Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Military Review Aug 1947

Încărcat de

CAP History LibraryTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Military Review Aug 1947

Încărcat de

CAP History LibraryDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

....

VOLUME XXVII

North American Bditiort

LT COL D. L. DURFEE

LT COl, M. N. SQUIRES'

AUGUST 1947 NUMBER 5

Editor in Chief

'COl.ONEL R. A. NADAL

Editors

S]JewiNh-.4merican Edit jon Brazilian Edition

LT COL .R. < GIMENEZ-DE LA ROSA CAPT PAnUA, Rraziliull Army

MAJ R. A. SANDIN

Editorial Assistants

LT H. CORDERO, LT J.

Administration

Acl1nillistratit'c OjJicer: MAJ D. Lo" NmmYKE

Production 'Alauagl'r: MAJ A. T. SNELL

CONTENTS

I. '

S,TR.ATEGIC Am. ____ t_---------- ______ _______________________Gen. G. C. Kenney. USA

COl'ttl'tlUNITY RELATIONS AND 1lIlE AR;\lY ADVISORY COi'tlMITTEE:::L _____ .o ___ .: _____Col. G. 'V. Miller, FA

TIlE 2d AR;}toRED DIVISION IN) OPERATION .. CORUA" ______________________Lt. Col. H. M. Exton, FA 11

ESTIMATES OF ENE;\OlY STHENGTH ____________ . _______________________. ______________ Andrew Lossky

20

THEATER REPLACEMENT SY-ST$:\IS OF WORLD WAR II _____________________Lt. Col. C. L. Elver. In!.

26

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODERN ICONVOY SYSTEM __________ Rear Admiral M. B. Browning, USN (Ret.) 35

CO,MMAND RESPONSlUILITY FOR ADEQl1ATE DENTAL SERVICE________________Lt. Col. G. F. Jeffcott, DC , 39

PROC'UHEMENT FOR WAR ______ L______________________________________ ___ Lt" Col. -L. J. Fuller, CE

43

THE OCCUPATION OF KOREA-bpERATlflNS AND ACCOMPLISHil.U:NTS _______ . ___Lt. Col. D. Smclmr. J.' 4 i'l 53

,JOINT OPERATION ASPECTS OFl THE OKINAW-A CAMPAIGN __________________Lt" W. Killilae, G$C

61

MILITARY NOTES AROUND WOHLIJ __________ -- ___ - ___ - _______________________________________ THk _

65

73

l"tIlEIGN T - ==== ===== == == == ===

73

82

88

:::::::::::::: ::: ::::::::::::::::::

91

94

Personnel Selec'tion the British Army-The Other ______________________________

97

104

French Air Forces _________________._______ -- :--------- --- -"---- ---------- 109

__ l ===: = = ==: = ==::

i.

" I

MILITARY REVIEW-Published monthly'by the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan

sas. Entered as second-class matter August 31, 1934. at the Post Office at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; under the

AI!t of March 3, 1897. Subscription rates: $3.00 (U.S. currency) per year for 12 issues. No extra charge for

foreign postage on new or renetal subscriptions. Reprints are authorized, provided credit is given the "MILI

TARY REVIEW." C&GSC, Kansas.

i '

COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE

COMMANDANT

,LIEUTENANT GENERAL L. T. GEROW

ASSISTANT COMMANDANT

MAJOR GENERAL W. F. DEAN

STAFF

COLONEL E. D. POST, General Stalf Co/'pB- ___________________________ Chief of St<lif

COLONEL F. S. MATTHEWS, General Stalf CO)}Js ______________________A. C. of S., G-l

COLONEL P. R. KNIGHT, General Stalf COIps ____________________A. C. of S., G-2, G-3

COLONEL O. C. MOOD, General Stalf Corps________________'____________A. C.'of S., G-4

COLONEL R. B. PATTERSON, Adj. Gen. Dept. _____________"__________ Adjutant General

FACULTY

COLONEL D. H. HUNDLEY, Infantry________________Commandant, School of Personnel

COLONEL H. V. WHITE, Infantry________________Commandant, School of Intelligence

COLONEL R. N. YOUNG, Infantry______________Commandant, School of Combined Arms

COLONEL A. W. PENCE, Corps of Engineers________Commandant, School of Logistics

COLONEL D. C. FAITH, Infantry________ Director, Department of Analysis and Research

COLONEL R. J. BROWNE, Ail' Corps________ , ____________________Director, Air Section

QAPTAIN H. B. TEMPLE, United States Navy______ Naval Section

COLONEL S. R. OSMOND, B1'iti$h Anny____________DiTector, Allied Instructors Section

CQLONEL W. A. CAMPBELL, Field A1,tille1'y________ Director, Extension Courses Section

COLONEL W. H. HENNIG, Coast Artillery CorpB- _________Director, Language Section

COLONEL W., ,J. BAIRD, Infant1y ____ , __ __________ lChief, Instructor Training Section

COLONEL J; 'H.' VAN VLIET, infantl'y___________J _______________._________Secretary

stra}egic Air Command

I '

'[

,

1 General George C: Kenney,

Commandin"g General, Strategic Air Command"

I

I N the of AmJ'ica's great South

\vest, the pattern for nation's concept

of long-range strategic (air power is taking

shape today. It is a !lew design in high

speed flexibility; in a :fresh, air-wise in

terpretation of oldest rule; he

who "gets there with the mostest;"

is he who wins the

As this nation's fi1st line of defense

gears itself into the coming era of trans-,

sonic and supersonicI speeds, the long

range units of Strategic Air Command are

keeping pace with the Iunbelievable devel

opments of the era allready at hand. At

Tucson, Al'izona; Worth, Texas;

,Tampa, Roswell, New Mexico;

Salina, Kansas; Field, Michi

gan;" Manchester, New[ Hampshire; Rapi'd

City, South Dakota; and in Alaska-all

over this country-our Ivery heavy bombers,

and escort fighters engaged in the

most intensive training. in the history of

the' Air Forces. :

Their program is d far cry from the

h;qihazard plan we khew as prepara"tion

Hnd training followingiWorld War 1. Then,

the nearest airdrome i was the pqint for

\\"hich you aimed. a cross-country

llig'ht of a thousand m;iles had all the ear

lllarks of an heroic olleration. Today we

arC not only contin\.lously engaged in'

fljghts of 3,000 or as a routine

lJ aining procedure, bpt, It I write this,

b,'mbei's from our air forces re on )'outine

training flights to E-itrope, to Japan, to.

to the caribb1an.

That program will be continued and it

will be intensified. The farthest bound

aries of American operations abroad will

be regarded by us as simply other air

bases which we can use in our broad pro

gram of orientation, indoctrination and

coordinated operations.

In a nutshell, Strategic Air Command is

striving for three fundamental points as

the basis for its operating policy:

1. The concept of all-weather missions,

not as infrequent test flights, but as day

to-day operations.

2. The concept of absolute and continu

ing flexibility of every element, men and

airplanes and materiel, in every operating

unit.

3. The concept that oc<!ans and land

masses are no longer obstacles; that we

are as surely a weapon of global policy

as any other component 'of national de-_

fense.

Let me elaborate on that policy as we

are effecting it today in all units under

the control of Strategic Ail' Command.'

For twenty years, the development and

advancement of airpower has heen forcibly

attuned to the manifestations of weather.

Cloudy skies meant poor bombing. LO\v

overcast meant closed airdromes. Snow

storms 'meant no take-offs. That era, .r

am happy to report, is gone' forever. Never

again will weather halt, slow or even "inter

fere with the of any bombardment

mission undertaken by, this comman<\. To

keep' our airplanes flying, we have literally

I

4.

,MILITARY REVIEW

demanded "all weat;1er" policy and prac

- -ti,ce from oUI: pilots. They are delivering

and delive,l'ing well.

GCA-Ground Control Approach-guar

antees us landings and take-offs under the

most adverse weathe.' conditions, So-called

-"home airdrome" difficulties are no more.

