Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Counseling

Încărcat de

Jithin KrishnanDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Counseling

Încărcat de

Jithin KrishnanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

My Stance on Assessment by Amanda Southwell (nee Croucher) Introduction There are a wide variety of issues raised by assessment and

the form of its application. Many counselling agencies utilise a range of assessment procedures and techniques, including pre-counselling interviews and diagnostic testing. Individual counsellors approach assessment according to the particular theoretical model to which they adhere and may apply qualitative measuring tools accordingly. Assessment, therefore, is a generic and often confusing term, referring both to the process and content within counselling practice. Throughout this essay I will endeavour to discuss a portion of methods and techniques, placing assessment within the modernist and postmodernist theoretical frameworks, and in doing so present both positive and cautionary aspects. Finally, I will conclude with my own reflection of assessment, providing reasons for my adopted stance. Diagnosis as Assessment Diagnosis is concerned with classifying a problem, matching signs and symptoms of a client with a known category of disorder or dysfunction. DSM IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) The purpose of the DSM IV is made evident in its introduction: to provide clear descriptions of diagnostic categories in order to enable clinicians and investigators to diagnose, communicate about, study, and treat people with various mental disorders. (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV, p. xxvii). Certain conditions make counselling difficult, such as counselling someone who is actively hallucinating or suffering from schizophrenia. It is essential, therefore, that counsellors should be aware of the major psychiatric disorders outlined in the DSM IV. However, the proper use of the criteria requires specialised clinical training, thus rendering it difficult to apply in mainstream counselling. Many also believe that using such a means to classify a client may turn the person into a thing, an object of study rather than a complex changing individual (Palmer & McMahon, 1997, p. 8). Individual responsibility, disability, determination, and competency are not taken into account, all of which may be relevant in such cases as Pathological

Gambling. Certain advances have been made, however. The consistently problematic issue of cross-cultural assessment has now been addressed in a new culture-specific section in the text, the inclusion of a glossary of culture-bound syndromes, and the provision of an outline for cultural formulation designed to enhance the cross-cultural applicability of the DSM IV. The Mental Status Exam The MSE differs chiefly from such assessment tests as the DSM IV in that it is essentially a record of the counsellors observations during the interview, rather than a factual analysis of symptoms, or a report by family, friends, or another professional. By analysing appearance, behaviour, speech, mood, depersonalisation, obsessional traits, delusions, orientation, concentration, memory and insight throughout the session, the counsellor can gain information about the client and their emotional difficulties in the hereand-now as well as in the past. Significant risk factors can be identified, and it is a useful tool for assessing a client over time. Counsellors must, however, guard against the wish to prematurely infer meaning from what the counsellor is actually seeing, and the temptation to see things that are really the counsellors own assumptions. Multimodal Therapy Multimodal assessment, developed by Arnold Lazarus, examines each area of a persons BASIC I.D.: Behaviour, Affect, Sensation, Imagery, Cognition, Interpersonal relationships, and Drugs/Biology. A fundamental premise is that patients are usually troubled by a multitude of specific problems that should be dealt with by a similar multitude of specific treatments. It provides an operational way of answering the constant inquiry: Who or what is best for this individual (or couple, or family, or group)? The Multimodal approach has an eclectic, integrative perspective, and continual scanning of each modality and its interaction with every other can enhance a counsellors effectiveness and awareness of the clients chief problems. It can also be adapted for use extending from individuals, couples, families, and groups to broader community and organised settings. However, the average duration of a complete course of Multimodal therapy is approximately 50 hours, clients may become overwhelmed by too many questions, and therapists may ignore presenting problems in favour of the modality assessment. Individualised Assessment The application of different forms of diagnosis or testing has the potential to emphasise powerful forces that are mysterious to the client, and give therapists an overly certain sense of explanation. Individualised

