Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Child Labour & The Industrial Revolution: Textile Factories

Încărcat de

Alessandra TottoliTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Child Labour & The Industrial Revolution: Textile Factories

Încărcat de

Alessandra TottoliDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Child Labour & The Industrial Revolution During the 1800s the Industrial Revolution spread throughout Britain.

The use of steam-powered machines, led to a great increase in the number of factories (especially in textile factories or mills). As the number of factories grew, people from the countryside began to move into the towns looking for better paid work. The wages of a farm worker were very low and there were less jobs working on farms because of the invention and use of new machines such as threshers. Not only worked lots of women but also children. Many factory workers were children. They worked long hours and were often treated badly by the supervisors or overseers. Sometimes the children started work as young as four or five years old. A young child could not earn much, but even a few pence would be enough to buy food. Coal Mines Many children worked in coal mines which were dangerous places where roofs sometimes caved in, explosions happened and workers got all sorts of injuries. There were very few safety rules. The younger children often worked as "trappers" who worked trap doors. They sat in a hole hollowed out and held a string which was fastened to the door. When they heard the coal wagons coming they had to open the door by pulling the string. This job was one of the easiest down the mine but it was very lonely and the place were they sat was usually damp and draughty. Older children worked as "coal bearers" carrying loads of coal on their backs in big baskets. In 1842, the Government passed The Mines Act, forbidding the employment of women and girls and all boys under the age of teen down mines. Later it became illegal for a boy under 12 to work down a mine. Mills While thousands of children worked down the mine, thousands of others worked in the cotton mills. The mill owners often took in orphans to their workhouses, they lived at the mill and were worked as hard as possible. They spent most of their working hours at the machines with little time for fresh air or exercise. Even part of Sunday was spent cleaning machines. There were some serious accidents, some children were scalped when their hair was caught in the machine, hands were crushed and some children were killed when they went to sleep and fell into the machine. Factories Children often worked long hours in match factories, where children were employed to dip matches into a chemical called phosphorous. This phosphorous could cause their teeth to rot and some died from the effect of breathing it into their lungs. Many parents were unwilling to allow their children to work in these new textile factories. To overcome this problem factory owners had to find other ways of obtaining workers. One solution to the problem was to buy children from orphanages and workhouses. The children became known as pauper apprentices. This involved the children signing contracts that made them the property of the factory owner. Factory owners were responsible for providing their pauper apprentices with food. In most textile mills the children had to eat their meals while still working. This meant that the food tended to get covered with the dust from the cloth. Sarah Carpenter was a child worker: "Our common food was oatcake. It was thick and coarse. This oatcake was put into cans. Boiled milk and water was poured into it. This was our breakfast and supper. Our dinner was potato pie with boiled bacon it, a bit here and a bit there, so thick with fat we could scarce eat it, though we were hungry enough to eat anything. Tea we never saw, nor butter. We had cheese and brown bread once a year. We were only allowed three meals a day though we got up at five in the morning and worked till nine at night."

Chimney Sweeps Although in 1832 the use of boys for sweeping chimneys was forbidden by law, boys continued to be sold for little money to a master. He exploited these little boys because they were very small and could easily climb up the chimneys. When they first started at between five and ten years old, children suffered from many cuts and bruises on their knees, elbows and thighs however after months of suffering their skin became hardened. Street Children There were also some children who were homeless, with no regular money. They were often orphans with no-one who care for them. They stole or picked pockets to buy food and slept in outhouses or doorways. Charles Dickens wrote about these children in his book "Oliver Twist". Some street children did jobs to earn money. They could work as crossing-sweepers, sweeping a way through the mud and horse dung of the main paths to make way for ladies and gentlemen. Others sold lace, flowers, matches or muffins etc out in the streets. Country Children Poor families who lived in the countryside were also forced to send their children out to work. Children who were seven and eight year olds could work as bird scarers, out in the fields from four in the morning until seven at night. Changes for the better It took time for the government to decide that working children ought to be protected by laws while many people did not see anything wrong with the idea of children earning their keep. They also believed that people should be left alone to help themselves. For example, the journalist, Edward Baines, defended the employment of young children as piecers and scavengers: "It is not true to represent the work of piecers and scavengers as continually straining. None of the work in which children and young persons are engaged in mills require constant attention. It is scarcely possible for any employment to be lighter. The position of the body is not injurious: the children walk about, and have the opportunity of frequently sitting if they are so disposed." People such as Lord Shaftesbury and Sir Robert Peel worked hard to persuade the public that it was wrong for children to suffer health problems and to miss out on schooling due to work. In 1832, Sadler introduced a Bill in the House of Common that reduced working hours of all people under the age of 18 to ten hours a day. After much debate the Bill didnt pass. Sadler interviewed 50 people who had worked in factories as children and he discovered that it was common for very young children working for over twelve hours a day. Lord Ashley delivered a speech in which he claimed that ten hours is the utmost amount of working hours which can be endured by children without damaging their health. Children who were late for work were severely punished. If children arrived late for work they would also have money deducted from their wages. Time-keeping was a problem for those families who could not afford to buy a clock. In some factories workers were not allowed to carry a watch. The children suspected that this rule was an attempt to trick them out of some of their wages.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Kids Had Jobs : Life before Child Labor Laws - History Book for Kids | Children's HistoryDe la EverandKids Had Jobs : Life before Child Labor Laws - History Book for Kids | Children's HistoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Victorian Times 87389Document4 paginiVictorian Times 87389irinasincuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Working Conditions and Legislation During The IRDocument3 paginiWorking Conditions and Legislation During The IRplaystationhome18Încă nu există evaluări

