Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cases For Prelims

Încărcat de

Jaidee SanchezDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cases For Prelims

Încărcat de

Jaidee SanchezDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

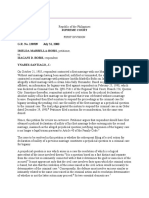

IMELDA MARBELLA-BOBIS vs. ISAGANI BOBIS GR No.

138509 July 31, 2000 FACTS: On October 21, 1985, respondent Isagani Bobis contracted a first marriage with Ma. Dulce Javier. With said marriage not yet annulled, nullified nor terminated, he contracted a second marriage with herein petitioner Imelda Marbella (on Jan. 25, 1996), and a third marriage with certain Julia Hernandez, thereafter. Petitioner then filed a case of bigamy against respondent on Feb. 25, 1998, at the RTC of Quezon City. Thereafter, respondent initiated a civil action for the declaration of absolute nullity of his first marriage license. He then filed a motion to suspend the criminal proceeding for bigamy invoking the civil case for nullity of the first marriage as a prejudicial question to the criminal case. The RTC granted the motion, while petitioners motion for reconsideration was denied. ISSUE: Whether or not the subsequent filing of a civil action for declaration of nullity of a previous marriage constitutes a prejudicial question to a criminal case for bigamy. HELD: Any decision in the civil case the fact that respondent entered into a second marriage during the subsistence of a first marriage. Thus, a decision in the civil case is not essential to the determination of the criminal charge. It is therefore not a prejudicial question. Respondent cannot be permitted to use his malfeasance to defeat the criminal action against him. A prejudicial question is one which arises in a case the resolution of which is a logical antecedent of the issue involved therein. It is a question based on a fact distinct and separate from the crime but so intimately connected with it that it determines the guilt or innocence of the accused. It must appear not only that the civil case involves facts upon which the criminal action is based, but also that the resolution of the issues raised in the civil action would necessarily be determinative of the civil case. Consequently, the defense must involve an issue similar or intimately related to the same issue raised in the criminal action and its resolution determinative of whether or not the latter action may proceed. Its two essential elements are (a) the civil action involves an issue raised in the criminal action; and (b) the resolution of such issue determines whether or not the criminal action may proceed. In the case at bar, the respondents clear intent is to obtain a judicial declaration of nullity of his first marriage and thereafter to invoke that very same judgment to prevent his prosecution for bigamy. He cannot have his cake and eat it too. Otherwise, all that an adventurous bigamist has to do is disregard Article 40 of the Family Code, contract a subsequent marriage and escape a bigamy charge by simply claiming that the first marriage is void and the subsequent marriage is

equally void for lack of a prior judicial declaration of nullity of the first. A party may even enter into a marriage aware of the absence of a requisiteusually the marriage licenseand thereafter contract a subsequent marriage without obtaining a declaration of nullity of the first on the assumption that the first marriage is void. Such scenario would render nugatory the provisions on bigamy. As succinctly held in Landicho v. Relova, 22 SCRA 731(1968): Parties to a marriage should not be permitted to judge for themselves its nullity, [as] only competent courts have such authority. Prior to such declaration of nullity of the first marriage is beyond question. A party who contracts a second marriage then assumes the risk of being prosecuted for bigamy. A prejudicial question does not conclusively resolve the guilt or innocence of the accused but simply tests the sufficiency of the allegations in the information in order to sustain the further prosecution of the criminal case. A party who raises a prejudicial question is deemed to have hypothetically admitted that all the essential elements of a crime have been adequately alleged in the information, considering that the prosecution has not yet presented single evidence on the indictment or may not yet have rested its case. A challenge of the allegations in the information on the ground of prejudicial question is in effect a question on the merits of the criminal charge through a non-criminal suit. Ignorance of the existence of Article 40 of the Family Code cannot be successfully invoked as an excuse. The contracting of a marriage knowing that the requirements of the law have not been complied with or that the marriage is in disregard of a legal impediment is an act penalized by the Revised Penal Code. The legality of a marriage is a matter of law and every person is presumed to know the law. As respondent did not obtain the judicial declaration of nullity when he entered into the second marriage, why should he be allowed to belatedly obtain that judicial declaration in order to delay his criminal prosecution and subsequently defeat it by his own disobedience of the law? If he wants to raise the nullity of the previous marriage, he can do it as a matter of defense when he presents his evidence during the trial proper in the criminal case. The elements of bigamy are (1) the offender has been legally married; (2) that the first marriage has not been legally dissolved, or in case his or her spouse is absent, the absent spouse has not been judicially declared presumptively dead; (3) that he contracts a subsequent marriage; and (4) the subsequent marriage would have been valid had it not been for the existence of the first. The exceptions to prosecution for bigamy are those covered by Article 41 of the Family Code and by PD 1083 otherwise known as the Code of Muslim Personal Laws.

