Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Anesthprog00226 0010

Încărcat de

carlina_the_bestDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Anesthprog00226 0010

Încărcat de

carlina_the_bestDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

SCIENTIFIC REPORT

Evaluation of Prilocaine for the Reduction of Pain Associated With Transmucosal Anesthetic Adminitstration

Louis F. Kramp, DMD,* Paul D. Eleazer, DDS, MS,t and James P. Scheetz, PhD*

*Private Practice, Redmond, Washington, tDepartment of Periodontics, Endodontics, and Dental Hygiene, University of Louisville,

Louisville, Kentucky, and tDepartment of Diagnosis and General Dentistry, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky

This investigation evaluated the use and efficacy of prilocaine HCI (4% plain Citanest) for minimizing pain associated with the intraoral administration of local anesthesia. Clinical anecdotes support the hypothesis that prilocaine without a vasoconstrictor reduces pain during injection. To determine relative injection discomfort, use of 4% plain prilocaine was compared with use of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine and 2% mepivacaine with 1:20,000 levonordefrin. Prior to routine endodontic procedures, 150 adult patients received 0.3 to 1.8 mL of local anesthetic via the same gauge needle without the use of a topical local anesthetic. Injection methods included buccal infiltration, labial infiltration, palatal infiltration, and inferior alveolar nerve block. Following each injection, patients were asked to describe the level of discomfort by scoring on a visual analog scale of 1 to 10, where I = painless and 10 = severe pain. Analyses via 2-way analysis of variance revealed no interaction between anesthetic and site of injection. However, there were statistically significant differences among the injection sites. Post hoc analysis revealed that prilocaine was associated with significantly less pain perception when compared to mepivacaine and lidocaine. These results suggest that differences in initial pain perception during transmucosal injection may be a function of the local anesthetic use, and prilocaine can produce less discomfort than the others tested. Key Words: Prilocaine; Transmucosal anesthetic administration.

M ost individuals exhibit some anxiety prior to the injection of local anesthetic before dental treatment. The clinical experience of one author (PDE) supports the hypothesis that use of prilocaine without a vasoconstrictor reduces pain during injection, and dental health care providers are interested in finding new agents for minimizing discomfort associated with anesthetic injections. It has been theorized that the use of an anesthetic with a pH that most closely approximates tissue pH (7.4) would be less irritating to submucosal tissues and therefore generate less discomfort upon injection. Typically, local anesthetics frequently include vaReceived April 4, 1999; accepted for publication July 16, 1999. Address correspondence to Dr. Paul Eleazer, Associate Professor and Director, Postgraduate Endodontics, and Interim Chair, Department of Periodontics, Endodontics, and Dental Hygiene, University of Louisville, 501 S. Preston Street, Louisville, KY 40292 Anesth Prog 46:52-55 1999 1999 by the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology

soconstrictors, such as epinephrine or levonordefrin, which require formulations in a lower pH environment to retain pharmacologic activity. The pH differential is believed to contribute to increased pain during injection. This hypothesis has been supported in previous invesfigations that evaluated pain perception during the injection of various anesthetics such as lidocaine, bupivacaine, and etidocaine. In these studies, pH was adjusted to lessen pain upon injection.1"2,3 According to the manufacturer, prilocaine used without a vasoconstrictor has a pH in the range of 6.0 to 7.0. Of interest in this research was a determination of whether prilocaine has any potential use for reducing patient discomfort during dental injection. For comparison, 2 other routinely used anesthetics, 2% mepivacaine with levonordefrin and 2% lidocaine with epinephrine, were used.

ISSN 0003-3006/99/$9.50 SSDI 0003-3006(99)

52

Anesth Prog 46:52-55 1999

Kramp et al 53

It

I I

I

I

4

5

I

7 8 9

10

Check along the above line (where I = no pain on injection, and 10 = severe sharp pain)

Figure 1. Visial analogue scale instrument.

METHODS

The 3 test anesthetics used in this study were obtained from a local dental supplier and included 2% mepivacaine HCl with 1:20,000 levonordefrin (Astra Pharmaceutical Products, Inc, Westborough, Mass), 2% lidocaine HCI with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Astra), and 4% prilocaine HCI without vasoconstrictor (Astra). Each anesthetic was batch-tested to assess pH using a pH meter (Beckman Scientific, Pittsburgh, Penn). All participants in the investigation were patients of the graduate endodontic clinic at the University of Louisville School of Dentistry in Louisville, Ky. After invitation to participate in and explanation of the procedure, each patient was presented an informed consent form for informational purposes and signature. Patients in severe pain or demonstrating regional lymphadenopathy, soft tissue edema, or infection were excluded to minimize effect of preexisting pain on injection pain perception. Furthermore, each patient was screened to eliminate any participant presenting a history of pertinent allergy, systemic disease, or potential drug interaction. One-hundred fifty consecutive consenting adult patients were treated. Anesthetic was selected by random draw from a box containing 50 cartridges of each anesthetic agent tested. The labels were carefully taped to obscure identifying characteristics. A window was left to allow visualization of intravascular aspiration. After reviewing the procedure with the patient, a single investigator (LFK) administered 0.3 to 0.6 mL of anesthetic for infiltration and 1.8 mL for inferior alveolar block. Topical anesthetic was not used to eliminate that potential variable. For consistency, 30-gauge needles were used throughout the study. Consistent injection speed was used, with the target rate of 1.8 mL per minute. No procedures were used in cases in which more than 1 tooth was to be treated. Transmucosal injection sites included (a) inferior alveolar (mandibular) nerve block, (b) buccal infiltration (maxillary or mandibular premolar or molar), (c) labial

