Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Burmaissues: Preparing The Soil For The Seeds of Democracy

Încărcat de

Kyaw NaingDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Burmaissues: Preparing The Soil For The Seeds of Democracy

Încărcat de

Kyaw NaingDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

B u r m a Issues

AUGUST, 1996 VOL. 6 NO.8

CONTENTS

THE ENEMY WITHIN POLITICS GRASSROOTS DEMOCRACY HTJMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES ECONOMICS 6 4 3

PREPARING THE SOIL FOR THE SEEDS OF DEMOCRACY

THE HIDDEN COST OF INVESTMENT LABOUR 7

PUSH AND PULL: ILLEGAL NEIGHBOURS IN THE NEWS 8

...a democratic process for building up democracy must be seen as a ground up process....

Information for Action +++ International Campaigns for Peace +++ Grassroots Education and Organizing

PROPAGANDA

THE ENEMY WITHIN

byCAC s the garish balloons of American politics rain down in this election year, Burma watchers may notice a stark contrast between the US A' s two party-only system and the proliferation of parties, sub-parties, counterparties, organisations and splinter organisations filling Burma's underground political landscape. Is this multitude necessary and effective? If not then why the proliferation? In a study of village politics, Melford Spiro, the dean of scholarship on Burmese culture, once observed that factionalism is endemic on all structural levels of Burmese society. Is there truth in such a bold claim>and how does it affect o n e ' s outlook on Bunna's struggle for peace and justice?

1. Oppose those relying on external elements, acting as stooges, holding negative views; 2. Oppose those trying to jeopardise the stability of the state and progress of the Nation; 3. Oppose foreign nations interfering with the internal affairs of the state; 4. Crush all internal and external destructive elements as the common enemy. In this case, the 'People's Desire', ostensibly a unifying sentiment of the people of Burma, is represented as solidarity against a distinct enemy, rather than a positive cohesion and cooperation towards a goal, such as peace or national development. This essentially negative message encourages and institutionalises conflict between those who are deemed obedient to the nation and those who seek to change or subvert it - The Enemy. While this brief analysis might explain in part how the state maintains its comparatively mundane one party system, does it help in any way to explain the factionalism characteristic of Burma's Opposition movement? One factor may be that most participants grew up and were educated within earshot of the state's propaganda machine, perhaps forcing many to internalise The Enemy as a natural category of social life. Some wellknown splits among opposition groups have been attributed to personality conflicts and an ensuing factionalism that splits members according to their loyalties. Ideological differences tend to help movements grow, as they require members to clarify their ideas and choose among strategies to achieve them. The split may end up as a positive force in the life of each party and each can, hopefully, develop and continue to co-operate. Remarkably, opposition groups, particularly ethnic minority groups with access to civilian populations

and civil institutions such as schools, seem to have patterned their rhetoric after the state they are fighting. Conceiving of The Enemy is a central message of the education system, particularly in the subjects of history and politics. In this sense, a tendency towards factionalism does seem to be endemic, even outside the scope of the state's enemy-making propaganda machine, as opposition groups persist in reinforcing the category and their subjects continue to internalise it. Some organisations have escaped, for at least some time in their history, the most destructive brands of factionalism. Umbrella organisations, such as the Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB) have achieved some degree of unity and cooperation. Consequently, they have also received the strongest attacks by the state. The key to the State Law and Order Restoration Council's strategy for breaking up the DAB was to step-up fighting, then initiate individual ceasefire agreements with its members - in effect to reintroduce factionalism into one organisation that achieved some success by suppressing it. Despite the propaganda on all sides, everyone should consider that the most potent enemy they face is the one which drives them from unity towards petty factionalism, that compels them to follow leaders rather than ideas. Factionalism may or may not be endemic to Burmese society, but the capacity to control it should be within everyone's reach. Without the true intention and skills necessary to suppress the urge to split, factionalism will always upstage war, ideology and human rights as the primary force controlling politics in Burma. It teaches people to look for enemies among their own ranks, yet the untold secret is that factionalism itself, not a government spy or a dissenting voice, is the enemy within.

There can be little denial that postmonarchy Burma has witnessed an avalanche of political and military groups, many of which exist on paper but in reality comprise a light handful of people and very scant activity. Post-1988 Burma contributes a plethora of political and/or military organisations, defining themselves in opposition or alliance to others around them. To wit: NLD, NLD(LA), DPNS, ABSDF, PPP, DAB, NDF, NCGUB, NCUB, KNU, DKB A KIO, M-TUF, SSA M T A SURA, PDF, K N P P , K N P L F , SSO, CNF, ABYMU, ABBSEA, ONSOB and too many others for this list to ever be complete. The Burmese government enforces its one-party system quite effectively, making a genuine and legal diversity of political organisations virtually impossible. The state articulates quite effectively one possible explanation for the 'endemic' nature of factionalism in Burma: the institutionalisation of that important cultural icon - The Enemy. Consider the formula of the People's Desire campaign (see Burma Issues, June 1996):

