Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

A Critical Review of SLT

Încărcat de

tomorDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Critical Review of SLT

Încărcat de

tomorDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP THEORY

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP THEORY Situational Leadership Theory is arguably the most widely known and practiced theory of leadership and managerial effectiveness. In this essay, the origins and fundamentals of the theory are considered, as well as the available evidence that supports or contradicts the its validity. Background Situational Leadership Theory as presented by Hersey and Blanchard developed from the work of J. W. Reddins 3-Dimensional Management Style Theory. That theory hypothesizes the importance of a managers relationship orientation and task orientation in conjunction with effectiveness (Reddin 1967, 8). From the interplay of these dimensions, Reddin proposes a variety of management styles and theorizes that effectiveness as a manager can be explained as a function of matching a leaders style to a specific situation. However, his theory does not specify whether certain situational characteristics could be unequivocally incorporated into a predictive model (Vecchio 1987, 444). From Reddins suggestion that a leaders effectiveness varies according to style, Hersey and Blanchard proposed a life-cycle theory of leadership. According to this theory, degrees of task orientation and relationship orientation are to be examined in conjunction with the maturity of a follower or group of followers in order to account for leader effectiveness (Hersey and Blanchard 1969, 29). The main principle of the life-cycle theory is that as the level

2 of maturity in a follower increases, effective leader behavior will involve less task orientation as

3 well as less relationship orientation. However, this decline in both orientations is not straightforward. Hersey and Blanchard theorize that a low level of relationship orientation coupled with a high task orientation is ideal in the early stages of an employees tenure under leadership. As the employees maturity increases, the need for the leader to provide relational support increases while the need for task orientation declines. At the highest level of employee maturity, task and relationship orientation become superfluous to employee effectiveness (Hersey and Blanchard 1969, 29). Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson provide even greater precision to their theory in a text now in its eighth edition. In Management of Organizational Behavior: Leading Human Resources, the authors state that follower maturity can be separated into categories of high, moderate and low, and that the appropriate style of a leader can be summarized with the categories of telling, selling, participating or delegating in their relationships with employees (Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson 2001, 173-174). It is this most recent model that is considered below. Fundamentals The basic premise of Situational Leadership Theory is that there is no single superior way to influence another individual or group. Rather, the leadership style a person should use is dependent upon the degree to which an individual or group is ready to be influenced. The theory suggests four different leadership styles derived from the varying ways in which task behavior (the extent to which a leader engages in giving out work responsibilities) and relationship behavior (the degree to which a leader engages in communication with employees) intersect. The first leadership style is characterized by large amounts of task behavior and low amounts of relationship behavior. Style two is characterized by high levels of both task and relationship

4 behavior. Style three is characterized by high levels of relationship behavior and low levels of task behavior. The fourth leadership style is characterized by low amounts of both task and relationship behavior (Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson 2001, 174). Readiness in Situational Leadership Theory is defined as the degree to which a follower demonstrates the ability (those gifts or tools one brings) and willingness (the degree to which one is motivated) to complete a given task. The degree to which ability and willingness relate to one another determines the degree of readiness an individual or group has. The authors developed a continuum of readiness to explain the various ways in which willingness and ability interact. At level one, a follower essentially lacks the skill and desire to complete a given task. At level two, an employee is either unable but willing or confident. At level three, an individual is able to complete a task, but is unwilling or insecure. At level four, one is able, willing and confident (Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson 2001, 177-178). Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson created a model to help make the Situational Leadership Theory practical. As followers move from right to left on the development level continuum at the bottom of the model, the combinations of task and relationship behavior (that is, the leadership style) appropriate for a given situation begin to change. By identifying a point on that continuum that represents the degree to which a follower has developed and constructing a perpendicular line from that point to the place where it intersects with the bell curve in the leadership style model, one can get a relatively accurate idea about the most appropriate leadership style necessary for a given situation (Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson 2001, 181). Primarily, a level one readiness factor correlates with a style one leadership style, a level two readiness factor correlates with a style two leadership, and so on.

