Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Characterize

Încărcat de

Arie Arma ArsyadDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Characterize

Încărcat de

Arie Arma ArsyadDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

This article was downloaded by: [aqil rusli] On: 18 December 2011, At: 18:26 Publisher: Routledge Informa

Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

International Journal of Science Education

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsed20

Essential Criteria to Characterize Constructivist Teaching: Derived from a review of the literature and applied to five constructivistteaching method articles

Sandhya N. Baviskar , R. Todd Hartle & Tiffany Whitney

a a a a

Idaho State University, USA

Available online: 11 Mar 2009

To cite this article: Sandhya N. Baviskar , R. Todd Hartle & Tiffany Whitney (2009): Essential Criteria to Characterize Constructivist Teaching: Derived from a review of the literature and applied to five constructivistteaching method articles, International Journal of Science Education, 31:4, 541-550 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500690701731121

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

International Journal of Science Education Vol. 31, No. 4, 1 March 2009, pp. 541550

RESEARCH REPORT

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

Essential Criteria to Characterize Constructivist Teaching: Derived from a review of the literature and applied to five constructivist-teaching method articles

Sandhya N. Baviskar*1, R. Todd Hartle and Tiffany Whitney

Idaho State University, USA

bavisand@isu.edu Ms. 0000002007 Journal of 00 SandhyaBaviskar Taylor and (print)/1464-5289 (online) 2007 & Report Ltd Science Education Research Francis 0950-0693 Francis International 10.1080/09500690701731121 TSED_A_273047.sgm

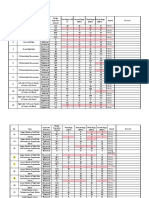

Constructivism is an important theory of learning that is used to guide the development of new teaching methods, particularly in science education. However, because it is a theory of learning and not of teaching, constructivism is often either misused or misunderstood. Here we describe the four essential features of constructivism: eliciting prior knowledge, creating cognitive dissonance, application of new knowledge with feedback, and reflection on learning. We then use the criteria we developed to evaluate five representative published articles that claim to describe and test constructivist teaching methods. Of these five articles, we demonstrate that three do not adhere to the constructivist criteria, whereas two provide strong examples of how constructivism can be employed as a teaching method. We suggest that application of the four essential criteria will be a useful tool for all professional educators who plan to implement or evaluate constructivist teaching methods.

Introduction Constructivism is an important and driving theory of learning in modern education. However, the difficulty in defining and implementing constructivism as a practical methodology has created misconceptions because lesson plans that claim to be constructivist do not have all the elements that are required by constructivism and also often include elements that deviate from constructivist theory. The goal of this

*Corresponding author. Department of Biological Sciences, Gale Life Science Center, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID 83209-8007, USA. Email: bavisand@isu.edu ISSN 0950-0693 (print)/ISSN 1464-5289 (online)/09/04054110 2009 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/09500690701731121

542 S.N. Baviskar et al. article is to generate a list of constructivism-defining criteria, and to demonstrate their use by evaluating five representative papers whose stated goals were to describe and test a constructivist course design in secondary or post-secondary science courses. The descriptive and theoretical literature on constructivism is fragmented (Crowther, 1999; Jenkins, 2000). Some articles explore the basic tenets of constructivism (Richardson, 2003; Windschitl, 2002; Yager, 1991), but the descriptions are often theoretical without illustrating how these tenets can be put into practice. Some authors present specific constructivist teaching methodologies that require certain elements such as group work (Lord, 1994). Although group activity may be necessary for the described teaching method, it may not be essential for the method to be considered constructivist, but often this element is mistakenly considered one of the essential elements of constructivism. Other articles provide rich descriptions and examples of constructivist practice without stressing the elements that make them constructivist (Vermette et al., 2001). These descriptions could be useful to practitioners looking for teaching tips, but do not reveal the essence of constructivism. There is also confusion between personal constructivism, the theory of individual learning, and social constructivism, a theory concerning the origins of knowledge in a culture. Social constructivism states that cultures or groups construct their knowledge bases through the discourse and interactions among their members rather than through the discoveries of individuals or the dictation of authorities (Marin, Benarroch, & Jimenez-Gomez, 2000; Rodriguez & Berryman, 2002). Many educators assume that if their students are working in groups, the lesson must be constructivist because social constructivism states that knowledge is negotiated through interactions. However, social constructivism does not say anything about how an individual acquires the knowledge for passing a college biology course. The personal constructivist theory that is the topic of this paper (also called psychological or cognitive constructivism) does not say that learning occurs only in groups or even that learning necessarily occurs best in groups. Consequently, group work may be a constructivist educational tool, or it may not be, depending entirely on the implementation. Constructivism is a theory of learning and not a theory of curriculum design (Airasian & Walsh, 1997; Richardson, 2003). Therefore, when a lesson is said to be constructivist, it does not necessarily follow a specific formula. Instead a constructivist lesson is one that is designed and implemented in a way that creates the greatest opportunities for students to learn, regardless of the techniques used. Implementation of the theory is the crux of constructivism. Large lecture halls are often held up as the antithesis of constructivism. However, if an instructor needs to transmit a large amount of information to a large group of expert learners, and the lesson is properly implemented, a lecture is probably the most efficient constructivist tool possible (Richardson, 2003). In this paper, we have distilled the required characteristics of constructivism and formalized them into four criteria required to designate a methodology as constructivist.

