Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Crisis and Charisma in The California Recall Election

Încărcat de

tomorDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Crisis and Charisma in The California Recall Election

Încărcat de

tomorDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Leadership

http://lea.sagepub.com Crisis and Charisma in the California Recall Election

Michelle C. Bligh, Jeffrey C. Kohles and Rajnandini Pillai Leadership 2005; 1; 323 DOI: 10.1177/1742715005054440 The online version of this article can be found at: http://lea.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/1/3/323

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Leadership can be found at: Email Alerts: http://lea.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://lea.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations (this article cites 33 articles hosted on the SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms): http://lea.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/1/3/323

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

Crisis and Charisma in the California Recall Election

Michelle C. Bligh, Claremont Graduate University, USA, Jeffrey C. Kohles, California State University San Marcos, USA and Rajnandini Pillai, California State University San Marcos, USA

Abstract The 2003 California recall election represented a unique opportunity to study leadership in the context of what has been described in the popular media as an economic and political crisis. Participants (N = 311) reported their perceptions of the current situation in California and their tendency to attribute outcomes to leaders rather than situational factors (the Romance of Leadership Scale, or RLS). They subsequently watched video clips of the incumbent, the incumbent party challenger and the outside challenger, and rated their delivery style, charisma and expected effectiveness in ofce. Results indicate that both challengers were rated as more charismatic than the incumbent, and crisis perceptions were related to expected effectiveness ratings for all three candidates. In addition, higher charismatic delivery was associated with higher ratings of charisma and effectiveness. Finally, the RLS was signicantly related to ratings of the outside challengers charisma, and interacted with crisis perceptions to predict charisma ratings of both the incumbent party challenger and the outside challenger. Implications for the relationship between crisis and charisma, the importance of charismatic delivery style, and situational inuences on the RLS are discussed. Keywords charisma; crisis; election; leadership

Introduction

Charismatic leadership remains an important and widely studied phenomenon in organizational research. Empirically, charisma has been linked to a variety of important organizational outcomes, including performance, perceptions of leader effectiveness, subordinate effort, and satisfaction with leader performance (Avolio et al., 1988; Awamleh & Gardner, 1999; Bass, 1988, 1990). While charismatic leadership has been studied extensively over the last two decades, the eld has been criticized for focusing too heavily on leader-centered assumptions (Meindl, 1990), and overemphasizing the behavioral and personality characteristics of the charismatic leader (Dvir & Shamir, 2003). In addition, the eld has been criticized for neglecting the contextual and situational factors that may be more or less conducive to the

Copyright 2005 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) Vol 1(3): 323352 DOI: 10.1177/1742715005054440 www.sagepublications.com

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles

emergence of charismatic leadership (Beyer, 1999a, 1999b; Shamir & Howell, 1999). In light of these criticisms, the current study is an attempt to assess how multiple dimensions of the charismatic leadership process characteristics of the leader, the follower, and the situation interact to determine overall perceptions of charismatic leadership and effectiveness. The 2003 California recall election represented a unique and historical opportunity to study perceptions of leader effectiveness and charisma in the context of what was described as a serious political and economic crisis (Lupia, 2003: B1) in the state of California (Balz, 2003). California was the hub of the 1990s technology bubble, and it suffered the consequences of the stock market collapse of 20002, the national recession, and the jobless recovery. Further, as a result of voter initiatives, about 70 per cent of the states spending is earmarked in advance, limiting the governors ability to make trade offs in a crisis (Tyson, 2003). Together, these factors precipitated a massive budgetary crisis, which coupled with incumbent Democratic Governor Daviss widely cited non-charismatic personality (see Harper, 2003; Poole, 2003) and perceived inability to resolve the crisis, fueled voter discontent and triggered the recall. Against this contextual backdrop, the three main candidates in the California recall election were described as having very different leadership styles, and as possessing more or less charismatic qualities. For example, Governor Gray Davis was frequently cited in the media as lacking charisma (Bailey, 2003; Provance, 2003) or even possessing anti-charisma (Bevins, cited in Borowitz, 2003). Incumbent Democratic challenger Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante was described as uncharismatic as well. In contrast, as the Republican outside challenger, Austrian-born international movie star and California businessman Arnold Schwarzeneggers charismatic presence was repeatedly touted (Harper, 2003; Murphy, 2003). We sought to explore how the situation in the state of California in the fall of 2003 (i.e. the varying perceptions of the level of severity of the scal crisis and the need to elect a new leader) inuenced voters attributions about the candidates charisma and expected effectiveness once in ofce. Pearson and Clair (1998) dene a crisis as a low-probability, high-impact event that threatens the viability of the organization and is characterized by ambiguity of cause, effect, and means of resolution, as well as by a belief that decisions must be made swiftly (p. 59). Following Weber (1947), times of crisis have been argued to create an increased opportunity for charismatic leadership to emerge, and a number of studies have examined the effects of crisis on the leadership relationship (Bligh et al., 2004a, 2004b; Halverson et al., 2004; House et al., 1991; Hunt et al., 1999; Lord & Maher, 1991; Pillai, 1996; Pillai & Meindl, 1998; Stewart, 1967, 1976). Despite the growing number of studies that examine charisma in various crisis situations, our understanding of the interrelationships among charismatic processes and crisis situations is far from complete. In addition, the vast majority of work on crisis and charismatic leadership has been done in the laboratory, raising questions of both the generalizability and the ecological validity of these ndings. As Shamir and Howell (1999) point out: while crisis can facilitate the emergence of charismatic leadership, it is not a necessary condition for its emergence, nor for the success of such leadership (p. 258). However, in his review of charismatic leadership, Yukl (1999) contends that an uncertain and turbulent environment is a facilitating

324

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

condition for charismatic leadership, as it provides both threats and opportunities for the organization. Viewing political leadership in the recall election as a relationship between the candidates and California voters, we sought to explore how aspects of the situation, characteristics of the candidates, and follower attributes jointly contribute to the charismatic leadership relationship. Awamleh and Gardner (1999) point out that although leader- and follower-driven approaches may appear to be competing and mutually exclusive, they may actually offer complementary insights into leadership processes. We concur, and derive our theoretical approach from a tradition of charismatic research that emphasizes the role of the leader, the follower, and the situation in shaping the charismatic relationship (Awamleh & Gardner, 1999; Conger, 1989; Gardner & Avolio, 1998; Hughes et al., 2001; Klein & House, 1995; Shamir, 1995). Based on this tradition, the current study has three primary purposes: (1) to explore the relationship between perceptions of crisis and charismatic leadership; (2) to investigate whether participants tendencies to attribute outcomes to leaders are related to their assessments of charisma and expected effectiveness in ofce; and (3) to further our understanding of the role leader characteristics such as delivery style play on attributions of charisma and effectiveness.

