Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Mindreading and Empathy As Predictors of Prosocial Behavior

Încărcat de

user55246Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Mindreading and Empathy As Predictors of Prosocial Behavior

Încărcat de

user55246Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

351

MINDREADING AND EMPATHY AS PREDICTORS OF PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR

Vladimra AVOJOV, Zuzana BELOVIOV, Miroslav SIROTA Institute of Experimental Psychology, Slovak Academy of Sciences Dbravsk cesta 9, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovak Republic E-mail: vladimira.cavojova@savba.sk, zuzana.belovicova@savba.sk, miroslav.sirota@savba.sk

Abstract: Social understanding is usually conceptualized as consisting of understanding emotions (i.e., empathy) and understanding the others mental states (i.e., theory of mind or mindreading). Both these facets of social understanding are hypothesized to be related to prosocial orientation. The purpose of the presented study is, therefore, to examine whether theory of mind or empathy is the stronger predictor of prosocial orientation. As a secondary aim, we also explored the question of gender differences as an important differentiating factor in both theory of mind and empathy. 197 preadolescents aged 11 to 15 yrs. participated in the study. Participants filled out two tests of theory of mind skills, three empathy questionnaires and the prosocial orientation was determined by peer-nominated questionnaire. The results corroborated the idea that the higher the social understanding, the higher the prosocial orientation. Moreover, theory of mind predicted prosocial behavior better than empathy. Girls outperformed boys in both empathy and mindreading measures. Theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed. Key words: social understanding, theory of mind, empathy, prosocial behavior

INTRODUCTION Social understanding is a core ability for successful living among any group whether it is a group of hunters and gatherers, a working team or a group of teenagers. Early social understanding is believed to have predictive links to later social understanding and behavior. Individual differences in the abilities of social understanding have been observed since early childhood. Children

This research was supported, in part, by Grant Agency VEGA (Grant No. 1/0541/09). Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Vladimra avojov.

better in social understanding are believed to have more quality friendships, better ability to resolve conflicts and better adjustment in school (Hughes, 2011). Traditionally, it is believed that social understanding is related to many other concepts, such as moral reasoning, self-understanding and prosocial behavior (Bosacki, 2003). Most often two facets of social understanding have been studied: understanding of others beliefs and understanding of others emotions. Typically, understanding of emotions is seen as a core component of empathy and understanding of others beliefs (predominantly false) as a core component of mindreading (theory of mind). Mindreading usually relates to the ability to infer and attribute mental states, contents

352

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

and processes of thoughts to other people independently on our own mental states, contents and processes of thoughts. Paal and Bereczkei (2007) add to mindreading understanding desires, concepts, intentions and emotions. This is what connects mindreading with empathy, or at least it poses the questions about their different roles in social understanding. According to Doherty (2009) understanding emotions as motivator of behavior is similar to understanding beliefs. However, sophisticated understanding of emotions requires us to realize that emotions can be based on beliefs regardless on whether my desires were satisfied, if I believe they were, I am happy. In traditional view, empathy concerned only dealing with emotion responses and was often confused with sympathy for others in distress. However, recently it is recognized that empathy consists of affective as well as cognitive components (Andrew, Cooke, Muncer, 2008; Davis, 1983; Eisenberg, 2000; Paal, Bereczkei, 2007; Smith, 2006; and others) and we can empathize not only with a person in distress but also with a joyful person (which sometimes seems even harder). Within this approach to empathy, some authors implicitly or even explicitly identify cognitive aspect of empathy with mindreading (e.g., DAmbrosio et al., 2009) or use these terms as synonyms (e.g., Smith, 2006). Although empathy and mindreading should be distinguished, understanding others mental and emotional states shares some common ground, therefore, it is reasonable to expect correlations between these two concepts, as we do in our study. There is no straightforward relationship between mindreading and empathy and prosocial behavior. Studies (Ford, 1982; Pellegrini, 1985) found positive relationships

between social-cognitive processes, such as conceptual role-taking (usually considered as a component of mindreading), empathic sensitivity and person perception, teacher or peer ratings of positive social behavior and peer acceptance. However, these studies do not refer to mindreading directly, although their research paradigms bear some similarities with mindreading studies (Bosacki, Astington, 1999). For instance, Dekovic and Gerris (1994) found a significant association between childrens socialcognitive abilities (e.g., affective perspective-taking, prosocial moral reasoning) and their sociometric status, but this relation appeared to be mediated by prosocial behavior. Such findings highlight the potential importance and complexity of exploring the relations between childrens social-cognitive understanding and their social functioning (Repacholi et al., 2003). There is still inconclusive evidence of a relationship between mindreading (understanding of mental and intentional states of others), empathy (understanding of emotions of others) and prosocial orientation. That is why we are exploring the question whether social understanding will lead to pronounced prosocial orientation and whether it will result in higher popularity and acceptance by peer group reflected in the number of friends a person has. We expect that adolescents with better ability to infer mental and emotional states of others (as identified by mindreading and empathy measures) have more friends than their counterparts scoring lower in these measures. Because both empathy and mindreading are believed to be connected to the quality and quantity of friendships, we want to explore which one of them is a stronger predictor.

