Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

1 - Sex Determination

Încărcat de

mis_administratorDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

1 - Sex Determination

Încărcat de

mis_administratorDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

SEX DETERMINATION

Sex Determination

Jennifer S. Florida, Ph.D. and David Stockwell

Sexual Reproduction is the masterpiece of nature. (Erasmus Darwin, 1791)

Abstract This paper is an overview of scientific literature regarding the aspects of gender determination. The varying methods of sex determination are presented as a cross-section of the factors involved. This article discussed sex determination by presenting the information in four distinct parts. The first section tackled the non-genetic and genetic sex determination system. The second section outlined the different disorder of sexual development. The third section enumerated the methods of pre-natal sex determination while the next section identified the different methods of sex selection. The conclusion deals with consequences a changing environment or knowledge of a childs gender as it may affect the gender ratio and ultimately the species.

Keywords:

chromosome theory, gender anomalies, genetics, methods of gender determination, sex selection

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

Introduction One of the oldest and most significant questions in embryology is the mechanism by which an individuals sex is determined. According to Aristotle, sex is determined by the heat and passion of the male during intercourse. If the male's heat could overwhelm the female's coldness, then a male child would form. In contrast, if the female's coldness was too strong (or the male's heat too weak), a female child would form (Hake & O'Connor, 2008). The more heated the passion, the greater the probability of male offspring. In 1890, Geddes and Thomson (as cited in Law, 2005) concluded, Constitution, age, nutrition, and environment of the parents determine the sex. Factors favoring the utilization of energy and nutrients influenced one to have male offspring. Correns (1900), based on Mendels work, speculated that the 1:1 sex ratio of most species could be achieved if the male was heterozygous and the female was homozygous as regarding the sex-determining factor. In 1905, Stevens and Wilsons established the correlation of female sex with XX sex chromosomes and male sex with XY or XO chromosomes (Carlson, 1996). A sex-determination system is a biological system that determines the development of sexual characteristics in an organism. In many cases, sex determination is genetic: males and females have different alleles (which are paired genes) or even different genes altogether that specify their sexual morphology. In animals, this is often accompanied by chromosomal differences. In other cases, sex is determined by environmental variables (such as temperature) or social variables (the size of an organism relative to other members of its population) or even the amount of nutrition available. Even though it has received much attention and research, the details of some sex-determination systems are not yet fully understood. Within Genetics, and in the most basic terms, a male is XY and a female is XX; however, Biblically, both man and woman were created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27.) So, whereas, science is focused on quantifiable distinctions such as sex-linked traits, hormones, and physiology, scripture acknowledges the equal involvement of an omnipotent force in both genders.

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

Discussion Non-genetic sex-determination system. Environmental sex determination. Temperature-dependent sex determination in turtles. With the exception of the genera Platemys (XY, Chelidae), Staurotypus (XY, Kinosternidae), and Siebenrockiella (XY) and Kachuga smithii (ZW) (Bataguridae), turtles lack heteromorphic (different) sex chromosomes (either XY male heterogamety, or ZW female heterogamety); their mechanism for sex determination is different than that in humans. Of the other turtles, only a few do not experience temperature (environmental) dependent sex determination (TSD). The incubation temperature of their eggs at the critical period of development, which is in the middle trimester, triggers the gonadal development leading to the sex of each hatchling. Two TSD patterns have been discovered in turtles. Pattern I, found in some Bataguridae, and the Carettochelyidae, Cheloniidae, Dermochelyidae, Emydidae, and Testudinidae, has a single transition zone of temperature below which incubation yields nearly or totally 100% males and above which only females are produced. Pattern II, known from the Pelomedusidae, Kinosternidae, Macroclemys temminckii (Chelydridae), and a few Bataguridae have two transition zones, with the development of males predominating at intermediate temperatures and females at both extremes; in most turtle species no constant incubation temperature within the transition zone yields 100% males (however, as exceptions, encountered so far, constant temperatures do yield 100% males in some Sternotherus and in Chelydra). Pattern I occurs chiefly in turtles in which the adult females are larger than adult males; Pattern II is found mainly in turtles in which females are smaller than males or in which body size is not dimorphic (different). In general, the smaller of the sexes is typically produced at the coolest possible incubation temperatures. Incubation temperature seems to have no great or little influence on sex ratios in turtles of the family Chelidae. Generally, eggs incubated at the lower range of the viable temperature range (22-27 Co) produce one sex, whereas eggs