" Science has stepped in to make what was

missions return because of weathc

er" or aircl;aft-shaking thund.el'heads'. 'No

longer will airplanes be wracked apart by

the terrible power of ;nature's elements

aloft.. With our air-borne radar we see,

the storms miles ahead and determine its'

intensity and centers., By early course

changes, by full knowledge of the depth

B-29s returning from Tokyo in sight of North Field, Guam. (AAF photo.)

impossible yesterday not only possible

but safe today. Andrews Field, Maryland,

and Fort Worth, Texas, were the first two

of our bases to adopt the GCA procedure

as standard for flying operations. Stra

tegic Ail' Coml11and aircraft fly today when

other aircraft are grounded in the Wash

ington-Fort Worth area on account' of

.' weather. We have only begun full-scale

op.el'ations on the immense potential of

fered by GCA. '

. ,Weare constantly perfecting our air

borne radar. No longer will our bomber

and, width of the storm, we can correct

courses to g!!t us to the assigned targets

and to get us there safely.

Finally, we'have our radar bombing: a

technique becoming so nearly per

fect as to challenge the capabilities of the

most skilled bombardier's eyes and the

perfectly operated bomb sight. In

recent mock raids against American cities;

as in our military attacks against Japan

and Germany, the theory of "blind bomb

ing" continues to prove its indisputable

merits. ! The low and high "scud" which

!

STRATEGIC AIR COMMAND

,5 '

-once negated bombard ent results, the and ,tool on' their way to "ad

rain squalls and mists which once made vance base" at Panama.

it virtually fruitless to drop at all; yes, General Ramey was prepared,however,

t

even the old emergency ethod of bombing should they n9t arrive. In the bomb-bays'

,by, watch-navigation \time coordinates of hfs Superforts were special repair kits,

when weather the target are for use on just such With

all things of the past. I:Radar bombing is llim were extra mechanics, expert trouble-

here ,to stay. ! ' shooters who are accustomed to catering'

A milestone of inestimable importance to ,all the eccentricities that the big Super

in the overall scheme of global air opera

tions has been successf4lly passed. Adapt

able as airpower provell to be in time ,of

war, the freedom of allowed

by peace has ,given lithe opportunity

,extend to 'an amazmg, degree the flexI

bility and mobility of lur airpower. Day

after day, the tremen ous strides taken

in the field of mobilityre freshly accentu

ated. The future is 1i1+tless; the present

but a small preview' of the possibilities

we see lying over the Horizon.

Our new concept of/flexibility was re

cently tested with of the U.S. 8th

Ail' Force stationed at fort Worth, Texas,

XB-45 is a significant development in that

One Saturday several weeks ago, complete

it is America's first operational bomber

ly without warning, eIght Supedorts of

utilizing jet propulsion. (AAF photo.)

the Fort Worth group were ordered to

Panama. They were to Irep'ort to the Com

forts develop. Within minutes after land

manding General; Cafibbean Air Com

ing at Albrook, shortly after midnight

mand, less than twent:r-four hours later,

Saturday, they were at work the on

/II'e)J(tI"ed to conduct fombnt operations.

planes. Spare parts were on "hand; extra

, At dawn on Sunday, tne Superforts were

" assistance available, 'Not a man from the

at Albrook Field, Parama. They were

Panama command was required to'service

lnaded with gasoline and practice bombs.

those aircraft. Albrook was merely a serv

Full maintenance had been completed.

ice station for gasoline and bombs. The

They had traveled something' over 2,000

operation of making those bombers com

'I' I bat-ready was accomplished by the

1111 es. i

Here is how it was done: the unsuspect

bility and mobility of the strike force itself.

ed field order had beer! sent to Brigadier Let me emphasize once again: neither

General Roger Ramey], commanding the General Ramey and the 8th, nor Air

iith Air Force, dUring iSaturday morning. Transport and Materiel Commands, had

Simultaneously, field Iorders were dis-' any idea, prior to Saturday morning, that

Jl"tched to the Commarding General, Air such a mission would be ordered. Yet they

'1 ,'ansport Command, I and Commanding were on their way in just over, six hours.

G,'neral, Air Materieli Command. They That mobility is just as adaptable to Alas

\\ ','re directed to sUPI10rt 'the operations ka, the Aleutians, Japan, the Philippines,

liEder General RameYis command. That Hawaii or Germany as it is to Panama: We

[,iternoon, five C-54 Sk:ymaster ,transports have, made it so; we' will make it e';en

--loaded with spare patts, extra mechanics more BO.

I

MILITARY Rl"VIEW

In a very "real "sense,the" aerial task

forces of today-small, hard-hitting, pow

erfljl arid moving in to replace

the ponderous masses of men and equip-.

ment which comprised striking forces of

any type in previous year,,;, "We have

tuned our equipment and Gur men to that

concept. 'lYe have placed (}ursel-,es liter

ally .on instantaneous notice" for any

emergency.

In our command rooms at headqual'ters

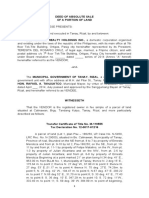

B-36 and B-29-Long range. very heavy

bombardment planes expected to be em

ployed by Strategic Air Command for the

immediate future. (AAF photo.)

both in the field and here in Washington,

the status of aircraft, of aircraft crews

and of maintenance personnel is modified

and corrected as fast as changes occur.

'lYe know to the last man and to the last

airplane and engine what we have avail

able and how quickly it can be made avail

able. We are swiftly reaching our desired

goal: that of being a production line of

available power.

Finally, we reach our third policy: the

concept that range is no obstacle, and the

emphasis the Air Force must-by virtue

of its striking power and available weap

ons-place upon its role as a" means of

maintaining American national policy.

Accepting as fact that American "Air

Power is America's most effective weapon

for peace, it is self-evident that geographi

cal restrictions cannot be countenanced.

They dmnot be countenanced in planning,

in training or in actual flight.

Strategic Air Command" is en

gaged 'in a rotation policy without pl:ece

dent" in military annals. Our cOll'\bat"

crews, in an average year, are seeing"

training and duty in the United States,

Europe, the Far East and the Far North,.

They are learning their geography as they

fly. They are learning that this world of

ours,: en the airman's scale, is" an ever

contracting globe. "They are gammg,

'through that knowledge, skills essential to

the future defense of this country. The

airman who recognizes the complete po

tential" of the machine he has mastered

can better appreciate the potential of the

foe he may some day have to face.

Our global orientation program is not

confined to a single crew or a single unit.

If will be standard operating procedure

throughout Strategic Air Command. It

will affect, over a twelve-month period,

every squadron and every crew, It is our

own interpretation of the global concept.

Its value,for the preservation of peace, or

for effective operations in time of war,

cannbt be over-emphasized.

:\lodern warfare, even as warfare of the

future, will be opened by powerful air

assaults which will- seek by a swift se

ries of paralyzing attacks to destroy'the

opposing air forces or to at least reduce

them to ineffectual units. Coincident \\'itn

or closely following these 01:' rations comes

the ruthless smashing of he centers of

industry and population. Paratroopers

and airborne troops then ize key points

of the battered country and surface forces

follow.as swiftly as possible to consolidate

the victory and occupy the country.

This is the blitz pattern of WQrld War

II. Poland fell in seventeen days. Xorway

and Belgium in two weeks. The capitula

tion of Ft;ance and the eviction of the

British Army at Dunkerque actually took

forty days-from 10 :\Iay to 19 June 1940.

Crete, Buna, and Corregidor are a

few other examples of the application of

airpo{ver and aIrborne to mod

ern \\iarfare.

I

" '" " , 'i "STRATEGIC AIR COMMAND ' ",," ':'7

. New weapons h,e" . .Just category,

mcrease the destructlv" and, deCISIve ca- 1'; B-36,, mIghtIest bomber ever. de

of such an I pffensive pattern.';eloped by this or any other nation. It will

The tempo of warfare is going up ali the open another era in the development of

time. United States Allmy ground airpower; of th,e Very

have already swung mto B"mbal'dment aIrplane capaole of reachmg

,the airborne program;; they' realize it" any spot on the globe and returning to

flexi1ility and its capabilities. The Army its' base.

and its equipment ari being redesigned Thel'c is the B-50, the drastic-ally

for airborne warfare. It is the responsi

bility of Strategic Air 'Command to main

tain its striking force iJ;. being in the state

of readiness J' have desfribed so as to diR

courage any potential enemy, whether by

:,urprise or announced fttack, from under

taking aggressive act. ion against this

country.

