Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

04 Homer On Virtue

Încărcat de

Dr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

04 Homer On Virtue

Încărcat de

Dr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

4.

An Overview 4-1

4.

4.1

4.1.1

HOMER ON VIRTUE AND COSMOLOGY

An Overview

SETTING THE SCENE

MASTER SAPIENS Let us start this first Philosophical debate by asking Whiz Dom to translate from Italian the passage in Cioffi et al I:39-401 that I find is a great introduction to Homer. W HIZ-DOM The Homeric poems give us a picture of the Greek society at its origins and its morality. The values of the warriors, chieftains of the aristocratic clans (ghe ne) are the prevalent values portrayed. Land is concentrated in the hands of these warriors, as is political and military power. In this epoch (archaic Greece), virtue (arete ) is identified with strength. Social prestige is confined to the ability of lording it over others using violence (bie): one can keep one place among the select group of aristoi (the betters) because one has s the power to impose one will on a herd of inferior weaklings. s Since one virtue is bound to the imposition of might, in the Iliad, the virtue of the hero s is not a stable acquisition, but must be shown in action whenever it is questioned. Subjecting oneself to the will of another is unacceptable to one virtue: this constitutes a s dishonour that can only be removed by, in turn, imposing one will on the offender. s Achilles, offended by Agamemnon who took Briseis away from him, thinks that there is no other way to regain his arete but through the use of violence: he renounces a fight with the supreme chief of the Achaean army only because Athena orders him to do so. He retires from war vexed and dishonoured: the Greeks have to accept that without the arete of Achilles they are not able to win over the Trojans and to regain for Achilles the honour of which Agamemnon deprived him. The Odyssey system of values is more complex. New motifs appear, linked to the time s of peace in which they second Homeric poem is set: namely family values and values linked to the good management of one property (oikonomia). Even the heroic arete s becomes more complexly characterised as the Odysseus of the Odyssey takes the place of the Achilles of the Iliad as the prime hero. The warrior might still constitutes s the core of arete (demonstrated, namely, in the violent justice dealt to the bad administrators of his property on his return to Ithaca) but this is supplemented with cunning (metis), intelligence (nous) and the ability of engaging persuasively in discourse (logos). These capacities allow the hero to prevail where the hero might is useless or insuffis cient (e.g. when Odysseus and his companions need to escape the Cyclops Polyphemus). MASTER SAPIENS What have you understood, Claire? MEN CLARA S O.K. We talking about Homer idea of virtue, aka re s goodness It must be different . from ours, otherwise, why bother? Nevertheless, I still don get what Cioffi is talking t about because I don know who these guys are and what they do in the story. Any t ideas, anyone?

1

Cioffi, Luppi, Vigorelli, Zanette. 2000. Il testo filosofico. Edizioni Scolastiche Bruno Mondadori. Milano. Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM

4-2

4.1

An Overview

THINK TANK The Iliad is the story of the siege of Troy during the Trojan War. Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek army (attacking the Trojans) offends the most skilful Greek warrior, Achilles, by taking his slave girl, Briseis. Achilles then refuses to fight with Agamemnon, and the Greeks start losing. The Trojans attack and kill Patroclus, Achilles friend, whom Achilles was expected to protect. To avenge his friend, Achilles returns to the battle (knowing he would be killed) and the Greeks win. In heaven, or better on Mount Olympus, the gods take sides, and intervene to help or hinder the heroes. The Odyssey gives us an image of the Greek hero in a time of peace: this time, it is a guy called Odysseus going back home from the Trojan war. He desperately wants to go back because his kingdom awaits him and is badly governed in his absence, but the gods try to hinder his return. MASTER SAPIENS All right. Let us take an hour by ourselves to read a page-long summary of the plot of the Iliad and the Odyssey from an encyclopaedia, or from the Web. Then, go back to the passage that Whiz-Dom read, and see if it makes more sense.

4.1.2

Tank Men s

S WHAT THE POINT?

Nobody thinks Homer was a Philosopher, right? So what the point in starting Philosos phy from Homer? Well, as Cioffi says, Homer gives us a picture of the Archaic Greek society what people in Greece thought about all sorts of things in life before the advent of Philosophy. Now I can think of two ways how this could be interesting to us studying Philosophy. A new idea does not come from nowhere. In a way, it CHALLENGES the old, i.e. the prevalent idea that preceded it. But in a way, it BUILDS ON THE OLD it assumes at least part of the context which sustained the old idea. Think of a proposal of changing, say, a bus route. Its defenders must contrast it with the old route and argue that it deals with the shortcomings of the old route this part of the argument will focus on the differences. However, they must also show how it serves the purposes of the old route, and how it links to the remainder of the bus network that will remain unchanged with the new route. This would focus on the similarities. Similarly, if a Philosopher has to stand up and say something new, he must be fully aware of the background of his/her listeners (which happens to be his/her very background). In Ancient Greece, this background was the Archaic Greek culture, which Homer simply portrays in his poems. If a Philosopher had to come up with a new way of defining what is the good thing to do in a given situation, he/she must CHALLENGE Homer (i.e. the Archaic culture) on that specific point but on the other hand he/she CANNOT BUT ASSUME some of that culture, otherwise his/her arguments would hang in the air, and nobody would understand him/her. You cannot change a system of thought all in one big swoop. I think a famous metaphor for what you are saying, Men is that of the raft. You can s, mend a raft at sea, but by replacing one log at a time. If you try to mend it all at once, it will sink. Similarly, if the Ancient Philosophers wanted to remedy for the shortcomings of the Archaic culture portrayed in Homer (as regards Moral thinking, Cosmology, Theology), they could only challenge one thing at a time, otherwise their ideas would seem totally alien to their listeners (and to themselves for who could imagine a world totally different from the one she was taught to believe in since she was a child?). So they would use bits of Homer to sustain some of their arguments that in turn would challenge other parts of Homer.

