Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

03 Stump e Fischer, Transfer Principle and Moral Responsability (PP 47-55)

Încărcat de

michelezanellaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

03 Stump e Fischer, Transfer Principle and Moral Responsability (PP 47-55)

Încărcat de

michelezanellaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Transfer Principles and Moral Responsibility Author(s): Eleonore Stump and John Martin Fischer Source: Nos, Vol.

34, Supplement: Philosophical Perspectives, 14, Action and Freedom (2000), pp. 47-55 Published by: Blackwell Publishing Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2676121 . Accessed: 12/06/2011 09:07

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Blackwell Publishing is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Nos.

http://www.jstor.org

Philosophical Perspectives, Actionand Freedom, 14, 2000

TRANSFER PRINCIPLES AND MORAL RESPONSIBILITY

Eleonore Stump Saint Louis University John Martin Fischer University of California, Riverside

It is useful to divide contemporaryarguments for the incompatibility of causal determinismand moral responsibility into two types: indirect and direct. The indirect argumentspresent reasons why causal determinismis incompatible with the possession of the relevant kind of alternativepossibilities and conclude from this thatcausal determinismis incompatiblewith moralresponsibility. It is, of course, a presuppositionof the indirect argumentsthat moral responsibility requires alternative possibilities. The direct arguments contain no such presupposition, although some of their proponents may believe that moral responsibility does indeed require alternativepossibilities. The direct argumentsemploy what might be called "transfer"principles. These are principles that transfera certain property;the relevant propertyhere is lack of moral responsibility.l "Np" abbreviate "p and no one is even Let partly morally responsible for the fact that p." Then this is a transferprinciple introducedby Peter van Inwagen: Rule B: Np and N(p

>

q) implies Nq.2

Van Inwagen's Rule B is a transferprinciple insofar as it transfersthe property of lack of moral responsibility from one fact to anotherby the medium of lack of responsibility for the pertinent conditional. Van Inwagen's direct argumentfor the incompatibility of causal determinism and moral responsibility can be presented simply as follows. For present purposes, we can understandcausal determinism as the doctrine that a complete descriptionof the (temporallynonrelational)state of the universe at a time, and a description of the laws of nature, entail every truth about subsequent times. Let P be a proposition describing the state of the universe before there were any human beings, let L be a proposition describing the laws of nature,

48 / Eleonore Stump and John Martin Fischer

lSm 1S

and let F be a truthabout the way the world is today Then, if causal determintrue,

. .

(1) (PandL>F). Clearly, no one is even partly morally responsible for this fact, and so this is also true: (2) N[(P and L) Since [(P and L)

> >

F].

>

F] is equivalent to [P > (L

F)], this is true as well:

(3) N[P'(L'F)] Now (4) NP, and so by Rule B, from (3) and (4) we can conclude (5) N(L Since (6) NL, by anotherapplication of Rule B, from (5) and (6) we reach the conclusion, (7) NF. truth,this conclusion can be generalized. Consequently, Since F is an arbitrary the argumentappearsto show in a direct fashion that if causal determinismis true, no one is even in part morally responsible for any fact. But Rule B can be called into question. Mark Ravizza offers the following kind of case to impugn Rule B.3 At T1, Betty freely detonates explosives as part of a plan to start an avalanche that will destroy an enemy camp; and, in fact, her explosion does succeed in causing an avalanche that is sufficient to destroy the camp at T3. Unbeknown to Betty, however, there is anothercause of the camp s destruction by avalanche. At T1, a goat kicks loose a boulder, and it causes an avalanche which is also sufficient to destroy the camp at T3 and which contributesto the actual destructionof the camp at T3. In the story, no one is even partly morally responsible for the goat s kicking the boulder. And no one is even partly morally responsible for the fact that if the goat kicks that boulder at T1, then the camp is destroyedby avalanche at T3. Nonetheless,

>

F).

TransferPrinciples / 49

Betty is at least partly responsible for the camp's being destroyedby avalanche at T3. Thus, Ravizza's case apparentlyshows that Rule B is invalid. In cases of simultaneous causation, the rule fails.4 In a recent paper,Ted Warfield has suggested a reply on behalf of the incompatibilist.5He concedes that Ravizza's case presents a challenge to Rule B. Warfield claims, however, that there is a related but non-equivalent rule he calls it 'Rule Beta [1' which can play a similar role in an argumentfor the incompatibility of causal determinism and moral responsibility. According to Warfield, Rule Beta [1 is not subject to Ravizza-style counterexamples. This is Rule Beta [1: [Np and [l(p

>

q)] implies Nq.