3 August 1996

POLITICS

GRASSROOTS DEMOCRACY

by N. Chan The United Nations brought the good seed of democracy to our country, but the soil was not yet well-prepared. Statement by a Cambodian human rights worker during a 1995 human rights seminar, explaining why the huge budget and effort of the UN to establish a democratic government in Cambodia may well fail. everal articles in July's Burma Issues discussed how international bodies might help establish an atmosphere in which true peace and justice in Burma could be encouraged to develop and grow. While these international bodies can play an extremely important supportive role in helping move towards this goal, the real success of a democratic movement lies with the ability and readiness of the grassroots to help define exactly what form democracy in the country should take. In practice this involves a complex, careful and deliberate process for encouraging grassroots participation and leadership. When the question becomes how to involve those people at the very bottom of the social pyramid, such as displaced minority villagers hiding in the civil war zones who have no economic base, virtually no education, and little hope for even a meagre survival, the task becomes even more difficult. Rarely is this group of people given a chance to share their concerns and ideas about the future of the country. Worse, many local and international organizations have little or no faith in the ability of these people to even know clearly what they want, or to have the ability to suggest new and more participatory economic and political forms. Yet it is this very important group of people which represents the soil in which the seed of democracy must be planted, and it is this "grassroots" sector which must define what specific forms the new economic and political structures must take if those structures are to truly allow active participation by all. Preparing the "soil" for democracy does not simply entail teaching or training the grassroots. This, in itself, is generally a very top-down, un-

democratic activity based on the premise that they (the grassroots) lack the knowledge and skills necessary for democracy. If the actual process for building democracy in a country is not strongly democratic, how can it result in a democratic future for the people of that country? No matter how poor, poorly educated, or oppressed people may be, they are aware of what they like and dislike, what helps and what harms them, what they can participate in and what is too foreign for them. Allowing the people to express these issues is the starting point for building democracy. While democratic movements may be able to predict very accurately what the poor do want, there is something very empowering and in allowing people to express for themselves what rights they want protected, or what type of political and economic systems they feel most comfortable with. Encouraging the grassroots to participate in this way is the primary process in "preparing the soil for the seed of democracy", but only if that voice is seriously listened too and acted upon. The exact steps in preparing Burma for democracy depend much on the particular situation in which the grassroots find themselves. A"grassroots bill of rights" should be the foundation for the creation of a state constitution which would define the kind of bureaucratic system necessary to fully guarantee and protect those basic rights. This constitution and the ensuing bureaucratic system would be perceived by the grassroots as a guarantee for peace and justice in their future, and they, in turn, would hold on tightly to their roots, guaranteeing their own security and growth. Apart from a constitution, a peoplecentred democracy must elicit the

wisdom of existing traditional political and economic systems at the village level. Effective, just practices should perhaps be institutionalized; weak and undemocratic ways should be tested against the people's common vision of their rights. This latter process would also help protect the grassroots from becoming even further marginalized during the transition from an old exploitive system to a new, democratic one. For example, if the new economic system is based on competition, the grassroots, whose traditional ways are built around cooperation rather than competition, would be unable to participate even minimally, and thus would become victimized by the system. If the new economic system was based on traditional forms, the poor would be able to participate in it comfortably and would have the important opportunity of becoming a more central part of the nation's economic life. Democracy, as an ideology of practice rather than theory, does not become authentic in a country simply by establishing a structure based on successful democracies in other places. Like a small seed, it must be planted in well-prepared soil, and it must get its nourishment and power from that soil, growing in a manner determined by that soil. A transplanted tree may survive and grow in its new environment, but without roots anchored deep in the millions of grains of soil surrounding it can be easily felled by strong winds. A democratic process for building democracy, therefore, must be seen as a from the ground-up process, and must take seriously the wisdom and experiences of the most "grassroots" of the society.

August 1996 3

HUMAN RIGHTS

HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES

by N. Chan

Chin State

n June 2,1996, Captain Nay Myo Aye of Battalion 266 (Burmese army), arrived in XXX Village (village name deleted at request of factfinder) in Chin State. He sent an order to the local village chairman to immediately come to see him. The village chairman was also instructed to bring along two chickens, two tins of rice, and one bottle of cooking oil. Captain Nay Myo Aye demanded that local villagers provide porter services to his battalion. The village chairman later reported that the following conversation between him and the captain took place.