Situational inuences on charismatic leadership

Shamir and Howell (1999) develop a number of propositions concerning characteristics of the situation that may be more or less conducive to the emergence of a charismatic leader. Three of these characteristics are relevant to the current study: (1) low organizational performance leading to the desire for new leadership; (2) the potential for a new leader to replace a somewhat non-charismatic leader; and (3) a relatively weak situation (Mischel, 1977) characterized by ambiguity and crisis. Each of these situational factors creates opportunities for both leaders and followers to act in ways that create a potentially fertile ground for charismatic leadership. We briey discuss each of these characteristics in the context of the 2003 California recall election. A long tradition of research dating back to Grusky (1963) suggests that leadership changes tend to occur more often when organizational performance is lower than expected. In such situations, leadership change often occurs because leaders are convenient scapegoats who can easily be blamed for low performance (Shamir & Howell, 1999). When opportunities exist for a new leader to be elected or appointed, as in the recall election, expectations for change among followers are likely to increase. Entering the organization, the new leader has numerous opportunities to re-frame and change existing interpretations, suggest new solutions to existing problems, and infuse a new spirit (p. 273). The fact that a recall election was precipitated, creating the potential for a new leader to provide an impetus for needed change, may thus be a powerful force driving charismatic attributions for the challengers. In addition, Shamir and Howell (1999) posit that new leaders are more likely to emerge as charismatic when they replace non-charismatic leaders. Given media accounts denoting the incumbent leader in this case as charismatically challenged (see for example Bailey, 2003; Borowitz, 2003; Provance, 2003), increased

325

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles

attributions of charismatic leadership to the challengers may be expected. Although this may seem counterintuitive given non-charismatic media depictions of the incumbent challenger, there is evidence to suggest that voters are more likely to evaluate a leader from their own political party as charismatic or transformational (Pillai et al., 2003). Therefore, Democrats may see the incumbent challenger as a more charismatically appealing choice in the context of a recall election in which the Governors performance is strongly questioned and the incumbent challenger is a lesser-known personality.

Hypothesis 1: Charismatic attributions will be signicantly higher for challengers (new leaders) than for the incumbent (an established leader)

Perceptions of crisis and ambiguity represent a third contextual factor relevant to the current study. Previous theoretical and empirical work suggests that the occurrence of a crisis may signicantly affect the relationship between leaders and followers (Bligh et al., 2004a, 2004b; House et al., 1991; Hunt et al., 1999; Pillai, 1996; Pillai & Meindl, 1991, 1998). Almost by denition, crisis situations engender perceptions of uncertainty and ambiguity (Pearson & Clair, 1998). In addition, numerous scholars have suggested that feelings of uncertainty may foster a greater appreciation for strong, decisive leadership often associated with charismatic leaders (Lord & Maher, 1991; Stewart, 1967, 1976; Yukl, 2002). Accepting a leaders interpretation of events and believing in his or her ability to deal with followers problems relieves followers of the psychological stress and loss of control created in the aftermath of a crisis (Bandura, 2001). As Shamir and Howell (1999) put it, post-crisis followers will readily, even eagerly, accept the inuence of a leader who seems to have high selfcondence and a vision that provides both meaning to the current situation and promise of salvation from the currently acute distress (p. 260). Shamir and Howell (1999) propose that crisis situations are special cases of what can more generally be termed weak situations, where performance goals cannot be easily specied. Drawing on Mischel (1977), Shamir and Howell dene strong situations as structured and clear contexts in which everyone similarly construes the situation and there are uniform expectations regarding appropriate responses. Weak situations, in contrast, are more ambiguous and less structured, and do not provide clear cues as to what would constitute effective leadership behaviors. The ambiguity experienced by people in unstructured situations, coupled with their tendency to look for externally derived cues to guide their behavior, together create opportunities for the emergence and inuence of charismatic leaders. Given this denition, the context of the recall election is an excellent example of a relatively unstructured situation, in which it may have been difcult for voters to accurately assess the most effective leadership actions or behaviors needed to resolve the budgetary crisis in California. It is important to note that in this election, the incumbent party challenger has a unique dual status that may have important effects on voters perceptions. Through his role as Lieutenant Governor and second in command of the state of California, Cruz Bustamante has characteristics representative of both incumbent and challenger. This situation is similar to one faced by many organizations as vice presidents

326

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

or other high-level executives are groomed and promoted from within for top executive positions. As new leaders, they may alternately be perceived as representatives of both the new and the old leadership, either welcomed as developers of a new vision or blamed for past failures and shortcomings. For followers who perceive a serious crisis situation that needs to be swiftly addressed, the incumbent party challenger may be evaluated as part of the current leadership establishment, responsible to a greater or lesser degree for the performance of the state or organization.

Hypothesis 2a: Perceptions of a state of crisis will be negatively related to ratings of charisma for incumbent party candidates, but positively related to ratings of charisma for outside challengers Hypothesis 2b: Perceptions of a state of crisis will be negatively related to ratings of expected effectiveness for incumbent party candidates, but positively related to ratings of expected effectiveness for outside challengers

Follower readiness for charisma The above argument for the inuence of weak situations on charismatic leadership emergence is consistent with follower-centered approaches to leadership that emphasize the function of charismatic leadership as a collective coping mechanism (Madsen & Snow, 1991; Meindl, 1993). Beyer (1999b) notes that strong needs in followers, such as a shared perception of a crisis or ambiguous situation, may drive them to socially construct and project qualities on a person to satisfy that need (p. 581). This collective desire to identify exceptional qualities in a leader suggests that the leaders qualities themselves may be actual or attributed. For example, Bligh et al. (2004a, 2004b) provide evidence that the crisis of 11 September 2001 set the stage for a transformation of the leadership relationship between President George W. Bush and the American public. Prior to the crisis, Bush was generally not seen as a strong, charismatic leader that people would easily place their faith in during times of crisis or external threat. However, their ndings suggest that the crisis affected both the Presidents rhetoric and the publics desire for a charismatically appealing leader, increasing the possibilities for the emergence of charismatic leadership. Pillai and Meindl (1991) also found that followers used charismatic criteria for emergent leadership more frequently in crisis situations than under less threatening conditions. They conclude that the attributes associated with charismatic leadership are more inuenced by contextual factors and follower perceptions than other types of leadership (i.e. transactional). An emphasis on follower readiness for charisma is consistent with a romance of leadership perspective, which emphasizes leadership as a social construction that is strongly inuenced by both followers and context (Meindl et al., 1985). Further, this approach emphasizes the situations and states of follower readiness in which leadership is more or less likely to emerge. Meindl (1990) suggests that some individuals exhibit a dispositional tendency to attribute outcomes to leaders across situations; the Romance of Leadership Scale (RLS) was developed to measure this tendency (Meindl & Ehrlich, 1988).

327

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles

According to Ehrlich and colleagues (1990), those with high scores on the RLS are more likely to attribute responsibility for outcomes to leaders and perceive them as inuential and charismatic. Meindl (1990) provides evidence that perceptions of charismatic leadership are likely to be greater in followers who attribute outcomes to leaders. Following our previous argument that in this situation, voters are likely to associate the states scal crisis and poor performance with the incumbent party candidates, and look to an outside challenger to solve the crisis and improve performance, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3a: Tendencies to attribute outcomes to leaders (high scores on the RLS) will be negatively related to perceptions of charisma for incumbent party candidates, but positively related to perceptions of charisma for outside challengers Hypothesis 3b: Tendencies to attribute outcomes to leaders (high scores on the RLS) will be negatively related to perceived expected effectiveness of incumbent party candidates, but positively related to perceptions of expected effectiveness for outside challengers

While the RLS has often been conceptualized as a dispositional tendency (see Awamleh & Gardner, 1999), Meindl (1995) also emphasizes potential situational input factors for the RLS, suggesting that the underlying assumption is that certain contextual features, quite independently of the personal attributes of followers, alter the nature of emergent leadership constructions (p. 335). He goes on to specify performance cues and perceptions of crisis as relevant situational factors, both of which represent important contextual variables in our study. Therefore, further research is necessary to uncover the extent to which the RLS represents a statelike versus trait-like tendency to attribute outcomes to leaders. In the current study, we theorize that scores on the RLS could potentially be inuenced by an individuals perceptions of a current state of crisis. Stated differently, perceptions of crisis may create a state of follower readiness, as reected by high scores on the RLS, in which followers are more likely to attribute greater levels of charisma and expected effectiveness to all leaders as compared to followers who do not perceive a state of crisis.