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

353

Walker (2005) criticizes studies of individual differences in mindreading for not taking into account the issue of gender. Yet, gender differences exist in social-cognitive functioning and they can play significant role in social life. Also, studies using traditional methods of measuring empathy (questionnaires, either self-reported or assessed by third person) usually confirm dominance of females in measures of empathy and understanding others mental states (Albiero et al., 2009; Baron-Cohen, 1997; DAmbrosio et al., 2009; Jolliffe, Farrington, 2006). Higher performance of girls in empathy measures is sometimes considered a validation factor (Albiero et al., 2009; DAmbrosio et al., 2009; Jolliffe, Farrington, 2006). Because we are using traditional measures of empathy, as well as some advanced tests of theory of mind, we want to verify this assumption as well. To summarise the general aim of this study, we want to explore these two issues: a) whether prosocial orientation is predicted more strongly by empathy or mindreading skills; and b) whether gender plays a differentiating role in empathy and mindreading. METHODS Participants Sample of 197 pre-adolescents took part in the study on a voluntary basis. Participants were recruited from three primary schools, two in Nitra and one in ilina (both in Slovakia). Participants mean age was 13.28 (SD = 1.50) and ranged from 11 to 15 years. A gender ratio was approximately equal, with slightly more boys represented in our sample (101 boys: 96 girls).

Measures Mindreading skills were measured by Imposing Memory Task (Kinderman, Dunbar, Bentall, 1998) and Awkward Moments Test (Heavey et al., 2000) as a more ecologically valid measure of mindreading performance. Empathy was measured by three questionnaires which focused on different aspects of empathy: Empathy Scale Items (Caruso, Mayer, 1998), Basic Empathy Scale (Jolliffe, Farrington, 2006) and Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1980). Details of the measures used are provided in the following sections. Social status of the individual, prosocial orientation and ability to win friends within and outside the school setting was determined by peer-nominated questionnaire. Imposing Memory Task The IMT featured a series of five stories that were read aloud to the participants at the same time as being presented via computer projection. Four of these stories involved complex social situations that required listeners to understand various intentions and perspectives of the actors (such as complicated love affairs or an attempt to deceive the boss to get a pay rise). The fifth story involved control as it depicted only one actor and a chain of causal events (the old man who burnt himself in his sleep with a cigarette). The children answered memory questions presented in a booklet and they had to choose between one correct and one incorrect option. The questions either concerned mindreading elements in the stories (the expectations or beliefs of participants) or were memory questions. Both types of questions involved a number of lev-

354

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

els of complexity, e.g. the first-order mindreading questions related to what the actor thought; the second-order mindreading questions related to what actor thought that another person thought; the third-order ones related to what the actor thought that the other person thought about another person or the actor him/herself and so on. The highest order of questions was the fifth order. Example of the story and related questions are in Appendix 1. The total score for all stories then ranged from 0, indicating low ability to store and infer information about other persons mental states, to 40 points indicating an excellent abilityto store and infer information about other persons mental states. Awkward Moments Test The AMT, on the other hand, was created as a more ecologically valid measure of mindreading, featuring 6 short films that introduced characters in awkward or socially embarrassing situations. The clips were created by a similar procedure to the one used by the original authors (Heavey et al., 2000), but from our own cultural background (short summaries of clips are available upon request from the corresponding author). Participants first watched each clip and then answered three questions: a) control question (memory and attention), b) emotion question (correct recognition of target characters emotion) and c) mindreading question (inferring the intention of the character). In the first two questions the participants could score either 1 (correct answer) or 0 (wrong answer). Answers to the mindreading question were subjected to content analysis and quality and elaborateness of the answers were evaluated. The scoring was based on Bosacki and Astington (1999) coding

scheme1. For a fully elaborated answer the participant was given 3 points; 2 points were given for a simple answer including the mental state of an actor, 1 point was given for mere situational descriptions and no points were given for no answer or tangential responses. Empathy Scale Items The ESI is the most widely used empathy measure in Slovakia, therefore we have chosen it as the first comparison measure of empathy. Full version consists of 30 items that reflect 6 factors (Suffering, Positive sharing, Responsive crying, Emotional attention, Feel for others, and Emotional contagion), all of which represent only the affective component of empathy. Basic Empathy Scale The BES consists of 20 items, 9 measuring cognitive empathy, 11 measuring affective empathy. Responses were made on a fivepoint Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The Slovak adaptation of the measure has been validized (avojov, Beloviov, Sirota, manuscript). A minimum of 9 and 11 points