Captain - The government does not give us enough supplies so we have to get food and supplies from the villagers. Surely you understand this. The government is using our supplies to benefit you with border development, so we have to get food from somewhere. Chairman - The government has never carried out any development work in our village. So all the families are struggling very hard just to survive. If something does not change soon, we will no longer be able to live here. We will all move to Mizoram. Captain - Because of your Aung San Suu Kyi, the country is not progressing. She is using her father's reputation to create problems between students and the army, as well as between the people and the army. She is making the country unstable. That is why we can not develop our country. Yes, Aung San Suu Kyi has the ability to lead the country and she is also a Nobel Peace Prize winner, but she grew up in India and married with an Indian. Then she moved to England and again married with an Englishman. She does not want to get married with a Burmese but only with the foreigners. And then, there are many political parties in the country. Most of the political party members are well educated persorwith much dignity, and they can easily lead the country. If you look at Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy party members, you will see that they are only pony cart drivers, trishaw drivers, gamblers and drinkers. Who can accept these people to lead the country? The Burma political situation depends on the political situation in Rangoon. If there are changes in Rangoon, the whole country can be changed. Therefore, the minority ethnic groups do not need to be involved in the country's politics. You just sit and wait for the situation in Rangoon to change. Now, do whatever I asked you to do.

On the following day, Captain Nay Myo Aye and his group came to the village and took eight villagers as porters to carry supplies to an army camp 20 miles away. Since most of the adults in the village were out in the fields, the soldiers took students and children. The oldest was 20 years old and the youngest was just 14. One of the young porters brought back the following report. "Each of us had to carry nearly 30 kilograms (66 pounds) of ammunition and food supplies. We left our village at 4 p.m. and arrived at the army camp about 3 in the morning. We received no rice or medicine. Before reaching the army camp, several of the horses which were also carrying suppl ies, became too tired to walk on, so their loads were added to that already being carried by our group. We tried to escape, but the soldiers kept a very close guard over us. We pray that we will never have to face this kind of experience again for the rest of our lives." Source: Chin National Front Report, July 10, 1996

Captain - Tomorrow all the people from your village must be prepared to serve as porters. That is all. You can go now. Chairman - The villagers are very busy with their planting now which means they sleep near their fields instead of coming back to the village at night. So there are no people are in the village now. Captain - Go back and call them right now. Chairman - Will you please give us time off now? This year all of our crops were destroyed by insects, so the villagers must replant. Already it is very late for planting, and if they do not finish now, it will be too late to get a crop and they will all starve. Captain - Your village is only being asked to serve as porters two or three times a week. Other villages have to go five times a week and they do not complain. Whatever we ask them to do, they do it. Chairman - Our people live only day today. We fear that if we do not work on our farms, we will have nothing to eat or feed our children with.

Shan Refugees

In March of this year, the Burmese military began carrying out massive relocations of villagers in the Shan State. The military's apparent strategy for these relocations is to weaken any local support for anti-military activities by Shan armed groups. According to a recent Shan Human Rights Foundation Report, a minimum of 450 villages have been evicted since April of this year, comprising at least 80,000 people The relocations have al so resulted in an influx of Shan refugees to the Thai/Burma border. Tens of thousands of refugees have crossed into Thailand since April. Unfortunately for these refugees, there are no refugee camps nearby where they can seek refuge. Therefore they have to dis-

3 August 1996

HUMAN RIGHTS

'...they are only pony cart drivers... Who can accept these people to lead the country? ' perse as soon as they arrive in Thailand and simply hide in towns and villages in northern Thailand, seeking small jobs each day for survival. Since they fled into Thailand to escape abuses by the Burmese military, they are not economic refugees, but they are forced to seek jobs for meagre pay as the United Nations High commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other NGOs are not presently providing them any assistance. As illegal person in Thailand they are easily exploited; forced to work at hard jobs but paid only a small amount. When they become sick they are afraid to go to the hospital for fear that they will be reported to the police, arrested and sent back into Burma. Consequently some are dying of easily treatable illnesses. Shans living along the border say that the current refugee influx is unprecedented. They fear that one day, there will no longer be any Shans living in die Shan State. International intervention is necessary to help them find the safe refuge they seek and to help make it safe for them to return to their homes. A Shan woman with three children (7 months, 3 years, and 9 years) fled to the Thai/Burma border on June 1. When the eviction of her village was initiated by the Burmese military, her husband was not at home. In the following story, she describes what the eviction was like. When I was in my village the soldiers came and gave the eviction order. I saw them There were many groups of soldiers. As soon as we knew that Burmese soldiers came into the village, everyone was scared and we didn't dare go out of our houses. We had to leave within 5 days. They gave the order at night, and the next day we started moving. All the villagers started to move their things immediately. We had to move so far. The older people just stayed at home and the women had to carry all their belongings, We couldn't finish moving everything in one day. We had to run away. I have 3 children - one walked, one I carried, and the other I put in a pushcart. When I left I couldn't take everything with me. Since my husband wasn't there, all I could do was take the children. Oh! It was very hard and miserable to move! First I tried to move to Nong Tao, which is not far from my village, but we were told that we couldn't stay there, so finally we moved to Lang Ker to stay with my relatives. No one helped me. I did it all myself on my own, holding my baby all the time. Just mother and baby. My oldest boy can walk, so he walked along. My parents have a pushcart, so I put my smaller boy on the cart, and I carried my baby on my back with me while I carried other things on my front. No one to help. Those who have more belongings had helpers. Oh! It was terrible. My tears were even dropping along the way. Source: Volunteers for the Displaced Shans 072396 Shan Human Rights Foundation 061396 Karen Human Rights Group, KHRG #96-23

