Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Încărcat de

agoyal_9Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Încărcat de

agoyal_9Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

w79

08.18.09

Residents Section Pat tern of the Month

Bubbly Lesions of Bone Eisenberg Residents Section Pattern of the Month

Residents

inRadiology

Ronald L. Eisenberg1

Eisenberg RL

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

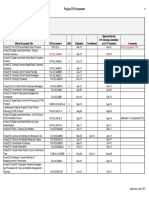

Bubbly lesions of bone are common findings on skeletal radiographs. The long, otherwise difficult-to-recall differential diagnosis has led to the development of the classic mnemonic fegnomashic, which some have preferred to rearrange as fog machines. The entities in the following list account for more than 95% of the conditions that produce bubbly lesions of bone:

Fegnomashic

Fibrous dysplasia Enchondroma Eosinophilic granuloma Giant cell tumor Nonossifying fibroma Osteoblastoma Metastases Myeloma Aneursymal bone cyst Simple bone cyst Hyperparathyroidism (brown tumor) Infection Chondroblastoma Chondromyxoid fibroma

Keywords: bubbly lesions, fegnomashic, skeletal radiograph DOI:10. 2214/AJR.09.2964 Received April 27, 2009; accepted after revision May 1, 2009.

1 Department of Radiology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215. Address correspondence to R. L. Eisenberg (rleisenb@ bidmc.harvard.edu).

WEB This is a Web exclusive article. AJR 2009; 193:W79W94 0361803X/09/1932W79 American Roentgen Ray Society

A

Fig. 1Fibrous dysplasia. Views of humerus (A) and ischium (B) in two different patients show expansile lesions containing irregular bands of sclerosis, giving them multilocular appearance.

AJR:193, August 2009

W79

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia (Fig. 1) is a proliferation of fibrous tissues in the medullary cavity, usually beginning during childhood. Involving a single bone in 7080% of cases, fibrous dysplasia most commonly affects the long bones (femur, tibia), ribs, and skull. It is the most common cause of an expansile focal rib lesion. Fibrous dysplasia is associated with endocrinopathy in 23% of patients, especially in girls who experience precocious puberty. Malignant degeneration is extremely rare. Fibrous dysplasia appears radiographically as a well-defined lucent area, which varies from completely radiolucent to homogeneous ground-glass density depending on the amount of fibrous or osseous tissue deposited in the medullary cavity. Often there is local expansion of bone with endosteal erosion of the cortex that predisposes to pathologic fractures. In severe and long-standing disease, affected bones may be bowed or deformed (shepherds crook deformity of the femur).

Enchondroma

Enchondroma (Figs. 2 and 3) is a common benign cartilaginous tumor that is most frequently found in children and young adults. It is usually asymptomatic and discovered either incidentally or when a pathologic fracture occurs. The development of severe pain or radiographic growth of the lesion with loss of marginal definition, cortical disruption, and local periosteal reaction suggests malignant degeneration. The incidence of this complication increases the closer the tumor is to the axial skeleton. Multiple enchondromatosis is termed Olliers disease. Typically involving a small bone of the hands and feet, an enchondroma appears radiographically as a well-marginated lucency arising in the medullary cavity, usually near the epiphysis. It expands bone locally and often causes thinning and endosteal scalloping of the cortex. This may lead to pathologic fracture with minimal trauma. Characteristic calcifications, which may vary from minimal stippling to large, amorphous areas of increased density, develop in the lucent matrix.

A

Fig. 2Enchondroma. A, Well-demarcated tumor (arrow) expands bone and thins cortex. B, Pathologic fracture (arrow).

W80

AJR:193, August 2009

w79

08.18.09

Eisenberg

Fig. 3Multiple enchondromatosis. View of both hands shows multiple globular and expansile lucent filling defects involving all metacarpals and proximal and middle phalanges.

Eosinophilic Granuloma

Eosinophilic granuloma (Fig. 4) is the benign form of Langerhans histiocytosis that predominantly affects the skull, pelvis, femur, and spine. This condition almost always occurs before 30 years of age and most affected patients are under 20. Eosinophilic granuloma usually appears radiographically as a well-defined medullary lucency, often with endosteal scalloping and local or extensive periosteal reaction. Rapidly growing lesions may have indistinct,

Fig. 4Eosinophilic granuloma. Bubbly osteolytic lesion in femur, with scalloping of endosteal margins and thin layer of periosteal response.