- Child Labour: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument15 paginiChild Labour: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediashailesh_spatialdimensions8629Încă nu există evaluări

- Final EssayDocument8 paginiFinal Essayapi-241425717Încă nu există evaluări

- ChungDocument12 paginiChungflagbitÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Industrial Revolution - BOOKLETDocument37 paginiThe Industrial Revolution - BOOKLETcaru1981Încă nu există evaluări

- Child Labor and Factory Legislation: History of Welfare Development in UKDocument7 paginiChild Labor and Factory Legislation: History of Welfare Development in UKGustavo MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labour PDFDocument2 paginiChild Labour PDFTyler DerdenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Year Act or Investigation TermsDocument3 paginiYear Act or Investigation TermsHella SmartÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labour: Child Labor Refers To The Employment ofDocument10 paginiChild Labour: Child Labor Refers To The Employment ofVarun PilankarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workers Exploited in Textile Factories During Industrial RevolutionDocument2 paginiWorkers Exploited in Textile Factories During Industrial RevolutionThor Batista AvengersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Claudia First DraftDocument5 paginiClaudia First Draftapi-241425717Încă nu există evaluări

- Dickens' Novels Highlight Cruelty of 19th Century Child LabourDocument2 paginiDickens' Novels Highlight Cruelty of 19th Century Child LabourMarioara CiobanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labor Refers To The Employment of Children at Regular and Sustained LaborDocument7 paginiChild Labor Refers To The Employment of Children at Regular and Sustained LaborShankar SawantÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fredrich Engels Believed That The Children Working in The Textile Mills of Great Britain Were No More Than Slaves and Were Treated As Such2Document7 paginiFredrich Engels Believed That The Children Working in The Textile Mills of Great Britain Were No More Than Slaves and Were Treated As Such2Margaret TempletonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trabalhadores São Explorados em Fábricas Têxtis Na Revolução IndustrialDocument2 paginiTrabalhadores São Explorados em Fábricas Têxtis Na Revolução IndustrialThor Batista AvengersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labour Refers To TheDocument87 paginiChild Labour Refers To TheUsama KamaalÎncă nu există evaluări

- History ProjectDocument12 paginiHistory ProjectYoussefq WessamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Working ConditionsDocument15 paginiWorking Conditionsapi-507996900Încă nu există evaluări

- Child Labour - Q & ADocument3 paginiChild Labour - Q & Athirumal rÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child LabourDocument104 paginiChild LabourMAX PAYNEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children in Victorian Times Fun Activities Games Reading Comprehension Exercis - 26230Document3 paginiChildren in Victorian Times Fun Activities Games Reading Comprehension Exercis - 26230MaryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indiatiral Revolution Case StudyDocument2 paginiIndiatiral Revolution Case Studythirumal rÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liam-Industrialization Was Unfair To KidsDocument3 paginiLiam-Industrialization Was Unfair To Kidsapi-202727113Încă nu există evaluări