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

Criteria to Characterize Constructivist Teaching Definitions: Four constructivist criteria

543

The theory of constructivism states that the knowledge possessed by an individual is connected in a comprehensive construct of facts, concepts, experiences, emotions, values, and their relationships with each other. If the construct is insufficient or incorrect when compared with the information the individual is gathering from the environment, the individual will experience a form of cognitive dissonance that will act as a motivation (Lorsbach & Tobin, 1993). The individual will be motivated to reject the new information or incorporate it into his or her construct (Berger, 1978; Novak & Gowin, 1986; Sewell, 2002). In order to make any changes to the knowledge construct permanent, the learner must be able to apply the changed construct to novel situations, receive feedback about the validity of the construct from other sources, and establish further connections to other elements in the construct. The fact that constructivism is learner oriented is essential to any constructivist lesson plan or curriculum (Richardson 2003; Vermette et al., 2001; Yager, 1991). It is not considered one of the four criteria because it is a basic and pervasive concept. The constructivist teachers role is to create a context where the learner is motivated to learn, which includes providing content and resources, posing relevant problems and questions at appropriate times (Wheatley, 1991, p. 14; Windschitl, 2002, p. 137), and linking these resources and questions to the students prior knowledge. There are four critical elements that must be addressed in the activities, structure, content, or context of a lesson for it to be considered constructivist. The first criterion is eliciting prior knowledge. Constructivism presupposes that all knowledge is acquired in relation to the prior knowledge of the learner (Naylor & Keogh, 1999; Sewell, 2002; Vermette et al., 2001; Windschitl, 2002; Yager, 1991). If the educator does not have a mechanism for eliciting the prior knowledge of the students, the new knowledge cannot be gainfully presented in a way that can be incorporated into the learners construct. Likewise, if the learners attention is not drawn to their prior knowledge, the learner will either ignore or incorrectly incorporate the new knowledge. Prior knowledge can be elicited in different ways: formal pre-tests, asking informal questions, formal interviews with students, or setting up activities such as conceptmapping that require basic knowledge to be applied. The key element in the criterion of eliciting prior knowledge is to make sure that the activity assesses the learners prior knowledge and relates it to the new knowledge. For example, having successfully completed a unit on the process of meiosis does not imply that the students understand genetic segregation. Also, merely checking the completion of an activity by students (e.g., having done assigned readings) will not give sufficient information to the instructor about their prior knowledge. On the other hand, an activity like having the students create a concept map of their prior knowledge on a topic is an excellent method of eliciting prior knowledge. The students are required to present everything they know about the topic in the form of a network of concepts and the relations among them. The combination of both eliciting and organizing the information in the form of a map that resembles the students own cognitive construct allows the

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

544 S.N. Baviskar et al. student and the teacher to assess any misconceptions and target the implementation of the lesson plan accordingly. The second criterion is creating cognitive dissonance. The learner must be made aware of a difference between his/her prior knowledge and the new knowledge (Inch, 2002; Sewell, 2002). Wheatley (1991, p. 15) states that in preparation for a class, a teacher selects tasks which have a high probability of being problematical for studentstasks which may cause students to find a problem. If students are presented with new knowledge in a way that assumes they should acquire this knowledge independent of their prior knowledge, the lesson is deterministic and cannot be considered constructivist. The third criterion is application of the knowledge with feedback (Vermette et al., 2001; Windschitl, 2002; Yager, 1991). Misinterpretation or rejection of new knowledge is likely if the learner does not interpret and modify prior knowledge in the context of new knowledge. Application of the new construct could be in the form of quizzes, presentations, group discussions, or other activities where the students compare their individual constructs with their cohorts or with novel situations. In addition to checking the validity of their constructs, application allows the student to further define the interconnectedness of the new knowledge to a greater variety of contexts, which will integrate the new knowledge permanently. The fourth criterion is reflection on learning. Once the student has acquired the new knowledge and verified it, the student needs to be made aware of the learning that has taken place (Windschitl, 2002; Yager, 1991). Constructivist lessons will provide the student with an opportunity to express what he or she has learned. Reflection could be attained using traditional assessment techniques such as presentations, papers, or examinations, if the questions on the examinations fostered reflection on the learning process (Saunders, 1992). Activities that are more meta-cognitive in nature might include a reflexive paper, a return to the dissonance creating activity, or having the student explain a concept to a fellow student (Lord, 1994). Although the reflection criterion does not necessarily have to be a formal part of the lesson plan, its presence makes the lesson considerably more constructivist. Implementation: Review of published articles using constructivist criteria Although, there are specific teaching methodologies that are strongly constructivist, such as inquiry-based teaching methods, it is not necessary to use one of these methods to be constructivist. Likewise, simply following a methodology in a cookbook fashion will not guarantee constructivism. In this section, five articles whose authors specifically claim to have implemented constructivist-teaching methods are evaluated according to the four criteria defined above. Article 1: Using computers to create constructivist learning environments: Impact on pedagogy and achievement Huffman, Goldberg, and Michlin (2003) asked: To what extent can computers be used to help teachers create a constructivist learning environment in the science