August 1996 5

ECONOMICS

The Hidden Cost of Investment: Infrastructure

by C.E.K. hile east and west still disagree over the merits of constructive engagement, economists from both halves of the globe have come to similar conclusions regarding the capacity of Burma's infrastructure to accommodate investments. Large corporations looking to Burma have little trouble dismissing the SLORC's record of human rights violations as politically motivated allegations; however, physical constraints which hamper development and threaten profits can not be as easily dismissed. Both the Foreign Economic Trends Report published by the US Embassy in Rangoon and the Far Eastern Economic Review list four key areas of infrastructure inadequacy that potential investors should be aware of: transportation, energy, communications and education.

Tokyo-Mitsubishi, "You cannot make production plans with such a poor port situation." Having to deal with such inadequacies decreases profits and increases headaches. Energy Power outages resulting from Burma's antiquated distribution system continually plague the country. In the 1994-1995 financial year Burma produced roughly 3,500 million kilowatt hours (MKWH) while 1,308 MKWH (37.4%) were "lost" to illegal line tapping and undeclared military usage. It is believed that the military consumed the majority of the power "losses" which equals roughly two billion kyats worth of energy. Government enterprises were given priority for the remaining 2,192 MKWH while the "left-over" energy was available for private usage. In light of power shortages, private and foreign businesses have been either forced to operate below capacity, or have opted to use their own costly diesel generators to ensure reliable electricity. Either approach translates to a reduction in profits. Communications In an age of increasing technological advancement, global communications have become essential to the effective business venture. In Rangoon, one can be considered lucky to get a telephone call across the town, even luckier across the country Burma's telephone system remains both antiquated and inadequate for the demands of today's global marketplace. Burma has neither a fibre optic communications network nor any access to the internet. Even international fax and phone calls, when they work, prove to be both expensive and strictly regulated. The SLORC intermittently jams Voice of America broadcasts proving that effective radio communication can not be guaranteed either.

Education Perhaps the greatest threat to Burma's economy will be the frightening decrease in an educated and skilled work force. Currently only one in four children completes primary school and the SLORC has been consistently cutting the budget for education since 1991 With the shortage of skilled workers, many foreign investors have been forced to "import" their own employees. While a massive unskilled workforce may benefit some manufacturing industries, the low pay associated with such jobs will have negative effects on Burma's long term economy. Conclusions Who will be responsible for improving Burma's infrastructure? Where will the money come from? The SLORC continues to allocate an increasing percentage of the country's annual budget to defense, and multilateral lenders have been reluctant to fund the SLORC. By 1990, all donor countries except China, and in a limited way Japan, had stopped giving Burma assistance. Western countries have also prevented the World Bank and International Monetary Fund from supporting the SLORC. Clearly foreign investors will bear the brunt of modernizing and building-up Burma's infrastructure a hidden cost many corporations might not be prepared to pay. Sources: Foreign economic trends Report:Burma, US Embassy, Rangoon, 1996 Far Eastern Economic Review 960815

Transportation When French oil firm Total entered Burma, it had to build its own roads, bridges, an airfield and a port before construction on the gas pipeline could begin. In fact, the streets of Rangoon are often clogged with private cars and taxis while the lack of roads and railways into the rural areas has effectively cut off the majority of Burma from any centralized market. Meanwhile annual road building creeps along at 2.3%. Beyond the overland distribution of goods, investors also have to deal with Burma's lack of airstrips and ports. No runway in the country has the capability to handlejumbojets, common to international travel, and the Rangoon Port can not accommodate ships larger than 10,000 tons. Even if larger ships could dock at the country's largest port, there are only two cranes for unloading and ships commonly wait in the Rangoon estuary for weeks before a chance to unload. According to Takahashi of the Bank of

3 August 1996

LABOUR

PUSH AND PULL: ILLEGAL NEIGHBOURS

by Alice Davies

hailand fihds itself host to some 700,000 illegal immigrants, of which the Thai National Security Council estimates there are 101,000 Burmese.

