Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Europe's Macro-Regions, 13 April 2010

Încărcat de

CMRC_ASDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Europe's Macro-Regions, 13 April 2010

Încărcat de

CMRC_ASDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Europes Macro-Regions Integration through territorial co-operation

F o r u m at t h e Co m m I t t e e o F t h e r e g I o n s , B r u s s e l s

13 April 2010

Conference Brochure

ForeWorD

xperimentation and cooperation is an everyday practice at the local and regional level in order to go further in the European integration project and to improve the living conditions of our citizens. With this spirit, the Committee of the Regions is pro-actively contributing to the open laboratory of the new EU macro-regional strategies.

The goals are those established by the Treaty: the development through a better economic, social and territorial cohesion. To achieve those goals, the macro-regional strategies are among the most interesting innovative instruments. They are focusing on the territory, trying to integrate sector-specific policies, offering the possibility of multi-level governance. They also can benefit from strategic proposals and the implementation of projects under the European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC). Success depends on us. It depends on the positive outcome of the pilot experience of the Baltic Sea Region strategy and the one expected on the Danube strategy. It depends on how the EU institutions together will deal with the expectations regarding the other proposals which are emerging in different EU regions. For the macro-regional strategies, the Committee of the Regions, as a political assembly, intends to be the carrier of the initiative, as a guardian of equal access and promoter of multi-level governance. mercedes Bresso President of the Committee of the Regions

he European Union must make better use of territorial co-operation as a tool to foster cross-border and transnational integration. We should put in place an overall EU strategy to provide a framework for territorial cooperation activities of all kinds, including macro-regions. Approaches and objectives will vary from region to region, depending on the specific needs for strengthened cross-border cooperation.

The common principle should be to add value to existing activities. An integrated approach with coordination of actions across policy areas will usually achieve better results than individual initiatives, and where groups of countries and regions choose to come together to achieve common goals, this will also strengthen EU cohesion. Johannes hahn Commissioner for Regional Policy

Europes Macro-Regions Integration through territorial co-operation

for macro-regions?

D

ebates about territorial cohesion, a term now endorsed by the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, and multi-level governance have evolved in recent years. Most influential have been the adoption of a Territorial Agenda by the Member States in 2007, the publication of a Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion by the European Commission in 2008, and the adoption of the White paper on Multilevel Governance by the Committee of the Regions in 2009. These documents have stressed the need for better coordination and enhanced cooperation across borders, policy areas and different levels of government. The EU strategies for macro-regions, still under experimentation, may represent one of the new instruments to achieve better EU cooperation and, thus, contribute to EU territorial cohesion. With the development of the European Unions Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region, a new concept came into being in the European Union. The term macro-regions has been used in an international context to describe globally significant groups of nations or groupings of administrative regions within a country. But with the pilot EU Strategy of the Baltic Sea Region, the European Commission now describes a macro-region as an area including territory from a number of different countries or regions associated with one or more common features or challenges. Macro-regions are imagined communities which have no independent political status or no institutions and which do not overshadow other regional or national identities. Although a macro-region can be identified by common features or

What are the eU strategies

challenges, its frontiers are not necessarily precisely defined. Physical boundaries may vary according to the type of problem being tackled at a macro-regional level. These regions might overlap, so a functioning region can be part of one or more macro-regions. The creation of an EU macro-regional strategy stems from this definition. The Baltic Sea Strategy, launched in June 2009 by the European Commission and endorsed by the European Council in October 2009, is now regarded as a model for other potential

Regional and local authorities in the European Union must be taken into account, since they represent 16% of the EUs GDP, one third of public expenditure, two thirds of total public investment and 56% of public employment. Governance of the European Union should play a more active and leading role in local and regional entities at all stages of the policy cycle, from defining the requirements to drafting, applying, supervising and evaluating the measures. manuel Chaves Third Vice-President of the Spanish Government and Minister of Territorial Policy

It is clear that this cooperation offers us many possibilities. It provides a valuable contribution to the EUs Territorial Agenda, to the territorial cohesion of the Union, and to a more effective implementation of the EUs Regional Policy. Danuta hbner Chairwoman of the European Parliaments Committee on Regional Development

macro-regional approaches. For a second region, along the Danube, the European Council asked the European Commission in June 2009 to present an EU strategy before the end of 2010. This development has inspired discussions in other regions too, such as the North-Sea-English Channel region, the Alpine region, the Adriatic and Ionian, and the Atlantic Arc. In addition, similar questions and approaches have been discussed with the Union for the Mediterranean. According to present thinking about macro-regions, strategy implementation would not involve extra financial resources compared to what is already available in a region from various sources. Moreover, it would not involve setting up new institutions or extending the powers of existing administrative bodies. At the same time, it is important to establish responsibility and accountability at EU level and there are calls that the European Commission should play a facilitating role in EU macro-regional strategies.