Assessment makes use of formalised diagnostic assessments, but goes further to describe the clients particular situation, and the way in which he or she influences outcome, both positively and problematically. Tests are only turned to after a collaborative relationship is established between the counsellor and client, and because [they] are working together to see what new understandings might emerge, clients do not feel they are being objectified or having their privacy invaded (Fischer, 1985, p. 42). Assessment moves beyond the tester as scientist whose task is to identify the patients traits, defences and symptoms through measurement, to a concurrent involvement of assessor and client using everyday, shared language. Qualitative Methods of Assessment In keeping with the need for greater client involvement, humanistic oriented counsellors often employ qualitative methods of assessment where the client participates actively in learning/assessment exercises integrated into the counselling sessions themselves. These include the uses of a lifeline to map significant experiences along a life continuum, the Likert scale or those similar, determining the strengths of experiences and feelings using numbered intensities, and the genogram, to name but a few. The genogram, in particular, is a useful tool used widely in family therapy. A central principle agreed upon by systemic family therapists is that clients are connected to living systems and that change in one part of the unit reverberates throughout other parts (Corey, 1996, p. 367). The genogram, originally founded by Bowen in his studies on family systems therapy is a useful tool for mapping (McGoldrick & Gerson, 1985, p. 3). By scanning the family system historically and assessing previous life cycle transitions, present issues can be placed within the context of the familys evolutionary patterns. Clients can recognise how their own circumstances may relate to possible destructive patterns that have been maintained throughout the generations before them, therefore enabling family members to alter these patterns. It also allows clinicians to get to know the family, and easily record data which may otherwise be given in an ad hoc fashion. While some recommend that the genogram should be constructed in the first session, it is of utmost importance that the counsellor is flexible as to timing, as the cases of each client or group may not warrant the time spent on compilation. In addition there remains the danger of genograms being used inappropriately as an easy tool, or as a way of avoiding or intellectualising away very current conflicts. It is easy to forget that the purpose of therapy is to bring about changes, not record elegant diagrams. Involving a client or family in qualitative methods of assessment enables them to be placed in the expert position, teaching the therapist. The following theories sustain a similar discourse.

Person-Centred Therapy A significant shift away from the objectivistic, measurement approach to assessment is indicated in the work of Carl Rogers. As described by Palmer and McMahon (1997): The concepts of assessment, diagnosis and treatment are seen by most person-centred therapists as compromising genuineness a cornerstone of the person-centred framework as the client is viewed in an objective manner. The major person-centred objection is to expertise: it is anathema to think that an expert knows another person better than she knows herself (p. 15). What mattered to Rogers was not how or by what means the counsellor assessed the client, but how the client assessed him or herself. In his own words, the opportunities for new learning are maximised when we approach the individual without a preconceived set of categories which we expect him to fit (Rogers, 1965, p. 497). The client is seen as having the sole potential of knowing fully the dynamics of his perceptions and behaviour, and the constructive forces bringing about reorganisation of self and relearning reside primarily in him. To Rogers, diagnosis could be unwise and detrimental, as the locus of evaluation shifts so definitively in the expert that dependent tendencies may develop in the client, who may also develop a belief that the measure of his personal worth lies in the hands of another. Considerations of such a nature have led person-centred therapists to minimise the diagnostic process as a basis for therapy. Rogers admitted, however, that tests may have a place, especially if they were used toward the conclusion of counselling and if the client requested them, but recommended caution in using tests or in taking a complete case history at the outset. Postmodernism and Narratives The belief in progress, rationality, and scientific theories are now seen as characteristics of modernity. Many believe we are currently moving into a postmodern era. While modernist thinkers tend to be concerned with facts and rules, postmodernists are concerned with meaning, salience of cultural difference and deconstruction of realities. The implication for counselling is a movement away from the modernist grand theories of those such as Freudtowards a much more fragmented, locally or personally constructed integrationist or eclectic approach to knowledge (McLeod, 1998, p. 221). Postmodernism espouses that people live their lives within the dominant narratives or knowledges of their culture and family, and the significance of story-telling and narrative are a primary means of making sense of social experience and communication with others. However, the dominant cultures in which people live can construct narratives that impoverish the actual life experience of the person and their own