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

incubated at higher range of the viable temperature (30 Co and above) produce the other. If eggs are incubated below 28 Co, all the turtles hatching from them will be male. Above 32 Co every egg will give rise to a female. Ferguson and Joanen (1982) concluded that sex is determined between 7-21 days of incubation (Bull & Voqt, 1979). Temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles. In reptiles, the temperature of the environment surrounding the eggs during a certain period of development is the deciding factor (Bull, 1980) and small changes of temperature can cause dramatic changes in the sex ratio. Eggs incubated at 30 Co or below produce all female alligators, whereas those incubated at 34 Co or above produce all males. Moreover, the nests constructed on and with fermenting leaves maintain a temperature of around (34 Co) give rise to males whereas those built in wet marshes, which have a temperature around (30 Co) produce females. Thus, the sex of many turtle and alligator species is based on the temperature of the eggs ambient environment (Crews et al., 1994). Location-dependent sex determination in Bonellia viridis and Crepidula fornicate. The sex of the echiuroid worm Bonellia depends upon where a larva settles. If the larva settles on a rocky surface it becomes female but if it settles on the proboscis (nose) of a female it becomes a parasitic male. Spending the rest of its life within the body of the female, it receives all its nutrients from its host while constantly fertilizing eggs (Baltzer, 1914; Leutert, 1974, as cited in Gilbert, 2000). In the slipper shell Crepidula fornicata, sex is determined by the organisms location in a mound of shells. If the snail is attached to a female it will become male. If, however, there is an abundance of males in a mound, this factor will cause a percentage of males to become females. However, once an organism becomes female, it can never revert back to the male gender (Coe, 1936). External factors. In some arthropods, sex is determined/controlled by infection. Bacteria of the genus Wolbachia alter the arthropods (spiders, insects, and crabs) sexuality. Since the bacteria live in the hosts

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

reproductive system and spread through eggs, sperm-producing males are actively selected against if not completely eliminated (Knight, 2001). Some species of wasps consist entirely of ZZ individuals, with sex determined by the presence of a specific strain of Wolbachia. Within the nematodes (small worms) that cause elephantiasis, the bacteria and the host are so intertwined that the destruction of the Wolbachia bacteria eliminates the colony (Knight, 2001). Parthenogenesis. Some species have no sex-determination system. Earthworms and some snails are true hermaphrodites and are capable of fertilizing each other and producing offspring. A few species of lizard, fish, and insect are all female and reproduce by parthenogenesis. Parthenogenesis, which literally means virgin birth, is a form of asexual reproduction in which the female produces offspring without the involvement of a male. In the checkered whiptail lizard (Aspidoscelis tesselata) females double the chromosomes within their gametes and never pair homologous chromosomes to ensure their offspring maintain a great amount of genetic diversity (Harmon, 2010). In (Megoura viviae) a species of aphid parthenogenesis and sexual reproduction are both practiced. In summer, the females XX reproduce asexually, with viable eggs already in the offspring at birth. This is known as telescoping. However in winter, the females randomly produce offspring that are XO this is achieved by dropping an X chromosome. This leads to a fertile male. When this male produces sperm only the X containing sperm are fully viable, ensuring that all offspring emerging from fertilized eggs in spring are XX females (Wilson, Sunnucks & Hales, 1997). Genetic sex-determination system. The chromosome theory of inheritance and sex linkage. According to Sutton and Boveris chromosome theory of inheritance proposed in 1902, genes are located on chromosomes (Mader, 2007). Just previous to this (end of 19th century) biologists had discovered that half of all sperm cells carry a structure called an X body. In 1905 the X bodies were determined

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

to be chromosomes - X chromosomes. Following that the Y, the smaller of the two chromosomes, was discovered in 1905. Together the X and Y chromosomes are known as the sex chromosomes. In 1949, Barr and Bertram found a chromatin mass in the nuclei of cells of females. This chromatin mass is called a Barr body. In 1961, Lyon postulated that the sex chromatin mass initiates the inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes. The activity of only one X chromosome is required or permissible for normal development in either male or female. Additional X chromosomal activity is effectively eliminated by condensation of the extra X chromosome. Sex chromatin represents the morphological expression of a genetic control mechanism. The Y chromosome directs the differentiation of the indifferent gonad in the testis. It is localized in/on the SRY (sex determining region of the Y chromosome) gene which is located in the testisdetermining region of Y chromosome. Systems of sex chromosomes. 1) XX-XO system (Protenor mode) (a) FemaleXX (b) MaleX (c) Occurs in some insects e.g. aphids 2) XX-XY System (Lygaeus mode) (a) FemaleXX (homogametic sex) (b) Male XY (heterogametic sex) (c) Occurs in Drosophila, mammals and some plants 3) ZZ-ZW System (a) FemaleXY (heterogametic sex) (b) MaleXX (homogametic sex) (c) Occurs in birds, butterflies and some fishes 4) X-Y-XY System (a) Occurs in organisms with alteration of generations (e.g., liverworts and vascular plants) (b) Male gametophytesY (c) Female gametophytesX (d) SporophytesXY

(Source: Carlson, B., 1996)

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

Mammals. The most familiar sex-determination system is the XY sex-determination system found in human beings and most other mammals. Sex determination is strictly chromosomal. The Y chromosome of the paternal male is the crucial inherited factor determining sex. The course of normal mammalian development is that of the female. That is, the development of mammals is in the female direction unless acted upon by genes within the Y chromosome. The egg gamete mother cell is said to be homogametic, because all of its cells possess the XX sex chromosomes. Sperm gametes are deemed heterogametic because around half of them contain the X chromosome while the others possess the Y chromosome. Based in this condition, there are two possibilities that can occur during fertilization through the interaction of male and female gametes, XX and XY. Since sperm are the variable factor (i.e. which sperm fertilizes the egg) they are responsible for determining the sex of the offspring. Chromosomes X and Y do not truly make up a homologous pair. They act similarly in their roles, but they are not homologous (the same). The X chromosome in humans is much longer than the Y chromosome, due to the fact that it contains more genes. These genes are said to be sex linked, since they are present in one of the sex chromosomes and not the other. During fertilization, when the opposing homologous chromosomes combine, the smaller Y chromosome offers no dominance against the 'extra' X chromosomes (Gilbert, 2000). Humans. In humans, the paternal male determines (the) sex of the offspring. A sperm cell contains either an X or a Y chromosome but an egg cell contains only an X chromosome. At the time of conception, the 23 chromosomes from the egg combine with the 23 chromosomes from the sperm to produce a zygote, or fertilized egg cell, which then contains 46 chromosomes. The offspring always inherits an X chromosome from the mother. If the father also contributes an X chromosome, the offspring will be female or XX. If the father donates a Y chromosome, then the offspring is male or XY.