Lucio Morigo v People (2002) FACTS: Lucio Morigo and Lucia Barrete were boardmates. After school year 1977-78 they lost contact with each other. In 1984, Lucio Morigo was surprised to receive a card from Lucia Barrete from Singapore. The former replied and after an exchange

of letters, they became sweethearts. In 1986, Lucia returned to the Philippines but left again for Canada to work there. While in Canada, they maintained constant communication. In 1990, Lucia came back to thePhilippines and proposed to Lucio to join her inCan ada. Both agreed to get married. On September 8,1990, Lucia reported back to her work in Canada leaving appellant Lucio behind. On August 19, 1991,Lucia filed with the Ontario Court for divorce which was granted on January 17, 1992. On October 4, 1992,appellant Lucio Morigo married Maria Jececha Lumbago. On September 21, 1993, accused filed acomplaint for judicial declaration of nullity of marriage in the RTC. On October 19, 1993, Lucio was chargedwith Bigamy and found guilty thereon. HELD: The primordial issue should be whetheror not petitioner committed bigamy and if so, whetherhis defense of good faith is valid. In Marbella-Bobis v.Bobis, we laid down the elements of bigamy thus:(1)the offender has been legallymarried;(2)the first marriage has not beenlegally dissolved, or in case his or her spouseis absent, the absent spouse has not been judicially declared presumptively dead;(3)he contracts a subsequent marriage; and (4)the subsequent marriage would have been valid had it not been for the existence of the first. Applying the foregoing test to the instant case, we note that the trial court found that there was no actual marriage ceremony performed between Lucio and Lucia by a solemnizing officer. Instead, what transpired was a mere signing of the marriage contract by the two, without the presence of a solemnizingofficer.The first element of bigamy as a crime requires that the accused must have been legally married. But in this case, legally speaking, the petitioner was never married to Lucia Barrete. Thus,there is no first marriage to speak of. Under theprinciple of retroactivity of a marriage being declared void ab initio, the two were never married from the beginning. The contract of marriage is null; it bears no legal effect. Taking this argument to its logical conclusion, for legal purposes,petitioner was not married to Lucia at the time he contracted the marriage with Maria Jececha. The existence and the validity of the first marriage being an essential elementof the crime of bigamy, it is but logical that a conviction for said offense cannot be sustained wherethere is no first marriage to speak of. The petitioner,must, perforce be acquitted of the instant charge. Salvador Abunado et al. V. People of the Philippines G.R. No. 159218, 30 March 2004, The outcome of the civil case for annulment of petitioners marriage to Narcisa had no hearing upon the determination of petitioners innocence or guilt in the criminal case for bigamy, because all that is required fro the charge of bigamy to prosper is that the first marriage be subsisting at the time the second marriage is contracted.Thus, under the law, a marriage even one which is void or voidable, shall be deemed valid until declared otherwise in a judicial proceeding. In this case, even if petitioner eventually obtained a declaration that his first marriage was void ab ignition, the point is, both the first and the second marriage were subsisting before the first marriage was annulled. Salvador Abunado married Zenaida Bias on December 24, 1955. In 1966, Salvador separated from Zenaida. On September 18, 1967, Salvador married Narcisa Arcea. Several years later in 1988,

Narcisa left the country to work in Japan. On January 10, 1989, Salvador contracted a second marriage with Zenaida. When Narcisa returned in 1992, she discovered that Salvador left their conjugal home and now has an extramarital affair with a certain Fe Corazon Palto. Narcisa also learned of Salvadors marriage to Zenaida in1989. On January 19, 1995, Salvador filed an annulment case against Narcisa. That same year, on May 18,1995, Narcisa filed a complaint for bigamy against Salvador and Zenaida. Salvador, however, claimed hecannot be liable for bigamy since Narcisa has consented to his marriage with Zenaida. Salvador moreover, argued that his petition for annulment was a prejudicial question hence, proceedings in the bigamy case should first be suspended to give way to the civil case for annulment. ISSUE: Whether or not the subsequent judicial declaration of the nullity of the first marriage was immaterial to the case HELD: First Issue: Subsequent Judicial Declaration Of the Nullity Of the First Marriage Was Immaterial Salvador cannot invoke the benefit of a prejudicial question nor the order of the trial court annulling his marriage with Narcisa since the offense had already been consummated even before he instituted the civil case for annulment which preceded Narcisas complaint for bigamy. A prejudicial question has been defined as one based on a fact distinct and separate from the crime but so intimately connected with it that it determines the guilt or innocence of the accused, and for it to suspend the criminal action, it must appear not only that said case involves facts intimately related to those upon which the criminal prosecution would be based but also that in the resolution of the issue or issues raised in the civil case, the guilt or innocence of the accused would necessarily be determined. The rationale behind the principle of suspending a criminal case in view of a prejudicial question is to avoid two conflicting decisions. The subsequent judicial declaration of the nullity of the first marriage was immaterial because prior to the declaration of nullity, the crime had already been consummated. Moreover, petitioners assertion would only delay the prosecution of bigamy cases considering that an accused could simply file a petition to declare his previous marriage void and invoke the pendency of that action as a prejudicial question in the criminal case. We cannot allow that. The outcome of the civil case for annulment of petitioners marriage to Narcisa had no bearing upon the determination of petitioners innocence or guilt in the criminal case for bigamy, because all that isrequired for the charge of bigamy to prosper is that the first marriage be subsisting at the time the second marriage is contracted. Thus, under the law, a marriage, even one which is void or voidable, shall be deemed valid until

declared otherwise in a judicial proceeding. In this case, even if petitioner eventually obtained a declaration that his first marriage was void ab initio, the point is, both the first and the second marriage were subsisting before the first marriage was annulled. Salvadors conviction is affirmed.

