Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The French Lieutenant

Încărcat de

AdinanCDDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The French Lieutenant

Încărcat de

AdinanCDDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The French Lieutenant's Woman By John Fowles About The French Lieutenant's Woman

Next This novel is based on the nineteenth-century romantic or gothic novel, a literary genre which can trace its origins back to the eighteenth century. Although Fowles perfectly reproduces typical characters, situations, and even dialogue, the reader should always be aware of the irony inherent in Fowles' perception; for his perspective, however cleverly disguised, is that of the twentieth century. We see this both in the authorial intrusions, which comment on the mores of people in Victorian England, and in his choice of opening quotations, which are drawn from the writings of people whose observations belie the assumptions that most Victorians held about their world. Fowles is concerned in this novel with the effects of society on the individual's awareness of himself or herself and how that awareness dominates and distorts his or her entire life, including relationships with other people. All the main characters in this novel are molded by what they believe to be true about themselves and others. In this case, their lives are governed by what the Victorian Age thought was true about the nature of men and women and their relationships to each other. The French Lieutenant's Woman of the title, for example, is the dark, mysterious woman of the typical Victorian romantic novel. Sometimes the villainess, sometimes the heroine, such a woman was a symbol of what was forbidden. It is this aura of strangeness about Sarah Woodruff that first attracts Charles Smithson's attention. The story that develops around this pair echoes other romantic novels of a similar type, wherein a man falls in love with a strange and sometimes evil woman. Charles' relationship with Ernestina Freeman creates another sort of romantic story, one that formed the basis of many Victorian novels. In the present story, the romantic situation which develops around the pair of aristocratic young people is not allowed to prevail over the forces, including the dark lady, that would normally keep Charles and Ernestina apart. Thus Fowles uses the popularity of the comedy of manners and combines it with the drama and sensationalism of the gothic novel and, using several stylistic conventions, creates a masterful, many-layered mystery that is one of the finest pieces of modern literature.

The French Lieutenant's Woman By John Fowles Character List

Previous

Next

Sarah Woodruff She is an educated but impoverished young woman. She is called "the French Lieutenant's Woman" or "Tragedy" or the "French lieutenant's whore" because it is believed that she had an affair with a shipwrecked French sailor. It is also believed that she is half-mad with grief and that she stares out to sea, vainly hoping for the day he will return to her. Because of her reputation she can no longer gain any employment until Mrs. Poulteney hires her as a paid companion. Sarah is a mysterious figure. No one knows much about her, and later we find that much of what people believe about her is untrue. Charles Smithson He is a wealthy gentleman and is heir to a minor title. His hobby is collecting fossils and he considers himself to be something of a naturalist. He is an admirer of the controversial Darwin and he is rather pleased with himself that he is one of a minority in the 1860s to hold scientifically advanced ideas, such as the theories espoused by Darwin and others. He is both sensitive and intelligent, but he is unsure of himself. He is bored and dissatisfied with the course his life is taking. His fiance is Ernestina Freeman, but that relationship is changed when he meets Sarah Woodruff. Ernestina Freeman Ernestina is Charles' fiance. She is attractive and clever but also very young and naive. Although she considers herself to be a modern young woman, her attitudes are similar, for the most part, to those of most proper young ladies. She is vacationing in Lyme when the story opens, staying with Aunt Tranter. Aunt Tranter Ernestina's aunt is a kindly woman whose temperament contrasts greatly with that of the sharp-tongued Mrs. Poulteney. Aunt Tranter's honesty and lack of hypocrisy seem to present a welcome bright spot in the small town governed by the malicious gossip of less charitable souls. Mrs. Poulteney The vicar convinces the wealthy widow to take in Sarah Woodruff and give her employment. Mrs. Poulteney's main motive in doing so is to show how charitable she is, and it does not stem from any real feelings of compassion for Sarah. Mrs. Poulteney is a stereotype, a conglomerate of all the malicious old villainesses who have appeared in numerous Victorian novels. Dr. Grogan He is a friendly man whom Charles finds to be a sympathetic listener. Although he feels sorry for Sarah Woodruff, unlike Charles, he cannot take her seriously. He tries to convince Charles that she really is ill. Dr. Grogan, like Aunt Tranter, represents a type of Victorian character who seems more understanding and less hampered by convention than most people. Part of the reason for this is that both of the older people actually belong to the generation before Victoria's, an era somewhat less repressive in certain respects. Captain and Mrs. Talbot Sarah was the governess for the Talbot's children when she met the French lieutenant. Even after she told them of her experience with him, they did not condemn her for it.

