Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Concerning The Visual in Poetry

Încărcat de

TampiperinTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Concerning The Visual in Poetry

Încărcat de

TampiperinDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

No.

2 August 22, 2005

direct poetics

8630 Wardwell Road, Bainbridge Island WA 98110, Drew Kunz, ed.

Guy Bennett Concerning the Visual in Poetry

2005, Guy Bennett

I once found myself not reading a book but staring at the letters. gerard unger

ou could say that all written poetry is inherently visual, and this is certainly true. Not of poetry alone, however, but of all instances of written language. You could argue that the multiform nature of the poetic text as opposed to the more uniform appearance of written prose tends to emphasize the visual qualities of poetry. This is certainly true as well, though it is a question of form, not ontology, and visual poetry is not a poetic form but a form of poetry. In a broad sense, the term visual poetry can be understood to mean any poetry that accords obvious signicance to the visual aspect of the poem. The abstract poem, the calligram, the concrete poem, the constellation, the druksel, the elementary poem, the evident poem, the ferro-concrete poem, the free-word poem, the ideogram, the kinetic poem, the lettrist poem, the mechanical poem, the optical poem, the opto-phonetic poem, the painting poem, the pattern poem, the plastic poem, the poster poem, the symbiotic text, the tiksel, the typewriter poem, the typoem, the typogram, and the zeroglyph are all types of visual poetry, though the terms are far from interchangeable. To paraphrase Mary Ellen Solt, so many kinds of experimental poetry are being labeled visual that it is difcult to say what the word means (Solt, 7). In a more restricted, and thus more precise and useful sense, the term visual poetry refers to a particular kind of visual poetry, one that owered in the 1950s and 60s, but was no longer practiced with any regularity after the early 1970s. Its specicity resides in the emphasis placed on the graphic nature of the printed or written sign, which is brought so predominantly to the fore that it occludes the semantic potential of that sign by obviating any linguistic context in which it might signify something were it only a sound thus radically reducing, if

not altogether eliminating the possibility of conventional linear reading, that is, ultimately, reading for meaning. It follows that the visual poem, in this more specic sense, is inherently meaningless. Unburdened by the conceptual weight of signiers, signieds, and other such symbolic clap-trap, it is but itself: an autonomous (i.e. non-referential), aesthetically organized instance of written language. It ignores the guration of concrete poetry and the calligram and, needless to say, has little if anything to do with the traditional linear poem articulated spatially whether lexically or phraseologically, formally or typographically on the page. Visual poetry in this sense is the subject of the present essay. Schwitters once wrote: Not the word but the letter is the original material of poetry. Were I to rephrase that statement for the purposes of the present essay, I would say that the letter form is the original material of visual poetry, and the study of the visual poem might very well begin by considering the position the poet takes vis--vis the letter form. At its most minimal, the visual poem has as both its point of departure and nal destination the letter shape, though it is rare that a poem consist of a single sign.1 More often than not, multiple instances of a given letter are assembled into an abstract composition that plays on the graphic structure of the letter form, perhaps the most characteristic example being Hansjrg Mayers 196263 collection alphabet.2 In these poems (gs. 1, 2 and 3), Mayer combines letter forms according to their structural logic (i.e. their horizontal, vertical and/or diagonal strokes, their curves and counters, etc.), creating purely visual compositions. They are compact, asemantic works that explore the structural relationships of letter forms and the amalgams those combined forms create against the white space of the page. They do not seek to activate any potential meanings the letter shapes may have individually, nor any they may take on when organized into a poem. Mayer, as Stephen Bann has written, is not concerned with meaning: the letters which he uses are not so much legible as supremely visible. The signicance of his work lies in the fact that he uses the printed letter quite simply as a material. (Bann, 11)