Further reading

Committee of the regions: www.cor.europa.eu The role of local and regional authorities within the new Baltic Sea strategy, own-initiative opinion, CdR 381/2009; Rapporteur: Uno Aldegren An EU strategy for the Danube area, Opinion, CdR 149/2009; Rapporteur: Wolfgang Reinhart Website on EGTCs: www.cor.europa.eu/egtc White Paper on Multilevel Governance (June 2009) EU macro-regional strategies and European governance; seminar (26 November 2009) european Parliament European Union strategy for the Baltic Sea Region and the role of macro-regions in the future cohesion policy Draft report by the European Parliaments Committee on Regional Development, (March 2010), REGI/7/01786: Rapporteur: Wojciech Micha Olejniczak European Parliament resolution of 21 January 2010 on a European Strategy for the Danube Region, P7_TAPROV(2010)0008

european Commission Regional Policy DG: www.europa.eu/regional_policy Macro-regional strategies in the EU A discussion paper by the European Commission (2009) Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion: Turning territorial diversity into strength, COM(2008) 616 Website on the Baltic Sea Region: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/cooperation/baltic Website on the Danube Region: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/cooperation/danube/ DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries: http://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/index_en.html european Council Presidency Conclusions, Brussels European Council, 18/19 June 2009 Council Conclusions on the European Union Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region, 15018/09, 27 October 2009 Regional approaches to management of water and the marine environment, including implementation of the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region - Council conclusions, 17797/09, 22 December 2009

4 4

Europes Macro-Regions Integration through territorial co-operation

activities of the Committee of the regions

he Committee of the Regions (CoR), the EUs assembly of local and regional representatives, takes a special interest in the development of EU strategies for macro-regions. During the new political mandate 2010-2015, the CoR Commission for Territorial Cohesion (COTER) will analyse in depth and develop the horizontal political orientation on the overall macroregional approach. Furthermore, CoR members have demonstrated their political commitment by forming intergroups around emerging macroregions in order to discuss issues of common interest and to feed their views into the policy-making process of the EU. As its input into the Baltic Sea Region Strategy, the CoR assessed the role of local and regional authorities and is now in the process of formulating an opinion on the strategy itself, including recommendations for future development. The CoR also played an important role in pushing forward with a strategy for the Danube area, and it has already proposed concrete fields of action for the Danube Strategy, underlining the key role of regions and cities in its planning and implementation. The Cors White Paper on multilevel governance, adopted in June 2009, argues that macro-regions must be supported by a form of multilevel governance. According to the CoR, this innovative approach to cross-border cooperation requires a high level of coherence in its design and integration within the European process. The lessons learnt from macro-regional strategies will be essential in the context of European governance, the development of territorial cooperation and the objective of territorial cohesion. Cross-border cooperation is a fundamental element for the success of the EU strategies for macro-regions. The european grouping of territorial Cooperation (egtC) is one of the most valuable tools to integrate the territories beyond national boundaries. Implemented by the Regulation (EC)1082/2006, the EGTC enables regional and local authorities from different Member States to set up cooperation groupings with a legal personality. An EGTC may organise and manage cross-border, transnational or interregional cooperation measures with or without a financial contribution from the EU. So far, ten EGTCs have been set up and more than 25 are under preparation: the Amphictyony EGTC (Greece, Cyprus, Italy and France) the Duero-Douro EGTC (Portugal and Spain) the Eurodistrict Strabourg-Ortenau EGTC (France and Germany)

Macro-regional strategies raise stimulating questions. Would they provide us with strategic platforms to develop more efficient transport networks in between neighbouring countries and, at the same time, preserve fragile ecosystems across borders? Can we make better use of community funds which are allocated to a pre-defined area without falling into the trap of centralisation? Do we have to seek to cover the entire territory of Europe? Do we need to avoid overlaps of areas? How many strategies will consequently have to be adopted in this planning period? And what are the conditions of access? Do we have common understanding of the dynamics of territorial development of the Union? Answers are necessary for all these different questions that are very closely linked to the effectiveness of the strategy and the search for fair treatment of all territories. mercedes Bresso President of the Committee of the Regions

the Euroregion Pyrnes-Mditrane EGTC (Spain and France) the Galicia-Norte Portugal EGTC (Portugal and Spain) the Ister-Granum EGTC (Hungary and the Slovak Republic) the Karst-Bodva EGTC (Hungary and the Slovak Republic) the Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai EGTC (France and Belgium) the West-Vlaanderen/Flandre-Dunkerque-Cte dOpale EGTC (Belgium and France) the Zasnet EGTC (Portugal and Spain). The Committee of the Regions seeks to facilitate cooperation and networking among existing and emerging EGTCs through such means as a web-based platform, elaborates studies and contributes to the dissemination of information and the exchange of experiences. An own-initiative opinion on EGTC is currently under preparation.

the BaLtic sea region

n recent years, there has been increased interest in the concept of the Baltic Sea Region as a geographical entity with its own identity. This is generally taken to mean the eight EU Member States (Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Germany) surrounding the Baltic together with Norway, Belarus and the north-western parts of the Russian Federation. These countries have always been trading partners. Between the 13th and 17th centuries, the area formed one of the strongest economic networks in Europe. But despite this common cultural and historical legacy, the region is characterised by significant demographic, economic and geographic disparities. The growing importance of the Baltic Sea regional approach reflects the belief that the different states in the area are being confronted with a number of common challenges and developments, which can best be dealt with through new forms of regional cooperation. The most important common challenge lies in how to manage the Baltic Seas marine environment.