Lieutenant Varguennes Caught in a shipwreck, his leg was injured, and Varguennes was nursed at the home of the Talbots, mostly by Sarah. Although he flirted with Sarah, and wished to seduce her, he was married, as she later found out. Mrs. Fairley She is Mrs. Poulteney's housekeeper and is as unkind as her mistress. She delights in spying on Sarah and reporting her activities to Mrs. Poulteney. Millie Mrs. Poulteney's young maid who is befriended by Sarah. Mary Aunt Tranter's maid whose life is considerably more pleasant than Millie's. She eventually marries Charles' man-servant, Sam Farrow. Sam Farrow While Sam is often the object of Charles' teasing, he is not merely a humorous figure as was Dickens' Sam Weller. He takes himself seriously and is an ambitious member of the working class. He is determined to wed Mary and make a good life for the two of them. Sir Robert Charles Smithson's uncle. It is his title that Charles hopes to inherit, although that prospect is altered when Sir Robert marries Mrs. Tomkins, an attractive widow. Lieutenant de la Roncire and Marie de Morell These are two individuals in a case history given to Charles by Dr. Grogan for him to read. The doctor hopes that reading about how the neurotic young woman convinced the French courts that she had been assaulted and her family sent poison-pen letters by the officer would convince Charles that Sarah possibly had similar intentions regarding him. While Charles conceded that the story might be true, he did not believe it applied to Sarah. Mr. Freeman He was a haberdasher who became very successful. One sign of his success was that he, a member of the middle class, could have his daughter marry one of the nobility. Gabriel and Christina Rosseti They were the founders of a school of art called the PreRaphaelite school. In their day they were considered as radical as Mr. Freeman was conservative. However, by the time Sarah came to stay with them, their work, while still shocking to some, was coming to be more accepted. John Fowles He is the bearded man who enters the novel several times as an observer and sometimes as a sort of theatrical director. He comments on the actions of his characters and discusses the relationship between the art of the novel and life.

Critical Essay Structure, Style, and Technique in The French Lieutenant's Woman

Previous

Next

In The French Lieutenant's Woman, John Fowles does not merely recreate a Victorian novel; neither does he parody one. He does a little of both, but also much more. The subject of this novel is essentially the same as that of his other works: the relationship between life and art, the artist and his creation, and the isolation resulting from an individual's struggle for selfhood. He works within the tradition of the Victorian novel and consciously uses its conventions to serve his own design, all the while carefully informing the reader exactly what he is doing. His style purposely combines a flowing nineteenth-century prose style with an anachronistic twentiethcentury perspective. Fowles is as concerned with the details of the setting as were his Victorian counterparts. But he is also conscious that he is setting a scene and does not hesitate to intrude into the narrative himself in order to show the reader how he manipulates reality through his art. Like Dickens, Fowles uses dialogue to reveal the personalities of his characters and often he will satirize them as well. For example, Charles' attitudes toward Sarah and Ernestina are revealed in the way he talks to them. He is forever uncomfortable with Sarah because she won't accept the way in which he categorizes the world, including his view of her. Sarah's responses to the world around her, as seen through her words and actions are consistent, for she is already aware of herself as an individual who cannot be defined by conventional roles. However, Charles changes, depending upon whom he talks to, because he really does not know who he is yet, and he sees himself as playing a series of roles. With his fiance, he is indulgent and paternal; with his servant Sam, he is patronizing and humorous at Sam's expense, and with Sarah, he is stiff and uncomfortable. When he attempts to respond to Sarah's honesty, he hears the hollowness of his own conventional responses. Fowles does not recreate his Victorian world uncritically. He focuses on those aspects of the Victorian era that would seem most alien to a modern reader. In particular, he is concerned with Victorian attitudes towards women, economics, science, and philosophy. In this romance, Fowles examines the problems of two socially and economically oppressed groups in nineteenth-century England: the poverty of the working and servant classes, and the economic and social entrapment of women. While the plot traces a love story, or what seems to be a love story, the reader questions what sort of love existed in a society where many marriages were based as much on economics as on love. This story is thus not really a romance at all, for Fowles' objective is not to unite his two protagonists, Sarah and Charles, but to show what each human being must face in life in order to be able to grow. While Fowles has titled his book The French Lieutenant's Woman, Sarah Woodruff is not really the central character. She does not change greatly in the novel as it progresses, for she has already arrived at an awareness that she must go beyond the definition of her individuality that society has imposed upon her. Because her situation was intolerable, she was forced to see through it and beyond it in order to find meaning and some sort of happiness in her life. In the early chapters of the novel, she perhaps makes one last effort to establish a life within the norms of Victorian society. She chooses the role of the outcast, the "French lieutenant's whore," and also falls in love with Charles or causes him to fall in love with her. But even as she draws

