Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Formal Speech Acts As One Discourse

Încărcat de

Pedro Alberto SanchezTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Formal Speech Acts As One Discourse

Încărcat de

Pedro Alberto SanchezDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Formal Speech Acts as One Discourse Author(s): Signe Howell Reviewed work(s): Source: Man, New Series, Vol.

21, No. 1 (Mar., 1986), pp. 79-101 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2802648 . Accessed: 16/01/2013 14:11

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Man.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FORMAL

SPEECH

ACTS AS ONE DISCOURSE

SIGNE HOWELL

University ofEdinburgh

Unlike the situationin America where the proponentsof ethnography of speaking (or the studyof the roles of formalised performative folklore)have revitalised speech in society, in thisarea. This article have shownlittle interest British anthropologists attempts to developthe of speaking.Based on datacollected ideas generated by theethnographers among theChewong, an aboriginalgroup in the Malay Peninsula,a methodis proposed forexaminingall manifestations offormal each genrein itsrelation speechactsof a societyas a totaldiscourse; studying to theothers. to a setofcriteria-concernThus, myths, songsand spellsareall examined according ing origins,form,content, performance etc. It is foundthatwhile mythsand songs emergeas whollycontrasted, thespellsoccupya synthesising positionwithregard to mostcharacteristics. wherein'effective' This conclusionis linked to indigenousepistemology knowledgeis most and songsareconstitutive oftraditional highly valued. Whilemyths knowledge,songsand spells in achievingaction. Unlike songs, however,spellsdo so in themselves-they are instrumental own right. words as actorsin their represent

WithinBritishsocial anthropologytherehas been notablylittleinterest in formalspeech acts1as a fieldof study. This neglecthas been attributed by Finnegan to two main factors:the theoryof unilinearevolution, and the functionalism ofMalinowski(FinneganI969). Because Tylor,Frazerand Lang oftheFolk-loreSociety,thestudyofmyth wereactivemembers the was, from very beginning,closely associatedwith the nineteenth-century evolutionary thetheoretical of man; and withthedemiseof thattheory, foundations theory for the study of mythalso collapsed. Subsequentanthropological attitudes viewsofMalinowskiandhis wereinfluenced towardsmythology bythenarrow to maintain theexisting socialand political conceptof'mythas charter', serving in Malinowski strand order(MalinowskiI948a). Therewas, however,another into the Britishtradition, which was not so readilyincorporated namelyhis on regarding thanas a countersign insistence languageas a mode ofactionrather

of thought (1948b: 243-5I;

stimulusand theresponseof the audiencemeansas much to thenativeas the text'(1948a: 82). It was, however,notuntilmuchlater-and in America-that theseideas were to be takenup and developed(see e.g. Ben-Amos& Goldstein in the 1975: 2). Over the past two decades we can observe a renaissance have shown as little Americanstudyof 'folk-lore'.On thewhole, theBritish as in Malinowski'sideas on language. in thisnew development interest

Man(N.S.) 21,

79-101

lifeless . . . The whole nature of the performance, the voice, the mimicry, the

of language. Thus he states,'The of the 'contextof thesituation' significance but withoutthe contextit remains text, of course, is extremely important,

1935:

II); and his stress upon the theoretical

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8o

SIGNE HOWELL

in Britainwas Thus, the main genreof formalspeech to receiveattention myths, and theseweretreated notfortheir own intrinsic interest, butto further in the one case to validatea theoretical concernsof the writers: the particular of man;in theotherto validatea particular particular theory ofsociety. theory Levi-Strauss'ssuggestionthatmythscan tellus about theproperties of the humanmindis, in thefinal analysis, yetanother exampleofa theoretician using hisown particular myths to substantiate argument. However,thepublication of his earlyessays on the structural studyof mythtogether with the foursubin mythology in Britain,and thestructural revivalof interest analysisof texts was attempted ofthemethodareLeach and by several.Two notableexponents in thenineteen-sixties, Willis.The former, his controversial havingpublished, structural from theOld Testament analysesofincidents (Leach I969), returned to the same themein I983 (Leach & Aycock I983). Willispublishedseveral structural analysesofFipa 'spokenart'(I967; I98I) and, mostrecently, brought world the work of the Belgian to the attentionof the English-speaking and committed Africanist Luc de Heusch, through his annoLevi-Straussian, of the latter'sanalysisof CentralBantu myths(de Heusch tated translation in the structural I982). But, despitetheirinitialinterest studyof myth,the convincedby Levi-Strauss's British were neverfully arguments (see e. g. Leach continuedto be ignored. Certainly,the oral implications traditions, of the are littleconsidered natureof 'oral literature' (see Finnegan1977) although the of African Literature has somewhatrectified appearanceof theOxfordLibrary In a related,but somewhatdifferent thesituation. the vein,one mustmention and non-literacy done by Goody (e.g. Goody 1977). While work on literacy has undertaken severaldetailedstudiesof thedifferent Finnegan genresof 'oral

