Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Leeway Space and The Resolution of Crowding in The Mixed Dentition.

Încărcat de

Jose CollazosTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Leeway Space and The Resolution of Crowding in The Mixed Dentition.

Încărcat de

Jose CollazosDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Leeway Space and the Resolution of

Crowding in the Mixed Dentmon

Anthony A. Gianelly

The leeway space provides adequate space to resolve crowding that is

present in the mixed dentition in the majority of individuals. This space can

be maintained by preserving arch length with a lingual arch as the primary

teeth begin to exfoliate, unless conditions such as the premature loss of a

primary canine require earlier intervention. A lip bumper can also be inserted after the eruption of the first premolars to preserve arch length.

Copyright 1995 by W.B. Saunders Company

rowding, which can be present in all classes

o f malocclusions, is p r o b a b l y the most

c o m m o n p r o b l e m r e s o l v e d by o r t h o d o n t i c

treatment. T o align a crowded dentition, space

is necessary. In the mixed dentition, one mechanism fbr gaining space for alignment is to

preserve the leeway space, which can be as

m u c h as 4.3 ram. ~ This g e n e r o u s space may be

one reason why crowding in the mixed dentition becomes less p r o n o u n c e d with the develo p m e n t o f the p e r m a n e n t dentition. For example, Moorrees and Chada indicated that 1 to 2

m m o f crowding is a characteristic feature in

individuals who d e m o n s t r a t e n o r m a l alignm e n t in the p e r m a n e n t dentition.

This observation raises a series o f interesting questions, such as what is the incidence of

crowding in the mixed dentition, and how often can the leeway space p r o v i d e a d e q u a t e

space to resolve this crowding? (Since lower

arch conditions dictate the strategy for maxillary arch treatment, only the changes in the

lower arch will be discussed.)

T o answer these questions, the mandibular

models o f t 00 patients in the mixed dentition

stage o f d e v e l o p m e n t were evaluated, in the

sample, crowding, which a v e r a g e d 4.5 ram,

was p r e s e n t in 85 o f the 100 individuals. ~

From the Department of Orthodontics, Boston University

School of Graduate Dentist~, Boston, MA.

Address correspondence to Anthony A. Gianelly, DMD, PhD,

MD, Professor and Chairman, Department of Orthodontics, Boston University School of Graduate Dentist~7, 100 E Newton St,

Boston, MA 02118.

Copyright 1995 by' W.B. Saunders Company

1073-8746/95/0103-000655.00/0

188

Crowding was d e f i n e d as a tooth-size/arch-size

discrepancy and was d e t e r m i n e d by c o m p a r i n g

the mesiodistal diameters o f the p r i m a r y and

p e r m a n e n t teeth to arch p e r i m e t e r . W h e n

teeth were absent, their size was estimated

from their antimere, when present, or f r o m

data provided by Moyers et al. 3

W h e n tile leeway space gain was included in

the analysis, only 23 o f the 100 individuals had

insufficient space for alignment. In actuality,

the leeway space represents the "E" space or

the difference between the mesio-distal (m-d)

diameter of the second p r i m a r y molar and the

second p r e m o l a r because the c o m b i n e d m-d

diameter of the primary canine and first molar

( 13.64 ram) is a p p r o x i m a t e l y equal to the combined m-d diameter (13.85 ram) o f the permanent canine and first premolar. :~ This simplifies the usual leeway space calculation.

Thus, with the inclusion o f the E space, 77

o f the 100 patients had a d e q u a t e space in the

arch to a c c o m m o d a t e an aligned dentition.

(The size of u n e r u p t e d p e r m a n e n t teeth was

derived from m-d d i a m e t e r ratios o f p r i m a r y

to c o r r e s p o n d i n g p e r m a n e n t teeth as d e f i n e d

by Moyers et al. :~)

In seven o f tile remaining 23 patients who

would still exhibit a space deficit even after the

inclusion of the E space, tile crowding did not

exceed 2 ram, indicating that 84 out o f 100

subjects would have no m o r e than 2 m m o f

crowding by simply maintaining the E space.

Developmentally, there are t h r e e signs that

are usually described to identify the potential

for crowding in the p e r m a n e n t dentition. 4 T h e

first is the lack o f interdental spaces in the pri-

Seminars in Orthodontics, Vol 1, No 3 (September), 1995: pp 188-194

Leeway Space and Crowding in the M&ed Dentition

189

mary dentition. This sign is not especially reliable since Baume showed that 9 of 16 individuals with no interdental spaces in the primary

dentition did not exhibit crowding in the permanent dentition. 5 The second sign is crowding of the permanent incisors in the mixed

dentition. The third sign is the premature loss

of a primary canine, presumably reflecting inadequate space for the eruption of the lateral

incisor. In crowded conditions, the erupting

lateral incisor "promotes" the resorption of the

root of the primary canine which then exfoliates.

In the group of 100 patients, the most severe crowding was most often associated with

the early loss of a primary canine.

Maintenance of the E Space

Two common appliances used to maintain the

E space are the lingual arch and the lip bumper.

Lingual Arch

Despite its widespread use, comparatively little

is known concerning the effect of lingual arch

placement on the dimensions of the lower

arch. In one of the few reported investigations

on this topic, Singer observed that both arch

length and arch width were increased slightly

by approximately 0.5 mm. 6 Although not a

clinically useful increase, this led him to state,

"It can be seen that the appellation 'passive lingual arch' is a misnomer. Certain basic dental

changes were noted with the use of this appliance. A portion of the effect may be construed

as active movement (distal repositioning of the

molars) although the reason remains obscure."

The results of Singer's study indicated that the

lingual arch should readily maintain the E

space.