AJR:193, August 2009

W81

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Fig. 5Giant cell tumor. Typical eccentric lucent lesion in distal femoral metaphysis extends to immediate subarticular cortex. Surrounding cortex, though thinned, remains intact.

Fig. 6Malignant giant cell tumor. Tumor has caused cortical disruption, extends outside host bone, and has ill-defined margin.

hazy borders. A characteristic finding is a peculiar beveled contour of the lesion that produces a hole-within-a-hole effect. In the skull, eosinophilic granuloma typically produces one or more small punched-out areas that originate in the diploic space, expand and perforate both the inner and outer tables, and often contain a central bone density (button sequestrum). In the spine, generally spotty destruction in a vertebral body may proceed to collapse the vertebra into a thin flat disk (vertebra plana).

Giant Cell Tumor

Giant cell tumor (Figs. 5 and 6) is a lytic lesion that develops in the end of a long bone of a young adult after epiphyseal closure. It primarily involves the knee (distal femur, proximal tibia) and wrist (distal radius, ulna). Although usually asymptomatic, a giant cell tumor may be associated with intermittent dull pain and a palpable tender mass and predispose to pathologic fracture. Approximately 20% of giant cell tumors are malignant, although there is much overlap in the radiographic appearance of benign and malignant lesions. The malignant nature of a lesion is best seen as tumor extension through the cortex and an associated soft-tissue mass on CT. Giant cell tumor classically appears radiographically as an eccentric lucent metaphyseal lesion that may extend to the immediate subarticular cortex of a bone but does not involve the joint. Expansion toward the shaft produces a well-demarcated lucency, often with cortical expansion but without a sclerotic shell or border. Aggressive lesions cause cortical destruction, though this can be seen in benign lesions.

Nonossifying Fibroma

A nonossifying fibroma (Fig. 7) results from a fibrous cortical defect (discussed later), a common process that develops in up to 40% of normal children. Although most of these defects regress spontaneously and disappear by the time of epiphyseal closure, a persistent and growing lesion with continued proliferative activity in an older child or young adult is termed a nonossifying fibroma. The lesion most frequently occurs in the distal portions of the femur and tibia. A nonossifying fibroma appears radiographically as a multilocular, eccentric lucency that causes cortical thinning and expansion. It generally is sharply demarcated by a thin, scalloped rim of sclerosis.

W82

AJR:193, August 2009

w79

08.18.09

Eisenberg

Fig. 7Nonossifying fibroma. Multilocular, eccentric lucency with sclerotic rim in distal femur.

Osteoblastoma

Osteoblastoma (Figs. 8 and 9) is a rare bone neoplasm that most often arises in adolescence. Approximately one half involve the vertebral column, most frequently the posterior elements (neural arches and processes). Most of the remainder of these neoplasms affect the long bones or the small bones of the hands and feet. Although predominantly lytic, an osteoblastoma occasionally has internal calcification and an aggressive appearance simulating a malignant lesion. It may be difficult to differentiate histologically from an osteoid osteoma, but it is usually much larger (> 2 cm) and thus the term giant osteoid osteoma is often applied to the sclerotic form of this lesion. An osteoblastoma usually appears radiographically as a well-circumscribed, eccentric, and expansile lucency. It may break through the cortex to produce a soft-tissue component surrounded by a thin calcific shell.

Fig. 8Osteoblsatoma. Sharply defined erosive lesion (arrows) involves superior margin of lower cervical spinous process.

Fig. 9Osteoblastoma. Expansile, eccentric mass in proximal humerus causes thinning of cortex (arrows).

AJR:193, August 2009

W83

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

A

Fig. 10Metastasis (lung cancer). Frontal (A) and lateral (B) views show large, purely lytic lesion with substantial soft-tissue component. (Courtesy of Jim Wu, Boston, MA)

Fig. 11Metastasis (thyroid carcinoma). Large area of entirely lytic, expansile destruction (arrows) involves left ilium.

