Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Government Response To Modifying Protective Order

Încărcat de

C FurmanTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Government Response To Modifying Protective Order

Încărcat de

C FurmanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 1 of 14

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA | | v. | | AARON SWARTZ, | | Defendant | |

CRIMINAL No. 11-CR-10260-NMG

RESPONSE OF THE UNITED STATES TO THE MOTION TO MODIFY PROTECTIVE ORDER The United States hereby responds to the Motion to Modify the Protective Order (Motion) filed by the estate of the Defendant Aaron Swartz (the Estate) 1 on March 15, 2013. The United States generally agrees that the Protective Order (Dkt. 28) should be modified to permit disclosure of certain materials to Congress and the public. As discussed in more detail below, disclosure of the materials should nevertheless be subject to the redactions the United States has proposed and with which the movant disagrees. In addition, the United States requests that the Court provide those potentially affected by such a disclosure the opportunity to review and comment upon, and, if necessary, object to, the disclosure of the redacted materials prior to any release. BACKGROUND On July 14, 2011, a grand jury returned an Indictment against the defendant in this matter. On August 12, 2011, pursuant to Rule 16 and Local Rule 116.1(C) and 116.2, the United States made its automatic disclosures. In its automatic disclosure letter of August 12, 2011, the The United States addresses later in this response the question whether the Estate has standing to obtain the relief sought in the Motion.

1

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 2 of 14

United States informed the defendant that it would not make certain discovery materials available until after a protective order was entered. See Declaration of Michael Pineault in Support of the Motion (Pineault Decl.) at 9, Ex. C at p.2 (we will need to arrange a protective order with you before inspection.). As the United States set forth in the automatic disclosure letter, the discovery materials it would be providing the defendant contained potentially sensitive, confidential, and proprietary communications, documents and records obtained from victims JSTOR and MIT, including discussions of the victims computer systems and security measures. [Id.]. On November 30, 2011, the United States, Mr. Swartz and his attorney stipulated to, and the magistrate judge entered, the Protective Order. [See Dkt. 28 at 6]. The Protective Order applies to all discovery materials provided by either party. [Dkt. 28 at 1]. The discovery materials include potentially sensitive, confidential and proprietary communications, documents and records obtained from JSTOR and MIT, inter alia. [Dkt. 28 at 1]. The Protective Order limits the use of the materials exchanged exclusively to litigate this case. [Dkt. 28 at 3]. On January 11, 2013, the defendant committed suicide. On January 14, 2013, the United States filed a dismissal of this case, and the Court entered an order of dismissal that same day. [Dkt. 105, 106]. On February 7, 2013, estate counsel (Michael J. Pineault) notified the United States of a Congressional request for access to discovery materials and asked the United States whether it would assent to a modification of the Protective Order. [Declaration of Jack W. Pirozzolo in Support of the United States Response to the Motion (Pirozzolo Decl.) 2]. The United States and estate counsel then engaged in a series of discussions pursuant to the meet and confer requirements of Local Rule 7.1(A)(2) in order to narrow the areas of disagreement. 2

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 3 of 14

During the course of those discussions, the United States and estate counsel were able to reach an agreement on most, but not all, issues related to a possible modification of the protective order. The United States and estate counsel agreed to the following: the Protective Order should be modified to provide the discovery materials, subject to certain limitations, to Congress; any modification of the Protective Order should nevertheless not permit disclosure of certain materials, including (a) transcripts of grand jury testimony, (b) materials concerning immunity for grand jury witnesses, (c) a particular set of JSTOR articles, (d) any computer code that was used or intended to be used to download articles from JSTOR, and (e) criminal history information; any discovery materials produced to Congress would redact email prefixes, telephone numbers, home addresses, conference call-in numbers, and Social Security numbers; 2 the names (and other law enforcement office information from which one might identify the names) of two Assistant United States Attorneys, three members of law enforcement, and one expert witness would not be redacted; and the names (and other information from which one might identify the names) of four witnesses would be redacted, unless they consent to the disclosure. The United States also informed estate counsel that the United States intended to agree to modify the Protective Order to permit disclosure to the public, subject to the same conditions applicable to the disclosure to Congress. The United States in fact does agree to such a modification. Estate counsel also agreed to provide counsel for JSTOR and The United States agreed to a more limited set of redactions for two AUSAs, but in the Motion the Estate appears to agree that this material should be redacted for those individuals as well. [See Motion at 4].