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

Human sex determination is a genetic process that basically depends upon the presence of the Y chromosome in the fertilized egg. This chromosome stimulates a change in the undifferentiated gonad into that of the male (testicles). The gonadal action of the Y chromosome is controlled by a gene located near the centromere; (or center of the chromosome.) This gene codes for the production of a cell surface molecule called the H-Y antigen. Further development of the anatomic structures, both internal and external, associated with maleness is controlled through hormones produced by the testicles. The sex of an individual can be described in three different aspects: chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, and anatomic sex. Discrepancies among these, especially the latter two, result in the development of individuals with an ambiguous sex or gender, often called hermaphrodites. The phenomenon of homosexuality is of uncertain cause and is unrelated to research focused directly on sex-determining factors. It is of interest that in the absence of male gonads (testicles) the internal and external sex anatomy is always female, even if there is an absence of female ovaries. A female without ovaries will, of course, be infertile and will not experience any of the female developmental changes normally associated with puberty. Such a female will often demonstrate Turner's syndrome. If X-containing and Y-containing sperm are produced in equal numbers, with no other factors to consider, then according to simple chance one would expect the sex ratio at conception (fertilization) to be 50% boys and 50% girls, or 1:1. Direct observation of sex ratios among newly fertilized human eggs is not yet feasible, and sex-ratio data are usually collected at the time of birth. In almost all human populations of newborns there are a higher percentage of males; about 106 boys are born for each 100 girls. Throughout life, however, there is a slightly higher mortality rate among males; this slowly alters the sex ratio until, at a point slightly beyond the age of 50 years, there is a higher percentage of females. Studies indicate that male embryos suffer a relatively higher degree of prenatal mortality, so that the sex ratio at conception might be expected to favor Y chromosome sperm even more than the 106: 100 ratio observed at birth would suggest. Firm explanations for the apparent excess (above 50 %) of male conceptions have not been established; it is possible that Y-containing sperm have a higher survival rate within the female reproductive tract, or that they may be a little more successful in

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

reaching the egg first, in order to fertilize it. In any case, the sex differences are small, the statistical expectation for a boy (or girl) as regarding any single birth still being close to one out of two (Schafer & Goodfellow, 1996). Birds. Unlike mammals in which the male is heterozygous (XY) and the female is homozygous (XX), in birds, the sexdetermining-genes are reversed. Males are homozygous (ZZ) and females are heterozygous (ZW). This also indicates that the female determines the sex of the offspring (Mittwoch, 1971). Drosophila (Fruit Fly). The mechanism by which mammals and insect use the XX/XY system of sex determination is different. In Drosophila, sex is determined by the ratio of the number of X chromosomes to the number of autosomal sets. Sex determination is achieved by a balance of female determinants on the X chromosome and male determinants on the autosome (nonsex chromosome). If there is one X chromosome in a diploid (1X:2A), it is male. If there are two X chromosomes in a diploid cell (2X:2A), it is female. Thus all XO Drosophila are sterile males (Gilbert, 2000). Gender anomalies. Hermaphroditism. Hermaphrodites (from the Greek Hermes-Mercury and Aphrodite-Venus) are organisms in which both testis and ovary exist simultaneously. This condition is characteristic of many invertebrate classes, especially worms wherein the organism can mutually fertilize each other. This strategy aids in the survival of numerous species. In vertebrate, true hermaphroditism is less common and in birds and mammals, it is a pathological condition causing infertility. The most common vertebrate hermaphrodite are fishes. It is divided into 3 groups: (1) Synchronous hermaphrodite - ovaries and testicular tissues exist at the same time in which both sperm and eggs are produced; (2) Protogynous (female first) hermaphrodite the fish begins its life as a female but later become male (genetically sex changed); and(3) Protandrous (male first) hermaphrodite - the fish begins its life as a male but later become female (Carlson, 1996).

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

10

True hermaphroditism. An unusual cause of ambiguous genitalia is true hermaphroditism; in this syndrome, both ovarian and testicular tissue is present either in the same or in a contralateral gonad. Kim et al., (2002) identify true hermaphroditism (TH) as individuals who have both unequivocal ovarian tissue and testicular elements regardless of their karyotypes Pseudohermaphrodites. In pseudohermaphroditism, the person has the chromosomes of a man, but the external genitals are incompletely formed, ambiguous, or clearly female. Internally, testes may be normal, malformed, or absent. This condition is also called 46, XY with undervirilization. Forming normal male external genitals depends on the appropriate balance between male and female hormones; therefore, it requires the adequate production and function of male hormones. (A.D.A.M. Medical Dictionary, n.d.) To summarize, the following are some of the important characteristics of pseudohermaphoridtes: 1. Pseudohermaphrodites have either testicular or ovarian tissue, but not both 2. Generally the tissue is rudimentary 3. External genitalia are often ambiguous 4. Some are genetically female, but may look like males 5. Some are genetically male, but may look like females and lead traditional female sex lives but are infertile. Turners syndrome in humans (45, XO). 1. Due to nondisjunction in either male or female parent to produce gametes without an X chromosome 2. Incidence: 1/5000 female births 3. High proportion of spontaneous abortions is Turners and most Turners individuals are naturally aborted 4. Phenotypic features: short stature, webbed neckweb of skin between neck and shoulders, breast development absent or nearly so, some cognitive functions affected, but intelligence often about normal, pubic and axillary hair reduced or absent, infantile genitalia, usually sterile