6 Theoretical Analysis Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson have found that Situational Leadership Theory has meaningful application in every kind of organizational setting, and that the concepts apply in any situation in which people are trying to influence the behavior of other people (Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson 2001, 197). By simply adapting some of the language of the theory to fit the appropriate circumstances, the authors boast wide application and success. The theory can help parents determine the appropriate parenting style, or help teachers better relate to individual students (Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson 2001, 198199). In any situation where there is an attempt to influence behavior, Situational Leadership Theory can be a helpful tool. Though widely known and used, Situational Leadership Theory may not have the final word on leadership and management. There are substantive questions raised in the literature regarding the theorys validity. Vecchio questions whether Situational Leadership Theory is a synthesis of a myriad of other insights from a variety of other theories. He points out that with this possible synthesis, one could argue that Hersey and his colleagues are not offering anything new or original with their theory. Nevertheless, one might also contend that Situational Leadership Theory is superior in that it focuses on critical features of behavior that have been previously identified (Vecchio 1987, 444-445). Claude Graeff gives a comprehensive critical review of the theory that attempts to discredit it at both the theoretical and pragmatic level. He first argues that the theory may have derived from a 1966 article by A. K. Korman who suggested the probability of a curvilinear relationship between dimensions of leader behavior and other variables (Graeff 1983, 285). Additionally, Graeff argues that presenting a four-dimensional model (task orientation,

7 relationship orientation, follower maturity, and effectiveness) in a two-dimensional graphic is a critical problem for the theory. This conceptual contradiction is partially illustrated by the fact that at readiness levels one and three, workers are said to be unwilling or unmotivated, while at readiness levels two and four, workers are said to be motivated. Graeff points out that these assertions are inconsistent with the linear (scale) exhibited in the model (Graeff 1983, 286). In the same critique, Graeff also points out the theorys tendency to overemphasize the ability dimension, and how this overemphasis can severely limit the usefulness of the theory (Graeff 1983, 287). If an employee has a low self-esteem that results in a low level of selfconfidence, his willingness will be virtually non-existent and his performance will be poor. According to the theory, this low level of maturity calls for high task, low relationship leadership that has coercion as its base. Yet the theorys authors do not advocate coercion for employees that are insecure or shy (Hersey, Blanchard and Johnson 2001, 210-214). It is reasonable to anticipate the need for high relationship in such a situation, yet the model suggests the opposite. Empirical Analysis Blanchard and colleagues report that over 50 dissertations, masters theses and research papers have been written using the improved LBA and LBA II (instruments associated with the theory) since 1983 (Blanchard, Zigami and Nelson 1993, 28). A review of the literature, however, supports many others who have concluded that published empirical analysis of Situational Leadership Theory has been rare and relatively conflicting regarding its accuracy. Hambleton and Gumperts 1982 study asked managers to randomly choose four subordinate employees to complete a survey instrument. Manager ratings of subordinate maturity were coded in conjunction with manager self-assessments of leadership style. The researchers identified matches and mismatches with this coding, with only 29% of the cases matching

