Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Experiential Liberation

Încărcat de

oana liminalaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Experiential Liberation

Încărcat de

oana liminalaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

J Contemp Psychother (2007) 37:3339 DOI 10.

1007/s10879-006-9032-y

ORIGINAL PAPER

The Experiential Liberation Strategy of the Existential-Integrative Model of Therapy

Kirk J. Schneider

Published online: 23 February 2007 C Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2007

Abstract This article summarizes the experiential liberation strategy of the existential-integrative (EI) model of therapy. The existential-integrative model of therapy provides one way to understand and coordinate a variety of intervention modes within an overarching ontological or experiential context. I will (1) dene the experiential liberation strategy such as its emphasis on the capacities to constrict, expand, and center psychophysiological capacities; (2) describe its salient featuressuch as the four stances that promote experiential liberation: presence, invoking the actual, vivifying and confronting resistance, and the cultivation of meaning and awe; and (3) illustrate the relevance of the strategy to case vignettes drawn from actual practice. Keywords Experiential . Existential . Psychotherapy

This article provides an overview of the experiential liberation strategy of the existential-integrative (EI) model of therapy I developed with the collaboration and inspiration of Rollo May and James Bugental (Schneider & May, 1995; Schneider, 1998, 2003). EI therapy is one way to understand and coordinate a variety of intervention modessuch as the pharmacological, the behavioral, the cognitive, and the analyticwithin an overarching ontological or experiential context.

This article is an update and adaptation of my chapter entitled Existential processes. In L. Greenberg, J. Watson, & G. Lietaer (Eds.), Handbook of experiential psychotherapy (pp. 103120). New York: Guilford. K. J. Schneider ( ) 1738 Union Street, San Francisco, CA 94123 e-mail: kschneider@california.com

The reason for my focus on the experiential, as opposed to other modes within the EI framework, is twofold: rst, fewer therapists are exposed to experiential liberation principles, and therefore could benet from an in-depth elucidation, and second, experiential liberation is the culminating level of healing for many, if not most, moderate to long-term therapy clients. (For those readers desiring to know more about the full EI model, see Schneider & May, 1995, pp. 135322; Schneider, 2006, 2007). Depending on a clients desire and capacity for change, the EI therapist makes available an experiential level of contact (also termed experiential liberation). Experiential liberation embraces four overlapping and intertwining dimensions (1) the immediate, (2) the kinesthetic, (3) the affective, and (4) the profound or cosmic. These dimensions form the ground or horizon, within which each of the aforementioned intervention modes operate, and they are the context for at least one more clinically signicant set of structures. These are, according to phenomenological research, the capacities to constrict, expand, and center ones energies and experiences (Schneider & May, 1995, p. 139). Expansion is the perception of bursting forth and extending psychophysiologically. Expansion is associated with a sense of gaining, enlarging, dispersing, ascending, lling, accelerating, or in short, increasing psychophysiological possibilities. Constriction is the perception of drawing back and conning thoughts, feelings and sensations. Constriction is signied by the perception of retreating, diminishing, isolating, falling, emptying, slowing, or in short reducing psychophysiological possibilities. At their extremes, expansion and constriction form two nightmares, as Tillich (1952, pp. 6263) put it, that associate with psychological disturbance. Extreme (or hyperexpansive) fears, for example, associate with uncontrollability, disarray, and ultimately chaos; whereas extreme (or hyperconstictive) fears associate