In air war, as in II VIal', there are

three phases, assault, retaliation and de

ci:;ion. Decision is based on success in

P-84 "Thunderjet" held the U.S. speed

I

,

record of 619 mph. (AAF photo.)

modified and more powerful version of

Boeing's battie-tested B-2(J. -Only slightly

farther ahead lie jet-powered bombers and

with them will come fresh t"chniques. For

in an era of speed, mental processes must

te as keyed to the times as the machines

which dictate the rate of pl'ogre,s of the

. times.

(,jehel' of the other two phases. Ao demo

Our fighters are improving with equal

r', "tic and peace-lovin

1

den,Y

rapidity. The P-80 Shooting Star, still

the role of the aggressor, It IS our eVI- '

a "radical" departure in 'lesign and en

.' ':nt responsibility to sufficiently strong

vine, will be on the obsolete \jst in a mat

:OJ defeat the enemy and by re

ter' of months, faster, longer

: ,diatory action, ev<intually gain the

ranged types already threaten to outdate

"(;c;ision. I

it. Such .frequent changes, such rapid ob

The evolution and development 'of new

sdescence forces combat pilots and staffs

:r,apons, with ever iincreasing speeds,

alike to revise constantly their concepts

l "nge and firepower, a continuing ef

and be continually undergoing training.

:",cton the capabilities of Strategic Air,

',r,mmand in range andl striking power. We A command forced to change its think

,etognize as a combat.] unit, even ing radically and often is an alert, ac-'

:' .fIre keenly than othbr' elements of our tive, progressive and hard-hitting organi

defense structure, that each new zation, That is the goal toward which

",yelopment is changirig previous concepts 'Strategic Air Command' is directing its_

: Strategic Air Power:' . efforts.

Community'Relations

. I '. ,

and

Army Advisory Committees

Colonel Guy V. Mille,r, Field Artillery

Chief of Information, Army

oDR has no greater responsi

bility today than that of establishing and'

maintaining cordial and intelligent re

lations with the American people. An in

formed nation is an intelligent nation and

the American Army has nothing to fear

f;'om such a public. '

In ,fact, if the American Army is to

dischai'ge the responsibilities imposed

bn it intelligently and properly, it must

-take the Amel'ican people, into its confi

hlence, reveal its needs fol' future security,

and above all else, seek the reactions of

the people upon whom we must depend

for our very existence.

"I

Thus, community relations constitute

one of the major activities of the Army

at the present time. It is vitally essen

tial that the Army's plans and prob1ems

be understood, and that there be a frank

and friendly relationship Ht all times be

tween all Army personnel of, all com

mands, no matter at what level, and the

civilians of the forty-eight states with

whom we deal. It is particularly impor

tant that this understanding exist between

the ,posts, camps and stations and the

communities sUlTounding them.

The Second Army has met this com

,munity relations responsibility-and con

tinues to meet it every day. Major General

Manton S. Eddy, the Deputy Army Com

'mander, has wTitten every post, camp and

station commander in the Army's seven

state area suggesting that an' officer be

designated to handle community relation

ships with nearby cities and towns. This

staff officer visits each town in the vicinity

at least once a month. He calls upon the

mayor, chief of police, the chairman of

the Army Advisory Committee, if one

exists in the town, and other leading and

influential citizens. He is a liaison between

the Army and community clubs and civic

organizations such as the Lions, Rotary

and Chamber of Commerce. He helps them

secure speakers and progTams for their

meetings, utilizing every opportunity to

bring about closer and friendlier relations

between the community and the nearby

post, camp or station. .

In cementing good commnnity relations,

no medium has been more helpful to the

Second Army than the Army Advisory

Committee. It has been ont;! of the best

sources of information that we have

botH to inform the public un what we are

doing, and to tell us what the public thinks

of the Army"

The idea for the Army Advisory Com

mittees had its origin in the mind of Gt;!n

eral Eddy when he was ,in command of the

former Third' Service Command. At that

time, the Army was much concerned over

the seeming inertia of the people. The

Army had important commitments abroad

which it could not carry out unless suf

ficient manpower was provided.

ing was almost at a standstill. We were

I

AND THE ADVISORY ' 9'

witnessing ,a publie ind

J

ffere1!ce that

quently follows ,a long J:ar: '

, It Was decided 'in Third Service l'e

'Command to take the\ p oblem directly to,

the, people. It was beli ved that, if given

the' facts; the people provide the

Army with the soldiers lit needed.

Funds which were made available for

recruiting made it to organize

these Committees. A' series of luncheons

was held . . altimore,: Pittsburg, Phila

delph'a, ,Har 'sburg, a*d Richmond. To

these ons were linvited the most

prom' ent civic leaders p'f those respective

cities; leaders of civic clubs, veterans 01'

g'anizations, educators, Ithe clergy, busi

ness and professional These civic

leaders were requestedl to assist in the

nationwide recruiti'n

g

campaign.

The response to the for help was

remarkable from thei very beginning.

These leaders in business and the pro

fessions were not sympathetic but,

were as much concerned as we were over

the gravity of the Arrriy's situation.

When told how it was for the

Army to have recruits ]immediately, mer

chants in all towns donated window space

for advertising. I,

Sponsors for radio put in a

good word and business firms sponsored

outdoor billboarus. I

The schools cooperated by permitting

our recruiting people address students.

and many college gave their

time and facilities to help the Army.

'This kind of coopetation resulted in

the Second Army securing more than

twenty per cent of one million men

that .joined the Army Iast year.

From that beginnink, the Army Ad-'

visory Committees exp'anded to their

present community 'role. Tod'ay

there are 162 established and

ill nctioning in the seven' states of the

Second, Army Area, wdh a total member

ship of more than 3,OOP men and women.

The Committees are distributed asfollows:

,

Indiana,,26; Kentucky, 15;' Ohio, 30; West,

Vi'rginia, 13; Virginia,' 20; Mal:yland, '8;

'Pennsylvania,! 52. \

Briefly, the mission of the Army Ad

visory Committees is as follows:

1. To promote and participate in pro

jects will foster good relations be

tween the public and the Armed Forces.

2. Give public' endorsement, when justi

fied, to Army sponsored ,endeafors such as

the recruiting program, the organization

of the Reserve Corps, and the National

Guard.

3. Assist in scheduling parades, exhibits

and other'local military affairs at public

gatherings.

4,. Assist in disseminating information

about Army plans and releasing informa

tion to the press and by talks and speeches

before civic, educational and religious

groups.

5. Inform the Army Commandel' of pub

lie tr,ends and opinions insofar as they

feet the Arm8"s program in the commu

nity, and to make recommendations on ap

propriate military matters which involve

community interests. In fact those Com

mittees act as "barometers" of public opin

ion' relative to military matters that con

cern the public.

The Committee members are chosen with

care and represent.. the outstanding men

and women in the various,communities. In

selecting men:)bers we seek to avoid "yes

men." On the contrary, preference is given

to individuals who are willing to express

their opiniqns with vigor and candor.

These Committees are composed of civil

ians, selected by civilians, and run by

civilians.

The Committees meet periodically, every

quarter if pOSSible, 'and at the call of

the chairman. Our District Executives

keep in constant personal touch with com

mittees and the' Deputy Army Area Com

mander carries on a continuous correspon

dence with committee chairmen ,through

out the Army Area.

10 . " ., i' MILI'TARY REVIEW

The work of these ,Committees is no one- lights of current activities of all compo-'

sided affair. The has a. distinct nents of the armed forces.

obligation" in return. We must, provide We must,especially invite criticism of

the Committees with factual and timely our activities and act upon it with intel

. information on military matters that con- ligence.

cern the public. We must conceal nothing is interesting to know that the \Var

that the public should know. ' Department was so favorably impressed

with the Army Advisory Committees or

We must stand ready at all times to

ganized in the Second Army Area that it

receive the Committee's recommendations

'directed all Arl11ies to organize similar

and assist in developing them.

committees. Such committees, throughout

We must, furnish the Committees, peri

the United States, are now in the process

odically, with bulletins covering the high- of being organized.

A total security program has still other ,major aspects. A military

program, standing alone, is useless. It must be supported in peacetime by

planning for industrial mobilization and for development of industrial and

raw material resources where these are insufficient.