8 (Hambleton and Gumpert 1982, 225-242). Vecchio points out that while these findings show some empirical support for the theory, a myriad of concerns regarding the structure and process of the study all but disqualify any support the study might give (Vecchio 1987, 445). In a study published in 1990, Blank, Weitzel and Green issued the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire to 27 university hall directors and a self-developed measure of maturity to 353 resident advisors. The hall directors provided performance ratings of resident advisors, and resident advisors completed subscales of the Job Description Index satisfaction measure. The researchers analysis examined interactions between subordinate maturity and leader style behavior dimensions in an attempt to predict subordinate job satisfaction and performance. The result revealed no support for Situational Leadership Theory (Blank, Weitzel and Green 1990, 579-597). In an attempt to validate Situational Leadership Theory, Vecchio issued a variety of instruments to 303 high school teachers and 14 high school principles. Vecchio found support for the theory in the low maturity condition, inconclusive support for the theory in the two levels of moderate maturity, and no support for predictions of Situational Leadership Theory for subordinates with high maturity (Vecchio 1987, 447-450). In a 1992 study, Norris and Vecchio distributed instruments to 91 nurses and their supervisors and found similar results to the 1987 study (Norris and Vecchio 1992, 336-339). A 1997 study of 332 university employees and 32 supervisors led Fernandez and Vecchio to conclude that Situational Leadership Theory has little descriptive utility (Fernandez and Vecchio 1997, 67). Finally, Cairns and associates sought to test the central hypothesis of Situational Leadership Theory that the interaction of leader behavior and employee readiness determines leader effectiveness. One hundred and fifty-one senior level employees of a large Fortune 100

9 company were tested. While the theory suggests that the right level of task behavior and relationship behavior should match the level of readiness maturity in followers, only 12% matched, providing no support for the Situational Leadership Theory (Cairns et al. 1998, 113116). In summary, empirical evidence provides only partial support for the principles of Situational Leadership Theory, and lends credence to the criticisms presented by Graeff and others. Conclusion Hersey, Blanchard and Johnsons Situational Leadership Theory has made a significant impact in the field of leadership and organizational research. By bringing attention to the situational nature of leadership, calling for flexibility on the part of anyone in position to influence behavior and recognizing the inherent duality of leadership, the authors serve leaders and followers well. Nevertheless, the lack of empirical support is a powerful critique of an otherwise attractive and intriguing theory. Further research would be a valuable asset towards a better understanding of the theory and in explaining the sharp contrast between the lack of empirical evidence and the broad, eager acceptance the theory holds in a myriad of fields across the globe.

10

REFERENCE LIST Blanchard, K. H., D. Zigarmi and R. B. Nelson. 1993. Situational leadership after 25 years: A retrospsective. The Journal of Leadership Studies, 1 (1): 21-36. Blank, W., J. R. Weitzel and S. G. Green. 1990. A test of the situational leadership theory. Personnel Psychology. 43 (3): 579-597. Cairns, Thomas D., John Hollenback, Robert C. Preziosi and William A. Snow. 1998. Technical note: A study of Hersey and Blanchards situational leadership theory. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 19 (2): 113-116. Fernandez, Carmen F. and Robert P. Vecchio. 1997. Situational leadership theory revisited: A test of an across-jobs perspective. Leadership Quarterly. 8 (1) (Spring): 67-74. Goodson, J. R., G. W. McGee and J. F. Cashman. 1989. Situational leadership theory: A test of leadership prescriptions. Group and Organization Studies. 14: 446-461. Graeff, Claude L. 1983. The situational leadership theory: A critical view. Academy of Management Review. 8 (2): 285-291. _________. 1997. Evolution of situational leadership theory: A critical review. Leadership Quarterly. 8 (2) (Summer): 153-170. Hambleton, R. K. and R. Gumpert. 1982. The validity of Hersey and Blanchards theory of leader effectiveness. Group and Organization Studies. 7: 225-242. Hersey, P. and K. H. Blanchard. 1969. Life cycle theory of leadership: Is there a best style of leadership? Training and Development Journal. 33 (6): 26-34. Hersey, Paul, Kenneth H. Blanchard and Dewey E. Johnson. 2001. Management of organizational behavior: Leading human resources. 8th ed. Upper Saddle, NJ: Prentice Hall. Korman, A. K. 1966. Consideration, initiating structure, and organization criteria: A review. Personnel Psychology. 19: 349-361. Norris, William R. and Robert P Vecchio. 1992. Situational leadership theory: A replication. Group and Organization Management. 17 (3): 331-342.

