Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Benedict - Patterns of Culture - The Individual and The Pattern of Culture

Încărcat de

Buddy Seed100%(3)100% au considerat acest document util (3 voturi)

4K vizualizări25 paginiThere is no proper antagonism between society and that of the individual. His culture provides the raw material of which the individual makes his life. The richest musical sensitivity can operate only within the equipment of its tradition. A talent for observation expends itself in some Melanesian tribe.

Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Benedict - Patterns of Culture__the Individual and the Pattern of Culture

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThere is no proper antagonism between society and that of the individual. His culture provides the raw material of which the individual makes his life. The richest musical sensitivity can operate only within the equipment of its tradition. A talent for observation expends itself in some Melanesian tribe.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

100%(3)100% au considerat acest document util (3 voturi)

4K vizualizări25 paginiBenedict - Patterns of Culture - The Individual and The Pattern of Culture

Încărcat de

Buddy SeedThere is no proper antagonism between society and that of the individual. His culture provides the raw material of which the individual makes his life. The richest musical sensitivity can operate only within the equipment of its tradition. A talent for observation expends itself in some Melanesian tribe.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 25

VIII

The Individual and the Pattern of Culture

THE large corporate behaviour we have discussed is

nevertheless the behaviour of individuals. It is the world

with which each person is severally presented, the world

from which he must make his individual life. Accounts of

any civilization condensed into a few dozen pages must

necessarily throw into relief the group standards and de-

scribe individual behaviour as it exemplifies the motiva-

tions of that culture. The exigencies of the situation are

misleading only when this necessity is read off as implying

that he is submerged in an overpowering ocean.

There is no proper antagonism between the r(He of

society and that of the individual . One of the most mis-

leading misconceptions due to this nineteenth-century

dualism was the idea that what was subtracted from

society was added to the individual and what was sub-

tracted from the individual was added to society. Philoso-

phies of freedom, political creeds of laissez [aire,

revolutions that have unseated dynasties, have been built

on this dualism. The quarrel in anthropological theory be-

tween the importance of the culture pattern and of the

individual is only a small ripple from this fundamental

conception of the nature of society.

In reality, society and the individual are not antagonists .

His culture provides the raw material of which the indi-

vidual makes his life. If it is meagre , the individual suffers;

if it is rich, the individual has the chance to rise to his

opportunity. Every private interest of every man and

woman is served by the enrichment of the traditional stores

of his civilization. The richest musical sensitivity can

operate only within the equipment and standards of its

tradition. It will add, perhaps importantly, to that tradi-

tion. but its achievement remains in proportion to the

instruments and musical theory which the culture has

provided. In the same fashion a talent for observation

expends itself in some Melanesian tribe upon the negligible

218

I

,

I

I

TIlE INDIVIDUAL AND THE PATTERN OP CULTURE 219

borders of the magico-religious field. For a realization

of its potentialities it is dependent upon the development

of scientific methodology, and it has no fruition unless

the culture has elaborated the necessary concepts and

tools.

Theman in the street .still.thinks in termsof a neeessaIY

antagonism between

measure this is because in our cfViI izatlon ihe regulative

activities of sociery are singled out, and we tend to iden-

tify society with the restrictions the law imposes upon us.

The law lays down the number of miles per hour that I

may drive an automobile . If it takes this restriction away,

I am by that much the freer . This basis for a fundamental

antagonism between society and the individual is naive

indeed when it is extended as a basic philosophical and

political notion. Society is only incidentally and in certain

situations regulative, and law is not equivalent to the

social order. In the simpler homogeneous cultures coUec-

tive habit or custom may quite supersede the necessity for

any development of formal legal authority. American

Indians sometimes say: 'In the old days, there were no

fights about hunting grounds or fishing territories. There

was no law then, so everybody did what was right.' The

phrasing makes it clear that in their old life they did not

think of themselves as submitting to a social control im-

posed upon them from without . Even in our civilization

the law is never more than a crude implement of society,

and one it is often enough necessary to check in its arr0-

gant career. It is never to be read off as if it were the

equivalent of the social order.

Society in its full sense as we have discussed it in this

volume is never an entity separable from the individuals

who compose it. No individual can arrive even at the

threshold of his potentialities without a culture in which

he participates . Conversely, no civilization has in it any

element which in the last analysis is not the contribution

of an individual. Where else could any trait come from

except from the behaviour of a man or a woman or a

child?

It is largely because of the traditional acceptance of a

con1lict between society and the individual , that emphasis

upon cultural behaviour is so often interpreted as a denial

220 PATTERN S OP CULTURE:

of the autonomy of the individual . Th e reading of Sum-

ner's Folkways usually rouses a protest at the limitations

such an interpr etati on pl aces upon the scope and initi ative

of the individu al. Anthropology is often believed to be a

counsel of despair which make s unten abl e a ben eficent

human illusion . But no anthropo logis t with a backgr ound

of experi ence of other cultures has ever believed that

individuals were automatons, mechanically carrying out

the decree s of their civilization. No culture yet observed

has been abl e to eradicate the differ ences in the temper a-

ments of the persons who co mpose it. It is always a give-

and-take. The pr obl em of the ind ividual is not clarified hy

stressing the -antagonism between culture and the indi-

vidual. but by stressing their mutual reinforcement. Thi s

rapport is so close that it is not possibl e 10 discu ss patt erns

of cultur e without considering specifically their rel ation to

individual psychology.

We have seen that any society selects some segment of

the arc of possible human behaviour, and in so far as it

achieves integration its institutions tend to further the

expressi on of its selected segment and to inhibit oppos ite

expressi ons. But these opposite expre ssions are the con-

genial responses, nevertheless, of a ce rtain proportion of

the carrier s of the culture . We have already di scussed

the reasons for believing that this selection is primarily

cultural and not biological. We cannot . ther efor e, even

on theor etical grounds imagine that all the congeni al

respon ses of all its people will be equa lly served by the

institution s of any culture . To under stand the beh aviour

of the individual. it is not merely necessary to relate his

person al life-hi story 10 his endow ments , and to measur e

these against an arbitrarily selected normality. It is neces-

sary also to rel at e his con geni al responses to the beh aviour

that is singled out in the institutions of his culture.

The vast proportion of all individuals who are born into

any soci ety always and whatever the idiosyncrasies of its

institutions. assume, as we have seen, the behaviour dic-

tated by that society. Th is fact is always int erpr et ed by

the carri ers of tha t cultur e as being due to the fact that

their particul ar institutions reflect an ultimate and uni-

versal sanity. The actual reason is quite different. Most

people are sha ped to the form of their cultur e becaus e of

I

i

I

I

1

THE AND THE PATTERN OF CULTURE 221

the enormous malleability of their original endowment.

They are plastic to the moulding force of the society into

which they are born . It does not matter whether, with

the Northwest Coast, it requires delusions of self-refer-

ence, or with our own civilization the amassing of posses-

sions. In any case the great mass of individuals take quite

readily the form that is presented to them.

They do not all, however, find it equally congenial,

and those are favoured and fortun ate whose potentialities

most nearly coincide with the type of behaviour selected by

their society. Those who, in a situation in which they are

frustrated, naturally seek ways of putting the occasion

out of sight as expeditiou sly as possible are well served in

Pueblo culture. Southwest institutions, as we have seen,

minimize the situations in which serious frustration can

arise, and when it cannot be avoided, as in death, they

provide means to put it behind them with all speed.

On the other hand , those who react la frustration as to

an insult and whose first thought is to get even are amply

provided for on the Northwest Coast. They may extend

their native reaction to situations in which their paddle

breaks or their canoe overturns or to the loss of relatives

by death . They rise from their first reaction of sulking to

thrust back in return , to 'fight' with property or with

weapons . Those who can assuage despair by the act of

bringing shame to others can register freely and without

conflict in this society, because thei r proclivities are deeply

channelled in their culture. In Dobu those whose first

impulse is to select a victim and project their misery upon

him in procedure s of punishment arc equally fortunate.

I! happens thar .n ons, of the three cultures we have

described meets frustration in a realisticmanner by stress-

ing the resumption of the and interrupted effilSri-

ence.' It might even s eem' iliat intlie case of death is

ITDpossible . But the institutions of many cultures never-

theless attempt nothin g less. Some of the forms the resti-

tution takes are repugnant to us, but that only makes it

clearer that in culture s where frustration is handled by

giving rein to this potential behaviour , the institutions of

that society carry thi s course to extraordinary lengths.