Timing of lingual arch placement. The lingual

arch is used when a primary canine is lost prematurely, disrupting the integrity of the dental

arch (Fig 1). The opposite primary canine is

then removed for purposes of symmetry and a

lingual arch is inserted. The function of the

lingual arch at this stage is to prevent the lingual movement (uprighting) of the incisors

with consequent loss of arch length. For in-

Figure 1. (A) Models illustrating early loss of right

primary canine, the removal of the left primary canine, and a lingual arch in place to maintain arch

length. (B) Lingual arch in place as permanent teeth

erupt. Space is available for all teeth.

stance, in a review article on space closure following the early loss of primary teeth, Owen

indicated that most investigators found that

space closure in the lower arch is primarily due

to lingual m o v e m e n t of the Iower incisor

teeth. 7

This raises a question: Why not consider a

serial extraction protocol in patients who lose a

primary canine early, because exfoliation of

the canine represents a space deficit and the

most severe crowding was often noted in patients who lost a primary canine early? This

would avoid the routine insertion of a lingual

arch in these patients. An answer to this question is that the prediction of impending crowding in the permanent dentition is difficult.5'8

For example, Sampson and Richards 8 were

unable to predict incisor crowding from dental

arch parameters and pre-eruptive tooth positions because of unpredictable changes in dental arch width and depth. They advised that,

"Considering the great individual variation,

lack of reliable radiographic and dental arch

190

Anthony A. Gianelly

p a r a m e t e r s o f crowding, a n d the u n e x p e c t e d

tendency for m a n y initially c r o w d e d cases to at

least partially resolve the incisor and/or canine

crowding, e x t r e m e caution should be exercised

in deciding which patients will truly benefit

f r o m serial extraction or early space gaining

procedures."

A n o t h e r reason for not routinely e n d o r s i n g

serial e x t r a c t i o n p r o c e d u r e s w h e n c r o w d i n g

exists in the m i x e d dentition is the observation

by R i n g e n b e r g that there was no d i f f e r e n c e in

t r e a t m e n t results obtained in a g r o u p o f patients t r e a t e d by m e a n s o f serial e x t r a c t i o n

w h e n c o m p a r e d with patients whose t r e a t m e n t

involved conventional p r e m o l a r extractions, l

Active t r e a t m e n t in the serial extraction g r o u p

was a p p r o x i m a t e l y 6 m o n t h s shorter. This indicated that the extraction p r o c e d u r e can be

delayed with little consequence.

Accordingly, a r e c o m r n e n d e d strategy is to

maintain arch length until the first p r e m o l a r s

erupt. At that time, a decision c o n c e r n i n g extraction carl be m a d e with m o r e precision because most d e v e l o p m e n t a l changes will have

occurred, reducing the chance for error.

T h e r e are exceptions to this protocol. O n e is

the p r e s e n c e o f a dehiscence on the labial aspect o f a m a n d i b u l a r incisor tooth. Lingual

m o v e m e n t o f the incisor m i g h t he favorable

since lingual m o v e m e n t is associated with m o r e

p e r i o d o n t a l s u p p o r t ) ) A second exception is

w h e n e r u p t i n g teeth are forced to e r u p t in an

a r e a o f n o n - k e r a t i n i z e d gingiva. In this instance, the p e r i o d o n t a l s u p p o r t o f the tooth

m i g h t be c o m p r o m i s e d d u e to the lack o f keratinized tissue.

A lingual arch is also c o m m o n l y used when

the lateral incisors e r u p t lingual to tile central

incisors (Fig 2). T h e function o f the appliance

is to p r e v e n t loss o f arch length that could oc-

Figure 2. Pre- and post-lingual arch placement.

cur if the lateral incisors m o v e d lingually, followed by the central incisor teeth.

Lip Bumper

T h e lip b u m p e r is an effective appliance for

m a i n t a i n i n g and/or increasing arch length (Fig

3). Any increase in arch length generally reflects both distal m o v e m e n t o f the molars a n d

labial m o v e m e n t o f the incisors, l L.12 Also, most

o f the changes induced by lip b u m p e r treatm e n t occur within the first year. tt As an example, B e r g e r s o n n o t e d that a 1 m m increase

in arch length can routinely be achieved in as

little as 3 m o n t h s o f full-time lip b u m p e r use. 12

Arch width also increases with lip b u m p e r

t r e a t m e n t . 1:~ Cetlin and T e n H o e v e lt d e m o n strated a 2.5 m m increase in intercanine width

a n d a 4 m m gain in i n t e r p r e m o l a r width. T h e y

e m p h a s i z e d that this arch width increase is an

i m p o r t a n t m e c h a n i s m for gaining space for incisor alignment. O t h e r s have o b s e r v e d similar

increases in arch width. 13

Nevant et al l:~ indicated that the type o f lip

b u m p e r and the activation schedule can influence the changes in the m a n d i b u l a r arch obtained with lip b u m p e r therapy. T h e y n o t e d a

larger increases in arch length a n d width when

a lip b u m p e r with an acrylic shield was activated every 4 to 5 weeks when c o m p a r e d with

the changes o b s e r v e d with the use o f a t h i n n e r

lip b u m p e r which was activated every 2 to 3

months. T h u s , m o r e f r e q u e n t activation o f a

lip b u m p e r with a relatively thick labial shield

can e n h a n c e the changes in the dental arch.

T h e arch length and width changes p r o d u c e d

by the lip b u m p e r lead to an increase in arch

circumfi~rence which, in o n e study, a v e r a g e d

4.1 m m . II

Because both the length a n d width o f the

lower dental arch can be increased by b u m p e r

use, w h a t a r e r e a s o n a b l e o b j e c t i v e s o f lip

b u m p e r t r e a t m e n t ? T h i s is a difficult question

to answer because opinions differ c o n c e r n i n g

the stability o f e x p a n d e d m a n d i b u l a r dental

arches. Nance t6 believed that excessive labial

m o v e m e n t o f a n t e r i o r teeth leads to eventual

relapse a n d possible tissue d a m a g e : "to line u p

the teeth in an arch to n o r m a l contact point

relationships . . . is d o w n r i g h t easy p r o v i d e d

one ignores the relationships o f teeth to sup-

Leeway Space and Crowding in the Mixed Dentition

191

Figure 3. (A) Lip bumper in place. (B) Adequate space is present to align the teeth. Arch length was

increased by i mm.

porting bones." His view reiterates the wellknown extraction/non-extraction controversy

between E d w a r d Angle and Calvin Case.