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

Criteria to Characterize Constructivist Teaching

545

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

classroom? They used a project called Constructing Physics Understanding (CPU). CPU is a curriculum designed to meet the US National Science Education Standards (National Research Council [NRC], 1996). It has computer-based modular activities, software, and curricula to help teachers create a learning environment. The study examined three groups of teachers: (1) teachers who fully adopted the new pedagogy and computer-based materials (termed Lead CPU teachers); (2) teachers who were newly trained and modified some of the CPU pedagogy (Beginning CPU teachers); and (3) the comparison teachers who used traditional instructional methods. In all, 13 teachers were examined to determine the extent to which computers can alter pedagogy and student achievement. The authors describe three vignettes as representative of classroom teaching of each of the three groups. The lead CPU teachers class did not meet any of our criteria for constructivist teaching. The authors claimed that because the lead CPU teacher knew the students had performed a specific experiment prior to the lesson, the teachers were aware of the students prior knowledge. We did not find any evidence of dissonance being created by the teacher in students minds. Neither was there any specific application of new knowledge nor review of the learning process. The students and teachers seemed to be following the procedures and activities step-by-step as described in the CPU curriculum project. Huffman et al. (2003) state that their data suggest computers help teachers create more constructivist learning environments. We think the comparison done in the study is not appropriate to address the research question. There were several confounding factors including the experience levels of the teachers and differential access to properly working computers by different groups of teachers. It is not possible to determine which factors were responsible for students higher achievement. Without further experimental probing, it could even be argued that the experienced teachers would create a more constructivist-learning environment without computers than less experienced teachers could with computers. Article 2: Constructivism in mass higher education: A case study Stephen J. Bostock (1998) describes the design, implementation, and evaluation of a web-based course and claims that it is based on constructivist educational principles. Lectures were conducted by the author once per week for one hour and laboratory sessions were presented by two demonstrators for two hours per week. Instructional methods also included a computer-assisted learning package and other resourcebased learning including videos and web pages. Students were required to demonstrate practical skills in the laboratory and to generate summaries and concept maps based on the tasks. The author summarizes five principles that make an environment rich for what he calls active/constructivist learning: authentic assessment, student responsibility and initiative, generative learning strategies, authentic learning contexts, and cooperative support. According to our criteria, authentic assessment, authentic learning context, and cooperative support are not essential features of constructivist teaching. The

546 S.N. Baviskar et al. type of assessment can only affect constructivist learning if it offers opportunities for application of new knowledge that was not demonstrated by the author. Authentic learning contexts may or may not create dissonance or provide opportunity for application of knowledge depending on their application. Finally, as stated earlier, group activities are not necessarily constructivist (Richardson, 2003). The article fails in meeting most of our criteria of constructivist paedagogy. The teacher neither elicits prior knowledge of the students nor creates any dissonance in their knowledge structure with the result that the students lost interest in the course as confirmed by the author (Bostock, 1998, p. 230). The students were allowed to choose their research topics and create their own web pages in consultation with the teacher, which is an example of application of knowledge with feedback (the only constructivist technique we found). The author considers cooperative learning an important principle of constructivist teaching but admits that the cooperative group work failed. He reasons that the attendance was thin, and with very little teacher student and studentstudent interactions the students found it more convenient to work alone than in groups. Finally, students were required to reflect on their own learning by maintaining a diary, but only 13% participated. The author states that the content of the course was not decided by the instructor alone but was negotiated with the students, which, according to the author, is a student-centred approach, and hence constructivist. But negotiation on course content with the students has no relevance to constructivism. In reading this article, one gets the impression that the author had no control over the implementation of the course. He admits his failures on various fronts, but draws consolation by saying it is cheering to think that a partial implementation of constructivist principles may actually be optimal for the majority of students (Bostock, 1998, p. 236). Article 3: Constructing knowledge in the lecture hall Daniel Klionsky (1998) modified his teaching methods in an attempt to adopt a constructivist teaching style. His first goal was to alter the study habits of students by eliminating reading assignments from the textbook and instead supplying the students with his lecture notes prior to class. Students were then quizzed on the reading material at the beginning of each class session. He wrote that this method would limit the amount of reading for which his students were responsible, while encouraging them to come to class prepared. His second goal was to create a learning environment that fostered constructivism. Group problem-solving activities were implemented in order to promote student interaction and a hands-on problem-solving experience. The students were then quizzed on the material they learned from the group activity. Although, the group activities appear to have been a useful pedagogical tool, as mentioned previously, group work alone does not define a lesson as constructivist. The modifications made in teaching methods appear to have improved students performance as well as the students approval of the course and the instructor. However, the new teaching methods did not meet the criteria for constructivism. The