For the Burmese in Thailand, the country is a relatively safe haven from the well documented rigours of daily life at home, among them forced relocations and labour, no freedom of association, a barely self-sustaining minimum wage and high commodity prices. There is already a lucrative trade in smuggling illegal immigrants across the border, allegedly involving Thai police and military officers. The Thai National Security Council (NSC) has said that the decision to permit and register illegal immigrants is intended to counter, not foster this trade and to regulate the illegal immigrants to prevent long term social security and social problems developing. The Thai government is seeking to regulate these people, who are providing a source of cheap labour to ease the country's growing labour shortage. The government has proposed recognising these 700,000 illegal workers in 39-43 provinces (the number varies between reports), for the farming, fishing, construction, mining, transportation and industrial sectors. They will not be able to work in painting, laundering clothes, plant and animal farming, food vending, food and beverage production, repairing bicycles and silver- and gold-smithing. The Cabinet decision, effective from the 1st of September 1996, is that the illegal workers will be permitted to take up employment for a period of up to two years, subject to registration, payment of a 5,000 baht surety by their employer and a 1,000 baht fee for their work permit. They will hold a card similar to the one held by immigrants waiting to be repatriated. 'They will enjoy the same benefits as Thai workers,' said Employment Pro-

motion Department director-general, Prasit Chaithongphan, who also acknowledged that the legal recognition of immigrant workers would have a social impact and may hurt Thai workers where wages were concerned. In its favour, he said that the measure was the only way to effectively monitor and control illegal foreign labour. There is considerable and on-going debate over this plan. While the Thai Cabinet has endorsed the proposal to allow illegals to work, it has refused to interfere in labour issues, saying these are the responsibility of the Labour Ministry. The Labour Ministry has criticised the plan as one likely to cause social problems, pose a security risk and is unlikely to have economic advantages. The Tak Chamber of Commerce Vice Chairman, Suchart Trirarwattana, complained that such a move would encourage illegal immigrants to seek jobs in the country and create a host of social problems, including their affect on the lives and property of local people. The immigrants would not want to return home and the Government would have to shoulder the heavy burden of providing the workers and their children basic necessities and social welfare benefits. In contrast, the Thai Chamber of Commerce chairman, Phothipong Lamsan, has welcomed the decision, saying that illegal immigrants with work permits will help ease the country's labour shortage, which has caused a decline in productivity and exports. 'Foreign workers will not take away jobs from local workers as feared by the Labour Congress of Thailand, because they will get only low level jobs that Thais don't want. When employers need to lay off workers, foreign workers will be laid off first,' he said. The Federation of Thai Industries request to the Industry Ministry for a low wage, free labour zone was re-

portedly warmly received. Here, there would be no minimum wage. In contrast, Sawai Pattano, former labour secretary, now part of the Advisory Council for National Labour Development, has said that 'alien'[sic] workers should receive payment equal to that of Thai workers and that Thailand will be criticised if it fails to ensure equal pay. One editorial pointed out that if Thais are alarmed by the prospect of Thais in slave labour abroad, they must ensure that foreign workers are not exploited in the same way. Thai workers have just received an 11 baht/day (9 baht in some provinces) increase in the minimum wage, with a 3% increase in basic commodities. This is contrary to the Thai Labour Council's request to the Commerce Ministry to control the price of goods if the daily minimum wage increase of 10 baht was agreed to. They are presently lobbying for the revival of labour unions in state enterprise and for an improvement in workplace safety. The wage rise does not apply to the agriculture, fisheries, forestry, livestock raising and others specified by the Interior Ministry. These are the areas in which most of the Burmese illegal immigrants are to be employed. Labour groups argue that 'aliens' would take away local jobs as they demand lower wages. It is arguable that there is no 'demand' for lower wages, simply that the illegal workers are vulnerable to unscrupulous employers' demands that they be paid less and know that they must accept without question what is given, knowing they have no recourse to obtain more. Sources: BP TN 960502,960506, 960608, 960612, 960620, 960701,960703, 960712, 960729, 960731, 960802, 960809 960604, 960626, 960725, 960804

August 1996 7

IN THE NEWS

NEWS BRIEFS

alaysian activists, from 16 NGOs, condemned their government for hosting a 5 day state visit by Burma's military leader, General Than Shwe. General Than Shwe, Planning Minister, Brigadier-General David Abel, Information Minister, Major-General Aye Kyaw and a 48 member delegation arrived to a full ceremonial welcome, led by the Malaysian king. BP 960814

hones Shake Economy: In mid July SLORC began selling 4,000 mobile phones for US$4,000 each. The phone sales drained a considerable amount of currencyfromthe market and in three days dvaluai the kyat from L45 to 180 to the dollar. As a result, prices of imports has risen. By the end of July the exchange rate had stabilized again around 150 kyattothe dollar. BP960717 FEER960815

-8-% Protests: In commmoration of the 8-8-88 massacres, students in Bangkok, Tokyo, Australia, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany and France organized protests outside Burmese embassies. Students in Bangkok smeared blood on the embassy's outer wall, while students in Tokyo organized a 36-hour hunger strike. TN960809 BP960809

ttacks by the lesser grain borer and grain moth have wiped out as much as 85% ofricein storage in Burma, alarming farmers who have not faced such infestations in their lifetimes. Rice exports have plunged. Farm exports are the biggest revenue earner for the state, says the World Bank, which is critical for pulling Burma from the ranks of the world's poorest nations. BP 960814