Springer

34

J Contemp Psychother (2007) 37:3339

with entrapment, minimization, and ultimately obliteration (or the fear of being wiped away.). These two fears hyperexpansion and hyperconstrictionimpact many, if not all, of the classic psychological disturbances. For example, depression, anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder can all be characterized as hyperconstrictive overcompensations for the terror of expanding (e.g., venturing out, risk-taking). Hypomania, impulse disorders, and narcissism, on the other hand, can all be viewed as hyperexpansive overcompensations for terrors of constriction (entrapment, devaluation, belittlement). While psychiatric syndromes are sometimes relatively unipolar, more often than not, they entail complex mixtures of hyperexpansive and hyperconstrictive reactivityand these mixtures are not just endemic to, for example, bipolar disorder but the disorders mentioned above as wellalbeit in less pronounced degree. The capacity to center is the ability to be aware of and direct ones constrictive and expansive possibilities. The more one is able to centerthat is, be present to, have choice regardingones constrictive or expansive energies, the more one is able to maximize experiential liberation. The more polarized or compelled ones experience and behavior, on the other hand, the more one tends to become fragmented and devitalized (Schneider, 1999). Taken as a whole, experiential liberation is the culminating phase of a full existential-integrative course of therapy. Experiential liberation embraces not only (constrictive and expansive) physiology, environmental conditioning, cognition, psychosexuality, and interpersonal relations but also the whole network of relations to the degree possibleincluding that relating to being itself. Experiential liberation is intersituational in that it pertains, not just to this or that content or period of ones life, but to the preverbal/kinesthetic awarenesses that underlie contents and periods of ones life. As a nal note, the EI model is a relatively new development on the professional scene. To place it in the context of other therapeutic theories and practices, see the discussions of Greenberg, Watson, & Lietaer (1998); Cummings & Cummings (2000); Schneider (1990/1999); Watson & Bohart (2002); and Cooper (2003). The healing conditions of experiential liberation The aim of experiential liberation is to optimize constrictive/expansive choice. Choice at this level is characterized by immediate, kinesthetic, affective, and profound (or spiritual) dimensions of oneself. It is further characterized by vigor, creativity, and purpose. There are four therapeutic subconditions or stances that promote experiential liberation. They are: presence, invoking the actual, vivifying and confronting resistance, and cultivation of meaning and awe. Depending on clients readiness and capacity for change, these stances may be sequential (as

Springer

ordered above) or they may be in varying order. Generally they follow the aforementioned pattern. Presence Presence is the sine qua non of experiential liberation. It is the beginning and the end of the approach, and it is implicated in every one of its aspects. Presence serves three basic therapeutic functions: it holds or contains the therapeutic interaction; it illuminates or apprehends the salient features of that interaction; and it inspires presence in those who receive or are touched by it. Presence is palpable. It is a potent sign that one is here for another. In the classic drama Divine Comedy, the spiritguide Virgil exhibits the abiding quality of presence when he conveys to his charge, Dante: I will be with you, as long as I can be of help to you (Schneider & May, 1995, p. 25). Being with another, clearing a space for another, and fully permitting another to be with and clear a space for him or herself are all earmarks of presence (see Hycner & Jacobs, 1995). Another way to dene presence is by its absence. When a therapist is distracted, when she is occupied by matters other than the person sitting before her, there is a distinct weakening of the relational eld. From the standpoint of the client, the eld feels porous, uninviting, precarious, cold, and remote. However, when a therapist is fully present, the relational eld alters radically. Suddenly, there is life in the setting. The therapist acquires a vibrant, embracing quality. The therapeutic eld becomes a sanctuary, to use Erik Craigs (1986) ne term, and the client has a sense of being met, held, heard, and seen. These qualities, in turn, invite the client to feel met, held, heard, and seen within himself. It is in this sense that even before a word is exchanged, the therapist becomes a mirror for the client, and helps that client to disarm. Presence also illuminates a clients (and therapists) world. This illumination is closely connected to empathy, but not to diagnostic assessment (Greenberg, Rice, & Elliott, 1993; Bohart, 1991). The therapist becomes a barometer, not just for what is happening in the client, but for what is happening in the eld between her and the client (Friedman, 1995). Put another way, presence illuminates the entire atmosphere of therapist-client interaction. It is reected in the (silent) question, What is really going on here? What is palpable? and Where is the charge in this relationship? It is through this prism of inquiry that a deep and holistic gestalt begins to emerge about a given relationship. The therapist begins to sense, not merely what the client is saying, but how the client is being, while hes saying it. Presence reveals much more about clients than can be accessed by standardized assessments. It allows for surprise, self-correction, and moment to moment unfolding. But it