stories. Postmodern narrative therapists believe that when life narratives offer only unpleasant choices or carry hurtful meanings, they can be altered by highlighting different, previously un-storied events or by creating new meaning from already-storied. Thus, new narratives are constructed. A characteristic of the modernist approach to stories is to explain them through underlying structures or archetypes instead of letting them tell themselves. Thus, only the expert can understand the story. Postmodern therapists believe that there are no prior meanings hiding in stories or texts. A therapist with this view will expect a new, more useful narrative to surface, but the conversation, not the therapist, is its author. In the words of Freedman and Combs (1996): When therapists listen to peoples stories with an ear to making an assessment or taking a history of the illness or offering an interpretation, they are approaching peoples stories from a modernist, structuralist worldview. In terms of understanding an individual persons specific plight or joining her in her worldview, this approach risks missing the whole point (p.31). Postmodernism rejects what Foucault (1980) terms global unitary knowledges, (as cited in Wood, 1997, p. 24) such as the DSM IV as the only sources of truth when working with people. A postmodernist view of history-taking accepts that this process is always subjective, always coconstructed. Having a knowledge base or attachment to a theory can undermine and devalue the unique experience of the client, as can holding information and opinions on the patient that the latter is unaware of, and might even disagree with. Conclusion Palmer and McMahon (1997) reiterate that assessment must begin with an open mind on behalf of the counsellor, a readiness to enter into anothers world (p. 93). However, they also imply that formalised assessment is an essential component of the therapeutic process, usually beginning at the first point of contact with the client. I would tend to disagree, on the basis that this stance places the counsellor as expert, and is in danger of diminishing or even nullifying collaboration between the client and counsellor. This is not to suggest that a more structured form of assessment is inappropriate. Certain circumstances certainly call for a more rigid diagnosis, based on perhaps the agency worked for, or the needs of a mentally ill or suicidal client. In other situations, measurement or qualitative tools, such as the lifeline and genogram, may be of use to allow clients to carry out their own explorations. Assessment tools have been created for a purpose, all of which may have merit, some of which, in my view, are more effective than others. The discretion of the counsellor is vital in determining which to employ. On the other hand, to discredit the post-modernist and person-centred view of clients as being the interpreters of their own

experience, in favour of assessment as procedure, is to condone a hierarchy whereby the counsellor knows more about a persons lived experience than the person does. The dismissal of any of the above without careful consideration would seem to me to be injurious to the counselling process. Each must be weighed in the light of the theoretical framework adopted by the counsellor, the needs of the client, and the specific situation at hand. In my opinion, a simple but fundamental law can encompass all facets of assessment, and is described by Egan (1998): Assessment, then, is not something helpers do to clientsRather, it is a kind of learning in which, ideally, both client and helper participate (p. 116). References Corey, G. (1996). Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy. California: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition). American Psychiatric Association. Egan, G. (1998). The Skilled Helper: A Problem-Management Approach to Helping. California: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. Freedman, J. & Combs, G. (1996). Narrative Therapy: The Social Construction of Preferred Realities. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Fischer, C. T. (1985). Individualising Psychological Assessment. California: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. McLeod, J. (1998). An Introduction to Counselling. Philadelphia: Open University Press. Mc.Goldrick, M. & Gerson, R. (1985). Genograms in Family Assessment. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Palmer, S. & McMahon, G. (1997). Client Assessment. London: Sage Publications. Rogers, C. (1965). Client-Centered Therapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Wood, C. (1997). To Know or Not To Know: A Critique of Postmodernism in Social Work Practice. Australian Social Work, 50 (3), 21-27.

LIFESTYLE ANALYSIS QUESTIONS 1: Do you have any on-going health problems? If so, what are they? (Please enter information into the box below, be brief and concise!) 2: Do your eyes ever ache? 3: Do you ever have hearth burn? 4: Do you ever have gas? 5: Do you ever have ringing in your ears? 6: Do you use any tobacco products? 7: Do you have night blindness? 9: Do your gums ever bleed? 10: Do you have bad breath? 11: Do you have nasal congestion? 12: Do you have sinus congestion? 13: Do meats and milk products give you gas? 14: Are you ever constipated? 15: Do you use laxatives? 16: Do you ever have diarrhea? 17: Do you have hemorrhoids? 18: Do you have joint aches? 19: Are your hands and feet sometimes colder than the rest of your body? 20: Do you sweat easily with mild exercise? 21: Are the glands in your jaw or armpit ever sore to the touch? 22: Do you have any skin problems? 23: Do any of your nails grow at different rates than other nails? 24: Is the color the same under all nails? 25: Are your teeth overly sensitive? 26: Do you think your libido is normal? 27: Would you like it to be better than it is? 28: Do you use any anti-perspirants? 29: Do you urinate frequently or in small quantities? 30: Are you taking any medication whatsoever? 31: Have you taken any medications in the past? 32: Did any doctor ever diagnose you with any condition that you still have such as hypertension, arthritis, etc.? Please name the condition(s): 33: Do you think you could feel better? 34: Do you consider yourself agile? 35: Do you sleep soundly? 36: Do you crave sugar or white flour products? 37: Tell me about your normal consumption of sweets each week? 38: How much water each day do you drink? 39: How fast does your hair grow? 40: How much coffee do you drink each day? 41: How much soda pop do you drink each day? 42: How much alcohol each week do you consume? 43: Do you have headaches? 44: How often do you have headaches? 45: If you have headaches, when do you most often have them? Please describe your headaches as briefly as possible:

46: What is your weight? (Lbs. or Kg) Select: Lbs or Kg 47: What is your height (Ft/In or Mtrs/Cm)? Select: Ft/In or CM 48: How do you feel generally? Please enter your own brief comments to question 48 below:

49: How many hours a night do you sleep? 50: Do you do any non-work related exercise? Please enter a brief answer in the box: (Jog daily, gym workout, bike, etc.) 51: Please describe the following as briefly as possible: 1) Typical breakfast, 2) Typical lunch, 3) Typical supper, and 4) Typical snacks:

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Lezak. Neuropsychological Assessment (5th Edition)Document1.576 paginiLezak. Neuropsychological Assessment (5th Edition)Anneliese Fuentes95% (107)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Performance Appraisal Project ReportDocument36 paginiPerformance Appraisal Project Reportkamdica90% (88)

- Performance Appraisal Project ReportDocument36 paginiPerformance Appraisal Project Reportkamdica90% (88)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- 1618008-The Risk and Protective Factors of Pornography AddictionDocument30 pagini1618008-The Risk and Protective Factors of Pornography AddictionJaz MnÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA Scheme and Syllabus SmbsDocument6 paginiMBA Scheme and Syllabus SmbsJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ion Study - Guide LinesDocument7 paginiIon Study - Guide LinesManisha NeelakandhanÎncă nu există evaluări

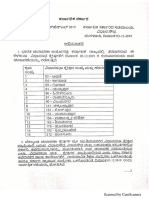

- By Election Day Holiday Notification PDFDocument3 paginiBy Election Day Holiday Notification PDFJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- CurriculumDocument35 paginiCurriculumJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Os Guide LinesDocument8 paginiOs Guide LinesJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Character Certificate For Ibps Clerk Po Common Interview 2013 2014Document1 paginăCharacter Certificate For Ibps Clerk Po Common Interview 2013 2014Vipin DixitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Character Certificate For Ibps Clerk Po Common Interview 2013 2014Document1 paginăCharacter Certificate For Ibps Clerk Po Common Interview 2013 2014Vipin DixitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strike - 02.09.2016. NOBO - Not A PartyDocument1 paginăStrike - 02.09.2016. NOBO - Not A PartyJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Document4 pagini2Jithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- HRO Providers QuestionnaireDocument3 paginiHRO Providers QuestionnaireJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAIIB Financial Module D MCQDocument7 paginiCAIIB Financial Module D MCQRahul GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAIIB Financial Module D MCQDocument7 paginiCAIIB Financial Module D MCQRahul GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biyani's Think Tank Advertisement Mana Ement: Conce T Based NotesDocument42 paginiBiyani's Think Tank Advertisement Mana Ement: Conce T Based NotesJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Industrial Employment (Standing Order) Act, 1946Document11 paginiIndustrial Employment (Standing Order) Act, 1946Pradyumna Kumar AtriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imp GL CodesDocument6 paginiImp GL CodesJithin Krishnan100% (1)

- The Child LabourDocument6 paginiThe Child LabourJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jaiib Accfinance MCQDocument11 paginiJaiib Accfinance MCQmedical officer Phc Amala VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial AnalysisDocument87 paginiFinancial AnalysisJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- InventorDocument16 paginiInventorJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Qualifications of Test Users - FinalDocument4 paginiQualifications of Test Users - FinalJithin Krishnan100% (1)

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument3 paginiNew Microsoft Word DocumentJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top Indian Advertising AgenciesDocument3 paginiTop Indian Advertising AgenciesGeorge D BonisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mca Information TechDocument1 paginăMca Information TechJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top Indian Advertising AgenciesDocument3 paginiTop Indian Advertising AgenciesGeorge D BonisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolution of Indian AdvertisingDocument5 paginiEvolution of Indian AdvertisingJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolution of Indian AdvertisingDocument5 paginiEvolution of Indian AdvertisingJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charts in ExcelDocument48 paginiCharts in ExcelJithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Int Trust 1225807540399009 9Document9 paginiInt Trust 1225807540399009 9Jithin KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Case Studies-Fobie Sociala Si DepresieDocument19 paginiClinical Case Studies-Fobie Sociala Si DepresieAgentia Ronet100% (1)