Angle, as r e f e r e n c e d by Bernstein, represented the "new school" o f dentistry which

stressed that n o r m a l occlusion could exist only

when there was a full c o m p l e m e n t of" teeth. 17

Angle also believed that basal b o n e growth

could be induced by functional forces so that

teeth that were m o v e d to a new position would

be s u r r o u n d e d by n e w l y - f o r m e d basal bone.

T h u s , expansion was acceptable and extractions never indicated. In disagreement, Case,

who s u p p o r t e d the views o f the " r a t i o n a l

school," a r g u e d that "new bone c a n n o t be induced to grow b e y o n d its i n h e r e n t size and,

therefore, there are indications for extractions

in certain types o f malocclusions". ~8

One o f the m o r e compelling tales o f ortho d o n t i c f o l k l o r e is the c o n v e r s i o n o f D r

Charles T w e e d f r o m a "non-extractionist" to

an "extractionist." As he recalled, "I practiced

the philosophy of the full c o m p l e m e n t o f teeth

diligently for six years. At the end o f six and a

half years o f o r t h o d o n t i c practice, I called 70%

o f the patients I had treated and classified the

results into successes a n d failures. T o my

amazement, my successes were less than 20%

and my failures m o r e than 80%. ''m

T w e e d t h e n p e r f o r m e d a series o f trials

that, to this day, are unique. H e noted, "In the

beginning, two patients with similar occlusions

were selected, b o t h 13 years old. O n e was

treated with the r e t e n t i o n o f teeth and the

o t h e r had f o u r first premolars r e m o v e d b e f o r e

treatment. After treatment, the results were

most gratifying. Not so for the other, the control case . . . . T h e e x p e r i m e n t was r e p e a t e d ,

doubling the n u m b e r s and the results were

similar. ''2 Finally, a g r o u p o f patients presenting a discrepancy between the size o f teeth and

basal b o n e w e r e selected. T h e y were first

treated by retention o f all teeth. " T h e s e same

patients were r e t r e a t e d after the removal o f all

first premolars. T h e m a n d i b u l a r incisors were

positioned over basal bone. T h e changes in facial esthetics were r e m a r k a b l e and the cases are

now out o f retention and free f r o m any serious

relapse. ''19

T w e e d also stated that w h e n patients with

bimaxillary protrusions were treated by n o n

extraction procedures, "the cases were finished

with the m a n d i b u l a r incisors either tipped or

bodily displaced mesial f r o m their n o r m a l position. Facial aesthetics were bad and the dish a r m o n y o f facial lines increased in direct relation to the extent o f mesial displacement o f

the m a n d i b u l a r incisors f r o m their n o r m a l position. Years o f r e t e n t i o n were futile, and, as a

rule, collapse of the m a n d i b u l a r arch in the

incisor region o c c u r r e d . . . a n d i r r e p a r a b l e

d a m a g e to h a r d and soft investing tissues particularly in the incisal and p r e m o l a r areas, was

the usual a f t e r m a t h o f such treatment. ''19

This b r i e f review indicates that, historically,

the e x p a n d e d lower dental arch was perceived

to be unstable. Since there is confusion, o n e

a p p r o a c h to develop a s o u n d strategy might be

to evaluate comparative outcomes. For example, is the stability o f lower dental arches which

have been e x p a n d e d in the mixed dentition

equal to or greater than the stability o f dental

192

Anthony A. Gianelly

arches which have not been e x p a n d e d ? This

question has been addressed in one study. Little et al c o m p a r e d the stability o f m a n d i b u l a r

dental arches that were e x p a n d e d in the mixed

d e n t i t i o n stage o f d e v e l o p m e n t to resolve

crowding with the stability o f arches that were

not e x p a n d e d . 21 T h e y f o u n d that lower arches

that u n d e r w e n t an increase o f m o r e than 1 m m

in arch length (as m e a s u r e d f r o m one molar to

the mid point between the central incisors to

the o t h e r molar) e x p e r i e n c e d m o r e recrowding when c o m p a r e d with the recrowding noted

when arches were not e x p a n d e d . This observation led the authors to r e c o m m e n d a nonexpansion t r e a t m e n t protocol.

Is the transverse expansion noted with lip

b u m p e r t r e a t m e n t stable? Most emphasis has

been placed on the intercanine dimension because an increase in intercuspid width provides

m o r e space to c o r r e c t c r o w d i n g than o t h e r

transverse changes. Specifically, one estimate is

that 1 m m of intercanine expansion produces a

0.73 m m space that (:an be used t o t alignment,

whereas a 1 m m expansion at the level o f the

molars p r o d u c e s only a 0.25 m m increase in

space. 22

T h e vast majority o f investigators who assessed the long-term stability o f intercanine expansion indicated that expansion o f this zone is

i n h e r e n t l y unstable. 9~-3 in a relevant study

that e m p h a s i z e d stability o f n o n e x t r a c t i o n

t r e a t m e n t results, the intercanine width was increased slightly in t r e a t m e n t f r o m 25.4 m m to

26 ram. After retention, the intercanine width

contracted to 25 ram. Arch length was not increased in this sample. At the start of treatment, arch length was 60 mm, whereas immediately after treatment, it was 60.2 ram. After

retention, arch length was 58 mm, reflecting a

loss o f 2 ram. :~1

T h e inability to enlarge mandilmlar intercanine width p e r m a n e n t l y is probably one of the

most d o c u m e n t e d post t r e a t m e n t changes. Alt h o u g h most o f the i n f o r m a t i o n for this conclusion has been derived by evaluating records

o f patients who were not treated "early" in the

mixed dentition stage o f development, it places

the b u r d e n o f p r o o f to verify the stability of

e x p a n s i o n o f the i n t e r c a n i n e width in the

mixed d e n t i t i o n on those who p r o p o s e this

t r e a t m e n t plan.

T h e findings o f the a b o v e - m e n t i o n e d inves-

tigations indicates that the original arch dimensions are not easily changed. T h e r e f o r e , a

p r u d e n t goal of lip b u m p e r t h e r a p y may be to

gain no m o r e than 1 m m o f arch length and

little arch width, p r o d u c i n g only a 2 m m increase in arch perimeter. If this 2 m m increase

in arch p e r i m e t e r is applied to the 100 individuals previously described, space for alignment

would be available in 84 o f these individuals or

in 84% o f the study group.