J Contemp Psychother (2007) 37:3339

35

also, signicantly, allows for a rich and panoramic understanding of the therapeutic encounter. The moment I meet with someone, I immediately attune to how we are together. What is the taste, feel, and texture of our contact? How do we sit with one another, position ourselves, and make eye contact? How does this person before me sit, move, and gesture? Is he in my face, or is he soft, pliable? Is he effusive, or is he subdued? Does he quiver, or is he composed? How does he dress? What vocal uctuations does he display? What is his energy level and where do I feel pulled in this relationship? All of these questions are clues for me, microcosms of a dynamic, evolving picture, and portents of challenges to come. The presence of the therapist to his or her own fears and anxieties serves as a model to clients. To the degree that therapists can tolerate and accept a wide variety of experiences within themselves, clients too are inspired to acquire such abilities. As a result, therefore, clients are able to deepen as therapy proceeds, to become more accessible, expressive, and intentional (Bugental, 1987; May, 1969); which is very different, typically, from that which clients derive by pharmacological means, behavioral or cognitive reprogramming, or intellectual explanation. In sum, presence holds and illuminates that which is palpably (immediately, kinesthetically, affectively, and profoundly) relevant within the client and between the client and therapist. Presence is both the ground and eventual goal of experiential work.

Invoking the actual Invoking the actual invites and encourages clients into that which is palpably (immediately, kinesthetically, affectively, and profoundly) relevant. If presence holds a silent mirror to clients depths, invoking the actual holds a more active and vocal mirror to those depths. Borrowed from Wilson Van Dusen (1965), invoking the actual calls attention to clients ways of speaking, gesturing, feeling, and sensing. It is an attempt to alert clients to what is alive and charged in the relationship. The leading question of invoking the actual is, What is really going on here (within the client and between myself and the client) and how can I assist the client into what is really going on? That which is frequently going on cuts beneath the clients (or therapists) words and discursive content. The therapists job is to be attuned to these processes and,as appropriate, call clients attention to them. This calling of attention helps clients to experience the expansive rage, for example, beneath their constrictive sadness, or the contractive melancholy beneath their expansive bravado. Or it helps clients experience their polarizations in relation to the therapist and the therapists responses to them.

Some of the verbal invitations to invoke the actual include topical focus, topical expansion, and noting content/process discrepancies. Topical focus is usually at the beginning of given sessions and includes such comments as these: Take a moment to see whats present for you? What really matters right now? and Can you give me an example? The focus on personal experience, moreover, is also a salient entree into the actual. Encouraging clients to make I statements and to speak in the present tense illustrate this focus. Topical expansion helps clients to elaborate on and deepen their experiences. Prompts like, Tell me more, Stay with that (feeling) a few moments, or You look like you have more to say, all can facilitate further immersion in ones concern (Bugental, 1987). Content/process discrepancies are notable differences between what a client says and how she says it. Examples include: You say you are ne, but your face is downcast, or Your body hunches over as you talk about your girlfriendI wonder what thats about, or When you talk about that job, your eyes seem to moisten. Inviting clients to be with their most intimate expressions requires great sensitivity. The therapist must be attuned, not only to process issues but to clients abilities to encounter those issues. I always make an effort to check in with clients who seem to be struggling with these intimate awarenesses. I might inquire, for example, how this style of approach is going for them, or suggest that they can signal me if our encounters become too intense. There is always room for exibility with invoking the actual, and for clients to take charge of the format. Of course, there are times where I will reect back to clients their need to shift out of our intensive process, but I genuinely try to gauge the usefulness of such feedback and to be as empathic as possible when I provide it. One of the great values of invoking the actual is the wealth of information that it provides, even when clients decline to engage it. Raising clients consciousness about their feelings, bodies, styles of existing, at the very minimum plants seeds for clients, helps them to see where they may want to continue the invocation at some future date, and may well even jar clients into presently re-engaging their intensive contact. When I invited my client Emma to vent her animus toward her uncle in a role play, she was not intially able to do so. However, she learned a great deal about herself from that invitation and in a subsequent role play, exploded at her uncle. Invoking the actual can be understood in terms of a spectrum of intensity. I view the invocations I described above as orienting invocations. They spur clients to be present to their sufferings, but they frequently require supplemental offerings to deepen and consolidate that which has been achieved. In this regard, I have found silence, gentle prompts to hang in with the pain, guided or embodied meditation, and interpersonal encounter to be vital. Before delving into these