Hypothesis 4: Increased perceptions of crisis will strengthen the relationship between the RLS and attributions of charisma and expected effectiveness for all candidates

Leader characteristics: charismatic delivery style Characteristics of the leader also play an important role in the charismatic leadership relationship, and numerous scholars have advanced our understanding in this area (see Bass, 1985; Bass & Avolio, 1993; Bennis & Nanus, 1985; Conger & Kanungo, 1987, 1998; Deluga, 2001; House et al., 1988; Tichy & Devanna, 1986). Due to the large social distance between the Gubernatorial candidates and California voters, we focus specically here on delivery style as one of the primary sources of information voters have to assess the potential leadership skills of each candidate. Characteristics

328

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

of delivery such as intonation, timing, and gesture have been linked to audience receptivity of political messages (Heritage & Greatbatch, 1986), suggesting that the way that a political message is delivered both complements and reinforces the message and how it is received (Atkinson, 1984). A growing number of empirical studies have examined the relationship of delivery to charismatic attributions, suggesting that delivery is an important component of the charismatic leadership relationship (see for example Awamleh & Gardner, 1999; Howell & Frost, 1989; Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996). Holladay and Coombs (1993, 1994) suggest both content and delivery are important in predicting charismatic attributions in followers. Content is dened as the actual words a leader uses, while delivery is dened as the behavioral components of body movement, speech pattern, vocal tone, and intensity variation that characterize a speakers communications. Charismatic delivery behaviors thus include both verbal and nonverbal components, including eye contact, gestures, facial expressiveness, energy, uidity, and vocal tone variety. Taken together, these components comprise the physical presence a leader transmits through his or her communication style. While the relative effects of content and delivery have been examined (see Den Hartog & Verburg, 1997; Holladay & Coombs, 1993, 1994; Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996) debate remains regarding their relative importance, particularly in real world situations. On the basis of two laboratory studies, Holladay and Coombs (1993, 1994) conclude that delivery is relatively more important than content in predicting charismatic attributions. Awamleh and Gardner (1999) report similar ndings in a laboratory study in which undergraduates rated a ctitious CEO of a software company. They conclude that strength of delivery is an especially important determinant of perceptions of leader charisma and effectiveness (p. 345). Although the skillful use of charismatic content has been argued to be a critical component of charismatic leaders visionary behavior (Bligh et al., 2004a, 2004b; Emrich et al., 2001), a voters ability to distinguish levels of charismatic language in the traditional summative closing statement is difcult to assess with real life candidates, whose speeches are not systematically varied for charismatic content. For these reasons, in the present study we focus on the extent to which voters perceived the candidates to possess charismatic delivery. Although much has been written about the importance of delivery to charisma, few studies have been undertaken to examine the role of delivery outside of the laboratory. In leader-follower relationships characterized by greater social distance, in which followers may rely solely on the leaders verbal cues (Shamir, 1995), the relationship between delivery and charisma may be critically important in inuencing attributions of charisma. Therefore, across all candidates the following hypotheses were applicable:

Hypothesis 5a: Higher levels of charismatic delivery in the candidates speeches will be associated with higher ratings of charisma Hypothesis 5b: Higher levels of charismatic delivery in the candidates speeches will be associated with higher ratings of expected effectiveness

329

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles

Methods

Participants

Three hundred and eleven college students were recruited from graduate and undergraduate business and psychology courses in two southern California universities: a large public state school and a small private university. All data collection was completed in the four days immediately preceding the California recall election of 7 October 2003. Participants were between the ages of 19 and 57 (M = 26.97, SD = 7.12; Mdn = 25), and 52 per cent were female. Participants overwhelmingly listed California as their state of residence (96 per cent), and lived in the state an average of 19.7 years at the time of data collection. Respondents were primarily white (52.7 per cent), with 19.4 per cent Asian/Pacic Islander, 12.5 per cent Hispanic, 2.3 per cent black, 7.2 per cent multi-racial, and 4.6 per cent other. Political afliation was almost equally divided between Democrat (30.9 per cent) and Republican (37.2 per cent), with 20.7 per cent listing their party afliation as Independent and 11.2 per cent as other. Participants rated their political ideology as 3.60 (SD = 1.20) on a scale of 1 = very conservative to 6 = very liberal, indicating that they were somewhat liberal. Overall, our sample compares well with the results of an exit poll of 4,214 voters across California conducted by The Washington Post on 7 October 2003.

Procedure

Students were given a questionnaire packet that asked them to answer a series of questions assessing their perceptions of the current situation in California and their tendency to attribute outcomes to leaders. After completing Part One of the questionnaire, participants were asked to watch a short video clip of the incumbent Gray Davis, the incumbent party challenger Cruz Bustamante, or the outside challenger Arnold Schwarzenegger. For Bustamante and Schwarzenegger, participants watched the candidates closing statements from the major nationally televised Gubernatorial debate (24 September 2003). Because Gray Davis did not participate in this debate, we chose an equivalent closing statement from his debate less than one year earlier (7 October 2002) in his campaign for re-election to Governor. All three television clips showed the candidates addressing the camera directly for approximately two minutes. Respondents were advised that the study involved general opinions about political leaders and the purpose of showing the video clips was to remind respondents of the candidates in order to assess their general impressions of each. The videos were not intended to be a manipulation; they were intended to mimic the naturalistic setting in which voters might assess candidates leadership characteristics based on a relatively brief exposure to a leaders purposeful communication to the voters. After viewing each clip, participants completed a series of questions about each candidate as well as general background questions.

Measures

All measures were assessed on seven-point Likert scales with endpoints of Disagree Very Strongly and Agree Very Strongly.

330

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

Crisis In the absence of any appropriately validated measures for measuring perceptions of a state of crisis in California, we generated four items based on Pearson and Clairs (1998: 59) denition of crisis: (1) California is currently in a state of crisis; (2) The problems facing California are severe; (3) Swift decisions must be made in order to resolve the current state of affairs in California; and (4) It is unclear how to solve the current situation in California. Examination of the inter-item correlations suggested the deletion of item four, resulting in a three-item scale with an alpha of .78. Romance of leadership The tendency to view leadership as important in determining organizational outcomes was measured using the shortened, 11-item Version C of the Romance of Leadership Scale (Meindl & Ehrlich, 1988). A sample item is Sooner or later, bad leadership at the top will show up in decreased performance. Similar to the ndings of others (see Awamleh & Gardner, 1999), the RLS did not load on one factor. An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using principal components analysis with varimax rotation yielded a two-factor solution. Further examination of the factor structure revealed that the four reverse-coded items loaded on a separate factor. We thus deleted these items from the scale, resulting in a single factor solution for seven items (alpha = .81). Charisma and expected effectiveness The second part of the questionnaire included items from the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X Short Form; Bass & Avolio, 1995). A sample item is Articulates a compelling vision of the future. Although numerous concerns have been raised regarding the factor structure of the MLQ (Antonakis et al., 2003; Awamleh & Gardner, 1999; Bycio et al., 1995; Tejeda et al., 2001), it has been extensively utilized and validated across a wide variety of contexts (Bass & Avolio, 1993, 1995). We incorporated three four-item scales of charisma: Attributed Charisma (AC), Idealized Inuence (II), and Inspirational Motivation (IM). In addition, we also included four items to assess expectations of leader effectiveness (EF). Three separate factor analyses were run on each of the respective candidates and results were compared for likeness of factor loadings. EFA utilizing principal components analysis with varimax rotation yielded two factors, and these results differed only slightly from those of Awamleh and Gardner (1999). Factor 1 included seven items, and is similar to the effectiveness factor found by Awamleh and Gardner, with the addition of the fourth effectiveness item (Is effective in representing California to higher authorities). Factor 2 included all of Awamleh and Gardners perceived charisma items with the addition of the item Is charismatic and the subtraction of the fourth effectiveness item. All factors had loadings higher than 3.0. Based on these results, we collapsed the AC, II, and IM scales into a single measure of perceived charisma. As the conceptual and empirical rationale for doing so has been stated elsewhere (p. 354), we will not reiterate it here. In addition, we dropped the three charisma items that failed to load onto the second factor to form a fouritem measure of effectiveness. A subsequent EFA produced a two-factor solution. Reliability coefcients for perceived charisma were .87 for Davis, .92 for