Compared to the coding scheme of the authors of this test (Heavey et al., 2 000) ou r coding scheme was more sensitive to pre-adolescent age, because it represented levels of interpersonal understanding based on increasing complexity of responses. For example, the coding reflected the childs ability to move from obvious behavioral characterization of a situation (response to the intent question) to the interaction of several different abstract psychological concepts and the integration of multiple and sometimes paradoxical perspectives (Bosacki, Astington, 1999).

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

355

indicated low cognitive and affective empathy, respectively and a maximum of 45 and 55 points indicated high cognitive and affective empathy, respectively. Interpersonal Reactivity Index The IRI is an empathy measure, which is the most widely used measure in studies of empathy, because it measures 4 theoretical factors: Perspective Taking (PT), Fantasy (F), Empathic Concern (EC) and Personal Distress (PD). It consists of 28 items and all responses are made on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), with minimum of 28 points indicating low overal empathy and maximum of 140 points indicating high overal empathy. Peer-Nominated Questionnaire

Procedure The procedure of data collection was divided into two separate sessions to avoid a fatigue effect of the participants. In the first session, the empathy questionnaires were administered in the participants own classroom by their teacher of ethics or school psychologist. All the questionnaires were presented bound together. Total time of administration was approximately one lesson (i.e., 45 minutes). The second session took place about one month later and it took another 45 minutes to administer two mindreading measures (IMT and AMT) and peer-nominated questionnaire concerning relationships in the classroom. The administration was done by two researchers unknown to the participants. RESULTS

For our study we modified questionnaire of social behavior used in the study of Grolu, van Lieshout, Haselger, and Scholte (2007). It adressed 3 aspects of social behavior: a) number of friends (within the class and outside of class), b) peer reported antisocial behavior (Which three of your classmates starts fights, disturbs and becomes angry quickly?), and c) peer reported prosocial behavior (Which three of your classmates offers help, likes to work with others, is the most favorite?). Score of nominations of each participant helped to determine the sociometric status of an individual, with these four variables: number of friends (self-reported), friend nominations (peernominated), pro-social orientation (peernominated 3 items, Cronbachs alpha = 0.583) and conduct problems (peer-nominated 3 items, Cronbachs alpha = 0.822).

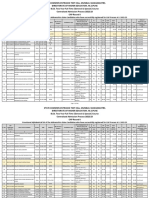

Mindreading and Empathy as Predictors of Prosociality and Friendliness In order to analyze indicators of empathy and mindreading as predictors of prosocial orientation and friendships, a multiple logistic regression analysis was employed with recoded outcome variables. The rationale for this analysis stemmed from skewed distribution of outcomes variables since a skewed distribution of these variables could be expected in our population as well. Firstly, we used median splits of outcome variables in the whole sample (Table 1) and then we used two extreme groups of participants defined as first and forth quartiles, i.e. those who received highest and lowest number of peer nominations (Table 2).

356

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

Table 1. Prediction models for the whole sample

DV Prosocial Antisocial Peer friends Friends 1 Model fit Hosmer & 9.3 4.1 7.8 3.8 Lemeshow (2, p) (.316) (.848) (.449) (.870) Cox & Snell (R2) .07 .08 .01 .06 Nagelkerke (R2) .09 .11 .01 .08 IV Empathy 0.99 0.98 1.00 0.99 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [0.98, 1.01] [0.97, 1.00] [0.99, 1.02] [0.97, 1.01] BES-ce 1.02 0.97 0.99 0.99 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [0.95, 1.09] [0.91, 1.04] [0.94, 1.06] [0.92, 1.06] IMT 1.09 1.01 0.90 1.11 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [0.99, 1.21] [0.81, 0.99] [0.92, 1.11] [1.00, 1.24] AMT 0.93 1.04 1.25 1.24 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [1.06, 1.48] [0.79, 1.09] [0.89, 1.21] [1.04, 1.49] Constant 0.20 .01 1052.27 0.03 (Exp(B)) Note: Outcome variables are defined as median split (dummy coded) Friends 2 8.1 (.428) .04 .05 1.00 [0.99, 1.02] 0.99 [0.92, 1.06] 1.07 [0.97, 1.19] 1.11 [0.93, 1.34] 0.03