1970; 1977) I967;

ofMythologiques sequent volumes (I963;

1970;

1973;

1978; I98I)

in a resulted

Kirk1970), and,byandlarge, with myths, together other forms oforal

she treats the Malinowskian'contextof situation', each manifestation of 'oral literature'-legend,poetry,drama, riddleand proverb-as a separateenteris to suggesta different prise.The purposeof thisarticle approach,namelyto all thegenres offormal treat as one discourse. speechactswithin anyone society The situationin America evolved ratherdifferently fromthatin Britain. in the studyof what There one may witnessa long and continuoustradition became tendsto be called folklore.Over theyears,mainstream anthropology concerns divorced from folklorestudies, and until recently the theoretical thisseparation.The text,in isolationfromits social setting, reflected was the or by formalanalysis object of study;eitherthroughthematic classification, influenced morebyPropp (1958) thanbyLevi-Strauss. Withthepublication ofa

in Africa literature' (Finnegan I967;

andconsiders to someextent

and anthropologists betweenfolklorists ofinterests in thenew merging resulted of speaking'or 'performative folk-lore'. Here we can observea 'ethnography shift thestudyoftextto thestudyofthecontext from oftheperformance ofthe such as context, folklore (see also Dundes I964). New key terms performance and communication ofthedynamics emergein whatis becominga study ofthe betweenaudienceand performer. 'The taskof theethnographer encounter of and analyzethe dynamicinterrelationships speakingis to identify among the

series of articles by Dell Hymes(I962;

I964;

I967

a fruitful etc.),however,

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

8i

towardsthe construction of a elementswhich go to make up performance, descriptive theoryof speaking as a culturalsystemin a particular society' (Bauman & Sherzer1974: 7). In thewords ofAbrahams(I975: 288), one ofthe of the approach, 'the folklorist has been early advocates and practitioners concernedwith the stylistics of his material, and it is out of this traditionally backgroundthat we have generatedour own perspectives.Exploring the therelationship of structure of theitemsof performance, and, more recently, the performance-centred these items to the operationof theirperformance, folklorist has beenascertaining theplaceofcreative and stylistic communication in thespecific group'. In other words,we notea shift to thesocialsetting ofverbalcommunication, and to itsplacein thewiderideologyofthegroup.Withthischangein focus,an in the definition accompanyinginterest of what can legitimately be said to has also emerged,and to the traditional constitute folklore genresof myths, legends,folk-tales and theballad,have beenaddedriddles, proverbs, greetings, andsongs ditties etal. 1970). (seee.g. Abrahams 1972; Ben-Amos 1972; Dundes whichhave resulted Common to all thepublications from the'ethnography of speaking' is a firmethnographic base. Each is an in-depthstudy of, most commonly, one genre of formalspeech act withinthe social settingof its performance. It seems to me thatthestudiesfallbroadlyintotwo mainkinds. First,thosewhich attempt to discoverthe 'groundrules' forspeechactivities within anyone culture (see Bauman& Sherzer 1974: 89). Thisinvolves a detailed of theperformance. of the actual setting description Hence, much more than the language used on such occasions has to be studied.Certainly, the actual narratives of theraconteur mustbe transcribed, but so musttheinterruptions theaudienceand theresponses In suchstudies from by theperformer. there is a strong emphasis upon thesituational frame. Context,ambianceandtheprevailconditionsare noted,and oftentheanalyst ing external triesto recordseveral in different of thesame textand seeksto accountfordifferences performances and the relationship betweenthosepresent(e.g. Abrahams the performance I982; Basgoz 1975; Hymes 1975; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1975). Secondly, thereare studies which examine the manipulative possibilities whether thisbe a storytellingevent(e.g. Basgoz available to theperformer, jokes or riddlesbetweenmembersof a peer group (e.g. Bauman & McCabe