Among the Eskimo, when one man has killed another, the

family of the man who has been murdered may take

t

222 PATTERNS OF CULTIJIlE

the murderer to replace the loss within its own group. The

murderer then becomes the husband of the woman who

has been widowed by his act. This is an emphasis upon

restitution that ignores all other aspects of the situation-

those which seem to us the only important ones; but when

tradition select s some such objective it is quite in character

that it should disregard all else.

Restitution may be carried out in mourning situations

in ways that are less uncongenial to the standards of West-

ern civilization. Among certain of the Central A1gonkian

Indians south of the Great Lakes the usual procedure was

adoption. Upon the death of a child a similar child was

put into his place. The similarity was determined in all

sorts of ways: often a captive brought in from a raid was

taken into the family in the full sense and given all the

privileges and the tenderness that had originally been

given to the dead child . Or quite as often it was the child's

closest playmat e, or a child from another related settle-

ment who resembled the dead child in height and features.

In such cases the family from which the child was chosen

was supposed to be pleased, and indeed in most cases it

was by no means the great step that it would be under our

institutions. The child had always recognized many

'mothers' and many homes where he was on familiar foot-

ing. The new allegiance made him thoroughly at home in

still another household. From the point of view of the be-

reaved parent s, the situation had been met by a restitution

of the status quo that existed before the death of their

child.

Persons who primarily mourn the situation rather than

the lost individual are provided for in these cultures to a

degree which is unimaginable under our institutions . We

recognize the possibility of such solace , but we are careful

to minimize its conn ection with the original loss. We do

not use it as a mourning technique, and individuals who

would be well sati sfied with such a solution are left un-

supported until the difficult crisis is past.

There is anoth er possible attitude toward frustration.

It is the precise oppo site of the Puebl o attitude, and we

have described it among the other Dion ysian reactions of

the Plains Indians . Instead of trying to get past the ex-

perience with the least possible discomfitur e, it finds relief

r

THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE PATT ERN OP CULTURE 223

in the most extr avagant expres sion of grief. The Indians

of the plains capitalized the utmost indulgences and ex-

acted violent demonstrati ons of emotion as a matt er of

course.

In any group of individu als we can recognize those to

whom these differ ent rea ctions 1.9 frustration and &rid

are congeni al : ignorin g j tl. indulging it by uninhjbited

expr ession, gett ing even, pun ishing a victim, and seeking

restituti on of t he original situat ion. In the psychiatric

records of our own society, some of t . 1 ! e ~ e JmEtilSes are

recogniz ed as bad ways of dealing with the situation ,

some as good. The bad ones are said to lead to maladjust-

ment s and insaniti es, the good ones to adequate social

functi onin g. It is clear, however , that the corr elation does

not lie between any one 'bad' tendency and abnormality

in any absolute sense. The desire to run away from grief,

to leave it behind at all costs, does not foster psychotic

behaviour where, as among the Puebl os, it is mapped out

by institutions and supported by every attitude of the

group. The Pueblos are not a neurot ic people. Their cul-

ture gives the impre ssion of fostering mental health .

Similarly, the par anoid att itudes so violently expressed

among the Kwakiu tl are known in psychi atric theory

derived from our own civilizat ion as thor oughly ' bad' ;

that is, they lead in variou s ways to the br eakdown of

personali ty. But it is just t hose individuals amo ng the

Kwakiuti who find it congenial to give the freest expres-

sion to these att itudes who neverthel ess arc the leaders

of Kwakiutl society and find grea test personal fulfilment

in its cultur e.

Obviously, adequate pers onal adjustment does not

depend upon following certa in motivations and eschew-

ing others . The correlation is in a ditferent direction . Just

as those are favoured whose congenial responses are

closest to that behaviour which characterizes their society,

so those are disorient ed whose congenial respon ses faUin

that arc of behaviour which is not capitalized by their

culture . The se abnor mals arc those who are not supported

by the insti tutions of their civilizat ion. They are the excep-

tions who have not easily taken the traditi onal forms of

their culture .

For a valid compara tive psychiatry, these disoriented

224 PAlTEIlNS OF CULTURE

persons who have failed to adapt themselves adequately

to their cultures are of first importance. Tbe issue in

psychiatry has been too often confused by starting from a

fixed list of symptoms instead of from the study of those

wbose characteristic reactions are denied validity in their

society.

The tribes we bave described have all of them their non-

participating 'abnormal' individuals. The individual in

Dobu who was thoroughly disoriented was the man who

was naturally friendly and found activity an end in itself.

He was a pleasant fellow who did not seek to overthrow

his fellows or to punish them. He worked for anyone who

asked him, and he was tireless in carrying out their com-

mands. He was not filled by a terror of the dark like his

fellows, and be did not , as they did, utterly irthibit simple

public responses of friendliness toward women closely re-

lated, like a wife or sister. He often patted them play-

fully in public. In any other Dobuan this was scandalous

behaviour , but in him it was regarded as merely silly. The

village treated him in a kindly enough fashion, not taking

advantage of him or making a sport of ridiculing him, but

he was definitely regarded as one wbo was outside the

game.

The behaviour congenial to the Dobuan simpleton has

been made the ideal in certain periods of our own civiliza-

tion, and there are still vocations in which his responses

are accepted in most Western communities. Especially if

a woman is in question, she is well provided for even to-

day in our mores, and functions honourably in her family

and community. The fact tbat the Dobuan could not func-

tion in his culture was not a consequence of the particular

responses that were congenial to him, but of the chasm

between them and tbe cultural pattern.

Most ethnologists have had similar experiences in

recognizing that the persons who are put outside the pale

of society with contempt are not those who would be

placed there by another culture. Lowie found among the

Crow Indians of the plains a man of exceptional knowl-

edge of his cultural forms. He was interested in consider-

ing these objectively and in correlating different facets. He

had an interest in genealogical facts and was invaluable

on points of history. Altogether he was an ideal interpreter

I

\

TH E INDI VIDU AL AND m e P ATTE RN OP CULTURE 225

of Crow life. These traits, however , were not those which

were the password to honour among the Crow. He had a

definite shrinking from physical danger, and br avado was

the tri bal virt ue. To make matters worse he had at -

tempt ed to gain recognition by claiming a war honour

which was fraudul ent. He was proved not to have bro ught

in, as he cla imed, a picketed hor se from the enemy' s camp.

To lay false clai m to war honou rs was a paramount sin

among the Crow, and by the general opinion. constantly

reiter at ed, he was regarded as irre sponsible and incom-

petent.

Such sit uations can be paralleled with the atti tude in

our civilization towar d a man who does not succeed in

regarding personal possessions as supremely importa nt .

Our hobo population is consta ntly fed by those to whom

the accumulat ion of propert y is not a suffic ient moti vation .

In case these indi viduals ally themselves with the hoboes,

publi c opinion regards them as potentially vicious, as in-

deed because of the asocial situation into which they are

thr ust they readily become. In case, however , these men

comp ensat e by emphasizing their artist ic temper ament

and become members of expatria ted groups of petty ar-

tists, opi nion regards t.hem not as vicious but as silly.

In any case they are unsupported by the forms of their

society, and the effort to exp ress themselves satisfactorily

is ordinarily a greater task than they can achieve.

The di lemma of such an individual is often 111 0st suc-

cessfully solved by doing violence to his st rongest natural

impul ses and accepting the role the culture honour s. In

case he is a per son to whom social recognition is necessary,

it is ordina rily his onJy possible course. One of the most

stri king indi vidu als in Zuni had accepted this necessity.