331

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles

Bustamante, and .87 for Schwarzenegger; expected effectiveness alphas were .96 for Davis, .96 for Schwarzenegger, and .97 for Bustamante. Charismatic delivery style Measures of charismatic delivery style were adopted from Holladay and Coombss (1993, 1994) studies and from theoretical arguments put forth by Awamleh and Gardner (1999) and Howell and Frost (1989). Holladay and Coombss measures are derived from Nortons (1983) communicator style construct; however, only the subconstructs of attentive, friendly, dominant, dramatic, and relaxed predicted charismatic attributions across Holladay and Coombss (1993, 1994) two experiments. For the purposes of this study, only these styles were utilized, resulting in the 15-item scale listed in Table 1. Because the primary elements of charismatic delivery have not been extensively validated, we again performed a principal components EFA with varimax rotation, which yielded the two-factor solution reported in Table 1. Examination of the two factors revealed one factor consisting of friendly, attentive, and relaxed; Factor 2 included items reecting a dramatic and dominant delivery style. Alphas for the friendly, attentive, and relaxed delivery style were .87 for Davis, .87 for Bustamante, and .86 for Schwarzenegger. Alphas for the dramatic and dominant delivery style were .84 for Davis, .82 for Bustamante, and .83 for Schwarzenegger. Background and control variables Party identication is also likely to play an important role in attributions of charisma and expected effectiveness. In the absence of any compelling reasons to do

Table 1 EFA of charismatic delivery items

Davis F1 Friendly, Attentive, and Relaxed 1. Maintains eye contact with the audience 2. Is uent in his speaking style 3. Is an open communicator 4. Is articulate 5. Is relaxed 6. Is a very good communicator 7. Is a friendly communicator Dramatic and Dominant 8. Has an assertive voice 9. Is vocally a loud communicator 10. Dramatizes a lot 11. Uses a lot of facial expressions 12. Uses a lot of hand gestures 13. Is dramatic 14. Is expressive 15. Leaves an impression on people Eigenvalues F2 Schwarzenegger F1 F2 Bustamante F1 F2

.54 .68 .69 .76 .71 .82 .76 .33 .39 .03 .36 .21 .22 .56 .35 6.56

.25 .24 .35 .20 .12 .24 .13 .58 .48 .82 .64 .52 .84 .60 .44 1.39

.55 .55 .70 .74 .73 .80 .83 .34 .43 .05 .23 .12 .12 .56 .26 6.02

.24 .25 .23 .16 .06 .07 .01 .64 .49 .83 .67 .57 .86 .59 .65 2.06

.51 .79 .71 .73 .70 .84 .78 .27 .36 .05 .19 .03 .20 .56 .38 6.33

.07 .07 .38 .05 .00 .24 .23 .58 .39 .72 .75 .68 .77 .57 .70 1.84

332

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

otherwise, a voters natural tendency is to vote for candidates of the party with which he or she identies (Pillai et al., 2003). Shamirs (1994) study of the 1992 Israeli elections demonstrates that a voters ideological position strongly inuences a leaders perceived charisma. In addition, Pillai et al.s (2003) ndings suggest that voters are more likely to evaluate a leader from their own political party as charismatic or transformational, and party afliation has an important inuence on voting behavior (see also Pillai & Williams, 1998). Overall, this evidence suggests that voters are likely to support and identify with a leader who articulates a vision that advances their partys agenda. For this reason, the questionnaire also included questions assessing political party afliation, voting intentions, prior voting behavior, ideology, and frequency of reading the newspaper, watching news on television, and visiting news-related websites. Respondents indicated their party afliation as Democratic, Republican, Independent, or other, and indicated their intent to vote in the recall election and whether they had previously voted for Davis. Responses to frequency of media exposure were dichotomized to form a single measure of news media exposure (0 = combined television, web, or newspaper exposure is less than several times per week; versus 1 = combined television, web, or newspaper exposure is more than several times per week; M = .78; SD = .41). Participants also completed ve general political knowledge items adopted from Kathlene (1989): (1) if they voted in the last election; (2) what political party currently has the most members in the US Senate; (3) the length of term of ofce for a US Senator; (4) the number of US Senators; and (5) what percentage of US Senators are women. Participants responses were dichotomously coded and added together to create a knowledge score ranging from 0 = no questions correct (not very knowledgeable) to 5 = all questions correct (very knowledgeable). The average knowledge score was 1.93 (SD = 1.37). Finally, participants were asked to respond to standard demographic questions, including age, sex (coded 1 = male and 0 = female), and ethnicity (coded as 1 = white and 0 = all others). ANOVAs revealed differences between participants from the large public university and the small private university on political ideology and candidate ratings. Further analyses revealed signicant relationships among age, gender, ethnicity, political knowledge, political afliation, ideology, and media exposure on the dependent variables. Because we are broadly interested in how overall perceptions of the current situation, leadership characteristics, and follower perceptions contributed to attributions of charisma and expected effectiveness, we included these background variables as controls in our analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of key variables are listed in Tables 2 to 4. Mean perceptions of crisis were 5.44 out of 7 (SD = .95), indicating many respondents agreed with media accounts that the state of California was currently in a state of crisis at the time of the recall election. Alternately, this result may also indicate that the media successfully created the perception of crisis, regardless of the actual state of affairs. We found no signicant effects based on the sequence of presentation of the videotapes.

333

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

334

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

1(3) Articles

Table 2 Descriptive statistics and correlations for Davis

Variables 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afl. Dem. Prior vote: Davis Vote Davis Crisis RLS Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Charisma Effectiveness Mean 26.97 .48 .54 1.12 .78 1.93 3.60 .31 .18 .20 5.44 4.88 4.02 3.48 3.79 3.17 s.d. 7.12 .50 .50 .33 .41 1.37 1.20 .46 .38 .40 .95 .88 1.05 .89 1.04 1.44 1 . .00 .19 .09 .13 .25 .03 .00 .20 .20 .01 .11 .01 .10 .03 .03 2 . .03 .10 .07 .19 .17 .17 .03 .03 .05 .04 .03 .00 .01 .05 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

. .03 .04 .20 .13 .13 .12 .04 .02 .18 .07 .11 .04 .08

. .02 .04 .16 .16 .01 .01 .02 .05 .02 .15 .03 .16

. .17 .05 .01 .02 .02 .04 .12 .00 .04 .03 .04

. .09 .05 .24 .13 .06 .18 .11 .10 .05 .04

. .43 .22 .30 .23 .08 .11 .06 .02 .28

. .38 .26 .15 .09 .09 .02 .10 .25

. .47 .19 .13 .07 .05 .15 .24

. .23 .26 .15 .11 .22 .33

. .45 . .06 .06 .03 .03 .10 .00 .30 .14

. .69 .56 .42

. .57 .37

. .60

Note: Df = 309. Correlations greater than .11 are signicant at p < .05, and correlations greater than .15 are signicant at p < .01.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Table 3 Descriptive statistics and correlations for Schwarzenegger