Charles away from his unquestioning acceptance of his life, she finds that she does not want to be rescued from her plight. She has already rescued herself. Charles, it seems, is the actual protagonist of this novel, for he must travel from ignorance to understanding, by following the woman whom he thinks he is helping, but who in fact is his mentor. He must discard each layer of the false Charles: Charles the naturalist, Charles the gentleman, Charles the rake, and perhaps even Charles the lover, in order to find Charles the human being. The knowledge he arrives at is bitter, for he has lost all his illusions, as Sarah discarded hers sometime before. But the result itself is not bitter. Although Charles and Sarah are not reunited, for life's answers are never as simple and perfect as those of art, they both achieve a maturity that enables them to control their lives as long as they remember to look for answers nowhere but in themselves. Fowles has taken two traditional romantic characters, a young hero and a mysterious woman, and has transformed them into human beings. There is no French lieutenant to pine after, and Sarah's life is not a tragedy that echoes her nickname in Lyme. Charles' gift of marriage is not a gift at all. While the novel could have ended with the couple's reconciliation, as it might have had it been a traditional romance, Fowles does not end it there. In the second ending, Sarah rejects the familiar security that Charles offers and both are forced to go on alone. Fowles' novel echoes the doubts raised by such novelists as Thomas Hardy, and by such poets as Matthew Arnold and Alfred Lord Tennyson, about the solidity of the Victorian view of the world. The world was changing and old standards no longer applied, though they lingered on long after many had discarded them in their hearts. This theme that was approached by writers in the nineteenth century is picked up again by Fowles and carried to a logical conclusion. The novel is therefore actually a psychological study of an individual rather than a romance. It is a novel of individual growth and the awareness of one's basic isolation which accompanies that growth.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The French Lieutenant's WomanDocument5 paginiThe French Lieutenant's WomanOanyta NituÎncă nu există evaluări

- Themes in French Lieutenant's WomanDocument5 paginiThemes in French Lieutenant's WomanSho50% (2)

- The French Lieutenant's WomanDocument11 paginiThe French Lieutenant's Womancrynutza5367% (3)

- Fowles The French Lieutenant's WomanDocument15 paginiFowles The French Lieutenant's WomanIoana Botar100% (2)

- The French LieutenantDocument4 paginiThe French LieutenantIoana OlteanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women in LoveDocument4 paginiWomen in LoveRavindra KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ernestina and Sarah in The View of Charles inDocument6 paginiErnestina and Sarah in The View of Charles inCristina PatuleaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The French Lieutenant's WomanDocument18 paginiThe French Lieutenant's WomanSonja Vjestica0% (1)

- EngLit in 20th CenturyDocument26 paginiEngLit in 20th CenturySpatar DianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essays Conrad Lord JimDocument2 paginiEssays Conrad Lord JimSzabo Florina100% (1)

- John FOWLSDocument7 paginiJohn FOWLSTah ReemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postmodern Narrative Technique in The FRDocument5 paginiPostmodern Narrative Technique in The FRAlina Maria CiofuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modernism, PM, Feminism & IntertextualityDocument8 paginiModernism, PM, Feminism & IntertextualityhashemfamilymemberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edward Said's Orientalism': A Post-Colonial Culture StudyDocument4 paginiEdward Said's Orientalism': A Post-Colonial Culture StudyIOSRjournal100% (2)

- The French Lieutenant's WomanDocument20 paginiThe French Lieutenant's WomanzzafrankhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Use of StreamDocument54 paginiThe Use of StreamVinícius BelvedereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Post Modern Feature in French Lieutenant's WomanDocument75 paginiPost Modern Feature in French Lieutenant's WomanMahin MondalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay: Heart of DarknessDocument5 paginiEssay: Heart of DarknessberndfranciscÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Painful CaseDocument11 paginiA Painful CasekashishÎncă nu există evaluări

- MWDS Huck FinnDocument6 paginiMWDS Huck FinnJosh RoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fall of The House of UsherDocument3 paginiThe Fall of The House of UsherLuana IvanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caesar and CleopatraDocument4 paginiCaesar and CleopatraPacurar EmmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Septimus Warren Smith As The Double of MDocument3 paginiSeptimus Warren Smith As The Double of MPriscila A. CustodioÎncă nu există evaluări