Whiz

Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM

4.2

An annotated summary of Irwin (1998), Chap. 2 4-3

Sap.

I must stop this discussion for some re-focussing. You are discussing some very interesting issues in Epistemology, but this is going too far. What is important at this point is that Homer is important to the Philosophers as the eloquent representative of the Archaic culture. Knowledge of this culture helps to define Philosophy positively, by pointing out similarities (comparison) and negatively, but pointing out differences (contrast). It helps us understand why the Philosophers said certain things that seem very strange to us, people who come from a very different culture. Now Whiz mentioned ETHICS (Moral Theory: the study of the principles that determine what is the right and the wrong thing to do, the study of the correct behaviour to assume in society), COSMOLOGY (the study of the structure of the Universe (= the sum of all existing things), its regularities, its origin and composition ), THEOLOGY (the study of the supernatural, and specifically of God/the gods). Homer never wrote a treatise on these subjects. But if you read through his poetic narratives, you can filter out a lot of stuff on what people in Archaic Greece thought about such issues. What is the good (virtuous) behaviour for the Homeric heroes? what is the right thing to do in certain circumstances? By observing the actions of Achilles and Odysseus and their consequences in the two works, we get interesting answers to these Ethical questions. How do natural forces work? How do the gods act? Again, read through Homer, and you will find how the Archaic Greek people would have answered such Cosmological and Theological questions. Incidentally, this procedure is the one used by Irwin in Chap. 2 of his book Classical ThoughtHe goes through the Iliad (mainly) and sees how the Greeks before the advent . of Philosophy answered these questions. In a way, though nobody would call Homer a Philosopher, Irwin analysis helps us to filter out some of the Philosophical elements s present in the Greek culture BEFORE what is officially considered as Philosophy came to be. It would be wrong to think that Philosophy came from nowhere. It came from a culture predisposed to ask certain questions. Such a predisposition constitutes the groundwork of Philosophy. After all, a lot of ancient non-western Philosophy is done by a similar analysis of ancient literary texts similar to Homer poems. s Tank, maybe you could give us a summary of Irwin and add some comments. This will help our non-initiated companions learn how to read a textbook, take notes, and reflect on it. I know your comments are often illuminating but sometimes quite tough for the beginners, Tank. But that O.K., they give us a taste of some of the s real issues, even hot if they may be hard to grasp.

4.2

An annotated summary of Irwin (1998), Chap. 2

Summary of Irwin (1998) Comments Some experts claim that Homer was not a historical person. Most agree that if anything, the name Homer designates a person who collected, compiled and edited a series of poems and stories of very ancient tradition. He moulded and elaborated these popular myths and stories around a clear central plot, using a popular poetic metre (the hexameter). Eventually, the whole compilations were learnt by heart and passed on by generations of poets till someone wrote them down.

i. The importance Iliad and Odyssey: of Homer

religious, cultural texts of great importance

did not have the doctrinal authority of the Hebrew Bible, yet were extremely influential over a wide area for hundreds of years, especially as a basic educational text.

philosophers often refer to the Homeric poems as the cultural 'given': at times as an authority to sustain their theories, at times as a target which is challenged and critiqued Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM by their theories.

4-4

4.2

An annotated summary of Irwin (1998), Chap. 2

their theories, at times as a target which is challenged and critiqued by their theories.

The plot indicates the existence a single editor, however, in itself, it is of secondary importance: the poems are best considered as a treasury from which we can reconstruct early Greek culture, language, religion, cosmology (rational explanation of the world), customs, morality and values, social structure, politics etc. Arete originally meant nobility ('good blood'); then was used to express excellence (at doing something, e.g. in combat); then came to mean virtue (maturity in a set of behaviours that a society/individual values because they help the society/individual achieve the goods that the society/individual aims at achieving); finally coming to signify moral 'goodness'. Arete is a social measure of goodness: it is goodness that others can see. We moderns often assume that true 'goodness' is something internal (good intention) that may not always translate into actions that are externally conceived as good and laudable, and that people who look saintly to the beholder may be rotten inside. The ancients did not share our scepticism on moral perception, possibly because social relationships were more defined, simpler and more authentic. They believed that a good person will be socially recognised as such, and hence be honoured as such. This is why arete and time (honour) are closely linked. The Homeric hero not only wanted to seem good in the eyes of others (and hence have their esteem); he also wanted to be good: he believed that (except in strange circumstances) one would seem good only if one were really good, and one who were good would seem good. Irwin calls the Homeric hero 'individualistic' since he seeks his honour first, but then Irwin claims that time is also 'otherdirected' since society may also blackmail the hero: "you can enjoy a good reputation (and hence serve your interest) only if you do x and y... which are things that serve our interest". I think this is a blatantly modern reading of the poems (see the discussion below).

ii. The ideal person and the ideal life

The poems' heroes are ideal persons who exemplify arete (= goodness, excellence, virtue). This is not identical to the Christian or to the Modern (e.g. Kantian) concept of goodness, hence may sound strange to us. 1. arete (goodness that others can see) is PARTLY OUTSIDE OUR CONTROL. Clearly, propriety and virtue in our public behaviour are influenced by the circumstances in which we were born and grew up. This is traditionally expressed by the idea of 'noble blood' and often treated as a hereditary component of arete . A person who grew up in socially unfavourable circumstances cannot be expected to excel (publicly)... especially in the strongly stratified archaic Greek society where the moral achievements of the lower classes were disregarded. (The upper class at the time, the 'nobles', was that of the warriors; hence excellence was in the first place military prowess). 2. arete is PARTIALLY IN OUR CONTROL. Given the right social/hereditary conditions, it is our job to excel. Public excellence generates personal honour (time ), that includes primarily other people's good opinion, and secondarily the material and social 'honours' linked to the former. Heroes seek to increase their success and reputation, and hence seek to perform acts of excellence, which not only benefit the hero but also the persons from whom the hero seeks respect.

iii. Self and Others

Homeric goodness (arete ) is linked to the way one treats others, but this is not the major component of arete . Hence, one may treat others badly and still be considered good and virtuous .