fig. 1

fig. 2

fig. 3

In contrast, let us consider a concrete poem by Ladislav Novk (g. 4). It, too, is formed from a single sign, but as is generally the case in concrete poetry, the semantic potential of that sign is brought into play. individualista is essentially a visual pun. Its humor results from the complex of meanings at work in the poem, and which (as is often true of concrete poetry) convey a relatively obvious, essentially didactic message in this case: Dont conform. Such semantic play is entirely lacking in Mayers poems as they do not pretend to meaning. They are strictly visual, semantically transparent works ideograms unencumbered by ideas and they operate in the free eld of graphic form and color. They are minimalistic, even excessively so, whereas most visual poetry tends toward a richer typographic palate comprising multiple letter and analphabetic forms, often in combination with basic geometric shapes. For example, e o by Ernst Jandl (g. 5) is characterized by a structural tension created by the juxtaposition of the roundness of those three letters and the conicting triangular and square shapes they combine to form. Furthermore, the two-dimensional poem cleverly suggests visual depth and translucence through strictly typographical means: the square appears to be set in front of the triangle, the crossbar of the e creating a darker color than that of the o with its open counter. The square, as if transparent, lets the darker color of the triangle show through, so to speak, giving a median color created by the accented . The resulting gradation of typographic color evokes the parallel phonetic gradation of those letters, being roughly equivalent to o and e pronounced together, as demonstrated in the homophonous ligature . The visual poetry of John Furnival is more elaborate still as it combines a broad range of letter forms into a more intricate whole. As a result of overprinting, many of the letter shapes are obscured, thus limiting our reading of the poem to the recognition of its constituent elements, and the way in which they are combined to create the composition. In Furnivals work, there is frequently an underlying geometric structure which is created by repeating and displacing groups of letters around a central axis, producing an intricate pattern reminiscent of Islamic art, with its tendency to geometric abstraction (g. 6).

fig. 4

fig. 5

fig. 6

Text 1 by Fernando Milln (g. 7) also creates a strong graphic effect through the use of the black rectangle that dominates the work, giving the poem its elongated shape and generating diversity in color and texture by contrasting with the letter forms below. The latter are themselves combined into a rectangle of nearly identical proportions, resulting in a symmetrical composition. The use of simple punctuation symbols along with the letters creates variety and sets up a visual rhythm, the square dots of the exclamation point, colon, periods and I breaking up the already fractured white space and contrasting with the round counters of the p, b and d. Text 1 recalls the work of certain poet/artists of the historical avant-garde, most notably Hendrik Werkman, who produced a striking body of visual poetry for the most part, painterly assemblages of letter forms, rules and/or simple, geometric shapes (gs. 8 and 9). Much of his work, printed in color, oats somewhere between poetry and painting. It fig. 8 pregures the visual poetry of the 1950s and 60s in its singleminded exploration of the inner logic of graphic forms. A similar atmosphere pervades the work of Giovanna Sandri, a poet remarkable for her graceful sense of abstraction and carefully balanced compositions. Her frequent, at times exclusive use of analphabetics (gs. 10 and 11) virtually removes her graphic work from any linguistic context whatever, giving it a stark, mute quality. The poems of her rst

fig. 7

fig. 9

fig. 10

fig. 11

book, Capitolo zero [Chapter Zero 1969], seem as does much of her visual poetry, a writing without a speaking, as if the poems issued from some preverbal language whose roots reach back beyond vocally articulated sound, as the title of the book suggests.3 Though effectively devoid of typical poetic devices, much visual poetry is in fact informed by traditional versication and rhetoric. The third poem by Sandri (g. 12), for example, brings into play a number of conventional poetic techniques. There is what could be termed visual rhyme in the repeated letters m, , and g, a sense of form and analogy in the recurrence of certain graphic shapes (the vertical rule and the columns of ms, the closed parenthesis and the right side of the 0 to the left, the round eye of the a and the gs below, not to mention the staccato-like punctuation of the ), and a swift, choppy rhythm set up by the strong vertical emphasis and repetitive letter and graphic shapes that guide the readers eye through the poem. When letter forms are used, as they are here, as autonomous graphic elements, the physical nature of writing is brought bluntly to the fore, and certain poets have taken this approach to an extreme, basing their work on the materiality of the sign as written/printed on paper. The resulting poetry is unique in that it activates not only the graphic sign itself, but the paper on which it is printed, and which, as a material object, can be physically apprehended and manipulated, as well. Poets like Franz Mons (g. 13) and Adriano Spatola (gs. 14 and 15) have crumpled, cut up, fragmented and reassembled poems, producing a shattered graphic discourse that borders on optical static. Spatola in particular consistently pushed the boundaries of visual poetry, and his zeroglyphics, as he called them, represent a limit beyond which written language virtually ceases to exist, for in these poems the letter form is so fragmented as to be 4 unrecognizable as such. In an essay on Spatolas zeroglyphics, Giulia Niccolai has commented: Zeroglyphic stems of course from the word hieroglyphic, and we know that hieroglyphic derives from the old Latin hieroglyphicum, from the Greek hieroglyphicos i.e. pertinent to the sacred (from hieros) incisions (from the verb glyphein, to incise, to sculpt) and thus conveys the annulment of the semantic message and the presence of the iconic one.