Lapuz-Sy vs. Eufemio43 SCRA 177 Facts:Carmen Lapuz-Sy filed a petition for legal separation against Eufemio, married civilly on September 21,1934 and canonically on September 30, 1943. In 1943, her husband abandoned her. Carmen discovered Eufemio cohabiting with a Chinese woman, Go Hiok. Carmen prayed for the issuance of the decree of legal separation.Eufemio amended answer to the petition and alleged affirmative.Before the trial could be completed, petitioner died in a vehicular accident. With these respondentmoved to dismiss the petition for legal separation on two grounds; the petition was filed beyond 1-year periodand the death of petitioner abated the acted for legal separation. Issue:Whether or not the death of plaintiff in action for legal separation before final decree abated the action. Ruling:An action for legal separation which involves nothing more than the bed-and-board separation of thespouses is purely personal. The Civil Code of the Philippines recognizes this in its Article 100, by allowing onlythe innocent spouse and no one else to claim legal separation; and in its Article 108, by providing that thespouses can, by their reconciliation, stop or abate the proceedings and even rescind a decree of legal separationalready rendered. Being personal in character, it follows that the death of one party to the action causes the deathof the action itself actio personalis moritur cum persona Laperal vs. Republic GR No. 18008, October 30, 1962 FACTS: The petitioner, a bona fide resident of Baguio City, was married with Mr. Enrique R. Santamaria on March 1939. However, a decree of legal separation was later on issued to the spouses. Aside from that, she ceased to live with Enrique. During their marriage, she naturally uses Elisea L. Santamaria. She filed this petition to be permitted to resume in using her maiden name Elisea Laperal. This was opposed by the City Attorney of Baguio on the ground that it violates Art. 372 of the Civil Code. She was claiming that continuing to use her married name would give rise to confusion in her finances and the eventual liquidation of the conjugal assets. ISSUE: Whether Rule 103 which refers to change of name in general will prevail over the specific provision of Art. 372 of the Civil Code with regard to married woman legally separated from his husband.

HELD: In legal separation, the married status is unaffected by the separation, there being no severance of the vinculum. The finding that petitioners continued use of her husband surname may cause undue confusion in her finances was without basis. It must be considered that the issuance of the decree of legal separation in 1958, necessitate that the conjugal partnership between her and Enrique had automatically been dissolved and liquidated. Hence, there could be no more occasion for an eventual liquidation of the conjugal assets. Furthermore, applying Rule 103 is not a sufficient ground to justify a change of the name of Elisea for to hold otherwise would be to provide for an easy circumvention of the mandatory provision of Art. 372. Petition was dismissed.

Republic of the Philippines vs Jose A. Dayot GR No. 175581 March 28, 2008 Fact of the Case: On November 24, 1986 Jose and Felisa Dayot were married at the Pasay City Hall. In lieu of a marriage license, they executed a sworn affidavit attesting that both ofthem are legally capacitated and that they cohabited for atleast five years when in factthey only barely known each other since February 1986.On 1993, Jose filed a complaintfor Annulment and/or Declaration of Nullity of Marriage contending that their marriagewas sham, as to no ceremony was celebrated between them; that he did not execute thesworn statement that he and Felisa had cohabited for atleast five years; and that hisconsent was secured through fraud. His sister, however, testified as witness that Josevoluntarily gave his consent during their marriage. The complaint was dismissed onRegional Trial Court stating that Jose is deemed estopped from assailing the legality ofhis marriage for lack of marriage license. It is claimed that Jose and Felisa had lived together from 1986 to 1990, and that it took Jose seven years before he sought thedeclaration of nullity; The RTC ruled that Joses action had prescribe. It cited Art 87 ofthe New Civil Code which requires that the action for annulment must be commenced bythe injured party within four years after the discovery of fraud. Jose appealed to the Courtof Appeals which rendered a decision declaring their marriage void ab initio for absenceof marriage license. Felisa sought a petition for review praying that the Court of AppealsAmended decision be reversed and set aside. Issue: (1) Whether the falsity of an affidavit of marital cohabitation, where the partieshave in truth fallen short of the minimum five-year requirement., effectivelyrenders the marriage voib an initio for lack of marriage. (2) Whether or not the action for nullity prescribes as the case here where Jose

filed a complaint after seven years from contracting marriage. Held: (1)Yes.The intendment of law or fact leans towards the validity of marriage, willnot salvage the parties marriage, and extricate them from the effect of a violation of thelaw. The Court protects the fabric of the institution of marriage and at the same time waryof deceptive schemes that violate the legal measures set forth in the law. The case cannotfall under irregularity of the marriage license, what happens here is an absence ofmarriage license which makes their marriage void for lack of one of the essentialrequirement of a valid marriage. (2) No. An action for nullity is imprescriptible. Jose and Felisas marriage wascelebrated san a marriage license. The right to impugn a void marriage does not prescribe. People vs. Schneckenburger FACTS:

Accused Rodolfo A. Schneckenburger married the complainant Elena Ramirez Cartagena and after seven years of marital life, they enter into an agreement, for reason of alleged incompatibility of character, to live separately from each other. The accused, without leaving the philippines, secured a decree of divorce from Mexico. Because of the nullity of the divorce decreed by the Mexico Court, complainant herein instituted two actions against the accused, one for bigamy in CFI Rizal and the other for concubinage in CFI Manila. The first culminated in the conviction of the accused. ISSUE: W/N the accused should be liable for concubinage HELD: No. The document executed by and between the accused and the complainant in which they agreed to be en completa libertad de accion en cualquier acto y en todos conceptos, (wala na kaya sa akong spanish capacity), while illegal for the purpose for which it was executed, constitutes nevertheless a valid consent to the act of concubinage within the meaning of sec. 344 of RPC. There can be no doubt that by such agreement, each party clearly intended to forego the illicit acts of the other.