1970;

conventions 1975), greeting (e.g. Irvine 1974;

Salmond of 1974), orthe interplay

and concepts terms to conductsuchanalysis. clarify appropriate Yet another preoccupation maybe detected, which,I would argue,has been lessdevelopedthantheother two. This concerns theincorporation ofthespeech eventintotheothercultural of thesociety, or group,in question,so categories of theperformance, that,not only mustone takeaccountof thesocial context one must also place the speech act withinthe ideological framework of the have recognised group. Some writers thetheoretical significance ofcosmology made an integral (see e.g. Toelken 1975; Abrahams1975) butitis rarely partof in non-literate theanalysis.It is one of themajorcontentions ofthisarticle that, a cosmologicaloverviewis ofcrucial societies, importance. As thesophistication of theinterpretation and presentation of actualspeech

Ben-Amos1976; Dundes 1970). Throughout, thewriters attempt to

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82

SIGNE HOWELL

events is improving, mostofthewriters focustheir studies on selected of genres folklore withina particular society.Most commonlyone genreis examinedin in thesociety. greatdetail,withlittle or no reference to other genres also present in orderto illustrate a Occasionally two, or more, genresmay be contrasted particular point.Thus, Fox, in his studyof Rotineseritual language,examines is to demonstrate different categoriesof such language,but his main interest formal their identity, beingall based on dyadicsets(Fox 1974). To my knowledge, Willis is alone in attempting to provide an ordered of a society'sformalspeech acts. Taking the four expositionof the totality genresof Fipa 'spoken art' he sets up a matrixof the total semanticfield, matrixcreatedby Douglas (I973), in whichhe reminiscent of the grid-group considers 'two modal parameters-formal-linguistic and social-structural' Willisunfortunately does not (Willis1978: 8). Whilehisis an original approach, demonstrate develop themodel in anydetail,and hencedoes not convincingly is no attempt atplacingtheFipa formal itsvalidity. Moreover,there speechacts in a dynamicrelationship. The main part of the book consistsof numerous withbrief remarks verbatim examplesof thefourgenres together introductory characteristics ofthesocialcontext oftheperformance of thegeneral concerning each. and folklorists have clearly advancedour underWhiletheseanthropologists of language, and more particularly of the standingof the social significance there remain several issuesin connexion variousgenresof 'folklore', important with the studyof formalspeech acts. I suggestthatinsteadof treating each in anyone culture, offormal category speechactsas a separate enterprise making connexionsas may be appropriate, all whateversocial, symbolicor structural a society shouldbe looked at together as one offormal genres speechactswithin Itwas whilepreparing for theseventy-odd discourse. whichI publication myths had collectedduringmy fieldwork withtheChewong of theMalay Peninsula theplace ofmyth in Chewong (Howell I982), thatI realisedthatto understand it was insufsocietyand cosmology, and theirepistemological significance, ficient to look at themin isolation.They constitute one partofa larger discourse whichincludesall Chewong genres offormal case myths, speechacts-in their all three as a totality, themeaning ofeachemerges songsand spells.By treating in relationto the rest,and the overallsignificance of thediscoursewithinthe becomesapparent. ideologyitself The Chewong The Chewong area smallgroupofaboriginal peopleofthetropical rainforest of the Malay Peninsula. They total some 260 individuals,and today they are dividedintotwo mainparts.Whereasone parthas been drawnto some extent into the wider Malaysiansociety,the otherlives deep insidetheforest where and shifting they practise hunting, gathering cultivation, and their contact with theoutsideworldis minimal-confinedto theoccasionalsale ofjungleproduce in orderto buy knives,salt,clothand tobacco. It was amongthislatter section and it is about (theEasternChewong) thatI conductedmostof my fieldwork themI shallbe speaking.The EasternChewonglivein smallsettlements widely