Springer

36

J Contemp Psychother (2007) 37:3339

areas, however, there is one key area of invoking the actual that has yet to be addressedtrust. One recent evening, a jittery supervisee stepped into my ofce. He was deeply intrigued by the experiential concepts we had been exploring but had one overarching question: What do you do after the client is immersed? The panic exhibited by this student is not uncommon among beginning trainees (not to mention seasoned veterans at times!). To sit with clients in pain, to have no idea where that pain will lead, or whether it will dissipate, is unsettling indeed. The cultivation of trust, however, is one of the primary experiential tasks. Without trust, no therapist could have the steadiness, patience, supportiveness, and stark belief in the healing powers of the client that experiential work demands. Among trusting experiential therapists, there is a refusal to equate clients with their dysfunctions. Further, such therapists are continually open to the more (or awe) of consciousness, the more (or awe) of living. From this standpoint a client is more than a depressive, but a dynamic, unfolding person. My advice to the supervisee?do not withdraw from the situation too hastily. Gently suggest to the client to stay present, that more may emerge, and that, come what may, you are here for your client. In my experience, too many trainees (and professionals) do not heed this advice and rob the client of three illuminating scenarios: the experience of deepening, the experience of an inability to deepen, and the experience of resistance to deepening. Guided (or embodied) meditation is one of the most transformative forms of invoking the actual of which I am aware (see Schneider & May, 1995 for a full explication of this modality). Guided meditation, as I conceive it, entails concerted invitations to clients to enter embodied, meditative states. I try to be exible about how I structure guided meditation. Sometimes I suggest a sequence of simple breathing exercises, attunement to and identication of a somatic tension area, and invitations to physically self-contact the identied tension area. I follow up this sequence with an invitation to clients to associate to the feelings, fantasies, and images aroused by the tension area. At other times, I directly invite clients to attune to bodily tension areas and to free associate to these areas. At still other times, I invite clients to soley make physical (e.g., hand) contact with their anxiety and experience what emerges. In short, I cannot overestimate the impact of this style of experiential immersion for certain clientsit cuts through to the core. The eld that occurs between client and therapist is another salient opening for invoking the actual. The interpersonal encounter, as I (and other existential theorists) call it, possesses three basic dimensions: the real or present relationship between therapist and client; the future and what can happen in the relationship (versus strictly the past and what has happened in relationships); and the acting out or experiencing to the degree appropriate, of relational mateSpringer

rial (Schneider & May, 1995, p. 165). The encounter enables clients to open up their deepest fears and fantasies directly, in the living relationship. The encounter enables clients to work through those fears and fantasies in an intensive but safe relationship. Finally, the experiential dimension of the encounter can be enhanced and deepened through timely invitations to stay present to the feelings, sensations, and images brought up by the encounter (see Schneider & May, 1995 and Hycner & Jacobs, 1995 for an elaboration on each of these points). While there are many other ways to invite and encourage clients into the palpably relevant (see Schneider & May, 1995 for a fuller discussion), the challenge is to cultivate them, tailor them to the situation, and creatively rene them.

Consider the following vignette as an illustration My client James1 is sitting across from me hurriedly reporting on the difculties he had over the past week. I take a full breath and center myself: James, I interject, I wonder if you can take a moment and check in with what youre feeling right now, as you talk about that put-down last week. A little taken aback, James suddenly pauses a moment. He looks inward, and he inhales: Im pissed! he exclaims. Ive had a weekno, a lifetimeof being treated like shit, I turn to a person I thought was a close friend, and even she, apparently, cant stand the sight of me, and I just dont get itdont know where to turn. [Now James is connecting with himself; hes slowed down enough to be authentically present to his anger, here and now. His life is not just a string of complaints; it has some passion, aliveness, and I decide to highlight that passion and aliveness.] Me: Boy, you have a lot of energy all of a sudden, James. James: Yeah, I do, he retortsbut what the hell good is it? I can get mad from now until doomsday, and it wont change the fact that women think Im pervert, men think Im a weakling, and my boss thinks Im incompetent! Me: And what do you think of you? What do you feel toward you? James: I feel like a jerkwhat do you think!? Me: I dont know, James, I cant speak for you, but I hear you.(James slouches in his chair as if to fold up in total resignation.) Me: Where are you now, James? James: [eyes moistening] Im stuck, Im screwed. . . Me: Looks like some emotion is welling up. James: Yeah, sometimes I feel like my life is a big wall and Im the bug that constantly gets squashed. Me: Is that where you are now? James: Not exactly.