infiltration (maxillary or mandibular incisor or canine), and (d) palatal infiltration (premolar or molar, 2 to 3 mm from gingival crest). Following the injection, each patient was asked to describe the level of discomfort associated with the injection by marking the appropriate number on a visual analog scale (shown in Figure 1).4 The investigator then recorded the anesthetic injected by removing the tape covering the label; the injection site location and volume of anesthetic used were also recorded. This blinding precluded equal numbers in each category. The data were analyzed via 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the NewmanKeuls procedure used for multiple comparisons.5

RESULTS

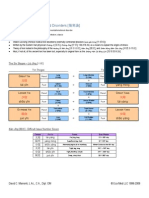

Tlhe means and 95% confidence interval ranges for each of the treatment combinations are shown in Table 1. The ANOVA results presented in Table 2 show no stafistically significant interaction between anesthetic and injection site. A statistically significant difference in pain perception exists between the 3 anesthetics, but overall there is no difference in pain perception for the 3 injection sites. The multiple comparison procedure shows that prilocaine resulted in less perceived pain when compared with mepivacaine and lidocaine. There was no statstically significant difference in pain perception when mepivacaine was compared with lidocaine. A compaison of pain perception for each anesthetic across injection sites shows that prilocaine resulted in less perceived pain than mepivacaine and lidocaine, with the exception of lidocaine at the labial infiltration site. These results are shown in Figure 2. Results of the pH tests were as follows: lidocaine = 4.12; mepivacaine = 3.05; prilocaine = 6.28.

DISCUSSION

Many patients requiring dental care experience fear and anxiety relating to the injection of local anesthetic.

54

Evaluation of Prilocaine

Anesth Prog 46:52-55 1999

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Anesthetics and Injection Sites Anesthesia Mandibular Block Buccal Infiltration Labial Infiltration Palatal Infiltration 2% mepivacaine with N = 12 N = 14 N = 12 N = 12 levonordefrin M = 3.00 M = 2.75 M = 4.00 M = 2.75 CI = 2.14-3.86 CI = 1.81-3.69 CI = 2.32-5.68 CI = 1.85-3.65 Lidocaine 2% with N = 13 N = 12 N = 13 N = 12 epinephrine M = 2.61 M = 3.08 M = 2.31 M = 3.50 CI = 1.67-3.56 CI = 1.83-4.34 CI = 1.41-3.21 CI = 2.21-4.79 Prilocaine (plain) N= 11 N = 11 N = 17 N = 11 M= 2.00 M= 1.36 M= 2.65 M= 2.27 CI = 1.00-3.00 CI = 1.02-1.70 CI = 1.88-3.42 CI = 1.37-3.18 Column mean N = 36 N = 35 N = 44 N = 35 M= 2.56 M= 2.43 M= 2.98 M= 2.86 Abbreviations: N, number of observations; M, mean pain perception score; CI, 95% confidence interval.

Row Mean N = 50 M = 3.16

N = 50 M = 2.86 N = 50 M= 2.14

Therefore, it behooves the dental health care provider to make an effort to minimize the adverse impact of this procedure. Investigations into the relationship between needle type and pain perception upon injection have not shown any difference between 25- and 30-gauge needle use.6 Empirical reports refute any relationship between anesthetic temperature and pain perception.7 Animal studies have shown that both temperature and pH do affect muscular contraction and nerve repolarization properties.89 This experiment suggests that prilocaine injections are associated with less pain perception. This may be due to

the more neutral pH of prilocaine when compared with other commonly used anesthetic preparations. The overall low rankings of pain scores may be due to the greater stoicism of a population of dental school patients. If a private sector patient population had been studied, the range of results may have been wider. Another factor is that a relatively slow injection speed was used, a recommendation many clinicians admit to ignoring.7 There are some cautions regarding prilocaine. One past study demonstrated that prilocaine is associated with higher fibroblast toxicity in tissue culture.10 Furthermore, a dose-dependent condition, methemoglobinemia, can occur with prilocaine.7 Haas and Lennon searched malpractice records of all dentists in Ontario and found nerve damage from local