Variables 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afl. Rep. Prior vote: Davis Vote Schwarzenegger Crisis RLS Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Charisma Effectiveness Mean 26.97 .48 .54 1.12 .78 1.93 3.60 .37 .18 .46 5.44 4.88 5.17 5.37 5.16 4.47 s.d. 7.12 .50 .50 .33 .41 1.37 1.20 .48 .38 .50 .95 .88 .93 .85 .94 1.39 1 . .00 .19 .09 .13 .25 .03 .00 .20 .01 .01 .11 .02 .12 .01 .12 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

. .03 . .10 .03 .07 .04 .19 .20 .17 .13 .09 .26 .03 .12 .21 .24 .05 .02 .04 .18 .05 .14 .03 .17 .10 .12 .12 .12

. .02 .04 .16 .13 .01 .15 .02 .05 .05 .16 .06 .12

. .17 .05 .01 .02 .07 .04 .12 .02 .02 .03 .00

. .09 .09 .24 .13 .06 .18 .08 .14 .09 .00

. .45 .22 .30 .23 .08 .09 .00 .18 .25

. .29 .43 .22 .16 .23 .13 .21 .41

. .20 .19 .13 .11 .10 .24 .28

. .06 .01 .32 .16 .39 .59

. .45 . .17 .17 .12 .12 .15 .11 .23 .19

. .56 .57 .58

. .52 .32

. .60

Note: Df = 309. Correlations greater than .11 are signicant at p < .05, and correlations greater than .15 are signicant at p < .01.

335

Leadership

336

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

1(3) Articles

Table 4 Descriptive statistics and correlations for Bustamante

Variables 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afl. Dem. Prior vote: Davis Vote Bustamante Crisis RLS Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Charisma Effectiveness Mean 26.97 .48 .54 1.12 .78 1.93 3.60 .31 .18 .16 5.44 4.88 5.26 3.95 4.67 4.01 s.d. 7.12 .50 .50 .33 .41 1.37 1.20 .46 .38 .36 .95 .88 .87 .95 1.04 1.47 1 . .00 .19 .09 .13 .25 .03 .00 .20 .11 .01 .11 .02 .02 .05 .06 2 . .03 .10 .07 .19 .17 .17 .03 .10 .05 .04 .06 .11 .15 .10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

. .03 .04 .20 .13 .13 .12 .17 .02 .18 .05 .11 .09 .25

. .02 .04 .16 .16 .01 .05 .02 .05 .12 .07 .10 .09

. .17 .05 .01 .02 .07 .04 .12 .00 .02 .03 .10

. .09 .05 .24 .07 .06 .18 .02 .05 .05 .15

. .43 .22 .26 .23 .08 .24 .20 .29 .39

. .38 .37 .15 .09 .18 .12 .30 .33

. .32 .19 .13 .09 .03 .12 .11

. .19 .04 .37 .27 .41 .50

. .45 . .05 .04 .04 .03 .14 .04 .25 .05

. .62 .66 .56

. .64 .47

. .74

Note: Df = 309. Correlations greater than .11 are signicant at p < .05, and correlations greater than .15 are signicant at p < .01.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

Hypothesis 1 stated that both challengers would be rated as more charismatic than the incumbent. Results indicate that this was indeed the case. The outside challenger was rated as signicantly more charismatic than both the incumbent (MD = 1.37, SD = 1.50, (t(308) = 16.82, p < .001) and the incumbent party challenger (MD =.49, SD = 1.45, (t(309) = 5.93, p < .001). In addition, the incumbent party challenger was rated as signicantly more charismatic than the incumbent (MD = .88, SD = 1.30, (t(309) = 11.84, p < .001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is strongly supported. In order to examine the remaining hypotheses, we conducted hierarchical regressions comprising four steps for each of the candidates (see Tables 5 to 8). Step 1 examined the effects of the demographic control variables (age, gender, ethnicity, and school). Step 2 added the effects of political knowledge, exposure to news media, party afliation, political ideology, prior voting, and intent to vote. Step 3 added the

Table 5 Hierarchical regression results for Davisa

Model 1 Dependent Variable Charisma Independent Variable Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation: Dem. Prior vote: Davis Intent to vote: Davis Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s Effectiveness Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation: Dem. Prior vote: Davis Intent to vote: Davis Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s

a

Model 2 Beta .10 .01 .00 .05 .00 .09 .09 .06 .07 .25*** SE B .01 .13 .13 .18 .15 .05 .06 .15 .19 .17

Model 3 Beta .05 .00 .04 .10 .01 .03 .16** .06 .03 .16** .15** .07 .31*** .35*** .44 42.69*** SE B .01 .10 .10 .15 .12 .04 .05 .12 .15 .14 .06 .06 .06 .08

Model 4 Beta .05 .01 .05 .09 .00 .02 .16** .06 .03 .16** .17** .07 .31*** .34*** .07 .44 1.77 SE B .01 .10 .10 .15 .12 .04 .05 .12 .15 .14 .06 .06 .06 .08 .04

Beta .06 .01 .01 .04

SE B .01 .12 .13 .18

.00 .31 .00 .05 .07 .17** .01 .17 .17 .25

.08 3.85*** .05 .01 .03 .14*** .04 .06 .12 .10 .07 .28*** .01 .16 .17 .23 .20 .06 .08 .20 .25 .23

.02 .02 .00 .16** .03 .03 .05 .10 .04 .19*** .27*** .03 .26*** .16* .40 20.84***

.01 .14 .15 .21 .18 .06 .07 .18 .22 .21 .09 .09 .09 .11

.02 .01 .00 .16** .03 .03 .05 .10 .04 .19*** .28*** .03 .26*** .16* .05 .40 .77

.01 .14 .15 .21 .18 .06 .07 .18 .22 .21 .09 .09 .09 .11 .06

.04 2.52*

.21 9.99***

N = 311. Beta coefcients are standardized. p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

337

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles Table 6 Hierarchical regression results for Schwarzeneggera

Model 1 Dependent Variable Charisma Independent Variable Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation: Rep. Prior vote: Davis Intent to vote: Schwarzenegger Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s Effectiveness Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation: Rep. Prior vote: Davis Intent to vote: Schwarzenegger Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s

a

Model 2 Beta .03 .02 .01 .01 .04 .10 .00 .01 .19** .34*** SE B .01 .15 .15 .21 .17 .06 .07 .18 .21 .16

Model 3 Beta .05 .06 .04 .05 .06 .04 .08 .08 .14** .21*** .06 .12* .28*** .37*** .50 37.03*** SE B .01 .09 .10 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .10 .05 .06 .06 .07

Model 4 Beta .05 .05 .02 .05 .07 .03 .09 .08 .14** .20*** .03 .13* .27*** .38*** .13* .52 7.36** SE B .01 .09 .10 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .10 .05 .06 .06 .07 .04

Beta .05 .11 .14* .05

SE B .01 .12 .12 .17

.04 2.44* .14* .12 .14* .12 .01 .17 .18 .26

.21 9.20*** .09 .02 .01 .03 .01 .04 .01 .17** .11 .49*** .01 .15 .15 .21 .17 .06 .07 .18 .21 .16

.09 .07 .02 .03 .01 .07 .03 .12* .07 .37*** .07 .02 .37*** .09 .59 26.74***

.01 .10 .10 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .10 .05 .06 .06 .07

