Lesson Plan Grades 4-6api-368414593Încă nu există evaluări

- Lae 3333 2 Week Lesson PlanDocument37 paginiLae 3333 2 Week Lesson Planapi-242598382Încă nu există evaluări

- FL Active and Passive VoiceDocument13 paginiFL Active and Passive VoiceBlessa Marel CaasiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mystery Lesson PlanDocument6 paginiMystery Lesson Planapi-317478721Încă nu există evaluări

- New England Colonies Lesson PlanDocument4 paginiNew England Colonies Lesson PlanRajkovi1Încă nu există evaluări

- Dreamkeepers Reading GuideDocument12 paginiDreamkeepers Reading Guideapi-32464113267% (3)

- Depth of Knowledge (DOK) : Promoting Rigor and Relevance in LearningDocument17 paginiDepth of Knowledge (DOK) : Promoting Rigor and Relevance in Learningapi-226603951Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan 1Document3 paginiLesson Plan 1api-282593322Încă nu există evaluări

- Detailed Lesson Plan (2) Grade 9Document23 paginiDetailed Lesson Plan (2) Grade 9Marvin SubionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kelsie Whitehall Adjectives of Quality Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiKelsie Whitehall Adjectives of Quality Lesson Planapi-256152436Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan-Participle AdjectivesDocument2 paginiLesson Plan-Participle Adjectivesapi-257069292Încă nu există evaluări

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocument5 paginiDetailed Lesson PlanNovieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proverb Lesson PlanDocument4 paginiProverb Lesson Planapi-339675038Încă nu există evaluări

- LESSON PLAN Nº1Document2 paginiLESSON PLAN Nº1Lindalu CallejasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic Colleges of Guinobatan, IncDocument6 paginiRepublic Colleges of Guinobatan, IncSalve PetilunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjective Lesson PlanDocument5 paginiAdjective Lesson Planapi-286089068Încă nu există evaluări

- EFL in The Classroom-II (5662) : Diploma TeflDocument20 paginiEFL in The Classroom-II (5662) : Diploma Tefltouheeda zafar100% (1)

- GerundDocument4 paginiGerundLOIDA ALMAZANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prepared By: Analiza V. Responde, SST-I (L-BNHS)Document3 paginiPrepared By: Analiza V. Responde, SST-I (L-BNHS)jellian alcazarenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Active and Passive VoiceDocument2 paginiLesson Plan Active and Passive VoiceGary Osiba100% (1)

- Eng FAL GR 10 I Am Not Talking About That Nou Questions ATDocument3 paginiEng FAL GR 10 I Am Not Talking About That Nou Questions ATSibaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLP Pronoun AntecedentDocument4 paginiDLP Pronoun AntecedentVincent Ian TañaisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Beginners AdjectiveDocument5 paginiLesson Plan Beginners Adjectiveapi-279090350100% (6)

- English Lesson PlanDocument6 paginiEnglish Lesson PlanAnne CayabanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Form HomophonesDocument4 paginiLesson Plan Form Homophonesapi-272398558Încă nu există evaluări

- Libmanan South Central School: III. ProcedureDocument7 paginiLibmanan South Central School: III. ProcedureGemma R. LatamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishDocument6 paginiSample Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishMabelle Escobar ColastreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vowels Lesson PlanDocument2 paginiVowels Lesson Planapi-338180583Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan in English 6Document7 paginiLesson Plan in English 6Lee Jae AnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Friendly Letters Put TogetherDocument6 paginiFriendly Letters Put TogetherMuhammad RusliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adverbs Lesson PlanDocument7 paginiAdverbs Lesson PlanDiego PgÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7 AdveDocument14 paginiA Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7 AdveRauleneÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Semi Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade 7 English:: Coordinating ConjunctionsDocument2 paginiA Semi Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade 7 English:: Coordinating ConjunctionsJESSICA ROSETEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 7 Q3 M2Document29 paginiGrade 7 Q3 M2อนันต์ วรฤทธิกุล100% (1)

- Lesson Plan .Document2 paginiLesson Plan .BLazy Mae MalicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weebly Flipped Classroom Lesson PlanDocument2 paginiWeebly Flipped Classroom Lesson Planapi-380545611Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan For Communicative EnglishDocument3 paginiLesson Plan For Communicative EnglishnuruludetÎncă nu există evaluări

