Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Essay 4

Încărcat de

Danika Barker0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

52 vizualizări16 paginiDover wilson: Hamlet's sudden change of tone in Nunnery Scene has long been controversial. He says one theory is that he overhears the end of the plot to "loose" Ophelia to him. But this theory is untenable for two reasons: first, it depends on an unjustifiable speculation, he says.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDover wilson: Hamlet's sudden change of tone in Nunnery Scene has long been controversial. He says one theory is that he overhears the end of the plot to "loose" Ophelia to him. But this theory is untenable for two reasons: first, it depends on an unjustifiable speculation, he says.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

52 vizualizări16 paginiEssay 4

Încărcat de

Danika BarkerDover wilson: Hamlet's sudden change of tone in Nunnery Scene has long been controversial. He says one theory is that he overhears the end of the plot to "loose" Ophelia to him. But this theory is untenable for two reasons: first, it depends on an unjustifiable speculation, he says.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 16

Hamlet’s Cue For Passion

in the Nunnery Scene

ArTHUR NoeL Kincaip

Tie reason for Hamlet's abrupt change of tone in the nunnery scene

(ULi) and the apparent alteration of his attitude toward Ophelia at or just

after the line “Where's your father?” have long been the subject of

controversy. Various interpretations have been put forward, many of them

farfetched.* Two of the most famous and most favored are those of Dover

Wilson and Granville-Barker.

Dover Wilson? constructs an elaborate device—which is not in any de-

tail justified in the existing texts—by which Hamlet overhears the end of

the plot to “loose” Ophelia to him. This necessitates Hamlet's being given

a false entrance on the inner stage in ILii a few lines earlier than prescribed

by the usual stage direction and by Gertrude’s comment on his entrance.

Having entered early, he must overhear the conclusion of the plot, pause,

compose his features, and come forward at the appropriate time. This

theory is untenable for two reasons. First, it depends on an unjustifiable

speculation: that two entrances (one on the inner stage, one on the fore-

stage) were given Hamlet in Shakespeare's manuscript and that the compos-

itor, mistaking the former for a prompt, omitted it, thus leaving us in

Folio and Quarto with only the entrance at line 167, where Gertrude re-

marks it. Second, it is doubtful whether on the large Elizabethan stage a

movement so subtle as a false entrance would have been possible.

Nowhere does Hamlet tell us he has overheard anything. We must be

wary of assuming that a character overhears unless he clearly informs or

shows us that he does. The techniques by which Shakespeare sets up

scenes of overhearing can be seen in numerous cases, some of the most

famous being in Love’s Labor's Lost (IV.ii), Midsummer Night's Dream (Ili

and ILL.i), Romeo and Juliet (I1.ii), Richard If (iILiv), Much Ado (ILi, and IILi),

Measure for Measure (IIl.i), Othello (IV.i), Troilus (V.ii), Macbeth (V.i), and

Tempest (IIL.i). In Titus (V.i) and As You Like It (Ili), people report what

they have overheard. That Timon has overheard the Poet and Painter in

V.i is reflected in his subsequent behavior to them. But he has let the au-

dience know, by his asides commenting directly on what they say, that he

is overhearing these characters. In Hamlet we have three undisputed over-

hearings with which to compare this conjectural one: Claudius overhears

99

100 Arruur Nort Kincarp

once (III.i) and Polonius twice (IIL.i and ILiv). In addition, Hamlet at one

point (IIL iii), though not actually overhearing, views Claudius without the

latter’s knowledge. The device of overhearing or overseeing seems to be

one of Shakespeare’s favorite tricks, and the techniques he uses to convey

it are invariably clear to the audience.

Dover Wilson nevertheless proceeds with assurance: the plot to use

Ophelia as decoy would have been flawless “if the subject of it had not

happened to overhear the whole plot the day before” (p. 126). For in the

midst of the scene with Ophelia, Hamlet suddenly remembers what he had

casually overheard “the day before," and from that moment on, alll his ut-

terances are directed at the eavesdroppers. The moment this theory favours

for his realization occurs just before “Ha, ha! are you honest?”> Dover Wil-

son commends his explanation to us because it “happily rids us of the trad-

itional stage-business of Polonius’ exposing himself to the eye of Hamlet

and the audience,” which he considers “a trick crude and inadequate,” for

it shows Polonius as far too clumsy and, though it might suffice for a mod-

ern audience familiar with the play, would probably not have served for

Elizabethans (pp. 133ff.).