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

Criteria to Characterize Constructivist Teaching

547

author did not use a comprehensive evaluation of the prior knowledge of the students, or give any evidence that cognitive dissonance occurred in the students. The quizzes may or may not have given the students an opportunity to apply their new knowledge and receive feedback, but they certainly were not a mechanism for reflection. Klionsky (1998) did evaluate the effectiveness of his methods and he does appear to have promoted an improvement in student performance. He used comparisons of current quiz and test scores with those of previous years and noted a general improvement. He also compared course evaluations from the two teaching methods and found that the students preferred his new method. The new teaching methods adopted by the author appear to have improved his students learning, but these new methods were not entirely based on constructivist principles. Article 4: A student-centered approach to teaching general biology that really works: Lords constructivist model put to a test Burrowes (2003) describes an experiment in which constructivism is tested in the classroom. She had three major goals: to help students achieve better grades on standard mid-term examinations, to develop higher level thinking skills, and to modify their attitude towards biology at this large, urban university. To meet these goals, two different biology classes with approximately 100 students each were taught using different methods. One class was taught using a traditional lecture and note-taking method, and the other was taught using what the author describes as experimental teaching based on the constructivist learning model. In the experimental group the author followed Yagers (1991) application of the constructivist learning model, Bybees (1993) 5E model, which is based on constructivism, and Lords (Lord, 1994, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2001) application of cooperative learning. She used a short lecture to engage her students and then had groups to formulate problems or exercises, which she considered the explore step. The students then explained what they had done. After students explained their problems and solutions that the author elaborated by addressing any questions or misconceptions that may have arisen, she then introduced the new material and referred it back to what was previously discussed. Burrowes (2003) followed the criteria for constructivist teaching. The combination of the explore and explain steps satisfied the first criterion of eliciting prior knowledge. The explain and elaboration steps created dissonance by explicitly comparing the students new and prior knowledge. The elaboration step satisfied the third criterion of application of knowledge with feedback. Finally, the fourth criterion was satisfied by the elaboration and evaluation steps in which the instructor assisted the students in realizing their recent learning. Overall, the author met the criteria for constructivist learning. In addition, the author showed that there was more learning in constructivist classroom than the traditional classroom. Although we question some of the techniques and statistical analyses used for comparing the performance of the students of the two classes, she did demonstrate greater learning in the constructivist classroom.

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

548 S.N. Baviskar et al. Article 5: Teaching of biological inheritance and evolution of living beings in secondary school Banet and Ayuso (2003) designed, implemented, and tested a constructivist secondary school biology unit on inheritance and evolution. The unit had four groupings of content goals. They elicited common misconceptions of the student population through a series of surveys, assessments, and pre-tests of the general student population as well as the students involved in their study. For each group of content goals, the authors identified a schema from the pre-tests as the correct conceptualization, as well as one to three schema based on common misconceptions. In the classroom, the authors used problem-solving lesson plans designed to explore the students misconceptions. Finally, the students were evaluated both in a post-test and a retention test (three months after the end of the lesson) using similar schema-based methods to the pre-tests. Banet and Ayuso (2003) used constructivism in a way that met all four criteria. Their efforts at eliciting prior knowledge for the general population of students as well as the individuals involved in their experimental unit were extensive. They explored the current level of content knowledge, the cognitive abilities, and the stages of cognitive development of the students. This comprehensive understanding of the students prior knowledge was then used at all stages of the educational process. It was made clear that prior knowledge is by far the most important element in the authors considerations. The authors used problem-solving lessons based on the students misconceptions in order to create dissonance in the minds of the students. The problems presented in the lessons were designed to demonstrate how the students current constructs were insufficient to solve the problems. These same problems also provided the opportunity to apply and test the new information. Banet and Ayuso (2003) also evaluated the success of their constructivist biology unit and found its performance satisfactory. They compared their students performance with their initial goals in the form of their schema. In all four content areas the results of the post-test and retention test were considerably better than those of the pre-test. In three of the four areas, the retention-test results were slightly less than those of the post-test. All in all, Banet and Ayuso (2003) presented a truly constructivist biology unit and demonstrated that it was successful. As the purpose of the authors was not to convince their readers that they used constructivist methods, they did not present all the information that would have been helpful to judge their unit in terms of our constructivist criteria as defined above. However, the details provided do show a thorough and appropriate understanding of constructivism as well as the practical issues involved in implementing the theory to actual science education. This paper is an excellent example of the proper use of constructivist theory in science education. Conclusion Our study of the literature on science education has revealed that constructivism and constructivist concepts are frequently mentioned, but essential elements of