Homeric goodness is not primarily the goodness shown towards others. The word goodin Homer designates someone who stands out from the crowd because s/he is better than the rest: richer, more powerful, stronger, imposingly superiori.e., a person who, in virtue of his/her , social standing and his/her achievements Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM can demand respect and reverence from the others. Achilles (in The Iliad) and Odysseus (in The Odyssey) are depictions of such a super-man .

4.2

An annotated summary of Irwin (1998), Chap. 2 4-5

A hero is expected 1. to care for his inferiors (e.g. wife, children, subjects ); 2. to care for the welfare of his group of peers (e.g. comrades in the army, co-citizens); 3. to be moved by human feelings (and not be indifferent towards others, their problems, their suffering, their honour ). If a hero fails to do these things he is criticized, but does not substantially lose his arete . Achilles remains the best of the Achaens even if he abandons the army on a personal matter (thereby letting down his peers and letting down his inferior, Patroclus by not fighting by his side and protecting his life). On the other hand, had Achilles been captured by pirates and sold into slavery, he would have lost half his virtue/goodness.

more powerful, stronger, imposingly superiori.e., a person who, in virtue of his/her , social standing and his/her achievements can demand respect and reverence from the others. Achilles (in The Iliad) and Odysseus (in The Odyssey) are depictions of such a super-man .

For primary virtueshere are those viriv. Priorities a Homeric hero [ ] the interests of The other people are often important, but always strictly secondary. Indeed they count for so much less than the primary virtues that a man goodness or bads ness is finally measured by the primary virtues alone, not at all by his concern for others. (Irwin, 1998:11.)

tues that directly promote one honour s and good reputation: leadership, physical might, social standing, skill at managing one s household, political farsightedness

v. Difficulties in Homeric ethics

The Homeric hero seeks to accomplish his own aims in life, which he considers the best for himself. But Homeric morality also asks him to behave in such a way so as to merit honour and esteem from his peers, and claims that such behaviour is the best behaviour. This may create conflicts within the hero between what he considers best himfor self and what others consider best for him.

Irwin (like most Anglo-American philosos phers) is influenced by a Modern author, David Hume, and his reading assumes that the good in Homer is subjectivei.e. : actions and things are not good or bad in themselves but whether something is good or bad depends ultimately on who is JUDGING. To abandon the battle because one honour is offended may thus be the s good thing to do for Achilles, but may be considered bad by his companions.

I believe this is a bad way of reading Homer, since all ancient and traditional morality assumes moral objectivity (i.e. it is non-subjective): it assumes that something is good or bad independent of who is judging it. Hence, if there is any conflict on what is the good thing to do, or the best thing to do, it is because the hero or those around him have not yet DISCOVERED what is good, or what is the best thing to do in those circumstances. In Archaic society, one assumed that what was socially esteemed was so esteemed BECAUSE it was objectively good the basis of a vener(on able social tradition that was considered Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM knowledgeable of what was good), and NOT that something was good BECAUSE it was socially esteemed as desirable. Within this objectivist framework, Irwin s critique does not make any sense. The conflicts within the Homeric hero are nor-

4-6

4.2

An annotated summary of Irwin (1998), Chap. 2

teemed was so esteemed BECAUSE it was objectively good the basis of a vener(on able social tradition that was considered knowledgeable of what was good), and NOT that something was good BECAUSE it was socially esteemed as desirable. Within this objectivist framework, Irwin s critique does not make any sense. The conflicts within the Homeric hero are normal everyday moral problems of a mortal who does not know everything in advance, but needs to discover what is objectively good for him/her day by day. Furthermore, the selfish and parasitic behaviourof the Homeric heroes is bad for the whole community, and yet, from one point of view, it is eminently heroic This seems to be an incoher. ence in Homer ethics. s The problem, here, is only Irwin not s, Homer The behaviour of the Homeric s. heroes is the paradigm, the model, of what Homer considers goodwith all the com, plexities involved in that conception. Such behaviour is simply eminently heroicfor Homer; if it is selfish and parasitic (from Irwin point of view, or even objectively) it s certainly does not appear so from Homer s standpoint. Hence, contrary to what Irwin claims, Homer ethics does not seem INs TERNALLY incoherent. I think that no serious defender of Homeric morality would use an argument based on the UTILITY of the social structure that generates Archaic morality to defend such a morality. What is GOOD cannot be reduced to what is USEFUL, and this is more so in traditional ethics, such as that of Homer. Killing someone who is harming a lot of people may be useful to those people, but may not necessarily be a good thing to do. Building a dam may be very useful, but it may be a bad thing to do if it entails provoking an ecological disaster. A defender of Homer cannot claim that the social inequalities in Homer are good because they are useful. He or she may simply claim that people are not born equal (this is a claim that can neither be DECISIVELY proved, nor disproved), and that trying to put the betters on the same level as the inferiors is contrary to the order of nature and to the desire of the gods (or of God). Obviously, we would not find this acceptable today (because of our social and ethical background), but surely, most Archaic Greeks did. And Nietzsche, and the Fascists, who held similar views, are still very contemporary!

