Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Unit 1 Examiner's Report 2012

Încărcat de

simonballemusicDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Unit 1 Examiner's Report 2012

Încărcat de

simonballemusicDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Examiners Report/ Principal Examiner Feedback Summer 2012

GCE Music Technology 6MT01 Portfolio 1

Edexcel and BTEC Qualifications Edexcel and BTEC qualifications come from Pearson, the worlds leading learning company. We provide a wide range of qualifications including academic, vocational, occupational and specific programmes for employers. For further information visit our qualifications websites at www.edexcel.com or www.btec.co.uk for our BTEC qualifications. Alternatively, you can get in touch with us using the details on our contact us page at www.edexcel.com/contactus. If you have any subject specific questions about this specification that require the help of a subject specialist, you can speak directly to the subject team at Pearson. Their contact details can be found on this link: www.edexcel.com/teachingservices. You can also use our online Ask the Expert service at www.edexcel.com/ask. You will need an Edexcel username and password to access this service.

Pearson: helping people progress, everywhere Our aim is to help everyone progress in their lives through education. We believe in every kind of learning, for all kinds of people, wherever they are in the world. Weve been involved in education for over 150 years, and by working across 70 countries, in 100 languages, we have built an international reputation for our commitment to high standards and raising achievement through innovation in education. Find out more about how we can help you and your students at: www.pearson.com/uk

Summer 2012 Publications Code US032739 All the material in this publication is copyright Pearson Education Ltd 2012

Grade Boundaries Grade boundaries for this, and all other papers, can be found on the website on this link: http://www.edexcel.com/iwantto/Pages/grade-boundaries.aspx

General Introduction The overall impression is that the broad pattern of submissions seen in the last couple of years has again been maintained, with the multi-track recordings being the stronger pieces and the arrangements the weaker. The logs show that centres are making appropriate equipment choices, continuing the trend that has been witnessed across the 2 practical units over the past couple of years. However, candidates must take the time to listen to their mixdowns (ideally on studio monitors rather than headphones). There were still a very high number of submissions with cut beginnings or endings of tracks and a significant number of submissions where tracks listed in the log appear to have been muted in the mix. Sequenced Realised Performance As was the case in previous years, candidates tend to approach this task in one of three ways; those who enter data incorrectly, those who enter it accurately but with a mechanical result, and those who produce a musical performance with editing, shaping and attention to detail. The vast majority of candidates were able to produce realisations of this years stimulus track to a reasonably successful standard, realising the basic elements of the piece but often falling short on the detailed subtleties. More candidates seemed aware that this is predominantly an aural task, with most working quite hard to fill in at least some of the detail not represented by the skeleton score. Similar to last year, most submissions fell within the 21-25 (competent) mark descriptor. However, there were a significant number of candidates who still appear to be working from the given skeleton score and not carefully analysing the track itself. Some candidates struggled to accurately input pitch/rhythm data, leading to performances that were unmusical. Pitch and rhythm Most candidates made at least reasonable attempts to input the pitch and rhythm parts. The varied drum patterns did pose some difficulty, as did the identification of parts not present in the skeleton score. In many instances, pitch errors were due to omissions of repeats rather than inaccurately entered data. These omissions often had a knock on effect on the dynamic changes as such shifts were closely linked to the presence/absence of certain instruments. The final section was a particularly important part of the performance with the added glockenspiel, wind and high synth parts and many candidates struggled to include all of these elements. The higher scoring submissions added in the extra unscored elements and most attempts at doing so were musical.

