Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Corona Virus

Încărcat de

venkatgupthaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Corona Virus

Încărcat de

venkatgupthaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Coronavirus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

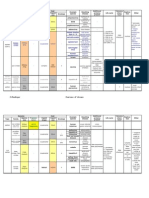

Jump to: navigation, search Coronavirus

Virus classification Group IV

((+)ssRNA)

Group:

Order: Family: Subfamily:

Nidovirales Coronaviridae Coronavirinae Genus

Alphacoronavirus Betacoronavirus Gammacoronavirus Coronaviruses are species in the genera of virus belonging to the subfamily Coronavirinae in the family Coronaviridae.[1][2] Coronaviruses are enveloped viruses with a positive-sense RNA genome and with a nucleocapsid of helical symmetry. The genomic size of coronaviruses ranges from approximately 26 to 32 kilobases, extraordinarily large for an RNA virus. The name "coronavirus" is derived from the Latin corona, meaning crown or halo, and refers to the characteristic appearance of virions under electron microscopy (E.M.) with a fringe of large, bulbous surface projections creating an image reminiscent of the solar corona. This morphology is actually created by the viral spike (S) peplomers, which are proteins that populate the surface of the virus and determine host tropism. Coronaviruses are grouped in the order Nidovirales, named for the Latin nidus, meaning nest, as all viruses in this order produce a 3' co-terminal nested set of subgenomic mRNA's during infection.

Proteins that contribute to the overall structure of all coronaviruses are the spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N). In the specific case of the SARS coronavirus (see below), a defined receptor-binding domain on S mediates the attachment of the virus to its cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).[3] Some coronaviruses (specifically the members of Betacoronavirus subgroup A) also have a shorter spike-like protein called hemagglutinin esterase (HE).[1]

Contents

[hide]

1 Diseases of coronavirus 2 Replication 3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome 4 Recent discoveries of novel human coronaviruses o 4.1 Listing of human coronaviruses 5 Taxonomy 6 References 7 External links

[edit] Diseases of coronavirus

Coronaviruses primarily infect the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tract of mammals and birds. Four to five different currently known strains of coronaviruses infect humans. The most publicized human coronavirus, SARS-CoV which causes SARS, has a unique pathogenesis because it causes both upper and lower respiratory tract infections and can also cause gastroenteritis. Coronaviruses are believed to cause a significant percentage of all common colds and pneumonia in human adults. Coronaviruses cause colds and pneumonia in humans primarily in the winter and early spring seasons. The significance and economic impact of coronaviruses as causative agents of the common cold are hard to assess because, unlike rhinoviruses (another common cold virus), human coronaviruses are difficult to grow in the laboratory. In chickens, the Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), a Coronavirus, targets not only the respiratory tract but also the uro-genital tract. The virus can spread to different organs throughout the chicken. Coronaviruses also cause a range of diseases in farm animals and domesticated pets, some of which can be serious and are a threat to the farming industry. Economically significant coronaviruses of farm animals include porcine coronavirus (transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus, TGE) and bovine coronavirus, which both result in diarrhea in young animals. Feline Coronavirus: 2 forms, Feline enteric coronavirus is a pathogen of minor clinical significance, but spontaneous mutation of this virus can result in feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a disease associated with high mortality. There are two types of canine coronavirus (CCoV), one that causes mild gastrointestinal disease and one that has been found to cause respiratory disease. Mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) is a coronavirus that causes an epidemic murine illness with high mortality, especially among colonies of laboratory mice. Prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV, MHV had been the best-studied coronavirus both in vivo and in

vitro as well as at the molecular level. Some strains of MHV cause a progressive demyelinating encephalitis in mice which has been used as a murine model for multiple sclerosis. Significant research efforts have been focused on elucidating the viral pathogenesis of these animal coronaviruses, especially by virologists interested in veterinary and zoonotic diseases.

[edit] Replication

The infection cycle of coronavirus Replication of Coronavirus begins with entry to the cell which takes place in the cytoplasm in a membrane-protected microenvironment. Upon entry to the cell the virus particle is uncoated and the RNA genome is deposited into the cytoplasm. The Coronavirus genome has a 5 methylated cap and a 3polyadenylated tail. This also allows the RNA to attach to ribosomes for translation. Coronaviruses also have a protein known as a replicase encoded in its genome which allows the RNA viral genome to be transcribed into new RNA copies using the host cells machinery. The replicase is the first protein to be made as once the gene encoding the replicase is translated the translation is stopped by a stop codon. This is known as a nested transcript, where the transcript only encodes one gene- it is monocistronic. The RNA genome is replicated and a long polyprotein is formed, where all of the proteins are attached. Coronaviruses have a non-structural protein called a protease which is able to separate the proteins in the chain. This is a form of genetic economy for the virus allowing it to encode the most amounts of genes in a small amount of nucleotides. Coronavirus transcription involves a discontinuous RNA synthesis (template switch) during the extension of a negative copy of the subgenomic mRNAs. Basepairing during transcription is a requirement. Coronavirus N protein is required for coronavirus RNA synthesis, and has RNA chaperone activity that may be involved in template switch. Both viral and cellular proteins are required for replication and transcription. Coronaviruses initiate translation by cap-dependent and cap-independent mechanisms. Cell macromolecular synthesis may be controlled after Coronavirus infection by locating some virus proteins in the host cell nucleus. Infection by different coronaviruses cause in the host alteration in the transcription and translation patterns, in the cell cycle, the cytoskeleton, apoptosis and coagulation pathways, inflammation, and immune and stress responses.[4]