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

Criteria to Characterize Constructivist Teaching

549

constructivism are often lacking. The descriptive literature on constructivism can be misunderstood by teachers and practitioners because the articles are esoteric and technical with little emphasis on their practical application, or they are descriptions of lessons that succeeded without emphasizing which elements made them constructivist. In addition, many constructivist lesson plans are transformed into un-constructivist lessons through misapplication and deterministic implementation. We think that greater rigour in the implementation of constructivist lesson plans and their proper presentation in the published literature are essential to the overall validity and respect for educational research, thereby easing the implementation of new teaching methodologies. Acknowledgements

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

The authors would like to thank Dr Rosemary Smith for valuable discussions, advice, and mentoring throughout the writing process. Note

1. Ms Baviskar is first author because the idea for a review paper exploring constructivism in science classrooms launched the original collaboration and because she performed most of the background and paper selection work. The ideas surrounding the four criteria of constructivism in the introduction were derived primarily from Mr Hartles background and training in educational theory and practice. In all other aspects, each of the three authors contributed equally to this work.

References

Airasian, P.W., & Walsh, M.E. (1997). Constructivist cautions. Phi Delta Kappan, 78(6), 449. Banet, E., & Ayuso, G.E. (2003). Teaching of biological inheritance and evolution of living beings in secondary school. International Journal of Science Education, 25(3), 373407. Berger, K.S. (1978). The developing person. New York: Worth Publishers. Bostock, S.J. (1998). Constructivism in mass higher education: A case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(3), 225240. Burrowes, P.A. (2003). A student-centered approach to teaching general biology that really works: Lords constructivist model put to a test. The American Biology Teacher, 65(7), 491501. Bybee, R. (1993). Instructional model for science education in developing biological literacy Colorado Springs, CO: Biological Sciences Curriculum Studies. Crowther, D.T. (1999). Cooperating with constructivism. Journal of College Science Teaching, 29(1), 1723. Huffman, D., Goldberg, F., & Michlin, M. (2003). Using computers to create constructivist learning environments: Impact on pedagogy and achievement. Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 22(2), 151168. Inch, S. (2002). The accidental constructivist a mathematicians discovery. College Teaching, 50(3), 111113. Jenkins, E.W. (2000). Constructivism in school science education: Powerful model or the most dangerous intellectual tendency? Science and Education, 9, 599610. Klionsky, D.J. (1998). Constructing knowledge in the lecture hall. Journal of College Science Teaching, 31(4), 246251.

550 S.N. Baviskar et al.

Lord, T.R. (1994). Using constructivism to enhance student learning in college biology. Journal of College Science Teaching, 23(6), 346348. Lord, T.R. (1997). Comparing traditional and constructivist teaching in college biology. Innovative Higher Education, 21(3), 197217. Lord, T.R. (1998). Cooperative learning that really works in biology teaching. Using constructivistbased activities to challenge student teams. The American Biology Teacher, 60(8), 580588. Lord, T.R. (1999). A comparison between traditional and constructivist teaching in environmental science. The Journal of Environmental Education, 30(3), 2228. Lord, T.R. (2001). 101 reasons for using cooperative learning in biology teaching. The American Biology Teacher, 63(1), 3038. Lorsbach, A., & Tobin, K. (1993). Constructivism as a referent for science teaching. NARST News, 34(3), 911. Marin, N., Benarroch, A., & Jimenez-Gomez, E. (2000). What is the relationship between social constructivism and Piagetian constructivism? An analysis of the characteristics of the ideas within both theories. International Journal of Science Education, 22(3), 225238. National Research Council (1996). National science education standards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Naylor, S., & Keogh, B. (1999). Constructivism in classroom: Theory into practice. Journal of Science Teachers Education, 10(2), 93106. Novak, J., & Gowin, D.B. (1986). Learning how to learn. New York: Cambridge University Press. Richardson, V. (2003). Constructivist pedagogy. Teachers College Record, 105(9), 16231640. Rodriguez, A.J., & Berryman, C. (2002). Using sociotransformative constructivism to teach for understanding in diverse classrooms: A beginning teachers journey. American Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 10171045. Saunders, W. (1992). The constructivist perspective: Implications and teaching strategies for science. School Science and Mathematics, 92(3), 136141. Sewell, A. (2002). Constructivism and student misconceptions. Australian Science Teachers Journal, 48(2), 2428. Vermette, P., Foote, C., Bird, C., Mesibov, D., Harris-Ewing, S., & Battaglia, C. (2001). Understanding constructivism(s): A primer for parents and school board members. Education, 122(1), 8793. Wheatley, G.H. (1991). Constructivist perspectives on science and mathematics learning. Science Education, 75(1), 921. Windschitl, M. (2002). Framing constructivism in practice as the negotiations of dilemmas: An analysis of the conceptual, pedagogical, cultural and political challenges facing teachers. Review of Educational Research, 72(2), 131175. Yager, R. (1991). The constructivist learning model, towards real reform in science education. The Science Teacher, 58(6), 5257.