In a society that thoroughly distrusts authority of any

sort , he had a native personal magnetism that singled him

out in any group. In a society that exa lts moderati on and

the easiest way. he was tur bul ent and could act violently

upon occ asion. In a society that pr aises a pliant person-

ality that 'talks lot s'- that is, th at chatters in a friendly

fashion-h e was scornful and aloof. Zuni' s only reaction

to such personalities is to br and them as witches . He was

said to have been seen peering thr ough a window from

out side, and this is a sure mark of a witch. At any rat e, he

226 PA]T ERNS Of CULTURE

got drunk one day and boasted that they could not kill

him. He was taken before the war priests who bung him

by his thumb s from the rafter s till be should confess to his

witchcraft . This is the usual procedur e in a charge of

witchcraft. However , he dispatched a messenger to the

government troop s. When they ca me, his shoulders were

already crippled for life, and the officer of the law was left

with no recourse but to imprison the war priests who had

heen responsible for the enormity. One of these war priests

was probably the most respected and important person in

recent Zufii history, and when he returned after imprison-

ment in the state penitenti ary he never resumed his

priestly offices. He regard ed his power as broken. It was

a revenge that is prob ably uniqu e in Zufu history. It in-

volved, of course, a challenge to the pr iesthoods, against

whom the witch by his act openly aligned himself.

The course of his life in the fort y years that followed

this defiance was not. however. what we might easily

predict. A witch is not barr ed from his membership in

cult groups because he has been condemned, and the way

to recognition lay thr ough such activity. He possessed a re-

markable verbal memory and a sweet singing voice . He

learned unbelievabl e stores of mythology, of esoteric ritual,

of cult songs. Many hundr eds of pages of stories and

ritual poetry were taken down from his dictation before

he died, and he regarded his songs as much marc exten-

sive. He became indispensable in ce remonial life and be-

fore he died was the governor of Zuiii . The congenial

bent of his personality threw him into irreconcilable con-

flict with his society, and he solved his dilemma by turn-

ing an incidental talent to account. As we might well ex-

pect, he was not a happy man. As governor of Zuni, and

high in his cult groups. a marked man in his community,

he was obsessed by death . He was a cheated man in the

midst of a mildly happy populace.

It is easy to imagine the life he might have lived among

the Plains Indi ans, where every institution favoured the

traits that were native to him. The personal authority,

the turbulence, the scorn, would al l have been honoured

in the career he could have made his own. The unhappi-

ness that was inseparable from his temperament as a suc-

cessful priest and governor of Zufu would have had DO

TH E INDIVIDUAL AND TIl E PATT ERN OF CUL TURE 227

pl ace as a war chi ef of the Ch eyenn e; it was not a function

of the tr ait s of his native endowment but of the sta nda rds

of the cui tur e in whic h he found no outlet for his nativ e

respon ses.

The indi vidual s we have so far di scussed are not in any

sense psychopathic . Th ey illustrate the dilemma of the

individu al whose congeni al driv es are not provid ed for in

the instituti ons of his culture. This dil emma becomes of

psychiatric import ance when the behaviour in question is

regarded as ca tego rically abnorma l in a society. Western

civilizati on tends to regard even a mild homosexual as an

abnorm al. Th e clinical pict ure of homosexualit y stresses

the neuro ses and psyc hose s to which it gives rise, and

emph asizes almost equally the inadequ ate functi onin g of

the invert and his behaviour. We have only to turn to

oth er cultur es, however , to realize that homosexuals hav e

by no means been unif orml y inadequ at e to the social

situati on. Th ey have not always failed to functi on . In

some societ ies they have even been espec ially accla imed.

Plat o' s Republic is. of course, the most co nvincing sta te-

ment of the honour abl e esta te of homosexualit y. It is

pre sent ed as a major mean s to the good life, and Plat o's

high ethical eva luation of thi s response was upheld in tbe

cust omary behaviour of Gr eece at that period .

Th e Ameri can Indi ans do not mak e Plato' s high moral

claims for homosex ua lity, but homosexuals are often re-

garded as excep t ional ly able. In most of Nort h Ameri ca

there exists the institution of the berdache, as the French

called them. Th ese men-women were men who at pub erty

or thereaft er took the dress and the occupa tions of women.

Sometimes they marri ed other men and lived with them.

Sometimes they wer e men with no inver sion , persons of

weak sexual endow ment who chose this rol e to avoid the

jeer s of the women. Th e ber daches were never regarded

as of first- rate supernatural powe r. as similar men- women

wer e in Siberi a, but rath er as leaders in women' s occupa -

tions, good healers in ce rta in diseases, or. among ce rta in

trib es, as the genial organizers of social affairs. Th ey

were usually, in spite of the mann er in which they were

accept ed, regarded with a ce rtain emba rra ssment. It was

thought slightly ridiculous to address as 'she' a person

who was known to be a man and who, as in Zufii, would

228 PATTERNS OF c ULTURe

be buri ed on the men's side of the cemetery . But they

were socially placed. Th e emphas is in most tr ibes was

upon the fact that men who took over women's occupa-

tions exce lled by reason of their strength and initiative and

we re therefore leaders in women's tech niques and in the

accumulation of those forms of property made by women.

One of the best known of all the Zunis of a generation

ago was the man- woman We- wha, who was, in the words

of his friend. Mrs. Stevenson, 'ce rtainly the strongest

person in Zuni, bot h ment all y and physically.' Hi s re-

markable memory for ritual made him a chief personage

on ceremonial occa sions. and his strength and intelli gence

made him a leader in all kinds of crafts.

The men- women of Zu fii are not all strong, self- reliant

personages. Some of t hem take this refuge to protect

themselves against thei r inability to take part in men's

activities. One is almost a simpleton, and one. hardly

more than a little boy. has del icate features like a girl's.

There are obviously several reasons why a person becomes

a berdache in Zuiii , but whateve r the reason. men who

have chosen openly to assume wome n's dress have the

same chance as any other persons to es tablish themselves

as functi onin g members of the soc iety. Their response is

socially recognized. If they have nati ve ability. they can

give it scope; if they are wea k creat ures, they fail in

terms of their weakness of character, not in terms of

their inversion .

The Indian inst itution of the berd ache was most strongly

developed on the pl ains. Th e Dakot a had a sayi ng ' fine

possessions like a berdache's,' and it was the epitome of

praise for any woman's household possessions. A ber-

dache had two strings to his bow, he was supreme in

women's techniques, and he could also support his me-

nage by the man's activity of hunt ing. Therefo re no one

was richer . When espe cially fine beadwork or dr essed

skins we re desired for ce remonial occ asions. the berdache's

work was sought in preference to any other's. It was his

soc ial adequacy that was stressed above all else. As in

Zuni. the attitude toward him is ambivalent and touched

with malaise in the face of a recogni zed incongruity.

Soci al sco rn, however, was visited not upon the berdache

but upon the man who lived with him. The latter was re-

TH E INDIVIDU AL AND TH E PArrE RN OP CULTU RE. 229

garded as a weak man who had chose n an easy berth in-

stead of the recognized goals of their culture; he did not

contribute to the household , which was already a model

for all households through the sole efforts of the berdache.

Hi s sexual adjustme nt was not singled out in the judg-

ment that was passed upon him. but in terms of his

economi c adjustment he was an outcas t.

I

When the homo sexu al response is regard ed as a per-

version , however , the invert is immedi at ely exposed to all

the conflicts to which aberra nts are always exposed. Hi s

guilt , his sense of inadequ acy, his failur es, are conse-

quences of the disr eput e which social tr aditi on visits upon

him; and few people can achieve a sat isfactory life un-

supp ort ed by the standards of the society. Th e adjustments

that society demand s of them would strain any man' s

vitalit y, and the consequences of this conflict we identify

with thei r homosexuality .

Tr ance is a similar abnorma lity in our society. Even a

very mild mystic is aberra nt in Western civilizati on . In

ord er to study tr ance or catalep sy within our own soc ial

group s, we have to go to the case hi stori es of the abnormal .

Th er efor e the corre lation bet ween tr ance expe rience and

the neur oti c and psychoti c seems perfect. As in the case

of the homosexual , however , it is a local corre lation char-

acteri stic of our centu ry. Even in our own cultural back-

ground othe r eras give dilTerent result s. In the Middle

Ages when Ca tholicism made the ecstatic expe rience the

mark of sainthood , the trance expe rience was greatly

valu ed, and those to whom the respon se was congenial,

instead of bein g overwhelmed by a cat astroph e as in our

centu ry, were given confide nce in the pursuit of their

car eer s. It was a valid ati on of ambiti ons. not a stigma of

insanit y. Indi viduals who were suscept ible to tr ance, ther e-

fore , succeeded or failed in term s of their nati ve capa c-

ities, but since tr ance expe rience was highly valued, a

great leader was very likely to be capable of it.