- The French Lieutenant's WomanDocument7 paginiThe French Lieutenant's WomanCristina Ioana NistorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cleanth Brooks Critical Essays - EnotesDocument7 paginiCleanth Brooks Critical Essays - EnotesAnonymous KKUs56YKÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 20th Century LiteratureDocument2 paginiThe 20th Century LiteraturePatricia BaldonedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jane AustenDocument2 paginiJane AustenMădălina RădulescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Symbolism of Colours - Moby DickDocument2 paginiSymbolism of Colours - Moby DickCristina-Raluca RuşeţÎncă nu există evaluări

- S.T. Coleridge's Treatment of The Supernatural in The Rime of The Ancient MarinerDocument8 paginiS.T. Coleridge's Treatment of The Supernatural in The Rime of The Ancient MarinerEunice kandlapalli100% (1)

- Precaution by Cooper, James Fenimore, 1789-1851Document239 paginiPrecaution by Cooper, James Fenimore, 1789-1851Gutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gappmaier - Thesis. Autobiography and MemoryDocument179 paginiGappmaier - Thesis. Autobiography and MemoryKaveen WeerasingheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tess of The D'urbervilles AnalysisDocument3 paginiTess of The D'urbervilles AnalysisTaniusha CebotariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moroccan EducationDocument26 paginiMoroccan EducationHassan MakhadÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Passage To IndiaDocument4 paginiA Passage To IndiaHarwindar Singh ButtarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Mark On The WallDocument2 paginiAnalysis of Mark On The Wallanon_227579204100% (3)

- Fowles vs. DickensDocument4 paginiFowles vs. Dickensboier_motocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Significance of LowoodDocument5 paginiSignificance of LowoodMichelle LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Changing PlacesDocument1 paginăChanging PlacesM2723Încă nu există evaluări

- Foe Vs Robinson CrusoeDocument3 paginiFoe Vs Robinson CrusoefroggybreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Novel 1: - English Studies - S5P1 - Number of The Module (M27) - Professor: Mohamed RakiiDocument9 paginiNovel 1: - English Studies - S5P1 - Number of The Module (M27) - Professor: Mohamed RakiiKai Kokoro100% (1)

- Examen Engleza LicentaDocument3 paginiExamen Engleza LicentaDobre Damaris67% (3)

- The History of Tom Jones1Document18 paginiThe History of Tom Jones1KATIE ANGELÎncă nu există evaluări

- Time in One Hundred Years of SolitudeDocument6 paginiTime in One Hundred Years of SolitudeMuhammad Umer Farooq BajwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Darkness Representing Evil in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (Another Critical Analysis)Document12 paginiThe Darkness Representing Evil in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (Another Critical Analysis)Shannon EvansÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Bildungsroman in Kazuo Ishiguro's Novel Never Let Me GoDocument10 paginiThe Bildungsroman in Kazuo Ishiguro's Novel Never Let Me Gopokretnizbun100% (1)

- Group 2 PronounDocument11 paginiGroup 2 PronounRichell TiongÎncă nu există evaluări

- The French Lieutenant's WomanDocument2 paginiThe French Lieutenant's WomanAlexu RdvÎncă nu există evaluări

- FAY WELDON, Down Among The Women: TasksDocument2 paginiFAY WELDON, Down Among The Women: TasksMihaela Miha TurleaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heart of Darkness, Novella by Joseph Conrad That WasDocument5 paginiHeart of Darkness, Novella by Joseph Conrad That WasAlbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Young Goodman BrownDocument4 paginiYoung Goodman BrownSzilvia Eva Kiss100% (1)

- 2020 ModernismCourseDocument5 pagini2020 ModernismCourseMikeÎncă nu există evaluări

- To The Lighthouse: Experiments in FictionDocument6 paginiTo The Lighthouse: Experiments in FictionAnthony ReadÎncă nu există evaluări

- EDIBLE WOMAN Novels For Students Vol 12 (Woolf)Document22 paginiEDIBLE WOMAN Novels For Students Vol 12 (Woolf)Ametist HagenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mark Twain and American Realism PaperDocument7 paginiMark Twain and American Realism Paperapi-235622086Încă nu există evaluări

- An Overview of Heart of DarknessDocument7 paginiAn Overview of Heart of DarknessNazar QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mrs DallowayDocument3 paginiMrs DallowayNathalie Messias de Andrade100% (2)

- The French LieutenantDocument5 paginiThe French LieutenantScarlat TeodoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brief Biography of John FowlesDocument14 paginiBrief Biography of John Fowlestoyland_malkia215479Încă nu există evaluări

- A Study Guide for John Fowles's "The French Lieutenant's Woman"De la EverandA Study Guide for John Fowles's "The French Lieutenant's Woman"Încă nu există evaluări

- The French LieutenantDocument3 paginiThe French LieutenantYasmin100% (1)