Metastases

Most lytic metastases (Figs. 10 and 11) are irregular, poorly defined, and multiple. However, a single large metastatic focus may occasionally appear as an expansile, trabeculated lesion. Termed a blowout metastasis, it typically is secondary to a highly vascular carcinoma of the kidney or thyroid.

Myeloma

A single plasma cell tumor (Fig. 12) may infrequently present as an apparently solitary destructive bone lesion with no evidence of the major disease complications usually associated with multiple myeloma. It generally develops into typical multiple myeloma (diffuse lytic lesions) within 12 years (Fig. 13). A solitary plasmacytoma typically appears radiographically as an expansile, often trabeculated lucency that predominantly involves the ribs, long bones, and pelvis. A highly destructive tumor may expand or balloon bone before it breaks through the cortex. In the spine, an affected vertebral body may collapse or be destroyed.

W84

AJR:193, August 2009

w79

08.18.09

Eisenberg

A

Fig. 12Myeloma. Frontal views (A and B) of both femurs show multiple small lytic lesions. (Courtesy of Jim Wu, Boston, MA)

Fig. 13Myeloma (solitary plasmacytoma). Highly destructive tumor has obliterated virtually entire left half of pelvis.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

Rather than a true neoplasm or cyst, an aneurysmal bone cyst (Fig. 14) is composed of numerous blood-filled arteriovenous communications. It most frequently occurs in children and young adults, presenting with mild pain of several months duration, swelling, and restriction of movement. Aneurysmal bone cysts primarily involve the metaphyses of long bones (especially the femur and tibia) and the posterior elements of vertebrae. The lesion may extend beyond the axis of the host bone and form a visible soft-tissue mass that, when combined with a cortex so thin that it is invisible on radiographs, may be mistaken for a malignant bone tumor. An aneurysmal bone cyst appears radiographically as an expansile, eccentric, cystlike lesion causing marked ballooning of thinned cortex. Light trabeculation and septation in the lesion may produce a multiloculated appearance. Periosteal reaction may develop.

AJR:193, August 2009

W85

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Fig. 14Aneurysmal bone cyst. Expansile, eccentric, cystic lesion of tibia with multiple fine internal septa. Because severely thinned cortex is difficult to detect, tumor resembles malignant process.

Fig. 15Simple bone cyst. Lesion in proximal humerus has oval configuration, with its long axis parallel to that of host bone. Note thin septa that produce multiloculated appearance.

Simple Bone Cyst

A simple bone cyst (Figs. 15 and 16) is a true fluid-filled cyst with a wall of fibrous tissue. It begins adjacent to the epiphyseal plate and appears to migrate down the shaft, although in reality it is the epiphysis that has migrated away from the cyst. Bone cysts arise in children and adolescents and most commonly involve the proximal humerus and femur. They often present as a pathologic fracture, which may show the fallen fragment sign (fragments of cortical bone that are free to fall to the dependent portion of the fluid-filled cyst, unlike a bone tumor that has a firm tissue consistency). Radiographically, a simple bone cyst appears as an expansile lucent lesion that is sharply demarcated from adjacent normal bone. It may contain thin septa (scalloping of underlying cortex) that produce a multiloculated appearance. A simple bone cyst tends to have an oval configuration, with its long axis parallel to that of the host bone.

W86

AJR:193, August 2009

w79

08.18.09

Eisenberg

Fig. 16Simple bone cyst (fallen fragment sign). After pathologic fracture, cortical bone fragment (arrow) lies free in subtrochanteric bone cyst. (Reprinted with permission from Reynolds J. Fallen fragment sign in diagnosis of unicameral bone cysts. Radiology 1969; 92:949953)

Hyperparathyroidism

Patients with hyperparathyroidism (Fig. 17) (especially the primary type) may develop socalled brown tumors, which are true cysts representing intraosseous hemorrhage. In most cases, there is other radiographic evidence of hyperparathyroidism. A large lesion may simulate malignancy or lead to pathologic fractures and bizarre deformities. Brown tumors appear radiographically as single or multiple focal lytic areas that are generally well demarcated and often cause expansion of bone. They most commonly involve the mandible, pelvis, ribs, and femur.

A

Fig. 17Hyperparathyroidism (brown tumors). Multiple lytic lesions in pelvis (A) and about knee (B).