11 Reddin, W. J. 1968. The 3-D management style theory. Training and Development Journal. 21 (4): 39-41. Vecchio, Robert P. 1987. Situational leadership theory: An examination of a prescriptive theory. Journal of Applied Psychology. 72 (3): 444-451.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Public Service Motivation A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionDe la EverandPublic Service Motivation A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Compensation Plan A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDe la EverandOpen Compensation Plan A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- MPeskin Leadership EssayDocument8 paginiMPeskin Leadership EssayMax PeskinÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCR Session 8 - Supprting The Management of Corporate Reputation PDFDocument20 paginiMCR Session 8 - Supprting The Management of Corporate Reputation PDFbalabambaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship Format Mba HRM - LatestDocument3 paginiInternship Format Mba HRM - LatestSadia ShahzadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- QuestionnaireDocument6 paginiQuestionnaireAzra Farrah Irdayu AzmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship Report FormatDocument2 paginiInternship Report FormatSuman PoudelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Format For Reference LetterDocument2 paginiFormat For Reference LetterNiraj KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction A Correlational Analysis of A Retail OrganizationDocument172 paginiRelationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction A Correlational Analysis of A Retail OrganizationRajhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship Evaluation FormDocument3 paginiInternship Evaluation FormSharlene GoticoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team Roles QuestionnaireDocument5 paginiTeam Roles QuestionnairesreekanthsasidharanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Refrence LetterDocument1 paginăRefrence LetterihtishamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steve Jobs' Visionary Leadership and Belbin Team RolesDocument14 paginiSteve Jobs' Visionary Leadership and Belbin Team RolesalcaperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Career Planning Questionnaire PDFDocument2 paginiCareer Planning Questionnaire PDFJinky RegonayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organizational Structures Defined and ExplainedDocument6 paginiOrganizational Structures Defined and ExplainedSunny GoyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance Appraisal of Energy Industry in BangladeshDocument28 paginiPerformance Appraisal of Energy Industry in Bangladeshziko777Încă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Positivity and Transparency On Trust in Leaders and Their Perceived Effectiveness0 PDFDocument15 paginiThe Impact of Positivity and Transparency On Trust in Leaders and Their Perceived Effectiveness0 PDFneeraj00715925Încă nu există evaluări

- Sample MarketingDocument6 paginiSample MarketingGarima SaxenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MonotonyDocument12 paginiMonotonyHeavy Gunner67% (3)

- A Survey On Employees' Job SatisfactionDocument59 paginiA Survey On Employees' Job SatisfactionZubairia Khan100% (3)

- Employee Rediiness For OdDocument268 paginiEmployee Rediiness For OdsalmanhameedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Career Planning Cazse StudyDocument12 paginiCareer Planning Cazse StudymorrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship ReportDocument4 paginiInternship ReportHassanRadwanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection Chapter 10Document5 paginiReflection Chapter 10Da NoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Worklife Balance and Organizational Commitment of Generation y EmployeesDocument337 paginiWorklife Balance and Organizational Commitment of Generation y Employeeseric_darryl_lim100% (4)

- Impulse Buying of Apparel ProductsDocument17 paginiImpulse Buying of Apparel ProductsBabu George100% (2)

- 360° Performance Assessment Questionnaire: Activity LinkDocument2 pagini360° Performance Assessment Questionnaire: Activity LinkDavid SelvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work-Life Balance (Case Study)Document2 paginiWork-Life Balance (Case Study)Khairur RahimanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 2 - Critical Reflection JournalDocument16 paginiAssignment 2 - Critical Reflection Journalapi-299544727Încă nu există evaluări

- Program Effectiveness SurveyDocument32 paginiProgram Effectiveness SurveyJohan Sebastian Villamil DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Organizational Change On The Employee's Performance in The Banking Sector of PakistanDocument8 paginiThe Impact of Organizational Change On The Employee's Performance in The Banking Sector of PakistanInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Încă nu există evaluări