Table 2. Prediction models for the extreme groups (N = 85)

DV Prosocial Antisocial N peer Friends 1 Friends 2 Model fit Hosmer & 2.3 5.8 10.4 7.5 4.4 Lemeshow (2, p) (.970) (.667) (.240) (.482) (.739) Cox & Snell (R2) .19 .14 .04 .08 .11 Nagelkerke (R2) .25 .18 .05 .11 .14 IV Emphaty 0.98 0.98 0.99 0.99 1.01 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [0.96, 1.01] [0.96, 1.00] [0.98, 1.02] [0.98, 1.01] [0.98, 1.03] Bes-ce 1.04 0.98 1.01 0.99 1.00 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [0.95, 1.15] [0.89, 1.07] [0.93, 1.11] [0.91, 1.09] [0.90, 1.11] IMT 1.02 1.26 0.85 1.20 1.24 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [1.06, 1.50] [0.73, 0.99] [0.89, 1.18] [1.03, 1.37] [1.03, 1.49] AMT 0.98 1.25 1.20 1.09 1.44 (Exp(B), 95% CI) [1.11, 1.87] [0.80, 1.21] [0.99, 1.58] [0.96, 1.49] [0.83, 1.43] Constant 0.10 .00 12687.95 0.01 0.00 (Exp(B)) Note: Outcome variables are defined by extreme groups defined as 1st and 4th quartils (dummy coded)

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

357

The results suggest that both IMT and AMT (mindreading measures) are stronger predictors of prosocial, as well as antisocial behavior, than empathy (either affective or cognitive). Those, who scored high in mindreading tests were considered by their peers to be more prosocially oriented and less inclined to display antisocial behavior in classroom. Moreover, those who scored high in mindreading tests reported significantly more friends inside and outside of classroom. Differentiating Role of Gender in Empathy and Mindreading As depicted in Table 3, girls scored higher than boys in all measures used to determine empathy and mindreading. These differences were statistically significant, as is shown in Table 3 by non-overlapping confidence intervals. Effect sizes expressed by Cohens d ranged from medium large for

CE BES, IMT and AMT scores to large for the rest of the scores. Based on differences found, hypothesis predicting higher performance of girls compared to boys in empathy and mindreading skills were confirmed. Subsequently, we examined correlations between two tests of mindreading and empathy questionnaires separately for girls and boys. The results showed that perspective taking measured by IRI has highest correlations with both mindreading tests in both boys and girls. We found more correlations between empathy and mindreading measures in girls than boys. DISCUSSION In this study we verified several assumptions. Firstly, we explored the question whether social understanding would lead to pronounced prosocial orientation (given by higher popularity and acceptance in peer group reflected in the number of friends a

Table 3. Differences between boys and girls in indicators of theory of mind and empathy

Boys Girls 95-% CI of Cohens Total M (SD) M (SD) difference d M (SD) CE BES 33.1 (5.1) 35.5 (4.6) -3.7; -0.9 0.49 34.3 (5.0) AE BES 30.9 (5.9) 37.3 (5.6) -8.0; -4.8 1.11 34.0 (6.6) Empathy Gen ESI 57.9 (11.4) 65.5 (10.7) -10.7; -4.5 0.69 61.6 (11.7) measures Cry ESI 6.8 (2.5) 9.1 (2.6) -3.0; -1.5 0.90 7.9 (2.8) PT IRI 51.4 (8.6) 58.2 (7.8) -9.1; -4.4 0.83 54.7 (8.9) IMT 32.7 (3.3) 34.3 (2.7) -2.5; -0.8 0.53 33.5 (3.1) ToM measures AMT 6.8 (2.2) 7.8 (1.5) -1.5; -0.4 0.53 7.3 (2.0) Note: n (boys) = 96, n (girls) = 101; CE BES = cognitive empathy measured by BES, AE BES = affective empathy measured by BES, Gen ESI = general empathy factor measured by ESI, Cry ESI = crying factor measured by ESI, PT IRI = perspective taking factor measured by IRI, IMT = total score in Imposing Memory Task, AMT = total score of intention questions in Awkward Moments Test