Downloaded by [aqil rusli] at 18:26 18 December 2011

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Perspectives in Interdisciplinary and Integrative StudiesDe la EverandPerspectives in Interdisciplinary and Integrative StudiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Studies in Continuing Education: Please Scroll Down For ArticleDocument16 paginiStudies in Continuing Education: Please Scroll Down For Articlea4170131Încă nu există evaluări

- Organising A Culture of Argumentation in Elementary ScienceDocument23 paginiOrganising A Culture of Argumentation in Elementary ScienceZulpa zulpiandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constructivist PedagogyDocument7 paginiConstructivist Pedagogyapi-281038892Încă nu există evaluări

- Connected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeDe la EverandConnected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeTricia A. FerrettÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constructivism, Instructional Design, and Technology Implications For Transforming Distance LearningDocument12 paginiConstructivism, Instructional Design, and Technology Implications For Transforming Distance LearningMarcel MaulanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Confrey What Constructivism Implies For TeachingDocument33 paginiConfrey What Constructivism Implies For TeachingjillysillyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social and Radical ConstructivismDocument12 paginiSocial and Radical ConstructivismAmbrose Hans AggabaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trend Analysis Edci 520 1Document5 paginiTrend Analysis Edci 520 1api-340297029Încă nu există evaluări

- Constructivismo Vs CognitivismoDocument12 paginiConstructivismo Vs CognitivismoPablo David ZambranoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Principles of Curriculum and InstructionDe la EverandBasic Principles of Curriculum and InstructionEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (6)

- Action Research in Education: Jonida Lesha, Phd. CDocument8 paginiAction Research in Education: Jonida Lesha, Phd. CFille CaengletÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interactional Research Into Problem-Based LearningDe la EverandInteractional Research Into Problem-Based LearningSusan M. BridgesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Blended Learning: Shared Metacognition and Communities of InquiryDe la EverandPrinciples of Blended Learning: Shared Metacognition and Communities of InquiryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsDe la EverandThe Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Constructivist Theory and A Teaching and Learning Cycle in EnglishDocument12 paginiConstructivist Theory and A Teaching and Learning Cycle in EnglishTrang NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theoretical Framework 1Document16 paginiTheoretical Framework 1bonifacio gianga jrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating Formative Assessment and Feedback Into Scientific Theory Building Practices and InstructionDocument18 paginiIntegrating Formative Assessment and Feedback Into Scientific Theory Building Practices and InstructionMaria GuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knowledge and ConstructivismDocument2 paginiKnowledge and Constructivismapi-246360250Încă nu există evaluări

- Expansive Framing As Pragmatic Theory For Online and Hybrid Instructional DesignDocument32 paginiExpansive Framing As Pragmatic Theory For Online and Hybrid Instructional DesignsprnnzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constructivism The Roots of Military PedagogyDocument14 paginiConstructivism The Roots of Military PedagogyGlobal Research and Development Services100% (1)

- ArticleDocument12 paginiArticleDalia LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Theories PaperDocument3 paginiLearning Theories PaperryanosweilerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1877042815042974 Main PDFDocument6 pagini1 s2.0 S1877042815042974 Main PDFcitra89Încă nu există evaluări

- 2010 Van de Pol Et Al Scaffolding in Teacher-Student InteractionDocument27 pagini2010 Van de Pol Et Al Scaffolding in Teacher-Student InteractionLautaro AvalosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment For DiscoveryDocument27 paginiAssessment For DiscoveryDoroteo Ruben ValentineÎncă nu există evaluări