1

James is a ctional composite of a typical client from my practice.

J Contemp Psychother (2007) 37:3339

37

Me: Take a moment and be with where you are James. James: Im hurtin. Me: Can you describe where you feel that hurt, James? James: Yeah, its in my chestall clogged up. Me: See if you can stay with that feeling in your chest, what other feelings, sensations, or images come up for you as you stay with that feeling? Summary: This vignette illustrates how invoking the actual has helped James move from a distant reporter to an embodied participant. Gradually, as James experiences more and more of himselfe.g., his affect and body sensationsmore and more of himself can be accessed and expressed. Put another way, James is discovering how to be with himself. Through this intensied awareness, he is experiencing both what is emerging within himself, and also, as we shall see next, how he blocks himself from that emergence. The combination of the two is what will mobilize choice.

Vivifying and confronting resistance (or protections) When the invitation to explore, immerse, and encounter are abruptly or repeatedly declined by clients, then the delicate problem of resistance (or client self-protection) must be considered. Resistances are blockages to that which is palpably relevant. There are several caveats to bear in mind about experiential work with resistances. First, therapists can be mistaken about resistances. What I label resistance, for example, may simply be the refusal on the part of the client to follow my agenda. It may also be a safety issue for the client or an issue of cultural or psychological misunderstanding. It is of utmost importance therefore, to bracket our attributions of resistance, and to clarify their pertinent roots. Second, it is crucial to respect resistances. Resistances (or what I have increasingly come to term, protections) are lifelines to clients and as miserable as clients patterns are, they are the scaffoldings of their existence, both known and familiar. Resistances, moreover, demarcate the monumental battle that clients experience. As previously indicated, this battle consists of two rivaling factionsthe side of the client that struggles to emerge and the side that struggles to suppress that emergence, that remains entrenched. It is crucial, in my view, to name this battle with clients, which is the most important of their lives. Resistance work is mirroring work. Whereas invoking the actual mirrors clients struggles to express and access themselves, resistance work, as previously noted, mirrors clients barriers to that freedom. Resistance work must be artfully engaged. The more that therapists invest in changing clients, the less they enable clients to struggle with change. By contrast, the more that therapists help clients to clarify how they

are willing to live, the more they fuel clients impetus (and often frustration!) required for lasting change. Vivifying resistance is the amplication of clients awareness of how they block themselves. Specically, vivication serves three therapeutic functions: (1) It alerts clients to their defensive worlds; (2) apprises them of the consequences of those worlds; and (3) reects back the counterforces aimed at overcoming those worlds. There are two basic approaches associated with vivifying resistancenoting and tagging. Noting acquaints clients with initial experiences of resistance. Some examples of noting are: Your voice gets soft when you speak about sex; You were sad, and suddenly you switched topics; It is difcult for you to look at me when you express anger. Tagging alerts clients to the repetition of their resistances. Some examples are: Whenever we discuss this topic you draw a blank; Everytime you explore your career goals you look resigned; You repeatedly appear to want to blame others for your misery. In addition to noting and tagging, there are also a variety of other verbal and nonverbal vivications of resistance (See Schneider & May, 1995, pp. 168170). It is even sometimes helpful to simply support clients resistance; particularly when such clients are immovable. This support alleviates the pressure on clients to self-disclose and can, paradoxically, accelerate renewed self-disclosures (see Schneider, 1990, pp. 194 198). In exceptional circumstances clients need more than a mere acknowledgment of their defensive patterns; they need a confrontation with those patterns. Whereas vivifying resistance alerts clients to their polarized stances, confrontation alarms them about those stances. While confrontation has its benets, usually toward the latter stages of therapy, it is imperative that therapists be selective about it. If confrontation is too intense, the therapist may rob the client of responsibility for facing a life decision; or, correspondingly, he may lose the client altogether. Perceived correctly, confrontation is an amplied form of vivication. It still informs clients about how they delimit their worlds, but it does so dramatically, with foundation-shaking signicance. Although there are no clear-cut criteria for confronting, three elements are generally present: chronic client entrenchment (or polarization), a detectable (if faint) sense of ght in the client; and a strong therapeutic alliance. Here are some examples of confronting: You say you cant confront your wife but you mean you wont! How many times are you going to keep debasing yourself with men? Youd rather argue with me than get on with your life! If youre not going to blast your abusive boss, then I will! There are, of course, times to acknowledge the fatigue, torment, and basic helplessness that clients feel before their resistances. This is especially true as clients approach liberation, which can be the most resistant period of all. Such