358

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

Table 4. Correlations between empathy and ToM measures in boys and girls

IMT TOT AMT TOT CE BES .183 .175 AE BES .135 .121 boys Gen_ESI .094 .267** Cry_ESI -.052 .038 PT_IRI .281** .244* ** CE BES .153 .333 AE BES .082 .222* girls Gen_ESI -.023 .224* Cry_ESI .088 -.023 PT_IRI .368** .212* Note: Nboys = 96, Ngirls = 101; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; CE BES = cognitive empathy measured by BES, AE BES = affective empathy measured by BES, Gen ESI = general empathy factor measured by ESI, Cry ESI = crying factor measured by ESI, PT IRI = perspective taking factor measured by IRI, IMT = total score in Imposing Memory Task, AMT = total score of intention questions in Awkward Moments Test

person has) and whether mindreading or empathy is the stronger predictor of social understanding. Then, we compared the performance of girls and boys in empathy and mindreading measures and verified the relationship between mindreading and empathy. Our main aim was to determine whether empathy or theory of mind is the stronger predictor of social behavior in preadolescence. Research findings concerning the relationships between social understanding abilities and social relations in preadolescents have been contradictory and inconclusive (Bosacki, Astington, 1999). Some of the social understanding components, such as empathic sensitivity and perspective-taking, have been found to be related to peer ratings of positive social behavior and peer acceptance (Ford, 1982; Pellegini, 1985). However, some other studies failed to find a relationship between various social under-

standing skills and social status (Rubin, 1972). Peer relationships are considered to be a more objective indicator of social functioning of children (Repacholi et al., 2003). There is a long history of research looking specifically at peer relationships as indices of childrens social functioning and there are also many methods used to measure them, such as self-report, parent and teacher ratings, peer nominations and observation. The results of our study tend to support the notion that social understanding is connected to preadolescent social behavior and their social status in classroom. Based on the results of our study, it seems that social understanding, as reflected in measures of theory of mind, leads to pronounced prosocial orientation and higher number of friends one thinks that one has, along with decreased display of antisocial behavior in classroom.

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

359

The ability to think about the intentions and beliefs of others can then be seen as a stronger predictor of prosocial orientation than empathy. However, it is necessary to point out that all measures of empathy were self-reported questionnaires and many studies have shown discrepancies between selfreported measures and measures of ones abilities evaluated by others. This was also shown by the current study, when we compared the number of friends in the classroom. Still, our results at least suggest that performance tests measuring actual skills are more reliable and objective than self-reported measures, especially in the case of young participants. Mindreading is considered the basis for human ability to deceive, cooperate, empathize and decode mental state by observing a persons body movements. Most empirical studies have focused on infants and young children or groups of individuals with hypothesized mindreading disorders (such as autism and schizophrenia), when determining the threshold of acquiring the theory of mind ability. We focused our attention on teenagers because it is crucial for them to develop social skills based on understanding of mental and emotional states of others, in order to survive in their social environment. However, it must be noted that it seems that there are two possibilities of dealing with well-developed empathy and theory of mind prosocial and antisocial. Not all helping behavior is motivated by empathy (Buck, Ginsburg , 1997), but rather by principalism (Abelson, Frey, Gregg, 2004), higher moral reasoning (Janssens, Dekovi, 1997), or sympathy (Eisenberg, Zhou, Koller, 2001). It has also been assumed that people better at inferring mental and emotional states of others (therefore

better at mindreading) can use this ability for selfish purposes (McIlwain, 2003; Shlien, 1997). Using mindreading for selfish and manipulative purposes is often connected with the study of Machiavellianism. According to McIlwain (2003), Machiavellianism and empathic understanding represent two types of individual differences in mindreading. Therefore, she assumed that between Machiavellianism and mindreading should exhibit a strong relationship and Machiavellists will differ in the degree of empathy. But she found no evidence for this assumption. Also, Paal and Bereczki (2007) explored the relationship between Machiavellianism, mindreading and helping behavior and they found a) strong negative relationship between Machiavellianism and social cooperative skills, b) relationship between cooperative tendency and level of mindreading and c) no significant correlation between mindreading and Machiavellianism. We are of the opinion that the relationship between mindreading, empathy social understanding and Machiavellianism can be the subject of further research. One of the related results of this study is that relationships between empathy and mindreading depend on gender. Many gender differences reported in the literature on social behavior and social cognition in preadolescence are in line with traditional gender-role stereotypes. In Bosacki and Astingtons review (1999), the majority of the studies report that: a) girls are rated as more socially competent and are perceived as more prosocial than boys, who are seen as more aggressive and b) girls score higher in social perspective-taking (considered a typical mindreading skill) and empathy than boys. However, other evidence shows (Ickes, 1997) that many of these traditional gender differ-