AJR:193, August 2009

W87

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Infection

Focal areas of lytic destruction, often with sclerosis and periosteal reaction, may occur with various infectious processes (Fig. 18). In fungal disease (coccidioidomycosis; blastomycosis), the lesions are often multiple. A large central radiolucent area associated with endosteal scalloping and expansion, which may have cortical breakthrough and a soft-tissue mass, is one appearance of echinococcal cyst involving the skeleton. This condition is usually monostotic and predominantly involves the pelvis, spine, and long bones. A rare manifestation of disseminated tuberculosis in children is single or multiple small oval lucencies with well-defined margins lying in the long axis of a bone, primarily the skull, shoulder, pelvic girdle, and axial skeleton.

Fig. 18Infection (coccidioidomycosis). Typical well-marginated, punched-out lytic defect in head of third metacarpal (arrows). (Reprinted with permission from McGahan JP, Graves DS, Palmer PE, Stadalnik RC, Dublin AB. Classic and contemporary imaging of coccidiodomycosis. AJR 1981; 136:393404)

W88

AJR:193, August 2009

w79

08.18.09

Eisenberg

Chondroblastoma

Chondroblastoma (Fig. 19) is the classic epiphyseal lesion, which occurs in children and young adults before enchondral bone growth ceases. It also may involve the greater trochanter of the femur and the greater tuberosity of the humerus. This rare, benign cartilaginous tumor typically appears radiographically as an eccentric, round or oval epiphyseal lucency that often has a thin sclerotic rim and may contain flocculent calcification.

Fig. 19Chondroblastoma. Osteolytic lesion containing calcification (arrows) in epiphysis. Note open epiphyseal line. (Reprinted with permission from Edeiken J. Roentgen diagnosis of diseases of bone. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1981)

Chrondromyxoid Fibroma

Chrondromyxoid fibroma (Fig. 20) is an uncommon benign bone tumor originating from cartilage-forming connective tissue and predominantly occurring in young adults. Calcification is infrequent (unlike chondroblastoma and other cartilaginous bone lesions). Approximately 50% of chondromyxoid fibromas involve the tibia, with the remainder affecting the pelvis and other bones of the extremities). A chondromyxoid fibroma typically appears radiographically as an eccentric, round or oval lucency arising in the metaphysis of a long bone. The overlying cortex is usually bulging and thinned, and the inner border is generally thick and sclerotic, often with scalloped margins.

Fig. 20Chondromyxoid fibroma. Ovoid, eccentric metaphyseal lucency with thinning of overlying cortex and sclerotic inner margin.

AJR:193, August 2009

W89

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Additional Lesions

Among other lesions that may infrequently appear as bubbly lesions are the following (in alphabetical order): Adamantinoma Angiomatous lesion Central chondrosarcoma Epidermoid inclusion cyst Fibrous cortical defect Glomus tumor Hemangioma Hemophilic pseudotumor Intraosseous ganglion Lipoma Lymphoma Ossifying fibroma Pigmented villonodular synovitis Sarcoidosis

Fig. 21Adamantinoma. Multiloculated eccentric, expansile, well-circumscribed lesion in characteristic location in midportion of tibia.

Fig. 22Angiomatous lesion (hemangioendothelioma). Expansile lucency containing delicate bony trabeculation.

W90

AJR:193, August 2009

w79

08.18.09

Eisenberg

Adamantinoma

Adamantinoma (Fig. 21) is a rare tumor that primarily affects adolescents and young adults and classically involves the tibia. It often recurs and may metastasize. Radiographically, an adamantinoma typically appears as a large loculated, expansile lucent mass in the midportion of the tibia.

Angiomatous Lesion

An angiomatous lesion (Fig. 22) is a rare congenital malformation consisting of endotheliumlined structures that may be lymphatic channels (lymphangiomatosis) or blood vascular channels (hemangiomatosis). Usually there is widespread involvement of multiple long bones, flat bones, and the skull. It typically appears as multiple (less commonly single) lucent metaphyseal lesions that often have a sclerotic margin and are sometimes associated with a soft-tissue mass.