The eu strategy for the Baltic sea region was launched by the European Commission in June 2009 and subsequently adopted by the European Council in October 2009. The European Commission consulted the different stakeholders involved while preparing the strategy. These stakeholders have now been given an ongoing opportunity to participate in the further development of the strategy, for example in the framework of an annual forum. The strategy focuses on issues that cannot be solved by national or local means alone. The establishment of the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region marked the first time that the EU had developed such a comprehensive strategy for a macroregion. Although the strategy itself does not have its own funding, between 2007 and 2013 projects will receive funds under the regional policy and other EU funding. The strategy is centred on four main pillars and 80 flagship projects grouped into 15 priority areas, and has the following objectives:

The BalTic Sea Region: facTS and figuReS total population:100 million sea surface area: 377,000 km Drainage basin area: 1.3 million km Coastline: about 8,000 km average depth of sea: 58 metres annual cargo traffic: 822 million tons annual oil traffic: 171 million tons largest city: Saint Petersburg

Source: DG REGIO, Wikipedia

6 6

Europes Macro-Regions Integration through territorial co-operation

Creating a sustainable environment

Some ideas in the strategy build on actions already taken in the region to reduce the negative impact on the environment from different sources, for example by removing phosphates from detergents and by encouraging best practices that minimise fertiliser run-off. A total of 9.8 billion has been earmarked for this purpose, including 3.1 billion to process waste water.

Increasing prosperity

Actions include boosting trade and improving the quality of education services by encouraging people to move freely throughout the region in order to pursue knowledge or to teach. Available funding for this objective amounts to 6.7 billion, including 2.4 billion for stimulating innovation.

making the region accessible and attractive

The strategy sets out ways in which to complete traffic and energy interconnections between the Baltic states and the wider region, and supports, for example, major improvements to the rail network. A total of 27.1 billion has been made available, of which 500 million will be invested in the regions gas and electrical infrastructure, and 23.1 billion in transport networks.

safety and security

The action plan suggests ways to coordinate the fight against organised crime by integrating existing organisations and stimulating cooperation, for example in the field of maritime law enforcement through an integrated network of surveillance systems for all maritime activities. To this end, 697 million has been earmarked. The Committee of the Regions supported the creation of the Baltic Sea Strategy at EU level from the very start. In its opinion of April 2009, prepared by CoR member uno aldegren, it emphasised that the Baltic region is particularly well suited for being a pilot for the introduction of a macro-regional strategy, and that the strategy can serve as a model for other potential macro-regions. The opinion stresses the need to involve local and regional authorities at all stages of decision making. The CoR sees the trend towards macro-regions as a logical consequence of EU enlargement and a development that merits encouragement. It stresses that even though the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region is essentially an internal affair amongst eight Member States, it is a development that can open the door to stepping up cooperation with nonEU countries, in this case the Russian Federation, Norway and Belarus. Since the need for cooperation in the areas of environmental issues, transport, logistics and national security issues transcends the EUs external borders, the CoR therefore believes that significant consideration should be given to this external dimension when implementing the strategy.

For me the Baltic Sea is a unique macro-region in Europe for economic, environmental and emotional reasons. The economic dimension is clear: for most of the Member States around the Baltic Sea, this macro-region is the most important export market for goods produced in these countries and its regions. Therefore, a well functioning transport system on land and on sea as well as excellent communication facilities are vital. We have many common expectations for the future such as the rapid development of new energies on and off shore. The environmental situation is also a key: we need functioning ecosystems to preserve biodiversity as well as the basis for our fishing industry and the well being of our people. A Clean Baltic Sea Area could be a best practice example for all of Europe. And, like me, many love to live in the Baltic Sea area. The Baltic Sea links the different bordering regions. A continuous exchange of ideas, innovations and traditions has supported mutual understanding over the centuries. I want to go further along this line with my colleagues from the Committee of the Regions in the years to come. uno aldegren Member of the Executive Committee of the Skne Region, Sweden, Chairman of the CoR Intergroup Baltic Sea Regions

The external dimension also features as an important element in the CoRs draft report on the Baltic Sea Strategy. Prepared by CoR member Pauliina haijanen and due to be adopted in April 2010, the report concludes that regions and local communities can have an important role to play in implementing this external dimension, because they are already involved in a large number of partnerships with their counterparts in non-EU countries. Generally, it is indispensable to give a prominent role to regional and local players, because these represent the levels closest to the citizens, and because these players have sound, first-hand knowledge of the conditions and needs in the Baltic Sea Region. This approach would improve the visibility of the strategy, which is a key requirement for its success. So far, however, responsibility for the implementation of priority areas and flagship projects has been allocated primarily to Member States and not to the regions. The Committee of the Regions recommends that regions and local authorities should be given the opportunity to play a more active part in the future.

the danUBe region

T

he Danube is one of the European continents most important arteries, touching Germany, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Serbia, Romania, Croatia, Bulgaria, Moldova and Ukraine. This makes the Danube area not only an important part of Europe economically and culturally, but also environmentally. It is the longest river in the European Union. Since Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, the Danube has become an internal EU waterway. As one of the TransEuropean corridors it represents a priority axis for inland waterway traffic across the Union. The Rhine-Danube corridor provides a direct link between the North Sea and the Black Sea. Improving navigability for cargo, in a more environmentallyfriendly manner, is an important challenge. The Danube Basin is also rich in bio-diversity. Its wetlands host many breeds of wild birds and the islands provide rich habitats for many species. For instance, the Danube Delta is home to 70% of the worlds population of white pelicans. However, the waters of the Danube are no longer quite as blue as the waltz suggests and pollution is a real threat to this wildlife. Efforts to establish new water treatment plants, with the support of cohesion policy, will contribute to the improvement of water quality. The potential for economic development in the area is strong since the river provides a variety of resources for business in the form of transport and logistics as well as for tourism and culture. Trips down the Danube are proving popular With the start of the public consultation on the Danube area on 2 February 2010, the European Commission declared its wish to move from words to action on its way to a Danube strategy. In my opinion, this is a remarkable step for the whole region and at the same time an important challenge for all of us to build the strategy together and to strengthen its visibility at European level. Indeed, this work will mainly be done not by declarations, but by concrete projects and by exchange between people from different nations, regions and local authorities. Our objective must be to bring about a common awareness for this unique region that motivates people to engage actively in the Danube area. Peter straub President of the Baden-Wrttemberg State Assembly and Chairman of the CoR Intergroup Danube