People v. Sansano and Ramos Facts: Ursula Sensano and Mariano Venturawere married on April 29, 1919. Afterthe birth of their only child, th ehusband left his wife and was gone for three years without writing to her or sending her support. While thehusband was away, the wife began tolive with Marcelo Ramos. When husband returned, he filed a charge of adultery which resulted in a conviction and a sentencing. When the sentence was completed, wife begged the husband to take her back but herefused. Abandoned a second time, the wife fled back to Ramos. Husband,knowing that his wife reverted to her lover, did

not do anything to asserts his rights and left for the states. He returned to the Philippines seven years later and presented a second charge of adultery. Issue: WON the second charge of adulterycan be a ground for legal separation. Held/Ratio: No. The husband was only assuming a mere pose of an offended spouse.He consented to the adulterous relations of his wife and Ramos and is thus, therefore barred from instituting any criminal proceeding. Even if he was still in a foreign country, he would have still been able to take action against the accused but since he didnt take this option, it showed a considerable lack of genuine interest as the offended party Benedicto v. De La Rama, the Supreme Court denied a petition for divorce filed by plaintiff-wife due to the adultery of the defendant-husband upon finding, from its review of the factual basis of the trial court, that the plaintiff was also guilty of adultery. The Court stated that even the allegation by the wife of condonation by the husband would not have the far-reaching effect to entitle her to a divorce against him in a case like the present one. In short, the previous adultery by the wife, even if condoned, forever bars her from seeking a divorce on ground of adultery committed later by the husband because there is no law which covers the situation to resolve this immoral impasse! William H. Brown vs. Juanita Yambao Facts: 1.While Brown was interned from 1942 to 1945 at UST, Yambao committed adultery with Carlos Field of whom she had a baby girl. 2.Brown learned of this upon his release from internment in 1945, since then they lived separately. They later executed a document liquidating their conjugal partnership and assigning properties as share of Yambao. 3.Brown lived with another woman and had begotten children. 4.The CFI denied legal separation due to Browns incurring of misconduct of similar nature that barred his right of action Issue: 1.Did the assistant fiscal erred in it acted as counsel for the defaulting wife? 2.Was the husband barred from his right of action, of legal separation, due to incurring of misconductof similar nature and prescription?

Ratio:1.It was legitimate for the fiscal to bring to light any circumstances that could give rise to theinference that the wifes default was calculated, or agreed upon, to enable appellant to obtain thedecree of legal separation that he sought without regard to the legal merits of his case. One suchcircumstance is obviously the fact that Browns cohabitation with a woman other than his wife,since it bars him from claiming legal separation by Art 100 CC.Art 100 CC - Where both spouses are offenders, a legal separation cannot be claimed by either of them. Collusion between the parties to obtain legal separation shall cause the dismissal of the petition. The calling for intervention of the state attorneys in case of uncontested proceedings for legalseparation is to emphasize that marriage is more than a mere contract; that it is a social institution inwhich the state is vitally interested, so that its continuation or interruption can not be made to dependupon the parties themselves. 2.Browns action was already barred because he did not file for petition for legal separationproceeding until 10 years after he learned of his wifes adultery. Browns inaction for 10 years alsoevidences condonation or connivance on his part.Art 102 CC- An action for legal separation cannot be filed except within one year from and after thedate on which the plaintiff became cognizant of the cause and within 5 years from and after the datewhen such cause occurred. Socorro Matubis, plaintiff and appellant vs. Zoilo Praxedes, defendant and appelleeOctober 25, 1960/ Appeal from a judgment of the CFI of Camarines Sur/ Surtida, J. Facts: 1.January 10, 1943, Matubis and Praxedes were married 2.May 30, 1944, the couple agreed to live separately, which status remained unchanged until thepresent 3.April 3, 1948, the couple entered into an agreement a.Both relinquish their right over the other as legal husband and wife b.Both are free to get any mate and live with as husband and wife without any interference by any of them, nor either of them can prosecute the other for adultery or concubinage or anyother crime or suit arising from their separation. The wife is no longer entitled for any support from the husband or any benefits he mayreceive thereafter, no is the husband entitled for anything from the wifed.Neither of them can claim anything from the other from the time they verbally separated,May 30, 1944 to the present when they made their verbal separation into writing. 4.January 1955, Praxedes began cohabiting with Asuncion Rebulado. 5.Matubis filed complaint on April 24, 1956. 6.CFI dismissed complaint due to condonation.