President BaiTY S: Truman

The fact remains, however, that nations still talk. and act, in terms of

force. So long as that is the case, disarmament by us alone would deprive

us of all' ability to promote the cause of peace. It would do more-it would

expose our people to the greatest peril. The paramount point 'is that in this

i day and age, our foreign policy, fair and just as it is only as firm as the

military forces that sustain it. Maintenance of military forces in strength, in

this period of transition from war to peace, is our sure safeguard. That will

cost money, but no investment will pay such big dividends.

Secretary of lV(lr Robert P. P(lffp/"'Iln

I

The dArmoredDivision

In

eratlon "Cobra"

1

Lieujenant Colonel H. M. Exton, Field Artillery

Inst uctor, Command and General Staff College

1

T

Introductl

1on

HERE have been al:ticles

covering the general attack of the U.S.

. First Army which out of the Nor

mandy beachhead, drov1 the German for

ces to the east in a warl'of movement, and

hastened the end of the' war. This article

will briefly touch on thel attack of the VII

Corps which the First Army

attack, and then discuss more completely

the attack of the 2d !Armored Division

i

which in turn spearhea1ded 'the attack of

I

the V I Corps. I

This breakthrough attack of First Army

was labeled operation "bobra" (Map 1).

J

Mission of Corps

.. f h hII C

ThemiSSIOn 0 t e r orps was to

make a quick break through the enemy's

front line, push south !'between l.\1:arigny

and St. Lo, and establish a defended cor

ridor between these two points through

which combined armored-infantry ele

m"llts would drive and pivot in the vicinity

oi :\Iarigny, rush soutn and west to the

between Coutances! and Brehal. The

I'lIrjlOse of this drive by the armor was

t" cut off enemy forces 'I facing VIII Corps

on the right, and assift in the odestruc

tl"l1 of these forces; land to block the,

n',' ,vcment of enemy from

t Ill' south or east. i

Preceding the attadk by the gl;ound

m";ts. a gigantic armada of bombers and'

lic'.bteis was to accomplish a satUI'ation

b"lllbing of the breaktHrough area in the

g' ..,\test concentration Iof air power in

i

support of ground forces in the -history of

warfare.

The VIII Corps was to attack in con

junction with VII Corps to destroy the

enemy on its front.

The XIX and V.Corps on the left were

to attack after D-day and pin down enemy

reserves east of the Vire River.

Missions of VII Corps Units.

For this operation the VII COI'PS con

sisted of six strongly reinforced divisions:

The 1st, 4th, and 30th Infantry Divi

sions, and the 2d and 3d -Armored Divi

sions.

The plan of the attack is shown on Map

2. The missions assigned to the dif

ferent units were:

1. The 4th, 9th, and 30th Infantry Di

, visions were to attack, following the ar

tillery and air preparation. to deal' the

IVIarigny-St. Gilles gap as' rapidly as pos

sible for the exploiting forces.

2. The 4th Infantry Division was to

protect the gap from attack from the

south and clear the route of the 3d Ar

mored Division within its zone.

3. The 30th Infantry Division was to.

protect. the left flank of the corps liene

tration, continue the attack to seize a

cros'sing over the Vireo River, prevent

enemy reinforcements from the east from

crossing the Vire, and then clear all traf

fic in its zone- fOl: the 2d Armored Division.

4. The 1st Infantry Division, with Com

bat Command "B" of the 3d Arm'ored' Di

vision 'attached, was to drive through the

12

'MILITARY REVIEW

gap cleared by the 9th In-fantry Div{sion,

'turn rapidly to southwest, block alid

assist in destroying enemy forces in front

of the VIn Corps between Coutances and

Fontenay, and maintain contact with the

3d Armored Division on its left. Movement

through the gap was to commence on two

Division attached, was to strike through

the gap cleared by the 30th Division to

seize initially the area shown on Map 2,

in. order to cover- the movelnent of the 1st

Infantry Division, and the 3d Armored

Division. It would, push one combat com

puind' to the southwest to the vicinity of

ENGLISH

, ,

,

" 'Ci-I..-\'NNEL' ".',.

ISLANDS

.:f "

MORTAIN

BRITrANY

MAYENNE

.

MAP 1

RENNES.

OVERALL BREAKTHROUGH PLAN

hours' notice from the Commanding Gen

eral VII Corps.

5. The 3d Armored Division, less CC

"E," was to drive through the gap cleared

by the 4th Infantry Division, move rapidly

to the southwest, seize the southern exits

of Coutances, and secure the south flank

of the 1st Division.

6.' The 2d Armored Division, with the

'22d Regimental Combat Team of the 4th

the St. Gilles-Canisy road prepared on'

orders to seize and secure objectives with

in its zone of action as shown in order to

prevent enemy reinforcenients from mov

,ing to the north through this area, and

to be prepared to move on Coutances to

reinforce the 3d Armored Division, or 'to

Jl1oveto the southeast to reinforce the re

mainder of the 2d Armored Division in its

mission. Each Combat Command was to

ARMORED DIvniION IN OPERATION "COBRA:' , :13.

have continuous

P:47s in. addition to reconnaissance

air support.

by the exploit.

contained and by

had been 'secured.

have the follow"

corps front. In addition, enemy reserves

capable of reaci)ing the battle zone in"'

eluded' two Pflnzer and thr,ee infantry' di

visions. However, all would take three'

days or longer to reach the battle front. ,;

Organization for Combat of the 2d

Armored Division

. The of the 2d Armored Di- '

illg'

Parachute Division, '!Lehr" Divi

sion, 2<1 SS Panzer Db{ision, 3d Parachute

I'ivision, and 265th I Infantry Division.

These units were known to be all greatly

under strength. From thirty-five to fifty

t. nks were estimated to be present on the

I . .

vision for operation "Cobra" was as

follows:

Combat Command "A":

66th Armored Regiment.

14th Armored Field ArtiiIery 'Bat.,

talion.

22d Regimental Combat Team from

\" .' "

,4th Division with normal attach

ments.

702d Tank Destroyer Battalion "(less

one company).

Attachments of Engineer, Medicill,

Antiaircraft, and Maintenance units.

Combat Command HB":

67th Armored Regiment (less 3d 'Bat

talion) .

,8th Armol'ed Field Artillery Bat

,talion) .

lRt and 3d Battalions, 41st

Infantry Regiment.

Attachments of Engineer, Medical,

Tank DE'Btroyer" and Maintenance

unit5.

Division

-11st Armored Infantl'y Regiment

(less two battalions).

;ld Battalion 67th Armored Regiment.

Division Artillery:

'62d Armored Field ArtillelT Battalion

i attached) .

fi5th Armored Field Artillery I3at

talion (attached).

!)2d Armored Field Artillery Bat

talion (organic to 2d Armored Divi

sion).

Battel'Y t' 1!)5th AAA Battalion

(AWl (SP).

C. D, 12!)th AAA Battalion.

Division T1'00ps:

Headqual'tel's and Headqualters Com

pany 2d Armored Division.

142d Armol'ed Signal Company.

g:2d A ,'mol'erl Reconnaissance Bat

talion,

24th Reconnaissance S"uadl'on Mech

anized (less one troop) (attached).

Headquarters 195th AAA Battalion

(AW) (SP).

11th Armored Engineel' Battalion

(less five companies),

After the operation commenced. the 24th

Cavalry Squadron, was attached to Combat

Command "A." The 62d Armored Field

ArtUIery' Battalion was placed in general

support of Combat Command "B" reinfgrc

ing the fireH of the 78th Armored Field Ar

tillery Battalion. The remainder of the'

division artillery Coml:!at CbIl1

mand "B" in general support or'it and the

Division Reserve.

Attack. of Combat Command "A"

Combat 'Command "A" was to lead the

attack of the seize the initial

objective in vicinity of Le Mesfiil Herman,

and continue to capture the objectives of

Villebaudon and Tessy Sur Vireo

Following the saturation bombing;about

noon, 25 July, the 4th, 9th, and 30th In

fantry Divisions attacked toward their

respective objectives.