2

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 4 of 14

MIT a copy of any motion to modify the Protective Order so that JSTOR and MIT would have notice and an opportunity to intervene and be heard on the proposed modification. [Pirozzolo Decl. 3]. On one issue, the United States and estate counsel were unable to reach agreement, namely, whether the names (and other information from which one might identify the names) of other individuals appearing in the discovery materials should be disclosed without their consent. The United States informed estate counsel that whatever additional public benefit might exist by disclosing those names was, in this case, outweighed by the risk to those individuals of becoming targets of threats, harassment and abuse. [Pirozzolo Decl. 4]. The United States made clear that, if the individuals were notified and consented to the disclosure of their names, then no redaction would be necessary, but the United States would not agree to disclosure of their names without their consent. [Pirozzolo Decl. 4]. Estate counsel asserted that the disclosure of the names was necessary because one issue he and his client were focused on, along with Congress and the press, was the role and conduct of the institutional players. [Pirozzolo Decl. 4]. During the various conferences, the United States and estate counsel discussed other issues, which, while not matters of particular agreement or disagreement, are potentially material to the Courts consideration of the Motion. These issues include the following: Estate counsels client. On February 21, 2013, the United States asked estate counsel whom he represented in connection with the proposed modification of the protective order. Initially, estate counsel told the 4

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 5 of 14

United States that he represented the California-based law firm, Keker & Van Nest LLP (Keker), which had custody of the discovery material and had received the request from Congress. On March 1, 2013, estate counsel informed the United States that he also represented the Estate. Although the United States and estate counsel briefly discussed the question of who had standing to file a motion to modify the Protective Order, they did not discuss that issue in any meaningful detail. [Pirozzolo Decl. 5]. Discovery material discussing security methods and weaknesses. The Protective Order applies to certain discovery materials that disclosed security weaknesses and security methods in the JSTOR and MIT networks. Again, although the United States and estate counsel briefly discussed the issue, they did not resolve whether estate counsel would press for release of those materials in moving to modify the order. [Pirozzolo Decl. 6]. Review procedures for redactions prior to disclosure. Shortly before the Estate filed the Motion, the United States briefly discussed with estate counsel whether he had a position on the procedure to be used for allowing third parties -- JSTOR or MIT, for example -- to review the discovery materials should the Court modify the Protective Order to permit some discovery materials to be disclosed to Congress and the public. He said that he did not know yet what his position would be on the procedure to be followed. [Pirozzolo Decl. 7]. DISCUSSION A. Relevant Legal Framework The question of whether the Court should modify the Protective Order is governed, in the first instance, by Federal Criminal Rule 16(d)(1), which provides, in pertinent part: At any time, the court may, for good cause, deny, restrict or defer discovery or inspection, or grant other appropriate relief.

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 6 of 14

Fed. R. Crim. P. 16(d)(1). The Court has the discretion, pursuant to Rule 16(d)(1) and its inherent authority, to approve or modify a protective order. See United States v. Bulger, 283 F.R.D. 46, 53 (D. Mass. 2012). In assessing whether, and on what terms, to modify a protective order, the Court must weigh one partys need for modification against the other partys need for protection, and ought to factor in the availability of alternatives to better achieve both sides goals. Id. at 55 (quoting Murata Mfg. Co. Ltd. v. Bel Fuse, Inc., 234 F.R.D. 175, 180 (N.D. Ill. 2006)). In striking this balance, the rights of the victims must be given heavy weight. See Bulger, 283 F.R.D. at 55 (citing United States v. Salemme, 985 F. Supp. 193, 197 (D. Mass. 1997) (privacy interests of third parties may weigh heavily in deciding issues of impoundment)). In addition, because the Motion is requesting the disclosure of names (and other identifying information) appearing in discovery material, the Estate must establish a special need for that information, an especially difficult task. See United States v. Kravetz, 706 F.3d 47, 54-56 (1st Cir. 2013). Although the Estate correctly notes in its Motion the general rule that criminal proceedings are presumptively public, it incorrectly seems to assume that the general rule applies here. In Kravetz, the First Circuit said that no presumptive right to public access applies to criminal discovery materials. See id., 706 F.3d at 54-55 (We agree with those courts that have found that public access has little positive role in the criminal discovery process.). 3 Instead, disclosure of discovery materials should only be made upon a showing of special In Kravetz, the First Circuit held that no presumptive right of public access attaches to material obtained pursuant to Rule 17(c) subpoenas or related documents filed in connection with the underlying criminal prosecution. Id. at 56. The United States has been informed that MIT produced material to Keker pursuant to Rule 17(c). Estate counsel informed the United States that, in his view, the Protective Order does not apply to the 17(c) material. [Pirozzolo Decl. 8].

