Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Political Law Case Digests

Încărcat de

laz_jane143Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Political Law Case Digests

Încărcat de

laz_jane143Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

G.R. No.

113363

August 24, 1999

ASIA WORLD RECRUITMENT INC., petitioner, vs. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION (2nd DIVISION), PHILIPPINE OVERSEAS EMPLOYMENT ADMINISTRATION (POEA) and PHILIP MEDEL, JR., respondents. Facts: Petitioner Asia World Recruitment is a domestic corporation with authority granted by the POEA to recruit and deploy Filipino overseas contract workers abroad. Petitioner's principal is Roan Selection Trust International Ltd., a diamond and gold mining company in Angola, Africa, owned by one Christian Rudolf G. Hellinger. Private respondent Philip Medel, Jr., is a Filipino who entered into an employment contract4 with petitioner to work as a Security Officer in its diamond mine in Cafunfo, Angola, for a period of twelve (12) months commencing upon his departure from the Philippines, with a salary rate of US $800.00 a month, plus 50% of the salary by way of bonus or a total of US$1,200.00 a month.5 The parties also agreed that private respondent would work for six (6) hours a day, with one rest day every week and that he would be entitled to overtime pay for work in excess of six (6) hours at the rate of $5.00 per hour.6 Private respondent arrived in Angola sometime in December, 1988. In addition to being a Security Officer, he was made to work as a Dispatcher and Metallurgy Inspector in the diamond mine. During his employment, private respondent elevated the grievances of his Filipino co-workers to the management,7 which apparently strained relations between him and management. On March 10, 1989, private respondent received a letter of termination8 dated March 1, 1989 signed by General Manager A.J. Smith, who informed him that the company was not satisfied with his performance within the threemonth trial period, and that his employment with the company would be terminated on March 13, 1989. The records show, however, that private respondent was repatriated to the Philippines on March 12, 1989, barely two (2) days after he received the notice of termination. Aggrieved by his precipitate termination, private respondent filed on October 18, 1989, a complaint9 for illegal dismissal, cancellation of petitioner's license, refund of placement fee plus interest, payment of salary differentials, reimbursement of amounts illegally deducted from his monthly salary, payment of salaries for the unexpired portion of the contract, damages and attorney's fees against petitioner and its principal, Roan Selection Trust International Ltd. Issue: Whether or not public respondent NLRC committed grave abuse of discretion when it affirmed the decision of the POEA finding that private respondent was illegally dismissed with the modification that salary differential, overtime pay and attorney's fee should be allowed. Held: WHEREFORE, finding no grave abuse of discretion committed by public respondent NLRC, the assailed Decision dated September 13, 1993 and Resolution dated October 29, 1993 are hereby AFFIRMED, with the MODIFICATION that, it appearing that petitioner already partially satisfied the NLRC judgment except for a balance of US $741.98, petitioner is hereby ordered to pay private respondent said amount or its prevailing peso equivalent at the time of payment.33 The Court also finds it proper to award private respondent moral damages, and hereby ORDERS petitioner to pay P25,000.00 as moral damages. Costs against petitioner. Ratio/Doctrine: Security of tenure is a right of paramount value guaranteed by the Constitution and should not be denied on mere speculation.20 Furthermore, the right of an employer to freely select or discharge his employees is regulated by the State, considering that the preservation of the lives of the citizens is a duty of the State, more basic than the preservation of business profit. The burden is on the employer to prove that the termination was after due process, and for a valid or authorized cause.22 For the two requisites in our jurisdiction to constitute a valid dismissal are: (a) the existence of a cause expressly stated in Article 282 of the Labor Code; and (b) the observance of due process, including the opportunity