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

83

an area of about I90 square miles which theyregardas scattered throughout The settlements their traditional arechangedeveryone to three territory. years, new ones beingclearedby theslashand burnmethod.They have no domestic animalsand relyon theforest to supplythemwithmeatand otherfoods.They frequently fields abandontheir fordays,or even weeks,in orderto go hunting and foraging.The compositionof any one settlement undergoescontinual eachconsists oftwo or three housesoccupiedbyan change,butmostfrequently withtheir married children elderly couple and one or two of their families. is extremely with no Kinshipis cognatic,and social organisation informal fixedgroupsor politicalhierarchies. Thereis no machinery oflaw and punishin humansociety.Rather, a largenumber mentfounded of different categories of superhuman and non-humanbeings are drawn into the conduct of daily affairs via the medium of a set of rules which informand directhuman in non-human in the of whichresults retribution behaviour,thetransgression form ofillnessofall kindsor 'natural The Chewong recognise no catastrophes'. explanationfor such events outside the superhumandomain, and I have suggestedelsewhere(Howell I984) that,at one level of discussion,Chewong not onlyof the260 individuals, butalso as consisting societymustbe regarded ofthenumerous their universe. Consideration superhuman beingswho inhabit of thesebeingsinfluences almost everyindividualand collectiveaction. This is maintained andrecreated widersocialuniverse ofexchange through processes whichoccurdailyas well as undermoreformal circumstances. The myths, the songs and the spells all feature,with varyingemphasis, both human and superhumanbeings. In view of this it is not meaningfulto distinguish a sacred-profane between 'ritual' and dichotomy. An analyst's distinction cannotbe identified; 'mundane' concernsand activities theseare intertwined I wishto and on that ofaction.Arising from -both on thelevelofthought this, to makean analytic distinction betweenmyths thatitis unhelpful arguefurther and legends as is commonlydone (see Kirk 1970 for a discussionof issues All Chewong 'tales fromlong ago' are formally involved in definitions). similar.All displaysome humanand superhuman elements; everyactionand I shalltherefore is invariably character exhibiting cosmologicalconsiderations. to all Chewong tales. use thetermmyth to refer Theinterpretation Myths,songs and spellsconstitute thetotality of Chewong formal speechacts. Othercommonlyfoundgenres suchas drama,poetry, ballads,speechmaking, proverbs, riddlesor greetings are not present. Moreover,theyarenot particuin languageor languagemanipulation larlyinterested as such. Skilful language use in an individual is nothighly valuedas itis in manyothercultures (see Peek and punningor otherreflexive I98i) language uses are virtually unknown. People do single out their myths, songs and spells, however, as having something in common which distinguishes them from ordinaryspeech. Interestingly, the threeformalspeech acts are thoughtof as similaras much becauseoftheir as becauseoftheir content form. Thereis no overallterm forthe three.Nor, as faras I can tell,are thereanylinguistic linksbetweentheterms