Common errors included: placing parts (e.g. vocal, backing vocals and synth 3) in the wrong octave (this is easy to do if you are working with changing timbres or entering data from a small MIDI keyboard) Synth 3 not playing at correct points (particularly from bar 37 onwards) Synth 1 playing at inappropriate moments copy/pasting/looping individual errors omitting the glockenspiel, wind noise and high note in the last chorus (these parts were not notated, but were clearly audible in the original) lack of dynamic contrast (particularly in relation to the dynamic lift into the choruses) omitting drum fills and not including the changing drum pattern at bar 49 mis-aligning parts Timbre Many examiners noted that timbre editing appeared to have been more common this year, although in many cases the editing was not entirely successful, with a consequent impact on the success of the mix. The vocal timbre was generally well selected, although a significant number of candidates are still choosing timbres which do not have a sufficient sustaining sound and are difficult to edit (e.g. piano) and are thus hindering their ability to create a musically-shaped line. The quality of responses to question 2 in the logbook has improved and this is very helpful when assessing the extent to which a candidate has worked with the timbres. Balance / Pan As in previous years, candidates who omitted timbres, for example, by missing out a part, failed to access the full marks for this criterion. Many examiners commented on the fact that balance remains an issue in a large proportion of submissions. Specifically, backing vocals were frequently too loud in the mix, or the lead vocal lost. The candidates approach to panning was mixed. Some candidates panned the parts in accordance with the track (Synth 3 is panned left and Synth 4 is panned right in the original AMTV), but too often submissions were very narrow/had no panning at all or were extreme (e.g. lead vocal panned hard left). Musicality Some candidates did attempt to shape the dynamics (especially in the move from verse to chorus) with the success or otherwise being closely linked to whether the presence/absence of parts had been accurately identified. Higher scoring candidates recognised and effectively shaped the dynamic shifts at key points. (Subtle, but noticeable uplift at bar 57; drop in dynamics at bar 73; shift in dynamics at bar 77; crescendo during 2nd half of bar 88 leading to a significant dynamic increase into the final chorus).

Many candidates made at least some attempt at articulation/phrasing, but the majority scored inconsistent. Vocal parts were often over mechanical with little attention paid to the subtleties. The higher scoring candidates shaped the articulation/phrasing effectively with subtle use of pitch bends and modulation. Candidates are reminded to check the score as this again provided valuable guidance as to how parts (particularly the lead vocal) should be shaped. Style/Music technology skills A significant number of candidates seemed to struggle to create a consistent overall sense of style. The errors in timbral editing and lack of attention to dynamics, articulation and phrasing highlighted above were a common cause of this. There were a variety of attempts at the ending, but the majority of candidates were reasonably successful in fading the track. Most candidates are now producing final masters of a good or excellent standard, but there is still a large number of candidates who chop either the start or the end of the track (in all 3 tasks); a careless error that is easily avoided. Candidates are again reminded to study the mark scheme for this part of the task, as there is a reference to chopped beginnings and endings, often ignored. Work should always be checked to ensure that the lead-in and lead-out is not excessive (no more than 5 seconds) and that details such as a reverb tail or the decay of a synth pad are not cut off. Multi-track Recording As in the past, this tended to be the best done of the three tasks. However, many candidates still do not consider the potential practical challenges that can be invoked or avoided by their particular choice of stimulus. Generally, the more successful submissions had clearly selected a piece and arrangement suited to the given recording environment, resources and musicians. In these instances, candidates usually had less corrective work to achieve at the processing stage. Many candidates are still choosing pieces that are beyond the demands of the specification (both in terms of track count and complexity). Whilst there are examples of outstanding work in these cases, more often than not such material proves to be beyond the level of skill demonstrated by most AS Level candidates. On the other hand, there continue to be examples again this year of candidates adopting questionable means with which to meet the task requirements in terms of track and microphone count. Such an approach does not benefit the candidate as, at best, it does not give sufficient scope for candidates to demonstrate their skill level and, at worst, it can lead to a loss of marks. Centres should again note that the following actions will almost certainly lead to a loss of marks:

recording tracks with an inappropriate number of microphones (e.g. two mics on a bass amp) recording only the drum track and bass part of the song whilst still meeting the required number of mics/tracks (thus submitting a song that is regarded as incomplete according to the mark scheme) using the studio software to copy a previously recorded track onto a second track. This does not count as an extra track. The most successful centres continue to be those that keep things fairly simple; vocals, guitars, percussion, DI keyboards are typical examples of instruments that are largely well recorded. Capture This was generally the most successfully achieved aspect of the recordings with most candidates selecting appropriate microphones and positioning them competently. Most centres now seem very aware of the requirements of this task across the mark scheme and, whilst lots of centres do not have access to purpose built recording studios, the use of screens and acoustic panelling is making a very significant difference in many cases. Most candidates demonstrated good awareness of correct microphone technique, level setting and editing, but lack of attention to detailed focus is still a common error. Room ambience continues to be an issue on some recordings which suggests that microphones are not always being effectively positioned. Whilst an increasing number of recordings demonstrated effective noise elimination, background noise could clearly be heard on some recordings (mainly at the start and end of the track). Such noise needs to be edited out (where possible) and a re-recording made where not. Processing This criterion was the section which differentiated a lot of submissions as many candidates did not gain credit due to lack of attention or inconsistent application of effects and processes. The most successful candidates were usually those who had selected appropriate material and scored highly in criterion 1. In these instances, candidates usually had less corrective work to achieve at the processing stage. In terms of EQ, common issues ranged from muddy mixes and booming bass guitars to very harsh electric guitars and dull drum tracks. In many cases it was clear that no EQ had been used when the track would have clearly benefitted from some. Dynamic processing was reasonably well handled (although the choice of song again played a crucial role here). Many candidates struggle to get the lead vocal to sit in the mix, whilst kick drums and bass guitars were often lacking in sufficient control. A significant number of tracks have been overcompressed with pumping an issue - it appears that many candidates have been seeking to master their tracks as loud as possible and have

overdone it. Gating was used by some candidates and this tends to be used reasonably effectively with some exceptions. FX were reasonably well handled. Most mixes showed some attempt to use reverb although its application is often inconsistent. Instruments occupying very different spaces was a common observation made by examiners. Delay is also being increasingly well utilised and there were examples of very effective guitar FX. There are still a number of candidates who are using no reverb at all in an attempt to create a dry contemporary mix. Such misunderstanding leads to the vocal sounding very stuck on and can have a negative impact on the balance and blend as a whole. Conversely, there are other candidates who are applying too much reverb. Balance and blend Many candidates now attain an appropriate sense of balance, although it is still common for particular instruments to be over-favoured in the mix (often electric guitars, vocal or drums). The blending of instruments is more varied with many candidates struggling to fully achieve this aspect. In terms of stereo, most candidates are working quite hard to establish an effective stereo field (there were fewer mono submissions), but some fundamental misjudgements in panning (such as extreme positioning of bass guitar or drum kit elements) remain quite common. Creative Sequenced Arrangement Each year the arrangement has usually been the weakest of the three tasks, many candidates simply adding a backing to the given stimulus. This year, the most popular song was Cant get you out of my head (7580%) and trip hop was the most popular style (75-80%). There were examples of outstanding work across both styles and stimuli with high scoring candidates demonstrating a secure and idiomatic understanding of their chosen style and extensive/convincing development of their chosen stimulus. However, most candidates still take a relatively piecemeal and formulaic approach to developing the musical content of their sequence, often relying on a few stock inventions across some of the criteria from which to construct their arrangement. Use of stimulus Many more submissions seemed to pay closer attention to incorporating the stimulus material in their arrangements although many candidates tended to develop the chosen stimulus in fairly simplistic ways. A lot of the development focussed on melody despite the fact that there was considerable scope for harmonic and rhythmic development in both songs and in both genres. Some candidates chose simple repetition and did not