Combat Command "A" started moving

from its assembly area during the morn

ing of 26 July, and crossed the St. Lo

Periers road at 0945. It was initially in

one column but soon split into two columns

with the 2d and 3d 66th Ar

mored Regiment, abreast,' operating with

the 1st and 2d Battalions, 22d Infantry

Regiment., The tank units were delayed

by difficult terrain and passed' through

the '30th Infantry Division, but the Ma

rigny-St. Gilles gap was only partially

cleared. They made contact with the ene

my at 1030 and forced him back steadily.

'By 1400 reconnaissance elements liad

reached St. Gilles anQ. by 1500 the Com

bat Command had a firm hold on the town

and had secured the east-west road run

ning through it.

The advance then continued toward

Canisy in one column against light resis

tance. The conditions of the roads and

terrain, however, slowed the progress. Just

north of Canrsy a railroad underpass had

been blown which caused further delay,

The Combat Command reached Canisy at

1900, again split into two columns and

pushed on astride the Canisy-Le Mesnil

Herman road toward the initial objective.

Further obstacles and strong l'esistance

were encountered, but, by 2400, 26 July.

leading elements were 2,000 yards south

of Canisy. This represented an advance of

eight Jiiilometers for the day.

, TliE' tD 'ARMORED DIVISIO;' ,IN OPERATION "COBRA" '15 '

, . Early 'next m9rning' 27 July, the" ' by of Panzer Divisi?n:.

vance was resumed, ani by 0800 Combat ' However, it contmued Its southerly dnve

Command "A" had seized Le Mesnil Her- and by 2.0.0.0 had captured Percy.

,111an. The positions then consolidat- The 2d Battalion, 66th Armored Regi

ed. The 1st Battalion, 6!pth Regi- ment, and the 1st Battalion, 22d Infantl'Y,

ment was ordel'ed to reconnoIter III f01'ce which had composed the center column at

toward Tessy Sui 3d Battalion tacking continued its effort to push

toward ViIlebaudon, anF the 2d Battalion through Villebaudon to attack Tessy Sur

was ordered to capturEj Hill 183. The 2d Vireo For thirteen hours the action swayed

'Battalion accomplished its mission at back and forth, until the last of several

15.0.0 and was relieved !by infantry units. vigorous enemy counterattacks by elements

Strong resistance, antitank guns, and road of the 2d and 116th Panzer Divisions was

blocks limited further ,a1vance that day. repulsed and the town was secureq. One

On 28 J\1ly, Combat fommand "A" was enemy c9unterattack employed forty tanks,

attached to XIX Corps 'and given the mis-' in addition to heavy artillery fire, in sup

sion of securing the <borps objective as port of the infimtry. The 14th Armored

shown on Map 3. The attack was launched Field Artillery Battalion, which was sup

in thre'e columns. east column at- portillg Combat Command "A," was twice

'tacked toward Tessy ,iSur Vire against suri'ounded by the Germans, and had to de

tanks, antitank guns, 'and infantry sup- fend its position with direct fire and

ported by artillery. progress was infantry taCtics. By nightfall the 1st Bat

'made, and by 220.0 high ground south of talion, 22d Infantry held the town and

Le Mesnil Opac had 'seized. At one the 2d Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment

time, the column was Jcut by a German moved to an <;lssembly area northwest of

counterattack but thel enemy elements the town.

were surrounded and reduced: The center

The Commanding General, Combat Com

column seized the higH ground north of

mand "A," believing that his command

:Jloyen, but found the strongly held

would be entirely cut off if he conul1itted

by superior enemy forces. A frontal at

the balance of his force with the tank

the it tack on town was lunsuccessful so

force at Percy, requested and i'eceived per-

was decided to' make 'a wide encircling

. mission to' concentrate all of his efforts

movement to 'approach (he town from the

on the capture of Tessy Sur Vin:'.

rear the next day. The west column, meet

On 31 July, the 1st and 2d Battalions,

ing' little resistance, llushed on rapidly

66th Armored Regiment. attacked along

Hne! captured Villebauqon.

the axis of the Tessy Sur Vire road.

On 29 July the west; column continued

Fighting against con'tinued strong re

ib advance and approhched Percy. The

sistance and, rough terrain, the Combat

center column was in its p,osition

advanced 2,00.0 yards ,during

north of Moyen by infantry of the 29th

the day. At dawn 1 August, the 3d Bat

I llfantry Division and' began its encircling

talion, 66th Armored Reg-iment, joined

movement through There it

the attack from vicinity of Villebaudon'

a strong enemy counterattack'

with the mission of capturing' Tessy 'Sur

by intense :artilleryfire and

tanks. The east column :resumed its attack

Vireo The attack employed a secondary

i'J om Li! Mesnil Opac ht 080.0 and made

road north of t.he highway as an axis.

>low but steady progrells until 18.00 when

Taking advantage of a ground mist" the

il was ordered to break contact and as- battalion overran and destroyed a column

",mble.

, I

, of enemy vehicles, and continued to the

On 30 July, the west fOlumn waS cut off

high ground northwest "f Sur

16

MILITARY REVIEW

,Vireo Two tanks entered' the town at

1030, but were, engaged by a superior',

number of German tanks and destroyed.

The enemy launched determined counter-'

attacks which isoiated' the 3d Battalion in

its position on, the high ground until

later relieved by other Combat Command

" "

tions south of Tessy Sur Vire an'd east of

the Vire River. Combat Command ~ ' A "

moved, in, and secured the town for the

, nigI:it.

Thus, the last objective of, the break

thrpugh phase of operation "Cobra" was

seized, and Combat Command "A" pre-

MAP 3

ROUTES USED BY UNITS

OF 2d ARMORED DIVISION

LEGEND

--CCnA" -'-CC"B"-DlVRES

units. At 1500 the 1st and 2d Battalions,

66th Armored Regiment, and elements of

the 2::?d Infantry, attacked astride the

highway. The enemy off,ered strong re

sistance with artillery and many Mk IV

and Mk 'V tanks in concealed. positions

along the road. However, continued pres

sure by the Combat Command "A" un'its

forced the enemy to withdraw to posi

pared to continue its advance to the south

the following day.

The mission of Combat Command "A"

had been not to gain ground but to hold

off enemy reinforcements coming from

the east. The constant, battering, offen

sive tactics of the combat command cost

it a high percentage of its medium tank

strengt/1, but it kept the major elements

ARMORED 'IN OPERATION "eOBRA"

1,7

I ' . ,", ' , "

, :of both the 2dand Panzer

:' occupied, apd pI'evented the

?f a cooh,nated' counterof

fenslve whICfl wouldtave affected the

course of, the entire oPfration. The cap

ture of Tessy Sur Vire the withdraw

al of the enemy to the \ east bank of the

Vil'e River completely the German

,chances of interfering i with tlie opera

tions which were by tpat time nearing

the BI'ittany Peninsulal

Attack of Combat Command "B"

The attack of Combat Command "B"

was initially delayed by heavy traffic on'

the roads, and in waiting Combat

Command "A" to clear. The reconnais

sance a,nd advance guard cross

ed the St. Lo-':""Periers road at 1100, 27

July. Combat Command "B," in one col

umn, followed and

Canisy, thence to the

1500 yards southwest

Pont Brocard road,

continued through

southwest. About

of ,Canisy on the

an enemy, position

astride Le road was engaged. An en

of the enemy's left flank and

bombing attacks by the Isupporting P'47s

eliminated the resistanceI and the advance

was continued in two ,columns. Dangy

was seized at 1900 and Ront Brocard was

occupied by nightfall. ;Elements of the

82d Reconnaissance which was

covering the Combat Command "B" ad

vance, reached Notre Dame de Cenily at

2400.' This represented an advance of

twelve miles for the day"

A rather interesting aftermath of this

came after the war when Gen

eral Fritz Bayerlein, cO,mmander of the

Panzer "Lehr" Division was captured.

He stated that he had bebn having a staff

meeting in Dangy at 1730, 27 July, when

Amerkan tanks approached the town.

He and his staff hid in oue of the houses

while the tanks, passed through, and

when'they were gone, made good 'his

escape. He found a mooile radio station

and notified his corps !commander that

nothing remained 6f his Idivision.

!

.On 28 'July, the 82d \ '

Battalion continued its advance, and its

reached _Lengronllil, a, nd the, Sien,

ne RIver. An advance task force, consist

ing of one company from the 67th Ar-'

mored Regiment, and one company from

the 41st Infantry' Regiment, rapidiy

pushed forward and seized the crossroads

on the Coutances-Gavray highway at

Cambernon.