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

11

Kleinfelters Syndrome (47, XXY). 1. Due to nondisjunction of X chromosome in male or female parent 2. Incidence: 1/1000 male births 3. Tends to be maternal age effect 4. Sometimes have more than two X chromosomes 5. Phenotypic features: long arms, breast development, little or no sperm production, small testes, usually mentally retarded XYY condition. 1. Due to nondisjunction of Y chromosome in male 2. Incidence: 1/1000 male births 3. Phenotypic features: above average height, fertile, higher frequency of retardation may have a statistical correlation with delinquency/criminal activity Poly-X Females (XXX, XXXX, XXXXX,). 1. Incidence: 1/1000 female births 2. Maternal age effect 3. Phenotypic features: possible infantile genitalia, possible underdeveloped breasts, fertile, a higher percentage of mental retardation, incidence increases with increasing number of X chromosomes

(Source: Carlson, 1996)

Methods of pre-natal sex determination. Amniocentesis. In the mother's womb, the fetus floats in amniotic fluid filled in the amniotic sac (bag of waters). A few cells of fetus are found in the fluid. The number of such cells increases as the fetus grows. However the amniotic sac gets increasingly filled up due to the growing size of fetus. Amniocentesis consists of inserting a long, aseptic needle into the amniotic sac through the mother's abdomen and withdrawing from it 15-20 cc of amniotic fluid for chromosomal analysis. It is usually performed between 16th to 18th weeks of pregnancy during which it is relatively easier to withdraw fluid containing sufficient number of cells without

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

12

damaging the placenta or fetus. It should preferably be carried out under the ultrasonic cover by means of which the movement of the fetus and location of placenta can directly be viewed on a screen using in audible sound waves. This helps in the insertion of needle without causing any damage to mother, fetus or placenta. (Atala, Lanza, Thompson & Nerem, 2008) Ultrasound. An ultrasound exam is a procedure that uses high-frequency sound waves to scan a woman's abdomen and pelvic cavity, creating a picture (sonogram) of the baby and placenta. The traditional ultrasound procedure involves placing gel on the womans abdomen to work as a conductor for the sound waves. A transducer is used to produce sound waves into the uterus. The sound waves bounce off bones and tissue returning back to the transducer to generate black and white images of the fetus. The external genitalia of fetus are not well defined even in 5th month of pregnancy. It is on weeks 10 to 12 of pregnancy where genitals appear well differentiated (Merz, 1997). Indigenous method. The traditions within the Philippines in determining the gender of a fetus are as numerous and various as the islands from which they come from. The shape and positioning of the mothers stomach are traditional indicators in determining whether it will be a boy or a girl. One of the more widespread beliefs is called malasma in which the puffy, swollen, or pimply face of the pregnant woman is the result of her unborn daughter is stealing her beauty. Even the mothers diet is considered as a portent of her unborn childs gender, if she has a craving for sweet food it will be a girl, but if she has a craving for fatty foods it will be a boy. In fact every step she takes during pregnancy is in itself an omen, if she leads with the left it will be a boy and if she leads with the right it will be a girl. Methods of sex selection. Sex selection is the attempt to control the sex of the offspring to achieve a desired sex. Sex pre selection technology is the more advanced stage of sex determination. Some of the methods are

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

13

based on actively rendering the second sex chromosome to be either a Y chromosome (resulting in a male), or an X chromosome resulting in a female. Shettles method. Shettles method developed by Landrum B. Shettles in the 1960s advocates intercourse two to four days prior to ovulation. The theory proposes that sperm containing the X (female) chromosome are more resilient than sperm containing the Y (male) chromosome. By the time ovulation occurs, the cervix should contain a higher concentration of female sperm still capable of fertilization (with most of the male sperm already dead). Intercourse close to ovulation, on the other hand, should increase the chances of conceiving a boy since the concentration of Y sperm is higher at the height of the menstrual cycle (Wicox, Weinberg, & Baird, 1995). Whelan method. Whelan method pioneered by Dr. Elizabeth Whelan, contradicts Dr. Shettles method. Whelan believes that the chances for conceiving a baby girl is much better when it is done as close to ovulation as possible. In this method, intercourse should be done 4-6 days before ovulation in order to have a baby boy, and 2-3 days before ovulation for a girl (Whelan, 1977). Ericsson method. Ericsson method developed and patented by Dr. Ronald J. Ericsson in 1970s uses higher concentrations of sperm of the desired sex to increase the likelihood of conceiving that gender. This technique aims to separate faster-swimming boy-producing sperm from slower-swimming girl-producing sperm by passing them through a column filled with human serum albumin (Ericsson, 1994). Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) or In vitro fertilization (IVF) technique. Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD). This was first developed in the 1980's. It is the application of genetic testing on a live embryo to determine the presence, absence or change in a