The key difference between Rule B and Rule Beta [1 is in the connection between p and q. For Rule B, it must be the case that if p, then q, and no one is responsible for this fact. For Rule Beta [1, the connection between p and q is one of logical necessity. Because the connection between p and q in Warfield's Rule Beta [1 is so much strongerthan the connection betweenp and q in Rule B, Warfield supposes that it will be much harder to construct scenarios which present a challenge to his rule. For Ravizza's scenario to serve as a counterexample to an inference licensed by Rule Beta [1, the connection between the goat's kicking the boulder at T1 and the camp's being destroyed by avalanche at T3 would have to be a logical one; and, of course, it is not. As Warfield says, "The conditional premise (if the goat kicks the boulder at T1, then the avalanche destroys the camp at T3), though not a propositionanyone is even partly morally responsible for, does not express a relation of logical consequence, and so Ravizza's example fails to apply to my argument [for incompatibilism]." (p.222-223) Contraryto what Warfield claims, his Rule Beta [1 is subject to Ravizzastyle counterexamples,in our view. In what follows, we present two such counterexamples, each of which is sufficient to show that Rule Beta [1 is invalid. Counterexaznple Let it be the case that, necessarily, if the actual laws of A. natureobtain and the conditions of the world at T2 (some time just before T3) are C, then there will be an avalanche that destroys the enemy camp at T3. Let it also be the case that at T1 Betty freely starts an avalanche which is sufficient to destroy the camp at T3 and which contributes to its destruction at T3. Finally, let it be the case that Betty's freely starting an avalanche is the result of some suitable indeterministicprocess. Then let r be the conjunction of (rl) the actual laws of natw-eobtain and (r2) the condition of the world at T2 is C.

50 / Eleonore Stump and John Martin Fischer

And let q be (q) there is an avalanche which destroys the enemy camp at T3. In this example, r is true. Nr is also true: nobody is even partly morally responsible for the-obtaining of the actual laws of nature and the condition of the world's being C at T2. By hypothesis, it is also true that 2(r > q). Any world in which (rl) and (r2) are true is a world in which q is true. And yet it seems clear that Nq is false. Insofar as Betty at T1 freely starts an avalanche, she is at least in part morally responsible for the camp's being destroyed by an avalanche at T3. Warfield anticipates such a case. He says, Can a Frankfurt-type (or a Ravizzaoverdetermination be constructed case case) thatis a counterexample RuleBetaC]? don'tsee how.To illustrate to I noticethat making...the avalanche logicalconsequence the goat'skickingthe boulder a of requiresthatwe assumethat [the avalanche] a deterministic is consequence the of arrangement natural of forces.Thischangewouldprovidea case thatis at leastof the rightformto serveas a counterexample RuleBeta[1. Butto be a counterexto ampleto RuleBeta [1 the examplemustbe an examplein whichthe Frankfurtian judgment moralresponsibility of [Betty'smoralresponsibility the camp'sbeing for destroyed an avalanche] by holdsup.Withthe additional assumption determinof ism thatis neededto makethecase applicable RuleBeta[1,however, Frankto this furtian judgment equivalent theclaimthatdeterminism moral is to and responsibility arecompatible. is hardly interest pointout thatthe assumption the comIt of to of patibility determinism moralresponsibility of and impliesthatRuleBeta [1 is invalid.(p.223) But note that we have not assumed causal determinism in our example. Contraryto Warfield's claim, such an assumption is not "needed to make the case applicable to [Rule] Beta [1." This is because, even in an indeterministic world, some events and states of affairs can be causally determined. One can suppose that the enemy camp's being destroyed by an avalanche at T3 is causally determinedby the goat's kicking a boulder at T1 without thereby supposing that Betty's deliberations or actions are causally determined. Even in an indeterministicworld, there can be "pockets of local determination".6 deny To this is to suppose that, for any state of affairs p whatever, the laws of nature and the condition C of the world at T2 is compatible with p at T3 and also compatible with not-p at T3. But this is to suppose that absolutely everything in the world is indeterministic,and presumablyeven libertariansdon't want to make so strong a claim. Counterexample For those still inclined to worry aboutthe issue of causal B. determinism, however, we can construct a counterexamplewhich doesn't depend on there being even local determinism.This time let r be a conjunctionof these propositions

TransferPrinciples / 51

(rl) the actual laws of natureobtain and (r3) there is an avalanche which destroys the enemy camp at T3. Now, without doubt, there is a logically necessary connection between r and q (since q is identical to [r3]), but the question of whether causal determinismof any sort obtains is irrelevant.Here we have (8) Nr and (9) [1 (r