anesthetics in 143 cases where no surgery was performed. They estimated the rate of nerve damage at 1 per 785,000 cases. Articaine was most frequently indicted (33.6% of the reports), with prilocaine second (28.9% of the cases in which the agent was known). Lidocaine was responsible for dysesthesia in 3.4% of the legal actions. The lingual nerve was the site of damage in 92 of the 143 incidents, contrasted with 42 incidents of lip pain or numbness and 9 incidents with both lip and tongue involved. They found no cases of maxillary dysesthesia and suggest mild neurotoxicity of the solution as the most likely cause.1" In a related article, they estimated that 16.4% of practitioners in the study area used prilocaine with vasoconstrictor, and 3.9% used plain prilocaine. They did not address the possibility of a difference

between these 2 formulations relative to nerve damage.'2 Pogrel et al studied 12 patients referred to a university

center over a 4-year period for dysesthesia following lo-

cal anesthetic for nonsurgical procedures. Three of these patients received prilocaine with vasoconstrictor, and 8 patients were treated with lidocaine with vasoconstrictor. 3

Although there is conjecture about the clinical significance of past studies as well as this one, the judicious use of prilocaine may nevertheless be of value in the apprehensive patient or with use at specific sites known for painful injections. Clearly, the selection and use of

Table 2. Two-Way Analysis of Variance Comparing Anesthetic and Injection Site Source of Sum of Degrees of Variation Squares Freedom Mean Square F Value F PROB Anesthetic 29.649 2 14.824 5.129 0.007a Injection site 8.315 3 2.772 0.959 0.414 (NS) Anesthetic by injection site 26.841 6 4.473 1.548 0.167 (NS) Error 398.872 138 2.890 Total 463.497 149 Abbreviation: NS, not significant. a p < 0.01.

Anesth Prog 46:52-55 1999

Kramp et al

55

REFERENCES

4.5,

T

!

j

1

T

3.53- { i

1|1 Mepivacaine Lidocaine * Prilocaine

0~~~~~

1.50.5-

0~~~~~

Figure 2. Comparison of pain perception VAS scores and injection site. any local anesthetic should be made with consideration to many factors, such as desired duration of action, site of injection, required volume, anesthetic toxicity, potential cardiovascular effects, concurrent systemic diseases, and drug therapies. This pilot study has demonstrated that the use of anesthetic preparations that approximate tissue pH may be accompanied by less injection discomfort.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to express appreciation to Dr. Earl Walker for assistance in data collection and to Dr. Peter Fotos for consulting and manuscript preparation.

1. Cheney PR, Molzen G, Tandberg D. The effect of pH buffering on reducing the pain associated with subcutaneous infiltration of bupivicaine. AM J Emerg Med. 1991;9:147-148. 2. Farley J, Hustead R, Becker K. Diluting lidocaine and mepivacaine in balanced salt solution reduces the pain of intradermal injection. Reg Anesth. 1994; 19:48-51. 3. Howe NR, Wilhams JM. Pain of injection and duration of anesthesia for intradermal infiltration of lidocaine, bupivacalne, and etidocaine. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:459-464. 4. McGrath PA. The measurement of human pain. Endodont Dent Tranmatol. 1986;2:124-129. 5. Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1999. 6. Fuller NP, Menke RA, Meyers WJ. Perception of pain to 3 different intraoral penetrations of needles. JADA. 1979; 99:822-824. 7. Malamed SF. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1990. 8. Foulks JG, Perry FA. The effects of temperature, local anesthetics, pH, divalent cations, and group-specific reagents on repriming- and repolarization-induced contractures in frog skeletal muscle. Canad J Physiol Pharmscol. 1979;57:619-630. 9. Schwarz W, Palade PT, Hille B. Local anesthetics, effect on pH on use-dependent block of sodium channels in frog muscle. Biophys J. 1977;20:343-367. 10. Johnson RB, Dowse CM. Comparative effects of local anesthetic preparations on gingival fibroblasts of the rat. J Dent Res. 1986;65(9):1125-1132. 11. Haas DA, Lennon D. A 21-year retrospective study of reports of paresthesia following local anesthetic administration. J Canad Dent Assoc. 1995;61(4):321-330. 12. Haas DA, Lennon D. Local anesthetic use by dentists in Ontario. J Canad Dent Assoc. 1995;61(4):297-304. 13. Pogrel MA, Bryan J, Regezi J. Nerve damage associated with inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996; 126:1150-1155.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- SchizophreniaDocument67 paginiSchizophreniaHazirah Mokhtar100% (1)