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

14

specific gene or chromosome prior to the placement of the embryo in the womb. It is done prior to the IVF technique. In Vitro Fertilization (IVF). After the eggs are recovered from the woman, they are fertilized with the fathers sperm and they start dividing. The resulting embryos at a certain stage of the development have a single cell removed and tested for sex chromosomes using the Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) technique. If the couple prefer baby boy, the embryos carrying both X and Y chromosomes, indicating male gender, are then transferred into the mothers uterus. Conclusion The discussions on the scientific aspects of gender determination as well as the distinction of an unborn childs gender, raised or openened the door, to many ethical and environmental concerns. Not all of the concerns are necessarily negative or complex. In the case of elphantitis, malaria, dengue, and river blindness scientists may better cure or even eliminate the disease through altering or killing the Wolbachia bacteria leading to the death of the vector (disease carrying) insect, as opposed to their current strategy of creating stronger and increasingly more dangerous antibiotics that are administered to the patient. However, as with any knowledge comes even greater responsibility. Even more so, with a sensitive subject that crosses over from empirical science to a societys or peoples moral and ethical sphere. Environmentally, the current theory of global climate change would indicate drastic consequences for species such as turtles and crocodiles, which have their gender characteristics determined by small changes in temperature. If the beaches where turtles lay their eggs experience a significant enough increase in temperature than it could lead to a disproportionate percentage of one gender over the other and to a population collapse if not extinction. As humans gain further information about sexuality, it becomes apparent how small biological changes or factors such as food availability and environmental quality can have drastic affects on the species as a whole. However, the greatest concern

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

15

would be with the human species itself. Knowledge of the fetuss gender in nations where one gender is preferred over the other has already led to sex-based abortions to a degree that has caused a significantly skewed ratio. Governments, in certain countries, have already banned doctors from informing expectant parents on the gender of their child in order to reduce sex-based abortions and population gender imbalance. A second issue arising from fetal genetic testing would occur when the parents are informed that the fetus has a genetic abnormality such as Turners or Klieinfelters syndrome. Knowing that the child is neither fully male nor fully female will lead to a difficult decision. As gender determination is researched more and understood within the animal kingdom, entirely new issues can quickly come to the forefront. For example, if bacteria, temperature, or the presence of certain chemicals during development affect the gender of animals then it is possible for scientists to recreate these conditions in humans to ensure one gender or trait above another. This paper is not to set forth to provide a single answer, persuade an audience, or simply add another chapter to an already lengthy and complicated encyclopedia of science. However, like all responsibly practiced science in the modern context, it is designed to educate both in factual or empirical knowledge while also reminding the reader of the delicate balance, possible degradation, as well as foreseeing possible consequences of the research itself. References A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Intersex. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001669.htm Atala, A., Lanza, R., Thompson, J. A., & NeremR. M. (2008). Principles of regenerative medicine. MA: Academic Press. New International Version. (1984). Caloocan City: Biblica Publishing.

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

16

Bull, J. J. (1980). Sex determination in reptiles. Biol. Rev., 55, 321. Bull, J. J. & Voqt, R.C. (1979). Temperature-dependent sex determination in turtles. Science, 206 (4423), 186-8. Carlson, B. (1996). Pattens foundation of embryology. New York: McGraw-Hill. Coe. W. R. (1936). Sexual phases in crepidula. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 72, 455477. Correns, C. (1900). G. Mendel's Law Concerning the Behavior of Progeny of Varietal Hybrids. (L. K. Piternick, Trans.). Appears in Genetics [1950], pp. 33-41, and Stern and Sherwood (1966), The Origin of Genetics: A Mendel Source Book pp. 119-132. Crews, D., Bergeron, J. M., Flores, D., Tousignant, A., Skipper, J. K. & Wibbels, T. (1994). Temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles: proximate mechanisms, ultimate outcomes, and practical applications. Developmental Genetics, 15(3), 297-312. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8062460 Ericsson, R. J. (1994). Sex selection: Sex selection via albumin columns: 20 years of results. Human Reproduction, 9(10), 1787-1788. Retrieved from http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/ content/9/10/1787.extract Ferguson, M. W. J., & Joanen, T. (1982). Temperature of egg incubation determines sex in Alligator mississippiensis. Nature, 296, 850-853. Gilbert, S. F. (2000). Developmental biology (6th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. Hake, L., & O'Connor, C. (2008). Genetic mechanisms of sex determination. Nature Education. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/GeneticMechanisms-of-Sex-Determination-314 Hans, E. (2001). Hens, cocks and avian sex determination: A quest for genes on Z or W? Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/v2/n3/full/embor459.ht ml

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

17

Harmon, K. (2010. Feb. 21). No sex needed: All-female lizard species cross their chromosomes to make babies. Scientific American, 32. Retrieved from