- Adjustment Disorders in Dsm5 Implications For Occupationalhealth SurveillanceDocument4 paginiAdjustment Disorders in Dsm5 Implications For Occupationalhealth SurveillancealinaneagoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disorganized SchizophreniaDocument11 paginiDisorganized SchizophreniaDesi Lestari NingsihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Texts in Counselling and Psychotherapy - Working With Eating Disorders - A Psychoanalytic ApproachDocument158 paginiBasic Texts in Counselling and Psychotherapy - Working With Eating Disorders - A Psychoanalytic ApproachHoàngKimNgânÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asian Journal of PsychiatryDocument3 paginiAsian Journal of PsychiatryFerina Mega SilviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Same-Sex MarriageDocument4 paginiSame-Sex MarriageReymart BaradilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yakeley 2018 Psychoanalysis in Modern Mental Health PracticeDocument8 paginiYakeley 2018 Psychoanalysis in Modern Mental Health PracticeJonathan RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sex, Honor, Murder A Psychology of Honor KillingDocument20 paginiSex, Honor, Murder A Psychology of Honor KillingcorinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAAS Consensus Report Residential Treatment 0413Document12 paginiSAAS Consensus Report Residential Treatment 0413DanaMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beck-Institute-Eating Disorder PresentationDocument28 paginiBeck-Institute-Eating Disorder PresentationninaanjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook of Neurodevelopmental and Genetic Disorders in AdultsDocument508 paginiHandbook of Neurodevelopmental and Genetic Disorders in AdultsrabiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colin Murray Parkes, Holly G. Prigerson - Bereavement - Studies of Grief in Adult Life (2009, Routledge) - Libgen - LiDocument368 paginiColin Murray Parkes, Holly G. Prigerson - Bereavement - Studies of Grief in Adult Life (2009, Routledge) - Libgen - Lijulie fitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auditory Hallucination: Audiological Perspective For Horror GamesDocument8 paginiAuditory Hallucination: Audiological Perspective For Horror GamesJuani RoldánÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kleptomania Thesis StatementDocument6 paginiKleptomania Thesis Statementangieloveseattle100% (2)

- Citizenship and Recovery: Two Intertwined Concepts For Civic-RecoveryDocument7 paginiCitizenship and Recovery: Two Intertwined Concepts For Civic-Recoveryantonio de diaÎncă nu există evaluări

- THE BIRD SEL-WPS OfficeDocument4 paginiTHE BIRD SEL-WPS OfficeJOYCE LORRAINE OSIMÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practitioner's Guide To BreathworkDocument18 paginiA Practitioner's Guide To BreathworkOctavio Uriel Garrido Lopez100% (1)

- Learning Disability: Lmsonlearning. ComDocument12 paginiLearning Disability: Lmsonlearning. ComSavio RebelloÎncă nu există evaluări

- In The Shadow of ProgressDocument11 paginiIn The Shadow of ProgressMatthew MicallefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Status ExamDocument75 paginiMental Status ExamJuan JaramilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Coercion in Mental Healthcare The Principle of Least Coercive CareDocument8 pagini4 Coercion in Mental Healthcare The Principle of Least Coercive CarePedro Y. LuyoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ian KerrDocument91 paginiIan Kerrnini345Încă nu există evaluări

- Checklist Example Completed Uk 2018Document14 paginiChecklist Example Completed Uk 2018Jo LiemÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument5 paginiWhat Is Autism Spectrum Disordervedaraju04Încă nu există evaluări

- Article On Being A Multidisciplinary TeamDocument22 paginiArticle On Being A Multidisciplinary TeamLizzie JanitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maldaptive Daydreaming - Written by Lana DhaouDocument2 paginiMaldaptive Daydreaming - Written by Lana DhaoulanadhaouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT-R) ReferencesDocument199 paginiHopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT-R) ReferencesJudit Subirana Mirete0% (1)

- MNS Care For CHO & SN - Addressing Stigma and DiscriminationDocument21 paginiMNS Care For CHO & SN - Addressing Stigma and DiscriminationSawanki And CoÎncă nu există evaluări