Timing of lip bumper placement. T h e author's

p r e f e r e n c e is to insert a lip b u m p e r after the

e r u p t i o n o f the first premolars, particularly

since the primary goal o f b u m p e r placement is

to maintain the E space. I f a decision is m a d e to

increase arch length 1 ram, it can be readily

achieved as the second deciduous molars exfoliate and the second premolars erupt.

As discussed previously, one o f the indications for earlier intervention is the p r e m a t u r e

loss of a primary canine. T h e t r e a t m e n t entails

the removal o f the contralateral p r i m a r y canine and the p l a c e m e n t o f a lingual arch.

W h e n the first p r e m o l a r teeth are erupting, a

space analysis is p e r f o r m e d . I f space is adequate for alignment, the lingual arch is left in

place until all premolars have e r u p t e d . Any

necessary alignment is p e r f o r m e d at this time.

I f there is a space deficit which does not exceed

2 ram, the lingual arch is r e m o v e d when the

first premolars are e r u p t i n g and a lip b u m p e r

inserted. If the shortage o f space is g r e a t e r

than 2 mm, extraction t r e a t m e n t may be the

t r e a t m e n t o f choice unless skeleto-dental conditions contraindicate the extraction o f teeth.

In the study sample, only 16 o f the 100 patients evaluated had crowding in excess o f 2

in hi.

Some might argue that earlier intervention

could also p r o v i d e the space necessary for

these t 6 patients. For example, one strategy is

to e x p a n d the maxilla (RPE) to gain space in

the maxillary arch, and at the same time provoke spontaneous transverse expansion o f the

lower arch. :~9 Although there are too little data

to assess the merits o f this a p p r o a c h adequately, the results o f two studies are not optimistic. S a n d s t r o m et al 3~ e v a l u a t e d t h e

records o f 28 patients whose maxillae were exp a n d e d orthopedically and n o t e d a 2 m m increase in intercanine width which later contracted to only 1.1 ram. Adkins et a134 observed

Leeway Space and Crowding in the Mixed Dentition

that expansion of the lower arch following rapid

palatal expansion did not exceed 0.8 mm.

If "passive" expansion of the lower arch

proves inadequate, there is the possibility of

actively expanding the transverse dimension of

the arch with an appliance such as a Schwartz

plate. 35 As Burstone 36 indicated, the ability to

expand this apical base skeletally is limited

since there is no suture. Therefore any expansion is principally dental in nature. The available data are sparse and equivocal concerning

the ability to expand the lower arch with active

appliances such as the Schwartz plate. Lutz and

Poulton 37 expanded the transverse dimension

of 13 patients in the primary dentition stage of

development and compared the changes to

those observed in 12 control subjects. Expansion was accomplished with removable appliances in 1 1 patients and with fixed appliances

in the remaining two patients. After a threeyear retention period, the patients were followed for another three years. At this time, (6

years posttreatment) the intercanine dimension of the treated sample was not different

from the control group, indicating total relapse of the treatment gain. The findings of

this study are consistent with the many investigations, which concluded that expansion of

the intercanine dimension of the lower arch is

inherently unstable. 23-3

McInaney et al 3s used Crozat appliances to

expand the transverse dimension of the lower

arch in 5-year-old and 6-year-old patients and

retained the changes until all the primary teeth

exfoliated. The intercanine dimension was expanded approximately 5 ram. After retention

was discontinued, the arches remained stable.

In this study there were no control subjects

and data from other published sources were

used to represent the controls. As such, the

actual net e x p a n s i o n ( t r e a t m e n t c h a n g e /

growth change) was not reported. The net expansion would depend on the control sample

chosen for comparison. If the control sample

were comparable to the control group identified by Lutz and Poulton, in which the intercanine width increased 4 to 5 mm, s7 there

would be no net expansion. If, on the other

hand, the comparison involved the control

sample reported by Moorrees and Chada, 1 in

which the intercanine width increased only 2

or m o r e mm as the p e r m a n e n t incisors

erupted, a net gain a p p r o x i m a t i n g 2 mm

193

would be apparent. This lack of correlation between control groups may indicate that arch

width changes that occur in conditions with a

space deficit may be d i f f e r e n t f r o m the

changes noted when there is adequate space

for alignment.

Crowding can be easily resolved by nonextraction treatment procedures, if desired, in at

least 85% of all patients with modest treatment, which can be started in the late mixed

dentition. (One exception previously noted is

the early loss of a primary canine, which requires earlier intervention.) The fate of the

other 15% of the patients is debatable. Should

these be "extraction" type patients (assuming

there are no skeletal contraindications), or

should they be treated earlier, to pursue a nonextraction approach more aggressively? One

view, shared by the author, is that extractions

are the preferable route. A reason for this is

that long-term consequences of early intervention procedures, which are designed to avoid

extraction by producing active and/or passive

expansion of the anterior part of mandibular

dental arch (arch development), are not clear.

Often, the focus is lateral expansion of the intercanine dimension, because this procedure,

as indicated, can readily provide space for

alignment. In this context, arch development is

contrary to the vast majority of available data,

which document the instability of mandibular

intercanine expansion. 23-3 In addition, others

who have discussed and demonstrated posttreatment stability have emphasized that the

mandibular intercanine dimension should not

be expanded during treatment. 39"4

Thus, for those who prefer not to expand

the mandibular dental arch more than 1 mm, a

fundamental difference between extraction

and non-extraction resolution of crowding is

the timing of treatment. Four to five millimeters of incisor crowding in the mixed dentition

stage of development can usually be treated by

nonextraction procedures whose goals include

maintaining the E space. Extraction treatment

is most often necessary to correct 4 to 5 mm of

crowding in the permanent dentition.

References

1. MoorreesCFA,ChadaJM. Availablespace for incisors

during dental development.A growth study based on

physiologicage. Angle Orthod 1965;35:12-22.