Granville-Barker’s theory, so called for convenience (it derives from

stage tradition originating in the 1820s‘), is that Hamlet during his conver-

sation with Ophelia

Suddenly becomes aware that they are being watched; and can

he resist the conclusion that she is in league with the watchers?

. By stage tradition his inconsequent:

Where's your father?

is prompted by a movement of the arras or an actual glimpse of

Polonius, or the King, or both. .

Her clumsy, fearful lie . . . shatters her credit with him. It is the

second such wound. The first ranked his mother as an adulteress;

and the poison of it infected all womankind for him.

This explanation is, like that of Dover Wilson, theatrically too frail. We

are asked to believe that an author who spent his working life in the thea-

ter hinges a crucial scene on a stage direction of which no mention is made

anywhere in the play. That Shakespeare intended for Hamlet to see or hear

the eavesdroppers is, as Arthur Colby Sprague remarks, “scarcely demon-

strable” (p. 152). And it would be contrary to Shakespeare’s habit of em-

ploying “built-in” stage directions, For example, when we are told “Look

Hamlet's Cue For Passion 101

where sadly the poor wretch comes reading,” we are to do so then and

not, as Dover Wilson would have us, before that point, when looking at

Hamlet would divert our attention from the important conversation of

Claudius, Gertrude, and Polonius. Our attention would be divided be-

tween Hamlet's overhearing (which in this interpretation is crucial) and

what he overhears (which is crucial for our following the plot of the play),

and there would be a risk of our missing one or both. Very clumsy stage

business for so practiced a hand. Gertrude’s line signaling Hamlet's ap-

pearance, along, with Polonius’ following line, covers Hamlet's long en-

trance and directs audience attention to him. Had our attention been pre-

viously with him, it would not need such direction

‘The Granville-Barker theory, though it might work for modern audi-

ences in making the change of mood in the nunnery scene comprehensible,

is too subtle for use on the large Elizabethan stage. Could the audience's

attention, concentrated on Hamlet and Ophelia, be distracted at all from

them, and if so, could it be distracted with dramatic justification? If an

inner stage existed, sight lines to it would almost certainly have been im-

perfect from many points of the theatre. We have no indication that any

scene of major consequence in Shakespeare, or any scene detailed and

minute, occurred on the inner stage. Could we assume such an important

piece of business as the accidental appearance of the spies—necessarily vis-

ible to us as to the character—to have done so? Or we could assume that

the eavesdroppers are further downstage, behind a screen. To keep them

so much in our consciousness by placing them near us again distracts our

attention from Hamlet and Ophelia and endangers their whole scene, The

fact is that interest in this scene is concentrated solely on Hamlet and

Ophelia, not on Claudius and Polonius. And thus the latter pair must have

gone offstage and remained there—behind the arras, or elsewhere out of

sight—to avoid dividing our attention by making us conscious of their

presence. As Dover Wilson points out, making them suddenly visible is a

clumsy mechanism suggesting incompetence on the part of the spies. Mar-

tin Holmes, a practicing director, has this to say of such a device:

The watchers have to betray themselves by a device that the audi-

ence can see quite plainly, since Hamlet says nothing to draw their

attention to it, and the result is likely to be a ponderous and

clumsy movement that instinctively lowers our opinion of the

King’s intelligence—and, subconsciously, of the dramatist’s.

Whether it is a matter of feet under a curtain or shadows on a wall,

102 Artur Nort Kincarp

the fact that Hamlet and the audience can all see it gives it an air of

ludicrous inefficiency, and in an instant the eavesdroppers are no

longer sinister but only rather absurd. . . .*

We have a similar situation later on when Polonius is secreted behind

the arras in the closet scene (III.iv). We are allowed to forget his presence,

so that we are not diverted from Hamlet and his mother, until the moment

when Polonius calls attention to his presence by actually crying out—not

by sticking out a clumsy head or foot. Shakespeare deviates from his

sources to introduce this action and does so almost certainly because his

stage demanded so clear a signal to attract the audience's attention. This is

a deliberate action, for it heralds Polonius’ death, which furthers the plot.

Once he is slain, identified, and given a perfunctory elegy, his body is for-

gotten, presumably remaining behind the arras, so that the Gertrude-

Hamlet scene may be played out without distraction until the point where

it becomes important to show Hamlet's response to his deed and to get

Hamlet and the body off the stage.