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84

SIGNE HOWELL

duidui (telling stories fromlong ago2) is theexpression for used foreach; kitra boththeactofsinging as well as thesongitself; and 'myth';ninghaegen expresses or charm)meansan incantation, or tankal (from theMalay3meaninga talisman is linguistically 'spell' and is also a verbalform.None of theseterms related to klugn (languageas well as theactofspeaking)or badd (to say). During my early investigations into these three genres, one was often that'songs arejust like explainedin termsof another.I was told,forinstance, spells'or, 'spellsarelikesongs',or 'spellsarelikestories', or moreemphatically, 'songs are spells'. The questionthenariseson what basis the Chewong make suchstatements. An examination of the myths, songs and spellsrevealsthatthesedo in fact and thissomething have much in common. They are all saying something, is linkedto whattheChewong calltheir 'traditional alwaysintimately knowledge' asal, strictly 'knowledge/knowing original' from the Arabic, via (haeraten What mean Malay, asal, origin,history). they by thisis knowledgeabout the for aretheway they are Chewong universe, providing explanations whythings and how events occur out of for and why specific and,arising this, prescriptions action. In any society,knowledge is the resultof social processes;a social a diachronic as well as a synchronic whichmustbe looked at from achievement as as the of it. well from ideas concerning perspective, perspective indigenous Knowledge changesover time dependingon individuals, events,outsideinanditis one manifestation andmanyother factors ofa society's fluences identity. One of the ways thata society'sbody of knowledgeis transmitted, recreated Othermediaare,ofcourse,the and changedis via thatsociety'soraltraditions. and variousritual thekinsystem socialinstitutions, practices. Traditionalknowledgeis transmitted, however,in ordinary speechacts as to explain the well. The choice of subject matteris therefore not sufficient linkmade betweenthethree offormal conceptual Chewong genres speechacts. What distinguishes theknowledgeof Chewong myths, songs and spellsfrom is the fact that each of the three the knowledge of ordinaryconversation manner.Thus, althoughlanguage is expressesthe contentin a formalised to employedin all cases, in formalised speech, the language used conforms certain restrictive to Political expressive conventions. In his introduction intraditional andoratory Bloch4proposesa definition of 'an ideal language society, thisto 'an ideal typeof ordinary typeof formalised speechact' by contrasting speechact' (Bloch 1975: 12). Formalised speechactsarecharacterised by: 'fixed limited choiceofintonation, some syntactic languagepatterns, extremely forms of sequencing,illustrations fromcertain excluded, partialvocabulary,fixity limitedsources,e. g. scriptures, rulesconsciously proverbs, stylistic appliedat all levels' (1975: 13). His main concernis to demonstrate thatformalisation of ofpowerand coercion-an aspectwithwhichI languagemaybe used as a form am not concerned here,but one whichis dealtwithby manyof theethnograin varying phersof speaking.Chewong myths, songs and spellsall conform, of formalised degrees, to Bloch's definition speech acts. I would add one which in my view is integral to any such definition, criterion namelythatof performance. My third pointin establishing whytheChewong makea concepofformal mustall tuallinkbetweentheir three that genres speechis thisfact they

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

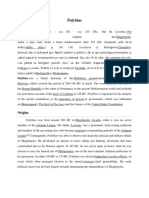

be performed. They are all clearly markedofffrom ordinary verbalcommunicationsby thecreation ofa particular inwhichone or morepersons setting gives a performance in front of therest.Furthermore, suchperformances are put on forsome special effect. I therefore agree withHymes, when he states,'Most important forthepresent purposeis theshowingthatperformance, as cultural behaviourforwhicha personassumesresponsibility to an audience,is a quite specific, quite specialcategory.Performance is not a wastebasket, but a keyto much of the difference in meaningof life as betweencommunities . . . the existspartly tradition forthesakeofperformance; performance is itself an partly A performance of Chewong formal speechactsis setapartin bothspace and timefrom thatofordinary speechacts.Bloch saysthat,'Formalisation removes theauthority and theeventfromthespeakerhimself, so thathe speakswhen less and less forhimself using formalisation and more and more forhis role' (1975: i6), and I would suggest that this may be broughtto bear on the performative aspect.A rolemustnecessarily be performed. Itis thusnotjustthe form and thecontent offormalised speechactswhicharerestricted, butalso the time and the place of theirperformance. Their utterance is therefore closely linked to specificsocial contexts.It is this aspect that the ethnography of speakinghas brought out so convincingly. I shallbeginby setting out thecharacteristics according to whicheachformal speech categoryis to be judged. The criteria are derivedlargelyfromthe Chewong themselves, but I have added some of my own, particularly those to theformal pertaining aspects.I then ofspeechact-myths comparetwo types and songs. Next I assess thespells,so thata detailedmatrix of information is established which allows each category of speechto be locatedin termsof the totaldiscourse.This revealsthatthespellsgenerally occupya medianposition, i.e. they oftheopposedcharacteristics displaya mixture inbothsongsand found legends.Occasionally,theysharetheidentical attribute ofonlyone (see fig.for an expositionof the characteristics of each genre).Finally,I discussthe value attached by theChewong to eachofthethree The purposeofmyths genres. is to perpetuate knowledge; the purpose of songs is to allow the additionof new knowledge and also to apply thatknowledgeto maintain relations with the worldsand to restore superhuman order;spellsuse knowledgeto achievesome specific objective.This, I suggest,is consistent withthehigher value attached to thespellsas comparedto theothergenres offormalised speech. I have investigated thefollowingcharacteristics (see fig. i): How does each genrecome intoexistence or do theyconstitute (aretheycreated by individuals receivedknowledgefromthe past)?Who owns theverbalproducts(are they exclusive or communal)? Who mayperform them? Whatsubjects and characters are considered suitablefordifferent Whatis thetemporal What genres? setting? is theimportance in any of thenarrative be altered sequence?May thecontent way? Closely linked to contentis the question of form. Here I consider and sequencing.Then vocabulary,metre,syntax,rhythm, comprehensibility followquestions is this to do withperformance: linked to specific occasions? Are there restrictions as to timeand place?Whatis theroleoftheaudience? Whatis and whatritual theactualmode employedby theperformer, observations must