.09* .07 .03 .03 .01 .08 .03 .12* .07 .36*** .08 .03 .37*** .09 .06 .59 1.90

.01 .12 .13 .18 .15 .05 .06 .15 .18 .14 .07 .08 .08 .09 .05

.06 4.43**

.41 25.50***

N = 311. Beta coefcients are standardized. < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

main effects of crisis perceptions, delivery styles, and the Romance of Leadership Scale. Finally, Step 4 added the hypothesized moderator effect (Crisis X RLS). Following the procedure outlined in Villa et al. (2003), we rst standardized each variable and then constructed a cross product that was entered into Step 4 of each regression. Thus, the regression analyses consider the potentially confounding effects of all control variables before assessing main effects and the potential moderating effects of crisis perceptions. Increments in R2, changes in F, and standardized betas were examined to determine if signicant variance is accounted for by the addition of the moderated variables (Rs2 Rs1; see Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Hypothesis 2a stated that perceptions of a state of crisis would be signicantly related to ratings of charisma. Results indicate that crisis perceptions signicantly

338

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al. Table 7 Hierarchical regression results for Bustamantea

Model 1 Dependent Variable Charisma Independent Variable Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation: Dem. Prior vote: Davis Intent to vote: Bustamante Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s Effectiveness Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation: Dem. Prior vote: Davis Intent to vote: Bustamante Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s

a

Model 2 Beta .06 .07 .02 .02 .01 .01 .12 .17* .08 .35*** SE B .01 .12 .12 .18 .15 .05 .06 .15 .18 .18

Model 3 Beta .04 .04 .01 .01 .01 .07 .00 .16*** .03 .14** .04 .04 .36*** .35*** .59 52.64*** SE B .01 .09 .09 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .14 .05 .06 .07 .06

Model 4 Beta .04 .04 .02 .01 .01 .06 .00 .16*** .02 .14** .06 .04 .36*** .35*** .09* .61 4.02* SE B .01 .09 .09 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .14 .05 .06 .07 .06 .04

Beta .04 .15* .09 .08

SE B .01 .13 .13 .19

.04 2.91* .03 .09 .26*** .08 .01 .18 .18 .27

.25 11.68*** .03 .02 .13* .01 .08 .09 .25*** .13* .05 .39*** .01 .15 .16 .23 .19 .06 .07 .19 .22 .23

.01 .03 .14** .01 .07 .11* .14** .14** .04 .22*** .16*** .01 .29*** .19*** .57 24.90***

.01 .13 .14 .19 .16 .05 .06 .17 .19 .21 .08 .08 .10 .08

.01 .03 .13** .02 .08 .10* .14** .14** .03 .22*** .18*** .01 .29*** .18*** .07 .57 2.67

.01 .13 .14 .19 .16 .05 .06 .17 .19 .21 .08 .08 .10 .08 .06

.09 6.43***

.40 22.24***

N = 311. Beta coefcients are standardized. p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

and negatively inuenced perceptions of charisma for the incumbent (b = .17, p < .01) but were not signicant predictors of charisma for the incumbent party challenger (b = .06, p = .21) or the outside challenger (b = .03, p = .61). Thus, Hypothesis 2a is only partially supported, suggesting that perceptions of crisis negatively impacted perceptions of the charisma of the current leadership. Results indicate that perceptions of a state of crisis signicantly inuenced expectations of effectiveness for all three candidates (Hypothesis 2b). In the case of the incumbent party candidates, there was a signicant negative effect (Davis: b = .28, p < .001, Bustamante: b = .18, p < .001); however, this effect was positive for the outside challenger (Schwarzenegger: b = .08, p < .10). Hypothesis 2b is thus supported: perceptions of crisis were negatively associated with expected

339

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles Table 8 Final model hierarchical regression results for all three candidates

Davis Dependent Variable Charisma Independent Variable Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation Prior vote Intent to vote Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s Beta .05 .01 .05 .09 .00 .02 .16** .06 .03 .16** .17** .07 .31*** .34*** .07 .44 1.77 Davis Dependent Variable Effectiveness Independent Variable Age Gender Ethnicity School Media exposure Political knowledge Political ideology Political afliation. Prior vote Intent to vote Crisis Romance of leadership Friendly delivery Dramatic delivery Crisis X RLS Rs F for change in R s

a

Schwarzenegger Beta .05 .05 .02 .05 .07 .03 .09 .08 .14** .20*** .03 .13* .27*** .38*** .13* .52 7.36** Schwarzenegger Beta .09 .07 .02 .03 .01 .07 .03 .12* .07 .37*** .07 .02 .37*** .09 .59 26.74*** SE B .01 .10 .10 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .10 .05 .06 .06 .07 SE B .01 .09 .10 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .10 .05 .06 .06 .07 .04

Bustamante Beta .04 .04 .01 .01 .01 .07 .00 .16*** .03 .14** .04 .04 .36*** .35*** .59 52.64*** Bustamante Beta .01 .03 .14** .01 .07 .11* .14** .14** .04 .22*** .16*** .01 .29*** .19*** .57 24.90*** SE B .01 .13 .14 .19 .16 .05 .06 .17 .19 .21 .08 .08 .10 .08 SE B .01 .09 .09 .13 .11 .04 .04 .11 .13 .14 .05 .06 .07 .06

SE B .01 .10 .10 .15 .12 .04 .05 .12 .15 .14 .06 .06 .06 .08 .04

Beta .02 .01 .00 .16** .03 .03 .05 .10 .04 .19*** .28*** .03 .26*** .16* .05 .40 .77

SE B .01 .14 .15 .21 .18 .06 .07 .18 .22 .21 .09 .09 .09 .11 .06

N = 311. Beta coefcients are standardized. p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

effectiveness of the current leadership and positively associated with the outside challengers expected effectiveness. In Hypothesis 3a, we predicted that tendencies to attribute outcomes to leaders (high scores on the RLS) would be signicantly related to perceptions of charismatic leadership. This was only the case for the outside challenger, indicating that those individuals who were more likely to attribute outcomes to leaders were also (perhaps optimistically) more likely to see charismatic attributes in the potential incoming leadership (Davis: b = .07, p = .23; Schwarzenegger: b =.13, p < .05; Bustamante: b = .04, p = .40). The RLS was not signicantly related to ratings of expected

340

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

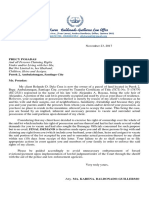

effectiveness for any of the candidates (Davis: b = .03, p = .61; Schwarzenegger: b = .03, p = .65; Bustamante: b = .01, p = .86), providing no support for Hypothesis 3b. In Hypotheses 4, we predicted that increased perceptions of crisis would strengthen the relationship between the RLS and attributions of charisma and expected effectiveness for all candidates. We found two signicant moderator effects, explaining an additional 2 per cent of the variance in charisma for both challengers (Schwarzenegger: b = .13, p < .05; Bustamante: b = .09, p < .05). Thus, there was partial support for Hypothesis 4. The moderating effect of perceptions of crisis on the RLS and charismatic perceptions for all three candidates is shown in Figure 1 (A to C) (based on Aiken & West, 1991). To aid the interpretation of the interaction term, we used a median split to divide the sample into high and low perceptions of crisis. Figure 1(B) suggests that in the case of the outside challenger, individuals with high perceptions of crisis and higher scores on the RLS were more likely to see him as charismatic. This relationship disappears, however, for voters who did not perceive the state was in a crisis. In the case of the incumbent party challenger, however, high perceptions of crisis and higher RLS scores were associated with lower charisma scores; again, this relationship disappeared for respondents with lower perceptions of crisis (see Figure 1(C)). Hypothesis 5a stated that higher levels of charismatic delivery in the candidates speeches would be associated with higher ratings of charisma. Results indicate that a friendly, attentive, and relaxed delivery style was strongly related to subsequent charismatic attributions for all three candidates, even after controlling for all other factors (Davis: b = .31, p < .001; Schwarzenegger: b = .27, p < .001; Bustamante: b = .36, p < .001). In addition, a dramatic and dominant delivery style was signicantly associated with charismatic attributions for all three candidates (Davis: b = .34, p < .001; Schwarzenegger: b = .38, p < .001; Bustamante: b = .35, p < .001). Hypothesis 5b proposed that higher levels of charismatic delivery would also be associated with higher ratings of expected effectiveness. Analyses revealed that a friendly, attentive, and relaxed delivery style was signicantly associated with expected effectiveness for all three candidates (Davis: b = .26, p < .001; Schwarzenegger: b = .37, p < .001; Bustamante: b = .29, p < .001). In addition, a dramatic and dominant style was also related to perceptions of likely effectiveness in ofce for all three candidates (Davis: b = .16, p < .05; Schwarzenegger: b = .09, p < .10; Bustamante: b = .18, p < .001). Thus, Hypotheses 5a and 5b are supported.