fig. 12

fig. 13

fig. 14

The annulment of the semantic message, I have argued, constitutes the very specicity of visual poetry, though some might complain that it also represents its major aw, as one might justiably ask: is this really poetry at all? Can we accept a poem wholly devoid of semantic content? A writing that refutes interpretation? The answer, of course, is yes. There is a long tradition of semantically obscured or transparent poetry. One thinks of folk poetry and nursery rhymes, with their frequently meaningless turns and refrains, the French fatrasie of the Middle Ages, the nonsense poetry of 19th century writers like Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear, not to mention the sound poetry of such luminaries of the historical avant-garde as Ball, Huelsenbeck, Khlebnikov, and Kruchenykh, to name just a few. Nor should we forget that visual poetry, as dened here, is a product of the rst decades of the 20th century and was practiced by a number of poets, among them Marinetti, Pietri, Schwitters and Werkman. As Paul de Vree has written: [Visual poets] still adhere to the notion of poetry because through the text however rudimentary, reduced or truncated they are confronted with an optical process. The text remains primary. (klankteksten, p. 9). I would add that poetry, whose medium is language, begs an exploration of all aspects of that medium, and should in no way be limited or bound to that part which bears meaning. It seems self-evident that poets would investigate and exploit the potential of written language in their work, as it is in and through writing that poetry is generally conveyed and, in a broader sense, language eternalized. And to quote Schwitters again: Eternal lasts longest.

fig. 15

notes 1 Rare but not unknown: Vasilisk Gnedovs 1913 collection [Death to Art] includes two one-letter poems, which may well be the rst examples of this minimalist genre. In the early 1920s Schwitters himself wrote at least two one-letter poems, das w-gedicht [the w-poem] and das igedicht [the i-poem]. In neither case can these texts be considered visual poetry as dened here, however, since Gnedovs poems play on the meanings of the letters in question and Schwitters on their sound (he would recite them in his public performances). 2 alphabet by Hansjrg Mayer was reprinted in 2002 by Seeing Eye Books. 3 A number of the visual poems from Capitolo zero were recycled by Sandri in her Clessidra: il ritmo delle trace [Hourglass: The Rhythm of Traces] from 1994, where they were paired with verbal texts written in Italian. This work was published in a facsimile English edition in 1998 by Seeing Eye Books. 4 From A Possible Way of Interpreting Some Zeroglyphics, Niccolais afterword in Adriano Spatolas Zeroglyphics (Los Angeles and Fairfax: Red Hill Press, 1977), translated by Niccolai and Paul Vangelisti. (Unpaginated) Seeing Eye Books will reprint this collection in 2006.

This essay was originally published in Witz vi.3 (Spring 1999). It appears here in a slightly revised form.

select bibliography Bann, Stephen, ed. Concrete Poetry: an international anthology. London: London Magazine Editions, 1967. dOrs, Miguel. El Caligrama, de Simmias a Apollinaire: Historia y antologa de una tradicin clsica. Baraain-Pamplona: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra, 1977. klankteksten ? konkrete pozie visuele teksten. Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 1971. Peignot, Jrme. Typosie. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale Editions, 1993. Solt, Mary Ellen, ed. Concrete Poetry: A World View. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1968. Spatola, Adriano, and Giovanni Fontana, eds. oggi poesia domani: rassegna internazionale di poesia visuale e fonetica. Fiuggi: Biblioteca comunale, 1979. . Verso la poesia totale. Torino: G.B. Paravia & C., 1978.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Mary Ellen Solt Concrete Poetry A World ViewDocument91 paginiMary Ellen Solt Concrete Poetry A World Viewzezi bon100% (2)

- Concrete Poetry Revolution Begins in BrazilDocument42 paginiConcrete Poetry Revolution Begins in BrazilHend KhaledÎncă nu există evaluări

- LOVE Art Politics Adrienne Rich InterviewsDocument10 paginiLOVE Art Politics Adrienne Rich Interviewsmadequal2658Încă nu există evaluări

- Field Writing As Experimental PracticeDocument4 paginiField Writing As Experimental PracticeRachel O'ReillyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bernadette Meyaer Poems in EnglishDocument7 paginiBernadette Meyaer Poems in EnglishOlga NancyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foss Genreric Criticism - JPG PDFDocument5 paginiFoss Genreric Criticism - JPG PDFsmall_chicken_9xÎncă nu există evaluări