given the employee to be heard and defend himself.23 As correctly found by the NLRC, there was no valid cause for dismissal of private respondent. Thus As in the instant case respondent claim that complainant was terminated due to incompetence. The burden of proof to [establish] such incompetence rests on respondents. The evidence adduced by them were insufficient to prove the alleged incompetence of complainant. Even the "termination letter" itself does not state the how and why complainant was considered incompetent. It merely stated that the company "is not satisfied" with his performance during the probationary period. Respondent even failed to attach to said letter the rating sheets of complainant for his information as that he may present his side.24 Petitioner, failed to rebut the following findings of the respondent NLRC Records also show that the letter of termination dated March 1, 1989 was received by complainant on March 10, 1989 when he was terminated. He was repatriated on March 12, 1989. Taking into consideration the effectivity date of his termination, and the span of time the letter was received and his date of repatriation, we cannot consider that such is the notice required for a valid termination of employment.28 Jurisprudence abounds on the twin requirements of due process, substantive and procedural, which must be complied with, before a valid dismissal exists.29 The twin requirements of notice and hearing constitute the essential elements of due process. Simply put, the employer shall afford the worker ample opportunity to be heard and to defend himself with the assistance of his representative, if he so desires. As held in the case of International Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Commission, 287 SCRA 213, 227 (1998): The law requires that the employer must furnish the worker sought to be dismissed with two written notices before termination of employee can be legally effected: (1) notice which apprises the employee of the particular acts or omissions for which his dismissal is sought; and (2) the subsequent notice which informs the employee of the employer's decision to dismiss him. (Sec. 13, BP 130; Sections 2-6, Rule XIV, Book V, Rules and Regulations Implementing the Labor Code as amended). Failure to comply with the requirements taints the dismissal with illegality. Applying the above legal criteria, we find that private respondent herein was indeed dismissed without cause and without due process. The need for strict enforcement of the law as well as rules and regulations governing Filipino contract workers cannot be over-emphasized. Many hapless citizens of this country have sought employment abroad to earn a few dollars in order to improve their lot, and provide proper education and a decent future for their children, but have found themselves exploited by foreign employers or recruiters who harass or abuse them. They are deprived of their jobs without cause or at the slightest pretense. Hence, Filipino recruiting agencies must not only faithfully comply with Government-prescribed responsibilities; they must also impose upon themselves the duty, borne out of a social conscience, to properly help fellow citizens sent abroad to work for foreign principals. They must keep in mind that this country is not exporting slaves but human beings, and, above all, fellow Filipinos seeking merely to improve their lives.

EN BANC [G.R. No. 157870, November 03, 2008] SOCIAL JUSTICE SOCIETY (SJS), PETITIONER, VS. DANGEROUS DRUGS BOARD AND PHILIPPINE DRUG ENFORCEMENT AGENCY (PDEA), RESPONDENTS.