- LESSON: Compound NounsDocument26 paginiLESSON: Compound NounsSusan B. EspirituÎncă nu există evaluări

- Two Too or To PDFDocument4 paginiTwo Too or To PDFAnonymous 1QrjXDzAqdÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in English IIIKrysette GalaDocument9 paginiA Detailed Lesson Plan in English IIIKrysette GalanickeltrimmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- October 7 BAtu Bela Bertangkup LPDocument3 paginiOctober 7 BAtu Bela Bertangkup LPAida AguilarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nouns Lesson Plan-NSC FormatDocument3 paginiNouns Lesson Plan-NSC FormatJordyn BarberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Grade 7 Lesson Plan REGULAR CLASSDocument10 paginiFinal Grade 7 Lesson Plan REGULAR CLASSCarla SheenÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Concrete, Abstract and Collective Nouns": Reading: Writing: Speaking: ListeningDocument4 pagini"Concrete, Abstract and Collective Nouns": Reading: Writing: Speaking: ListeningHoney Let PanganibanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conjunction Lesson Plan For DemoDocument12 paginiConjunction Lesson Plan For Demoilias mohaymenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kinds of Sentences According To StructureDocument12 paginiKinds of Sentences According To StructureSmylene MalaitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishDocument17 paginiA Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishClinton ZamoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- WEEK 2 ENGLISH 5 Compound Sentence Showing Cause and EffectDocument10 paginiWEEK 2 ENGLISH 5 Compound Sentence Showing Cause and EffectHannah DingalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan 1Document2 paginiLesson Plan 1api-488541223Încă nu există evaluări

- Correlative Conjunctions DLPDocument2 paginiCorrelative Conjunctions DLPMylene AlviarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan of Active and Passive VoiceDocument6 paginiLesson Plan of Active and Passive Voicehero zamruddynÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Detailed Daily Lesson Plan in English 8Document8 paginiA Detailed Daily Lesson Plan in English 8Charmaine Grace Dung-aoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Idioms LessonDocument5 paginiIdioms Lessonapi-307337824Încă nu există evaluări

- Homophone Lesson Plan WeeblyDocument8 paginiHomophone Lesson Plan Weeblyapi-306937002Încă nu există evaluări

- A Compound Personal PronounDocument1 paginăA Compound Personal PronounClarissa CajucomÎncă nu există evaluări

- English: Active and Passive VoiceDocument10 paginiEnglish: Active and Passive VoiceEthan Lance CuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiSample Lesson PlanClimfel Mariz Tirol Datoon67% (3)

- Quotations Lesson PlanDocument5 paginiQuotations Lesson Planapi-313105261Încă nu există evaluări

- Dialogue Lesson PlanDocument4 paginiDialogue Lesson PlanTaylorÎncă nu există evaluări

- SEMI-DETAILED-DLP-G9-Active and Passive VoiceDocument5 paginiSEMI-DETAILED-DLP-G9-Active and Passive VoiceChello Ann AsuncionÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2-in-1 Book Series: Teacher King’s English Beginner Course Book 1 & English Speaking Course Book 1 - Chinese EditionDe la Everand2-in-1 Book Series: Teacher King’s English Beginner Course Book 1 & English Speaking Course Book 1 - Chinese EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- No Mistakes Grammar Bites, Volume XXVII, “Subject and Verb Agreement” and “Capitalization Rules”De la EverandNo Mistakes Grammar Bites, Volume XXVII, “Subject and Verb Agreement” and “Capitalization Rules”Încă nu există evaluări

- Reading Guide There Will Come Soft RainsDocument11 paginiReading Guide There Will Come Soft Rainsapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Lin Lessonplans FinalDocument94 paginiLin Lessonplans Finalapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Lin Introweek Day3Document5 paginiLin Introweek Day3api-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Lin UnitreflectionDocument4 paginiLin Unitreflectionapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- One World PosterDocument1 paginăOne World Posterapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Lin Introweek Day1Document6 paginiLin Introweek Day1api-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Lin Introweek Day2Document6 paginiLin Introweek Day2api-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Unitobjectives WebsiteDocument2 paginiUnitobjectives Websiteapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Lin Summative Rubric FinalDocument3 paginiLin Summative Rubric Finalapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Lin Summative Handout FinalDocument2 paginiLin Summative Handout Finalapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Gradingplan FinalDocument1 paginăGradingplan Finalapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Email RequestsDocument4 paginiEmail Requestsapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- We Do Language ImageDocument1 paginăWe Do Language Imageapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- 45 VparttwoDocument60 pagini45 Vparttwoapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Ell Best Practices VFDocument4 paginiEll Best Practices VFapi-301715107Încă nu există evaluări