- ftp-2 PDFDocument22 paginiftp-2 PDFMenkheperre GeorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peer LearningDocument7 paginiPeer LearningAndra PratamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Importance of Establishing Relevance in Motivating Student LearningDocument15 paginiThe Importance of Establishing Relevance in Motivating Student LearningIoana MoldovanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Theories PaperDocument4 paginiLearning Theories PaperkimberlyheftyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crosscutting Concepts: Strengthening Science and Engineering LearningDe la EverandCrosscutting Concepts: Strengthening Science and Engineering LearningÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1747938X20302785 MainDocument16 pagini1 s2.0 S1747938X20302785 MainEu Meu MesmoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating New Life Skills As Learning Outcomes in Education Through The Use of Project-Based LearningDocument8 paginiIntegrating New Life Skills As Learning Outcomes in Education Through The Use of Project-Based LearningajmrdÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Student Learn 4Document8 paginiHow Student Learn 4Ainun BadriahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constructivism, Curriculum and The Knowledge QuestionDocument12 paginiConstructivism, Curriculum and The Knowledge Questionbambang riadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student Learning and Academic Understanding: A Research Perspective with Implications for TeachingDe la EverandStudent Learning and Academic Understanding: A Research Perspective with Implications for TeachingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scaffolding Collaborative Case-Based Learning During Research Ethics TrainingDocument24 paginiScaffolding Collaborative Case-Based Learning During Research Ethics TrainingArief Ardiansyah, M.PdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Introduction to CSCL: Gerry Stahl's eLibrary, #15De la EverandGlobal Introduction to CSCL: Gerry Stahl's eLibrary, #15Încă nu există evaluări

- EJ1017519Document12 paginiEJ1017519malika malikaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dthickey@indiana - Edu Gchartra@indiana - Edu Andrewch@indiana - EduDocument34 paginiDthickey@indiana - Edu Gchartra@indiana - Edu Andrewch@indiana - Edud-ichaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cooperative Learn Validated TheoryDocument34 paginiCooperative Learn Validated TheoryMARIA MAGALHAESÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Scientific Method and Scientific Inquiry TensiDocument9 paginiThe Scientific Method and Scientific Inquiry TensiAdi WahyuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behaviorism, Cognitivism, ConstructivsimDocument36 paginiBehaviorism, Cognitivism, ConstructivsimMaheen NaeemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Active Learning Framework and Process of Classroom Engagement A Literature ReviewDocument9 paginiActive Learning Framework and Process of Classroom Engagement A Literature ReviewEditor IJTSRDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personalising Teaching and Learning With Digital Resources: Dial-E Framework Case StudiesDocument17 paginiPersonalising Teaching and Learning With Digital Resources: Dial-E Framework Case StudiesedskjbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insights into Autonomy and Technology in Language TeachingDe la EverandInsights into Autonomy and Technology in Language TeachingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rethinking Curriculum and Teaching: Zongyi DengDocument26 paginiRethinking Curriculum and Teaching: Zongyi DengMaría Dolores García SeguraÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Critical Review and Analysis of The Definitions of Curriculum and The Relationship Between Curriculum and InstructionDocument5 paginiA Critical Review and Analysis of The Definitions of Curriculum and The Relationship Between Curriculum and InstructionNihal100% (1)

- 14963084sandoval Bell Article 1Document4 pagini14963084sandoval Bell Article 1kcwbsgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 paginiAnnotated BibliographyschneidykinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1-Theories of Educational TechnologyDocument32 paginiModule 1-Theories of Educational TechnologyJoevertVillartaBentulanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Running Head: Constructivist Pedagogy: A Review of Literature 1Document6 paginiRunning Head: Constructivist Pedagogy: A Review of Literature 1api-439462191Încă nu există evaluări

- A Deweyan Perspective On Science Education: Constructivism, Experience, and Why We Learn ScienceDocument30 paginiA Deweyan Perspective On Science Education: Constructivism, Experience, and Why We Learn ScienceSaifullah M.AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCCTE Highlight05-ContextualTeachingLearningDocument8 paginiNCCTE Highlight05-ContextualTeachingLearningpindungÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Significance of Motivation in Student-CentredDocument22 paginiThe Significance of Motivation in Student-Centredabir abdelazizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructional Sequence Matters, Grades 9–12: Explore-Before-Explain in Physical ScienceDe la EverandInstructional Sequence Matters, Grades 9–12: Explore-Before-Explain in Physical ScienceÎncă nu există evaluări

- 504learning Theory WritingDocument2 pagini504learning Theory WritingFarnoush DavisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complexity and Curriculum: A Process Approach To Curriculum-MakingDocument14 paginiComplexity and Curriculum: A Process Approach To Curriculum-MakingNana Aboagye DacostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Through Growth MindsetDocument21 paginiLearning Through Growth MindsetNada MahmoudÎncă nu există evaluări