3

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 7 of 14

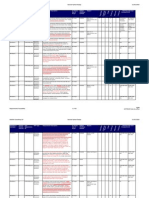

need. Id. at 56. Special need for these purposes means that the party seeking disclosure must make a compelling demonstration that disclosure of the [information] is required to meet the ends of justice. United States v. Charmer Industries, 711 F.2d 1164, 1175 (2d Cir. 1983); see also Kravetz, 706 F.3d at 56 (citing Charmer as describing relevant standard). Accordingly, in order to justify disclosing the names and identities the Estate must provide, as to each individual affected, a compelling demonstration that disclosure of the individuals name is required to meet the ends of justice. B. The Court Should Accept United States Proposed Redactions As noted earlier, the United States and the Estate disagree on whether the names (and other identifying information) should be redacted from the discovery materials before being made available to Congress and the public. In the United States view, personal identifying information should be redacted in order to protect the safety and security of the people named in the discovery materials. The Court should accept the United States proposed redactions because they strike the appropriate balance between the public interest in access to the information in the materials, on the one hand, and the public interest in protecting the safety and privacy of victims and witnesses, on the other. Furthermore, the Estate has not, and cannot, demonstrate the special need Kravetz requires to justify disclosure of the individual names at issue here. The United States agrees with the Estate that the substance of the discovery materials can and should be made available to Congress and the public. The redactions the United States has proposed, however, do not materially interfere with Congress or the publics access to the substance of the information disclosed. Attached at Tab A is an example of an e-mail supplied by MIT to the United States for purposes of this Response, with the proposed redactions. As is 7

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 8 of 14

evident from the example, the substance of the communication is not altered. In addition, because only the prefixes of the e-mail addresses are redacted, the institutions involved in the communication are identified. The only piece of information that is missing is the identity of certain speakers and recipients. That missing piece of information does not in any meaningful way interfere with what the Estate asserts is the central and stated goal of the Congressional inquiry: to understand how the investigation and prosecution proceeded, including how the evidence was gathered and then presented to this Court. [Motion at 7]. The precise identity of those communicating the information is at most tangentially relevant to that inquiry. In any event, whatever incremental public interest may exist in having the names and identities appear on the disclosed materials, it is far outweighed by the important interest in protecting people and organizations from retaliation, threats and harassment. Even before Mr. Swartzs suicide, organizations involved in this case faced threats from hackers operating under the banner Anonymous. [Pirozzolo Decl. 9, Tab A]. Following Mr. Swartzs suicide, the threats and harassment dramatically intensified. Hackers attacked the MIT campus computer network multiple times, attacking on January 13, 18 and 28. [Pirozzolo Decl. 10, Tab B]. On February 23, MIT received a hoax call that a gunman was on campus to retaliate against people involved in the suicide of Mr. Swartz and that the gunmans intended target was MIT President L. Raphael Reif, which led to a police response. [Pirozzolo Decl. 11, Tab C]. Hackers also claiming to be associated with Anonymous attacked the U.S. Sentencing Commission website and claimed to have obtained sensitive government documents that they would release. [Pirozzolo Decl. 12, Tab D].