During the early afternoon, the Ger

mans launched a stiff attack from Cerisy

LD Salle toward Pont BrocaI'd and Notre,

Dame against the right (north) column.

The intensity of this attack required the

commitment of the Division Reserve

which had been following Combat Com

mand "B." A' coordinated tank-infantry

attack, was launched by the Division Re

serve toward Cerisy La Salle at 2100.

The enemy force was dispersed and the

town was occupied by midnight. The

right (north) column in the meantime

had pushed on west of Notre Dame in

order to maintain the momentum of the

dri,:,e to the final objectives.

On 29 July, elements of the 4th Infan

try Division took up positions protecting

the flanks of Combat Command "B" and

consolidated its positions. In the morning

'a strong enemy force of paratroopers

supported by tanks and artillery attempt

ed to break through to the south at the

cross roads just west of Notre Dame.,

The covering force of infantry from the

4th Division was driven 'back into, the

al'ea of the 7,8th Al'mored Field Artillery

Battalion which was supporting the Dd

vance of Combat Command "B" to the

west fl'om positions al'oun,d this cross

, roads. The artillerymen became infan

tl'ymen for the occasion, and with direct

howitzer fire, beat back the Ger

man attack, destroying seven' tanks and

kiI1ing 126 men.' Elements of the Divi

sion Reserve then mopped up the

nants.

The 1st Battalion, 41st Infantry, and

MILITARY REVIEW

.18 '

':'the 1st' Battalion, 67th Armored Regi

, ment continued the advance and captured

LengroIjne by, 1530. O)ltposts were placed

at St. Denis Le Gast and Hambye.

The task, force of one infantry com

pany and one tank company, which had

reached Cambernon on the 28th had been

cut off for several hours, but held 'and

improved its position under the protec

tion of artillery fire.

The 2d Battalion, 67th Armored Regi

ment, and the 3d Battalion, 41st In

Jantl'Y, advanced toward Cambernon, oc

cupied high ground on the left of the

ro'ad, and, established contact with this

isolated task force. The Division Reserve

was given the mission of blocking enemy

escape routes as far west as GrimesniJ.

Shortly after dark, while units were' still

moving into ,position, a German force of

600 infantrymen and tanks of the 2d SS

"Das Reich" Panzer Division assaulted

the Division Reserve and broke through

pOl,tions of its position in a fierce engage

ment resulting in severe casualties to

both forces. A major part of the German

force: pushed through, overran the out

post ,at St. Denis Le Gast, and turned

west. It then ran into the position area

of the 78th Armored Field Artillery Bat

which, with l(j5-mm direct fire at

ranges from forty yards up, and with aU

available automatic weapons, completely

destroyed the German column. This en

gagement lasted until dawn 30 July.

:At about 0200, 30 July, another Ger

man column of ninety vehicles and 2,000

men moved south over secondary roads

onto the Cambernon-St. Denis road and

hit the 2d Battalion, 67th Armored Regi

ment, and 3d Battalion, 41st Infantry.

The terrain was such that the Gel'luan

vehicles, could not move off the road, so,

when the leading tank was destroyed, the

column came to a halt. All weapons, in

cluding artillery from the 78th Field Ar

tillery Battalion not engaged in the fight

in its area, were brought to bear

on' this column. Every vehicle' was de

stroyed 'and an estimated 500, enem);

killed.

These two break"out attempts' repre

sented the last coordinated 'gasps for,

of the trapped enemy forces to

the north, and on 30 July, Combat Com

mand, "B" and the Division Reserve

were ordered to assemble an'd reorganize.

The sector Was turned over to the '4th

Armored Division and the 1st Infantry

Division. Thus Combat Command "B's"

breakthrough phase of operation "Cobra"

was completed and the division less Com

-bat Command "A" occupied assembly

areas in vicinity of Pont BrocaI'd to pre

pare for future action to the south.

Conclusion

During the July phase of operation

"Cqpra," the 2d Armored Division killed

and captured 5,000 enemy, and de

stroyed 500 vehicles. The division itself

suffered 676 casualties for the period.

This operation was the first time in

World War II that a U.S. Armored Di

vision was used as a divil:lion in the clas

sic role of armor passing through a gap

created by infantry, and then exploiting

the breakthrough. The outstanding sucC'ess

of this operation created the opportunity

to shake loose the U.S. Third Army for

further exploitation. -

It should be noted that the 2d Armored

Division was a "heavy" division. In other

words, its organization 'Consisted of two

armored regiments of three tank battalions

each and one infantry regiment of three

battalions as'opposed to the later armored

division's three tank battalions and three

infantry battalions. This superior tank

strength gave' the "heavy'" armored di

vision the shock force which was ideally

suited for an action such as operation

"Cobra." ,

This was also the first tfme that fighter

bombers were used in close support of

Flights of P-47s !!ontinually re

lieved each other so that each combat com

19 THE ARMORED IN "COBRA" "

mand always had fightJ support. An air quickly, depioyed and pushed' on, tlirotigh'

liaison officer rode in' a jtank with the ad- oreriveloped the resistance. This' aggres

vance guard, and in a of minutes sivelless resulted in fewer 'lvsses.in men,

CQuid call for bombing or strafing attacks 1'and materiel than deliberate maneuver

on resistance encountered. which would have given the enemy time

Another successful of air- to bring up l'eserves and additional

emft was the use of division liaison planes power. It must be added. however, that

in cooperation with the leading reconnais- this aggressiveness must be

sance elements. This npt only helped to ,Furthermore, to achieve'this coordination,

keep commanders fully I informed of the radio communications must be in, top

enemy, but also was a splendid means of shape. Close and complete iB of vi

controlling the advance: of their columns. tal importance.

1

. This action of the 2d ,Armored Division Finally, 'this action the wis

well demoh8trated that trere is one princi- dom of careful prior planning and the

pIe of armored tactics 1 which cannot be launching, of an armored attack at the

overemphasized. That Is 2ggressiveness. proper moment. The armored division is

The success of the divi$ion was achieved a special weapon which will reap tremen

primarily because units Iwere ordered not dous dividends when employed at the cor

to stop, but to keep driVing regardless of rect time and place, but which may fail

resistance 01' losses. In rany cases, when miserably if employed too soon. 'piecemeal,

the lead tank drew fire, following tanks or at the wrong time.

I

Since all activk theaters of operation were overseas, the United States

Army was wholly !dependent ocean transport in making its strength

effective against enemy. The only way the cause of the democracies could

be vindicated was, to attack and defeat the foe on his own soil. The Axis

powers were as awar!! of that" fact as we were, and they did all they

could to upon it. Germany particularly, from the early d"ays of

Hitler's regime, stressed the of submarines. The

had almost accomplished its purpose in the last war; now there were improved

types of U-boats JvaiIable, air power was an added menace to shipping, and

the Allies again unprepared.

During 1940 a*d the early part of 1941 there were several months when

the Allied shipping losses exceeded the shipping output of the

United Kingdom and the United States by more than 500,000 deadweight tons.

I

The winning of th,e war required not only that losses be offset by new con

struction, but that they be exceeded by a substantial margin in order that

, ,

sufficient shipping! eventually might be available to the United Nations. to

enable them to launch the heavy offensives which were necessary to the

I

defeat of the Axis'

l

There were two means to this end-reduction of the losses

by improved defensive" and offensive measures, and a colossal ship construction

program. Both were pursued with utmost vigor.

! Report of the Chief 0/ Tl'ans}JOJ'tation

Estimates .of Enemy'

. ,

Andrew Lossky .

Formerly with the Order of Battle Section, II Corps

T

Foreword

HE purpose of this paper is to dis-,

cuss some of the methods of estimating

combat strength of enemy tactical units,

as developed in the G-2 Section of II

Corps 'in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy

in 1942-1945. Nearly all conclusions re

below ha';'e been based on observa

tion, of the German Army, and to a lesser

extent of the Italian Army, during that

period.

For, the sake of conciseness, the prob

lem of computing enemy strength will be

artificially isolated from numerous other

intelligence problems,which will be treated

here only 'in so far as they have a bearing

on determining enemy combat strength.