Irwin then provides a hypothetical argument of a defender of Homeric morality who claims that in the conditions of an Archaic society, the Homeric hero might be useful to his community. This would be the reason why society should be structured in such a way. Irwin claims that this is a weak defence of Homeric morality.

vi. Gods and the Homer depicts the gods using human A predictable universe is one which hus, world forms (rather than monstrous images) mans can control. In the 1600 scientists

because he wants to make them intelli- like Descartes and Newton produced degible: fairly rational agents with fairly terministic models of the universe that stable aims are predictable and reli- tend to present reality as totally predictable On one Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM promoted the idea that humans . hand gods are not sim- able. This ple, rigid mechanisms: you offer this can, with the use of machines, have full sacrifice, they give you that. They care control over nature. People started to befor sacrifices but do not let themselves lieve that science and technology would be manipulated through them. On the eventually solve all our problems, take us other hand, they are not too complex to wherever we want, kill pests, overcome understand and to deal with. Knowing disease and death. Einstein model has s

4.2

An annotated summary of Irwin (1998), Chap. 2 4-7

gible: fairly rational agents with fairly stable aims are predictable and reliable On one hand gods are not sim. ple, rigid mechanisms: you offer this sacrifice, they give you that. They care for sacrifices but do not let themselves be manipulated through them. On the other hand, they are not too complex to understand and to deal with. Knowing what the gods are after, persons can tell more or less how they will behave. Natural forces, similarly, do not strike at random, but as a result of the steady purposes and intentions of the gods(p . 14). Hence, in the Homeric universe, MOST THINGS HAPPEN FOR A REASON. This conception of the world eventually leads to a search for regularities and laws in nature, which flourishes into scientific disciplines and philosophy. Even so,

THERE IS ALSO SPACE FOR CHANCE EVENTS in the Homeric universe.

terministic models of the universe that tend to present reality as totally predictable. This promoted the idea that humans can, with the use of machines, have full control over nature. People started to believe that science and technology would eventually solve all our problems, take us wherever we want, kill pests, overcome disease and death. Einstein model has s reintroduced a lot of chance and unpredictability in the universe. Today, we are more sceptical of what power technology can give us over nature, and at what cost.

vii. Gods and moral In the poems, Gods are the ultimate paradigms heroes ); ideals moral ideals (or

exemplify virtue because they strive to act like the gods. The gods, on the whole, are content with their eternal lives. They do get angry at times, but they usually get satisfaction in such cases. They possess security, life, honour, power. Heroes, however, are mortals, and cannot get it all as the gods do. In order to be secure like the gods, they often have to forsake honour. To attain godly power, they risk losing their security, or their life. Hence they must often face conflicts among their aims.

viii. Zeus and the Zeus is above all the other Gods, and Zeus and the Fates are portrayed anthroin world order Homer insists that HIS WILL IS IN CON- pomorphically in Homer (i.e. the shape

TROL.

So what prevails, Order or Disorder? Who has the last word, Zeus or the Fates? Homer does not give us a satisfactory anIrwin suggests that this relationship be- swer (and this paves the way for the detween Zeus and the fates indicates two velopment of Philosophical cosmology). trends in Homeric thinking that are po- He insists that Zeus (Order) is supreme. tentially in opposition: fates suggest This means that the universe has an orthe Rene Mario order, inde- der, AM an impersonal, amoral Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 it is regular and predictable (and pendent of the choices of gods or hu- hence can be studied scientifically we man beingswhile Zeus suggests a can make generalizations and laws on moral order embodying an intelligence how things behave in the universe). This and will that transcend normal heroic tendency (to assume Order as supreme) values, but still recognizably belong to is prevalent in Greek culture, and it drives an intelligent moral agent. 17) (p. the first scientific enquiries. Yet Homer

He seems to have wider concerns than his own honour and also is concerned with justice in human societies(p. 17). Nonetheless, he has a strange relation with the fates Time . and again, he seems able to save a particular hero from his fate (that decides whether he has to die or not in a given occasion), and ponders on whether to do so or not, but in the end, his decision always turns out to conform to the fates.

of human beings but in a Cosmological ), reading of the poems they personify the forces of Order and Disorder present in the Universe. This means that when we ask the question what does Homer think about the regularity an the irregularity ( kaos in the universe? the answer can ) , be found in his stories that put Zeus face to face with the fates.

4-8

4.2

An annotated summary of Irwin (1998), Chap. 2

trends in Homeric thinking that are potentially in opposition: fates suggest the an impersonal, amoral order, independent of the choices of gods or human beingswhile Zeus suggests a moral order embodying an intelligence and will that transcend normal heroic values, but still recognizably belong to an intelligent moral agent. 17) (p.

He insists that Zeus (Order) is supreme. This means that the universe has an order, it is regular and predictable (and hence can be studied scientifically we can make generalizations and laws on how things behave in the universe). This tendency (to assume Order as supreme) is prevalent in Greek culture, and it drives the first scientific enquiries. Yet Homer never gives us an example of real conflict between Zeus and the Fates. He shuns the issue, and is reluctant to conclude that Zeus would prevail. So Zeus is portrayed always as coming to a decision independently, which happens to confirm that of the fates. At the bottom of all this lies a very important question. In science, we assume an order in the universe. Is this real or simply apparent? We are aware of the presence of both order and disorder in the universe. Is the disorder only apparent, i.e. a complex combination of regular elements? Or is the order only apparent (a chance regularity in a sea of disorder)?

ix. The main diffi- In Homer we find an ETHICS (a discusculties in Homer sion on what is the best thing to do,

what is the goodin relationships between human beings, between humans and gods, between humans and nature), a THEOLOGY (a discussion about who the gods are, how they behave ) and a COSMOLOGY (a discussion about the world, nature, the universe: i.e. about the forces present in natural events, the regularities in nature (corresponding to the will of Zeus, who is more or less predictable), the unexplainable in nature (corresponding to the unpredictable, unintelligible Fates)). Homer Ethics, Theology and Cosmols ogy appeal to COMMON SENSE and to EVERYDAY EXPERIENCE (our observation of the world). Hence they are difficult to disprove, and resist critiques. Yet, the three disciplines abound with internal conflicts, and this spurs the first Philosophers to find new theories to determine what is the Good, who is God, how does the World work.

Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM

4.3

Are the Homeric Heroes selfish and individualistic ? 4-9

4.3

Are the Homeric Heroes selfish, and individualistic,?