Facts: In its Petition for Prohibition under Rule 65, petitioner Social Justice Society (SJS), a registered political party, seeks to prohibit the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) and the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) from enforcing paragraphs (c), (d), (f), and (g) of Sec. 36 of RA 9165 on the ground that they are constitutionally infirm. For one, the provisions constitute undue delegation of legislative power when they give unbridled discretion to schools and employers to determine the manner of drug testing. For another, the provisions trench in the equal protection clause inasmuch as they can be used to harass a student or an employee deemed undesirable. And for a third, a person's constitutional right against unreasonable searches is also breached by said provisions. Issues: (1) Do Sec. 36(g) of RA 9165 and COMELEC Resolution No. 6486 impose an additional qualification for candidates for senator? Corollarily, can Congress enact a law prescribing qualifications for candidates for senator in addition to those laid down by the Constitution? and (2) Are paragraphs (c), (d), (f), and (g) of Sec. 36, RA 9165 unconstitutional? Specifically, do these paragraphs violate the right to privacy, the right against unreasonable searches and seizure, and the equal protection clause? Or do they constitute undue delegation of legislative power? Held: WHEREFORE, the Court resolves to GRANT the petition in G.R. No. 161658 and declares Sec. 36(g) of RA 9165 and COMELEC Resolution No. 6486 as UNCONSTITUTIONAL; and to PARTIALLY GRANT the petition in G.R. Nos. 157870 and 158633 by declaring Sec. 36(c) and (d) of RA 9165 CONSTITUTIONAL, but declaring its Sec. 36(f) UNCONSTITUTIONAL. All concerned agencies are, accordingly, permanently enjoined from implementing Sec. 36(f) and (g) of RA 9165. No costs. Ratio/Doctrine: Sec. 36(g) of RA 9165 should be, as it is hereby declared as, unconstitutional. It is basic that if a law or an administrative rule violates any norm of the Constitution, that issuance is null and void and has no effect. The Constitution is the basic law to which all laws must conform; no act shall be valid if it conflicts with the Constitution.[8] In the discharge of their defined functions, the three departments of government have no choice but to yield obedience to the commands of the Constitution. Whatever limits it imposes must be observed.[9] It ought to be made abundantly clear, however, that the unconstitutionality of Sec. 36(g) of RA 9165 is rooted on its having infringed the constitutional provision defining the qualification or eligibility requirements for one aspiring to run for and serve as senator. Sec. 36(c) and (d) of RA 9165, the Court finds no valid justification for mandatory drug testing for persons accused of crimes. In the case of students, the constitutional viability of the mandatory, random, and suspicionless drug testing for students emanates primarily from the waiver by the students of their right to privacy when they seek entry to the school, and from their voluntarily submitting their persons to the parental authority of school authorities. In the case of private and public employees, the constitutional soundness of the mandatory, random, and suspicionless drug testing proceeds from the reasonableness of the drug test policy and requirement. We find the situation entirely different in the case of persons charged before the public prosecutor's office with criminal offenses punishable with six (6) years and one (1) day imprisonment. The operative concepts in the mandatory drug testing are "randomness" and "suspicionless." In the case of persons charged with a crime before the prosecutor's office, a mandatory drug testing can never be random or suspicionless. The ideas of randomness and being suspicionless are antithetical to their being made defendants in a criminal complaint. They are not randomly picked; neither are they beyond suspicion. When persons suspected of committing a crime are charged, they are singled out and are impleaded against their will. The persons thus charged, by the bare fact of being haled

before the prosecutor's office and peaceably submitting themselves to drug testing, if that be the case, do not necessarily consent to the procedure, let alone waive their right to privacy.[40] To impose mandatory drug testing on the accused is a blatant attempt to harness a medical test as a tool for criminal prosecution, contrary to the stated objectives of RA 9165. Drug testing in this case would violate a persons' right to privacy guaranteed under Sec. 2, Art. III of the Constitution. Worse still, the accused persons are veritably forced to incriminate themselves.

EN BANC [G.R. No. 179817, June 27, 2008] ANTONIO F. TRILLANES IV, PETITIONER, VS. HON. OSCAR PIMENTEL, SR., IN HIS CAPACITY AS PRESIDING JUDGE, REGIONAL TRIAL COURT- BRANCH 148, MAKATI CITY; GEN. HERMOGENES ESPERON, VICE ADM. ROGELIO I. CALUNSAG, MGEN. BENJAMIN DOLORFINO, AND LT. COL. LUCIARDO OBEA, RESPONDENTS.

Facts: At the wee hours of July 27, 2003, a group of more than 300 heavily armed soldiers led by junior officers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) stormed into the Oakwood Premier Apartments in Makati City and publicly demanded the resignation of the President and key national officials. Later in the day, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo issued Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4 declaring a state of rebellion and calling out the Armed Forces to suppress the rebellion. Petitioner Antonio F. Trillanes IV was charged, along with his comrades, with coup d'etat defined under Article 134-A of the Revised Penal Code before the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Makati. Held: WHEREFORE, the petition is DISMISSED. Ratio/Doctrine: All persons, except those charged with offenses punishable by reclusion perpetua when evidence of guilt is strong, shall, before conviction, be bailable by sufficient sureties, or be released on recognizance as may be provided by law. The right to bail shall not be impaired even when the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is suspended. Excessive bail shall not be required. The Rules also state that no person charged with a capital offense, or an offense punishable by reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment, shall be admitted to bail when evidence of guilt is strong, regardless of the stage of the criminal action. All prisoners whether under preventive detention or serving final sentence cannot practice their profession nor engage in any business or occupation, or hold office, elective or appointive, while in detention. Congress continues to function well in the physical absence of one or a few of its members. Never has the call of a particular duty lifted a prisoner into a different classification from those others who are validly restrained by law.