194

Anthony ,4. Gia~'~elly

2. Arnold S: Analysis of leeway space in the mixed dentition. Thesis for certification. Boston, Boston University, 1991.

3. Movers RE, van der Linden FPGM, Riolo ML, et al.

Standards of Human OcclusaI Development. Monograph # 5 Craniofacial Growth Series. Ann Harbor,

MI: Center of Human Development, The University

of Michigan, 1976.

4. Gianellv AA. Diagnosis of incipient malocclusions. J

Am Dent Assoc 1969;79:658-661.

5. Baume L. Physiological tooth migration and its significance for the development of occlusion. Part III. The

biogenesis of the successional dentition. J Dent Res

1950;29:338-348.

6. Singer J. T h e effect of the passive lingual arch on the

lower denture. Angle Orthod 1974;44:146-155.

7. Owen DG. The incidence and nature of space closure

following the p r e m a t u r e extraction of deciduous

teeth: A literature survey. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1971 ;59:37-49.

8. Sampson WS, Richards LC. Prediction of mandibular

incisor and canine crowding changes in the mixed

dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1985;88:

47-63.

9. Dorfman HS. Mucogingivat changes resulting from

mandibular incisor tooth movement. Am J Orthod

Dentofaciat Orthop 1978;74:286-297.

I0. Rigenberg AM. Influence of serial extraction on

growth and development of the maxilla and mandible. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1967;53:47-58.

11. Osborn WS, Nanda RS, Currier GF. Mandibular arch

perimeter changes with lip bumper treatment Am J

Orthod DentofaciaI Orthop 1991 ;99:527-532.

12. Bergerson EO. A cephalometric study of the clinical

use of the mandibular labial bumper. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1972 ;61:578-602.

13. Nevant CT, Buschang PH, Alexander RG, et al. Lip

b u m p e r t h e r a p y for gaining arch length. Am J

Orthod Dentofaciat Orthop 1991; I00:330-336.

14. Cetlin, NM, Ten Hoeve ?a. Non extraction treatment.

J Clin Orthod 1983;I7:396-413.

15. Moin K. Buccal shield for mandibular arch expansion.

J Clin Orthod 1988;22:588-590.

I6. Nance H. T h e limitations of orthodontic treatment.

Am J Orthod Oral Surg I947;33:253-301.

I7. Bernstein, L. Edward H. Angle versus Calvin S. Case.

Extraction versus non-extraction. Historical revisionism. Part 1. Am J Orthod DentofaciaI Orthop 1992;

102:464-470.

18. Case CS. T h e question of extraction in Orthodontics.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1964;50:660-691.

19. Tweed CH. Clinical Orthodontics. VoI 1. St Louis,

MO: CV Mosby, 1966.

20. Tweed CH. Indications for extraction of teeth in orthodontic procedures. A m J Orthod Oral Surg I944;30:

405-428.

2I. Little RM, Reidel RA, Stein A. Mandibular arch length

increase during the mixed dentition: Post retention

evaluation of stability and relapse. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1990:97:393-404.

22. Germane N, Lindauer SJ, Rubenstein LK, et al. Increase in arch perimeter due to orthodontic expan-

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

sion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1991 ; 100:421427.

Peak JD. Cuspid stability. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1956:42:608-614.

Bishara SE, Chada JM, Potter RB. Stability of intercanine width, overbite and overjet correction. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1973;63:588-595.

Shapiro PA. Mandibular dental arch and dimension.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1974;66:58-70.

Kuftinec MM. Effect of edgewise treatment and retention of mandibular incisors. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1975;68:316-22.

EI-Mangoury NH. Orthodontic relapse in subjects

with varying degrees of anteroposterior and vertical

dysplasia. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1979;75:

548-61.

Sondhi A, Cleall JF, BeGole EA. Dimensional changes

in the arches of orthodontically treated cases. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop I980;77:60-74.

Little RM, Wallen TR, ReideI RA. Stability and relapse

of mandibular anterior alignment-first premolar extraction cases treated by conventional edgewise orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1981;80:

349-65.

Uhde MD, Sadowsky C, BeGole EA. Long term stability of" dental relationships after orthodontic treatment.

Angle Orthod 1983;53:240-252.

Glenn G, Sinclair PM, Alexander RG. Nonextraction

orthodontic therapy: Post treatment dental and skeletal stability. Am J Ortho Dentofacial Orthop 1987;

92:321-28.

Haas A. Long term post treatment evaluation of rapid

palatal expansion. Angle Orthod 1980;50: 189-217.

Sandstrom RA, Klapper L, Papaconstantinou S. Expansion of the lower arch concurrent with rapid maxillary expansion. Am j Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

1988;94:296-302.

Adkins MA, Nanda RS, Currier GF. Arch perimeter

changes on rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1990;97:194-199.

McNamara JA Jr, Brudon WL. Orthodontic and orthopedic treatment in the mixed dentition. Ann Arbor, MI: Needham Press, 1993:78-80.

Burstone CJ. Perspective on orthodontic stability. In:

Nanda R, Burstone CJ, editors. Retention and Stability in Orthodontics. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1993:4561.

Lutz HD, Pouhon DR. Stability of dental arch expansion in the deciduous dentition. Angle Orthod 1985;

55:299-315.

McInanev JB, Adams RM, Freeman MM. A nonextraction approach to crowded dentitions in young

children: Early recognition and treatment. J Am Dent

Assoc 1980;101:251-57.

Gorman JC. The effects of premolar extraction on the

long term stability of the mandibular incisors. In:

Nanda R, Burstone CJ, editors. Retention and Stability in Orthodontics. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1993:8196.