[edit] Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Main article: Severe acute respiratory syndrome In 2003, following the outbreak of Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) which had begun the prior year in Asia, and secondary cases elsewhere in the world, the World Health Organization issued a press release stating that a novel coronavirus identified by a number of laboratories was the causative agent for SARS. The virus was officially named the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV). The SARS epidemic resulted in over 8000 infections, about 10% of which resulted in death.[3] X-ray crystallography studies performed at the Advanced Light Source of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have begun to give hope of a vaccine against the disease "since [the spike protein] appears to be recognized by the immune system of the host."[5]

[edit] Recent discoveries of novel human coronaviruses

Following the high-profile publicity of SARS outbreaks, there has been a renewed interest in coronaviruses in the field of virology. For many years, scientists knew only about the existence of two human coronaviruses (HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43). The discovery of SARS-CoV added another human coronavirus to the list. By the end of 2004, three independent research labs reported the discovery of a fourth human coronavirus. It has been named NL63, NL or the New Haven coronavirus by the different research groups.[6] The naming of this fourth coronavirus is still a controversial issue, because the three labs are still battling over who actually discovered the virus first and hence earns the right to name the virus. Early in 2005, a research team at the University of Hong Kong reported finding a fifth human coronavirus in two pneumonia patients, and subsequently named it HKU1. In September 2012, what is believed to be a new type of coronavirus, tentatively referred to as Novel Coronavirus 2012,[7] being similar to SARS (but still apart from it, and also different from the common cold-causing coronavirus) was discovered in Qatar and Saudi Arabia.[8] The World Health Organisation has issued a global alert accordingly [9] and issued an interim case definition to help countries strengthen health protection measures against the new virus. [10] The WHO update on 28 September 2012 said that the virus did not seem to transmit easily from person to person.[11] Another coronavirus has been identified from a human with pneumonia and renal failure.[12] This virus - HCoV-EMC/2012 - is most closely related to Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4 (BtCoV-HKU4) and Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 (BtCoV-HKU5), which prototype two species in lineage C of the genus Betacoronavirus.

[edit] Listing of human coronaviruses

HCoV-229E HCoV-OC43 SARS-CoV NL63/NL/New Haven coronavirus HKU1-CoV Novel coronavirus 2012 HCoV-EMC

[edit] Taxonomy

Genus: Alphacoronavirus; type species: Alphacoronavirus 1 o Species: Alpaca coronavirus,Alphacoronavirus 1, Human coronavirus 229E, Human Coronavirus NL63, Miniopterus Bat coronavirus 1, Miniopterus Bat coronavirus HKU8, Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, Rhinolophus Bat coronavirus HKU2, Scotophilus Bat coronavirus 512 Genus Betacoronavirus; type species: Murine coronavirus o Species: Betacoronavirus 1, Human coronavirus HKU1, Murine coronavirus, Pipistrellus Bat coronavirus HKU5, Rousettus Bat coronavirus HKU9, Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, Tylonycteris Bat coronavirus HKU4 Genus Gammacoronavirus; type species: Avian coronavirus o Species: Avian coronavirus, Beluga whale coronavirus SW1

A fourth genus Deltacoronavirus which includes BuCoV HKU11, ThCoV HKU12 and MunCoV HKU13 has also been proposed but has not yet been ratified by the ICTV.