Issue: Was the agreement of both parties constituted condonation which bar the wife from right of action? Held: The CFI decision is affirmed.Ratio: Counsel in his brief submits that the agreement is divided into 2 parts. The 1st part having to dowith the act of living separately which he claims to be legal, and the 2nd partthat which becomes alicense to commit the ground for legal separation, which is admittedly illegal. The court does not share theappellants view. Condonation and consent here are not only implied but expressed. Art 100 CC providesthat legal separation may be claimed only by the innocent spouse, provided there has been nocondonation of or consent to the adultery or concubinage. Having condoned and or consented in writing,the plaintiff is now undeserving of the courts sympathy. Joel Jimenez vs Remedios Caizares Impotency Joel and Remedios are husband and wife. Joel later filed for annulment on grounds that Remedios is impotent because her genitals were too small for copulation and such was already existing at the time of the marriage. Remedios was summoned to answer the complaint of Joel but she refused to do so. It was found that there was no collusion between the parties notwithstanding the noncooperation of Remedios in the case. Remedios was ordered to have herself be submitted to an expert to determine if her genitals are indeed too small for copulation. Remedios again refused to do as ordered. The trial was heard solely on Joels complaint. The marriage was later annulled. ISSUE: Whether or not Remedios impotency has been established. HELD: In the case at bar, the annulment of the marriage in question was decreed upon the sole testimony of Joel who was expected to give testimony tending or aiming at securing the annulment of his marriage he sought and seeks. Whether Remedios is really impotent cannot be deemed to have been satisfactorily established, because from the commencement of the proceedings until the entry of the decree she had abstained from taking part therein. Although her refusal to be examined or failure to appear in court show indifference on her part, yet from such attitude the presumption arising out of the suppression of evidence could not arise or be inferred, because women of this country are by nature coy, bashful and shy and would not submit to a physical examination unless compelled to by competent authority. Impotency being an abnormal condition should not be presumed. The presumption is in favor of potency. The lone testimony of Joel that his wife is physically incapable of sexual intercourse is insufficient to tear asunder the ties that have bound them together as husband and wife. LACSON V. SAN JOSE-LACSON August 30, 1968 Under Article 136 (Voluntary Separation of Property)Digest by Apesa Chungalao Three consolidated cases: Alfonso Lacson v. Carmen San-Jose Lacson and the Court of Appeals (L-23482)Carmen San-Jose Lacson v. Alfonso Lacson (L-23767)Alfonso Lacson v. Carmen San Jose-LacsonBackground:Alfonso

and Carmen were married on February 14, 1953. They had four children. On January 9,1963 Carmen left the conjugal home in Bacolod and resided in Manila. On March 12, 1963 she filed acomplaint in the Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court (JDRC) for custody of all their children as wellas support for them and herself. However, through the assistance of their respective lawyers, the spousesreached an amicable settlement as to custody of the kids, support, and separation of property. On April27, 1963, they filed a joint petition with the CFI of Negros Occidental, submitting that they had mutuallyagreed upon the dissolution of their conjugal partnership. The terms included a) separation of property, b)all earnings of each spouse shall belong to that spouse exclusively, c) the custody of the two elder children shall be awarded to Alfonso and the two younger children to Carmen, d) Alfonso shall payCarmen a monthly allowance of P200.00 for the support of the children, and e) each petitioner shall havereciprocal rights of visitation and every summer the former spouses shall swap [my word] kids. For that particular year, however, Carmen was allowed custody of all four children until June of 1963, when shewas supposed to return the two older children to Alfonsos custody.Finding the foregoing joint petition as conformable to the law, the CFI issued an order approvingtheir compromise agreement on the very same day. On May 7, however, Carmen filed a motion with theJDRC alleging that the compromise agreement was the only way she could get custody of all the childrenand praying that she be relieved of the agreement pertaining to the custody and visitation of the childrenand that she now be awarded full custody [bitch]. Naturally, Alfonso opposed the motion and the JDRCruled in his favour. Carmen went to the Court of Appeals and the CA certified the case to the SupremeCourt. Carmen went to the CFI and filed a motion for reconsideration, basically claiming the same thing.Alfonso opposed. The CFI favored Alfonso and ordered Carmen to return the two older children by June,on pain of contempt. It is from this decision that the instant case springs. Carmen instituted certiorari proceedings with the CA against the CFI, saying the CFI committed grave abuse of discretion and actedin excess of jurisdiction in ordering the immediate execution of the compromise agreement. The CAdeclared void the portion of the agreement pertaining to the custody of children. Issue/Held/Ratio: Was the assailed compromise agreementand the judgment of the CFI grounded on said agreement conformable to law? YESbut only as far as the separation of property of spouses and the dissolution of the conjugal partnership, in accordance with Article 191 of the Civil Code. The spouses did not appear tohave any creditors who would have been prejudiced by their arrangement. At the time of the decision thespouses had been separated five years and so the propriety of severing their financial and proprietary interests was manifest. (However, the Court maintained that approving the separation of property and dissolution of conjugal partnership did not amount to recognition or legalization of de facto separation.)As to the custody of the children, they were all below 7 years of age at the time of the agreement and sothe CA was correct in awarding the custody to the mother. The Court was also loath to uphold the couples agreement regarding the custody of the children, citing rights of the children to proper care not anchored on the solely on the whims of his or her parents. Courts must decide fitness of parents for custody. REYES VS. INES-LUCIANO