IV/AIDS: On Aug. 13, Article 19 claimed that a lack of education, statistics and reports coupled with the SLORC's refusal to grant entry to NGOs has created an unchecked HIV/AIDS epidemic. While the official gov ernment figure stands at 9,885 cases, the World Health Organization estimates that there are closer to 500,000 infected individuals in Burma TN960813 BP960814

he US embassy in Rangoon released a report on Burma, which SLORC has sharply criticised because it didn't use official statistics. The report indicates a rising debt, poor infrastructure, human rights violations, high military budget and poor education and health systems. TN960804 BP960807 Foreign Economic Trends Report: Burma

Burma Issues PO Box 1076 Silom Post Office Bangkok 10504 THAILAND

1 1 1

ADDRESS CORRECTION REQUESTED

AIR MAIL

3 August 1996

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Karen People of BurmaDocument18 paginiThe Karen People of Burmaladyt3mpl4rÎncă nu există evaluări

- A .G.T. I Donation List 2010-SingaporeDocument16 paginiA .G.T. I Donation List 2010-SingaporemgluayeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Economist (20210417) - CalibreDocument226 paginiThe Economist (20210417) - CalibreMd. Sazzad HossainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burmaissues: Humanity at The CentreDocument8 paginiBurmaissues: Humanity at The CentreKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organization Can Change A Whole Society," Aung San Su Kyi in A 14 May 1999 Interview Stating That The DireDocument8 paginiOrganization Can Change A Whole Society," Aung San Su Kyi in A 14 May 1999 Interview Stating That The DireKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal 11Document3 paginiJournal 11Vivian Guillermo CasilÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09 - The Role of Peoples OrganizationsDocument16 pagini09 - The Role of Peoples OrganizationsGracia EmbudoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Is It Important To Study Politics? How Is This Relevant To Your Career and To Your National Identity?Document4 paginiWhy Is It Important To Study Politics? How Is This Relevant To Your Career and To Your National Identity?Llora Jane GuillermoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burmaissues: Burma: Relations With Regional Communities, Bangkok, 25 Aug 1998Document8 paginiBurmaissues: Burma: Relations With Regional Communities, Bangkok, 25 Aug 1998Kyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peñaflor - Polsc 101 Thy-1 - Reflection Paper 1Document3 paginiPeñaflor - Polsc 101 Thy-1 - Reflection Paper 1Jarod Landrix PeñaflorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ngo UasDocument5 paginiNgo UasNathália Melissa PereiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feranil, Melanie - Midterm Exam - Political DynamicsDocument3 paginiFeranil, Melanie - Midterm Exam - Political DynamicsHanchey ElipseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mechanisms and Procedures for a Political ActionDe la EverandMechanisms and Procedures for a Political ActionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Dynasties in The PhilippinesDocument5 paginiPolitical Dynasties in The PhilippinesmoneybymachinesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pakistan Studies AssignmentDocument6 paginiPakistan Studies AssignmentZarak KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4POL1 PANGILINAN JoseMari BlogNumber1Document5 pagini4POL1 PANGILINAN JoseMari BlogNumber1Jose Mari PangilinanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Consciousness Perpetual Quest Valarie MillerDocument4 paginiPolitical Consciousness Perpetual Quest Valarie MillerKristine Camille Sadicon MorillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Democratic Deficits in The Phils - What Is To Be DoneDocument232 paginiDemocratic Deficits in The Phils - What Is To Be DoneDennis Montemayor LalataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Politics, Economics, and Pluralism ParticipationDocument7 paginiPolitics, Economics, and Pluralism ParticipationNaushaba ParveenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Democracy and Illiteracy Cannot Move TogetherDocument6 paginiDemocracy and Illiteracy Cannot Move Togethergodic100% (2)

- PPG SubjectDocument18 paginiPPG SubjectClanther John RiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparison of Indian and American Pressure GroupsDocument3 paginiComparison of Indian and American Pressure GroupsHazelnut ButterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demagogues, Populists And Their Helpers: Politics of Division, Deceit and ConflictDe la EverandDemagogues, Populists And Their Helpers: Politics of Division, Deceit and ConflictÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pressure Groups AND Public Policy: Sangeeta Bose I.R (UG-II) Class Roll: 54Document6 paginiPressure Groups AND Public Policy: Sangeeta Bose I.R (UG-II) Class Roll: 54Muskan KhatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Everyday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public LifeDe la EverandEveryday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public LifeEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Looking For Help: Will Rising Democracies Become International Democracy Supporters?Document42 paginiLooking For Help: Will Rising Democracies Become International Democracy Supporters?Carnegie Endowment for International PeaceÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dynasty PoliticsDocument9 paginiThe Dynasty PoliticsGilbert Rey CardinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical ReviewDocument8 paginiCritical Reviewapi-300155025Încă nu există evaluări