- Save paper and follow @newyorker on Twitter for updates on "Unmournable BodiesDocument4 paginiSave paper and follow @newyorker on Twitter for updates on "Unmournable BodiesGaby ArguedasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Divya Victor's Cicadas in The Mouth Leslie Scalapino LectureDocument9 paginiDivya Victor's Cicadas in The Mouth Leslie Scalapino LectureRobinTMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trisha Donnelly Exhibition PosterDocument2 paginiTrisha Donnelly Exhibition PosterThe Renaissance SocietyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allen Ginsberg. Independence Day ManifestoDocument3 paginiAllen Ginsberg. Independence Day ManifestoNicolásMagarilÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Charles Bernstein) Close ListeningDocument401 pagini(Charles Bernstein) Close ListeningKatie Banks100% (3)

- The Step Not BeyondDocument162 paginiThe Step Not BeyondTimothy BarrÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Art of ArtificeDocument37 paginiThe Art of ArtificeDean WilsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joris, Pierre - Excerpts From Paul Celan - MicrolithsDocument5 paginiJoris, Pierre - Excerpts From Paul Celan - MicrolithsBurp FlipÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virginia Woolf - The Death of The MothDocument4 paginiVirginia Woolf - The Death of The MothGuadao94Încă nu există evaluări

- Where Everything Is in Halves, by Gabriel Ojeda-SagueDocument22 paginiWhere Everything Is in Halves, by Gabriel Ojeda-SagueBe About It Press100% (1)

- Lori Emerson Reading Writing InterfacesDocument248 paginiLori Emerson Reading Writing Interfacesdianacara9615Încă nu există evaluări

- Poetic Realism by Rachel Blau DuPlessis Book PreviewDocument19 paginiPoetic Realism by Rachel Blau DuPlessis Book PreviewBlazeVOX [books]Încă nu există evaluări

- Underglazy: Oki SogumiDocument30 paginiUnderglazy: Oki SogumiOkiSogumiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manguel - A Brief History of The Page PDFDocument4 paginiManguel - A Brief History of The Page PDFAnonymous HyP72JvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asemic WritingDocument2 paginiAsemic WritingAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- MILLER, C. R. (1984) - Genre As Social Action.Document18 paginiMILLER, C. R. (1984) - Genre As Social Action.Celso juniorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Love For Sale PDFDocument2 paginiLove For Sale PDFchnnnna100% (1)

- Mexican Literature in The Neoliberal EraDocument14 paginiMexican Literature in The Neoliberal EraEliana Hernández100% (1)

- Brian Kim Stefans. Conceptual Writing: The L.A. Brand. 2014Document16 paginiBrian Kim Stefans. Conceptual Writing: The L.A. Brand. 2014romanlujanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stephen Fredmans - Em-Poets Prose - The Crisis in American VerseDocument9 paginiStephen Fredmans - Em-Poets Prose - The Crisis in American VerseJoxarelis MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LIPPARD, Lucy - Get The Message - A Decade of Art For Social Change PDFDocument169 paginiLIPPARD, Lucy - Get The Message - A Decade of Art For Social Change PDFGuilherme Cuoghi100% (2)

- Allen Ginsberg - Taking A Walk Through Leaves of GrassDocument43 paginiAllen Ginsberg - Taking A Walk Through Leaves of Grassagrossomodo100% (1)

- Leslie Hill Distrust of Poetry Levinas Blanchot CelanDocument24 paginiLeslie Hill Distrust of Poetry Levinas Blanchot CelanManus O'DwyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study Guide for Lyn Hejinian's "yet we insist that life is full of happy chance"De la EverandA Study Guide for Lyn Hejinian's "yet we insist that life is full of happy chance"Încă nu există evaluări

- P. Adams Sitney - Poética de BrakhageDocument69 paginiP. Adams Sitney - Poética de BrakhageCamila RiosecoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interbred and Intertwined - Collage Montage and The Trouble With TerminologyDocument7 paginiInterbred and Intertwined - Collage Montage and The Trouble With TerminologyAlexCosta1972Încă nu există evaluări