develop the stimulus in any significant way. The higher scoring candidates demonstrated extensive and convincing development in all aspects. Style/Coherence Most candidates captured the basic essence of their chosen style although a few submissions did not. Many candidates captured the style of the genre, but did not do so with sufficient contrast. There was too much repetition in a significant number of submissions. The more successful candidates had usually approached and achieved the objectives of development of stimulus and style/coherence simultaneously, to achieve more fluid and convincing results in both respects. Use of Music Technology Confidence and control with use of music technology appears to be increasing, with more students using appropriate automation, FX, timbres and showing greater musicality in sequencing skills. In trip hop arrangements, candidates tended to select timbres well, develop appropriate trip-hop style drum loops and achieving a lo-fi production. Samples (such as record crackle, vocal samples and sound effects such as weather) were commonly used to varying degrees of success as were effects such as autopanning, delay, reverb and tremolo. In rock n roll submissions, the timbres were also usually well selected and some dynamic contrast was present. Slap-back delay, chamber-style reverbs and pitch bend/modulation performance techniques were attempted in some submissions, but articulation and phrasing were often ignored and the use of the stereo field was often lacking in others. In both genres a significant number of candidates appeared not to have checked their final recordings for obvious errors, such as cuts/lead outs, which could have been easily rectified. Melody The extent to which melody was developed and added to varied considerably. Many candidates just used the original stimulus with added parts (e.g. bass) and were over repetitive. Some candidates did develop the melody, but attempts were often formulaic and/or inconsistent. The higher scoring candidates developed the given melodic material extensively, adding their own melodic ideas and countermelodies which blended seamlessly with the original material. In rock n roll, the standard of instrumental solos (normally guitar, saxophone or piano) was very good with many being idiomatic. Harmony In trip hop there were some submissions with very good added chords, appropriate key changes and a slowing of the harmonic rhythm, whilst the use of 12 bar blues in Rock n Roll was often very effective, if a little formulaic. However, too often candidates simply used the given stimulus harmony or used new harmony which did not fit with the melody, leading to

uncomfortable passages. Candidates need to think about how they can extend the given harmonic material. Rhythm Many candidates fell into the trap of finding a trip hop drum loop and repeating it throughout their arrangement without any creative development. Similarly, in rock n roll some candidates inputted a swung drum loop and a walking bass with little development. Higher scoring candidates showed considerable rhythmic development in their work as loops were edited and new rhythmic motifs added as the piece progressed. In trip hop, some candidates produced their own loops using their own samples - this was often very effective. In rock n roll, higher scoring candidates made creative use of stops, different drum patterns and rhythmically complex instrumental solos. Texture and Instrumentation There was some good work from many candidates in both genres to produce appropriate textures. However, most candidates submissions did not fully develop the texture to reach the top mark box. Similarly to rhythm, there was too much repetition in many arrangements. Higher scoring candidates created idiomatic textures that maintained interest throughout the piece. Form/structure Most submissions were at least functional in this aspect with some sense of direction. A significant number of submissions simply followed the stimulus, whilst others were excessively repetitive. Higher scoring candidates produced appropriate, but creative structures that built on, but also extended the structure of their chosen stimulus. Candidates need to think about how to bring appropriate structural variety to their arrangements, creating contrast between the different sections. Logbooks Whilst some examiners commented on an improvement in this aspect the logbooks continue to vary in quality considerably. Some submissions included photographs of mic set-ups and screen shots, whilst others gave very little information and contained several blank pages. Where included, photographs of mic positioning proved to be very helpful as they gave an accurate demonstration of the mic setup used. Candidates need to be reminded of the fact that, whilst questions 9 and 10 are the only responses given a mark, the other questions in the log should be approached with care and attention. They are a vital source of information for the examiner who refers to them when marking. If features are not clearly identified they may not receive the full credit they deserve.

In particular, as pointed out in previous years, reference should be made to any editing of the timbres in Task 1A and Task 1C. It is also important to explain clearly the mics used and the tracks to which they relate in Task 1B. Settings of processors should be included in the track sheets. Many examiners commented on an overall improvement in the answers to questions 9 and 10, but the quality of responses remains very varied. Some candidates are missing out on further credit here. Centres are reminded that it is worth 20 marks and that the answers can be thoroughly prepared before writing up. Many candidates submissions fail to score highly in this aspect and it can have a very significant effect on their overall result for Unit 1. Question 9 This question requires the candidate to explain how the arrangement was developed from the stimulus. There is still a tendency for too many candidates to focus on the development of their style, rather than the stimulus, which inevitably impacts the credit that can be awarded. Many candidates did not refer to the stimulus in any detail in their answers. The more successful responses usually provided specific detail (bar/time references, chord/note names, section descriptions) and demonstrated correct use of musical or technical terminology, to indicate clearly their intentions and rationale when developing the stimulus. Question 10 This question requires the candidate to correctly identify the stylistic features of the chosen style and explain how these are used in the arrangement. Most students appear to be conducting some research around their chosen genre, but many still rely on a simplistic or generalised understanding of a few stylistic rudiments. Common shortcomings involved vague generalisations (such as descriptions of trip hop as having a 'chilled out feel'). Candidates need to focus on being as specific as possible when commenting on how they have included key features in their arrangement. It is not sufficient to write trip hop uses samples so I have used samples. Detail is required for full credit including reasons for choice, details of samples used and examples of trip hop artists and songs that used similar samples. Higher scoring responses demonstrate breadth of listening with reference to specific tracks/artists. They show a more sophisticated appreciation of the specific subtleties of the genre, linking this understanding clearly to specific features of their own arrangement (often using time or bar references, where useful).