Central Chondrosarcoma

Central chondrosarcoma (Fig. 23), a malignant tumor of cartilaginous origin, may originate de novo or in a preexisting cartilaginous lesion (osteochondroma, enchondroma). The tumor is about half as common as osteogenic sarcoma, develops at a later age (half the patients are more than 40 years old), grows more slowly, and metastasizes later. Central chondrosarcoma may also appear as an aggressive, poorly defined osteolytic lesion that blends imperceptibly with normal bone and can expand to replace the entire medullary cavity (this may simply be a later phase of the first, benign-appearing type). Radiographically, central chondrosarcoma appears as a localized lucent area of osteolytic destruction in the metaphyseal end of a bone. When the rate of tumor growth exceeds that of bone repair, the margins of the lesion become irregular and ill defined and the tumor extends to cause cortical destruction and invasion of soft tissues. The cartilaginous tissue in a chondrosarcoma can be easily recognized by the amorphous punctate, flocculent, or snowflake calcifications that are seen in approximately two thirds of central tumors.

Fig. 23Central chondrosarcoma. Irregular and illdefined lytic lesion of lower ilium.

Fig. 24Fibrous cortical defect. Multilocular, eccentric lucency in distal tibia. Note thin, scalloped rim of sclerosis.

AJR:193, August 2009

W91

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Epidermoid Inclusion Cyst

An epidermoid inclusion cyst appears radiographically as a well-circumscribed lucency in a terminal phalanx. It may cause thinning, expansion, or even loss of the cortical margin. Unlike an enchondroma, there is usually a history of penetrating trauma and no stippled calcification.

Fibrous Cortical Defect

Fibrous cortical defect (Fig. 24) is not a true neoplasm, but rather a benign and asymptomatic small focus of cellular fibrous tissue causing an osteolytic lesion in the metaphyseal cortex of a long bone (most frequently the distal femur). One or more fibrous cortical defects develop in up to 40% of all healthy children. Most regress spontaneously and disappear by the time of epiphyseal closure. A persistent and growing lesion is termed nonossifying fibroma. A fibrous cortical defect is generally a small, often multilocular, eccentric lucency that causes cortical thinning and expansion and is sharply demarcated by a thin, scalloped rim of sclerosis. Initially round, the defect soon becomes oval with its long axis parallel to that of the host bone.

Glomus Tumor

A glomus tumor appears radiographically as a central well-circumscribed lucency that primarily involves the distal aspect of the terminal phalanx of a finger. A glomus tumor may mimic an enchondroma, but is generally painful. A subungual glomus tumor may cause pressure erosion at that site.

Hemangioma

A hemangioma (Fig. 25) can rarely appear as a lucent area with delicate bony trabeculation, most commonly near the end of a tubular or flat bone. Much more commonly, a skeletal hemangioma produces multiple coarse linear striations running vertically in a demineralized vertebral body or a sunburst pattern of osseous spicules radiating from a central lucency in the skull.

Fig. 25Hemangioma (vertebral body). Multiple coarse, linear striations run vertically in demineralized vertebral body.

Fig. 26Lipoma. Expansile lucency with thinned cortex in characteristic location in calcaneus. (Courtesy of Jim Wu, Boston, MA)

W92

AJR:193, August 2009

w79

08.18.09

Eisenberg

Hemophilic Pseudotumor

In patients with hemophilia, an extensive local area of intraosseous hemorrhage may involve the femur, pelvis, tibia, and small bones of the hands. It appears radiographically as a central or eccentric lucent lesion, often with a large adjacent soft-tissue hemorrhage. There may be cortical erosion suggesting a sarcoma.

Intraosseous Ganglion

An intraosseous ganglion appears radiographically as a well-defined lucency with a sclerotic margin adjacent to the articular surface. It most commonly involves the proximal tibia (near the attachment of the cruciate ligaments), the head and neck of the femur, and the medial malleolus.

Lipoma

Lipoma (Fig. 26) is a rare bone tumor that arises in the calcaneus, skull, ribs, or extremities. It appears radiographically as an expansile lucency with a thinned cortex. The lesion may break through the cortex and have an adjacent soft-tissue component.

Lymphoma

Lymphoma (Fig. 27) may produce single or multiple lytic defects, often with endosteal scalloping of the cortex. A mottled pattern of destruction and sclerosis may simulate hematogenous metastases.

Fig. 27Lymphoma. Focal lytic defect with endosteal scalloping of cortex.