- Motivation in The Work PlaceDocument2 paginiMotivation in The Work PlaceAmelia Nur IswanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Leadership Style On Job Satisfaction of NGO Employee: The Mediating Role of Psychological EmpowermentDocument12 paginiInfluence of Leadership Style On Job Satisfaction of NGO Employee: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowermentrizal alghozaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating Leadership Development and Succession Planning Best PracticesDocument25 paginiIntegrating Leadership Development and Succession Planning Best PracticestalalarayaratamaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- MU0013 - HR AuditDocument32 paginiMU0013 - HR AuditNeelam AswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- MG 370 Term PaperDocument12 paginiMG 370 Term PaperDaltonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flexible Working As An Employee Recruitment and Retention Tool in The Public Sector in Bosnia and HerzegovinaDocument7 paginiFlexible Working As An Employee Recruitment and Retention Tool in The Public Sector in Bosnia and HerzegovinaKhan Khan0% (2)

- Internship GuidelinesDocument7 paginiInternship GuidelinesAjita LahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summer Internship ReportDocument35 paginiSummer Internship ReportTejpal ShekhawatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exam OBDocument5 paginiExam OBaziza barekÎncă nu există evaluări

- 360 Feedback SystemsDocument16 pagini360 Feedback SystemsSwathi NeelakantanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Influence of Workplace Environment On Workers'Document9 paginiThe Influence of Workplace Environment On Workers'ani ni musÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capital BudgetingDocument43 paginiCapital BudgetingKhan rufiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Organisational ChangeDocument8 paginiManaging Organisational ChangeMuhammad Sajid SaeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role ConflictDocument1 paginăRole Conflictvicky20008Încă nu există evaluări

- Business in World Economy AssignmentDocument4 paginiBusiness in World Economy AssignmentPoch TiongcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Before You Start HRM NotesDocument38 paginiBefore You Start HRM NotesRishabh GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appraisal FormDocument1 paginăAppraisal Formandika zidane100% (2)

- Organizational Climate (OCTAPACE) An Insight Into Its Effect On Job Satisfaction in The IT (Information Technology) SectorDocument63 paginiOrganizational Climate (OCTAPACE) An Insight Into Its Effect On Job Satisfaction in The IT (Information Technology) SectorSatinder Singh100% (1)

- Performance Management PDFDocument5 paginiPerformance Management PDFRohanÎncă nu există evaluări

- WEEK 1 (Defining Leadership)Document4 paginiWEEK 1 (Defining Leadership)Joshua OrimiyeyeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 8. Empowerment and ParticipationDocument21 paginiLesson 8. Empowerment and ParticipationElia Kim FababeirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study - HRDocument1 paginăCase Study - HRAnjali TripathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lead Work Place CommunicationDocument26 paginiLead Work Place CommunicationÑätÎnk EtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership QuestionaireDocument1 paginăLeadership QuestionaireJayapal HariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personality Test (Introduction)Document40 paginiPersonality Test (Introduction)Wilma Y. VillasanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organization Structure and Design Notes Chapter 10Document7 paginiOrganization Structure and Design Notes Chapter 10Přàñíťh KümâřÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA Dissertation Sample On Organizational BehaviorDocument10 paginiMBA Dissertation Sample On Organizational BehaviorMBA DissertationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talent EngagementDocument11 paginiTalent EngagementSandhya RajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Job Satisfaction and Engagement A Complete GuideDe la EverandJob Satisfaction and Engagement A Complete GuideÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee OWNERSHIP and AccountabilityDocument5 paginiEmployee OWNERSHIP and Accountabilitytomor100% (1)

- Workforce Training CatalogDocument12 paginiWorkforce Training CatalogtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic BULLYING As A Supplementary Balanced Perspective On Destructive LEADERSHIPDocument12 paginiStrategic BULLYING As A Supplementary Balanced Perspective On Destructive LEADERSHIPtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCK Will Ai Make You A Better Leader 04 2018Document3 paginiMCK Will Ai Make You A Better Leader 04 2018tomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- LEADERSHIP Theory and PracticeDocument4 paginiLEADERSHIP Theory and Practicetomor20% (5)