>

q),

but it isn't the case that (10) Nq, for the sort of reasons given in connection with Ravizza's story. Warfield has an objection to this sort of counterexample, too. He maintains that (W1) if no one is even partly morally responsible for a conjunction, then no one is even partly morally responsible for either conjunct of the conjunction. (p.218)7 This claim calls into question Nr in our counterexampleB. It is not the case that no one is even partly responsible for (r3). On (W1), then, it isn't the case that no one is even partly morally responsible for r. Consequently,Nr is false. But is Warfield's claim (W1) right? We think it isn't, because of the connection between conjunctions and conditionals. To see this, consider again Ravizza's story. It is not the case that if the actual laws of nature obtain, there will not be an avalanche that destroys the enemy camp at T3. So this is true: (11) not (L > not-q). Furthermore,it seems odd to think that anyone is even partly responsible for (1 1). It is peculiar to suppose that a humanbeing is to blame for (1 1), is the

52 / Eleonore Stump and John Martin Fischer

source of the state of affairs described by (11), could have broughtit about that that state of affairs didn't obtain, and so on. So this also seems true: (12) N[not (L > not-q)]. Of course, (11) is equivalent to this: (13) (L and q). So it seems as if this also has to be true: (14) N(L and q).8 But now we have a problem, if (W1) is correct. In Ravizza's story, Betty is partly responsible for q. Therefore, it isn't true that no one is even partly responsible for the conjuncts of (13); Betty is at least partly responsible for q. On (W1), however, for it to be the case that no one is even partly responsible for the conjunction, it would also have to be the case that no one was even partly responsible for either of the conjuncts. Consequently,if Warfield's claim (W1) is true, (14) isfalse. In that case, however, Warfield must also hold that (12) is false. But the claim that (12) is false strikes us as counter-intuitive. Furthermore, the preceding discussion shows, if (W1) is true, so is this: as (W2) Given a true antecedent of a conditional,9a person is partly responsible for the conditional's being false if he is partly responsible for the falsity of the consequent of the conditional. I0 That's why commitment to (W1) turns out to requirerejecting (12) N[not (L

>

not-q)].

But if (W2) is true, it seems that this ought also to be true: (W3) Given a true antecedent of a conditional, a person is partly responsible for the conditional's being true if he is partly responsible for the truthof the consequent of the conditional. Why should we accept that a person is partly responsible for the falsity of a conditional with a true antecedent because of his responsibility for the falsity of the consequent, and yet deny that a person is partly responsible for the truth of a conditional with a true antecedent because of his responsibility for the truthof the consequent?

TransferPrinciples / 53

Another way to see the connection between (W1) and (W3) is to consider the reason Warfield gives for accepting (W1). To make (W1) seem plausible, Warfield says, "being at least partly morally responsible for a conjunct is a way of being partly morally responsible for a conjunction"(p.218). But if that is right, then it seems that a similar point ought to apply to conditionals: being partly responsible for the truth of the consequent of a conditional with a true antecedentis a way of being partly responsible for the truthof the conditional. And yet (W3) is clearly mistaken. To see this, consider (9) again:

(9)

g (r > q),

where r is (rl) the actual laws of natureobtain, and (r3) there is an avalanche which destroys the enemy camp at T3, and q is identical to (r3). Warfield also accepts this rule of inference, taken from Peter van Inwagen: Rule A: [1 p implies Np. Rule A seems entirely uncontroversial.In fact, Warfield says, van Inwagen's Rule A is (nearly) as trivial and inconsequentialas a rule of inference could be. No one has, to my knowledge, challenged this principle nor has anyone challenged any principle closely related to Rule A.l l Now, from (9), by Rule A, we get (15) N (r

> q).

On (W3), however, a person is partly responsible for the truthof a conditional with a true antecedent if she is partly responsible for the truth of the consequent of the conditional. So, on (W3), we will have to say that (15) is false, just as (12) is, because Betty is partly responsible for q. By Rule A, however, it then follows that (9) is false, since by Rule A (9) implies (15). Without doubt, this is absurd.So either Rule A is after all invalid, or (W3) is false. And if (W3) is false, then by parity of reasoning it seems that (W1) is false also. For these reasons, we think Warfield's claim (W1) should be rejected. The logic of responsibility is more complicated than (W1) implies. Given the rela-