- PhylosopyDocument4 paginiPhylosopyArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABC AssessmentDocument7 paginiABC AssessmentArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivasion in ConstructivisDocument26 paginiMotivasion in ConstructivisArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Model Constructivis TeachingDocument9 paginiModel Constructivis TeachingArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impac Constructivis in PhysicsDocument16 paginiImpac Constructivis in PhysicsArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guiding PracticeDocument7 paginiGuiding PracticeArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7way in ClasroomDocument12 pagini7way in ClasroomArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Examine ConstructivismDocument14 paginiExamine ConstructivismArie Arma ArsyadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Production and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients 5EEC Group 1Document10 paginiProduction and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients 5EEC Group 1Derrick RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cost, Time and Quality, Two Best Guesses and A Phenomenon, Its Time To Accept Other Success CriteriaDocument6 paginiCost, Time and Quality, Two Best Guesses and A Phenomenon, Its Time To Accept Other Success Criteriaapi-3707091100% (2)

- Finite State Machine Based Vending Machine Controller With Auto-Billing FeaturesDocument5 paginiFinite State Machine Based Vending Machine Controller With Auto-Billing FeaturesSubbuNaiduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nikkostirling 2009 CatalogDocument12 paginiNikkostirling 2009 Catalogalp berkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- RC4 Vector Key Based Conditional Access System in Pay-TV Broadcasting SystemDocument5 paginiRC4 Vector Key Based Conditional Access System in Pay-TV Broadcasting SystemAlad Manoj PeterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gen2 ComfortDocument10 paginiGen2 ComfortRethish KochukavilakathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pantaloons FinalDocument30 paginiPantaloons FinalAnkit SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self Priming Water Lifting Booster PumpDocument2 paginiSelf Priming Water Lifting Booster PumpzhelipumpÎncă nu există evaluări

- DPC6HG Aa00 G0000 ZS001 - 001 - 01Document6 paginiDPC6HG Aa00 G0000 ZS001 - 001 - 01rajitkumar.3005Încă nu există evaluări

- Ducon Construction Chemicals Industries LTD - Concrete Admixtures in BangladeshDocument3 paginiDucon Construction Chemicals Industries LTD - Concrete Admixtures in BangladeshFounTech612Încă nu există evaluări

- HP77 Pg84 CouperDocument4 paginiHP77 Pg84 CouperSharjeel NazirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mechanical Braking System of Mine WindersDocument53 paginiMechanical Braking System of Mine WindersAJEET YADAV100% (6)

- Penilaian Kinerja Malcolm BaldridgeDocument24 paginiPenilaian Kinerja Malcolm BaldridgeHijrah Saputro RaharjoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 Golden Rules of Mobile Testing TemplateDocument36 pagini7 Golden Rules of Mobile Testing Templatestarvit2Încă nu există evaluări

- K13 High-Flex Waterproofing SlurryDocument3 paginiK13 High-Flex Waterproofing SlurryAmila SampathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scope of The WorkDocument5 paginiScope of The Worklogu RRÎncă nu există evaluări

- IT Audit Exercise 2Document1 paginăIT Audit Exercise 2wirdinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 5 SupplementsDocument5 paginiChapter 5 SupplementsGabriela MironÎncă nu există evaluări

- C3704 2018 PDFDocument122 paginiC3704 2018 PDFHaileyesus Kahsay100% (1)

- Guide To Port Entry CD: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)Document6 paginiGuide To Port Entry CD: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)Gonçalo CruzeiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- PTRegistrationForm 01 02 2022 - 11 53Document3 paginiPTRegistrationForm 01 02 2022 - 11 53Shiv PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Move All Database Objects From One Tablespace To AnotherDocument2 paginiMove All Database Objects From One Tablespace To AnotherJabras GuppiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topographic Map of NeedvilleDocument1 paginăTopographic Map of NeedvilleHistoricalMapsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Truth About Fuelless Motors Popular Science 1928Document3 paginiThe Truth About Fuelless Motors Popular Science 1928Celestial Shaman100% (2)

- Introduction To Public Health LaboratoriesDocument45 paginiIntroduction To Public Health LaboratoriesLarisa Izabela AndronecÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expansion Indicator Boiler #1Document6 paginiExpansion Indicator Boiler #1Muhammad AbyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practices For Lesson 3: CollectionsDocument4 paginiPractices For Lesson 3: CollectionsManu K BhagavathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competing Values Competency QuestionnaireDocument14 paginiCompeting Values Competency QuestionnaireVahmi Brian Owen D'sullivansevenfoldimerz100% (2)

- 2015 Jicable - Risk On Failure Based On PD Measurements in Actual MV PILC and XLPE Cables.Document3 pagini2015 Jicable - Risk On Failure Based On PD Measurements in Actual MV PILC and XLPE Cables.des1982Încă nu există evaluări

- Cs2000 Universal Translations3006a 50 SGDocument508 paginiCs2000 Universal Translations3006a 50 SGAleksandr BashmakovÎncă nu există evaluări