Note: Men just pinched this bit from the sketches of a book on Ethics that Master Sapiens is s writing. It is rather tough stuff not for the faint-hearted. But do give it a try. It gives you an idea of some of reactions that a mature Philosopher may have when reading Irwin. If it seems too difficult, just move on. Are the Homeric heroes selfish and individualistic Irwin claims that they are, all over the chap? ter. Clearly, from our point of view as students in a democratic, developed country, they seem so. But I think that the words selfish and individualistic not appropriate to describe the Homeric are heroes.

4.3.1

AN ANALYSIS OF WHAT WE CONSIDER

SELFISHAND INDIVIDUALISTICIN ORDINARY LANGUAGE SHOWS THAT WE CANNOT ATTRIBUTE THESE TERMS TO THE HOMERIC HEROES

Consider the following examples: Tom is a person who is already very rich and who seeks to become ever richer (and other people are influenced negatively by this, since resources are limited). We call Tom selfish. Jane is an athlete who seeks to break the world record for the 1000m race. She is ready to sacrifice many things for this. Unless she gravely neglects very important duties in order to achieve his goal (e.g. abandoning her husband and children) we would not call her selfish in this. Peter is a good footballer who very rarely passes the ball when he is in a position to score even if there is a team-mate in a better position. We would call this behaviour selfish only if it is detrimental to the team in the long run. Alice, a tourist visiting a developing country, finds herself in a jungle where a number of natives are about to be executed for no good reason. She protests to the authorities, who answer that if she wants to free the natives, she should offer up her life in their stead. If she refuses to do so, we would not call her selfish because she has no duty to give up her life for the sake of the natives.

Thus, we call selfish person who seeks to profit himself/herself at the expense of others, who a is ready to let down the team or take over other people fair share of the resources of society in s order to advance his interest (e.g. Peter and Tom). Seeking to advance one interest when this s does not influence others is not selfish (e.g. Jane) it is rather a matter of respect for one s goals in life. What about seeking to advance one interest when this influences others? Well, it s depends. There are things in life that are so central to our being that we cannot sacrifice them (or cannot be expected to sacrifice them) for the sake of others. Alice LIFE is a good example. Cons sider, further, that instead of giving up her life, Alice is asked to shoot one of the natives herself, and the others would then be set free (if she does not, all will be killed). Alice RELIGION des mands that she does not kill (even if, overall, more people are killed (by others) as a result of this). She is certainly not selfish if she does not go against her religion to save a large number of people, since religion is so central to one life that it cannot easily be put aside (thereby commits ting, say, a grave ) for the sake of others. Some philosophers say that we are sin situated , encumbered selves. This means that there are SOME things we just cannot give up for the sake of others. In the case of the Homeric heroes, HONOUR was something that could not be given up, even at the expense of letting down the team and thence loosing a war. Hence, I find it hard to call Achil-

Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM

4-10

4.3

Are the Homeric Heroes selfish and individualistic ?

les selfish since honour was at the time the basis of morality and of authority. Furthermore, each hero represented a clan, a people, hence his honour was that of the kingdom came from. he The Trojan War was sparked by a personal affair the elopement of Helen with a lover from a different nation. Such a personal matter is considered an offence to the whole nation, not only to her husband. Similarly, the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon is not simply a dispute between two soldiers in a modern army over a purely personal matter. It is more like a dispute between two leaders of allied nations (at war with a third nation) over a public matter, which risks to break the alliance asunder. To conclude, we must say that it is true that the Homeric heroes seek to uphold their honour even at the expense of letting down the group. This is not only a matter of personal interest, but also a public duty towards their clan. Furthermore, honour in the Archaic times was so constitutive of who you are that it could not be given up easily for the sake of others, as may be the case today: in those days a person without honour was considered a non-person, a nobody. Thus I would not call Achilles behaviour selfish or individualistic.

4.3.2

THE MODERN UNDERSTANDING OF THESE TERMS, IMPLICIT IN OUR ORDINARY LANGUAGE, CANNOT BE USED TO EVALUATE THE HOMERIC HEROES

We have argued above that Achilles and Agamemnon cannot be considered selfishnot even , using our concept of what is selfishA more radical critique of Irwin would however claim that it . is inappropriate to apply our concept of what is selfish Archaic Greek society. The terms to selfishness and individualismas we normally use them: , 1. denote malaises of modern society, that is very different from Homeric society; 2. judge the heroes and their STANDARD of goodness OUR STANDARD of goodness, hence by implicitly assume that our standard is the better of the two (since it can be used to judge the other). As regards (1) we note that in ancient society, what WE would describe typically selfish behaviour might be socially esteemed as good and appropriateThe . good question is not the in good of people in general treated as equals, but the good a hierarchically-ordered society. of For instance, it was a good thing for the hero to be mighty and to demonstrate this violently to anyone who challenged his authority. Defending one honour was a better thing than cooperats ing with others. The might that is socially valued is not a sort of sadistic pastime but a social asset that is necessary to protect one clan and inferiors in a violent world. The honour that one s defended was that of one people. Showing off one might and defending one honour, one s s s earned a good reputation among one peers and one inferiors. Such a reputation is not sought s s for one own benefit as an s unsituated individual sort of being without any social ties) but for (a the benefit of a person conceived as a socially-embedded being, whose reputation affects the well-being of his friends, family, and inferiors. Hence it is misleading to imply (as Irwin does) that seeking a good reputation is 'individualistic'. Clearly, the hero action 'does not aim primarily at s some collective goal that includes the good of other people', but within the archaic social circumstances, the actions deemed honourable for the hero did achieve collective goals that included the good of one kinsfolk and inferiors because public esteem was directly linked to such a s good. Obviously, if for Irwin, the only true 'collective' goal/good, the only true non-individualistic act, is that of the maximization of the happiness ('utility') of all human beings in a global society of equals, the hero is indeed an individualist. But this would be a Utilitarian (hence, Modern) reading of Homer!

Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM

4.3

Are the Homeric Heroes selfish and individualistic ? 4-11

From the above, and from (2), we can note a fundamental defect in Irwin work. Speaking of s Homer and his heroes, we are speaking of a system of morality, an Ethicsdifferent from ours. A , system of morality makes sense in itself, and cannot be explained in terms of a different system of morality without being denatured, oversimplified and rendered banal. Irwin attempt at s explaining the rationality of Homeric ethics (i.e. Homer way of thinking about what is s good , how the ideal person should behave ) in terms of our ethical rationality is a non-starteri.e. it , is a mistake right from the start. If you want to see what a good man is for Homer and for the Archaic Greek society you donread a chapter on Homeric ethics in a pre-university textbook. t Instead, you observe the characters Achilles and Odysseus in the poems. You see how they behave, how they take decisions, how they talk, how they relate with others. You go and read the text. And if you want to be good the Homeric sense of the word in goodthen you memorise the , actions of those heroes, as Greek children did for hundreds of years, and you seek to live as those heroes lived2. If you want to evaluate which of the two Ethical systems (Homer and ours) s is the better, you need to know both from the inside, and to observe their internal flaws (incoherencies), and not use one standard (of what constitutes the good) to judge another standard.

The difficulties in comparing different ethical theories and the problems of explaining one in terms of another is the subject of my M.A. dissertation, that evaluates Alasdair MacIntyre work in this field. s Rene Mario Micallef, 11-Dec-02 6:08 AM

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Four Modes of Inequality - DuggerDocument12 paginiFour Modes of Inequality - DuggerLana MarshallÎncă nu există evaluări

- Esl Siop SpanishDocument2 paginiEsl Siop Spanishapi-246223007100% (2)

- Morality and The Concept of The Person Among The Gahuku-Gama - by K. E. ReadDocument51 paginiMorality and The Concept of The Person Among The Gahuku-Gama - by K. E. ReadFredrik Edmund FirthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lewis-Simpson Youth and Age in The MedieDocument320 paginiLewis-Simpson Youth and Age in The Mediex pulgas locas100% (1)

- Concerning Peasants - The Underlying Cause For The Peasants - Revol PDFDocument38 paginiConcerning Peasants - The Underlying Cause For The Peasants - Revol PDFNellai ThendralÎncă nu există evaluări

- HARDY - Der Begriff Der Physis in Der Griechischen Philosophie - EM ALEMAO - 1884 PDFDocument252 paginiHARDY - Der Begriff Der Physis in Der Griechischen Philosophie - EM ALEMAO - 1884 PDFwaldisio100% (1)

- Family Politics in Early Modern Literature - Hannah CrawforthDocument274 paginiFamily Politics in Early Modern Literature - Hannah CrawforthEddie CroasdellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math g4 m3 Full ModuleDocument590 paginiMath g4 m3 Full ModuleNorma AguileraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Glencoe Mcgraw Hill Geometry Homework Practice Workbook Answer KeyDocument8 paginiGlencoe Mcgraw Hill Geometry Homework Practice Workbook Answer Keybodinetuzas2100% (1)

- A Reader's Guide To The Anthropology of Ethics and Morality - Part II - SomatosphereDocument8 paginiA Reader's Guide To The Anthropology of Ethics and Morality - Part II - SomatosphereECi b2bÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAVANAGH, Chris. An Analysis of 'Héroa' in The Greek WorldDocument140 paginiCAVANAGH, Chris. An Analysis of 'Héroa' in The Greek WorldRenan CardosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emergence of Cooperation Among EgoistsDocument13 paginiThe Emergence of Cooperation Among EgoistsIgor DemićÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Evolutionary Basis of Collective ActDocument20 paginiThe Evolutionary Basis of Collective ActPrabhakar DhoundiyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Island People: An Ethnography of Apiao, Chiloé, Southern ChileDocument282 paginiIsland People: An Ethnography of Apiao, Chiloé, Southern ChileMatías Nicanor Galleguillos Muñoz100% (1)

- Country-House Radicals 1590-1660 by H. R. Trevor-Roper (History Today, July 1953)Document8 paginiCountry-House Radicals 1590-1660 by H. R. Trevor-Roper (History Today, July 1953)Anders FernstedtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anthropology and Ethics in Common FocusDocument19 paginiAnthropology and Ethics in Common FocusAndrei NacuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 818 The Rise and Fall of The Anglo Saxon Autocracy PDFDocument249 pagini818 The Rise and Fall of The Anglo Saxon Autocracy PDFlaur5boldorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lordship and Peasant ConsumerismDocument45 paginiLordship and Peasant ConsumerismMeet AMINÎncă nu există evaluări

- Budanova V P - Varvarskiy Mir Epokhi Velikogo Pereselenia NarodovDocument2.262 paginiBudanova V P - Varvarskiy Mir Epokhi Velikogo Pereselenia NarodovPrivremenko JedanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henry Peacham (Born 1546)Document2 paginiHenry Peacham (Born 1546)Marto FeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anglo-Saxon Literature by Earle, John, 1824-1903Document124 paginiAnglo-Saxon Literature by Earle, John, 1824-1903Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Gregor - Haas - Anthropology of WarCap5 PDFDocument11 paginiGregor - Haas - Anthropology of WarCap5 PDFMaki65Încă nu există evaluări

- Gender and The Chivalric CommunityDocument281 paginiGender and The Chivalric CommunityRangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Factors of Prosocial BehaviourDocument2 paginiCultural Factors of Prosocial Behaviourlightinthebox95Încă nu există evaluări

- Adkins, A. W. H. - Homeric Values and Homeric Society - JHS, 91 - 1971!1!14Document15 paginiAdkins, A. W. H. - Homeric Values and Homeric Society - JHS, 91 - 1971!1!14the gatheringÎncă nu există evaluări