The danuBe Region: facTS and figuReS Population in the basin: 83 million Catchment area: 817,000 km length of the river: 2,860 km International navigation: 2,411 km average water discharge: 6,500 m/sec. annual cargo traffic: 100 million tons largest city: Budapest

Source: DG REGIO, Wikipedia

8 8

Europes Macro-Regions Integration through territorial co-operation

with tourists and operators who are seeking to boost the regions profile. Tourist operators are considering developing a specific Danube label, which will increase the visibility and attractiveness of the region. In June 2009, the European Council formally requested the European Commission to prepare an EU Strategy for the Danube Region by the end of 2010. The European Commission started a public consultation with relevant stakeholders, including regions, municipalities, international organisations, economic partners and civil society. Initially, the Commission envisaged three pillars for the strategy: to improve connectivity and communication systems (covering in particular transport, energy issues and the information society); to preserve the environment and to protect against natural risks; and to reinforce the potential for socio-economic development In the past few years the CoR has repeatedly highlighted the particular importance of the Danube area in Europe and has called for the development of an EU Danube strategy. At the initiative of the president of the regional assembly of BadenWrttemberg and former CoR president Peter straub, an interregional group on the Danube area was set up at the end of 2008. This group brings together regional and local representatives from regions along the Danube in Germany,

Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, as well as guest members from Croatia and Serbia. Its goal is to boost the visibility of the Danube area in Brussels and to represent the interests of the regions involved at European level. In October 2009, the Committee of the Regions presented a report on an EU strategy for the Danube area, proposing concrete fields of action and underlining the central role of regions and cities in its planning and implementation. The report was prepared by Wolfgang reinhart, European affairs minister of the State of Baden-Wrttemberg and adopted at the CoR plenary session in October 2009. The blue band of the Danube has always connected people, cities and regions across borders. In addition, the Danube area brings together EU Member States, candidates for accession and neighbouring countries. Building on their practical experiences within the framework of existing cooperation and networks, the CoR is proposing concrete fields of action for the Danube strategy. The scope of the suggested measures ranges from the development of transport infrastructure and crossborder cooperation in flood protection to joint concepts for sustainable tourism and culture. Seeing the Danube area as a single major unit is also a prerequisite for its sustainable economic development. The CoR has pointed out that in the current 2007-2013 structural funds programming period the Danube area is split into two overlapping development areas, and has therefore called on the EU institutions to treat it as one single unit in the next period. 9

engLish channeL area

T

he seven EU countries (Sweden, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and the United Kingdom) plus Norway that encircle the North Sea and the English Channel share a long and eventful history. Control over, and access to the North Sea has played a pivotal part in the history of this part of Europe. The area quickly became one of the main centres of international commerce in the western hemisphere, and was of key strategic importance in the expansion of, for example, the Dutch and British empires. After World War II, the North Sea-English Channel area traded its military and geopolitical role for a solely economic one. It has since grown to be one of the busiest maritime regions in the world, home to some of the worlds biggest cargo ports such as Rotterdam, Hamburg and Antwerp. Over 400 ships pass through the Straits of Dover every day and also the Kiel Canal, connecting the North Sea to the Baltic, is another shipping route with heavy traffic. The southern parts of the North Sea are Europes main fishery, with fishing being a major economic factor for many of the bordering regions and the whole North Sea is an important source for oil and gas exploitation. Furthermore, its coasts are a major tourist destination. The major economic development of the region, however, has brought with it serious consequences for the environment. Fish stocks have been depleted drastically in recent decades as a consequence of eutrophication, continued overfishing, the introduction of alien species and heavy construction on coastal breeding grounds. Dense maritime traffic has also led to a greater accident rate, which is one of the reasons behind the high number of oil spills occurring in the North Sea. According to some estimates, up to 100 000 tons of oil are dumped or otherwise leaked into the North Sea every year. Illegal and accidental pollution from other hazardous chemical substances is a serious concern too, posing a threat to humans as well as to the larger North Sea ecosystem, with birds and marine mammals most affected. The North Sea has some of the most diverse coastal habitats in the world, ranging from large fjords to sandy beaches and marsh lands, home to a wide variety of animal and plant life. Much of the greater European drainage basin eventually flows into the North Sea, which means that its economic and environmental problems are closely related to those of western and northern Europe.