EN BANC [G.R. No. 127545, April 23, 2008] ANDRES SANCHEZ, LEONARDO D. REGALA, RAFAEL D. BARATA, NORMA AGBAYANI, AND CESAR N. SARINO, PETITIONERS,VS. COMMISSION ON AUDIT, RESPONDENT.

Facts: In 1991, Congress passed Republic Act No. 7180 (R.A. 7180) otherwise known as the General Appropriations Act of 1992. This law provided an appropriation for the DILG under Title XIII and set aside the amount of P75,000,000.00 for the DILG's Capability Building Program. The stated purpose for the creation of the task force was to design programs, strategize and prepare modules for an effective program for local autonomy. The estimated expenses for its operation was P2,388,000.00 for a period of six months beginning on 1 December 1991 up to 31 May 1992 unless the above ceiling is sooner expended and/or the project is earlier pre-terminated. The proposal was accepted by the Deputy Executive Secretary and attested by then DILG Secretary Cesar N. Sarino, one of the petitioners herein, who consequently issued a memorandum for the transfer and remittance to the Office of the President of the sum of P300,000.00 for the operational expenses of the task force. An additional cash advance of P300,000.00 was requested. These amounts were taken from the Fund. Two (2) cash advances both in the amount of P300,000.00 were withdrawn from the Fund by the DILG and transferred to the Cashier of the Office of the President. The "Particulars of Payment" column of the disbursement voucher states that the transfer of funds was made "to the Office of the President for Ad-Hoc Task Force for InterAgency Coordination to Implement Local Autonomy. The transfer of fund from DILG to the Office of the President to defray salaries of personnel, office supplies, office rentals, foods and meals, etc. of an Ad Hoc Task Force for Inter-Agency Coordination to Implement Local Autonomy taken from the Capability Building Program Fund is violative of the Special Provisions of R.A. 7180. A Notice of Disallowance dated 29 March 1993 was then sent to Mr. Sarino, et al. holding the latter jointly and severally liable for the amount and directing them to immediately settle the disallowance. Issues: (1) Whether there is legal basis for the transfer of funds of the Capability Building Program Fund appropriated in the 1992 General Appropriation Act from the Department of Interior and Local Government to the Office of the President; (2) Whether the conditions or requisites for the transfer of funds under the applicable law were present in this case; (3) Whether the Capability Building Program Fund is a trust fund, a special fund, a trust receipt or a regular appropriation; and finally (4) Whether the questioned disallowance by the Commission on Audit is valid.The parties were required to simultaneously submit their memoranda in amplification of their arguments on the foregoing issues.

Ratio/Doctrine: The transfer of funds from the DILG to the Office of the President has no legal basis and that COA's disallowance of the transfer is valid. According to the OSG, the creation of a task force to implement local autonomy, if one was necessary, should have been done through the Local Government Academy with the approval of its board of trustees in accordance with R.A. No. 7180.