Springer

38

J Contemp Psychother (2007) 37:3339

acknowledgments provide perspective and the room for clients to regroup. A useful rule of thumb for therapists confronting or even vivifying client resistance is to practice what I call, following Taoist philosophy, effortful nonattachment. Effortful nonattachment invites and even amplies an available state of change, but without the therapists overidentication with a particular transformative outcome. This active yet suspenseful stance leaves the responsibility for change squarely on the shoulders of the client. I continue our vignette with James to illustrate vivifying and confronting resistance. In this excerpt, we nd James becoming chronically identied with his lowly position in society. He is terse, dgety, and intransigentbut with a hint of budding deance. James: Diana called me the other day. She was the one friend I had some decent contact withuntil I went and stuck my foot in my mouth. She asked me to see a movie with her and I made a stupid remark about seeing a porno ick to jazz up our evening together. She then told me abruptly that she was offended by my suggestion, and that further, she was no longer in the mood to go out that night. How could I have done that?! How could I have taken a perfectly decent relationship, a relationship I knew wouldnt go anywhere romantically, and push it off the cliff? Theres just no way around it, Im doomed to be a shit. Me: Is that all you are, James, is that what your whole life and all youve been through comes down to? James: Seems so. Me: Yeah, you seem insistent on thatyouve seemed insistent on that for weeks. Is that acceptable to you? James: No, but theres nothing I can do about it. Me: What are you willing to do about it? James: Weve been around that bend before. Me: Yes, we have James, are you willing to go around it in the same way you have before?[James pauses, he looks down. Its the rst time in this sequence that hes slowed down enough to reassess himself.] James: Well, I am sick and tired of it. Me: I hear you. What else is here, James? James: That maybe I wasnt as much the shit as I made myself out to bethat I always make myself out to be. That I slipped upI made a stupid comment, am I gonna condemn myself for life? Me: Stay with it, James, what else is present for you? James: A hint of pride, deance. Me: Say more. Such sequences and revisitations of old stuck places are hallmarks of vivifying and confronting resistance. In the sequence above, James is able to move from a tiring and familiar self-loathing, to a realization of the narrowness of that loathing, and the possibility for something more, some

kind of pride or deance in his life. Those are attributes that we can build on, and do build on, as the therapy proceeds.

Meaning-Creation and the Cultivation of Awe As clients face and overcome the blocks to that which brings them alive, they begin to discern the meaning (e.g., future implications) of their odysseys. Concomitantly, they also begin to discover the humility and wonder, thrill and anxiety, or in short, awe, of a fully engaged consciousness (Schneider, 2004). These changes are not abstract or intellectualized but embodied. They are the result of a hard-won encounter with who one will be in spite of and in light of all that one has discovered about oneself. This greater accessibility yields new shapes, textures, and priorities to clients lives. Whereas formerly a given client may have hidden himself or herself in the world, now he or she is capable of declaring herself in the world; and whereas other clients may have restricted themselves intellectually, physically, or emotionally, now they are able to nd meaning in scholastic or athletic pursuits, religiosity, or romance. The key here is not the contents of those discoveries per se, but what clients bring to those contentse.g., passion, creativity, and imagination. Whereas before clients were precluded from those avenues of motivation, now they are able to occupy them, range within them, and implement them in their lives. It is not that all symptoms or problems are eradicated through such a process, it is simply that the major barriers to choice in a given area (or areas) are removed. The result for such clients is that they are able to live more spaciouslymore paradoxicallyand to respond to rather than react against lifes evolving challenges. Returning to my work with James, a few excerpts from our nal session will serve to illustrate: James: The grocer gave me a snippy look again today. Me: So, where did that leave you? Correction, where does that leave you? James: Well it leaves me in a very different place than it would have a few years ago. Back then, I wouldve buried myself in shame and self-loathing. Today I moved on. It made me realize how far Ive come since those dark daysafter that grocer gave me that look, I got pissed, momentarily, but then I took a breath, carried my bags outside, and noticed the air outside. It was crisp and cool. I took a breath and I felt a big refreshing clearing inside that profoundly reected the freshness and brightness of the outdoors. And then I remembered how much I had going in my lifethe budding friendship with Al, the new focus on my computer studies, my relationship with Sonny [Jamess dog], and the fact that I was alive, OK with the life Ive built. So thats how I feel now, its not all sweetness and light, for sure, but I dont feel so trapped anymore, so driven. And that has afforded me the