north sea-

Since its foundation in February 2009, the CoR-Intergroup North Sea-English Channel concentrated its work on strengthening the co-operation of the regions in the North Sea-Channel area. Its main focus is the development of a North Sea-Channel Strategy which is embedded in the broader discussion of macro-regional concepts on EU-level and intends to create a new level of cooperation between the supranational Community, the Member States and the regions around the North Sea and the Channel. The North Sea-English Channel part of the conference, which was organised in close co-operation with the North Sea Commission (NSC) of the CPMR, will provide the opportunity to discuss the initiative with politicians from the regions, representatives from the European institutions and stakeholders. Moreover, the conference will allow the exchange of experience with the advanced strategies for the Baltic Sea and the Danube region. hermann Kuhn Member of the regional assembly of Bremen and Chairman of the CoR Intergroup North Sea-English Channel

10 10

Europes Macro-Regions Integration through territorial co-operation

noRTh Sea-engliSh channel aRea: facTS and figuReS Population in the area: 88 million sea surface area: 645,000 km Coastline: about 41,200 km average depth of sea: 91 metres largest port city: Rotterdam

Based on figures provided by members of the North Sea-Channel Intergroup

Interest in increased cooperation at macro-regional level has been fuelled by the growing concern over these problems and a recognition of the need to come up with effective responses to these challenges.. The North Sea states share a common interest and identical objectives with regard to the regions socio-economic and ecological development. The prospect of closer cooperation on the control and conservation of fisheries, sustainable energy production, pollution reduction, coastal management and maritime research seems both necessary and beneficial for all the players involved. The CoR Intergroup on the North SeaEnglish Channel, as a first step in the push for an integrated EU strategy, has suggested the following key objectives for a regional strategy: Protection of the North Sea/Channel area as an ecological system; Adaptation to climate change; Use of the economic potentials of the area; Development of maritime resources, e.g. maritime research; Transport and energy interconnections.

For the states in the North Sea-English Channel area, the macro-regional approach is an opportunity to focus their common aims and interests, to coordinate them with their regional neighbours and to make the common concerns public at European level. According to the CoR Intergroup, the North Sea-Channel area still cannot rely on cooperation structures such as those that have grown up in the Baltic Sea Region over several decades. Neither the characteristic cooperation between the old and the new EU Member States nor the institutionalised cooperation with Russia can be transferred to the North Sea-Channel area. Compared to the Baltic Sea Region with Russia as its partner, cooperation with Norway is of importance to the North Sea-Channel area but natural circumstances, history as well as economic and social structures are different. Any North Sea-Channel Strategy will therefore clearly differ from the Baltic Sea Region Strategy by following its own priorities. Furthermore, it is necessary to examine whether the macro-regional concept is the right approach for the North Sea-Channel area or if other concepts or instruments should be preferred.

11

13 April 2010, Committee of the Regions, Brussels, Rue Belliard 101

Europes Macro-Regions Integration through territorial co-operation

On 13 April 2010, the Committee of the Regions will welcome more than 300 regional representatives, experts and other stakeholders from existing and emerging macro-regions to discuss issues related to strategy development and other themes of common interest. Organised in the context of the existing EU strategies for macro-regions and those under debate, the following questions will be addressed: What lessons can be drawn from existing and emerging macro-regional strategies? What is the role of local and regional authorities in the development and implementation of macro-regional strategies? To which extent can macro-regions be comprehensive in their approach, covering several policy areas? Should macro-regions become a means to deliver significant EU funding? What can macro-regions deliver in terms of economic and environmental benefits? More information and the proceedings of the event can be found at: www.cor.europa.eu/macroregions

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Photo credits: Fotolia/Jakub Niezabitowski: p.3, Spanish Government: p.3, European Parliament: p.4, Heinz Dieter Galonska: p.6, Fotolia/Jerome Delahaye: cover page, p.8 Committee of the Regions: p.2, p.5, p.7, p.8, p.10 European Commission: p.2, p.9, p.11 Conference brochure 2010 12 p. 21x29,7 cm Printed at the Committee of the Regions in Brussels, Belgium

Published in April 2010 Committee of the Regions Directorate for Communication, Press and Protocol Rue Belliard 101 B-1040 Brussels www.cor.europa.eu

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Eurogroup: How a secretive circle of finance ministers shape European economic governanceDe la EverandThe Eurogroup: How a secretive circle of finance ministers shape European economic governanceÎncă nu există evaluări

- EU Macro-Regions and Macro-Regional Strategies - A Scoping StudyDocument44 paginiEU Macro-Regions and Macro-Regional Strategies - A Scoping StudyDesiree ClarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Landscape dimensions: Reflections and proposals for the implementation of the European Landscape ConventionDe la EverandLandscape dimensions: Reflections and proposals for the implementation of the European Landscape ConventionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gov Macro Strat enDocument10 paginiGov Macro Strat enMiskoVesnaDjukanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic and Political Motivations of European Mini-StatesDe la EverandEconomic and Political Motivations of European Mini-StatesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cross-Border Cooperation: European Neighbourhood & Partnership InstrumentDocument9 paginiCross-Border Cooperation: European Neighbourhood & Partnership InstrumentBalan ElenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Han Ovra 2000Document37 paginiHan Ovra 2000Nemultumit de MulteÎncă nu există evaluări

- 221 Sinop Final DeclarationDocument3 pagini221 Sinop Final Declarationmihaela_oboroce6888Încă nu există evaluări