360

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

ences disappear when we use other measures than self-reported or teacher/parentreported questionnaires, which can reflect biases and role stereotypes of the evaluators. Better performance of girls in both empathy and mindreading measures can be interpreted both, as their naturally higher propensities in the field of social relationships and as a result as their more rapid mental and physical development in sensitive preadolescent and adolescent age. Therefore, it would beneficial to look for gender differences in adult participants as well. CONCLUSION The main aim of our study was to explore whether prosocial orientation is predicted more strongly by empathy or mindreading, as the two facets of social understanding; and whether gender plays a differentiating role in empathy and mindreading. The results indicated that mindreading, as reflected in the tasks used in our study, better predicted a willingness to cooperate and help others, as well as the number of friends a person reported having a behavior that comprised prosocial behavior in the classroom. It also predicted lower occurance of quarrels, fights and disturbing antisocial behavior in the classroom. The study also showed a dominant performance of girls in social understanding and revealed a different pattern of the relationship between empathy and mindreading skills in boys and girls. Consistent gender differences (e.g., Albiero et al., 2009; Baron-Cohen, 1997; DAmbrosio et al., 2009; Jolliffe, Farrington, 2006) in the abilities related to social understanding, such as mindreading and empathy, highlight the importance of a

differentiated approach to this topic based on the gender of the participants.

Received June 13, 2011

REFERENCES

ABELSON, R.P., FREY, K.P., GREGG, A.P., 2004, Experiments with People. Revelations from social psychology . London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. ALBIERO, P., MATRICARDI, G., SPELTRI, D., TOSO, D., 2009, The assessment of empathy in adolescence: A contribution to the Italian validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Journal of Adolescence , 32, 393-408. ANDREW, J., COOKE, M., MUNCER, S.J., 2008, The relationship between empathy and Machiavellianism: An alternative to empathizing systemizing theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1203-1211. BARON-COHEN, S., 1997, Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind . Cambridge: MIT Press. BOSACKI, S.L., 2003, Psychological pragmatics in preadolescents: Sociomoral understanding, self-worth, and school behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 32, 141-155. BOSACKI, S., ASTINGTON, J.W., 1999, Theory of Mind in preadolescence: Relations between social understanding and social competence. Social Development , 8, 237-255. BUCK, R., GINSBURG, B., 1997, Communicative genes and the evolution of empathy. In W. Ickes (Eds.), Empathic accuracy (pp. 17-43). New York: Guilford Press. CARUSO, D.R., MAYER, J.D., 1998, A measure of emotional empathy for adolescents and adults. Unpublished Manuscript. AVOJOV, V., BELOVIOV, Z., SIROTA, M., Manuscript, Validation of the Basic Empathy Scale in pre-adolescents in Slovakia. DAVIS, M.H., 1983, The effects of dispositional empathy on emotional reactions and helping: a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality, 51, 2. DAMBROSIO, F., OLIVIER, M., DIDON, D., BESCHE, C., 2009, The Basic Empathy Scale: A French validation of a measure of empathy in youth. Personality and Individual Differences , 46, 160-165.

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

361

DOHERTY, M.J., 2009, Theory of Mind: How children understand others thoughts and feelings. Hove: Psychology Press. EISENBERG, N., 2000, Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology , 51, 665-697. EISENBERG, N., ZHOU, Q., KOLLER, S., 2001, Brazilian adolescents prosocial moral judgement and behavior: Relations to sympathy, perspective taking, gender-role orientation, and demographic characteristics. Child Development , 72, 518-534. FORD, M., 1982, Social cognition and social competence in adolescence. Developmental Psychology , 18, 323-340. GROLU, B., VAN LIESHOUT, C.F.M., HASELGER, G.J.T., SCHOLTE, R.H.J., 2007, Similarity and complementarity of behavioral profiles of friendship types and types of friends. Journal of Research on Adolescence , 17, 357-386. HEAVEY, L., PHILLIPS, W., BARON-COHEN, S., RUTTER, M., 2000, The Awkward Moments Test: A naturalistic measure of social understanding in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 30, 225-236. HUGHES, C., 2011, Social understanding and social lives. From toddlerhood through to the transition to school. Hove: Psychology Press. ICKES, W., 1997, Empathic Accuracy . London: Guilford Press. JANSSENS, J.M.A.M., DEKOVI, M., 1997, Child rearing, prosocial moral reasoning, and prosocial behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development , 20, 509-527. JOLLIFFE, D., FARRINGTON, D.P., 2006, Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Journal of Adolescence , 29, 589-611. KINDERMAN, P., DUNBAR, R., BENTALL, R.P., 1998, Theory-of-mind deficits and causal at-