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 9 of 14

In the weeks since Mr. Swartzs suicide, both United States Attorney Ortiz and her office have received harassing and, at times, threatening communications. [Pirozzolo Decl. 13]. U.S. Attorney Ortiz has also been targeted by protesters at her home. [Pirozzolo Decl. 14, Tab E]. In weighing the question of whether names should be redacted, the Court ought to take into account the personal cost such tactics might have on the private individuals whose names appear in the discovery materials, as well as the impact the arrival of masked individuals may have on their families and neighbors. It is worth remembering that the people whose names are at issue here did not voluntarily inject themselves into this matter. Rather, they were drawn in simply because they did their jobs. AUSA Heymann, the lead prosecutor on the case, has also been personally threatened and harassed. Shortly after Mr. Swartzs death became public, AUSA Heymanns personal information (including his home address, personal telephone number, and the names of family member and friends) were posted online. [Pirozzolo Decl. 15]. His Facebook page was hacked. [Pirozzolo Decl. 15]. He also received harassing and threatening communications, both orally and via e-mail. Here is one example: ROFLMAO just saw you were totally doxd over the weekend by Anonymous. How does it feel to become an enemy of the state? FYI, you might want to move out of the country and change your name . . . [Copying on the email personal information of AUSA Heymann]. [Pirozzolo Decl. 15]. AUSA Heymann also received a postcard at his home that has, on one side, U.S. Attorney Ortizs photo and, on the other side, a photo of a guillotine with a disembodied head that appears to be that of MITs President. [Pirozzolo Decl. 16, Tab F]. Also on the back side of the postcard, in the bottom corner, is a well-known symbol for Anonymous.

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 10 of 14

[Pirozzolo Decl. 16, Tab F]. Of far greater concern, however, is the fact that Mr. Heymanns father, Philip, a Professor at Harvard Law School who had absolutely nothing to do with this matter, received a similar postcard earlier this month. [Pirozzolo Decl. 17, Tab G]. This postcard is even more pointed in its message: the disembodied head pictured on the guillotine is Professor Heymanns. [Pirozzolo Decl. 17, Tab G]. The United States does not think it is appropriate to expose other people, particularly those who did not voluntarily inject themselves into this matter, to threats and harassment of this type under the circumstances here. The risk -- which is both specific and credible -- is simply too great to justify publishing the documents with the individuals names to Congress and the public. Indeed, the Estate has recognized and agreed that at least four individuals names should be redacted from the discovery materials, although it says that those individuals should be treated differently because they are private citizens who were not actively involved in either the Governments or any institutions investigation into Mr. Swartzs conduct. [Motion at 4-5]. Yet the other individuals whose names appear in the documents are no less private citizens because they work for either the government or an institution. They became involved in this case in response to events not of their creation and because it was part of their jobs. They should not, as a consequence, forfeit all privacy and face exposure to harassment and threats simply because they were doing their jobs. While it is true that some individuals names appearing in the discovery materials do appear in pleadings filed in this matter, that fact also should not change the balance the Court strikes here. When the earlier pleadings were filed, the threats and harassment directed at those associated with the prosecution of the case and their family members had not yet occurred to the 10

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 11 of 14

degree they are occurring now. Nor could this risk have been anticipated at the time and mitigated as it can be now. We know two simple things. First, there is now an unrestrained desire of unidentified individuals and groups to retaliate against people and organizations associated with the prosecution of Mr. Swartz and their family members. Second, the more peoples names and their involvement in the events leading up to the arrest of Mr. Swartz is publicized, the more likely they are to come to the attention of these vindictive individuals and groups and the more likely they are to be subject to harassment and threats. Furthermore, the AUSAs, the principal investigators of the matter, and an expert witness are willing to have their names remain in any discovery materials turned over to Congress and the public. To the extent there is additional scrutiny of their roles in this matter, the documents with their names on them are going to be the most pertinent. There is simply no need to expose other people involved in the case to potential harassment and abuse simply because they had some role in the underlying events or investigation. 4 The United States recognizes that the redaction of the identities and identifying information from the discovery materials will, at the margins, add a level of inconvenience for those who are reviewing the materials. That level of inconvenience should not tip the balance here, however. The risks of harassment and threat are too great. And the proposed redactions will, in general terms, permit readers to identify the source or destination of the communications such that they will be able to make intelligent assessments of the significance of the documents. The Estate also argues that JSTOR and MIT did not rely on the Protective Order when providing the information to the United States. That argument should be given little weight here. JSTOR and MIT largely produced information in response to law enforcement requests and subpoenas. They did not, as a result, forfeit their rights to the confidentiality and privacy of the information. See Kravetz, 706 F.3d at 54-56.