Springer

J Contemp Psychother (2007) 37:3339

39 Hycner, R., & Jacobs, L. (1995). The healing relationship in gestalt therapy: A dialogic/self psychology approach. Highland. NY: Gestalt Journal Press. May, R. (Speaker). (1987). The Relevance of Existential Therapy to Todays World. [To be available on DVD from www.psychotherapy. net in 2007]. May, R. (1969). Love and Will. New York: Norton. Schneider, K. (1990/1999). The paradoxical self: Toward an understanding of our contradictory nature (2nd. ed). Amityville, NY: Humanity Books (an imprint of Prometheus Books). Schneider, K., & May, R. (1995). The psychology of existence: An integrative, clinical perspective. New York: McGraw-Hill. Schneider, K. (1998). Existential processes. In L. Greenberg, J. Watson, & G. Lietaer. (Eds.), Handbook of experiential psychotherapy (pp. 103120). New York: Guilford. Schneider, K. (2003). Existential-humanistic psychotherapies. In A. Gurman & S. Messer. (Eds.), Essential psychotherapies (pp. 149 181). New York: Guilford. Schneider, K. (2004). Rediscovery of awe: Splendor, mystery, and the uid center of life. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House. Schneider, K. (2006). American Psychological Association (Producer). Existential Therapy [Video in the Systems of Psychotherapy Series]. Available online at www.apa.org/videos from the American Psychological Association, 750 First Street, Washington, DC 20002-4242. Schneider. K. (2007). Existential-integrative psychotherapy: Guideposts to the core of practice. New York: Routledge. Van Dusen, W. (1965). Invoking the actual in psychotherapy. Journal of Individual Psychology, 21, 6676.

chance to get on with what really counts in my lifeto live it. A more eloquent summation for experiential liberation could scarcely be wrought. James, echoing the words of Rollo May (1987), implies that its not this or that symptom, but ones life that is at stakeand that this is what therapists of all stripes need to see. References

Bohart, A. (1991). Empathy in client-centered therapy: A contrast with psychoanalysis and self-psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 31(1), 3448. Bugental, J. (1987). The art of the psychotherapist. New York: Norton. Cooper, M. (2003). Existential Therapies. London: Sage. Cummings, N., & Cummings, J. (2000). The essence of psychotherapy. New York: Academic Press. Craig, E. (1986). Sanctuary and presence: An existential view of the therapists contribution. The Humanistic Psychologist, 14(1), 22 28. Friedman, M. (1995). Dialogical (Buberian) therapy: The case of Dawn. In K. Schneider & R. May (Eds.), The psychology of existence: An integrative, clinical perspective (pp. 308315). New York: McGraw-Hill. Greenberg, L., Rice, L., & Elliott, R. (1993). Facilitating emotional change: The moment by moment process. New York: Guilford. Greenberg, L., Watson, J., & Lietaer, G. (Eds.) (1998). Handbook of experiential psychotherapy (pp. 328; 103120). New York: Guilford.

Springer

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Thematic Guide To Young Adult LiteratureDocument269 paginiThematic Guide To Young Adult LiteratureJ S ShineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edward T. Hall - Beyond Culture-Doubleday (1976)Document384 paginiEdward T. Hall - Beyond Culture-Doubleday (1976)Tristan ZarateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liminal DebrisDocument1 paginăLiminal Debrisoana liminalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Year SieveDocument1 paginăNew Year Sieveoana liminalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Key Ideas For Avoiding Freedom and ResponsibilityDocument13 paginiKey Ideas For Avoiding Freedom and Responsibilityoana liminalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Attachment Research Relevant To Working ModelsDocument2 paginiAttachment Research Relevant To Working Modelsoana liminalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Core Assumptions in Existential PsychotherapyDocument1 paginăCore Assumptions in Existential Psychotherapyoana liminalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thee Only Language Is LightDocument10 paginiThee Only Language Is Lightoana liminalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive DistortionsDocument7 paginiCognitive Distortionsoana liminala100% (1)