- STONE, Lawrence. Social Mobility en EnglandDocument41 paginiSTONE, Lawrence. Social Mobility en EnglandTiago BonatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede Model in ContextDocument26 paginiDimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede Model in ContextSofía MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agustin Fuentes, Linda D. Wolfe Primates Face To Face The Conservation Implications of Human-Nonhuman Primate Interconnections Cambridge Studies in Biological and Evolutionary AnthDocument360 paginiAgustin Fuentes, Linda D. Wolfe Primates Face To Face The Conservation Implications of Human-Nonhuman Primate Interconnections Cambridge Studies in Biological and Evolutionary AnthAldo LuissiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weird Way of Thinking Has Prevailed WorldwideDocument2 paginiWeird Way of Thinking Has Prevailed WorldwidegarlicpresserÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ottoman Political Thought Up To The Tanz PDFDocument221 paginiOttoman Political Thought Up To The Tanz PDFWilfred Wazir NiezerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wickham. The Other Transition. From The Ancient World To FeudalismDocument34 paginiWickham. The Other Transition. From The Ancient World To FeudalismMariano SchlezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000) - Fairness and Retaliation - The Economics of Reciprocity.Document55 paginiFehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000) - Fairness and Retaliation - The Economics of Reciprocity.Anonymous WFjMFHQÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chretien Detroyes-Four Arthurian Romances SsDocument331 paginiChretien Detroyes-Four Arthurian Romances SsjanicemorrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jan de Vries The Economic Crisis of The Seventeenth Century After Fifity YearsDocument45 paginiJan de Vries The Economic Crisis of The Seventeenth Century After Fifity YearsM. A. S.Încă nu există evaluări

- The Nature and Nurture of MoralityDocument9 paginiThe Nature and Nurture of MoralityBruce McNamaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Consolidation of Noble Power in EuropeDocument72 paginiThe Consolidation of Noble Power in EuropeHugo André Flores Fernandes AraújoÎncă nu există evaluări

- DAVIES - Acts of Giving PDFDocument261 paginiDAVIES - Acts of Giving PDFMariel Perez100% (2)

- The Evolution of Service NobilitiesDocument27 paginiThe Evolution of Service NobilitiesHugo André Flores Fernandes AraújoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thompson - The Literacy of The Laity in The Middle AgesDocument217 paginiThompson - The Literacy of The Laity in The Middle AgesMajtyÎncă nu există evaluări

- HALLPIKE, C. R. The Foundations of Primitive Thought PDFDocument527 paginiHALLPIKE, C. R. The Foundations of Primitive Thought PDFRenan CardosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Book of The Governor Thomas ElyotDocument560 paginiThe Book of The Governor Thomas ElyotCezara Ripa de MilestiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reduced - The Reformation and The Disenchantment of The World ReassessedDocument33 paginiReduced - The Reformation and The Disenchantment of The World Reassessedapi-307813333Încă nu există evaluări

- Forbidden Pleasures - Sumptuary Laws and The Ideology of Moral Decline in Ancient RomeDocument383 paginiForbidden Pleasures - Sumptuary Laws and The Ideology of Moral Decline in Ancient RomeМилан Вукадиновић100% (1)

- Feudal System in Medieval Europe GNDocument7 paginiFeudal System in Medieval Europe GNAchintya MandalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Africa VampiresDocument243 paginiAfrica Vampiresmusic2850Încă nu există evaluări

- Haunted Hoccleve - The Regiment of Princes, The Troilean Intertext, and Conversations With The DeadDocument38 paginiHaunted Hoccleve - The Regiment of Princes, The Troilean Intertext, and Conversations With The DeadRone SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brills Companion To The Reception of Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism in The Middle Ages and The Renaissance (Ed. Irene Caiazzo)Document513 paginiBrills Companion To The Reception of Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism in The Middle Ages and The Renaissance (Ed. Irene Caiazzo)John Lorenzo HickeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Cohabitation Religieuse Das Les Villes Européennes, Xe-XVe SieclesDocument326 paginiLa Cohabitation Religieuse Das Les Villes Européennes, Xe-XVe SieclesJosé Luis Cervantes Cortés100% (1)

- Boulton Notion of ChivalryDocument44 paginiBoulton Notion of ChivalrykaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aristocracy. Nobility. GentryDocument6 paginiAristocracy. Nobility. GentryDamianPanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perspectives On Traditional Settlements and CommunitiesDocument200 paginiPerspectives On Traditional Settlements and Communitieskawashima ayumuÎncă nu există evaluări

- (1903) Introduction To The Study of English HistoryDocument500 pagini(1903) Introduction To The Study of English HistoryHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- White, Richard. 2005. Herder. On The Ethics of NationalismDocument16 paginiWhite, Richard. 2005. Herder. On The Ethics of NationalismMihai RusuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shame and Moral Truth in Plato S Gorgias The RefDocument32 paginiShame and Moral Truth in Plato S Gorgias The RefmartinforcinitiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adkins, A W H, Homeric Values and Homeric SocietyDocument15 paginiAdkins, A W H, Homeric Values and Homeric SocietyGraco100% (1)

- Bill Ashcroft - On Post-Colonial Futures (Writing Past Colonialism Series) (2001, Continuum)Document177 paginiBill Ashcroft - On Post-Colonial Futures (Writing Past Colonialism Series) (2001, Continuum)Rhiddhi SahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why The Center Can't HoldDocument367 paginiWhy The Center Can't HoldJorge Rodríguez100% (1)

- Amélie O. Rorty Explaining Emotions 1980 PDFDocument553 paginiAmélie O. Rorty Explaining Emotions 1980 PDFVasilisa FilatovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AZAR, Gat - Clausewitz and The Marxists - Yet Another LookDocument22 paginiAZAR, Gat - Clausewitz and The Marxists - Yet Another LookGustavo PereiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyDe la EverandAvicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06 Beyond NaturalismDocument31 pagini06 Beyond NaturalismDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- 07 Saving The PhenomenaDocument18 pagini07 Saving The PhenomenaDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- 05 The Milesian NaturalistsDocument18 pagini05 The Milesian NaturalistsDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- 03 What Helped Philosophy DevelopDocument4 pagini03 What Helped Philosophy DevelopDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STD100% (1)