4

11

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 12 of 14

In short, the redactions proposed by the United States are reasonable. They strike an appropriate balance between the publics interest in the information, and the individual interests of people whose names appear in the documents. In any event, the Estates Motion shows no special need for the disclosure of those names, as required by Kravetz. It simply fails to make a compelling demonstration that disclosure of the [names] is required to meet the ends of justice. Charmer Industries, 711 F.2d at 1175. Accordingly, the Court should accept the redactions the United States has proposed. C. Other Issues 1. Standing. While the United States is willing to accommodate the request for disclosure of the discovery materials, the Motion does not appear to be the correct procedural mechanism to modify the Protective Order. It is by no means clear to the United States that the Estate is the correct legal entity to be filing the Motion. The case as to Mr. Swartz was dismissed in January 2013, and, so far as the United States can determine, the Protective Order did not create any rights or obligations of Mr. Swartz that would have passed to the Estate. The Estate does not explain in the Motion how it has standing. If the Court determines that the Estate does not have standing and denies the Motion on that basis, the United States nevertheless remains willing to assent to a modification of the Protective Order to proceed with disclosure of the information in accordance with and subject to the conditions it has proposed here. 2. Additional disclosure issues related to the discovery materials. Although the current focus of the Motion is on whether certain names should be redacted from the discovery materials, the Court may need to address other issues related to the proposed 12

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 13 of 14

modification. First, any modification should not include disclosure of discovery materials, such as those referenced in the Protective Order at 2(b), that discuss security weaknesses and security methods in the MIT and JSTOR networks. Second, there is additional information within the discovery that the United States and estate counsel did not discuss that, if disclosed, may compromise or threaten certain victims and witness privacy interest. This includes, among other things, personal history information, financial information and curriculum vitae information of potential witnesses. That information, which is in any event not relevant to the stated purpose of the requested modification, should also not be disclosed. Third, while the United States and estate counsel reached a general consensus on several issues, the precise parameters of certain categories of information to be withheld from production (e.g., the computer code, the criminal history information) were not defined in detail. The United States has no reason at this time to think that the parties disagree about the parameters, but would like to discuss those matters further with estate counsel so that, to the extent there may be disagreement, the parties can efficiently seek further guidance from the Court. 3. Notice to affected individuals and procedure for redactions. The United States requests that if the Court is inclined to modify the Protective Order, it also provide a procedure for notifying individuals potentially affected by the order so that (a) if the Court is inclined to have their names and identifying information disclosed, they are given an opportunity to be heard and object, under seal, and (b) if the Court is inclined to redact their names and identifying information, each individual will be given an opportunity to inform the parties that his or her name need not be redacted. The United States also requests that the Court

13

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111 Filed 03/29/13 Page 14 of 14

provide potentially affected entities and individuals an opportunity to review the redacted materials proposed to be made public before the materials are disclosed. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, the Court should modify the Protective Order in the manner specified by the United States and otherwise deny the relief sought by the Motion. Respectfully submitted, CARMEN M. ORTIZ United States Attorney By: /s/Jack W. Pirozzolo JACK W. PIROZZOLO First Assistant U.S. Attorney John Joseph Moakley United States Courthouse 1 Courthouse Way, Suite 9200 Boston, MA 02210 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Jack W. Pirozzolo, hereby certify that on March 29, 2013, I served a copy of the foregoing motion via electronic filing on counsel for the Estate. I have also separately served via email a copy of this Response on counsel for JSTOR and MIT. /s/ Jack W. Pirozzolo Jack W. Pirozzolo

14

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111-1 Filed 03/29/13 Page 1 of 2