AJR:193, August 2009

W93

w79

08.18.09

Bubbly Lesions of Bone

Ossifying Fibroma

Ossifying fibroma is a rare tumor that may be associated with reactive bone sclerosis or calcification of the tumor matrix. It typically presents radiographically as a smooth, round, or expansile mass involving the skull, face, or mandible.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Protrusion of proliferative synovium in this condition infrequently produces a synovial cystic mass that can mimic a giant cell tumor and present as a lucent lesion extending to the articular surface.

Sarcoidosis

Perivascular granulomatous infiltration of sarcoidosis (Fig. 28) in the haversian canals of bone may destroy the fine trabeculae and produce a mottled or lacelike coarsely trabeculated pattern. Radiographically, this appears as single or multiple sharply circumscribed, punchedout areas of lucency, primarily involving the small bones of the hands and feet. There may be cortical thinning, expansion, or destruction.

Fig. 28Sarcoidosis. Multiple osteolytic lesions throughout phalanges with typical punched-out appearance. Apparent air density in soft tissues is photographic artifact.

W94

AJR:193, August 2009

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hip Neck Fracture, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDe la EverandHip Neck Fracture, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iseasesof ONE: Section I Pseudo-DiseasesDocument16 paginiIseasesof ONE: Section I Pseudo-Diseasesseunnuga93Încă nu există evaluări

- Giant Cell TumorDocument22 paginiGiant Cell TumorMaxmillian Alexander KawilarangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Osteonecrosis of The Femoral Head: Evaluation and TreatmentDocument10 paginiOsteonecrosis of The Femoral Head: Evaluation and TreatmentHector Ulises Quintanilla SotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ganglion of The Hand and WristDocument13 paginiGanglion of The Hand and WristtantraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of Patellofemoral Chondral InjuriesDocument24 paginiManagement of Patellofemoral Chondral InjuriesBenalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unhappy TriadDocument2 paginiUnhappy Triadbuffboy6Încă nu există evaluări

- History of Spine InstrumentationDocument35 paginiHistory of Spine InstrumentationSyarifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classification AO PediatricDocument36 paginiClassification AO PediatricdvcmartinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patellar InstabilityDocument16 paginiPatellar InstabilitydrjorgewtorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fracture ComplicationDocument29 paginiFracture Complicationlgtoalejandro100% (1)

- Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis PDFDocument5 paginiSpondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis PDFchandran2679Încă nu există evaluări

- Giant Cell TumorDocument35 paginiGiant Cell TumorHestikrnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ficat and Arlet Staging of Avascular Necrosis of Femoral HeadDocument6 paginiFicat and Arlet Staging of Avascular Necrosis of Femoral HeadFernando Sugiarto0% (1)

- AO Classification of FracturesDocument62 paginiAO Classification of FracturesEka Sutiono100% (1)

- Acute Distal Radioulnar Joint InstabilityDocument13 paginiAcute Distal Radioulnar Joint Instabilityyerson fernando tarazona tolozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fracture of The Femoral NeckDocument21 paginiFracture of The Femoral NeckSalsabila Al-BasheerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legg Calvé Perthes DiseaseDocument11 paginiLegg Calvé Perthes DiseaseronnyÎncă nu există evaluări

- DislocationDocument46 paginiDislocationShaa ShawalishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acetabular Fracture PostgraduateDocument47 paginiAcetabular Fracture Postgraduatekhalidelsir5100% (1)

- 1.26 (Surgery) Orthopedic Pathology - OncologyDocument7 pagini1.26 (Surgery) Orthopedic Pathology - OncologyLeo Mari Go LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orthopaedic Surgery Study Guide FOR Medical Students, R1S and R2SDocument17 paginiOrthopaedic Surgery Study Guide FOR Medical Students, R1S and R2SlanghalilafaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MPFL ReconstructionDocument16 paginiMPFL ReconstructiondrjorgewtorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articular Fractures PrinciplesDocument9 paginiArticular Fractures PrinciplesSylviany El NovitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Column AnkleDocument8 pagini3 Column AnkleJosé Eduardo Fernandez RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pelvic FractureDocument31 paginiPelvic Fracturepoe3Încă nu există evaluări