Facts:Manuel Reyes attacked his wife twice with the intent to kill. A complaint was filed on June 3, 1976: the first attempton March was prevented by her father and the second attempt, where in she was already living separately from her husband, was stopped only because of her drivers intervention. She filed forlegal separation on that ground and prayed for support pendente lite for herself and her three children. Thehusband opposed the application for support on the ground that the wife committed adultery with her physician. The respondent Judge Ines-Luciano of the lower court granted the wife pendente lite. The husband filed amotion for reconsideration reiterating that his wife is not entitled to receive such support during the pendency of the case, and that even if she is entitled to it, the amount awarded was excessive. The judge reduced the amount from P5000 to P4000 monthly.Husband filed a petition for certiorari in the CA to annul the order grantingalimony. CA dismissed the petitionwhich made the husband appeal to theSC. Issue: WON adultery of the wife was a defense in an action for support. WONsupport can be administered duringthe pendency of an action. Held/Ratio: Yes provided that adultery is established by competent evidence.Mere allegations will not bar her right to receive support pendente lite.Support can be administered duringthe pendency of such cases. In determining the amount, it is notnecessary to go into the merits of the case. It is enough that the facts be established by affidavits or other documentary evidence appearing in the record. [The SC on July, 1978ordered the alimony to beP1000/month from the period of Juneto February 1979, after the trial, it wasreverted to P4000/month based on theaccepted findings of the trial court that the husband could afford it because of his affluence and because it wasntexcessive.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Marbella-Bobis V BobisDocument3 paginiMarbella-Bobis V BobisMaverick Jann EstebanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest (Legal Research)Document6 paginiCase Digest (Legal Research)Dael GerongÎncă nu există evaluări

- IMELDA MARBELLA BOBIS vs. ISAGANI D. BOBISDocument4 paginiIMELDA MARBELLA BOBIS vs. ISAGANI D. BOBISAlleoh AndresÎncă nu există evaluări

- GR No. 138509Document3 paginiGR No. 138509Nathan Dioso PeraltaÎncă nu există evaluări

- IMELDA MARBELLA-BOBIS, Petitioner, vs. ISAGANI D. BOBIS, RespondentDocument10 paginiIMELDA MARBELLA-BOBIS, Petitioner, vs. ISAGANI D. BOBIS, RespondentAM CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bobis V BobisDocument7 paginiBobis V BobisEric Frazad MagsinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marbella-Bobis V BobisDocument5 paginiMarbella-Bobis V BobisakosivansotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest Marbella-Bobis V. BobisDocument3 paginiCase Digest Marbella-Bobis V. BobisJc IsidroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capili V. People G.R. No. 183805 July 3, 2013 FactsDocument7 paginiCapili V. People G.R. No. 183805 July 3, 2013 FactsMirellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Montanez V CiprianoDocument3 paginiMontanez V CiprianoAsaiah Windsor100% (1)

- Domingo v. Court of Appeals FactsDocument11 paginiDomingo v. Court of Appeals FactsRJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morigo V PeopleDocument2 paginiMorigo V Peopletherouguedragonrider14Încă nu există evaluări

- Bobis VS BobisDocument4 paginiBobis VS BobisencinajarianjayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morigo Vs People G.R. No. 145226Document3 paginiMorigo Vs People G.R. No. 145226Levi Isalos100% (1)

- PERSONS Article 36 Morigo vs. People: Te vs. Court of AppealsDocument5 paginiPERSONS Article 36 Morigo vs. People: Te vs. Court of AppealsCarlota Nicolas VillaromanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wiegel vs. Sempio-Dy 143 SCRA 449: Farinas Civrev Case Digests 3 - 1Document18 paginiWiegel vs. Sempio-Dy 143 SCRA 449: Farinas Civrev Case Digests 3 - 1johnmiggyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest PFR (Groupings)Document4 paginiCase Digest PFR (Groupings)OCP Santiago City100% (1)

- (G.R. No. 138509, July 31, 2000) Imelda Marbella-Bobis, Petitioner, vs. Isagani D. Bobis, RespondentDocument5 pagini(G.R. No. 138509, July 31, 2000) Imelda Marbella-Bobis, Petitioner, vs. Isagani D. Bobis, Respondentkai lumagueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morigo Vs PeopleDocument2 paginiMorigo Vs PeopleBea DiloyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marbella-Bobis V BobisDocument4 paginiMarbella-Bobis V BobisbebdragonÎncă nu există evaluări

- May The Heirs of A Deceased Person File A Petition For The Declaration of Nullity of His Marriage After His Death?Document5 paginiMay The Heirs of A Deceased Person File A Petition For The Declaration of Nullity of His Marriage After His Death?Catherine Cruz GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bayot Vs BayotDocument2 paginiBayot Vs BayotPaolo MendioroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case 86 DOMINGO VS CA OnwardsDocument42 paginiCase 86 DOMINGO VS CA OnwardsMichael DonascoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil 1Document4 paginiCivil 1art_reinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest of Bigamy CasesDocument15 paginiCase Digest of Bigamy CasesAmelyn Albitos-Ylagan Mote100% (1)