Case 1:11-cr-10260-NMG Document 111-1 Filed 03/29/13 Page 2 of 2

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- House Judiciary Committee Discussion DraftDocument22 paginiHouse Judiciary Committee Discussion DraftJMartinezTheHillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- MIT Files Court Papers "Partially" Opposing Release of Aaron Swartz Investigation DocsDocument21 paginiMIT Files Court Papers "Partially" Opposing Release of Aaron Swartz Investigation DocsLeakSourceInfoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pirozzolo Response To Modifying Protective OrderDocument30 paginiPirozzolo Response To Modifying Protective OrderC FurmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- MIT Response To Modifying Protective OrderDocument3 paginiMIT Response To Modifying Protective OrderC FurmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Nsa/Css Storage Device Declassification ManualDocument7 paginiNsa/Css Storage Device Declassification ManualChetitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- What The Hell Is Jon Boutcher, Keith Surtees and Kenova Playing At? Martin McGartland Asks.Document3 paginiWhat The Hell Is Jon Boutcher, Keith Surtees and Kenova Playing At? Martin McGartland Asks.Marty MacÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Gaspard Responsive RecordsDocument371 paginiGaspard Responsive RecordsJake OffenhartzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Finding Aid - 911 Commission Records - National ArchivesDocument145 paginiFinding Aid - 911 Commission Records - National Archives9/11 Document Archive100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- House Armed Services Committee Report On Benghazi AttacksDocument31 paginiHouse Armed Services Committee Report On Benghazi AttacksThe Washington PostÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- US V Flynn: MOTION TO FILE PROPOSED REDACTED REPLY BRIEF AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOFDocument14 paginiUS V Flynn: MOTION TO FILE PROPOSED REDACTED REPLY BRIEF AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOFTechno Fog100% (5)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Due Diligence Report On Otto and Anthony LevandowskiDocument34 paginiDue Diligence Report On Otto and Anthony LevandowskiGawker.com100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- 14-01-29 Apple v. Samsung Order On Sanctions For DisclosuresDocument19 pagini14-01-29 Apple v. Samsung Order On Sanctions For DisclosuresFlorian Mueller100% (1)

- International Standard: Iso/Iec 27042Document24 paginiInternational Standard: Iso/Iec 27042Darni BtmuchsinÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- SO-034 Body Warn Camera GuidelinesDocument9 paginiSO-034 Body Warn Camera GuidelinesRyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Attachment To Miscellaneous Document - Pages 1 To 143Document143 paginiAttachment To Miscellaneous Document - Pages 1 To 14310News WTSPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Brava! DWG Viewer 7.1: User'S GuideDocument80 paginiBrava! DWG Viewer 7.1: User'S GuideConstantin MacsimÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- NPG Vs Tidal - Redacted Brief For Motion To CompelDocument27 paginiNPG Vs Tidal - Redacted Brief For Motion To CompelDigital Music News100% (1)

- Aug 22nd Order RE Trump MAL Search WarrantDocument13 paginiAug 22nd Order RE Trump MAL Search WarrantFile 411Încă nu există evaluări

- Pdfdocs 4.7 Product Comparisons: User InterfaceDocument3 paginiPdfdocs 4.7 Product Comparisons: User InterfacePaul WoollardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peter Debbins - Confession & More PDFDocument33 paginiPeter Debbins - Confession & More PDFVictor I NavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Worksheet in Deloittes System Design DocumentDocument32 paginiWorksheet in Deloittes System Design Documentascentcommerce100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- California UCC-1 StatementDocument5 paginiCalifornia UCC-1 StatementJered T. Ede100% (2)

- Perrion Winfrey Police ReportDocument12 paginiPerrion Winfrey Police ReportDan KadarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Waymo Calif DMV ComplaintDocument14 paginiWaymo Calif DMV Complaintahawkins8223Încă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Sanitization Secure Disposal StandardDocument6 paginiSanitization Secure Disposal StandardMagda FakhryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Authenticated Medical Documents Releasing With Privacy Protection and Release ControlDocument4 paginiAuthenticated Medical Documents Releasing With Privacy Protection and Release ControlInternational Journal of Trendy Research in Engineering and TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joule Letter About Columbia Utilities' FilingDocument9 paginiJoule Letter About Columbia Utilities' FilingDaily FreemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transcript of Sept. 12, 2014 Court ProceedingsDocument21 paginiTranscript of Sept. 12, 2014 Court ProceedingsgcappisÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Titus Presentation - 17.03Document96 paginiTitus Presentation - 17.03Andreea Avrigeanu100% (1)

- Loudoun County Public Schools Business and Financial Services Procurement Services 21000 Education Court, Suite 301 Ashburn, Virginia 20148 Telephone: 571-252-1270 Fax: 571-252-1432Document37 paginiLoudoun County Public Schools Business and Financial Services Procurement Services 21000 Education Court, Suite 301 Ashburn, Virginia 20148 Telephone: 571-252-1270 Fax: 571-252-1432RexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Documents Responsive To Executive Order 14040 Release Update Part 04Document105 paginiDocuments Responsive To Executive Order 14040 Release Update Part 04jimmyemandeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- CA Rules of Court 2018Document2.275 paginiCA Rules of Court 2018godardsfan100% (1)

- Clearswift - Product - Solution GuideDocument20 paginiClearswift - Product - Solution Guideshako12Încă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)