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=asexu al-lizards

Human genetics. (n.d.). Available from http://www.britannica.com/ EBchecked/topic/228983/human-genetics Knight, J. (2001). Meet the herod bug. Nature, 412, 12-14. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v412/ n6842/full/412012a0.html Law, A. (2005). The ghost of Patrick Geddes: Civics as applied sociology. Sociological Research Online, 10(2). Mader, S. S. (2007). Biology (9th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw Hill Higher Education. Merz, E. (1997). Ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology (2nd ed.). Germany: Grammlich Pliezhausen. Mittwoch, U. (1971). Sex determination in birds and mammals. Nature, 231(5303), 432-4. Schafer, A. J., & Goodfellow, P. N. (1996). Sex determination in humans. 18(12), 955-63. Sex determination and sex chromosomes. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.biol.andrews.edu/gen/l7.htm Sex-determination system. (24 July 2004.). Retrieved from http://july.fixedreference.org/en/20040724/wikipedia/Sexdetermination_system Slack, J. M. W. (2001). Essential developmental biology. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell. Whelan, E. (1977). Boy or girl. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. Wicox, A. J., Weinberg, C. R., & Baird, D. D. (1995). Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation: Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. The New England Journal of Medicine, 333, (23), 1517-1521. Retrieved from http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele= afficheN&cpsidt=2919378

LCCM Review

SEX DETERMINATION

18

Wilson, A. C., Sunnucks, P., & Hales, D. F. (1997). Random loss of X chromosome at male determination in an aphid, sitobion near fragariae, detected using an x-lined polymorphic microsatellite marker. Genetic. Research, 69, 233-236. Retrieved from http://www.biolsci.monash.edu.au/staff/ sunnucks/docs/GeneticalRes/RandomInheritance.pdf

LCCM Review

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Developmental Biology, 12th Edition (Michael J.F. Barresi, Scott F. Gilbert)Document48 paginiDevelopmental Biology, 12th Edition (Michael J.F. Barresi, Scott F. Gilbert)Nita DelinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chromosomal sex determination systems overviewDocument61 paginiChromosomal sex determination systems overviewDeepak maliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Inheritance and Variation-NotesDocument7 paginiPrinciples of Inheritance and Variation-NotesVaibhav ChauhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sex Determination in MammalsDocument33 paginiSex Determination in MammalsBinita SedhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Inheritance and Variations: By: Dr. Anand ManiDocument113 paginiPrinciples of Inheritance and Variations: By: Dr. Anand ManiIndu YadavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sex Determination in DrosophilaDocument19 paginiSex Determination in DrosophilaSheerin Sulthana100% (2)

- Lecture 1B - Benzer's Work and Complementation TestDocument5 paginiLecture 1B - Benzer's Work and Complementation TestLAKSHAY VIRMANI100% (1)

- 06 GastrulationtxtDocument38 pagini06 GastrulationtxtHafidzul HalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Male Sterility 29-3-17Document64 pagini5 Male Sterility 29-3-17Aizaz AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polytene and Lampbrush ChromosomesDocument3 paginiPolytene and Lampbrush Chromosomesneeru.bhagatÎncă nu există evaluări

- BioSci 101 Test 2 NotesDocument12 paginiBioSci 101 Test 2 NotesPianomanSuperman100% (1)

- ChromosomesDocument4 paginiChromosomesعامر جدونÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bio 244 Chapter 10 NotesDocument7 paginiBio 244 Chapter 10 NotesEscabarte Abkilan Cyrian GrioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mitosis vs Meiosis ComparisonDocument1 paginăMitosis vs Meiosis ComparisonLaura Cormane100% (1)

- Stem CellsDocument22 paginiStem Cellsanon_204342684Încă nu există evaluări

- 15 Sex DeterminationDocument40 pagini15 Sex Determinationapi-3800038Încă nu există evaluări

- Dynamics of The Mammalian Sperm Plasma Membrane in The Process of FertilizationDocument39 paginiDynamics of The Mammalian Sperm Plasma Membrane in The Process of FertilizationWachiel ArhamzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sex Determination PDFDocument15 paginiSex Determination PDFShalmali ChatterjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cloning Dolly & MicromanipulationDocument29 paginiCloning Dolly & Micromanipulationnitinyadav16Încă nu există evaluări

- Gametogenesis Process in HumanDocument13 paginiGametogenesis Process in HumanRiski UntariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gene Expression VarietiesDocument17 paginiGene Expression VarietiesadekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chromosomal Disorders SimpleDocument8 paginiChromosomal Disorders SimpleSadia KanwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 12 Biology Chapter 7 Revision NotesDocument20 paginiClass 12 Biology Chapter 7 Revision NotesMADIHA MARIAM KHANÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Introduction To Phylogenetic Analysis - Clemson UniversityDocument51 paginiAn Introduction To Phylogenetic Analysis - Clemson UniversityprasadburangeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategies in Enhancement in Food Production WorksheetDocument8 paginiStrategies in Enhancement in Food Production WorksheetRajuGoud BiologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Staar Eoc 2016test Bio F 7Document39 paginiStaar Eoc 2016test Bio F 7api-293216402Încă nu există evaluări

- Cytoplasmic InheritanceDocument13 paginiCytoplasmic InheritanceIzza NafisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture Outline: Chapter 5 The Structure and Function of MacromoleculesDocument12 paginiLecture Outline: Chapter 5 The Structure and Function of MacromoleculesSanvir RulezzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calvin Cycle (Dark Reactions / Light Independent Reaction)Document47 paginiCalvin Cycle (Dark Reactions / Light Independent Reaction)L'ya Lieslotte100% (2)