[edit] References

1. ^ a b de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric R, Enjuanes L, Gorbalenya AE, Holmes KV, Perlman S, Poon L, Rottier PJM, Talbot PJ, Woo PCY, Ziebuhr J (2011). "Family Coronaviridae". In: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. AMQ King, E Lefkowitz, MJ Adams, and EB Carstens (Eds), Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 806-828. ISBN 978-0-12-384684-6.[page needed] 2. ^ "ICTV 2009 MASTER SPECIES LIST VERSION 4". 20 March 2010. http://talk.ictvonline.org/cfsfilesystemfile.ashx/__key/CommunityServer.Components.PostAttachments/00.00.00.12.31/I CTV_2D00_Master_2D00_Species_2D00_List_2D00_2009_5F00_v4.xls[dead link] 3. ^ a b Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC (September 2005). "Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor". Science 309 (5742): 18648. doi:10.1126/science.1116480. PMID 16166518. 4. ^ Enjuanes (2008). "Coronavirus Replication and Interaction with Host". Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.[page needed] 5. ^ "Learning How SARS Spikes Its Quarry". Press Release PR-HHMI-05-4. Chevy Chase, MD: Howard Hughes Medical Institute. http://www.lightsources.org/cms/? pid=1000828. Retrieved September 16, 2005. 6. ^ van der Hoek L (April 2004). "Identification of a new human coronavirus". Nature Medicine 10 (4): 36873. doi:10.1038/nm1024. PMID 15034574. 7. ^ Doucleef, Michaeleen (26 September 2012). "Scientists Go Deep On Genes Of SARS-Like Virus". Associated Press. http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/09/25/161770135/scientists-go-deep-on-genes-of-sarslike-virus. Retrieved 27 September 2012. 8. ^ http://thechart.blogs.cnn.com/2012/09/24/new-sars-like-virus-poses-medicalmystery/?hpt=he_c2 9. ^ http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2012/09/2012924182013530585.html 10. ^ "Novel coronavirus infection - update". http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/novel-coronavirus-infection.html. Retrieved 26 September 2012. 11. ^ http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/09/28/us-virus-whoidUSBRE88R0F220120928

12. ^ van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C, Bestebroer TM, Raj VS, Zaki AM, Osterhaus AD, Haagmans BL, Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ, Fouchier RA (2012) Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio 3(6). pii: e00473-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00473-12

[edit] External links

Laude H, Rasschaert D, Delmas B, Godet M, Gelfi J, Charley B (June 1990). "Molecular biology of transmissible gastroenteritis virus". Veterinary Microbiology 23 (14): 14754. doi:10.1016/0378-1135(90)90144-K. PMID 2169670. Sola I, Alonso S, Ziga S, Balasch M, Plana-Durn J, Enjuanes L (April 2003). "Engineering the transmissible gastroenteritis virus genome as an expression vector inducing lactogenic immunity". Journal of Virology 77 (7): 435769. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.7.4357-4369.2003. PMC 150661. PMID 12634392. http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12634392. Tajima M (1970). "Morphology of transmissible gastroenteritis virus of pigs. A possible member of coronaviruses. Brief report". Archiv Fr Die Gesamte Virusforschung 29 (1): 1058. doi:10.1007/BF01253886. PMID 4195092. Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Coronaviridae German Research Foundation (Coronavirus Consortium) [show]

v t e

Common cold

M: RES

anat (n, x, l, c)/phys/devp

noco (c, p)/cong/tumr, sysi/epon, injr [show]

proc, drug (R1/2/3/5/6/7)

v t e

Infectious diseases Viral systemic diseases (A80B34, 042079)

DNA virus JCV Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy RNA virus MeV Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis LCV Encephalitis/ meningitis Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Arbovirus encephalitis Orthomyxoviridae (probable) Encephalitis lethargica RV Rabies Chandipura virus Herpesviral meningitis Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II

Poliovirus

o

Poliomyelitis Post-polio syndrome

Myelitis

HTLV-I

o

Tropical spastic paraparesis

Cytomegalovirus

o

Cytomegalovirus retinitis

Eye

HSV

o

Herpetic keratitis

Epstein-Barr virus

IV: SARS coronavirus

o

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

V: Orthomyxoviridae: Influenzavirus A/B/C

o

Influenza/Avian influenza

RNA virus

V, Paramyxovirus: Human parainfluenza viruses

o

Parainfluenza

RSV hMPV

MuV

o

Mumps

Oropharynx/Esophagus

Cytomegalovirus

o

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis

DNA virus Adenovirus Adenovirus infection Gastroenteritis/ RNA virus diarrhea Rotavirus Norovirus Astrovirus Coronavirus DNA virus HBV (B) Hepatitis RNA virus CBV HAV (A)

HCV (C) HDV (D) HEV (E) HGV (G) Pancreatitis

CBV

cutn/syst (hppv/hiva, drug (dnaa, rnaa, rtva, infl/zost/zoon)/epon vacc) Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Coronavirus&oldid=540091550" Categories:

M: VIR

virs(prot)/clss

Nidovirales Animal virology

Hidden categories:

Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from February 2012 All articles with dead external links Articles with dead external links from June 2010 Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from September 2010 Articles with 'species' microformats

Navigation menu

Personal tools

Create account Log in

Namespaces

Article Talk

Variants Views

Read Edit View history

Actions Search

Navigation

Main page Contents Featured content Current events Random article Donate to Wikipedia

Interaction

Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Contact Wikipedia

Toolbox

What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Page information Cite this page Add your feedback View feedback