- SESS BEHAVIOUR RESOURCE BANK Advice Sheet 22 Individual Behaviour Support PlanDocument8 paginiSESS BEHAVIOUR RESOURCE BANK Advice Sheet 22 Individual Behaviour Support Planstudysk1llsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Because of Winn Dixiech1and2Document22 paginiBecause of Winn Dixiech1and2MONICA LUM100% (1)

- Hospice Care PaperDocument12 paginiHospice Care Paperapi-247160803100% (2)

- Descriptive Essay Introduction ExamplesDocument5 paginiDescriptive Essay Introduction ExampleszobvbccafÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volleyball ManualDocument214 paginiVolleyball ManualmrsfootballÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee Performance Impact of Teamwork, Empowerment & TrainingDocument15 paginiEmployee Performance Impact of Teamwork, Empowerment & TrainingAbdul HadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emotions and how to communicate feelingsDocument8 paginiEmotions and how to communicate feelingsnurulwaznahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protection of Children: A Framework For TheDocument36 paginiProtection of Children: A Framework For TheLaine MarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- GHWA-a Universal Truth Report PDFDocument104 paginiGHWA-a Universal Truth Report PDFThancho LinnÎncă nu există evaluări

- SampsonDocument9 paginiSampsonLemon BarfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daily Lesson LOG: Eastern Cabu National High School 11Document3 paginiDaily Lesson LOG: Eastern Cabu National High School 11Mariel San Pedro100% (1)

- Character Profile FormDocument16 paginiCharacter Profile FormPlot BUnnies100% (1)

- Book Review The Leader Who Had No Title PDFDocument7 paginiBook Review The Leader Who Had No Title PDFJamilahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minggu 2: Falsafah Nilai & EtikaDocument12 paginiMinggu 2: Falsafah Nilai & EtikaNur Hana SyamsulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Level of Learning Motivation of The Grade 12 Senior High School in Labayug National High SchoolDocument10 paginiLevel of Learning Motivation of The Grade 12 Senior High School in Labayug National High SchoolMc Gregor TorioÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study On Effectiveness of Conflict Management in Apollo TyresDocument27 paginiA Study On Effectiveness of Conflict Management in Apollo TyresRanjusha AntonyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Holding Police AccountableDocument38 paginiHolding Police AccountableMelindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample TechniquesDocument3 paginiSample TechniquesAtif MemonÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSY285 Assign 2 Lin Y34724878Document10 paginiPSY285 Assign 2 Lin Y34724878Hanson LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01797johari WindowDocument23 pagini01797johari WindowAjay Kumar ChoudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Must We Study The Question of Indolence Among The FilipinosDocument2 paginiWhy Must We Study The Question of Indolence Among The FilipinosRoma Bianca Tan Bisda100% (6)

- Year 12 Re Self-Assessment RubricDocument2 paginiYear 12 Re Self-Assessment Rubricapi-253018194Încă nu există evaluări

- 2J Coordination: Time: 1 Hour 5 Minutes Total Marks Available: 65 Total Marks AchievedDocument26 pagini2J Coordination: Time: 1 Hour 5 Minutes Total Marks Available: 65 Total Marks AchievedRabia RafiqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cornelissen (5683823) ThesisDocument48 paginiCornelissen (5683823) ThesisAbbey Joy CollanoÎncă nu există evaluări

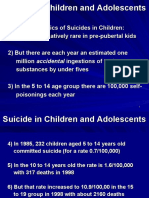

- Suicide in Children and Adolescents: AccidentalDocument32 paginiSuicide in Children and Adolescents: AccidentalThambi RaaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conflict ResolutionDocument2 paginiConflict ResolutionmdkaifahmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching English For Young Learners: Mid AssignmentDocument4 paginiTeaching English For Young Learners: Mid AssignmentAbdurrahman NurdinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Budgeting: Advantages & LimitationsDocument8 paginiBudgeting: Advantages & LimitationsSrinivas R. KhodeÎncă nu există evaluări