- Children Who Labor Handout 2Document2 paginiChildren Who Labor Handout 2Mohammad ShahnurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Victorian Era ResearchDocument8 paginiVictorian Era Researchmiftha syahriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prezi DefinitiuDocument2 paginiPrezi DefinitiuNaomi Román BalaguéÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civic EducationDocument6 paginiCivic EducationCarmine GargaglioneÎncă nu există evaluări

- How the Industrial Revolution Changed SocietyDocument4 paginiHow the Industrial Revolution Changed Societylovesh kagraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labour: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument22 paginiChild Labour: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediales0donÎncă nu există evaluări

- IR Workers ConditionsDocument13 paginiIR Workers Conditionsbianca.janakievskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women Working Class (Industrial Revolution)Document5 paginiWomen Working Class (Industrial Revolution)Phillip Matthew Esteves MalicdemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child LabourDocument18 paginiChild LabourVikash RanjanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labour in Factories During Industrial RevolutionDocument8 paginiChild Labour in Factories During Industrial RevolutionYash29V VishwakarmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dickens perspective on disoriented childhood during industrial revolutionDocument13 paginiDickens perspective on disoriented childhood during industrial revolutionSutanwi ModakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Idustrial Revolution Causes Hard Times For ManyDocument2 paginiIdustrial Revolution Causes Hard Times For ManychavezangeliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children in Factories 2:10:20 PDFDocument2 paginiChildren in Factories 2:10:20 PDFwillow heaneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Industrial Revolution-Factories and WorkersDocument4 paginiThe Industrial Revolution-Factories and WorkersHugo VillavicencioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factories Sources SenDocument2 paginiFactories Sources SenaikamileÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Victorian WorkhousesDocument3 paginiThe Victorian Workhousesiyireland8808100% (1)

- Children and 19th-Century EnglandDocument1 paginăChildren and 19th-Century EnglandAbdo HusseinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children in Victorian Times Fun Activities Games Reading Comprehension Exercis - 26230Document4 paginiChildren in Victorian Times Fun Activities Games Reading Comprehension Exercis - 26230irinasincuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labor Final-MoralesDocument7 paginiChild Labor Final-Moralesapi-440290992Încă nu există evaluări

- The Industrious Child Worker: Child Labour and Childhood in Birmingham and the West Midlands, 1750 - 1900De la EverandThe Industrious Child Worker: Child Labour and Childhood in Birmingham and the West Midlands, 1750 - 1900Încă nu există evaluări

- Child LabourDocument13 paginiChild Labourapi-533839695Încă nu există evaluări

- In Charles Dickens's Time - Fact or FictionDocument45 paginiIn Charles Dickens's Time - Fact or FictionMr. HuntÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sheetal Rathod - Child LabourDocument46 paginiSheetal Rathod - Child Laboursunru240% (1)

- Child Labour: Labour International Organizations Universal Schooling Industrial Revolution Workers Children's RightsDocument10 paginiChild Labour: Labour International Organizations Universal Schooling Industrial Revolution Workers Children's RightsDeepak Shanmuga SundaramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early 20th century child labour in glass making industriesDocument4 paginiEarly 20th century child labour in glass making industriesAvinash MulikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labor in The Industrial Revolution Background: With The Rise of The Industrial Revolution Came The Demand For All WorkersDocument1 paginăChild Labor in The Industrial Revolution Background: With The Rise of The Industrial Revolution Came The Demand For All Workersstquinn864443Încă nu există evaluări

- Gender Roles, Labor and Family in Industrial England and FranceDocument5 paginiGender Roles, Labor and Family in Industrial England and Franceapi-276669719Încă nu există evaluări

- Child Labor FinalDocument8 paginiChild Labor Finaleye sha100% (1)

- Child LabourDocument10 paginiChild LabourSTAR GROUPSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Labor - 840LDocument7 paginiChild Labor - 840LNajwa KayyaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Working ConditionsDocument14 paginiThe Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Working ConditionsĎıʏɑÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child LabourDocument195 paginiChild Labourshiva kumar R100% (1)

- From the Cradle to the Coalmine: The Story of Children in Welsh MinesDe la EverandFrom the Cradle to the Coalmine: The Story of Children in Welsh MinesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Did Industrialization Abuse or Help Common PeopleDocument2 paginiDid Industrialization Abuse or Help Common PeopleNiki JuhászováÎncă nu există evaluări