Alexander RG. T r e a t m e n t and retention for long

term stabilitv. In: Nanda R, Burstone CJ, editors. Retention and Stability in Orthodontics. Philadelphia:

Saunders, 1993:115-134.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Crossbite PosteriorDocument11 paginiCrossbite PosteriorrohmatuwidyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BCA Urine Test Results - Sheriff HutchinsonDocument1 paginăBCA Urine Test Results - Sheriff HutchinsonDan EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABGD Written Study Questions 2007Document291 paginiABGD Written Study Questions 2007velangni100% (1)

- ABGD Written Study Questions 2007Document291 paginiABGD Written Study Questions 2007Almehey NaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Let S Be Your Guide-PoundDocument8 paginiLet S Be Your Guide-PoundFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pascal Magne-Anatomic Crown Widthlength Ratios of Unworn and Worn Maxillary TeethDocument10 paginiPascal Magne-Anatomic Crown Widthlength Ratios of Unworn and Worn Maxillary TeethCaleb LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romano - Orto LingualDocument202 paginiRomano - Orto LingualJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transverse Dimension Andlong-Term Stability Robert L Vanarsdall JRDocument10 paginiTransverse Dimension Andlong-Term Stability Robert L Vanarsdall JRMa Lyn GabayeronÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Pendulum Appliance For Class II Non-Compliance TherapyDocument6 paginiThe Pendulum Appliance For Class II Non-Compliance TherapyJose Collazos100% (1)

- Personal RelationshipDocument19 paginiPersonal RelationshipVirginia HelzainkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maxillary Transverse DeficiencyDocument4 paginiMaxillary Transverse DeficiencyCarlos Alberto CastañedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PDFDocument216 paginiPDFJomana JomanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Missing Lateral Incisors Treatment ApproachesDocument17 paginiMissing Lateral Incisors Treatment ApproachesAvneet MalikÎncă nu există evaluări

- ED 104 Module 1 Vision, Policy, Goal and Objectives of Special EducationDocument12 paginiED 104 Module 1 Vision, Policy, Goal and Objectives of Special EducationAngela Diaz100% (9)

- Idealism in EducationDocument9 paginiIdealism in EducationAnonymous doCtd0IJDN100% (1)

- Evolution of Esthetic Considerations in OrthodonticsDocument6 paginiEvolution of Esthetic Considerations in OrthodonticsJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Serial Extractions Review of Dental Crowding TreatmentDocument8 paginiSerial Extractions Review of Dental Crowding TreatmentJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPACE ANALYSIS AND MANAGEMENTDocument28 paginiSPACE ANALYSIS AND MANAGEMENTReena Chacko100% (1)

- The Nance Lingual Arch: An Auxiliary Device in Solving Lower Anterior CrowdingDocument5 paginiThe Nance Lingual Arch: An Auxiliary Device in Solving Lower Anterior CrowdingTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarÎncă nu există evaluări

- ملخصDocument11 paginiملخصhgfdsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gingival Recession Related To Removable Partial Dentures in Older PatientsDocument6 paginiGingival Recession Related To Removable Partial Dentures in Older Patientssara luciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Passive lower lingual arch manages anterior mandibular crowdingDocument6 paginiPassive lower lingual arch manages anterior mandibular crowdingManda JoanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pucciarelli2018 PDFDocument4 paginiPucciarelli2018 PDFAkanksha MahajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dentofacial Changes From Fan-Type Rapid Maxillary Expansion Vs Traditional Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Early Mixed Dentition A Prospective Clinical TrialDocument9 paginiDentofacial Changes From Fan-Type Rapid Maxillary Expansion Vs Traditional Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Early Mixed Dentition A Prospective Clinical TrialMirza GlusacÎncă nu există evaluări

- CLASSIC ARTICLE Clinical Measurement and EvaluationDocument5 paginiCLASSIC ARTICLE Clinical Measurement and EvaluationJesusCordoba100% (2)

- Literature ReviewDocument3 paginiLiterature ReviewPuteri NazirahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Space in the Mixed DentitionDocument11 paginiManaging Space in the Mixed Dentitionreal_septiady_madrid3532Încă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of A Maxillary Lip Bumper On Tooth Positions: Rudolf Häsler and Bengt IngervallDocument8 paginiThe Effect of A Maxillary Lip Bumper On Tooth Positions: Rudolf Häsler and Bengt IngervallCalin CristianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pulp Space Anatomy and Access CavitiesDocument8 paginiPulp Space Anatomy and Access CavitiesMustafa SameerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lib BumpersDocument3 paginiLib BumpersDaniel Garcia von BorstelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kokich CaninosDocument6 paginiKokich CaninosMercedes RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tooth Morphology and Access Cavity PreparationDocument232 paginiTooth Morphology and Access Cavity Preparationusmanhameed8467% (3)

- Is Orthodontic Treatment Without Premolar Extractions Always Non-Extraction Treatment?Document6 paginiIs Orthodontic Treatment Without Premolar Extractions Always Non-Extraction Treatment?119892020Încă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of The Treatment of Impacted Canines During A Twenty-Year PeriodDocument4 paginiAnalysis of The Treatment of Impacted Canines During A Twenty-Year PeriodgekdiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Master Dentistry 2Document5 paginiMaster Dentistry 2Laili Nurul IslamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Implant Surgical AnatomyDocument14 paginiImplant Surgical AnatomyKo YotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exostosis MandibularDocument6 paginiExostosis MandibularCOne Gomez LinarteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dental RX FelineDocument22 paginiDental RX FelinecarlosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Kinetics of Anterior Tooth DisplayDocument3 paginiThe Kinetics of Anterior Tooth DisplayYu Yu Victor Chien100% (1)

- Endodontic Management of Three-Rooted Maxillary First Premolar-A Case ReportDocument3 paginiEndodontic Management of Three-Rooted Maxillary First Premolar-A Case ReportDanish NasirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Ilmu Konservasi Gigi: PSA Pada Supernumery RootDocument6 paginiJurnal Ilmu Konservasi Gigi: PSA Pada Supernumery RootAchmad Zam Zam AghazyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laureys 2013 Journal of EndodonticsDocument5 paginiLaureys 2013 Journal of EndodonticsRimy SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- JOE - MorphologicalMeas - PulpOut BurDocument3 paginiJOE - MorphologicalMeas - PulpOut BurGabriela CiobanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impacted Maxillary Canines-A Review. - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 101-159, 1992 PDFDocument13 paginiImpacted Maxillary Canines-A Review. - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 101-159, 1992 PDFPia ContrerasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S0002817714656762 MainDocument5 pagini1 s2.0 S0002817714656762 MainDANTE DELEGUERYÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S001185321100005X MainDocument17 pagini1 s2.0 S001185321100005X MainMohammed OmoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mandibuiar Speech Envelope in Subjects With and Without Incisai Tooth WearDocument6 paginiThe Mandibuiar Speech Envelope in Subjects With and Without Incisai Tooth Wearjinny1_0Încă nu există evaluări