- European Union Regional Policy (Eng) / Política Regional de La Unión Europea (Ing) / Europar Batasuneko Eskualde Politika (Ing)Document6 paginiEuropean Union Regional Policy (Eng) / Política Regional de La Unión Europea (Ing) / Europar Batasuneko Eskualde Politika (Ing)EKAI CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- TerritorialAgenda2030 201201Document28 paginiTerritorialAgenda2030 201201Vera MarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 Polreg-Mai03 GBDocument20 pagini11 Polreg-Mai03 GBTheodore KoukoulisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principes CEMAT AnglaisDocument37 paginiPrincipes CEMAT AnglaisJonar LamdaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baltic Sea StrategyDocument38 paginiBaltic Sea StrategyGr_gory_Molnar_9936Încă nu există evaluări

- Eu Cohesion PolicyDocument10 paginiEu Cohesion PolicySue JamesonÎncă nu există evaluări

- C 21120090904en00010027.pdf - enDocument27 paginiC 21120090904en00010027.pdf - enRockStar ReadyToWinÎncă nu există evaluări

- EU Regional Policy in The New FinancialDocument10 paginiEU Regional Policy in The New FinancialShito RyuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ESPON Synthesis Report IIDocument80 paginiESPON Synthesis Report IIoliÎncă nu există evaluări

- EUSDR ACTION PLAN SWD202059 Final 1Document84 paginiEUSDR ACTION PLAN SWD202059 Final 1Laura HaragaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report Urban Agenda2017 enDocument36 paginiReport Urban Agenda2017 enJesús R RojoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arctic Plicy - FInal EssayDocument5 paginiArctic Plicy - FInal EssayMaria PÎncă nu există evaluări

- TA2030 Jun2021 enDocument29 paginiTA2030 Jun2021 enAlinaRoxanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Reports Submitted by The Member States On Cohesion Policy 2007-2013: Questions and AnswersDocument5 paginiStrategic Reports Submitted by The Member States On Cohesion Policy 2007-2013: Questions and AnswersjohnbranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pact of AmsterdamDocument36 paginiPact of AmsterdamTWGAScÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orientation Paper Central Europe 2021-2027: Transnational Cooperation ProgrammeDocument19 paginiOrientation Paper Central Europe 2021-2027: Transnational Cooperation Programmeskribi7Încă nu există evaluări

- European Regional Development Policies: History and Current IssuesDocument29 paginiEuropean Regional Development Policies: History and Current IssuesAnonymous OEnoXMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Plan Stratcom PDFDocument5 paginiAction Plan Stratcom PDFDaniel SolisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Key Messages: Towards A New European Neighbourhood PolicyDocument4 paginiKey Messages: Towards A New European Neighbourhood Policyapi-175173630Încă nu există evaluări

- Enpi Eastern RSP enDocument30 paginiEnpi Eastern RSP enAlina ManduÎncă nu există evaluări

- EN EN: Commission of The European CommunitiesDocument34 paginiEN EN: Commission of The European Communitiesrudolf744Încă nu există evaluări

- Regions and Cities in A Challenging WorldDocument204 paginiRegions and Cities in A Challenging WorlddmaproiectÎncă nu există evaluări

- Euip-Pgpp Term Paper: Submitted By: Abhishek VS Roll No: 183308009Document10 paginiEuip-Pgpp Term Paper: Submitted By: Abhishek VS Roll No: 183308009Abhishek V SÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBCMed NewsletterDocument2 paginiCBCMed NewsletterEugenio OrsiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Panama Natural ResourcesDocument80 paginiPanama Natural Resourcesgreat2readÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hand Policy Recommendations-EnDocument7 paginiHand Policy Recommendations-EnRéka BaloghÎncă nu există evaluări

- COM 2023 7 EN ACT Part1 v3Document23 paginiCOM 2023 7 EN ACT Part1 v3Iulian StoianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report Urban Agenda2017 en PDFDocument13 paginiReport Urban Agenda2017 en PDFJesús R RojoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Western Balkans and The EU EnlargementDocument16 paginiWestern Balkans and The EU Enlargementmswdwf100% (1)

- Time To Reset The European Neighborhood PolicyDocument26 paginiTime To Reset The European Neighborhood PolicyCarnegie Endowment for International PeaceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Urban Policy EUDocument27 paginiUrban Policy EUAng PariotiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transport Working PaperDocument11 paginiTransport Working PapervasseokÎncă nu există evaluări

- The EU Strategy For Central Asia at Year One: Neil Melvin & Jos BoonstraDocument10 paginiThe EU Strategy For Central Asia at Year One: Neil Melvin & Jos BoonstraeliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Referat Engleza 1Document7 paginiReferat Engleza 1Roxana SamsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Présidence Espagnole - MalagaDocument20 paginiPrésidence Espagnole - Malagagaubert_nicolas5765Încă nu există evaluări

- Ter-Handbook OnlineDocument192 paginiTer-Handbook OnlineEva Viorela SfarleaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Policy Paper - The Other Transatlantic Relationship and The Multilateral SystemDocument4 paginiPolicy Paper - The Other Transatlantic Relationship and The Multilateral SystemGino Figueroa MoscosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The-Impact-of-Cohesion-Policies-on-Croatia's-Regional-Policy-and-Development Iskustva I Razvoj SLOVENIJEDocument23 paginiThe-Impact-of-Cohesion-Policies-on-Croatia's-Regional-Policy-and-Development Iskustva I Razvoj SLOVENIJEVesna ČovićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Urban PolicyDocument50 paginiPrinciples of Urban PolicyNourhan El ZafaranyÎncă nu există evaluări