- 83 Nutripuncture OverviewDocument12 pagini83 Nutripuncture OverviewTimoteo Pereira TfmpÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Pediatrics PDFDocument208 paginiThe Little Book of Pediatrics PDFPaulo GouveiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Páginas Desdepharmacotherapy Casebook 10th Ed.Document61 paginiPáginas Desdepharmacotherapy Casebook 10th Ed.Glo VsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence Based Assessment of OCDDocument17 paginiEvidence Based Assessment of OCDDanitza YhovannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Intensive Care UnitDocument120 paginiMedical Intensive Care Unithaaronminalang100% (6)

- Nursing 110 FinalDocument36 paginiNursing 110 FinalAngel Lopez100% (1)

- Case Study Severe Depression With Psychosis.: Submitted To:-Submitted ByDocument33 paginiCase Study Severe Depression With Psychosis.: Submitted To:-Submitted ByPallavi KharadeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment On DislysisDocument10 paginiAssignment On DislysisSanhati Ghosh Banerjee100% (1)

- 傷寒論 Shang Han LunDocument3 pagini傷寒論 Shang Han LunDave Mainenti97% (30)

- Impacted Canines-Ericson & KurolDocument13 paginiImpacted Canines-Ericson & Kurolcarlina_the_best100% (2)

- Cellular, Molecular, and Tissue-Level Reactions To Orthodontic ForceDocument32 paginiCellular, Molecular, and Tissue-Level Reactions To Orthodontic Forcecarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compression Fibroblasts PDLDocument9 paginiCompression Fibroblasts PDLcarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articulo ForsusDocument7 paginiArticulo Forsuscarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perception of Discomfort During Initial Orthodontic Tooth AlignmentDocument6 paginiPerception of Discomfort During Initial Orthodontic Tooth Alignmentcarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Givcen: in in The Factors inDocument9 paginiGivcen: in in The Factors incarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Briefly: PointsDocument3 paginiBriefly: Pointscarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jop 2012Document9 paginiJop 2012carlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The CareDocument5 paginiDental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The Carecarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jop 2012Document9 paginiJop 2012carlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intracellular Comunication Ii: Aloa Lamarca DamsDocument31 paginiIntracellular Comunication Ii: Aloa Lamarca Damscarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abrir o Cerrar 1kjokich-Missing Laterals-Part IDocument6 paginiAbrir o Cerrar 1kjokich-Missing Laterals-Part Icarlina_the_bestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis - WikipediaDocument32 paginiDiabetic Ketoacidosis - WikipediaSanket TelangÎncă nu există evaluări

- सञ्चयकर्ता स्वास्थ्योपचार योजना सञ्चालन कार्यविधि, २०७७-50e1Document13 paginiसञ्चयकर्ता स्वास्थ्योपचार योजना सञ्चालन कार्यविधि, २०७७-50e1crystalconsultancy22Încă nu există evaluări

- Ginjal Polikistik PDFDocument15 paginiGinjal Polikistik PDFAgunkRestuMaulanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MPC-CPN Basics of Toxicology-HDocument12 paginiMPC-CPN Basics of Toxicology-HNahid ParveenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preeclampsia Pathophysiology andDocument15 paginiPreeclampsia Pathophysiology andYojhaida Zarate CasachahuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secondary Amenorrhea Therapy With Accupu 2c484cf6Document5 paginiSecondary Amenorrhea Therapy With Accupu 2c484cf6NurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rog Final MDDocument5 paginiRog Final MDSaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aparat Elect Rot Era Pie Aries MDocument2 paginiAparat Elect Rot Era Pie Aries MSorin NechiforÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Basic Medical Unit in Our Country Is A PolyclinicDocument3 paginiThe Basic Medical Unit in Our Country Is A PolyclinicLykas HafterÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5,600 Residents Tested: Case SummaryDocument3 pagini5,600 Residents Tested: Case SummaryPeterborough ExaminerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3f - 1 (Division of Task)Document33 pagini3f - 1 (Division of Task)Trisha ArtosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ultrasonic Surgical & Electrosurgical System: All in One Pla Orm, All With Superior PerformanceDocument2 paginiUltrasonic Surgical & Electrosurgical System: All in One Pla Orm, All With Superior PerformanceDiego DulcamareÎncă nu există evaluări

- MEdication ErrorsDocument6 paginiMEdication ErrorsBeaCeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- MenopauseDocument19 paginiMenopauseMuhammad AsmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- SBARDocument2 paginiSBARNabiela Aswaty 2011125083Încă nu există evaluări

- Patient Record BookDocument1 paginăPatient Record BooksumarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health and Hindu Psicology by Swami AkhilanandaDocument245 paginiMental Health and Hindu Psicology by Swami Akhilanandaapi-19985927100% (3)

- NCP EsrdDocument9 paginiNCP EsrdMarisol Dizon100% (1)

- 32 PDFDocument22 pagini32 PDFniallvvÎncă nu există evaluări

- DosulepinDocument4 paginiDosulepinbrickettÎncă nu există evaluări