- PERSONS - Cases Part 8 (Bobis-Ancheta)Document119 paginiPERSONS - Cases Part 8 (Bobis-Ancheta)Nurlailah AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 54.1 Bobis vs. Bobis DigestDocument2 pagini54.1 Bobis vs. Bobis DigestEstel TabumfamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bobis v. Bobis G.R. No. 138509Document4 paginiBobis v. Bobis G.R. No. 138509salemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morigo Vs PeopleDocument3 paginiMorigo Vs PeopleshiejingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Te v. Choa (Te v. CA) : Persons and Family RelationsDocument5 paginiTe v. Choa (Te v. CA) : Persons and Family RelationsGlorious El DomineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Number: 9 TITLE: Juan Miciano V Andre Brimo CITATION: GR No.22595, November 1, 1927 - 50 Phil 867 FactsDocument5 paginiCase Number: 9 TITLE: Juan Miciano V Andre Brimo CITATION: GR No.22595, November 1, 1927 - 50 Phil 867 FactsAJ CresmundoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mercado vs. TanDocument2 paginiMercado vs. TanShishi Cruz De Leon100% (2)

- U. Lucio Morigo v. PeopleDocument2 paginiU. Lucio Morigo v. PeopleKim ArizalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cueto Vs JimenezDocument5 paginiCueto Vs JimenezClark Vincent PonlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morigo Vs People of The Philippines Case DigestDocument4 paginiMorigo Vs People of The Philippines Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs AragonDocument4 paginiPeople Vs AragonEzekiel Japhet Cedillo EsguerraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rep V Orbecido and Mercado V Tan CDDocument3 paginiRep V Orbecido and Mercado V Tan CDaiceljoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Bobis V BobisDocument2 pagini3 Bobis V BobisCai CarpioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bobis Vs BobisDocument3 paginiBobis Vs BobisHazel Grace AbenesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases Full Text Bobis To AnchetaDocument71 paginiCases Full Text Bobis To AnchetaBimby Ali LimpaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morigo y Cacho vs. People of The PhilippinesDocument34 paginiMorigo y Cacho vs. People of The PhilippinesBannylyn Mae Silaroy GamitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Domingo To CarinoDocument14 paginiDomingo To CarinoCha GalangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Additional Cases FC 35-48Document7 paginiAdditional Cases FC 35-48Bimby Ali LimpaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest Sept 12Document9 paginiCase Digest Sept 12Camille Anne DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bobis V Bobis Case DigestDocument2 paginiBobis V Bobis Case DigestARÎncă nu există evaluări

- Void and Voidable MarriagesDocument6 paginiVoid and Voidable MarriagesPiayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toto. Costs Against The PetitionerDocument8 paginiToto. Costs Against The PetitionerAce MarjorieÎncă nu există evaluări

- EDUARDO P. MANUEL, Petitioner, People of The Philippines, RespondentDocument3 paginiEDUARDO P. MANUEL, Petitioner, People of The Philippines, RespondentRoyce Ann PedemonteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest (Bigamous Marriage)Document12 paginiCase Digest (Bigamous Marriage)Djøn AmocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art. 40-42 Case DigestsDocument11 paginiArt. 40-42 Case DigestsnayhrbÎncă nu există evaluări

- TITLE TWELVE: Crimes Against Civil Status of Persons Manuel vs. People (G.R. No. 165842, November 29, 2005)Document8 paginiTITLE TWELVE: Crimes Against Civil Status of Persons Manuel vs. People (G.R. No. 165842, November 29, 2005)Ronnie RimandoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abunado v. PeopleDocument3 paginiAbunado v. PeopleJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Title 12 - Civil StatusDocument4 paginiTitle 12 - Civil StatusSuiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marbella-Bobis Vs Bobis - GR No. 138509Document2 paginiMarbella-Bobis Vs Bobis - GR No. 138509Nikay SerdeñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MARBELLA-BOBIS Vs BOBIS - GR NO. 138509Document2 paginiMARBELLA-BOBIS Vs BOBIS - GR NO. 138509Nikay SerdeñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Synthesis: BIGAMYDocument7 paginiCase Synthesis: BIGAMYRegina Via G. GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bar Review Companion: Civil Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #1De la EverandBar Review Companion: Civil Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #1Încă nu există evaluări

- Sample Motion to Vacate, Motion to Dismiss, Affidavits, Notice of Objection, and Notice of Intent to File ClaimDe la EverandSample Motion to Vacate, Motion to Dismiss, Affidavits, Notice of Objection, and Notice of Intent to File ClaimEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (21)

- Timeless Wisdom - Robin SharmaDocument63 paginiTimeless Wisdom - Robin Sharmasarojkrsingh100% (17)

- Legal Implications of Cold Chain ManagementDocument19 paginiLegal Implications of Cold Chain ManagementJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- ElectioneeringDocument1 paginăElectioneeringJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Timeless Wisdom - Robin SharmaDocument63 paginiTimeless Wisdom - Robin Sharmasarojkrsingh100% (17)

- Timeless Wisdom - Robin SharmaDocument63 paginiTimeless Wisdom - Robin Sharmasarojkrsingh100% (17)

- Protecting People From Tobacco SmokeDocument32 paginiProtecting People From Tobacco SmokeJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Development of The Manual of Local Reform CoordinationDocument134 paginiDevelopment of The Manual of Local Reform CoordinationJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines Sub-Allotment MalariaDocument24 paginiGuidelines Sub-Allotment MalariaJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sexual Harassment What Can Be DoneDocument20 paginiSexual Harassment What Can Be DoneJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sexual Harassment What Can Be DoneDocument20 paginiSexual Harassment What Can Be DoneJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of Civil StatusDocument1 paginăAffidavit of Civil StatusJaidee Sanchez100% (1)