- Mabini Gianan PDFDocument38 paginiMabini Gianan PDFEmy Ruth GiananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baps3a - Abel, Rejay M. - Activity 3Document11 paginiBaps3a - Abel, Rejay M. - Activity 3SIBAYAN, WINSON OLIVERÎncă nu există evaluări

- The People On The Road To PowerDocument127 paginiThe People On The Road To PowerInformacioni SekretarijatÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Political Parties and Their Impact On Our DemocracyDocument5 paginiThe Impact of Political Parties and Their Impact On Our DemocracyKevin EspinosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument41 pagini09 - Chapter 2 PDFSRINIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Society, Conflict Resolution, and Democracy in NigeriaDe la EverandCivil Society, Conflict Resolution, and Democracy in NigeriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Democracy UpdatedDocument7 paginiDemocracy UpdatedinfinitiesauroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals FinalsDocument6 paginiFundamentals FinalsMary Margarette MontallaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BA Political ScienceDocument29 paginiBA Political Sciencesp thipathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Politics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceDe la EverandPolitics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Parties Research Paper TopicsDocument4 paginiPolitical Parties Research Paper Topicskxmwhxplg100% (1)

- Political Parties American GovernmentDocument34 paginiPolitical Parties American GovernmentJennyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes For Paty SystemDocument8 paginiNotes For Paty SystemKaye Claire EstoconingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit V - C - Can Democracies Accomodate Ethnic Nationalities - Unit 8Document40 paginiUnit V - C - Can Democracies Accomodate Ethnic Nationalities - Unit 8Arrowhead GamingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ssf1053 Introduction To Political Science Interest Groups I. Interest GroupsDocument5 paginiSsf1053 Introduction To Political Science Interest Groups I. Interest Groupskenha2000Încă nu există evaluări

- Ncert XI Political Science IntroductionDocument124 paginiNcert XI Political Science IntroductionNehal GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Quest For Peace in The PhilippinesDocument3 paginiA Quest For Peace in The PhilippinesTheresa PrudencioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 70 Governance, Administration and Development The Policy Process 71Document5 pagini70 Governance, Administration and Development The Policy Process 71Afia IsmailÎncă nu există evaluări

- Youth Participation in GovernanceDocument57 paginiYouth Participation in GovernanceRamon T. Ayco100% (15)

- ) On Armed DronesDocument4 pagini) On Armed DronesVlad SurdeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DynastyDocument3 paginiDynastyCharmaine De los ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Wrong With Political DynastiesDocument4 paginiWhat Is Wrong With Political DynastiesMichael LagundiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political DynastyDocument13 paginiPolitical DynastyKim Rabara TagordaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHILO19B SEMIFINALS SantosDocument3 paginiPHILO19B SEMIFINALS SantosJose DacanayÎncă nu există evaluări

- DaluDocument3 paginiDaluChidera OkoliÎncă nu există evaluări

- PM 201 How Are Public Policies Crafted in The PhilippinesDocument2 paginiPM 201 How Are Public Policies Crafted in The PhilippinesAlen BatoonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Society and Political Transition in AfricaDocument22 paginiCivil Society and Political Transition in AfricaestifanostzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asg Law N PoliticDocument8 paginiAsg Law N PoliticYusri MalekÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSM 1 Final PaperDocument4 paginiPSM 1 Final PaperJovey Ann FloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political DynastyDocument3 paginiPolitical DynastyVidez NdosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 NduloDocument20 pagini2 NduloMuhammad SajidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Third World NationalismDocument12 paginiThird World NationalismDayyanealosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Year in Hate & Extremism 2021Document67 paginiThe Year in Hate & Extremism 2021Allie WalkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ncgub Gets C$100,000 From Canada: Burma NewsDocument6 paginiNcgub Gets C$100,000 From Canada: Burma NewsKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burma Alert'. No.1: Hlutq W A Semb!Y) .:WJTHDocument6 paginiBurma Alert'. No.1: Hlutq W A Semb!Y) .:WJTHKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- India Myanmar Relation 2012 PDFDocument2 paginiIndia Myanmar Relation 2012 PDFKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burma News:: (Vol.2, February 1991)Document6 paginiBurma News:: (Vol.2, February 1991)Kyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burma News:: Q.1ebecDocument6 paginiBurma News:: Q.1ebecKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Salute To The People of Burma: Ham Yajr7Jghwe, Shawville, CanadaDocument4 paginiA Salute To The People of Burma: Ham Yajr7Jghwe, Shawville, CanadaKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burma Alert No.11 (November 1990)Document6 paginiBurma Alert No.11 (November 1990)Kyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- 99 NewsmDocument20 pagini99 NewsmKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ba1990 V01 N05Document6 paginiBa1990 V01 N05Kyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Published By: Ham Yawnghwe, R.R.4, Shawville, Canada JOX 2YODocument4 paginiPublished By: Ham Yawnghwe, R.R.4, Shawville, Canada JOX 2YOKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Espfedkifihtwgif Rsmrsdwif Aemuwjh Jynfolrsm Tcsif Csif Cspfmunf&If Esd Qufqhri Cdkifnrjpgmwnfwhhusef&Pfaezdky Ta& BudDocument20 paginiEspfedkifihtwgif Rsmrsdwif Aemuwjh Jynfolrsm Tcsif Csif Cspfmunf&If Esd Qufqhri Cdkifnrjpgmwnfwhhusef&Pfaezdky Ta& BudKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jrefrmedkifihrsm Edkifiha& T& WDK Wufjzpfxgef Ri (M Vlytzgjutpnf &jy Edkifiha& Kpfusufoa&Udk JR Ifhwifjcif JZPFDocument20 paginiJrefrmedkifihrsm Edkifiha& T& WDK Wufjzpfxgef Ri (M Vlytzgjutpnf &jy Edkifiha& Kpfusufoa&Udk JR Ifhwifjcif JZPFKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- 109 NewsmDocument20 pagini109 NewsmKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- 110 NewsmDocument20 pagini110 NewsmKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zawwin, Ne Win'S Son-In-Law (F8912141Document8 paginiZawwin, Ne Win'S Son-In-Law (F8912141Kyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Myanmar: Update On Political Arrests and TrialsDocument12 paginiMyanmar: Update On Political Arrests and TrialsKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Myanmar: Human Rights Violations Against Ethnic MinoritiesDocument13 paginiMyanmar: Human Rights Violations Against Ethnic MinoritiesKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amnesty International: MyanmarDocument11 paginiAmnesty International: MyanmarKyaw NaingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kachintodayusa.2009.January JuneDocument134 paginiKachintodayusa.2009.January JuneJingphawÎncă nu există evaluări