Moreover, Sec. 25(5), Art. VI of the Constitution authorizes the transfer of funds within the OP if made by the President for purposes of augmenting an item in the Office of the President. In this case, it was not the President but the Deputy Executive Secretary who caused the transfers and the latter was not shown to have been authorized by the President to do so. The COA, in its Memorandum[21] dated 18 July 2005, reiterates its position that there is no legal basis for the transfers in question because the Fund was meant to be implemented by the Local Government Academy. Further, transfer of funds under Sec. 25(5), Art. VI of the Constitution may be made only by the persons mentioned in the section and may not be re-delegated being already a delegated authority. Additionally, the funds transferred must come only from savings of the office in other items of its appropriation and must be used for other items in the appropriation of the same office. In this case, there were no savings from which augmentation can be taken because the releases of funds to the Office of the President were made at the beginning of the budget year 1992. The COA also posits that while the Fund is a regular appropriation, it partakes the nature of a trust fund because it was allocated for a specific purpose. Thus, it may be used only for the specific purpose for which it was created or the fund received. The COA concludes that petitioners should be held civilly and criminally liable for the disallowed expenditures. Held: WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DISMISSED and the assailed Decision of the Commission on Audit is AFFIRMED. No pronouncement as to costs.

EN BANC G.R. No. 167173

STANDARD CHARTERED BANK (Philippine Branch) vs. SENATE COMMITTEE ON BANKS, FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND CURRENCIES

Facts: On February 1, 2005, Senator Juan Ponce Enrile, Vice Chairperson of respondent, delivered a privilege speech entitled Arrogance of Wealth1[1] before the Senate based on a letter from Atty. Mark R. Bocobo denouncing SCB-Philippines for selling unregistered foreign securities in violation of the Securities Regulation Code (R.A. No. 8799) and urging the Senate to immediately conduct an inquiry, in aid of legislation, to prevent the occurrence of a similar fraudulent activity in the future. Issue: Whether or not SCB-Philippines illegally sold unregistered foreign securities Held: Petitioners sought anew, in their Manifestation and Motion2[21] dated June 21, 2006, the issuance by this Court of a TRO and/or writ of preliminary injunction to prevent respondent from submitting its Committee Report No. 75 to the Senate in plenary for approval. However, 16 days prior to the filing of the Manifestation and Motion, or on June 5, 2006, respondent had already submitted the report to the Senate in plenary. While there is no showing that the said report has been approved by the Senate, the subject of the Manifestation and Motion has inescapably become moot and academic. WHEREFORE, the Petition for Prohibition is DENIED for lack of merit. The Manifestation and Motion dated June 21, 2006 is, likewise, DENIED for being moot and academic. Ratio/Doctrine: The Senate or the House of Representatives or any of its respective committees may conduct inquiries in aid of legislation in accordance with its duly published rules of procedure. The rights of persons appearing in or affected by such inquiries shall be respected.

1 2

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Sample Annotated TSM by Brian Greenough Sample02 en Score 22 1 2Document13 paginiSample Annotated TSM by Brian Greenough Sample02 en Score 22 1 2Dani Rodriguez100% (1)

- Coaching and MentoringDocument33 paginiCoaching and MentoringSiddharth ManuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labor Post Midterms NotesDocument36 paginiLabor Post Midterms Noteslaz_jane143Încă nu există evaluări

- Bienvenido Dino vs. OlivaresDocument10 paginiBienvenido Dino vs. Olivareslaz_jane143Încă nu există evaluări

- Environmental LawsDocument84 paginiEnvironmental Lawslaz_jane143Încă nu există evaluări

- Environmental LawsDocument86 paginiEnvironmental Lawslaz_jane143Încă nu există evaluări

- Moday vs. CA DigestDocument2 paginiModay vs. CA Digestlaz_jane143100% (1)

- Land Titles: A C B O 2007 Civil LawDocument28 paginiLand Titles: A C B O 2007 Civil LawMiGay Tan-Pelaez86% (14)

- Osha3165 PDFDocument1 paginăOsha3165 PDFzulafiqÎncă nu există evaluări

- HOLIDAY INN MANILA v. NLRCDocument2 paginiHOLIDAY INN MANILA v. NLRCrobbyÎncă nu există evaluări