Among primitiv e peo ples, tr ance and cata lepsy have

been honour ed in the extr eme. Some of the Indi an tribes

of Ca lifornia accorded pr estige principally to those who

passed throu gh certa in tr ance experiences . Not all of these

tribe s beli eved that it was excl usively women who were so

blessed, but among the Shasta this was the convent ion.

230 PATTERNS OF CULTURE

Their shamans were women, and they were acco rded the

greatest prestige in the co mmunity. They were chosen be-

cause of their co nstitutional liabiJity to trance and allied

manifestations. One day the woman who was so destined,

while she was about her usual work. fell suddenl y to the

ground. She had hear d a voice spea king to her in tones of

the greatest intensity. Turning, she had seen a man with

drawn bow and arrow. He co mmanded her to sing on pain

of being shot throu gh the heart by his arrow. but under

the stress of the expe rience she fell senseless. Her family

gather ed. She was lying rigidly, hardl y br eathing. They

knew that for some time she had had dreams of a special

charact er which indi cated a shamanistic calling, dreams

of escaping grizzly bears. falling off cl iffs or trees. or of

being surrounded by swarms of yellow-jackets. The com-

munit y knew therefore what to expec t. Aft er a few hours

the woman began to moan gently and to roll about upon

the ground. tremblin g violently. She was supposed to be

repeatin g the song which she had bee n told to sing and

which durin g the tr ance had been taught her by the spirit .

As she revived, her moaning became more and more clearly

the spirit's song until at last she called out the name of

the spirit itself , and immediat ely blood oozed from her

mouth.

When the woman had come to her self after the first

encounter with her spirit. she danced that night her first

initiatory shaman's dance. For three nights she danced,

holdin g her self by a rope that was swung from the ceiling.

On the thi rd ni ght she had to receive in her body her

power from the spirit. She was dancing, and as she felt the

approach of the moment she called out, 'He will shoot me,

he will shoot me.' Her friends stood close. for when she

reeled in a kind of cataleptic seizure. they had to seize her

befor e she feU or she would di e. Fro m thi s time on she

had in her body a visible materialization of her spirit's

power. an icicl e-like object which in her dances thereafter

she would exhibit . produ cing it from one part of her body

and returning it to another part. From this time on she

continued demonstrations. and she was called upon in

great emergencies of life and death. for curing and for

divin ati on and for counsel. She became, in other words. by

this procedure a woman of great power and importance.

TH E I NDI VID UAL AND T H E PATT ERN OF CU LT UR E 23 1

It is cl ear that. far from rega rd ing catalept ic seizures as

bl ots upon the fam ily escutcheon and as evide nces of

dr eaded di sease . cu ltura l approval had seized upon them

and mad e of them the path way to autho rity over one' s

fellows. They were the outstanding cha ract er istic of the

most respected social type, the type which funct ioned

with most hon our and rewa rd in the co mmunity. It was

preci sely the cataleptic individ ual s who in thi s culture

wer e singl ed out for authority and leade rship.

Th e po ssible usef ulness of ' abno rmal' types in a soc ial

str ucture. provided they arc types that a re cult urally

selected by th at gro up. is illustrated from every par t of

the world . Th e shamans of Sibe ria do mi nate thei r com-

mu ni ties . Acco rdin g to the ideas of these peop les. they are

indi vidual s who by submission to the will of the spirits

have been cured of a grievous illness-th e onset of the

seiz ur es- and have acq uired by (his means grea t super-

nat ural power and incomparabl e vigour and hea lth . S O I 1 1 C ~

dur ing the per iod of the ca ll. arc violently insane for sev-

eral years ; others irr espo nsibl e to the po int where they

have to be co nsta nt ly wa tc hed lest they wa nder ofT in the

snow and fr eeze to deat h; others ill and emac iated to

th e po int of death. some times with bl ood y sweat. It is the

shamanistic pract ice which co ns titutes thei r cure. and

the extr eme exe rtion of a Sibe rian seance leaves them. they

claim. rested and able to enter immed iat ely upon a similar

pe rfo rmance. Ca ta leptic seizures arc regarded as an esse n-

tial part of any shamanistic per formance .

A good descr iption of the neur ot ic co ndition of the

shaman and the atte ntion given him by hi s society is an

old one by Canon Ca llaway, reco rded in the words of an

old Zulu of South Afri ca :

Th e condition of a man who is about to become a diviner

is th is : at first he is appa rent ly robu st, but in the process of

time he begins to be delica te. nOI having any rea l di sease,

but being delicate. He habitu all y avoids certa in kinds of

food, choosing wha t he likes. and he does not cat much of

that : he is cont inually co mplai ni ng of pains in diffe rent

part s of his hod y. And he tel ls them th at he h;IS drea mt that

he was carried away by a river. He dreams of many things,

and his body is muddied [as a river) a nd he become s a house

of dreams. He dreams consta nt ly of many th ings. and on

23 2 PATTERNS OF CULTURE

awake ni ng tells his fri end s. ' My body is mudd ied tod ay; I

dr eam many men wer e kill ing me, and I escaped I know

not how. On waking one pa rt of my hody felt differe nt

from other parts : it was no longer alike all over.' At last

that ma n is very ill. and they go to the div iner s to enqui re .

Th e diviners do not at once sec th at he is abou t to have a

soft head (that is, the sensitivity associa ted wit h shaman-

ism] . It is difficult for t hem la see the t r uth ; t hey con tin u-

ally t alk no nsense and mak e fal se stateme nts. until all the

man ' s ca ttle are devour ed at the ir comma nd. they saying

t hat the spirit of his people dem ands ca tt le. t hat it may eat

food . AI lengt h all t he man 's prop erty is expend ed. he

st ill be ing ill ; and t hey no longer know wha t to do. for he

has no more cat tle, and his frie nds help him in suc h things

as he needs.

At length a div iner comes and says t hat all the ot hers are

wrong. He says. ' He is possessed by t he spiri ts. Th er e is

not hing else. Th ey mo ve in him, be ing divided into two

parti es: so me say, "N o. wc do not wi sh our chi ld injured.

we do not wish it ." It is for that reason he does not get

well. If you bar the way aga inst the spirits. yo u will be

killing him . For he will no t be a divi ner; neither will he

ever be a man aga in. '

So the ma n may be ill two yea rs with out gelli ng be tter;

perh aps even longe r th an th at. He is confine d to his house.

This continues t ill his hair fall s off . And his body is dry

and scurfy: he does not like to ano int himself . He shows

that he is about to be a di viner by yawni ng agai n and aga in,

and by sneezing cont inua lly. It is appa re nt also fr om his

be ing very fond of snuff: not allowing any long ti me to

pass wit ho ut tak ing some. And peop le beg in to sec that

he has had wh at is good given to him.

Aft er t hat he is ill : he has co nvulsion s. and whe n water

has been po ured on hi m they then cease for a t ime. He

hab ituall y sheds tea rs. at first slight. then at last he weeps

aloud and when the peop le are asleep he is hear d makin g a

noise and wa kes the peopl e by his singing; he has co mposed

a song. and the me n and women awa ke and go to sing in

concert with him. All t he peopl e of the village ar c t roub led

by wan t of sleep; for a man who is becomin g a diviner

C;.l USCS great troub le. for he does not sleep. hut wo rks co n-

st ant ly with his brai n: his sleep is mer ely by sna tches. and

he wa kes up singing man y songs: and peopl e who arc near

qui t t heir villages by night when the y hear him singing

aloud a nd go to sing in concert. Perhaps he sings till

mornin g. no on e having slept. And then he leaps abo ut

THE INDIVIDUAL AND TH.E PATT ERN OF CUL TU RE 233

the bouse like a fr og; and the hou se becomes too small for

him, and he goes out leapin g and singing, and shaking like

a reed in the wat er, and drippin g wit h perspir ati on .