- Howtogofrom Anne BoyerDocument8 paginiHowtogofrom Anne BoyerFederica BuetiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drawing Out A New Image of Thought: Anne Carson's Radical EkphrasisDocument12 paginiDrawing Out A New Image of Thought: Anne Carson's Radical EkphrasisMilenaKafkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Małgorzata Stępnik, Outsiderzy, Mistyfikatorzy, Eskapiści W Sztuce XX Wieku (The Outsiders, The Mystifiers, The Escapists in 20th Century Art - A SUMMARY)Document6 paginiMałgorzata Stępnik, Outsiderzy, Mistyfikatorzy, Eskapiści W Sztuce XX Wieku (The Outsiders, The Mystifiers, The Escapists in 20th Century Art - A SUMMARY)Malgorzata StepnikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unexplained Presence by Tisa BryantDocument10 paginiUnexplained Presence by Tisa BryantAlesandroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poetry in Pieces: César Vallejo and Lyric ModernityDe la EverandPoetry in Pieces: César Vallejo and Lyric ModernityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aphoristic Lines of Flight in The Coming Insurrection: Ironies of Forgetting Yet Forging The Past - An Anamnesis For George Jackson1Document29 paginiAphoristic Lines of Flight in The Coming Insurrection: Ironies of Forgetting Yet Forging The Past - An Anamnesis For George Jackson1Mosi Ngozi (fka) james harrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Are The Poets For - Bruns PDFDocument124 paginiWhat Are The Poets For - Bruns PDFTheodoros Chiotis100% (4)

- Filliou SamplerDocument19 paginiFilliou SamplerCorpo EditorialÎncă nu există evaluări

- María Rosa Menocal - Shards of Love - Exile and The Origins of The Lyric (1993, Duke University Press) - Libgen - LiDocument193 paginiMaría Rosa Menocal - Shards of Love - Exile and The Origins of The Lyric (1993, Duke University Press) - Libgen - Libagyula boglárkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hugo García Manríquez, "Anti-Humboldt" (English)Document5 paginiHugo García Manríquez, "Anti-Humboldt" (English)jenhofer100% (1)

- Grammar, Ghosts, and the Limits of African PerformanceDocument7 paginiGrammar, Ghosts, and the Limits of African PerformanceDaniel Conrad100% (2)

- The Avant-Garde BookDocument19 paginiThe Avant-Garde Bookjosesecardi13Încă nu există evaluări

- Rooms and Spaces of ModernityDocument232 paginiRooms and Spaces of ModernityAndreea Moise100% (1)

- Celebrating The 125th Anniversary of Mallarmé's "Un Coup de Dés"Document12 paginiCelebrating The 125th Anniversary of Mallarmé's "Un Coup de Dés"rbolickjrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forgetting To Remember: From Benjamin To BlanchotDocument20 paginiForgetting To Remember: From Benjamin To BlanchotAmresh SinhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A5m WecpDocument98 paginiA5m WecpStacy HardyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maurice Blanchot-The Unavowable CommunityDocument47 paginiMaurice Blanchot-The Unavowable Communityj aÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, and Language PoetryDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, and Language PoetryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Think - On ItDocument5 paginiThink - On Itz78kidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legends of The Warring Clans, Or, The Poetry Scene in The NinetiesDocument226 paginiLegends of The Warring Clans, Or, The Poetry Scene in The Ninetiesandrew_130040621100% (1)

- Modernist Miniatures. Literary Snapshots of Urban Spaces, A. HuyssenDocument16 paginiModernist Miniatures. Literary Snapshots of Urban Spaces, A. HuyssenPatricia LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- You Who Never Arrived Poem AnalysisDocument1 paginăYou Who Never Arrived Poem Analysissoho87100% (1)

- UntitledDocument4 paginiUntitledTampiperinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dwiggins MssByWadDocument171 paginiDwiggins MssByWadTampiperinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leica IiifDocument123 paginiLeica Iiifmusashi47Încă nu există evaluări

- How I Did Not Write Some of My Books: An Appropriation LexiconDocument11 paginiHow I Did Not Write Some of My Books: An Appropriation LexiconTampiperinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guy Bennett: Some Thoughts About The Chapbook On The Tenth Year of Publishing Seeing Eye BooksDocument8 paginiGuy Bennett: Some Thoughts About The Chapbook On The Tenth Year of Publishing Seeing Eye BooksBéatrice MousliÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Yorkshire dialect from Anglo-Saxons to modern dayDocument2 paginiHistory of Yorkshire dialect from Anglo-Saxons to modern dayArtem BezruchkoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test Bank For Human Communication 7th Edition by Judy Pearson Paul Nelson Scott Titsworth Angela Hosek 3Document7 paginiTest Bank For Human Communication 7th Edition by Judy Pearson Paul Nelson Scott Titsworth Angela Hosek 3anselmanselmgyjdddÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Rhetorical AnalysisDocument2 paginiLesson Plan Rhetorical Analysisapi-403618226Încă nu există evaluări