- OverviewDocument37 paginiOverviewJC Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- RTCRTC 052721 - PTHCD Report FINAL - No Watermark-CompressedDocument144 paginiRTCRTC 052721 - PTHCD Report FINAL - No Watermark-CompressedItsLOCKEDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Company Profile: HR Practices of Hindustan UnilerDocument6 paginiCompany Profile: HR Practices of Hindustan UnilerRaj ChauhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Compensation and Benefits To Employee Motivation in A BusinessDocument7 paginiImpact of Compensation and Benefits To Employee Motivation in A BusinessirfanhaidersewagÎncă nu există evaluări

- 05-13-14 LAUSD Regular Board MeetingDocument1.075 pagini05-13-14 LAUSD Regular Board MeetinglaschoolreportÎncă nu există evaluări

- Durabuilt Recapping Plant Company Vs NLRCDocument3 paginiDurabuilt Recapping Plant Company Vs NLRCRia CuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krishna MishragkpDocument2 paginiKrishna MishragkpKrishna MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contractor's Red Book - EHSSQ Requirement PDFDocument90 paginiContractor's Red Book - EHSSQ Requirement PDFAhmedHussainQureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interview Questions Format 3Document2 paginiInterview Questions Format 3Hannan yusuf KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- LearnEnglish Reading B1 An Encyclopedia Entry MergedDocument61 paginiLearnEnglish Reading B1 An Encyclopedia Entry Mergeddiu thanhÎncă nu există evaluări

- UberDocument9 paginiUberMadeline ButterworthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tim Chevalier v. GoogleDocument20 paginiTim Chevalier v. GoogleNick StattÎncă nu există evaluări

- Senior Controller Finance Manager in Toronto Canada Resume Karalasingham SadadcharamDocument2 paginiSenior Controller Finance Manager in Toronto Canada Resume Karalasingham SadadcharamKSadadcharamÎncă nu există evaluări

- HR Planning Process in Cocacola, BangladeshDocument36 paginiHR Planning Process in Cocacola, Bangladeshall_r83% (6)

- 00 8 Math - ZCHS MainDocument15 pagini00 8 Math - ZCHS MainPRC BoardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promote YourselfDocument2 paginiPromote Yourselfapi-614474957Încă nu există evaluări

- AMA MBA 603 Short Quiz 9 Week 11 How We Lead PDFDocument6 paginiAMA MBA 603 Short Quiz 9 Week 11 How We Lead PDFYvette SalihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee Absence Reporting RulesDocument3 paginiEmployee Absence Reporting RulesFrancisco RamirezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 Self - Audit - Questionnaire PDFDocument28 pagini02 Self - Audit - Questionnaire PDFFachrurroziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bbui3103 - Employment and Industrial LawDocument19 paginiBbui3103 - Employment and Industrial LawManokaran LosniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compensation ReportDocument26 paginiCompensation ReportLiange FerrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Circular 44 2018 PDFDocument185 paginiCircular 44 2018 PDFjonnydeep1970virgilio.itÎncă nu există evaluări

- Staffing and Leading A Growing CompanyDocument12 paginiStaffing and Leading A Growing CompanyMaroden Sanchez GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

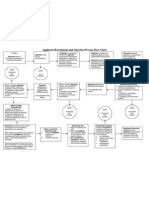

- Applicant Recruitment and Selection Flow ChartDocument1 paginăApplicant Recruitment and Selection Flow Chartants_ramsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vlsicad - ucsd.edu/Research/Advice/star Engineer PDFDocument22 paginiVlsicad - ucsd.edu/Research/Advice/star Engineer PDFKonstantinos ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- M.C Mehta vs. State of Tamil Nadu and Ors.1997 Airsc 699 (India) Neerajachaudhary V. State of Madhya Pradesh 1984 3 SCC 243 (India)Document2 paginiM.C Mehta vs. State of Tamil Nadu and Ors.1997 Airsc 699 (India) Neerajachaudhary V. State of Madhya Pradesh 1984 3 SCC 243 (India)Uditanshu MisraÎncă nu există evaluări