- Development of A Private Sector Version of The TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP QUESTIONNDocument18 paginiDevelopment of A Private Sector Version of The TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP QUESTIONNtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Workshop On NeuroinformaticsDocument27 paginiInternational Workshop On NeuroinformaticstomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparing Outcome Measures Derived From Four Research DesignsDocument89 paginiComparing Outcome Measures Derived From Four Research DesignstomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amex Leadership ApproachDocument31 paginiAmex Leadership ApproachtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perspectives On Nonconventional Job Analysis MethodologiesDocument12 paginiPerspectives On Nonconventional Job Analysis MethodologiestomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comprehensive PERFORMANCE Assessment in English LOCAL GovernmentDocument14 paginiComprehensive PERFORMANCE Assessment in English LOCAL GovernmenttomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collaborative PMDocument19 paginiCollaborative PMtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articulating Appraisal SystemDocument25 paginiArticulating Appraisal SystemtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using Selection Optimization and Compensation To Reduce Job Family STRESSORSDocument29 paginiUsing Selection Optimization and Compensation To Reduce Job Family STRESSORStomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Job Relevance Commission and HRM EXPERIENCE PDFDocument9 paginiThe Effects of Job Relevance Commission and HRM EXPERIENCE PDFtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Uncertainty During Organizational ChangeDocument26 paginiManaging Uncertainty During Organizational ChangetomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dvelopment and Validation of A PERSONOLOGICAL Measure of Work DRIVEDocument25 paginiThe Dvelopment and Validation of A PERSONOLOGICAL Measure of Work DRIVEtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influences of Traits and Assessment Methods On HRMDocument16 paginiInfluences of Traits and Assessment Methods On HRMtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personality and Intelligence in Business PeopleDocument11 paginiPersonality and Intelligence in Business Peopletomor100% (1)

- Managerial Experience SND The MEASUREMENTDocument15 paginiManagerial Experience SND The MEASUREMENTtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Employees in the Service SectorDocument23 paginiManaging Employees in the Service Sectortomor100% (1)

- Measurement Equivalence and Multisource RatingsDocument27 paginiMeasurement Equivalence and Multisource RatingstomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investigating Different Sources of ORG CHANGEDocument16 paginiInvestigating Different Sources of ORG CHANGEtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leader ResponsivenessDocument15 paginiLeader ResponsivenesstomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internationalizing 360 Degree FedbackDocument22 paginiInternationalizing 360 Degree FedbacktomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incremental VALIDITY of Locus of CONTROLDocument21 paginiIncremental VALIDITY of Locus of CONTROLtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is Personality Related To Assessment Center Performance? - Journal of Business PsychologyDocument13 paginiIs Personality Related To Assessment Center Performance? - Journal of Business PsychologyDavid W. AndersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Image Theory and The APPRAISALDocument20 paginiImage Theory and The APPRAISALtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Do People Fake On Personality InventoriesDocument21 paginiDo People Fake On Personality InventoriestomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hierarchical Approach For Selecting PERSONALITYDocument15 paginiHierarchical Approach For Selecting PERSONALITYtomorÎncă nu există evaluări

- PMS: Performance Management System OverviewDocument13 paginiPMS: Performance Management System OverviewAbhi VkrÎncă nu există evaluări

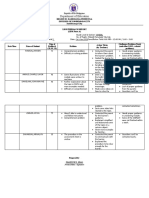

- To The On - SITE SUPERVISOR: Please Encircle The Appropriate Quantitative Equivalent Corresponding ToDocument8 paginiTo The On - SITE SUPERVISOR: Please Encircle The Appropriate Quantitative Equivalent Corresponding ToJean Marie VillaricoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pe Lesson Plan 3 Tgfu Gaelic FootballDocument6 paginiPe Lesson Plan 3 Tgfu Gaelic Footballcuksam27Încă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument7 paginiCurriculum DevelopmentCriza Mae Castor PadernalÎncă nu există evaluări