- Wwork 1117Document9 paginiWwork 1117api-268677723Încă nu există evaluări

- 2013 Journal - Hickey and Lewis - Morphology 101Document16 pagini2013 Journal - Hickey and Lewis - Morphology 101api-264118869Încă nu există evaluări

- AppendixJ COT T1-3.final PDFDocument2 paginiAppendixJ COT T1-3.final PDFRichel CrowelÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-2013 Quick Reference Guide - Faculty/Staff EditionDocument60 pagini2012-2013 Quick Reference Guide - Faculty/Staff EditionBenLippenSchoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workbook Facilitation SkillsDocument75 paginiWorkbook Facilitation Skillsjack sparow100% (2)

- KindergartenDocument18 paginiKindergartenTejas Jasani43% (7)

- Francis Bacon, "Of Travel": From The Essayes, or Counsels Civill and Morall ( )Document2 paginiFrancis Bacon, "Of Travel": From The Essayes, or Counsels Civill and Morall ( )Somapti DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment PortfoliosDocument2 paginiAssessment PortfoliosNoor HidayahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan LiA Yr3Document4 paginiLesson Plan LiA Yr3Azrawati AbdullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hibbing (2003) Visualizing For Struggling ReadersDocument14 paginiHibbing (2003) Visualizing For Struggling ReadersbogdanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- KHDA - St. Mary Catholic High School Dubai 2016-2017Document25 paginiKHDA - St. Mary Catholic High School Dubai 2016-2017Edarabia.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- MidwestDocument3 paginiMidwestapi-313401144Încă nu există evaluări

- Working With Cefr Can-Do Statements v2 1 PDFDocument154 paginiWorking With Cefr Can-Do Statements v2 1 PDFviersiebenÎncă nu există evaluări

- P 21 Early Childhood GuideDocument12 paginiP 21 Early Childhood GuideAlex AlexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jane Eyre SummaryDocument2 paginiJane Eyre Summaryمستر محمد علي100% (1)

- Daily Lesson Plan in Reading and WritingDocument5 paginiDaily Lesson Plan in Reading and WritingConnieRoseRamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Department of Education: School Initiative Consultation Observation Tool (Sicot)Document2 paginiDepartment of Education: School Initiative Consultation Observation Tool (Sicot)Danilo dela RosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prairie Modeling Lesson PlanDocument4 paginiPrairie Modeling Lesson PlanNikki LevineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Humanistic ApproachDocument20 paginiHumanistic ApproachAnonymous FgUW11Încă nu există evaluări

- RAFT Lesson Plan SequenceDocument5 paginiRAFT Lesson Plan Sequencetrice2014Încă nu există evaluări

- The Oral Reading Fluency PDFDocument11 paginiThe Oral Reading Fluency PDFDIVINA D QUINTANA100% (1)

- Nut 118 Final ProjectDocument4 paginiNut 118 Final Projectapi-347518401Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan in Field StudyDocument5 paginiLesson Plan in Field Studyjunaida saripadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dribbling and Shooting Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiDribbling and Shooting Lesson Planapi-353103487Încă nu există evaluări

- Imb Math Lesson PlanDocument4 paginiImb Math Lesson Planapi-379184040100% (1)

- Biqiche A - 2Document63 paginiBiqiche A - 2Mrani SanaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taking InventoryDocument4 paginiTaking InventoryMaura CrossinÎncă nu există evaluări

- E-Litaracy Narrative 2nd Draft FeedbackDocument3 paginiE-Litaracy Narrative 2nd Draft Feedbackapi-271973532Încă nu există evaluări

- Teaching Culture Through AdvertisingDocument4 paginiTeaching Culture Through Advertisingana.moutinho1170Încă nu există evaluări