In thi s st ate of things they da ily expe ct his death ; he is

now but skin and bones, and th ey think th at tomorr ow's

sun will not leave him alive. At thi s time many catt le are

eaten , for the peo ple encour age hi s becomin g a diviner . At

length (in a drea m] an anci ent ancestral spirit is pointed

out to him . Thi s spir it says to him , ' Go to So-and- so and

he will churn for you an emetic [the medi cine the drinking

of whi ch is a part of sha ma nist ic init iat ion] th at you may

be a diviner altoget her.' Th en he is quiet a few days, having

gone to the di viner to have the medicine churned for him;

and he comes back quite ano ther man , being now cleansed

and a di viner indeed .

Ther eafter for life, when he is possessed by his spirits,

he foret eUs events and finds lost art icles.

It is clear that cultur e may value and make soc ially

availabl e even highl y unstabl e hum an types. If it chooses

to tre at their peculiarities as the most valued variants of

human behaviour , the indi vidual s in question will rise to

the occasion and perform their soc ial roles without refer-

ence to our usual ideas of the types who ca n make social

adjustm ent s and those who ca nnot. Th ose who function

inad equ at ely in any soc iety ar e not those with certa in fixed

' abnorma l' tr ait s, but may well be those whose responses

have received no suppon in the inst itutions of their cul-

tur e. Th e weakness of these abe t-rants is in great measure

illusory . It springs, not from the [act that they are lacking

in necessary vigour, but that they are individu als whose

native responses are not reaffirmed by society. Th ey are,

as Sapir phrases it, ' alienated from an impo ssible world.'

Th e pe rson unsupport ed by the sta nda rds of his time

and place and left naked to the winds of ridicul e has been

unfor gett ably dr awn in Eur opean liter atur e in the figure

of Don Qu ixote. Cerva ntes turn ed upon a tr adi tion still

honour ed in the abstract the limeli ght of a changed set of

pr actic al standards, and his poo r old man, the orthodox

upholder of the romanti c chivalr y of another generation,

became a simpleton. Th e windmills with which he tilted

were the serious antagonists of a har dl y vanished world,

but to tilt with them when the world no longer called

234 PATTeRNS OP CULTURE

them serious was to ra ve. He loved his Dulcinea in the

best t rad itional manner of chivalry . but another version of

love was fashi on able for the mom ent , and his fer vour was

counted to him for madn ess.

These contrasting worlds which, in the primi tive cul-

tur es we have co nside red. are sep ara ted from onc another

in space. in modern Occi de ntal history more often suc-

ceed one anot her in ti me. Th e major issue is the sa me in

eithe r case, but the impo rtance of under st and ing the phe-

nomenon is far grea ter in the modern world where we ca nnot

esca pe if we would from the succes sion of configura tions

in ti me. When eac h culture is a world in itself, relatively

stable like the Eskimo culture, for exa mple, and geo-

grap hically isolated from all othe rs. the issue is acad emi c.

But our civilization must deal with cult ura l standards that

go down under our eyes and new ones that arise from a

shadow upon the hori zon. We must be willing to take

account of changing normaliti es even when the question is

of the morality in which we we re bred . Ju st as we are

handicapped in deal ing with ethica l prob lems so long as

we hold to an absolute definition of mor alit y. so we are

handicapp ed in dealing with hum an soc iety so long as we

ident ify our local normaliti es with the inevitable necessi-

ties of existence.

No society has yet atte mpted a self-conscious direction

of the proce ss by which its new norm alities are cr ea ted

in the next generat ion. Dewey has pointed out how

possibl e and yet how drastic sueh soc ial enginee ring

would be. For some tr ad it ional arra ngements it is obvio us

that very high p rices are paid. reck oned in terms of hum an

suffering and fr ust rat ion. If these arr angement s presented

themselves [Q us merely as arra nge me nts and not as cate-

gorical imperatives. our reasonable course would be to

adap t them by whatever means to rat ionally selecte d goals.

What we do instead is to rid icu le our Don Qui xotes. the

ludicr ous embod iments of an outmod ed tr aditi on. and con-

ti nue to regard our own as final and presc ribed in the na-

ture of things.

In the meant ime the ther apeut ic prob lem of dealing

with our psychopat hs of [his type is often misunderstood.

Their ali enati on from the actual worl d can often be more

intelligentl y hand led than by insist ing tha t the y adopt

TH E IND rvmuAL AND TH E PATT ERN OP CUL TU RE 235

th e mod es that are al ien to them . Two ot her courses are

alway s po ssible. In the first place, the misfit individu al

may cultivate a gre ater objective inter est in his own pref-

erences and learn how to manage wit h greater equa-

nimi ty his de viat ion from the type. If he learn s to recog-

nize the extent to which his suffering has been due to his

lack of suppo rt in a tr aditi on al ethos , he may gradually

edu cat e himsel f to accept his degree of difference with less

suffering. Bot h the exaggerated emotiona l distu rbances of

the mani c-depr essive and the secl usion of the schizo-

phr en ic add certa in va lues to existence which arc not

open to those di ffer entl y co nstituted . The unsup port ed indi-

vidu al who vali antly acce pts his favourit e and nat ive

virt ues may atta in a feasible course of be hav iour that

makes it un necessary for him to take refuge in a pri vate

worl d he ha s fashi on ed for himself . He may gradua lly

achieve a mor e indepe nd ent and less to rt ured attitude

towar d his deviations and upon this att itude he may be

able to buil d an adequately func tioning existence.

In the second place . an increased tolerance in soc iety

towar d its less usual types must keep pace with the self-

educat ion of the patient. Th e po ssibilit ies in this di rec-

tion are endless. Tradi tion is as neur ot ic as any pati ent ;

its overgrown fear of deviation from its fort uitou s stand-

ard s conforms to all the usual definitions of the psycho-

path ic. This fear does not depend upon observation of the

limit s within whic h conformity is necessary to the soc ial

good . Much mor e deviat ion is allowe d to the individual

in some cult ures than in othe rs. and those in which much

is al lowed can not be shown to suffer from their pec uliarity.

It is prob able th at soc ial orde rs of the futur e will carry

this tol erance and encourageme nt of ind ividua l diffe rence

much fur ther than any cult ures of which we have exper-

ience.

Th e Am eric an tend ency at the present time lean s so far

to the op pos ite extreme that it is not easy for us to pic-

tur e the changes that suc h an att itud e wo uld br ing abo ut.

Mid dtetown is a typic al example of our usual urban fear

of seeming in however slight an act different from our

neighbours. Ecce nt rici ty is mor e fear ed than pa rasitism.

Every sacrifice of ti me and tr anquilli ty is made in order

that no one in the fami ly may have any tai nt of noncon-

236 PATTERNS OF CULTU RE

formity attached to him. Children in school make their

great tragedies out of not wearing a ce rtain kind of stock-

ings, not joining a ce rtain dancing-class, not driving a

certain car. The fear of being different is the dominating

motivation recorded in Middletown.

The psychopa thic toll that such a motivation exacts is

evident in every institution for mental diseases in our

country. In a soc iety in which it existed only as a minor

motive among many others, the psychi atric picture would

be a very different one. At all events, there can be no

reasonable doubt that onc of the most effective ways in

which to deal with the stagg.ering burden of psychopathic

tragedies in America at the present time is by means of

an educational program which fosters tol erance in society

auad a kind and indepe nde nce that is for eign- _

to Middletown an our urban traditions.

Not all psychopath s, of course, are indi viduals whose

native responses are at variance with those of their civi-

lization. Another large group are those who are merely in-

adequate and who are strongly enough motivated so that

their failure is more than they can bear. In a society in

which the will-to-power is most highly rewar ded, those

who fail may not be tho se who are differentl y const ituted,

but simply those who are insufficientl y endowed. The in-

feriority complex takes a great toll of suffering in our

society. It is not necessary that sufferers of this type have

a history of frustration in the sense that strong native

bent s have been inhibi ted ; their frustr ation is often enough

only the reflection of their inability to reach a certain goal.

There is a cultural implication here, too, in that the

traditional goal may be access ible to large numbers or to

very few, and in proportion as success is obse ssive and is

limited to the few, a greater and greater number will be

liable to the extreme penal ties of maladju stment.