- L02-DLP-Key Concepts of EntrepreneurshipDocument2 paginiL02-DLP-Key Concepts of EntrepreneurshipAedrian ManabatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ncbts Domain 6Document10 paginiNcbts Domain 6elfe derama100% (1)

- Health Education, Models and MethodsDocument41 paginiHealth Education, Models and MethodsJesus Mario LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Template - Incisst - 2019 (Arabic)Document5 paginiTemplate - Incisst - 2019 (Arabic)فطري نورعينيÎncă nu există evaluări

- Portfolio Self Assessment Matrix 3Document1 paginăPortfolio Self Assessment Matrix 3api-341096580Încă nu există evaluări

- Effects OF Test Anxiety, Distance Education ON General Anxiety AND Life Satisfaction OF University StudentsDocument11 paginiEffects OF Test Anxiety, Distance Education ON General Anxiety AND Life Satisfaction OF University StudentsJorge Gamboa VelasquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Laboratory in Science Teaching and Learning: Avi HofsteinDocument2 paginiThe Role of Laboratory in Science Teaching and Learning: Avi HofsteinKho njÎncă nu există evaluări

- Department of Education: (Individual Report of Teacher)Document2 paginiDepartment of Education: (Individual Report of Teacher)Jessibel Alejandro100% (3)

- Week 3 Media and Information LiteracyDocument3 paginiWeek 3 Media and Information LiteracyVincent Bumas-ang Acapen50% (2)

- PWC Assessment Tests & Interview Preparation - 2022 - Practice4MeDocument11 paginiPWC Assessment Tests & Interview Preparation - 2022 - Practice4MeBusayo Folorunso100% (2)

- 2 - RP-0 - Participant Handout - v1Document4 pagini2 - RP-0 - Participant Handout - v1chaitanya kommuÎncă nu există evaluări

- FS 5 Episode 5Document6 paginiFS 5 Episode 5Janine CubaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1 Introduction To OBDocument32 paginiUnit 1 Introduction To OBsandbrtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Keys To Motivating TomorrowDocument7 paginiKeys To Motivating Tomorrowsalman_80Încă nu există evaluări

- Stages of Teacher DevelopmentDocument18 paginiStages of Teacher DevelopmentMohamad ShafeeqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analytical Summary - Teaching English To ChildrenDocument2 paginiAnalytical Summary - Teaching English To ChildrenMaría Fernanda Romero ZabaletaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Places in the City Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiPlaces in the City Lesson PlanRodica Cristina ChiricuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Review of "Language Assessment: Principles and Classroom PracticesDocument9 paginiCritical Review of "Language Assessment: Principles and Classroom PracticesIndah RamahatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructional Materials and Their Kinds of Instructional Aids and Their UsesDocument2 paginiInstructional Materials and Their Kinds of Instructional Aids and Their UsesJaizeill Yago-CaballeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Plan in MathematicsDocument2 paginiAction Plan in MathematicsPhilip Omar Famularcano100% (3)

- Psychiatric Nursing Terminologies - Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing - Mental Disorder PDFDocument22 paginiPsychiatric Nursing Terminologies - Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing - Mental Disorder PDFUttamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rubrik PentaksiranDocument1 paginăRubrik PentaksiranAngelinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depression and Sample Informative SpeechDocument1 paginăDepression and Sample Informative SpeechPrecy M AgatonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gotiangco, Christian Laine B. Beed-1CDocument1 paginăGotiangco, Christian Laine B. Beed-1CLaineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management OverviewDocument15 paginiManagement OverviewLeena AaronÎncă nu există evaluări

- FLCT Lesson Module 2Document25 paginiFLCT Lesson Module 2Cherry DerramasÎncă nu există evaluări