- Position of Teeth in Edentulous Maxilla DeterminedDocument6 paginiPosition of Teeth in Edentulous Maxilla DeterminedShafqat HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extractions in OrthodonticsDocument6 paginiExtractions in OrthodonticsZubair AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 Pattern of Maxillary and Mandibular Proximal Enamel Thickness at The Contact Area of The Permanent Dentition From First Molar To First MolarDocument10 pagini2015 Pattern of Maxillary and Mandibular Proximal Enamel Thickness at The Contact Area of The Permanent Dentition From First Molar To First MolarElías Enrique MartínezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space MaintenanceDocument17 paginiSpace MaintenanceAla StarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lingual-Keys For SuccessDocument8 paginiLingual-Keys For SuccessGoutam NookalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Serial ExtractionDocument38 paginiSerial ExtractionRamy HanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Longitudinal Evaluation of Extraction Versus Nonextraction Treatment With Special Reference To The Posttreatment Irregularity of The Lower IncisorsDocument11 paginiA Longitudinal Evaluation of Extraction Versus Nonextraction Treatment With Special Reference To The Posttreatment Irregularity of The Lower IncisorsBeatriz ChilenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Third Molar Autotransplant Planning With A Tooth Replica. A Year of Follow-Up Case ReportDocument6 paginiThird Molar Autotransplant Planning With A Tooth Replica. A Year of Follow-Up Case ReportAlÎncă nu există evaluări

- En Masse Retraction and Two-Step Retraction of Maxillary Anterior Teeth in Adult Class I WomenDocument6 paginiEn Masse Retraction and Two-Step Retraction of Maxillary Anterior Teeth in Adult Class I WomenMihaela BejanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 Space MaintenanceDocument17 paginiChapter 4 Space MaintenanceMarwan AlamriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Periodontal Dictates For Esthetic Ceramometal Crowns: R - Sheldon Stein, DMDDocument11 paginiPeriodontal Dictates For Esthetic Ceramometal Crowns: R - Sheldon Stein, DMDadambear213Încă nu există evaluări

- Anesthetic Technique For Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block: A New ApproachDocument5 paginiAnesthetic Technique For Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block: A New ApproachIonela AlexandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparison of Skeletal and Dental Changes Between 2-Point and 4-Point Rapid PalatalDocument8 paginiComparison of Skeletal and Dental Changes Between 2-Point and 4-Point Rapid PalatalManena RivoltaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Num36 Prerequisities in Serial Extraction PDFDocument7 paginiNum36 Prerequisities in Serial Extraction PDFMichele MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Displaced Lower Third Molar: A Literature Review and Suggestions For ManagementDocument5 paginiThe Displaced Lower Third Molar: A Literature Review and Suggestions For ManagementRajat GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morphological Changes in the Denture Bearing Area After Tooth ExtractionDocument11 paginiMorphological Changes in the Denture Bearing Area After Tooth ExtractionEugenStanciuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pulp Analysis Primary MolarDocument6 paginiPulp Analysis Primary MolarScm MassielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endoguide 5676Document5 paginiEndoguide 5676Ruchi ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shortened Dental Arches and Oral Function: Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 1981, Volume 8, Pages 457-462Document7 paginiShortened Dental Arches and Oral Function: Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 1981, Volume 8, Pages 457-462praveen rajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short ImplantsDe la EverandShort ImplantsBoyd J. TomasettiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of 8 Hour Intermittent Orthodontic Force On Osteoclasts and Rooot ResorptionDocument8 paginiEffect of 8 Hour Intermittent Orthodontic Force On Osteoclasts and Rooot ResorptionJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Optium Force Magnitude For Orthodontic Tooth Movement, A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument7 paginiOptium Force Magnitude For Orthodontic Tooth Movement, A Systematic Literature ReviewJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Change in The Gingival Fluid Volume During Maxillary Canine RetractionDocument6 paginiChange in The Gingival Fluid Volume During Maxillary Canine RetractionJose Collazos100% (1)

- Evaluation of The Risk of Root Resorption During Orthodontic Treatment, A Study of Upper Incisors.Document9 paginiEvaluation of The Risk of Root Resorption During Orthodontic Treatment, A Study of Upper Incisors.Jose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Long - and Short-Term Effects of Headgear TractionDocument10 paginiLong - and Short-Term Effects of Headgear TractionMohammed HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Long - and Short-Term Effects of Headgear TractionDocument10 paginiLong - and Short-Term Effects of Headgear TractionMohammed HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness and Duration of Orthodontic Treatment in Adults and AdolescentsDocument4 paginiEffectiveness and Duration of Orthodontic Treatment in Adults and AdolescentsJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apical Root Resorption of Incisors After Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Maxillary Canines, Radiographic StudyDocument9 paginiApical Root Resorption of Incisors After Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Maxillary Canines, Radiographic StudyJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Utility of Panoramic Radiography For Identification of The Pubertal Growth PeriodDocument7 paginiUtility of Panoramic Radiography For Identification of The Pubertal Growth PeriodJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- MGBM System, New Protocol For Class II Non Extraction Treatment Without CooperationDocument14 paginiMGBM System, New Protocol For Class II Non Extraction Treatment Without CooperationJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Questions of Extraction (Ortodoncia)Document32 paginiThe Questions of Extraction (Ortodoncia)Jose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orthodontic Therapy and Gingival Recession, A Systematic Review PDFDocument15 paginiOrthodontic Therapy and Gingival Recession, A Systematic Review PDFJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Corticotomy - Facilitated Orthodontics and Piezocision in Rapid Canine RetractionDocument8 paginiEvaluation of Corticotomy - Facilitated Orthodontics and Piezocision in Rapid Canine RetractionJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aparato Funcional Fijo Con Aparatología Multibracket (Revisión Sistemática)Document13 paginiAparato Funcional Fijo Con Aparatología Multibracket (Revisión Sistemática)Jose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Long-Term Stability of SkeletalDocument11 paginiEvaluation of Long-Term Stability of SkeletalJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Clinical Application A Tooth-Size Analysis: IntroductiokDocument26 paginiThe Clinical Application A Tooth-Size Analysis: Introductiokapi-26468957Încă nu există evaluări