To a certain extent, therefore, civilization in setting

higher and possibly more wort h-while goals may increase

the number of its abnormals. But the point may very

easily be ove remphasized. for very small changes in social

attitudes may far outweigh this correlation. On the whole,

since the socia l possibilities of tolerance and recognition

of individual difference are so little explored in practice,

pessimism seems premature. Certainly other quite differ-

THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE PATI ERN OP CULTURf! 237

ent social factors which we have just discussed are more

dir ectl y respon sibl e for the grea t propo rt ion of our neu-

rotics and psychotics, and with these other factors civiliza-

tions could , if they would , deal with out necessary intrinsic

loss.

We have been conside ring indivi du als from the point

of view of their ability to funct ion ad equately in their

society. Thi s adequate functioning is one of the ways in

whi ch norm alit y is clini call y defined. It is also defined in

term s of fixed symptoms, and the tend ency is to identify

normality with the statistically average. In practice this

average is one arrived at in the laboratory, and devaitions

from it are defined as abnormal.

From the point of view of a single culture thi s pro-

cedure is very useful. It shows the clinical pictur e of the

civilization and gives considerable information about its

soci ally approved behaviour. To generalize this as an

absolute normal, however, is a different matter. As we

have seen, the range of normality in different cultures does

not coincide. Some, like Zufii and the Kwakiutl, are so far

removed from each other that they overlap only slightly.

The statistically determined normal on the Northwest

Coast would be far outside the extreme boundaries of

abnormal ity in the Pueblos. The norm al Kwakiutl rivalry

co ntest would only be under stood as madness in Zufii,

and the traditional Zuni indifference to dominance and

the humili ati on of others would be the fatu ousness of a

simplet on in a man of nobl e famil y on the Northwest

Coas t. Aberrant behaviour in either culture could never

be determined in relation to any least common denorni-

nator of behaviour. Any soc iety. according to its major

preoccupations, may increase and intensify even hysteri-

cal, epileptic, or paranoid symptoms, at the same time

relying socially in a greater and grea ter degre e upon the

very indi vidu als who di splay them.

Thi s fact is important in psychiatry because it makes

clear anothe r gro up of abnorma ls which pro bably exists

in every culture: the abnormals who represent the extreme

developm ent of the local cultu ral type. This group is

soc ially in the opposite situation from the group we have

discussed. those whose responses are at variance with their

cultural standards . Soc iety, inst ead of exposing the former

238 PATT ERNS OF CULTURE

group at every point , supports them in their furth est aber-

rations. They have a licence which they may almost end-

lessly exploit. For this reason these persons almost never

fall within the scope of any contempo rary psychiat ry.

They are unl ikely to be described even in the most careful

manuals of the generat ion that foster s them. Vet from

the point of view of another generation or culture they are

ordinarily the most bizarr e of the psychopathic types of

the period .

The Purit an divines of New England in the eighteenth

century were the last persons whom contemporary opinion

A.in the colonies regarded as psychopath ic. Few prestige

II\ groups in any culture have been allowed such complete

intellectual and emot ional dict at orship as they were. They

were the voice of God. Yet to a modem obse rver it is

they, not the confu sed and torment ed women they put to

death as witches, who were the psychoneurotics of Puritan

New England . A sense of guilt as ext reme as they por-

trayed and demanded both in their own conversion experi-

ences and in those of their converts is found in a slightly

saner civilization only in institutions for mental diseases.

They admitted no salvation without a conviction of sin

that prostrated the victim. sometimes for years, with re-

morse and terrible anguish. It was the duty of the minister

to put the fear of hell into the heart of even the youngest

child, and to exact of every convert emotional acceptance

-' of his damnation if God saw fit to damn him. It does not

matt er where we turn among the records of New England

>-Purit an churches of this period, whether to those dealing

-: with witches or with unsaved children not yet in their

teens or with such themes as damnation and predestina-

tion, we are faced with the fact that t he group of people

who carried out to the greatest extreme and in the fullest

honour the cultural doctrine of the moment are by the

slightly alte red standards of our generation the victims of

intolerable aberrations. From the point of view of a com-

V par ative psychiatry they fall in the category of the ab-

normal .

In our own generation extreme tonns of ego-l ratifica-

tion are culturally supporte<l In a SImilar fashIon. ITO ant

and unbridled egoists as family men, as officers of the law

and in business, have been again and by

TH E INDIVID UAL AND TH E PATTERN OF CULTURE 239

_novelists and dramati sts, and they are famili ar in every

community. Like me- behaviour of Puritan divines , tneir

cour ses of action ar e often mor e asocial than those of the

inmat es of penit entiaries. In terms of the suffering and

frustr ation that they spread about them tbere is probably

no comp ari son. Th ere is very possibly at least as great a

degre e of mental warping . Yet they are entrusted with

positions of great influence and importan ce and arc as a

rule father s of families. Their impre ss both upon their

own childr en and upon the structur e of our society is

indelible. They are not described in our manuals of psy-

chiatry because they are supported by every tenet of our

civilization. The y ar e sure of themselves in real life in a

way that is possible only to those who are oriented to the

point s of the compass laid down in their own culture .

Neverth eless a future psychiatry may well ransack our

novels and lett ers and public records for illumination

upon a type of abnormality to which it would not other-

wise give credence. In every society it is :lmong this very

group of the culturally. and forti fied that some

" of the most extreme types of hum"an behaJlour ar e

fostered.

Social thinkin g at the present time has no mor e im-

portant task befor e it than that of takin g adeq uate ac-

count of cultur al relati vity. In the fields of bot h .ociology

and psychology the impli cations are funda mental. and

modern thought about contacts of peoolcs and about our

changing standards is grea tly in need of sane and scientific

directi on. The sophisticated modern temper has made of

social relativit y. even in the small area which it has recog-

nized, a doctrin e of despai r" It has pointed nut its in-

congruit y with the ort hodox dreams of per manence and

ideality and with the individu al' s illusions of autonomy.

It has argued that if human expe rience must give up these,

the nut sheU of existence is empty. g ut to interpr et our

dilemma in these terms is to be guilty of an anachronism.

It is only the inevitabl e cultur al lag that makes us insist

that the old must be discover ed again in the new, that

there is no solution but to find the old cer tainty and stabil-

ity in the new plasticit y. Th e recognition of cultural rel-

ativit y ca rr ies with it its own v alues, WhLCh need not be

.those 6n he PfQIosoph}Os._n c.haU""nges custom-

240 PATTERNS OP CULTURE

ary opinions and causes those who have been br ed to them

'acute discomf ort . It rouses pessimism heca us e jt throws

old formul ae into co nfusion....ll.o. Lbecause, it- cont ains any-

thing intrinsically difficult. As soo n as the new opinion

is embraced as customary belief. it will be another trusted

bulwark of the good life. We shall arr ive then at a more

realistic soc ial faith, accep ting as grounds of hope and as

new bases for tolerance the coex isting and equally valid

patterns of life which mankind bas created for itself from

the raw materials of ex istence.

REFERENCES

CHAPTE R I

PAGE

26 Hard , Jean -Mar c-Gaspar d . Th e Wild Boy 0/ Avey ron, tr ans-

lated by Geo rge and Muri el Hum phr ey. New Yo rk, 1932.

It is probable that some of these children wer e subnor mal

an d abandone d beca use of that fact. But it is hard ly possible

th at all of th em were, ye t they all impressed obse rvers as

half -witt ed .

28 See Boas. Fra nz. A nthropolog y and M od ern L if e, 18-100 .

New York, 1932.

CHAPTE R Il

36 For an analysis of pubert y rites as crisis ceremonialism,

Van Ge nnep. Arn old. Lex Rit es de Passage. Pari s, 1909.

39 Mead , Ma rgaret. Co ming 0/ Age in Samoa. New York,

1928. 1949.

42 Howitt , A. W. Th e Nativ e Tri bes of Sou th-East A ustralia.

New York . 1904 .

47 Benedict, Ruth . Th e Concept of the Gua rdian Spirit in North

Am eri ca . Memoi rs of the Am erican A nt hr opological Asso-

ciati on, no. 29, 1923.

CHAPTER III

SS Malin owski , Broni slaw. Th e Sexu al Li fe of Savages, London,

1929; Argona uts of the Western Pacific, Lond on , 1922; Crime

and Custom in Savage Soci ety, London, 1926; Sex and

Repr ession in Savage Societ y. London, 1927; Myth in Primi-

tive Psychology, New York, 1926.