54 / Eleonore Stump and John Martin Fischer

tion between conjunctions and conditionals, it is right to hold that someone can be partly responsible for a conjunct of a conjunction without being partly responsible for the conjunction. Consequently,our counterexampleB is also effective against Rule Beta [1. Finally, we think it is worth pointing out that one of us believes that causal determinismis incompatible with moral responsibility and the other does not. But we unite in thinking that causal determinismcannot be proved incompatible with moral responsibility by Warfield's Rule Beta 2.12 Notes 1. In the contextof the indirect arguments the incompatibility causaldeterminfor of ism andmoralresponsibility, can have"Transfer Powerlessness" one of principles. For a discussion such principles, JohnMartinFischer,The Metaphysics of of see Free Will:An Essay on Control, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1994),pp.23-66. 2. PetervanInwagen, Essay on Free Will, (Oxford: An Clarendon Press,1983),p.184. 3. MarkRavizza,"Semi-Compatibilism the Transfer Nonresponsibility," and of Philosophical Studies 75 (1994), pp.61-93, esp. p.78. For similarexamples,see also JohnMartinFischerand MarkRavizza,Responsibility and Control: A Theory of Moral Responsibility,(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1998),pp.151-169. 4. Oneof us (Stump), nottheother, but thinks isn'tclearthattheinvalidity RuleB it of shownby Ravizza's example renders Inwagen's Van argument irremediably invalid. Thatis because RuleB fails only in certain cases,andit isn'tclearto one of us that casesof moralresponsibility be assimilated thosecasesof simultaneous can to causationin whichRuleB fails. 5. TedA. Warfield, "Determinism MoralResponsibility Incompatible," and Are Philosophical Topics 24 (1996),pp.215-226.In addition the suggestion to explored in the text, Warfield also presents otherstrategies replyingto the compatibilistic for strategy Ravizza; especially, of see, pp.221-222. Subsequent references Warfield's to paperwill be givenby pagenumber parentheses the text. in in 6. DanielDennett introduces term'localfatalism' referto a related different the to but notion: DanielC. Dennett, Elbow Room: The Varietiesof Free Will WorthWanting, (Cambridge, Mass.andLondon: MITPress,1984),pp.104-106. 7. Onepossiblereasonfor thinking (W1) is trueis the supposition one is at that that leastpartlymorally responsible a conjunction one is morally for if responsible a for partof a conjunction. beingmorally But responsible a partof a conjunction for and being partlymorallyresponsible a conjunction not the same thing,as our for are argument whatfollowshelpsto makeclear. in 8. This inference licensedby the fact thatif p andq are logicallyequivalent, is then Np if andonly if Nq. 9. It's possibleto interpret (W1) as applying only to trueconjunctions; thatcase, in this qualification (W2) is needed. in 10. Obviously, canswitchtheconjuncts theconjunction we in from(L andq) to (q and L), whichis equivalent to

(128) not (q

>

not-L).

TransferPrinciples / 55 Since Betty is partly responsible for (q and L), she will also be partly responsible for (128). Consequently,accepting (W1) requires accepting not only (W2) but also (W2*) Given a false consequent, a person is partly responsible for a conditional's being false if he is partly responsible for the truthof the antecedent of the conditional. 11. Pp.218-219. Similarly, Van Inwagen says, "The validity of Rule (A) seems to me to be beyond dispute. No one is responsible for the fact that 49 x 18 = 882, for the fact that arithmeticis essentially incomplete, or, if Kripke is right about necessary truth,for the fact that the atomic numberof gold is 79." (Van Inwagen 1983, p.184). 12. We are grateful to David Widerker,Al Mele, Chris Pliatska, and Ted Warfield for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Dion C. Smythe (Ed) - Strangers To Themselves - The Byzantine Outsider (Society For The Promotion of Byzantine Studies - 8) - Ashgate (2000) PDFDocument279 paginiDion C. Smythe (Ed) - Strangers To Themselves - The Byzantine Outsider (Society For The Promotion of Byzantine Studies - 8) - Ashgate (2000) PDFmichelezanellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carruthers - The Illusion of Conscious Will PDFDocument17 paginiCarruthers - The Illusion of Conscious Will PDFmichelezanellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 Widerker, Frankfurt - S Attack On The Principle of Alternative Possibilities (181-201)Document22 pagini10 Widerker, Frankfurt - S Attack On The Principle of Alternative Possibilities (181-201)michelezanellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 07 Pereboom, Alternative Possibilities and Causal Histories (119-137)Document20 pagini07 Pereboom, Alternative Possibilities and Causal Histories (119-137)michelezanellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12 Zagzegbski, Does Libertarian Freedom Require Alternate Possibilities (231-248)Document19 pagini12 Zagzegbski, Does Libertarian Freedom Require Alternate Possibilities (231-248)michelezanellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 04 Kane, The Dual Regress of Free Will and The Role of Alternative Possibilities (PP 57-79)Document24 pagini04 Kane, The Dual Regress of Free Will and The Role of Alternative Possibilities (PP 57-79)michelezanellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Canon in D) Easy PianoDocument2 pagini(Canon in D) Easy Pianoluiscovar1166100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Fakeaway - Healthy Home-Cooked Takeaway MealsDocument194 paginiFakeaway - Healthy Home-Cooked Takeaway MealsBiên Nguyễn HữuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plant Seedling Classification Using CNNDocument12 paginiPlant Seedling Classification Using CNNYugal Joshi0% (1)