Administration The overwhelming majority of centres submitted work on time and complete. However, some centres failed to pack the CDs adequately so that they arrived broken. In other cases work had not been thoroughly checked before sending to the examiner. A few CDs were blank or contained only data, whilst there were also a few instances of recordings in which the original was audible in the candidates submission. The most likely explanation for this is that it was used as a guide track and not erased before the final mix. In such cases, it is vital that centres respond to requests for replacement work from examiners promptly. Whilst it is understood by the examining team that CD errors do occur, all CDs should be checked for playback in a standard CD player (not computer CD drive). If candidates are wanting to submit additional sheets in their logbook these should be clearly labelled with candidate name, number and centre name/number, put in the booklet in the right place and secured with a treasury tag/staples. It is important for centres to retain back-up material. Centres should refer to the Administrative Support Guide (formerly Instructions for the Conduct of the Examinations document) that is available on the GCE Music Technology website under Assessment Materials/ Instructions for the Conduct of the Examinations.

Further copies of this publication are available from Edexcel Publications, Adamsway, Mansfield, Notts, NG18 4FN Telephone 01623 467467 Fax 01623 450481 Email publication.orders@edexcel.com Order Code US032739 Summer 2012

For more information on Edexcel qualifications, please visit www.edexcel.com/quals

Pearson Education Limited. Registered company number 872828 with its registered office at Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- As Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Document20 paginiAs Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Hannah Louise Groarke-YoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- July IV 2012 Concert FinalDocument1 paginăJuly IV 2012 Concert FinalsimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- As Trial Recording Task GenericDocument2 paginiAs Trial Recording Task GenericsimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The History of CompressionDocument4 paginiThe History of Compressionsimonballemusic100% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- As Trial Recording Task GenericDocument2 paginiAs Trial Recording Task GenericsimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Document12 paginiA2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Hannah Louise Groarke-YoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- As Music Tech. Logbook 2011 TemplateDocument11 paginiAs Music Tech. Logbook 2011 TemplatesimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Music Department Work PlanDocument6 paginiMusic Department Work PlansimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drum and Bass RevisionDocument3 paginiDrum and Bass Revisionsimonballemusic100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

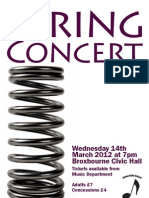

- Spring 2012 ConcertDocument2 paginiSpring 2012 ConcertsimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Diatonic Melody FragmentsDocument1 paginăDiatonic Melody FragmentssimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- A Revolution in Pop Music - 1960sDocument3 paginiA Revolution in Pop Music - 1960ssimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Diatonic Harmony 1Document1 paginăDiatonic Harmony 1simonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The 1980s: New WaveDocument7 paginiThe 1980s: New WavequartalistÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Intro MidiDocument16 paginiIntro Midiwizard_of_keysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Unit 4 Composition Written Account TemplateDocument5 paginiUnit 4 Composition Written Account TemplatesimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tips From A Mastering EngineerDocument2 paginiTips From A Mastering EngineersimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Development of Technology-Based Music 1 - Synths & MIDIDocument6 paginiThe Development of Technology-Based Music 1 - Synths & MIDIsimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Late 1960s: You Can Do What You Want ToDocument4 paginiThe Late 1960s: You Can Do What You Want TosimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of RecordingDocument6 paginiHistory of RecordingMatt Gooch0% (1)

- Distribution FormatsDocument2 paginiDistribution Formatsmws_97Încă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Concert Details For ParentsDocument7 paginiConcert Details For ParentssimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Development of Technology-Based Music 3 - InstrumentsDocument5 paginiThe Development of Technology-Based Music 3 - Instrumentssimonballemusic100% (1)