Stem, Wil he1m. Die differ entie lle Psychologie in thren Gr und-

lagen . Leipzig, 1921.

56 w orrtn ger , Wi1helm . Form in Gothi c. London , 1927.

Koffka, Ku rt . The Gr owth of the Mind. New Yor k, 1927.

Kdhl er, Wilhelm . Gesta lt Psychology . New York , 1929 .

Fo r a summary of the wor k of the Ges ta lt school see

Mu rph y, Ga rdner. Approaches to Personality, 3-36. New

York , 1932.

S7 Dilth ey, Wilbelm . Gesam me lte Schr ii ten, Band 2; 8. Leipzig,

1914- 31.

58 Spengler, Oswald. The Decl ine of the West , New York,

1927-28.

241

242 PATTERNS OP CULTURE

CHAPTER IV

PAGB

62 Th e tra ditional spe lling, Zuiii , is misleadi ng. The " is pro-

nounced as in any English wo rd.

The foll owing is a selected bibliogra phy on Zuiii. The refer-

ences in this chapter are numbered as in this list.

Benedict . Ruth .

l. Zutii Mythol ogy. Colum bia University Cont ribu tions to

Anthro pol ogy , 2 vol., XXI . New York. 1934.

2. Psychological T ypes in the Cult ures of the Sou thwest.

Proceedin gs of th e Twen ty- thir d Internationa l COIIKress

of Ame ricanis es, 5728 1. New York, 1928.

Bunzel . Ruth L.

1. Introd ucti on to Zufii Ce remon ialism. Forty-Seve nth An-

nual Report 0/ the Bureau 0/ American Ethnol ogy, 467-

544. Was hingto n, 1932.

2. Zuiii Rilual Poetry. I bid. 6 11-835.

3. Zuiii Katchin as . Ibid. 837- 1086.

4. Zufu Texts . Publi cati ons 0/ the Ame rican Ethnol ogical

Society , XV . New York, 1933.

Cushing, Frank Hamilt on.

1. Outlin es of Zuni Creation Myths. Thi rteenth Annua l

Report 0/ the Bureau 0/ Am erican Ethn ology. Washing-

ton, 1926.

2. Zuni Fo lk Tales. New York , 1901.

3. My Experi ences in Zuiii. Th e Century Magazin e, n.s.

3, 4. 1888.

4. Zuiii Bread st uffs. Publicat ions 0/ the Mu seum 0/ the

Am erican l nd ian, Hev e Found at ion, VII I. New York , 1920.

5. Zuni Fetishes. Sec ond A nnual Report 0/ the Bur eau 0/

Am erican Etbnotogv. Washin gton . 1883.

Kro cber , A. L. Zuii i Kin and Cla n. A ntbr opo logi cal Pap ers

0/ the Am erican M us eum 0/ Natural History , vol. XV III,

part 2. New York, 191 7.

Parson s. EIsie Clews. Notes O D Zufii, I and n. Memoirs 0/

the Ame rican Anthr opol ogi cal As socia tion, vol. 4. DO. 3,

1927.

Stcvenson, Matilda Cox.

1. Th e Zuff Indian s. Twen ty -Th ird A nnuat Rep ort 0/ the

Bureau 0/ Am er i can ,lIn %1: Y. Washin gton. 1904 .

2. The Religiou s Lif e of the l uni Child . Ibid., V. Wash-

ington, 1887.

62 Kidder. A. V. So ut h wes t A rctur oi ogy , Yale Univers ity Pr ess.

New Haven, 1934.

66 Zufii ritual pr ayer s ar e recorded in Bunzel 2.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Perspectives on Culture and RationalityDocument29 paginiPerspectives on Culture and RationalityMichelle Taton HoranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary Of "Malinovski's Theory Of Needs" By Ralph Piddington: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESDe la EverandSummary Of "Malinovski's Theory Of Needs" By Ralph Piddington: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESÎncă nu există evaluări

- The University of Chicago Press The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, PolicyDocument14 paginiThe University of Chicago Press The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, PolicyLucas Martín DanessaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Defense of Ethical RelativismDocument4 paginiA Defense of Ethical RelativismEvangelina MazurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultures Merging: A Historical and Economic Critique of CultureDe la EverandCultures Merging: A Historical and Economic Critique of CultureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Socialism EinsteinDocument12 paginiWhy Socialism Einsteingt295038100% (1)

- Why SocialismDocument4 paginiWhy SocialismiddaggerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Diversities Postwar WorldDocument8 paginiCultural Diversities Postwar WorldpetacsilvestruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture Communication and SilenceDocument20 paginiCulture Communication and SilencerogarhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dynamics of CultureDocument3 paginiDynamics of CultureCarandang, Krisha Mae R. -BSBA 2DÎncă nu există evaluări

- SociologyDocument14 paginiSociologyGhulam muhammad100% (1)

- Why SocialismDocument12 paginiWhy SocialismLuis De FrancaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 2Document48 paginiLesson 2Lerah MahusayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture and Human SocietyDocument11 paginiCulture and Human SocietyM Abdillah JundiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sapir - Culture Genuine SpuriousDocument30 paginiSapir - Culture Genuine SpuriousJamie MccÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nkeonye Otakpor: Philosophic A 53 (1994, 1) Pp. 57-71Document15 paginiNkeonye Otakpor: Philosophic A 53 (1994, 1) Pp. 57-71Nestor MajnoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Factors in Social Work Practice and Education1: Florence Rockwood KluckhohnDocument10 paginiCultural Factors in Social Work Practice and Education1: Florence Rockwood KluckhohnFilipeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Sociology: The AmericanDocument29 paginiJournal of Sociology: The Americankayivih694Încă nu există evaluări

- S. Abd Al-Latîf - Principles of Islamic CultureDocument66 paginiS. Abd Al-Latîf - Principles of Islamic Cultureaedicofidia0% (1)

- UCSP Q1-M3 Bergonio. Sophia 12-ABMDocument10 paginiUCSP Q1-M3 Bergonio. Sophia 12-ABMLianna Jenn WageÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gre Issue Wrting ExamplesDocument34 paginiGre Issue Wrting ExamplesshardulkaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- MODULE 4 (Art and Anthropology - Cultural Relativism)Document47 paginiMODULE 4 (Art and Anthropology - Cultural Relativism)micaela.camama14Încă nu există evaluări

- Balkin, J. M. (1998) - Cultural Software. A Theory of Ideology. Yale University Press.Document394 paginiBalkin, J. M. (1998) - Cultural Software. A Theory of Ideology. Yale University Press.Raul TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aspects of CultureDocument29 paginiAspects of CultureBecky GalanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- E. Shils Mass SocietyDocument28 paginiE. Shils Mass SocietyDavid CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Culture Shapes Behavior and SocietiesDocument9 paginiHow Culture Shapes Behavior and SocietiesRussel LiwagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethnocentrism PDFDocument6 paginiEthnocentrism PDFIman GraincaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auxtero - Thought Piece (Meta-Ethics)Document1 paginăAuxtero - Thought Piece (Meta-Ethics)Sean AuxteroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brahmastra 2Document4 paginiBrahmastra 2ramesh babu DevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Action For Freedom: Paulo FreireDocument12 paginiCultural Action For Freedom: Paulo FreireAna BudićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Freire - Cultural Action For FreedomDocument12 paginiFreire - Cultural Action For FreedomMartaMartitaMarchesiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Page 6 Soc Sci 2Document1 paginăPage 6 Soc Sci 2Hope Earl Ropia BoronganÎncă nu există evaluări

- On High and Popular Culture by Raymond WilliamsDocument4 paginiOn High and Popular Culture by Raymond WilliamsShinriel KudorobaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How high and popular culture intersectDocument8 paginiHow high and popular culture intersectAlyssa Mae EstacioÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is SolidarityDocument6 paginiWhat Is SolidarityGardenofLight AltaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spivak - 2006 - Culture AliveDocument2 paginiSpivak - 2006 - Culture AliveIsabela Umbuzeiro ValentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural RelativismDocument2 paginiCultural RelativismDesiree BartolomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nations and Nationalism: Basil BlackwellDocument11 paginiNations and Nationalism: Basil BlackwellelviraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Universidad Abierta para Adultos (UAPA) : AsignaturaDocument11 paginiUniversidad Abierta para Adultos (UAPA) : AsignaturaFawaldy Gomez RoqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structuralism and Popular CultureDocument17 paginiStructuralism and Popular Culturemerve sultan vuralÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Society AND Politics: CultureDocument41 paginiUnderstanding Society AND Politics: CultureLerah MahusayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Titus Burckhardt - What Is Conservatism ?Document7 paginiTitus Burckhardt - What Is Conservatism ?Cosmin IvașcuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural RelativismDocument13 paginiCultural RelativismAnny TodaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory of Pseudo CultureDocument24 paginiTheory of Pseudo Culturewilliam_diaz_4Încă nu există evaluări