In conclusion to this argument, we cannot, I think, allow the motive for

Hamlet's behavior in the nunnery scene to hinge on something so theatri-

cally tenuous as a false entrance or an accidental view of the eavesdroppers,

either of which could easily be missed by half the audience in any type of

theatre, neither of which is reinforced by any mention in the play itself,

and both of which divide our attention in a clumsy fashion.

Dover Wilson and Granville-Barker agree on one point. Dover Wilson

calls Ophelia’s reply to the query Where's your father?” “the crowning

point of her treachery, that provokes the frenzy with which the episode

closes” (p. 134). Granville-Barker wishes us to assume that Ophelia’s

“clumsy, fearful lie” (p. 79) sets Hamlet's fury in motion. Again we have no

evidence. Nothing in Ophelia’s reply or in Hamlet's reaction to it indicates

that she has been clumsy or fearful or that Hamlet believes her to be lying.

In fact, his response and his subsequent behaviour prove just the opposite:

that he believes her to be telling the truth.

A far more plausible explanation for Hamlet's violent change of attitude

at this point in the scene and his actions throughout the remainder of it

can be found in the contemporary expectations of a young gentlewoman’s

behavior. These can be traced in others of Shakespeare's plays and in the

courtesy literature of the period. With remarkably few exceptions do

Shakespeare’s women of good repute appear unaccompanied except in

their own homes and at church. They are given more liberty by the author

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Post ColonialismDocument73 paginiPost ColonialismDanika Barker100% (3)

- Curriculum Implementation PlanDocument7 paginiCurriculum Implementation PlanDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Archetypal Literary CriticismDocument7 paginiArchetypal Literary CriticismDanika Barker100% (10)

- Formalist Literary CriticismDocument8 paginiFormalist Literary CriticismDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1 Formative Project RubricDocument3 paginiUnit 1 Formative Project RubricDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Citizen Journalism LessonDocument10 paginiCitizen Journalism LessonDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENG4C Assessment Plan With LinksDocument3 paginiENG4C Assessment Plan With LinksDanika Barker100% (1)

- This I Believe Essays 1Document5 paginiThis I Believe Essays 1Danika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elearning Vision StatementDocument6 paginiElearning Vision StatementDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reimagining HamletDocument2 paginiReimagining HamletDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Network Sites and Their Applications To Secondary ClassroomsDocument9 paginiSocial Network Sites and Their Applications To Secondary ClassroomsDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Danika Barker - Synthesis and AnalysisDocument11 paginiDanika Barker - Synthesis and AnalysisDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Elgin Collegiate InstituteDocument5 paginiCentral Elgin Collegiate InstituteDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- This I Believe OutlineDocument2 paginiThis I Believe OutlineDanika Barker100% (1)

- This I Believe RubricDocument2 paginiThis I Believe RubricDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Believe in YourselfDocument2 paginiBelieve in YourselfDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

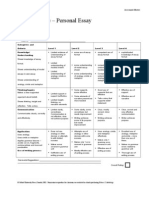

- Personal Essay Outline TemplateDocument2 paginiPersonal Essay Outline TemplateDanika Barker100% (1)

- The Personal Narrative EssayDocument1 paginăThe Personal Narrative EssayDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dignity of Work by Charles FinnDocument2 paginiThe Dignity of Work by Charles FinnDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- This I Believe Essays 1Document5 paginiThis I Believe Essays 1Danika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hamlet Project RubricDocument2 paginiHamlet Project RubricDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparing Poems On Similar ThemesDocument1 paginăComparing Poems On Similar ThemesDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENG4U Assessment Plan 2013-2014Document2 paginiENG4U Assessment Plan 2013-2014Danika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing PromptsDocument2 paginiWriting PromptsDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENG4C Writing Diagnostic Scoring ScaleDocument1 paginăENG4C Writing Diagnostic Scoring ScaleDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hamlet Multi Genre ProjectDocument4 paginiHamlet Multi Genre ProjectDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Explication of PhotographDocument2 paginiSample Explication of PhotographDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1key Ideas in Hamlet 1) Nemesis: Comes From The AristotelianDocument1 pagină1key Ideas in Hamlet 1) Nemesis: Comes From The AristotelianDanika BarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)