- Infertility and Candidate Gene Markers For Fertility in Stallions A ReviewDocument7 paginiInfertility and Candidate Gene Markers For Fertility in Stallions A ReviewBenjamínCamposÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 3 AnswersDocument3 paginiQuiz 3 AnswersEdilberto PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cell Cycle Cell Division PDFDocument13 paginiCell Cycle Cell Division PDFmuzamil shabir100% (1)

- Karyotyping: A Test to Examine ChromosomesDocument16 paginiKaryotyping: A Test to Examine ChromosomesIan MaunesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Genetic PrinciplesDocument37 paginiBasic Genetic PrinciplesShaira Reyes0% (1)

- 12 Biology - Principles of Inheritance and Variations - Notes (Part I)Document13 pagini12 Biology - Principles of Inheritance and Variations - Notes (Part I)Jayadevi ShanmugamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Embryonic Fate MapDocument25 paginiEmbryonic Fate MapImran MohsinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mendelian Laws & Patterns of Inheritance LabDocument24 paginiMendelian Laws & Patterns of Inheritance LabNau MaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter-7 Evolution: Welcome StudentsDocument104 paginiChapter-7 Evolution: Welcome StudentsMANAV raichandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gene Mapping: Biology 20Document5 paginiGene Mapping: Biology 20Soham SenguptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rat Urinary and Reproductive SystemDocument4 paginiRat Urinary and Reproductive SystemAnkit NariyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drosophila Lab ReportDocument4 paginiDrosophila Lab ReportAnthony100% (1)

- Biology Cls 12 ProjectDocument13 paginiBiology Cls 12 ProjectARITRA KUNDUÎncă nu există evaluări

- Molecular Basis of InheritanceDocument7 paginiMolecular Basis of InheritancePralex PrajapatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chlorophyceae: VolvoxDocument13 paginiChlorophyceae: VolvoxAnilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spermatids: Seminiferous TubulesDocument4 paginiSpermatids: Seminiferous TubulesMarie Patrice LehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes: - Reproduction in Organisms, For Class 12Document18 paginiNotes: - Reproduction in Organisms, For Class 12Subho BhattacharyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drosophila MelanogasterDocument13 paginiDrosophila MelanogasterDavid MorganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Karyotype Analysis in Zea Mays L. Var. Everta (Popcorn) Cultivated Within Owerri, Southeast NigeriaDocument6 paginiKaryotype Analysis in Zea Mays L. Var. Everta (Popcorn) Cultivated Within Owerri, Southeast NigeriaImpact JournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Cycle of OedogoniumDocument16 paginiLife Cycle of OedogoniumMuskan Sachdeva 0047Încă nu există evaluări

- SpermatogenesisDocument13 paginiSpermatogenesiszuha khanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Golgi Apparatus MypptDocument16 paginiGolgi Apparatus MypptPrabhavati GhotgalkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Species Concepts ExplainedDocument26 paginiSpecies Concepts ExplainedmashedtomatoezedÎncă nu există evaluări

- TOrsionDocument19 paginiTOrsionDrSneha VermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Welcome All !... : Presented By: Dr. Nidhi SrivastavaDocument55 paginiWelcome All !... : Presented By: Dr. Nidhi SrivastavaNivedita DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- EcosystemDocument8 paginiEcosystemHarsha HinklesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parasites & People - Host Parasite Relationship - RumalaDocument40 paginiParasites & People - Host Parasite Relationship - RumalamicroperadeniyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Juyena Et Al-2012-Journal of AndrologyDocument16 paginiJuyena Et Al-2012-Journal of AndrologyAnamaria Blaga PetreanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Non DisjunctionDocument15 paginiNon DisjunctionKhan SadiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Plasma Proteins V5: Structure, Function, and Genetic ControlDe la EverandThe Plasma Proteins V5: Structure, Function, and Genetic ControlFrank PutnamEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- 5-Image in CreativityDocument12 pagini5-Image in Creativitymis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7-Deconstructing Life (In Art and Science)Document5 pagini7-Deconstructing Life (In Art and Science)mis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8-GMA On The National StageDocument16 pagini8-GMA On The National Stagemis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6-Is Faith CommunicableDocument6 pagini6-Is Faith Communicablemis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2-Teacher Training The X FactorDocument6 pagini2-Teacher Training The X Factormis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3-Value Added Tax Its Impact in The Philippine EconomyDocument23 pagini3-Value Added Tax Its Impact in The Philippine Economymis_administrator100% (8)

- 4-Sketching Philippine LaborDocument18 pagini4-Sketching Philippine Labormis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-Notes On The Pedagogy of St. Augustine and The Foundations of Augustine's SpiritualityDocument15 pagini1-Notes On The Pedagogy of St. Augustine and The Foundations of Augustine's Spiritualitymis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolution of PEDocument14 paginiEvolution of PEmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Students' Satisfaction RatingDocument11 paginiStudents' Satisfaction Ratingmis_administrator100% (3)

- 4 Designing InstructionDocument22 pagini4 Designing Instructionmis_administrator100% (1)