- BFP SOPonFireandArsonInvestigationDocument9 paginiBFP SOPonFireandArsonInvestigationhailglee192571% (7)

- Brief History of Tiki Beach ResortDocument21 paginiBrief History of Tiki Beach ResortJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- !!! Worksheet This Week-Fillable PDFDocument1 pagină!!! Worksheet This Week-Fillable PDFzupervioletaÎncă nu există evaluări

- QOPMDocument2 paginiQOPMJaidee Sanchez100% (1)

- Crimes Against National SecurityDocument1 paginăCrimes Against National SecurityJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRIM LAW REVIEW. Case Doctrines - MidtermsDocument21 paginiCRIM LAW REVIEW. Case Doctrines - Midtermsolaydyosa100% (8)

- CONFLICTS Salonga Book DigestDocument84 paginiCONFLICTS Salonga Book Digestcgmeneses95% (20)

- 2013 August Printable Calendar ColorDocument1 pagină2013 August Printable Calendar ColorJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRIM LAW REVIEW. Case Doctrines - MidtermsDocument21 paginiCRIM LAW REVIEW. Case Doctrines - Midtermsolaydyosa100% (8)

- Republic of TheDocument2 paginiRepublic of TheJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abunado v. PeopleDocument3 paginiAbunado v. PeopleJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Special Civil ActionsDocument2 paginiSpecial Civil ActionsJaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- LIVELOUD Chord PatternsDocument5 paginiLIVELOUD Chord PatternsTey Castillo100% (1)

- DECS Form 137Document2 paginiDECS Form 137Jaidee SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carino V Carino Digest 1Document2 paginiCarino V Carino Digest 1Onireblabas Yor OsicranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sections 21-3 Under Indian Divorce ActDocument16 paginiSections 21-3 Under Indian Divorce Actkhadija khanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statutory Declaration For Single Status LettersDocument2 paginiStatutory Declaration For Single Status LettersSolomon AbrahamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Read The Following Birth Announcement. Then Answer The Questions Below ItDocument6 paginiRead The Following Birth Announcement. Then Answer The Questions Below ItMarius MikelionisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wedding ScriptDocument1 paginăWedding ScriptPolibert T. Fuentes Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Team Code - : in The Matter ofDocument20 paginiTeam Code - : in The Matter ofSheela AravindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases SummaryDocument52 paginiCases SummaryROSASENIA “ROSASENIA, Sweet Angela” Sweet AngelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Second Motion Neetu VS VickyDocument31 paginiSecond Motion Neetu VS VickyRimika Chauhan100% (1)

- Misi Penyelamatan Diri: Dinamika Psikologis Rasa Malu Pasangan (Istri) KoruptorDocument21 paginiMisi Penyelamatan Diri: Dinamika Psikologis Rasa Malu Pasangan (Istri) KoruptorErvi WulandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961Document25 paginiDowry Prohibition Act, 1961nupurÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Jumawan Case DigestDocument2 paginiPeople Vs Jumawan Case DigestThea Porras100% (2)

- Stavros NiarchosDocument20 paginiStavros NiarchosPatsy StoneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Argumentative Essay Arranged Marriages - No Counter (Sarath)Document2 paginiArgumentative Essay Arranged Marriages - No Counter (Sarath)Doung PichchanbosbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sonnet 116 - William ShakespeareDocument11 paginiSonnet 116 - William ShakespeareswapnochandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Molina DoctrineDocument30 paginiMolina DoctrineApril Charm ObialÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Corinthians 7Document25 pagini1 Corinthians 7Gino RicafortÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aunt Jennifer's TigersDocument17 paginiAunt Jennifer's TigersHigreeve SrudhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Attestation Fee ListDocument2 paginiAttestation Fee ListNithin KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suntay vs. Cojuangco-Suntay (October 2012)Document2 paginiSuntay vs. Cojuangco-Suntay (October 2012)zaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relax and Rejoice A Marriage Manual Vol.2Document176 paginiRelax and Rejoice A Marriage Manual Vol.2Harmanjot Kaur100% (1)

- SURNAMES Study Guide Answered in BlueDocument6 paginiSURNAMES Study Guide Answered in BlueJani Misterio100% (2)

- DIVORCE Sociology AssignmentDocument18 paginiDIVORCE Sociology AssignmentkeirenmavimbelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Right To Privacy Vis-A-Vis Matrimonial Rights in India: An Analysis of Judicial ApproachDocument11 paginiRight To Privacy Vis-A-Vis Matrimonial Rights in India: An Analysis of Judicial ApproachRahul TambiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amended Formal Offer of ExhibitsDocument4 paginiAmended Formal Offer of ExhibitsSalva MariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ting V Velez-TingDocument3 paginiTing V Velez-TingCamille TapecÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enemy Boss - The Same Old LoveDocument2 paginiEnemy Boss - The Same Old LoveKD StrokerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fac. Milton CamposDocument235 paginiFac. Milton CamposTalita GabrielaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Johansen v. Civil Registrar (2021)Document1 paginăJohansen v. Civil Registrar (2021)Juan Angel EvangelistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Courtship That Glorifies GodDocument9 paginiCourtship That Glorifies GodNne EkehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mutual Divorce 1st MotionDocument23 paginiMutual Divorce 1st Motionsakshi mehtaÎncă nu există evaluări