tributions. British Journal of Psychology , 89, 19120 4. McILWAIN, D., 2003, Bypassing empathy: A Machiavellian theory of mind and sneaky power. In: B. Repacholi, V. Slaughter (Eds.), Individual Differences in Theory of Mind (pp. 40-64). Hove: Psychology Press. PAAL, T., BERECZKEI, T., 2007, Adult theory of mind, cooperation, Machiavellianism: The effect of mindreading on social relations. Personality and Individual Differences , 43, 541-551. PELLEGRINI, D., 1985, Social cognition and competence in middle childhood. Child Development, 56, 253-264. REPACHOLI, B., SLAUGHTER, V., PRITCHARD, M., GIBBS, V., 2003, Theory of mind, Machiavellism, and social functioning in childhood. In: B. Repacholi, V. Slaughter (Eds.), Individual differences in theory of mind. Macquarie monographs in cognitive science (pp. 99-120). Hove, E. Sussex: Psychology Press. RUBIN, K., 1972, Relationship between egocentric communication and popularity among peers. Developmental Psychology , 7, 364. SHLIEN, J.M., 1997, Empathy in psychotherapy. Vital mechanism? Yes. Therapists conceit? All too often. By itself enough? No. In: P. Sanders (Eds.), To lead an honorable life. A collection of the work of John M. Shlien (pp. 63-80). Herefordshire: PCCS Books. SMITH, A., 2006, Cognitive empathy and emotional empathy in human behavior and evolution. The Psychological Record , 56, 3-21. WALKER, S., 2005, Gender differences in the relationship between young childrens peer-related social competence and individual differences in theory of mind. The Journal of Genetic Psychology , 3, 297-312.

APPENDIX 1

WHERES THE POST OFFICE? Sam wanted to find a Post Office so he could buy a Tax Disc for his car. He asked Henry if he could tell him where to get one. Henry told him that he thought there was a Post Office in Elm Street. When Sam got to Elm Street, he found it was closed. A notice on the door said that it had moved to new premises in Bold Street. So Sam went to Bold Street and found the new Post Office. When he got to the counter, he discovered that he had left his MOT certificate at home. He realized that without an MOT certificate, he could not get a Tax Disc, so he went home empty-handed.

Appendix 1 continues

362

STUDIA PSYCHOLOGICA, 53, 2011, 4

(Appendix 1 continued)

Please tick the correct answer to each question: 2. a) Henry thought Sam would find the Post Office in Elm Street b) Henry thought Sam would find the Post Office in Bold Street 6. a) Sam thought that Henry believed that Sam wanted to buy a Tax Disc b) Sam thought that Henry did not know that Sam wanted to buy a Tax Disc

TANIE MYSLE A EMPATIA AKO PREDIKTORY PROSOCILNEHO SPRVANIA

V. a v o j o v , Z. B e l o v i o v , M. S i r o t a Shrn: Socilne porozumenie sa sklad z chpania emci (t.j. empatie) a chpania duevnch stavov druhch ud (t.j. teria mysle). Predpoklad sa, e obe tieto strnky socilneho porozumenia svisia s prosocilnym sprvanm. Cieom predkladanej tdie je preto skma, i je silnejm prediktorom prosoci lneho sprva nia teria mysle a lebo empa tia . Druhotnm cieom bolo preskma otzku rodovch rozdielov a ko dleitho odliovacieho faktoru v terii mysle a empatii. tdie sa zastnilo 197 preadolescentov vo veku 11 a 15 rokov. Participanti vyplnili 2 testy schopnost terie mysle, 3 dotaznky na empatiu a prosocilne sprvanie sa zisovalo nominanm sociometrickm dotaznkom. Vsledky potvrdili predpoklad, e m vyie socilne porozumenie, tm sa astejie vyskytuje aj prosocilne sprvanie. Navye, teria mysle predikovala socilne porozumenie lepie ako empatia. Dieva t podali lep vk on vo vetkch testoch a dotaznkoch na teriu mysle a empatiu.