- Satellite Communication Uplink Transmitter Downlink Receiver and TransponderDocument2 paginiSatellite Communication Uplink Transmitter Downlink Receiver and TransponderTHONTARADYA CHANNELÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tajima Usb Linker User's GuideDocument35 paginiTajima Usb Linker User's GuideFermin MuñozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solving Problems Involving Kinds of Propotion StudentDocument18 paginiSolving Problems Involving Kinds of Propotion StudentJohn Daniel BerdosÎncă nu există evaluări

- English 6 Action Research Contextualized Materials ProposalDocument41 paginiEnglish 6 Action Research Contextualized Materials ProposalJake YaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The UFO MonthlyDocument21 paginiThe UFO MonthlySAB78Încă nu există evaluări

- Renal Cortical CystDocument2 paginiRenal Cortical Cystra222j239Încă nu există evaluări

- ABRACON's Tuning Fork Crystals and Oscillators for 32.768kHz RTC ApplicationsDocument13 paginiABRACON's Tuning Fork Crystals and Oscillators for 32.768kHz RTC Applicationsdit277Încă nu există evaluări

- Lynn Waterhouse - Critique On Multiple IntelligenceDocument20 paginiLynn Waterhouse - Critique On Multiple IntelligencenkrontirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mibk - TDS PDFDocument3 paginiMibk - TDS PDFMardianus U. RihiÎncă nu există evaluări

- MSE Admission and Degree RequirementsDocument6 paginiMSE Admission and Degree Requirementsdeathbuddy_87Încă nu există evaluări

- Got 1000 Connect To Alpha 2Document42 paginiGot 1000 Connect To Alpha 2supriyo110Încă nu există evaluări

- Water Demand Fire Flow Calculation Hydraulic ModelingDocument110 paginiWater Demand Fire Flow Calculation Hydraulic ModelingArthur DeiparineÎncă nu există evaluări

- RUDDER PLATING DIAGRAMDocument1 paginăRUDDER PLATING DIAGRAMMuhammad Ilham AlfiansyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sir ClanDocument109 paginiSir ClanJames AbendanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2003 VW Jetta Wiring DiagramsDocument123 pagini2003 VW Jetta Wiring DiagramsmikeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Law Handbook ExampleDocument20 paginiEnvironmental Law Handbook ExampleThomson Reuters Australia100% (5)

- Design of Goods & Services: Tanweer Ascem KharralDocument10 paginiDesign of Goods & Services: Tanweer Ascem KharralHadeed GulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sri Lanka's Mineral Resources Can Enrich Country's CoffersDocument139 paginiSri Lanka's Mineral Resources Can Enrich Country's CoffersPrashan Francis100% (3)

- Tivax STB-T12 Owners ManualDocument32 paginiTivax STB-T12 Owners ManualJesseÎncă nu există evaluări

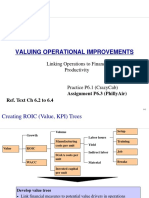

- 2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityDocument14 pagini2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityAidan HonnoldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chips Unlimited Blend LibraryDocument20 paginiChips Unlimited Blend Librarymizan sallehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adept Conveyor Technologies Product ManualDocument32 paginiAdept Conveyor Technologies Product ManualBagus Eko BudiyudhantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- D5293Document8 paginiD5293Carlos Olivares ZegarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intelligence, Reasoning, Creativity, and WisdomDocument3 paginiIntelligence, Reasoning, Creativity, and WisdomSammy DeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Britain Had Christianity EarlyDocument47 paginiWhy Britain Had Christianity EarlyChris WoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2G Call FlowDocument71 pagini2G Call Flowm191084Încă nu există evaluări

- Kalpana ChawlaDocument5 paginiKalpana Chawlanoor.md100% (2)

- Explore the Precambrian EraDocument3 paginiExplore the Precambrian EraArjay CarolinoÎncă nu există evaluări