end' (1975:

I8/g9).

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

86

SIGNE HOWELL

I=: :5 r. u U r. M OU

o o-l:$u

0

4

0 o C).

u

X u u

-0

0-0

(I

-,: a r,-"

0 u

u

u

u 0 > m0 >

:5

:; Z 0 0

u u u o u Z o Z 'V-)

v4-),

Fo

bD

:5 -1:

-a W

:5

Wu -0 O.u 4., >

x 0u

-,:s

-a

Q-r-

uo

0

4.,

4.,

-':$

94

-18 r-L4

4.1

v, <ur-WL4

u

z >

V)

O.-

U r-L4

bD

0 u u O O 94U v. (.X

u u

u 4 0 X u t+0 .4

>

4., W

CL4

u

u

0 >1 u -u U

0

u >

>, I:L,

1.4 -

C). r.

r-L4 0 u x u (n0 .u u

cl

cl

u -0 cl u

u

u U-C.u M0 U W

CL4 V) 0 >

u

W u

u

>1 1.4 1.0 >"W 1.4 4.,

i

>1 >

1.4

Z r.

4., cl

-0 0

W.4 0

z

4., r.

'OOZ V) r-'L4

0 W 1.4

-0

-er.

Cl

4-

u u u

u 0

V. a4

0

0

bD 0

O

tn 1.0 u

u U U 4.,

bD

cl

bD bD

u r .

13 g

(D

c) 0

V') V-)

u V)

9L4

C2t r-L4

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

87

be adheredto? What is the purpose of the performance? (see Appendix for examplesof a Chewong myth, song, and spell). andsongs Myths a. Originsand durability. According to the Chewong, the mythscame into in thedistant existence past.Theyhave existed, unchanged, throughout timeto be toldintothefuture. They arepassedfrom generation to generation and their authors are unknown,their veryanonymity contributing to their authenticity. They arestories abouteventsthat arethought to haveoccurred, and arenothing more than the recordof those who witnessedthem. The Chewong refer to as 'telling myths fromlong ago' and insist thattheseareone of thechief means by whichtheygaintheir collective 'original knowledge'.'Ifwe do notremember thestoriesfromlong ago, we do not know how do things is a properly', common statement, and I was oftentold how important it is to telleach tale so thattheylearnthem,and learnfromthem.The to the children repeatedly theancestors. area commonheritage from myths Songs, by contrast, areregarded as individual creations, theorigins ofwhich arenevertheless superhuman. A songis givento an individual by a superhuman being in an encounter. The encounter may takeplace in a dream,in a trance induced duringa singingseance, or in a waking meetingin thejungle. Any object or being may reveal itselfas a conscious being (i.e. endowed with consciousness, ruwai),and whenit does so it becomesthatperson'sspirit guide (ruwai). The relationship, which is describedas one of husband-wife or of is cemented parent-child, by thegift ofa song,and thepersonwho has received it acknowledgestherelationship by singingit on future ceremonial occasions. Subsequentadditionsmay be made to a song by its owners.New descriptions and eventsexperienced of beings encountered may be inserted duringtrance stateswhenthe'soul' ofthesinger(ruwai)travels. b. Ownership. Mythsbelongto everyChewong,old and young.They area gift fromthe ancestors,and represent a major part of Chewong group identity. Being withoutsuchsocial categories as guardians ofknowledgeor overseers of behaviour,everyoneis drawn directly into the process of ensuringthe continuation of society.Such knowledgeis notexclusive, itis necessary rather that everyChewong knows thecorrect way to behave,theunderlying reasonsfor prescriptions and the expectedresultsof transgression. The mythsconstitute one stablemeans of ensuring correct behaviourand musttherefore be everyone's property: knownby all, toldby all. The songs, by contrast, are individualproperty. Once a new song has been madepublicin a singing seanceitis thenceforth referred to as 'thesong ofX'. A song may also be passed fromone personto another, usuallytogether withthe associatedspirit guide. Such songs may be sungby therecipient onlyafter the deathoftheoriginal owner.I am uncertain, however,aboutthetransmission of is that,ideally,it shouldneveroccur;thatsongslive onlyas songs. My feeling long as theiroriginators.More importantly, it is maintained that only the