- Rock and RollDocument3 paginiRock and RollsimonballemusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Midi Leaflet 3Document6 paginiMidi Leaflet 3domparker1234Încă nu există evaluări

- I Hate Breakcore TutorialDocument16 paginiI Hate Breakcore TutorialΣταυρος ΚωνσταντακηςÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Electronicus Patch Book - 0Document12 paginiElectronicus Patch Book - 0koutouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Making Music With MATLABDocument4 paginiMaking Music With MATLABAndrei BurlacuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buchla Music Easel ManualDocument68 paginiBuchla Music Easel Manualchloe_stamperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geist2 Operation Manual PDFDocument152 paginiGeist2 Operation Manual PDFGeorge RobinsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- LK100 ManualDocument40 paginiLK100 ManualReggie DonaldsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 100 Greatest Horror SoundtracksDocument131 paginiThe 100 Greatest Horror SoundtracksmagusradislavÎncă nu există evaluări

- CineStrings CORE ManualDocument23 paginiCineStrings CORE ManualPiotr Weisthor RóżyckiÎncă nu există evaluări

- GP 328Document272 paginiGP 328rickyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alesis QS71 QS81 ManualDocument188 paginiAlesis QS71 QS81 ManualJeremy CanonicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blue Lion Biotech - DR Oligo BrochureDocument10 paginiBlue Lion Biotech - DR Oligo BrochuretynieredwineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Autonomous Instruments PDFDocument404 paginiAutonomous Instruments PDFdanepozziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roland SH-32 Owners ManualDocument124 paginiRoland SH-32 Owners ManualHumberto HumbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sound On Sound UK - April 2023Document164 paginiSound On Sound UK - April 2023Dan Alexandru100% (1)

- Analog Four Notebook 1v50aDocument308 paginiAnalog Four Notebook 1v50aWQDSQWÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- JUNO-DS ParamGuide E01 WDocument365 paginiJUNO-DS ParamGuide E01 WDenilson TecladistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sound Design TipsDocument3 paginiSound Design TipsAntoine100% (1)

- M49 Operation ManualDocument34 paginiM49 Operation ManualmarcosherreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The EX5 Arpeggiator - Brian CowellDocument7 paginiThe EX5 Arpeggiator - Brian CowelljboltnzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Addendum: Software Version 4Document51 paginiAddendum: Software Version 4Ateeb AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Release NotesDocument9 paginiRelease Notes김준우Încă nu există evaluări

- Contents Beat Making On The Mpc5000Document12 paginiContents Beat Making On The Mpc5000Slip-stream0% (1)

- Pizazz ManualDocument8 paginiPizazz ManualLeandro PachecoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beck M., Geoghegan R. The Art of Proof.. Basic Training For Deeper Mathematics (Springer, 2010)Document20 paginiBeck M., Geoghegan R. The Art of Proof.. Basic Training For Deeper Mathematics (Springer, 2010)tele6Încă nu există evaluări

- Patches For Zoom 505Document6 paginiPatches For Zoom 505Octavio FigueroaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Voice MorphingDocument23 paginiVoice Morphingapi-374496383% (6)

- Garageband Quick Start Guide Version 2.0Document41 paginiGarageband Quick Start Guide Version 2.0Esteban VarasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aeternus Brass VST, VST3, Audio Unit Plugins: Virtual Trumpet, Trombone, Tuba, French Horn, Flugelhorn, Cornet, Brass Sections, Orchestral Ensemble and Classic Analog Synthesizer Brasses. EXS24 + KONTAKT (Windows, macOS)Document18 paginiAeternus Brass VST, VST3, Audio Unit Plugins: Virtual Trumpet, Trombone, Tuba, French Horn, Flugelhorn, Cornet, Brass Sections, Orchestral Ensemble and Classic Analog Synthesizer Brasses. EXS24 + KONTAKT (Windows, macOS)Syntheway Virtual Musical Instruments0% (1)

- Prokeys 88Sx: User GuideDocument21 paginiProkeys 88Sx: User GuideWilson CamargoÎncă nu există evaluări