This discussion will be limited to infantry

type units of battalion size during their

commitment in line. Likewise in dealing

with enemy replacements we shall confine

ourselves to discussing ordinary replace

ments arriving at a conventional German

outfit. The intricate problem of determin

ing the composition and estimating the

strength of enemy "battle groups," or

small composite task forces, which were

such a striking feature 0:1; the German

Army, will not be touched upon. Through

out this pape:r it will be artificially as

sumed that we al'e familiar with the com

positiop. and djsposition in line o( enemy

units facing 1s; in practice, of course,

this is by no means always the case.

At the very outset, the reader should,

be warned that, this paper does not pur

port to establish any set of uni versally

applicable solutions to the problems which

beset an estimator of enemy strength. The

fornmlae adduced here are only examples

of a line of reasoning which was found

occasionally applicable to certain specific

German and Italian ,units at a certain

given time. It cannot be overemphasized

that one and the same formula could never

be applied to all enemy ,outfits, or even

to the same outfit at all times; it had

to be checked and revised in the light

of recent evidence before it could be used

in any individual case.

Combat Strength

For the purpose of this paper, combat

strength of an outfit will be defined' as

the number of men which its commander

has at his disposal at a given moment for

immediate infantry combat commitment

without impairing the functioning of the

outfit as a whole. In German units of

company size, under normal conditions,

combat strength usually represented ap

proximately. seventy-five per cent of the

total of the company. In a bat

talion, combat strength comprised ap

proximately two-thirds of the total, in a

regiment it was close to fifty per cent,

while in a division it usually dropped

down to about thirty per cent of the

all strength.

The level 01 basic, infantry training

attained by, all troops is usually the chief

factor: which deterIll:ines the extent to

which the non-combat elements can be

I

, ' . ' ..' . , ' " 'I.' 21 ESTIMATES ?FENEMY STRENGTH

used as a pobl of combat troops. of his own platoon and of its recent losses.

In the German Army, I whllre this level His notion Of the other platoons of his

. was exceptionally high,i nearly the whole company was 'somewhat hazy: Usually he

of the non-combat could 'in, knew from hearsay which companies were

theory be regarded as reservoir of com- on his right and left flanks, but of their

bat strength. Usuany. a erman unit wO)lld strength he heard only vague rumors;, it

begin to draw heavily +n this pool to re- was, therefore, impossible to find out from

plenish its combat element after its casu- him the strength of his battalion as a

alties hadamo.unted to 1pproximatelY fifty whole. His knowledge of rear installations

per, cent of its brigina combat strength. of his company was also limited to hear

The majority of Germ n units could af- 'say for the most part. We should bear in

ford to use up about per cent of their mind that when a German 'company re

non-combat element aJ combat replace- ceived replacements, in the beginning, the

ments before the of total collapse new TI:len usually stayed with the company

, was reached. trains, and the fact of their arrival as

well as their number were either totally

Sources of In ormation

unknown to the soldier in the front line,

Most information of tee enemy has some or known to him in a distorted form. Any

bearing on enemy but the ex- sort of reaJiable information on replace

act significance of item of infor- ments came to his knowledge only after

mation, must be deterlljined separately in these replacements had begun to trickle

each individual Iaccording to cir- through to the line. Thus frequently our

cumstances of the mOll\ent. Here we shall intelligence agencies were able to get

deal only with the common sources fairly accurate information on enemy

of information which Iwere available to losses within two days of their occurrence,

the 0-2 Section of II Oorps. but the arrival of replacements to a line

a. Prisoners of Wai.-Let us assume company could remain unknown to them

that a prisoner of w*r belonging to a, for ten tel fourteen days.

, European army is not' trying to deceive

In a mobile situation, a German soldier

the interrogator, but I states the plain

would come to meet many members of

truth as he sees it. One can hardly un

, his own and other ,outfits; frequently he

derestimate the depth of an average pris

would lose his own outfit and attach him

oner's ignorance. It 'is a common failing

self to another unit; but such information

among many inexperienced interrogators

as he would pick up, besides being frag

to treat every PW as if he were 'a general

mentary, would rapidly become outdated';

staff officer.

moreover, the chaos of mobile actiqn was

Very few individuals are endowed with

usually conducive to the rise of fantastic

the gift of estimating correctly and

precisely the size of a large group to rumors.

which they belong. While a German com- Lastly, the prisoner's state of mind

pany wa's 'in line, only the company clerk should be taken into account. Tactical

and mess sergeant, as well as some' interrogation should as a rule be con

of the medical personnel seemet! to have ducted within a few hours after capture:

had a fairly accurate idea of the strength At this time, the PW, if he has grown up

of 'their outfit; even the company com- in a country where Western Civilization

mander was liable to err' on this point, forms the dominant pattern of Hfe, is

e,<pecially if he happened to be captured. usually suffering from a nervous shock

In a static situation, an average Ger- resulting from his recent experience. He

man soldier had a fair idea of ,the size tends to interpret his own misadventure'

22, MILITARY REVIEW

as a calamity to his' whole outfit,' and,

. to his imagination, the situation of his

'unit appe,u:s to be much worse than it

is in reality. His estimate of its numerical

strength is generally much lower than in

fact obtains. If such a prisoner happens

to be wounded, he invariably has a very

exaggerated view of the losses sustained

. by his outfit.

Deserters from a European army '(with

the exception of "plants") do not change

this picture appreciably. A deserter

possess good information on locations of

weapons, strongpoints, and other instal

lations in his sector, but there is no par

ticular reason why he should take pains

to inform himself of the exact strength

of his 'outfit. A deserter either has a chip

01;1 his shoulder, or, ,vhich is more often

the case, he has lost all heart in, the

fight., In', the first case, he often tends to

belittle' his outfit; in the second case, his

outloo'k on the prospects of his unit is very

gloomy indeed. Hence the above consider

ations on PWs are in a large measure true

with regard to, most deserters from a

European army, when we consider them as

a source of information on strength.

In spite of its many shortcomings, in

formation obtained from PWs and de

serters remained one of our main sources

for estimating enemy strength; often it

was' the only available source.

Fortunately, it was possible to intro

duce certain correctives to PW statements

which tended to bring our picture of ene

my strength closer to the truth. Through

numerous comparisons of PW statements

on strength with the actual figures, as

later revealed in captured documents, it

was possible to estimate the coefficient of

underestimation to which a' vast majority

of German PWs and deserters were ad

dicted" Usually, a German PW under

estimated his company by twenty-five to

thil-ty per cent. With wounded PWs. this

coefficient was liable to be even hie:her.

Thus, if a German PW reported that his

company had .sixty men, it was fairly safe

to assume that its' combat strength was'

at eighty, and its total strength, in

the neighborhood of 100 or slightly highei'.,

In determining which coefficient to ap-'.

ply, as corrective in each particular case,

one had to take into account the person

ality Qf the prisoner and the tactical situa-"

tion of the moment. It was often ad'l'is

able to check with the interrogator who

had dealt with the prisoner. As a rule. the

tendency to underestimate one's unit in

creased during a prolonged commitment

in line in defensive positions;, it became

very pronounced during defensive action

or retreat. This writer does not have

sufficient material at hand to make any

definite statement about the coefficient of

distortion during' an advance. It stands

to reason that the tendency to under

estimate have been very much less

, than during a retreat.

b. Captul'ed Docnmellts.-Captured docu

ments, esv,ecially strength, ration, and cas

ualty reports gave us a very accurate idea

of the strength of the reporting unit as of

the date of the document. Unfortunately,

very few such documents fell into our

hands during a static situation; those

which did, were, as a rule, very old. }lany

recent reports were captured during mobile

operations, but they usually became out

dated almost as soon as issued.,

Captured documents were very valuable

in establishing accurately enemy strength

as of a past date. Thus they served mainly

as a general check on PW statements, and

provided a good starting point for "de

ductive est,iJnates" which will be discussed

later.

c. Observation, Gl'oHnd,and Ai'J".-Ground

observation from OPs and by patrols. as

well as aerial observation and photography.