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

88

SIGNE HOWELL

owners can understand the meaningof theirsongs (thiswill be returned to below). Songs are intensely personal:theyare not only privateproperty, but theyalso represent private knowledge. c. Content. Mythsarestories aboutpeople withwhom theChewong can easily identify, and about ordinary events-but people and eventsof thedistant past. Some lay down first how individualand social existence principles explaining first came about. Otherscan be seen as case studiesof thevariousruleswhich in a society to theconduct ofsociallife withno governbehaviour-so important institutionalised chains of authority. Such mythsdescribetransgressions of variousrules,and their repercussions. Othersdescribe feats ofpeoplepossessing withthesuperhuman esoteric knowledge(putao)5and their relationship beings. All the mythsare centredon humanexistenceand the main characters are always human beings. They also confirmthe involvementof superhuman the epistemologicalconjunction beings in ordinarylife, therebyaffirming betweenthesocialand thecosmological.In dailylife, theChewongrefer to their myths whenthey needto provideevidence fora particular statement. Mythsare demandsoftheir also used tojustify parents' children. Whenevermyths are told, it is of the utmost importancethat they be reproducedcorrectly. The incidents mustbe relatedin their propersequence, and all theappropriate detailsmustbe included.No additionsor subtractions maybe made. WhenI visited theWestern on tapesome of Chewong,I recorded theirmyths.The EasternChewong on my return were verydismayedto hear the tapes. Whereas most of the events related were known to them, the in thewesthad, as it were,reshuffled raconteurs themintodifferent sequences. initial After their theEastern surprise, Chewong becameveryscornful, 'theydo notknow thetraditional stories correctly', they in toldme,andsoon lostinterest listening to them. The songs are not primarily about humans and theirpreoccupations, but is describe theactionsand habitats of thesuperhuman beings.The information in front as one narrative each not presented unfolding of theaudience.Rather, in terms of songis madeup ofseveralself-contained sequencesoften incomplete the information or story given, and variouslydescribingthe superhuman theencounters as s/heexperiences them.The songs worldsand/or ofthesinger and unconnected into are thusa medleyof manydifferent parts,each merging thenext-all somehow intertwining witheach other.Whilederivedfromthe in ways which of songsis presented body of common knowledge,thecontent are incomprehensible to the outsider-and to manyChewong as well. Songs contain invocations to spirit guides and dead ancestors,all of whom are in their to attend theseanceand helpthesingers requested particular quest.The mainpurposeof thesepassagesis to attract their attention and enlisttheir help. out on a potentially The singers send their 'soul' (ruwai) and dangerousjourney are dependentupon superhumanco-operation.Sometimesthe spiritguides their other themselves thesongdescribing speakthrough way oflife;sometimes the describe the sometimes superhuman beings interrupt; singers beings and Much of the is or their ruwai encounter. content places implicit obliquely