- EN EN: European CommissionDocument31 paginiEN EN: European Commissionngungo12345678Încă nu există evaluări

- Ipa 2 ProposalDocument27 paginiIpa 2 ProposalErald QordjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CEPS Activities Report 2010-2011Document40 paginiCEPS Activities Report 2010-2011kathamailÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toledo Informal Ministerial Meeting On Urban Development Declaration Toledo, 22 June 2010Document17 paginiToledo Informal Ministerial Meeting On Urban Development Declaration Toledo, 22 June 2010Jesús R RojoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Plan On Urban MobilityDocument15 paginiAction Plan On Urban MobilitymkarasahinÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Northern Dimension For EU PoliciesDocument8 paginiA Northern Dimension For EU PoliciesGreg LewinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Aspects of The Implementation of EU Funds 2007-2013 in Poland - Practice and ChallengesDocument9 paginiLegal Aspects of The Implementation of EU Funds 2007-2013 in Poland - Practice and ChallengesIda MusialkowskaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4cr enDocument226 pagini4cr enOana AvramÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Urban Dimension in Community Policies For The Period 2007-2013Document24 paginiThe Urban Dimension in Community Policies For The Period 2007-2013emilolauÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Spirit Vol1 EngDocument96 paginiEuropean Spirit Vol1 EngAna Maria CroitoruÎncă nu există evaluări

- The European Council: Agenda Setting in Ebbs and FlowsDocument5 paginiThe European Council: Agenda Setting in Ebbs and Flowsapi-322540214Încă nu există evaluări

- Greening Sustainable Development StrategiesDocument34 paginiGreening Sustainable Development StrategiesadauÎncă nu există evaluări

- R I P S K, C, L, E U: Egional Nnovation Olicy of Outh Orea Ompared With AND Earning From THE Uropean NionDocument41 paginiR I P S K, C, L, E U: Egional Nnovation Olicy of Outh Orea Ompared With AND Earning From THE Uropean NionLam TranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bakker y Morinville 2013 PDFDocument19 paginiBakker y Morinville 2013 PDFMaximiliano Bolados ArratiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory Based Evaluation: Past, Present, and FutureDocument19 paginiTheory Based Evaluation: Past, Present, and FutureAlberto ComéÎncă nu există evaluări

- Force To Service? Consumerist Identities in Contemporary Police GovernanceDocument5 paginiForce To Service? Consumerist Identities in Contemporary Police GovernancenooraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 15 Governing The Global Political EconomyDocument12 paginiChapter 15 Governing The Global Political EconomyMeldaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 ANU SPIR HandbookDocument19 pagini2014 ANU SPIR HandbookasfdasfdasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Slovak Balkan Public Policy Fund: Collection of Selected Policy PapersDocument123 paginiSlovak Balkan Public Policy Fund: Collection of Selected Policy PapersBalkan Civil Society Development NetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeffery 2000Document23 paginiJeffery 2000Ruxandra CucuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regional Economic Organizations and Conventional Security ChallengesDocument221 paginiRegional Economic Organizations and Conventional Security ChallengeskaraheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brunet-Jailly, 2005-Theorizing BordersDocument18 paginiBrunet-Jailly, 2005-Theorizing BordersahceratiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Europe 2020: Multi-Level Governance in ActionDocument8 paginiEurope 2020: Multi-Level Governance in ActionAndrei PopescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- OCDE Building Competitive Regions Strategies and Governance - UnlockedDocument141 paginiOCDE Building Competitive Regions Strategies and Governance - UnlockedD'Arjona ValdezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook On Theories of GovernanceDocument16 paginiHandbook On Theories of GovernanceBenjie SalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cairney 2020 - Understanding Public Policy - 2 Edition - Front MatterDocument20 paginiCairney 2020 - Understanding Public Policy - 2 Edition - Front MatterLucas100% (1)

- Peters FDocument18 paginiPeters Ferocamx3388Încă nu există evaluări

- Multi-Level Governance - Eduard Ongaro, Anthony Zito, Simona Piattoni PDFDocument371 paginiMulti-Level Governance - Eduard Ongaro, Anthony Zito, Simona Piattoni PDFMeliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forests 09 00533 v2Document17 paginiForests 09 00533 v2Villasol clasesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Socio-Economic Function of Borders EDocument289 paginiThe Socio-Economic Function of Borders ELiviu AndrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- PAD603 Handouts PDFDocument99 paginiPAD603 Handouts PDFSHAHRUKH KHAN100% (1)

- MLG - IndonesiaDocument9 paginiMLG - IndonesiaBima FitriandanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluating Integrated Impact Assessments - A Conceptual FrameworkDocument26 paginiEvaluating Integrated Impact Assessments - A Conceptual FrameworkBianca RadutaÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEd 104 MIDTERMS REVIEWERDocument12 paginiGEd 104 MIDTERMS REVIEWERYasmin Digal0% (1)

- Transportation Research Part A: Sebastian Hoffmann, Johannes Weyer, Jessica LongenDocument18 paginiTransportation Research Part A: Sebastian Hoffmann, Johannes Weyer, Jessica LongenJEFF PUPIALESSÎncă nu există evaluări