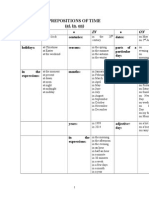

- Prepositions of Time (At, In, On)Document2 paginiPrepositions of Time (At, In, On)AdinanCDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjective or Adverb Worksheet With Grammar ExplanationDocument2 paginiAdjective or Adverb Worksheet With Grammar ExplanationFiffy ArmizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magic RealismDocument7 paginiMagic RealismAdinanCDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henry IvDocument1 paginăHenry IvAdinanCDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discuss in My Forum: National Organization For Women - NOWDocument6 paginiDiscuss in My Forum: National Organization For Women - NOWAdinanCDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edgar Allen Poe, The Tell-Tale HeartDocument6 paginiEdgar Allen Poe, The Tell-Tale HeartAdinanCDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Great Expectation by Charles DickensDocument2 paginiGreat Expectation by Charles Dickensوليد طهÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poetry Inquiry ProjectDocument13 paginiPoetry Inquiry Projectapi-321753124Încă nu există evaluări

- Feminist Literary Theory Learning Contract and Study PlanDocument4 paginiFeminist Literary Theory Learning Contract and Study PlanAriel ValdezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The BirthmarkDocument1 paginăThe Birthmarkapi-247477832Încă nu există evaluări

- 2 Red Red RoseDocument11 pagini2 Red Red RoseHuluu SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teachlive LessonDocument3 paginiTeachlive Lessonapi-294912070Încă nu există evaluări

- Akhtar Sheerani - Poems - : Classic Poetry SeriesDocument9 paginiAkhtar Sheerani - Poems - : Classic Poetry SeriesAzmat AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romantic Poetry PDFDocument21 paginiRomantic Poetry PDFBilly AmineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dark RomanticismDocument11 paginiDark RomanticismNazira OrtizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concept Notes On Literary History With Literary DimensionsDocument10 paginiConcept Notes On Literary History With Literary DimensionsLemuel Ian Batiller Cua50% (2)

- Grade 11 Short Story Unit PlanDocument18 paginiGrade 11 Short Story Unit Planapi-465927221100% (1)

- The DeadDocument16 paginiThe DeadUzhe ChávezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Free Download Here: Selection From Modern English Prose PDFDocument2 paginiFree Download Here: Selection From Modern English Prose PDFTouqeer Ahmad100% (1)

- Linear and Non-Linear Plot StructuresDocument14 paginiLinear and Non-Linear Plot StructuresHannah Flores0% (1)

- 4th Year Option Courses 2016-2017 PDFDocument103 pagini4th Year Option Courses 2016-2017 PDFAnonymous 6R9roykÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Chrysalids Character Diary ProjectDocument1 paginăThe Chrysalids Character Diary ProjectMich TheobaldsÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of British Literature HandoutDocument4 paginiHistory of British Literature HandoutSofia PonceÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSS Past 50 Years PapersDocument28 paginiCSS Past 50 Years PapersFaizan Siddiqui100% (3)

- Using Short Stories To Teach Language SkillsDocument20 paginiUsing Short Stories To Teach Language SkillsAririkakashikitoki Shikamo Shaarini RaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tom Jones As A Comic Epic in ProseDocument2 paginiTom Jones As A Comic Epic in ProseDipak Giri67% (3)

- Old Testament Presentation PDFDocument14 paginiOld Testament Presentation PDFThomas KvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discover Through Philippine Literature The Need To Work Cooperatively and Responsibly in Todays Global VillageDocument27 paginiDiscover Through Philippine Literature The Need To Work Cooperatively and Responsibly in Todays Global VillageDelgado Anthony100% (1)

- Eng 4Document5 paginiEng 4Sherl BenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Criticism I One Mark QuestionsDocument38 paginiLiterary Criticism I One Mark QuestionsmmdanwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Great Gatsby Essay PromptsDocument2 paginiThe Great Gatsby Essay PromptsKahloon ThamÎncă nu există evaluări

- To The LighthouseDocument38 paginiTo The Lighthousegensai kÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lenguaje Project A2-2 MARINADocument4 paginiLenguaje Project A2-2 MARINALiz Abarca100% (1)

- My Mother at Sixty Six PDF234Document5 paginiMy Mother at Sixty Six PDF234Prajith SprinťèřÎncă nu există evaluări

- R. K. Narayan's 'An Astrologer's Day'Document9 paginiR. K. Narayan's 'An Astrologer's Day'carolina6lina50% (2)

- Cave and Shadows (Summary and Reaction)Document2 paginiCave and Shadows (Summary and Reaction)Jhoana Jane Joson72% (18)