Copyright of Studia Psychologica is the property of Institute of Experimental Psychology, Slovak Academy of Science and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Managing Irregular Airport OperationsDocument12 paginiManaging Irregular Airport Operationsuser55246Încă nu există evaluări

- 83410861Document6 pagini83410861user55246Încă nu există evaluări

- 64495284Document19 pagini64495284user55246100% (1)

- Empathy and Theory of Mind in Offenders With Intellectual DisabilityDocument13 paginiEmpathy and Theory of Mind in Offenders With Intellectual Disabilityuser55246Încă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Alphabetic List (Maharashtra State) - Round 2Document994 paginiAlphabetic List (Maharashtra State) - Round 2Mysha ZiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accounting Theory ConstructionDocument8 paginiAccounting Theory Constructionandi TenriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chomsky, N. (1980) - Binding PDFDocument47 paginiChomsky, N. (1980) - Binding PDFZhi ChenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ucsp Tos First QuarterlyDocument8 paginiUcsp Tos First QuarterlyJuvelyn AbuganÎncă nu există evaluări

- SKOS: Simple Knowledge: Organization SystemDocument7 paginiSKOS: Simple Knowledge: Organization SystemMir JamalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maria Socorro Cancio (National Book Store)Document3 paginiMaria Socorro Cancio (National Book Store)Hadassah AllatisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mba Finance CourseworkDocument7 paginiMba Finance Courseworkbcrqs9hr100% (2)

- Essay WritingDocument18 paginiEssay Writing3kkkishore3Încă nu există evaluări

- Predictive Maintenance Ebook All ChaptersDocument58 paginiPredictive Maintenance Ebook All ChaptersMohamed taha EL M'HAMDIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ma. Georgina Belen A. Guevara 27 San Mateo St. Kapitolyo, Pasig City 576-4687 / 0927-317-8221Document4 paginiMa. Georgina Belen A. Guevara 27 San Mateo St. Kapitolyo, Pasig City 576-4687 / 0927-317-8221Colette Marie PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- R. Bieringer, D. Kurek-Chomycz, E. Nathan 2 Corinthians A Bibliography Biblical Tools and Studies, Vol 5 2008 PDFDocument367 paginiR. Bieringer, D. Kurek-Chomycz, E. Nathan 2 Corinthians A Bibliography Biblical Tools and Studies, Vol 5 2008 PDFManticora Caelestis100% (1)

- Study Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Document18 paginiStudy Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Brayhan Huaman BerruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islamic CultureDocument14 paginiIslamic CultureSajeela JamilÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRM - Case StudiesDocument30 paginiCRM - Case StudiesRevathi100% (1)

- Buzz Session Rubrics 2Document8 paginiBuzz Session Rubrics 2Vincent Jdrin67% (3)

- Abre VbsDocument1 paginăAbre Vbsdisse_detiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education and Technology in IndiaDocument23 paginiEducation and Technology in IndiaNayana Karia100% (1)

- Porter's DiamondDocument3 paginiPorter's DiamondNgọc DiệpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education and Theatres 2019Document325 paginiEducation and Theatres 2019Alex RossiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020 Ensemble Program Audition: Double BassDocument6 pagini2020 Ensemble Program Audition: Double BassCarlos IzquwirdoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment Submitted by Maryam Mumtaz Submitted To Mam Tyabba NoreenDocument3 paginiAssignment Submitted by Maryam Mumtaz Submitted To Mam Tyabba NoreenShamOo MaLikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Government of Jammu and Kashmir,: Services Selection Board, Zum Zum Building Rambagh, Srinagar (WWW - Jkssb.nic - In)Document161 paginiGovernment of Jammu and Kashmir,: Services Selection Board, Zum Zum Building Rambagh, Srinagar (WWW - Jkssb.nic - In)Stage StageÎncă nu există evaluări

- ### TIET (Counselling Report)Document2 pagini### TIET (Counselling Report)Piyuesh GoyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grammar MTT3Document2 paginiGrammar MTT3Cẩm Ly NguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- EV ChargingDocument20 paginiEV Chargingvijaya karthegha.RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 5 Sports CoachingDocument12 paginiUnit 5 Sports CoachingCHR1555100% (1)

- Music Education Research: To Cite This Article: Pamela Burnard (2000) : How Children Ascribe Meaning ToDocument18 paginiMusic Education Research: To Cite This Article: Pamela Burnard (2000) : How Children Ascribe Meaning Togoni56509100% (1)

- v1 AC7163 AutoCAD Certified Associate HandoutDocument11 paginiv1 AC7163 AutoCAD Certified Associate HandoutaudioxtraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Researchhh 3B 1Document17 paginiResearchhh 3B 1Gerland Gregorio EsmedinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formative 1 - Ans KeyDocument47 paginiFormative 1 - Ans KeyDhine Dhine ArguellesÎncă nu există evaluări