Discussion

Shamir and Howell (1999) contend that the literature on charismatic leadership has neglected the organizational context in which such leadership is embedded (p. 257). The 2003 California recall election is an interesting contextual backdrop against which to examine the role of situational inuences, follower characteristics, and leadership delivery styles on perceptions of charisma and effectiveness. We conducted the study immediately prior to a historical Gubernatorial recall election, in a crisis situation with real leaders and followers who were faced with a very important choice that directly impacted Californias leadership. Thus, we feel this study provides important theoretical insights into the relationships among crisis,

341

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles Figure 1 Moderating inuence of perceptions of crisis on the relationship between RLS and charisma (A)

Davis

7 6 5

Charisma

4 3 2 1 0

Romance of Leadership Scale

Linear (Low Crisis) Linear (High Crisis)

(B)

Schwarzenegger

7 6 5

Charisma

4 3 2 1 0

Romance of Leadership Scale

Linear (Low Crisis) Linear (High Crisis)

(C)

Bustamante

7 6

Charisma

5 4 3 2 1 0

Romance of Leadership Scale

Linear (Low Crisis) Linear (High Crisis)

342

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

delivery style, and charisma in a real life context with signicant consequences for followers. Specically, we will highlight the potential theoretical contributions of our study for the following areas: 1. The importance of situational inuences on charismatic attributions; 2. The relationship between crisis and charisma; 3. Potential moderators of the relationship between delivery style and charisma (including social distance, gender, culture, and leader experience); 4. Situational inuences on tendencies to attribute outcomes to leaders (the RLS); 5. The relationship between charisma and effectiveness. The fact that both challengers were rated as more charismatic across all potential voters (Hypothesis 1) provides preliminary support for Shamir and Howells (1999) propositions concerning the importance of contextual inuences on charismatic leadership emergence. Specically, low organizational performance and the desire for new leadership, coupled with an incumbent leader with little charismatic appeal, created a fertile ground for charismatic emergence in the challengers. In addition, perceptions of crisis were signicantly associated with decreased ratings of charisma and effectiveness for the incumbent leadership (Hypotheses 2a and 2b), suggesting that voters who perceived a crisis situation in California were less likely to see the Governor as a strong, charismatic leader who was capable of turning the performance of the state around. Thus, our results are only partially consistent with previous research ndings that suggest perceptions of crisis create a fertile ground for attributions of charisma. In fact, in the case of current leaders facing lower levels of performance than expected, a crisis situation may actually lead to decreased perceptions of charisma, as followers place the blame for the crisis on the incumbent leadership (see also Pillai & Meindl, 1998). Despite individual differences in the communication style of each of the three candidates, our results suggest two important components of delivery style are relevant to charismatic leadership: a friendly, attentive, and relaxed style, and a dramatic and dominant style. Further research should continue to work toward the development of reliable and valid scales to measure charismatic delivery across a wide variety of leadership situations. Specically, existing theory may inadequately address the relative importance of these two delivery components across situations of varying social distance (Shamir, 1995). It is possible that our ndings reecting the importance of a dramatic and dominant style may be a function of the large social distance between the Gubernatorial candidates and the voters. For example, a dramatic and dominant style may not be well received by subordinates of middle and lower level managers, or such a style may be called for in the context of visionary messages but not in everyday interactions. It is also likely that during a crisis, when followers are psychologically aroused, they are more likely to be receptive to a delivery style that is dramatic and dominant. In addition, current theory largely neglects the role of gender in the relationship between delivery style and charismatic attributions. It may well be that certain expectations of delivery style become attached to male and female leaders, and these expectations may also be different for male and female followers. Similarly, a

343

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles

dramatic and dominant style may be less appropriate in some cultural contexts, as this type of inuence may be viewed as inappropriate or too individualistic in more collectivistic cultures. Together, characteristics of the leader and the situation may thus importantly inuence the type of delivery style that is most predictive of charismatic attributions. Our ndings also suggest further theoretical development concerning another important factor: leader experience. Specically, future research should examine the strength and consistency of the relationship between delivery style, charisma and effectiveness across leaders with varying levels of experience, tenure, and established public leadership records. Charismatic delivery may be more strongly related to these ratings in the case of new, relatively unknown leaders than leaders with longer tenure and well-publicized stories of success and failure in the popular press. Where candidates or executives are less well known, charismatic delivery style may be more critical in inuencing attributions of charisma and effectiveness than in the case of candidates and executives with well-known track records. Our ndings are also relevant to theoretical and empirical work regarding the RLS, which was not signicantly related to perceptions of leader charisma and effectiveness across all three candidates (with the exception of charismatic ratings of Schwarzenegger). The RLS was initially developed to assess dispositional tendencies to attribute outcomes to leaders. However, a number of situational factors may have inuenced scores on the RLS, and Meindl (1995) suggests that crisis situations and performance cues may be two important input factors. In our analyses, the strong correlation between perceptions of crisis and the RLS (r = .45, p < .001) suggests that the two variables are signicantly related. One explanation for these ndings is that the situational effect of the crisis was so strong that it overrode the effect of the RLS on the dependent variables. In other words, the effect of the crisis situation may have cued increased attributions of charisma and effectiveness, regardless of an individuals dispositional tendencies. Another possibility is that the recall election itself acted as a strong performance cue for voters. The fact that the recall election was precipitated during a time of low performance in the state of California may have inuenced voters to assign more blame for that performance onto the current leadership. In the context of an election particularly the special context of a recall election less than a year after the current leadership was elected to a second term the low performance of the state is likely to be particularly salient, as are attributions that leadership must be at least partially to blame. Taken together, our ndings suggest that the RLS may be more situationally inuenced than has previously been thought (see also Awamleh & Gardner, 1999), and future research may benet from examining the extent to which scores on the RLS are impacted by various aspects of the situation. Specically, contextual inuences proposed by Shamir and Howell (1999), such as leader hierarchical level, organizational performance, or weak versus strong situations might be combined with longitudinal RLS measures to assess the extent to which different situations create different degrees of follower readiness for charismatic leadership. Finally, it is important to comment on the relationship between the two dependent variables in this study, charisma and expected effectiveness. Theoretically, these two constructs are quite distinct, and they have been separately dened and measured in many empirical studies of leadership (Atwater et al., 1997; Awamleh & Gardner,

344

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

1999; Deluga, 1998, 2001). Operationally, however, particularly when researchers assess followers attributions of charisma and expected effectiveness, they are likely to be less distinct. As we found in the current study, there may often be a strong halo effect, in that candidates who followers perceive as more charismatic tend to be the same leaders that they expect to be effective. This relationship reects another type of romance of leadership (Meindl et al., 1985) in which followers confronted with charismatic leaders are likely to attribute higher performance to them as well. In many ways, this theoretical distinction may parallel the ongoing discussion concerning management and leadership that has been extensively discussed in the leadership literature. As followers, particularly in a crisis situation, we seem to crave both charismatic leaders as well as effective managers: that is, leaders who can both save the day and get the job done.