provided us with only indirect data on

enemy strength. For i!)stance, the number

of detected weapons (especially automatic

weapons) 01' of bunkers and pillboxes (if

they ,,:ei'e not dummies) might give us an

ESTIMATES or ENEMY STRENGTH" ': 23

"i!iea 'Of the minimum fQrce necessary tQ'

man them. But we CQuld never assume

that we had sPQtted all the enemy WeaPQns

and 'installatiQns. MQreQver w:e did nQt

always knQw the exact ,bQundaries between

enemy' fQrmatiQns, and we were liable tQ

'1) atalQss as t'O just which 'Of the enemy

'Outfits shQuld have been credited with each

particular weapQn. Thus direct 'Observa

tion did prQvide us 'Only with a general

];QtiQn 'Of a, minimum number 'Of trQ'OPs

facing us in a given sectQr. The value 'Of

such Qbse'rvation was cQnsiderable fQr

determining' the numerical strength 'Of

an armQred unit. It was also 'Of SQme use

asa general check 'On QUI' QveraII estimate,

Ground QbservatiQn was seldQm 'Of help

in detecting the arr.ival 'Of German re

placements, being 'limited tQ daylight

hQurs, as well as by the nature 'Of the ter

rain. MQreQver, by the time German re

placements reached the area 'Open tQ

ground QbservatiQn, they were usually split

up' int'O such smaII grQUPS, that it was

vil'tuaIIy impQssible tQ recQgnize them

as replacements. I

Aerial QbservatiQn. nQt being 'limited

in PQint of space, was much better suited

fnr'detecting the mQvement 'Of large grQUps

of replacements by CQnVQY 'Or' train. Of

rourse, utmQst cauti'On had tQ be exercised.

in cQncluding that a movement' of troQPs

discQvered by Tactical RecQnnaissance did

involve an arrival 'Of replacements. Once,

however, this fact was established with

reasQnable pr'Obability, it CQuld be assumed

that the replacement P'OQI 'Of the divisiQn

intQ whQse area the CQnVQY was

was being increased by the number 'Of

men' the CQnv'Oy was believed t'O carry.

This infQrmatiQn was 'Of great value in

computing a "deductive estimate" 'Of the'

11nits 'Of the divisiQn in questi'On. Aerial

ohservati'On was limited t'O peri'Ods 'Of g'OQd

weather and visibility, and was thus

j"lther sP'Oradic in natur'e; theref'Ore, it

(,<,uld never be c'Ounted up'On tQ detect all

the replacement c'Onv'Oys 'Of the enemy:

d. A,l1ents.-Civilian agents' ,were 'Of

s'Ome use in detecting the arriv,al, 'Of large,

gr'OUPS 'Of replacements'. 'l'heir main', a,d-'

vantage 'Over 1 Tactical was

that they were usuaIIy in a PQsition llto

keep their district ,under m'Ore 'Or less

CQnstant surveillance. It was als'O' easier

'for an observer from the to -de

termine 'the nature 'Of a cQnvQY and tQ

estimate the number 'Of men it carried.

Agent infQrmatiQn, however, suffers

fr'Om seriQus inherent defects. A vast ma

jQrity 'Of agents have had n'O military train

ing tQ speak of. The c'Omplexities of a

mQdern army are SQ baffling tQ an aver

age civilian, that his military Qbserva

ti'Ons, and especiaIIy his deductiQns, are

liable t'O be very misleading indeed, if

taken at their face value. Much depends

'On the persQnal temperament and 'On

natiQnal characteristics 'Of the Qbser'ver;

frequently he is prQne tQ exaggerate or

to intrQduce elements 'Of his imaginatiQn

into his repQrts.

M'Ost agents either pursue their w'Ork

fQr reaSQns of "filthy lucre" 01' fQ1' SQme

'Other persQnal advantage, 'Or else they

are pure idealists. The fQrmer are usualIy

low-grade characters whose veracity is

at times very doubtful. The latter are

given tQ tinging their repQrts with their

emQtions and with their ideas as tQ the

line 'Of actiQn we should take. >

I RepQrts sent in by partisans frequently

4isplay this latter defect; but on the whQle

they are far superiQr tQ thQse 'Of an aver

, age civilian agent, since most partisans

quickly familiarize themselves with mili

tary pr'Oblems.

Of CQurse, Qccasi'OnalIY'it may be PQS

sible f'Or trained military 'Observers t'O

penetrate behind enemy lines. If they

cQmbine acute PQwers of 'Objective observa

ti'On, ,veracity, and thQr'Ough military train

ing, they can produce excellent

'On enemy trQQP mQvements. Needless tQ

say, in practice such paragQns are usually

t'O'O few tQ man a wh'Ole extensive spy, net-'

wQrk cQvering a 'Iarge area.

In spite of all these drawbacks. we

24

MILITARY ,REVIEW'

could not 'afford to neglect news of enemy

replacement movements prO'Vided by an

agent, especially if, such news were cor

roborated by other agents or

by Tactical Reconnaissance,

Agents' reports and Tactical Reconnais

san5!e were practically the only means

available for a timely detection of arrival

of replacements to a German division,

enemy troops in the line usually being

. ignorant of such movements until much

later. Therefore, whoever tried to esti

mate German potential combat strength

was forced to take into account agents'

and Tactical Reconnaissance reports,

evaluating them, of course, with utmost

caution.

Methodology

'How did one go about estimating the

strength. of a German battalion in line,

using,the sources discussed abo've?

The hulk of information at hand was

usually provided by PW statements. After

. we had applied to them the correctives

described in the section dealing with PWs,

our difficulties 'were only about to begin.

As a rhle we did not capture prisoners

daily from each of the four companies of

the battalion. Therefore, our estimate was

bound to be'somewhat out of date, and

there were discrepancies between the dates

of our for ,each of the battalion's

companies. T correct these defects we

used to have recourse to a "deductive

estimate."

We had to' estimate the losses sustained

and the replacements received by the com

ponents of the German battalion in ques

tion since the last date of our information

on their respective strengths. Then we

had to subtract these losses from our

original estimate, and add to the resulting

, figure the estimated replacements received

for the period. If we sought to know the

,total strength of the battalion, we had

to add approximately fifty men (to ac

count for Bn Hq and services) -to the sum

of total strengths of its companies.

Tn' our deductive' reasoning 'in field

'we could no more than make. a reasonably'

intelligent e!3timate, based primar,ily on

the general tactical situation during the

period for which a corrective had' to be

calc.ula ted.

. German losses were naturally very light

during a quiet period, and increased

during infantry or artillery ac

tion., The normal ratio of German killed

to wounded apparently remained fairly

constant, at about 1 :3. By watching an

enemy outfit closely over a prolonged pe

riod it was sometimes possible to establish

its individual normal ratio of PWs (ex

clusive of deserters) to killed at a certain

given stage of the outfit's history. For

example, we found that in the case of

several top-notch German divisions in the

Mediterranean Theater the normal ratio'

of PWs to killed to wounded was usually

about 1:1:3. In a fairly good average

division this same ratio was close to 2: 1: 3.

Thus the number of PWs taken from such

a unit in infantry action could occasion

ally give us some clue as to the total num

ber of casualties sustained by it, provided

that we were quite familiar with the unit

in question. Of course each individual

formula had to be revised fairly fre

quently, taking into consideration the

nature of the replacements the enemy unit

had been receiving, and many other per-'

tinent factors. Before applying the unit's

individual formula in' each particular

case, the computer had first to cQnsider

what changes the tactical situation of the

period tended' to introduce into the ratio

of PWs to killed in action. For example,

the normal ratio was not even remotely

applicable if during the period under con

sideration' the German unit had suffered

a complete breakdown.

The number of enemy casualties sus

tained from each individual artillery bar

rage Or aerial attack was a matter of

pure c?njecture; it depended largely on

25

ESTIMATES' OF ENEMY STRENGTH '

the terrain and on the defensive works of

the enemy, .

, A ,far more' difficult task was to ap

praise the replacements received by the

Germans. This was the weakest link In

a deductive 'estimate, for there appeared

to be no satisfactory method of accur

ately estimating the numbers of recently

arrived replacements. German PWs usual

ly did' not know the replacement situa

tion in the rear' echelon' of their com

" panies and battalions as of 'the ti'me of

their capture. One could determine the

average rate of flow of replacements; but

this formula worked only for large units

of division ilize, and then only over a

,long period of time. All we could do was

to gather every available scrap of infor'

on 'the divisional replacement

pools.