- Why Every Spine Fusion Can Be A Deformity?Document88 paginiWhy Every Spine Fusion Can Be A Deformity?PaulMcAfeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Skeletal Radiology LengkapDocument89 paginiSkeletal Radiology LengkapRivani KurniawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avascular Necrosis of The Fibular SesamoidDocument7 paginiAvascular Necrosis of The Fibular SesamoidAlex Yvan Escobedo HinostrozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arm:Leg Fracture PDFDocument11 paginiArm:Leg Fracture PDFHannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Club Foot PDFDocument54 paginiClub Foot PDFBelle Sakunrat SarikitÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHAPTER 14 - Treatment of Bone Def - 2008 - Surgical Techniques of The ShoulderDocument11 paginiCHAPTER 14 - Treatment of Bone Def - 2008 - Surgical Techniques of The ShoulderJaime Vázquez ZárateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modified French OsteotomyDocument5 paginiModified French OsteotomyKaustubh KeskarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Malunions of The Distal RadiusDocument14 paginiMalunions of The Distal RadiusSivaprasath JaganathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benign Bone TumorDocument42 paginiBenign Bone Tumorsaqrukuraish2187Încă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus Ms OrthoDocument8 paginiSyllabus Ms OrthoMuthu KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bone and Soft Tissue SarcomaDocument67 paginiBone and Soft Tissue SarcomaSalmanArifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giant Cell ReparativeDocument3 paginiGiant Cell ReparativeMedrechEditorialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orthopedic: Dislocations of The Hip JointDocument16 paginiOrthopedic: Dislocations of The Hip JointAnmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Missed Monteggia FXDocument16 paginiMissed Monteggia FXEric RothÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCL's Avulsion FractureDocument22 paginiPCL's Avulsion FractureNey da OnneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fracture of The Talus and Calcaneus NickDocument43 paginiFracture of The Talus and Calcaneus NickTan Zhi HongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acetabular Fractures: Dr. Roshan DDocument65 paginiAcetabular Fractures: Dr. Roshan DKaizar EnnisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bone Grafts and SubstitutesDocument85 paginiBone Grafts and Substitutessandeepvella100% (1)

- Bone AgeDocument65 paginiBone AgeueumanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arthroscopic Ankle ArthrodesisDocument37 paginiArthroscopic Ankle ArthrodesisJan VelosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cubitus VarusDocument9 paginiCubitus VarusMisoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approach To FractureDocument17 paginiApproach To FractureRebecca WongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blount's Disease (Textbook)Document17 paginiBlount's Disease (Textbook)Fadzhil AmranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neoplasm On Bone and Soft Tissue MikoDocument151 paginiNeoplasm On Bone and Soft Tissue Mikoindra muhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trauma UrethraDocument19 paginiTrauma UrethraAtika SugiartoÎncă nu există evaluări

- TBWDocument45 paginiTBWveedee cikalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Percutaneous Imaging-Guided Spinal Facet Joint InjectionsDocument6 paginiPercutaneous Imaging-Guided Spinal Facet Joint InjectionsAlvaro Perez HenriquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dasar-Dasar Radiologi Musculoskeletal PDFDocument101 paginiDasar-Dasar Radiologi Musculoskeletal PDFIndra MahaputraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acetabular FractureDocument136 paginiAcetabular FracturePicha PichiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trochanteric #Document20 paginiTrochanteric #Prakash AyyaduraiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fracture Classifications in OrthopaedicsDocument33 paginiFracture Classifications in Orthopaedicsmario100% (2)

- Anterior Knee Pain Syndrome ReferatDocument28 paginiAnterior Knee Pain Syndrome ReferatnurulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal Orthobullets MBDDocument8 paginiSoal Orthobullets MBDAdi RiyadliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bone Tumors: Prepared by DR Pgr.2 Ortho Unit 3 BMCHDocument47 paginiBone Tumors: Prepared by DR Pgr.2 Ortho Unit 3 BMCHMohamed Al-zichrawyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disorders of Diverticulation and Cleavage, Sulcation andDocument48 paginiDisorders of Diverticulation and Cleavage, Sulcation andagoyal_9Încă nu există evaluări