- How Culture WorksDocument28 paginiHow Culture WorksCarlos AfonsoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phillips What Makes Cultures SpecialDocument7 paginiPhillips What Makes Cultures Specialmuchacho77Încă nu există evaluări

- CASE STUDY Culture, Governance and Underdevelopment in BangladeshDocument6 paginiCASE STUDY Culture, Governance and Underdevelopment in BangladeshcseijiÎncă nu există evaluări

- ANTH3 Turner ReadingDocument11 paginiANTH3 Turner ReadingGrace D'ArcyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definitions of SocietyDocument5 paginiDefinitions of SocietytrulyblessedmilleÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Incubation of Sociological IsolationDocument2 paginiThe Incubation of Sociological IsolationOmar Alansari-KregerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bee Larvae and Onion Soup BA 1Document2 paginiBee Larvae and Onion Soup BA 1saptarshi bhattacharjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Stories Which Civilisation Holds As SacredDocument9 paginiThe Stories Which Civilisation Holds As SacredChris HesterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aimé Césaire - Culture and ColonizationDocument18 paginiAimé Césaire - Culture and ColonizationrewandnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social ActionDocument23 paginiSocial ActionInga TroņinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- On High and Popular CultureDocument5 paginiOn High and Popular CultureBlaženka JurenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Sociology and Anthropology Module 2Document10 paginiIntroduction To Sociology and Anthropology Module 2Happy Balagtas VillegasÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Reading Letter To The Galatians 3:7-14Document4 paginiFirst Reading Letter To The Galatians 3:7-14Buddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marion and LevinasDocument20 paginiMarion and LevinasBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- SET A - 2013 (February, April, June, August, October and December)Document4 paginiSET A - 2013 (February, April, June, August, October and December)Buddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perspectives in Biology and Medicine Summer 2004 47, 3 Proquest Research LibraryDocument16 paginiPerspectives in Biology and Medicine Summer 2004 47, 3 Proquest Research LibraryBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marion and JamesDocument11 paginiMarion and JamesBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- David BidneyDocument25 paginiDavid BidneyBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization and Culture-Tom PalmerDocument30 paginiGlobalization and Culture-Tom PalmerBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes From UndergroundDocument119 paginiNotes From UndergroundBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Franz Josef WetzDocument22 paginiFranz Josef WetzBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marion and Badieou Re ReductionDocument10 paginiMarion and Badieou Re ReductionBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ratzinger On ManDocument9 paginiRatzinger On ManBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1 - The Act of PhilosophizingDocument12 paginiLecture 1 - The Act of PhilosophizingBuddy Seed100% (2)

- Man and Person by John Paul IIDocument10 paginiMan and Person by John Paul IIBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literacy Through LiberationDocument6 paginiLiteracy Through LiberationBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heschel Philosophy of ManDocument11 paginiHeschel Philosophy of ManBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- GadamerDocument21 paginiGadamerBuddy SeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy of Man Hand Out 6Document5 paginiPhilosophy of Man Hand Out 6ANNALENE OLITÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hybrid Beamforming For DFRC System Based On SINR Performance MetricDocument6 paginiHybrid Beamforming For DFRC System Based On SINR Performance MetricRAVI SHANKAR JHAÎncă nu există evaluări

- 715-Article Text-1157-1-10-20210725Document8 pagini715-Article Text-1157-1-10-20210725Abraham Bruce CalvindoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medica2023 ExhibitorsDocument288 paginiMedica2023 ExhibitorsHamza BadraneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advances in Water Polllution Monitoring and ControlDocument185 paginiAdvances in Water Polllution Monitoring and Controlantonioheredia100% (1)

- Classroom Management For Young Learners - Modul 3Document2 paginiClassroom Management For Young Learners - Modul 3wahyu agustinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Letter To BenefactorDocument2 paginiA Letter To BenefactorJeremy JM88% (8)

- Advanced Result: Unit 1 Test: (10 Marks)Document3 paginiAdvanced Result: Unit 1 Test: (10 Marks)Edu Lamas GallegoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Session 6Document57 paginiSession 6Jose Julio Flores BaldeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Política de Seguridad, Protección, Salud, Medio Ambiente y Relaciones Comunitarias (SSHEC) - 2474877Document1 paginăPolítica de Seguridad, Protección, Salud, Medio Ambiente y Relaciones Comunitarias (SSHEC) - 2474877Angel Del CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test 1 CHM256 - Question Paper - 231105 - 121107Document7 paginiTest 1 CHM256 - Question Paper - 231105 - 121107Aqilah NajwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psych Stats CIA-2030206 Method FileDocument39 paginiPsych Stats CIA-2030206 Method FileAranya BanerjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit I - UV-vis Spectroscopy IDocument10 paginiUnit I - UV-vis Spectroscopy IKrishna Prasath S KÎncă nu există evaluări

- Age and Gender With Mask ReportDocument15 paginiAge and Gender With Mask Reportsuryavamsi kakaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Danpal Compact BrochureDocument8 paginiDanpal Compact BrochureErik FerrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electroanalysis experiments scan rates and copper concentrationDocument2 paginiElectroanalysis experiments scan rates and copper concentrationRaigaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colosseum Code of Conduct Procedure - Chinese RevDocument4 paginiColosseum Code of Conduct Procedure - Chinese Revhrdhse. WanxindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- KSH13007 KSH13007: SEMIHOW REV.A1, Oct 2007Document6 paginiKSH13007 KSH13007: SEMIHOW REV.A1, Oct 2007Manolo DoperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statement of Purpose or Motivation LetterDocument2 paginiStatement of Purpose or Motivation LettersalequeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bernoulli's EquationDocument13 paginiBernoulli's EquationAbdul Azeez Ismaila ShuaibuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 9 - Curvature and Refraction, Measuring Vertical DistancesDocument11 paginiLesson 9 - Curvature and Refraction, Measuring Vertical DistancesJohn Andrei PorrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Part (2-A) - Fundamentals of Open Hole Logging-Abbas Radhi 2020Document223 paginiPart (2-A) - Fundamentals of Open Hole Logging-Abbas Radhi 2020Ali ElayawiÎncă nu există evaluări

- HISTORY OF MEDICINEDocument2 paginiHISTORY OF MEDICINEMonsour SalazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experiment 1 Moment of Inertia and Angular MomentumDocument3 paginiExperiment 1 Moment of Inertia and Angular MomentumRikachuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Comm Lab Report SignalsDocument11 paginiData Comm Lab Report SignalsRafiur Rahman ProtikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epsy For Edpm Chapter 3,4 &5Document22 paginiEpsy For Edpm Chapter 3,4 &5mekit bekeleÎncă nu există evaluări

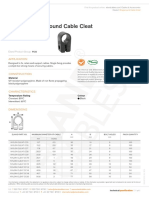

- Wraparound Cable CleatDocument1 paginăWraparound Cable Cleatsaghaee.rezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING-II SHEAR STRENGTH OF SOILSDocument26 paginiGEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING-II SHEAR STRENGTH OF SOILSHamza RizviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arksolv - 04-TR - SDS - ENDocument14 paginiArksolv - 04-TR - SDS - ENTimuçin ÇolakelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instant Download Ebook PDF Dynamics of Structures 5th Edition by Anil K Chopra PDF ScribdDocument41 paginiInstant Download Ebook PDF Dynamics of Structures 5th Edition by Anil K Chopra PDF Scribdlisa.vanwagner713100% (44)

- Indigo (The Search For True Understanding and Balance)Document197 paginiIndigo (The Search For True Understanding and Balance)Trunk Boolean100% (1)