Print/export

Create a book Download as PDF Printable version

Languages

Catal Dansk Deutsch Espaol

Franais Bahasa Indonesia Italiano Nederlands Polski Portugus Suomi Svenska Edit links This page was last modified on 24 February 2013 at 16:17. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of Use for details. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Contact us Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Mobile view

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Sri Sri Sik Shasta KamDocument2 paginiSri Sri Sik Shasta KamvenkatgupthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translation: Jaya Sri-Krishna-Chaitanya Prabhu Nityananda Sri-Adwaita Gadadhara Shrivasadi-Gaura-Bhakta-VrindaDocument1 paginăTranslation: Jaya Sri-Krishna-Chaitanya Prabhu Nityananda Sri-Adwaita Gadadhara Shrivasadi-Gaura-Bhakta-VrindavenkatgupthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krishna BagavanDocument1 paginăKrishna BagavanvenkatgupthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lord KrishnaDocument1 paginăLord KrishnavenkatgupthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatomic Therapy English PDFDocument339 paginiAnatomic Therapy English PDFBabou Parassouraman100% (3)

- Anatomic Therapy Tamil PDF BookDocument320 paginiAnatomic Therapy Tamil PDF BookAthimoolam SubramaniyamÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Make Bootable USBDocument16 paginiHow To Make Bootable USBvenkatgupthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- AnlisisdegenmicacomparativadelvirusSARSalSARS CoV 2Document14 paginiAnlisisdegenmicacomparativadelvirusSARSalSARS CoV 2Blanca de Uña MartínÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cauliflower Mosaic VirusDocument2 paginiCauliflower Mosaic VirusMohan KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virology TableDocument10 paginiVirology TablekevinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Base de Datos para Articulos KarymeDocument26 paginiBase de Datos para Articulos Karymekaryme cabrera mironÎncă nu există evaluări

- FlubioDocument6 paginiFlubiosaidaa hasanahÎncă nu există evaluări

- PoxviridaeDocument2 paginiPoxviridaeAyioKunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analisis de Datos ExploratoriosDocument20 paginiAnalisis de Datos ExploratoriosDavid SuquilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 VirologiDocument32 pagini2 VirologiVanesa MuntuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ICTV Master Species List 2020.v1Document44 paginiICTV Master Species List 2020.v1Timothy GuintuÎncă nu există evaluări

- MGY378H1 S Microbiology Ii - Viruses January - April 2019Document4 paginiMGY378H1 S Microbiology Ii - Viruses January - April 2019random8736Încă nu există evaluări

- Veterinary Virology PDFDocument275 paginiVeterinary Virology PDFSam Bot100% (5)

- Virus TableDocument3 paginiVirus TableFrozenManÎncă nu există evaluări

- USMLE - VirusesDocument120 paginiUSMLE - Viruseszeal7777100% (1)

- ICTV Master Species List 2022 MSL38.v2Document1.654 paginiICTV Master Species List 2022 MSL38.v2Richard ThodéÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virus Patogenik: Hishamuddin Bin AhmadDocument26 paginiVirus Patogenik: Hishamuddin Bin AhmadShareall RazhiftÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ananthanarayan and Paniker S Textbook of Microbiology 10th Edition 2017 PDF RemovedDocument4 paginiAnanthanarayan and Paniker S Textbook of Microbiology 10th Edition 2017 PDF RemovedjenishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Virology: Introduction To BasicsDocument88 paginiMedical Virology: Introduction To BasicsSutapa PawarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paramyxoviridae EditedDocument30 paginiParamyxoviridae EditedstudymedicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viruses: Viruses Are Entities ThatDocument4 paginiViruses: Viruses Are Entities ThatMudit MisraÎncă nu există evaluări

- ViralZone Human VirusesDocument22 paginiViralZone Human VirusesFalio HarenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise12 PDFDocument17 paginiExercise12 PDFHayna RoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic VirologyDocument45 paginiBasic VirologyMatahun Dyah Maha RaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- PicornavirusDocument23 paginiPicornavirusMj BrionesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iridoviruses: Taxonomy Morphology Genome Replication Gene Expression PathogenesisDocument11 paginiIridoviruses: Taxonomy Morphology Genome Replication Gene Expression PathogenesisZeeham EscalonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virkon S EFICACITATEDocument12 paginiVirkon S EFICACITATEIuginnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arboviruses: R.Varidianto Yudo T., Dr.,MkesDocument19 paginiArboviruses: R.Varidianto Yudo T., Dr.,MkesalbertmogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virology TableDocument6 paginiVirology TablejeffdelacruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagnostic MycologyDocument5 paginiDiagnostic MycologyEarl de JesusÎncă nu există evaluări

- BunyaviridaeDocument12 paginiBunyaviridaeRia AlcantaraÎncă nu există evaluări