- Acute Abdominal DiseaseDocument11 paginiAcute Abdominal Diseaseagoyal_9Încă nu există evaluări

- Differential Diagnosis MnemonicsDocument283 paginiDifferential Diagnosis Mnemonicstyagee100% (16)

- CNS Infections 2003Document58 paginiCNS Infections 2003agoyal_9Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Thesis - Aris PotliopoulosDocument94 paginiFinal Thesis - Aris PotliopoulosCristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10th ORLIAC Scientific Program As of 26 Jan 2018Document6 pagini10th ORLIAC Scientific Program As of 26 Jan 2018AyuAnatrieraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Involved in Floating Paper Clip Science Experiment GuidelinesDocument4 paginiScience Involved in Floating Paper Clip Science Experiment GuidelinesSHIELA RUBIOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zincanode 304 pc142Document3 paginiZincanode 304 pc142kushar_geoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brief Summary of Catalytic ConverterDocument23 paginiBrief Summary of Catalytic ConverterjoelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intumescent Paint For Steel NZ - Coating - Co.nzDocument8 paginiIntumescent Paint For Steel NZ - Coating - Co.nzPeter ThomsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thermoplastic Tubing: Catalogue 5210/UKDocument15 paginiThermoplastic Tubing: Catalogue 5210/UKGeo BuzatuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poems Prescribed For 2012-2014 English B CSEC ExamsDocument24 paginiPoems Prescribed For 2012-2014 English B CSEC ExamsJorge Martinez Sr.100% (2)

- MiscanthusDocument27 paginiMiscanthusJacob GuerraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 5 AGVDocument76 paginiChapter 5 AGVQuỳnh NguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unofficial Aterlife GuideDocument33 paginiThe Unofficial Aterlife GuideIsrael Teixeira de AndradeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approved Project 25 StandardsDocument5 paginiApproved Project 25 StandardsepidavriosÎncă nu există evaluări

- QuantAssay Software Manual 11-Mar-2019Document51 paginiQuantAssay Software Manual 11-Mar-2019LykasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dialog Bahasa InggirsDocument2 paginiDialog Bahasa InggirsKeRtha NeghaRaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Microbiology Part 3Document74 paginiMicrobiology Part 3Authentic IdiotÎncă nu există evaluări

- S590 Machine SpecsDocument6 paginiS590 Machine SpecsdilanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eliminating Oscillation Between Parallel MnosfetsDocument6 paginiEliminating Oscillation Between Parallel MnosfetsCiprian BirisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meet The Profesor 2021Document398 paginiMeet The Profesor 2021Raúl AssadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hot Topic 02 Good Light Magazine 56smDocument24 paginiHot Topic 02 Good Light Magazine 56smForos IscÎncă nu există evaluări

- Future AncestorsDocument44 paginiFuture AncestorsAlex100% (1)

- Present Simple TaskDocument3 paginiPresent Simple TaskMaria AlejandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ii 2015 1Document266 paginiIi 2015 1tuni santeÎncă nu există evaluări

- By This Axe I Rule!Document15 paginiBy This Axe I Rule!storm0% (1)

- 1ST SUMMATIVE TEST FOR G10finalDocument2 pagini1ST SUMMATIVE TEST FOR G10finalcherish austriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aesculap Saw GD307 - Service ManualDocument16 paginiAesculap Saw GD307 - Service ManualFredi PançiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trends in FoodDocument3 paginiTrends in FoodAliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Affecting Physical FitnessDocument7 paginiFactors Affecting Physical FitnessMary Joy Escanillas Gallardo100% (2)

- HY-TB3DV-M 3axis Driver PDFDocument10 paginiHY-TB3DV-M 3axis Driver PDFjoelgcrÎncă nu există evaluări

- YogaDocument116 paginiYogawefWE100% (2)

- Iron Ore ProcessDocument52 paginiIron Ore Processjafary448067% (3)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDe la EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe la EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (28)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDe la EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDe la EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe la EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (81)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDe la EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (404)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (42)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDe la EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (6)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDDe la EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDe la EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.De la EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (110)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDe la EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDe la EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (170)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDe la EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (3)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerDe la EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (392)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningDe la EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (3)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosDe la Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (207)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryDe la EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (44)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDe la EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (328)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlDe la EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (58)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsDe la EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (6)