- LNGOs Contact AddressesDocument14 paginiLNGOs Contact Addressesapi-3799289Încă nu există evaluări

- Chin StateDocument11 paginiChin StateLTTuangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Birth Registration and Citizenship in ThailandDocument174 paginiBirth Registration and Citizenship in ThailandPugh Jutta100% (1)

- The Daily Star On 10.07.2020Document12 paginiThe Daily Star On 10.07.2020shafikulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Character Traits and Values of MyanmarDocument3 paginiCharacter Traits and Values of MyanmarkakayÎncă nu există evaluări

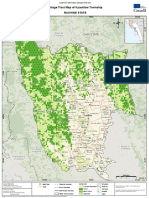

- VT Map Kyauktaw TSP Rakhine MIMU224v02 04apr2017 A3 0Document1 paginăVT Map Kyauktaw TSP Rakhine MIMU224v02 04apr2017 A3 0Min Khine TheinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burma Army Tracks Across Shan State EnglishDocument4 paginiBurma Army Tracks Across Shan State EnglishPugh JuttaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief History of MyanmarDocument3 paginiA Brief History of MyanmarNicholas KuekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music of MyanmarDocument7 paginiMusic of MyanmarHeaven2012Încă nu există evaluări

- Monday, May 25, 2015 (Daily Issue 49)Document26 paginiMonday, May 25, 2015 (Daily Issue 49)The Myanmar TimesÎncă nu există evaluări

- TigerDocument4 paginiTigerHarunzz AbdullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- 201438742Document68 pagini201438742The Myanmar TimesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Latest 1674731647Document12 paginiLatest 1674731647Nandar AungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burma (Myanmar Presentation)Document26 paginiBurma (Myanmar Presentation)Sa Sai Noah100% (1)

- Divya A. Jain: Name of AuthorDocument11 paginiDivya A. Jain: Name of AuthorkomalÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCEA PresentationDocument21 paginiMCEA Presentationachopra14Încă nu există evaluări

- Simple FileDocument2 paginiSimple Filedraftdelete101 errorÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Shan State - From Its Origin To 1962Document5 paginiHistory of Shan State - From Its Origin To 1962RobertÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salai Tin Maung OoDocument8 paginiSalai Tin Maung OoRobert Sanga HualngoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Myanmar National Qualifications FrameworkDocument6 paginiMyanmar National Qualifications Frameworkkyishwin100% (5)

- MyanmarDocument1 paginăMyanmarMgZayar2288Încă nu există evaluări

- Myanmar: Rice ExportDocument88 paginiMyanmar: Rice Exportericaalini100% (1)

- RohingyaIdentityCrisisACaseStudy PDFDocument7 paginiRohingyaIdentityCrisisACaseStudy PDFHarikrishnan GÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Management in MyanmarDocument24 paginiWater Management in Myanmarwilbar1100% (1)

- Ant Bwe Kyaw 2 July 2009Document4 paginiAnt Bwe Kyaw 2 July 2009Aung Myo TheinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Myanmar: Pharma ProfileDocument26 paginiMyanmar: Pharma Profilejbundela100% (8)