- Guidance For Delivery Level 2 Writing v1 0 PDF - AshxDocument20 paginiGuidance For Delivery Level 2 Writing v1 0 PDF - Ashxquantumquasar86Încă nu există evaluări

- Letter Writing Guide: Tips for Formal and Personal CorrespondenceDocument34 paginiLetter Writing Guide: Tips for Formal and Personal CorrespondencesyedmuzammilaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tdiljan 2002Document94 paginiTdiljan 2002utpalrguÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Farmer and The Crane: Moral of The Story: Bad Company Is HarmfulDocument4 paginiThe Farmer and The Crane: Moral of The Story: Bad Company Is HarmfulSamiul AhsanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 关于汉字学习的顺序Document15 pagini关于汉字学习的顺序JOLINÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Communication ModelDocument14 paginiA Communication Modelrace_perezÎncă nu există evaluări

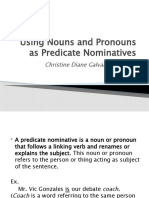

- Using Nouns and Pronouns As Predicate NominativesDocument9 paginiUsing Nouns and Pronouns As Predicate NominativesChristine DianeÎncă nu există evaluări

- What makes text a connected discourseDocument11 paginiWhat makes text a connected discourseshinÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Completed) Navigate Intermediate B1+ Coursebook (Teacher's Edition)Document241 pagini(Completed) Navigate Intermediate B1+ Coursebook (Teacher's Edition)PabloVicari65% (26)

- Sociolinguistic Style: A Multidimensional Resource For Shared Identity CreationDocument23 paginiSociolinguistic Style: A Multidimensional Resource For Shared Identity Creationn0tsewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 2 Lesson 10: Chocolate Milk for DannyDocument112 paginiUnit 2 Lesson 10: Chocolate Milk for DannyGlenn LelinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wiley Journals Style Manual PDFDocument118 paginiWiley Journals Style Manual PDFKoellieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design An Interactive Educational Lesson Following The AddieDocument51 paginiDesign An Interactive Educational Lesson Following The Addieapi-713127363Încă nu există evaluări

- AMSIB Reporting Guidelines 2022-2023Document17 paginiAMSIB Reporting Guidelines 2022-2023Emre-Mihai YapiciÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation A: Grammar 1 Underline The Correct Word(s)Document5 pagini2 Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation A: Grammar 1 Underline The Correct Word(s)Алина100% (1)

- Elementary Unit 11Document13 paginiElementary Unit 11andres lÎncă nu există evaluări

- Present Continuous (2019)Document4 paginiPresent Continuous (2019)Àgora Aula de repàsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communicative Comp RefDocument2 paginiCommunicative Comp RefLynnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Get Involved American Edition Level Intro Workbook Unit 4Document5 paginiGet Involved American Edition Level Intro Workbook Unit 4KeilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Difference in Malaysian and English Word FormationDocument10 paginiDifference in Malaysian and English Word Formationamzar rifqiÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Use Global English Books PDFDocument10 paginiHow To Use Global English Books PDFHuynhtrunghieuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learn Animals Names SongDocument9 paginiLearn Animals Names SongMelania AnghelusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship Development Plan TemplateDocument3 paginiInternship Development Plan Templatelephuthanh02Încă nu există evaluări

- The Pragmatic Structure of Written AdvertismentsDocument9 paginiThe Pragmatic Structure of Written AdvertismentsSuzana SterjovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tibetan Calligraphy Copybook in The Uchen, Tsuring and Chuyig StylesDocument10 paginiTibetan Calligraphy Copybook in The Uchen, Tsuring and Chuyig StylesElena SermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hentai Kanbun Word Order Patterns in Old JapaneseDocument16 paginiHentai Kanbun Word Order Patterns in Old JapaneseeskriptumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morphology in Greek Linguistics A StateDocument42 paginiMorphology in Greek Linguistics A StateΧρήστος ΡέππαςÎncă nu există evaluări