- Bone Ceramic Graft Regenerates Aleveolar Defects But Slows Orthodontic Tooth Movement With Less Root ResorptionDocument10 paginiBone Ceramic Graft Regenerates Aleveolar Defects But Slows Orthodontic Tooth Movement With Less Root ResorptionJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prevalence of Malocclusion Among Adolescents in Ibadan, NigeriaDocument4 paginiPrevalence of Malocclusion Among Adolescents in Ibadan, NigeriaJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prediction of Mandibular Growth Rotation, Assessment of The Skieller, Bjork and Linde-Hansen Method PDFDocument9 paginiPrediction of Mandibular Growth Rotation, Assessment of The Skieller, Bjork and Linde-Hansen Method PDFJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- CLINICAL AID In-Office Manufacturing of Quad Helix Appliances - JCO-OnLINEDocument2 paginiCLINICAL AID In-Office Manufacturing of Quad Helix Appliances - JCO-OnLINEJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Premolar Extractions On Bolton Overall Ratios and Tooth-Size Discrepancies in Japanese Orthodontic PopulationDocument7 paginiEffects of Premolar Extractions On Bolton Overall Ratios and Tooth-Size Discrepancies in Japanese Orthodontic PopulationJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orthodontic Treatment Changes of Chin PositionDocument10 paginiOrthodontic Treatment Changes of Chin PositionJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of The Masseter Muscle in Different Facial Morphological PatternsDocument8 paginiMagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of The Masseter Muscle in Different Facial Morphological PatternsJose CollazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activity Who Wants To Be A MillionaireDocument30 paginiActivity Who Wants To Be A MillionaireNeil Jasper DucutÎncă nu există evaluări

- PDF Title Page For PrintingDocument11 paginiPDF Title Page For PrintingAngela Mari ElepongaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Perception of Community Towards The ImplementedDocument7 paginiThe Perception of Community Towards The ImplementedRia-Nette CayumoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rodriguez 2018Document5 paginiRodriguez 2018Heine MüllerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Everything You Need to Know About FootballDocument4 paginiEverything You Need to Know About Football6 Flaze 6Încă nu există evaluări

- Rosette Forming Glioneuronal Tumor (RFGNT) Extremely Rare Entity - CopieDocument16 paginiRosette Forming Glioneuronal Tumor (RFGNT) Extremely Rare Entity - CopieCalin M.Încă nu există evaluări

- Maritex Aquapure Bearing Material SDSDocument5 paginiMaritex Aquapure Bearing Material SDSHovanTaTarianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sensory Evaluation of Pumpkin Ice Cream with Red Dragon FruitDocument7 paginiSensory Evaluation of Pumpkin Ice Cream with Red Dragon FruitHaditama IndrascyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management & Marketing: Post-COVID-19 Management Guidelines For Orthodontic PracticesDocument5 paginiManagement & Marketing: Post-COVID-19 Management Guidelines For Orthodontic Practicesdruzair007Încă nu există evaluări

- InSimu ReportDocument10 paginiInSimu ReportCiprian CeianÎncă nu există evaluări

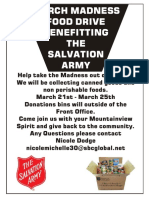

- March Madness Food DriveDocument1 paginăMarch Madness Food Driveapi-234164294Încă nu există evaluări

- A.bsfhsjsjsjgsg-WPS OfficeDocument3 paginiA.bsfhsjsjsjgsg-WPS OfficeGJ MagbanuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filipino Teacher: G. Enrile Contact# 09661888404: Modyul 3 F10PN-Ic-d-64Document7 paginiFilipino Teacher: G. Enrile Contact# 09661888404: Modyul 3 F10PN-Ic-d-64Johnry Guzon ColmenaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhatnagar International School Paschim Vihar Holidays Homework 2018-19 Vii FormDocument5 paginiBhatnagar International School Paschim Vihar Holidays Homework 2018-19 Vii Formkapil chopraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Case Week 3Document25 paginiFamily Case Week 3Luiezt BernardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Examination & Diagnosis of Edentulous Patients: Presented By: Dr. Jehan Dordi 1 Yr. MdsDocument159 paginiExamination & Diagnosis of Edentulous Patients: Presented By: Dr. Jehan Dordi 1 Yr. MdsAkanksha MahajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Computer-Based Scenario Biochemistry: How To Read Bloods?Document66 paginiComputer-Based Scenario Biochemistry: How To Read Bloods?Haytham KhalifaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orthodontic Treatment Needs in Adolescents Aged 13-15 Years Using Orthodontic Treatment Needs IndicatorsDocument7 paginiOrthodontic Treatment Needs in Adolescents Aged 13-15 Years Using Orthodontic Treatment Needs IndicatorsTitis NlgÎncă nu există evaluări

- SCI 1 With Legal Medicine: Learning OutcomesDocument9 paginiSCI 1 With Legal Medicine: Learning OutcomesJohn Paul Artiola RapalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Association of Screen Time With Academic Performance and Behaviour Among Primary School Children of Kandy District Sri LankaDocument6 paginiAssociation of Screen Time With Academic Performance and Behaviour Among Primary School Children of Kandy District Sri LankaAira RamosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals of Nursing (Lab)Document1 paginăFundamentals of Nursing (Lab)Mervi SarsonasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 2 - Nutritional Care PlanDocument11 paginiGroup 2 - Nutritional Care PlanBea ConcepcionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ward RoundDocument3 paginiWard RoundAdaha AngelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adhd Interventions For Parents PDFDocument1 paginăAdhd Interventions For Parents PDFCarol Moreira PsiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Screenshot 2024-01-14 at 1.32.49 PMDocument10 paginiScreenshot 2024-01-14 at 1.32.49 PMMaureen KathureÎncă nu există evaluări