Limitations and directions for future research

Although some may argue that the Schwarzenegger phenomenon is unique to this particular situation, our results underscore a long tradition in the crisis and charisma literature that has documented the yearning for a charismatic larger than life personality in a crisis (for example FDR and Churchill during WWII, Juan Pern in Argentina, Lee Iacocca during the Chrysler crisis; see also Willner, 1984). Current examples can be found in the business realm as well: when the CEO of Motorola, Chris Galvin, recently stepped down in the midst of a downturn for the legendary organization, the business press called for a charismatic leader who would turn around the companys fortunes (see Maney, 2003; Wolinsky, 2003). Historically, California has been receptive to larger than life movie star charismatic candidates (e.g. Ronald Reagans two terms as Californias Governor), and internationally, it is not uncommon for movie stars to be in politics (see Rimban, 2002), suggesting that the Arnold Schwarzenegger situation is not entirely unique. In light of these examples, we feel that having a personality like Schwarzenegger as a challenger to the incumbent only served to highlight this aspect of the relationship between crisis and charisma in a real world setting. This study is one of the few attempts to examine the effects of a crisis on charismatic perceptions of both incumbent and challengers in a naturally occurring environment, and provides additional evidence that followers desire for a post-crisis charismatic personality is a fairly prevalent and generalizable phenomenon. In the context of the current backlash against charismatic CEOs in the wake of recent corporate scandals (e.g. Bernie Ebbers of WorldCom, Calisto Tanzi of Parmalat, Jean Marie Messier of Vivendi Universal) and the emphasis on humilitybased Level 5 leadership (Collins, 2001), it is interesting to note that charismatic leaders are still seen as possible saviors in a crisis situation. Other business situations may be protably examined in light of our ndings as well, such as times of postmerger leadership change, CEO succession, or even managerial changes in middle and lower levels of the organization. It is easy to imagine situations in which lowered performance and the desire for new leadership to replace a previously uncharismatic manager may result in charismatic attributions at lower levels of the organization. New managers, trained in visioning and charismatic delivery style, might harness this advantageous situation to increase charismatic attributions and support from their

345

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

1(3) Articles

subordinates. Perhaps it is at this level where the power of charismatic leadership is most underutilized and understudied. However, it is important not to over-emphasize the potential generalizability of charismatic attributions in the US political process to everyday workplace dynamics, and ndings from this preliminary study should be interpreted with caution. This study examined the views of voters rather than employees, and business leaders are typically appointed rather than elected by popular vote. These differences may create certain difculties when seeking to transfer our arguments to other contexts; however, the increasing visibility of corporate executives necessitates leaders who are as interpersonally effective, adept at communications, and politically skilled as their counterparts running for public ofce, warranting some crossover between the two realms (Kellerman, 2003). Voters political afliation and its possible relationship to perceptions of charisma is another important consideration when interpreting our results. Only 21 per cent of our sample stated that they were independent voters, suggesting that 79 per cent of the sample acknowledged some political preconceptions prior to rating the candidates. These followers were clearly not completely unbiased, and as a result may not be willing to ascribe charisma impartially or as the result of merit alone. Charisma is in the eye of the beholder, and it is likely that followers with a strong party afliation are more likely to develop a charismatic bond with a leader that they perceive embodies the values they hold dear. As such, identication with a leaders values, represented by party afliation in the current study, is likely to drive ratings of charisma and expected effectiveness, consistent with previous research (Pillai et al., 2003; Pillai & Williams, 1998). Although we controlled for party afliation in our analyses, future research might explore the consistency, robustness, and potential exceptions to this tendency. Specically, when are followers most susceptible to a charismatic leader whose political afliation or background is different from their own? How do followers resist the charismatic inuence of leaders outside of their political party? And, when comparing candidates within the same party, does charismatic content and delivery play an even greater role in attributions of charisma? Future research should also examine different levels and types of crises, in order to determine how crisis severity may inuence perceptions of charisma. It is likely that the greater the severity of the crisis, the more likely charismatic attributions will result. In addition, further research into the relationships among different types of crisis and charisma is warranted. Coombs and Holladay (2002) distinguish types of crises by personal control, or leaders ability to control the event, and crisis responsibility, or how much the leader is to blame for the event. These distinctions may be of critical importance in understanding how different types of crisis foster varying levels of charismatic attributions. For instance, a scal crisis that affects an individuals livelihood may trigger the need for a charismatic savior more readily than a public relations crisis engendered by an oil spill. As in many real-world studies, the current research is somewhat hindered by the fact that incumbency, party, and personality differences in the three candidates could never realistically be systematically varied or controlled. Although Schwarzenegger certainly qualies as a trained actor in the action hero genre, our leaders were not instructed to display elements of both high and low charismatic delivery styles in the political realm, nor were the speeches they gave manipulated to be high or low in

346

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership

The California Recall Election Bligh et al.

charismatic content. In addition, our use of follower ratings as the sole method of data collection may raise the possibility of common-method bias. However, we feel the situational realism afforded by our design more than compensates for these shortcomings. In addition, our study focused solely on charismatic delivery in inuencing charismatic attributions. Future research may benet from the dual examination of perceptions of content and delivery in real life situations, as well as a wider variety of charismatic leader behaviors. In a closing statement, delivery style is a comparatively richer source of information for assessing leaders, as followers are able to evaluate both verbal and non-verbal communication styles. On the other hand, over a longer time horizon the effects of charismatic content may be more dramatic, as followers are increasingly exposed to the leaders vision and can more accurately evaluate its importance and relevance. Future studies might have different groups of participants read, watch on video, and hear audio only of a variety of speeches to tease out the effects of content, delivery, and their interaction across both close and distant social situations. Overall, our ndings suggest that contextual elements play an important role in follower assessments of charismatic leadership and effectiveness. Despite varying levels of charisma across the three personalities, ratings of all three leaders were inuenced either directly or indirectly by the crisis situation in California. These results suggest that in the context of a fallen leader and an unsuccessful administration, followers are increasingly receptive to an incoming leadership hero who can ride in on the proverbial white horse (or perhaps Hummer in this case) and save the day. In the early stages of his administration, Schwarzenegger has been able to sustain enormous approval ratings and a bipartisan image as an upstart and a political outsider who circumvents the legislature by bringing issues directly to the voters (Barabak, 2005). It remains to be seen whether or not the new leader will continue to capitalize on this advantageous situation and his charismatic personality to effectively resolve the crisis. Regardless of the outcome, charismatic leadership researchers should continue to explore the complex interrelationships among leaders, followers, and the situation in jointly determining the charismatic leadership relationship.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (eds) (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. Antonakis, J., Avolio, B. A., & Sivasubramaniam, N. (2003) Context and Leadership: An Examination of the Nine-factor Full-range Leadership Theory Using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, The Leadership Quarterly 14(3): 26195. Atkinson, J. M. (1984) Our Masters Voices: The Language and Body Language of Politics. London: Methuen. Atwater, L. E., Camobreco, J. F., Dionne, S. D., & Avolio, B. J. (1997) Effects of Rewards and Punishments on Leader Charisma, Leader Effectiveness and Follower Reactions, The Leadership Quarterly 8(2): 13352. Avolio, B. J., Waldman, D. A., & Einstein, W. O. (1988) Transformational Leadership in a Management Game Simulation, Group & Organization Studies 13: 5980. Awamleh, R., & Gardner, W. L. (1999) Perceptions of Leader Charisma and Effectiveness:

347

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on August 6, 2008 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Leadership