- CES Open Forum 13: CORRUPTION, INEQUALITY AND TRUST: The Greek Vicious Circle From Incremental Adjustment To "Critical Juncture" ?Document36 paginiCES Open Forum 13: CORRUPTION, INEQUALITY AND TRUST: The Greek Vicious Circle From Incremental Adjustment To "Critical Juncture" ?Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard UniversityÎncă nu există evaluări

- KJAER, Poul - A New Type of Conflicts LawDocument13 paginiKJAER, Poul - A New Type of Conflicts LawAriel de MouraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies Volume Issue 2015 (Doi 10.1080 - 1369183X.2015.1103036) Hampshire, James - Speaking With One Voice - The European Union's Global Approach To Migration and MobilDocument17 paginiJournal of Ethnic and Migration Studies Volume Issue 2015 (Doi 10.1080 - 1369183X.2015.1103036) Hampshire, James - Speaking With One Voice - The European Union's Global Approach To Migration and MobilMihai MihaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- European IntegrationDocument71 paginiEuropean Integrationstefania0912Încă nu există evaluări

- Delegated Governance and The British State (Oxford) PDFDocument383 paginiDelegated Governance and The British State (Oxford) PDFMihaelaZavoianuÎncă nu există evaluări

- TCW MidtermDocument112 paginiTCW MidtermChelsa BejasaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Border Management and Migration Control PDFDocument69 paginiBorder Management and Migration Control PDFnk1347Încă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Public Policy Theories and Issues 2nbsped 1137545194 9781137545190 CompressDocument503 paginiUnderstanding Public Policy Theories and Issues 2nbsped 1137545194 9781137545190 Compress松平定信100% (1)

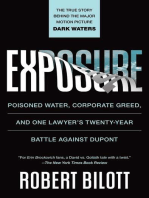

- Exposure: Poisoned Water, Corporate Greed, and One Lawyer's Twenty-Year Battle Against DuPontDe la EverandExposure: Poisoned Water, Corporate Greed, and One Lawyer's Twenty-Year Battle Against DuPontEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (18)

- Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the PoorDe la EverandSlow Violence and the Environmentalism of the PoorEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5)

- The Cyanide Canary: A True Story of InjusticeDe la EverandThe Cyanide Canary: A True Story of InjusticeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (52)

- Art of Commenting: How to Influence Environmental Decisionmaking With Effective Comments, The, 2d EditionDe la EverandArt of Commenting: How to Influence Environmental Decisionmaking With Effective Comments, The, 2d EditionEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- Environmental Justice in New Mexico: Counting CoupDe la EverandEnvironmental Justice in New Mexico: Counting CoupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty SecretDe la EverandWaste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty SecretEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Principles of direct and superior responsibility in international humanitarian lawDe la EverandPrinciples of direct and superior responsibility in international humanitarian lawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction to Ecology and Environmental Laws in IndiaDe la EverandIntroduction to Ecology and Environmental Laws in IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reduce, Reuse and Recycle : The Secret to Environmental Sustainability : Environment Textbooks | Children's Environment BooksDe la EverandReduce, Reuse and Recycle : The Secret to Environmental Sustainability : Environment Textbooks | Children's Environment BooksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Desperate: An Epic Battle for Clean Water and Justice in AppalachiaDe la EverandDesperate: An Epic Battle for Clean Water and Justice in AppalachiaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Environmental Justice: Issues, Policies, and SolutionsDe la EverandEnvironmental Justice: Issues, Policies, and SolutionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the WorldDe la EverandThe Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the WorldEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Debunking Creation Myths about America's Public LandsDe la EverandDebunking Creation Myths about America's Public LandsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Down to the Wire: Confronting Climate CollapseDe la EverandDown to the Wire: Confronting Climate CollapseEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (8)

- 3rd Grade Science: Life Sciences in Eco Systems | Textbook EditionDe la Everand3rd Grade Science: Life Sciences in Eco Systems | Textbook EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land Divided by Law: The Yakama Indian Nation as Environmental History, 1840-1933De la EverandLand Divided by Law: The Yakama Indian Nation as Environmental History, 1840-1933Încă nu există evaluări

- The People's Agents and the Battle to Protect the American Public: Special Interests, Government, and Threats to Health, Safety, and the EnvironmentDe la EverandThe People's Agents and the Battle to Protect the American Public: Special Interests, Government, and Threats to Health, Safety, and the EnvironmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Education in Practice: Concepts and ApplicationsDe la EverandEnvironmental Education in Practice: Concepts and ApplicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Busted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DDe la EverandBusted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (7)

- Ecosystem Facts That You Should Know - The Forests Edition - Nature Picture Books | Children's Nature BooksDe la EverandEcosystem Facts That You Should Know - The Forests Edition - Nature Picture Books | Children's Nature BooksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dawn at Mineral King Valley: The Sierra Club, the Disney Company, and the Rise of Environmental LawDe la EverandDawn at Mineral King Valley: The Sierra Club, the Disney Company, and the Rise of Environmental LawEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (334)

- Exposure: Poisoned Water, Corporate Greed, and One Lawyer's Twenty-Year Battle against DuPontDe la EverandExposure: Poisoned Water, Corporate Greed, and One Lawyer's Twenty-Year Battle against DuPontEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (9)

- Obstacles to Environmental Progress: A U.S. perspectiveDe la EverandObstacles to Environmental Progress: A U.S. perspectiveÎncă nu există evaluări