- 02 Think Tank's AttitudeDocument6 pagini02 Think Tank's AttitudeDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Knowledge? What Is Right And/or Wrong About Thinking That Knowledge Is Justified True Belief?Document13 paginiWhat Is Knowledge? What Is Right And/or Wrong About Thinking That Knowledge Is Justified True Belief?Dr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harry Frankfurt and SufficiencyDocument8 paginiHarry Frankfurt and SufficiencyDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subjective Rights and Human Rights in Habermas - The Legal and Moral Elements of A Cosmopolitan Political Theory.Document77 paginiSubjective Rights and Human Rights in Habermas - The Legal and Moral Elements of A Cosmopolitan Political Theory.Dr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Application of Multivariate Analytical Techniques To The Study of Marine Benthic Assemblages. Xjenza 3:2 (1998) 9-28Document21 paginiThe Application of Multivariate Analytical Techniques To The Study of Marine Benthic Assemblages. Xjenza 3:2 (1998) 9-28Dr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nozick, Taxation and The Wilt Chamberlain ExampleDocument7 paginiNozick, Taxation and The Wilt Chamberlain ExampleDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Relativist and Perspectivist Challenges To MacIntyre S Meta-EthicsDocument39 paginiThe Relativist and Perspectivist Challenges To MacIntyre S Meta-EthicsDr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is There Such A Thing As Personal Identity?Document15 paginiIs There Such A Thing As Personal Identity?Dr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Does The World Contain Any Objective Feature of Rightness and Wrongness?Document15 paginiDoes The World Contain Any Objective Feature of Rightness and Wrongness?Dr René Mario Micallef, SJ, STDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavioral Perspectives in PersonalityDocument11 paginiBehavioral Perspectives in PersonalityMR2692Încă nu există evaluări

- Icon Model On ConstructivismDocument1 paginăIcon Model On ConstructivismArnab Bhattacharya67% (3)

- Heraclitus - The First Western HolistDocument12 paginiHeraclitus - The First Western HolistUri Ben-Ya'acovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Üds 2011 Sosyal Ilkbahar MartDocument16 paginiÜds 2011 Sosyal Ilkbahar MartDr. Hikmet ŞahinerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stenberg & Kaufman - The International Handbook of Creativity PDFDocument540 paginiStenberg & Kaufman - The International Handbook of Creativity PDFmaria19854100% (19)

- Mqa 1Document1 paginăMqa 1farazolkifliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Portfolio in Mother Tongue-1Document18 paginiPortfolio in Mother Tongue-1Jehana DimalaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q5. Teaching Styles (CAPEL's Book Excerpt)Document10 paginiQ5. Teaching Styles (CAPEL's Book Excerpt)Leonardo Borges MendonçaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HackerDocument3 paginiHackerNikki MeehanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bohol Mil q3 PLP Wk2Document7 paginiBohol Mil q3 PLP Wk2Nelia AbuevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- E-Shala Learning HubDocument8 paginiE-Shala Learning HubIJRASETPublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLL - English 5 - Q3 - W6Document14 paginiDLL - English 5 - Q3 - W6Veronica EscabillasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Cycle Costing PDFDocument25 paginiLife Cycle Costing PDFItayi NjaziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sexing The CherryDocument8 paginiSexing The CherryAndreea Cristina Funariu100% (1)

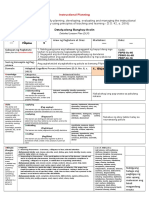

- Lesson 2. WHAT IS AGROTECHNOPRENEURSHIPDocument23 paginiLesson 2. WHAT IS AGROTECHNOPRENEURSHIPRhea Jane DugadugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Job Description Associate Attorney 2019Document5 paginiJob Description Associate Attorney 2019SAI SUVEDHYA RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structural Functionalism of MediaDocument3 paginiStructural Functionalism of Mediasudeshna860% (1)

- Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade 6-Justice: Schools Division of Misamis Oriental Kimaya Integrated SchoolDocument16 paginiWeekly Home Learning Plan Grade 6-Justice: Schools Division of Misamis Oriental Kimaya Integrated SchoolDaling JessaÎncă nu există evaluări

- School To Club Sport Transition: Strategy and Product Design EssentialsDocument8 paginiSchool To Club Sport Transition: Strategy and Product Design EssentialsSamuel AyelignÎncă nu există evaluări

- 99 Free Homeschooling Resources-ToolsDocument3 pagini99 Free Homeschooling Resources-ToolsDivineDoctor100% (1)

- DLP in Filipino For Observation RevisedDocument4 paginiDLP in Filipino For Observation RevisedLissa Mae Macapobre100% (1)

- SITRAIN Brochure Sep 12 PDFDocument6 paginiSITRAIN Brochure Sep 12 PDFPaul OyukoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Catalogue 2017 2018Document113 paginiCourse Catalogue 2017 2018adityacskÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vlogging As The Tool To Improve Speaking Skills Among Vloggers in MalaysiaDocument12 paginiVlogging As The Tool To Improve Speaking Skills Among Vloggers in MalaysiaZulaikha ZahrollailÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iot-Based Building Automation and Energy ManagementDocument13 paginiIot-Based Building Automation and Energy ManagementMy PhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture, Theory, and Narrative - The Intersection of Meanings in PracticeDocument10 paginiCulture, Theory, and Narrative - The Intersection of Meanings in PracticepepegoterayalfmusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACADEMIC MANUAL - National Institute of Fashion TechnologyDocument455 paginiACADEMIC MANUAL - National Institute of Fashion TechnologyRalucaFlorentinaÎncă nu există evaluări