- 1-Assessment of Customer Satisfaction On La Residencia 1 and La Residencia 2Document10 pagini1-Assessment of Customer Satisfaction On La Residencia 1 and La Residencia 2mis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artificial SweetenersDocument5 paginiArtificial Sweetenersmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5-Ibsen Meets ChekhovDocument9 pagini5-Ibsen Meets Chekhovmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Action ResearchDocument14 pagini3 Action Researchmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beyond Predestination and Free WillDocument9 paginiBeyond Predestination and Free Willmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of The BibleDocument1 paginăThe Role of The Biblemis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reinventing Education Through E-LearningDocument1 paginăReinventing Education Through E-Learningmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Continuing JourneyDocument6 paginiContinuing Journeymis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 - LCCM Solar Cooling SystemDocument12 pagini6 - LCCM Solar Cooling Systemmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Causes of Failure and Under AchievementDocument1 paginăCauses of Failure and Under Achievementmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4-Online CounselingDocument11 pagini4-Online Counselingmis_administrator100% (1)

- 3-Critical Thinking & NursingDocument13 pagini3-Critical Thinking & Nursingmis_administrator100% (4)

- 100 Days of PNoyDocument45 pagini100 Days of PNoymis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5-Teaching & ResearchDocument17 pagini5-Teaching & Researchmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2-Challenges in Indie FilmDocument10 pagini2-Challenges in Indie Filmmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Computer-Simulated Endocrine PhysiologyDocument1 paginăComputer-Simulated Endocrine Physiologymis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greening PantabanganDocument1 paginăGreening Pantabanganmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Right CupDocument1 paginăThe Right Cupmis_administratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06 Cause and Effect PDFDocument17 pagini06 Cause and Effect PDFnewdragonvip06Încă nu există evaluări

- Bug GuideDocument25 paginiBug GuideHasbi AshshidiqqiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Differences Between in Vitro and in VivoDocument3 paginiDifferences Between in Vitro and in VivoMuhammad N. HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

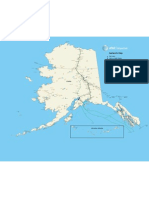

- AT&T Alascom NetworkDocument1 paginăAT&T Alascom NetworkrbskoveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science 8: Learning Activity SheetDocument9 paginiScience 8: Learning Activity SheetVan Amiel CovitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gujarati StoryDocument3 paginiGujarati StoryTanveerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hair in Toxicology - An Important Bio-MonitorDocument376 paginiHair in Toxicology - An Important Bio-Monitoradriancovaci1972Încă nu există evaluări

- Crochet Now March 2019Document128 paginiCrochet Now March 2019Chris Chrys100% (23)

- Gender of NounsDocument4 paginiGender of NounsAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BUsiness MalpracticesDocument5 paginiBUsiness MalpracticesAishwaryaSushantÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samuel Pepys' diary entries provide insight into 17th century lifeDocument9 paginiSamuel Pepys' diary entries provide insight into 17th century lifeMasyuri SebliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shang Han LunDocument3 paginiShang Han Lunwuweitao50% (2)

- Human anatomy & physiology sampler questionsDocument13 paginiHuman anatomy & physiology sampler questionsLauraLaine100% (3)

- Agricola RulebookDocument12 paginiAgricola RulebookAndrew WatsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 892902-Horror at Havels Cross PF v1 1Document4 pagini892902-Horror at Havels Cross PF v1 1vttownshendÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Glomerulonephritis Causes and DiagnosisDocument2 paginiAcute Glomerulonephritis Causes and DiagnosisLindsay MillsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Placenta Previa NCP 1Document6 paginiPlacenta Previa NCP 1Faye Nervanna Alecha Alferez83% (18)

- Monthly medical supply checklist for Ponek roomDocument4 paginiMonthly medical supply checklist for Ponek roomDewi FitrianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993)Document49 paginiChurch of Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal Essay Penilaian Akhir Semester Ganjil Tahun Pelajaran 2020/2021Document2 paginiSoal Essay Penilaian Akhir Semester Ganjil Tahun Pelajaran 2020/2021Lilik SuryawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- KG 2 English Scope and Sequence 2017-2018 2 1Document34 paginiKG 2 English Scope and Sequence 2017-2018 2 1api-294972271Încă nu există evaluări

- Midgard BasicsDocument2 paginiMidgard BasicsAnonymous xwoDOQÎncă nu există evaluări

- The DORN - Self Help ExerciseDocument11 paginiThe DORN - Self Help Exerciseyansol100% (1)

- The Dog Who Lost His Bark by Eoin Colfer & P. J. Lynch Chapter SamplerDocument15 paginiThe Dog Who Lost His Bark by Eoin Colfer & P. J. Lynch Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intensive Writing AssessmentDocument4 paginiIntensive Writing Assessmentapi-331504072Încă nu există evaluări

- Hematology CasesDocument27 paginiHematology Casessamkad214100% (2)

- Chapter 1 Lecture PowerPoint-1Document45 paginiChapter 1 Lecture PowerPoint-1hawa keiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Sentence Patterns in EnglishDocument18 paginiBasic Sentence Patterns in Englishysheng98Încă nu există evaluări

- Pengendalian Dan Pencegahan Tuberkulosis: Diah HandayaniDocument40 paginiPengendalian Dan Pencegahan Tuberkulosis: Diah HandayanirudyfirÎncă nu există evaluări

- My First Home: A Young Horse's MemoriesDocument34 paginiMy First Home: A Young Horse's MemoriesLearn EnglishÎncă nu există evaluări