- AISI 1018 Mild Low Carbon Steel PDFDocument3 paginiAISI 1018 Mild Low Carbon Steel PDFFebrian JhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comprehensive equipment listDocument407 paginiComprehensive equipment listКари МедÎncă nu există evaluări

- KUMWOO Valves General CatalogDocument28 paginiKUMWOO Valves General CatalogJaveed A. Khan100% (1)

- Sand Casting: - The Pattern Is Intentionally Made Larger Than The Cast Part To Allow For Shrinkage During CoolingDocument21 paginiSand Casting: - The Pattern Is Intentionally Made Larger Than The Cast Part To Allow For Shrinkage During CoolingPalaash ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- DORIAN - 80 20 eDocument36 paginiDORIAN - 80 20 eAngel Eduardo Lopez SantanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentasi Teknologi Mekanik Minggu 10 (Bor)Document19 paginiPresentasi Teknologi Mekanik Minggu 10 (Bor)ibnuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workshop Manual 2016 PDFDocument62 paginiWorkshop Manual 2016 PDFgiridharrajeshÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1328699325305-Gr B Ans PT 2Document93 pagini1328699325305-Gr B Ans PT 2Sankati SrinivasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grinding and Economics of Machining OperationDocument31 paginiGrinding and Economics of Machining Operationاحمد عمر حديدÎncă nu există evaluări

- The principle of knitting and basic knitted structuresDocument26 paginiThe principle of knitting and basic knitted structuresPulak Debnath100% (2)

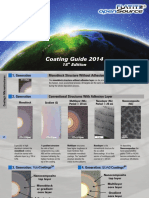

- Coating Guide Ev4 PreviewDocument9 paginiCoating Guide Ev4 Previewmaryam KAHRIZIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operator's ManualDocument405 paginiOperator's ManualParamasivam VeerappanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Machining Operations and Machine Tools: J.Ramkumar Dept of Mechanical EngineeringDocument36 paginiMachining Operations and Machine Tools: J.Ramkumar Dept of Mechanical EngineeringOm PrakashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indesit Wg935tpf (ET)Document30 paginiIndesit Wg935tpf (ET)Richard PortelliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Replacing The X Belt 1V6P MachineDocument6 paginiReplacing The X Belt 1V6P MachinejoecentroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yue Hing: Y101 Fixed Type Fire Hose ReelDocument2 paginiYue Hing: Y101 Fixed Type Fire Hose ReelSatish Kumar MauryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is 2974 Part 3 Design and Construction of Machine Foundations Code of Practice Part 3 Foundations For Rotary Type Machines Medium and Hih FrequencyDocument15 paginiIs 2974 Part 3 Design and Construction of Machine Foundations Code of Practice Part 3 Foundations For Rotary Type Machines Medium and Hih Frequencymahbub1669Încă nu există evaluări

- Industrial LossesDocument22 paginiIndustrial Losses78kbalajiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 507 Chapter PagesDocument88 pagini507 Chapter PagesFazry NurokhmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- TM9-1900 Ammunition General, June 1945Document339 paginiTM9-1900 Ammunition General, June 1945Thomas Conroy-RunyonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crosby Mckissick Sheaves Catalog PDFDocument29 paginiCrosby Mckissick Sheaves Catalog PDFSumanth ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Variable Costing For Management AnalysisDocument14 paginiVariable Costing For Management AnalysisJanicaNoiraC.ZunigaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delphi Car AppsDocument2.645 paginiDelphi Car AppsvizirucostiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is 13349Document20 paginiIs 13349raji357100% (1)

- LatheDocument14 paginiLatheHimanshu ModiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Micro MachiningDocument302 paginiMicro Machiningapulavarty100% (2)

- Construction Schedule For Sewege Treatment PlantDocument22 paginiConstruction Schedule For Sewege Treatment PlantEngr Adnan Naseem100% (3)

- Sample Sap PP Business BlueprintDocument36 paginiSample Sap PP Business BlueprintVenkateswararao Pothini100% (2)

- Dam-Mont Company Presentation 2014Document25 paginiDam-Mont Company Presentation 2014zele87Încă nu există evaluări

- CNC Part Programming (Milling)Document4 paginiCNC Part Programming (Milling)Nejmal SalimÎncă nu există evaluări