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

89

referred to throughallusions. In all theserespectsthe songs differ markedly fromthemyths in whicha plot is developedin a way thattheWestern listener can easilyfollow-once theculturally specific conceptsareunderstood. At the explicit level, each myth contains only one plot, and this is introduced, developedand concludedin a straightforward, logicalmanner. In thecase ofa healingseance,thesinger maydescribe how s/he goes insearch of thelost ruwai of thepatient, and ifs/hefinds it,s/hedescribes thebeingwho has abductedit and whatis demandedin exchangeforthereturn of theruwai. Throughout, the spiritguides warn of impendingdangers threatening the ruwai of thesingeras well as thepeople back at home keepingup the travelling drummingand chorus. The parts of a song are jumbled up together, but whenever has beensung,thenitis vitalthat, in future something performances, all previous utterances are repeatedverbatim.At each performance every existing partof a song mustbe faithfully rendered, buttheactualsequencing of theseis unimportant. New partsmaybe inserted betweenexisting parts. Each new song, or new partofa song,introduces new information aboutthe worlds. New chainsof causality This knowlsuperhuman maybe established. intopublicknowledge.As such,thesongsconstitute edge is thenincorporated thechief mediumforchangein Chewongideasas thefollowing exampleshows. During the Japanese invasion of the Malay Peninsula, the Chewong saw forthefirst flewoverthejungle.One manmettheruwai aeroplanes timeas these ofone suchplaneand itbecamehisspirit therelationship with guide,cementing of a spell. The restbecameaware of thisnew category thegift of superhumans whenthemanincludeda description of theencounter in hissong. The songs thenare innovatory whereasthe mythsare static.One presents new knowledge, the other preservesthe old. The eventsof the mythsare placed outside historically experiencedtime, those of the songs withinthe in thepast' (Cohen I969: 349), so songs As 'mythanchorsthepresent present. intothefuture. projectthepresent can be said to be interactive; The songs and myths theybuildon each other's content.Withoutthe myths,and the first laid down in them,the principles songs would have no material.The imageryused, and the premissesgiven, derive largelyfromthe myths.But the information about the superhuman worlds providedin the mythsis not verydetailed.They are, as it were, the skeleton ofChewong knowledge,andthesongswithalltheir richdetailprovide The storeofdetailed theflesh. knowledgeis constantly beingincreased through the songs. Conversely,one must assume that much detail is lost with the of songs. I regardit as quitelikely,however,thatthere is also a disappearance in the opposite direction, with detailsintroduced in the flow of information intonew myths. This goes againstreceivedwisdom songs beingincorporated thestatic nature ofmyths, I have butone whichI find concerning unconvincing. heard eventsbeing relatedabout living,or recently dead, individualswhich of a mythand whichincorporated conform to thestructure muchinformation about the non-humanworlds. Such storieswould be unlikelyto obtain the statusof 'traditional involvedare long since knowledge'untilall thecharacters So as new knowledgebecomesgenerally availablethrough dead and forgotten. is no reasonnotto assumethat itis included in new myths. The thesongs,there

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

go

SIGNE HOWELL

a process of continual relationship between mythsand songs is, therefore, ofknowledge. negotiation d. Form.Closely connectedto the contentof these categoriesof formalised The first and most obvious speech is the formin which theyare presented. areproseand songsarein verseform. These areliterary difference is thatmyths is made by theChewong-though termsimposed by me; no such distinction between the two modes. The prose they appreciatethe formaldifferences of a mythis thatof ordinary of a narrative speech. There is an introduction itsdevelopment and itsconclusion.The narrative flowsin a consecutive theme, eachactandeventleadslogically on to thenext.In terms manner; oftheir formal foundin all partsof theworld. layout,Chewong mythsare similarto myths Furthermore, thevocabularyand syntaxused are thoseof ordinary language. and rhyme The songs,however,are 'poetry':rhythm play a largepartin their thanthoseofordinary thesentences are muchshorter construction; speech;the thanon precise is often syntax different; they relymoreon imagery description; forformal are frequently inserted reasonsrather and meaningless interjections whichis marked and thanthoseofmeaning.Songs,however,havea beginning in all. It consists discernible of invocations to spirit conforms to clearpatterns of thesongs is guidesand dead 'shamans'to listenand to help. The remainder to understand-not only for me but for the Chewong extremelydifficult muchofeachsongis in 'spirit who saythat or themselves language'(klugn ruwai) in a 'different and as suchit is incomprehensible language' (klugn masign), to all to whom themeaning has beenexplained butthesinger by thebeingwho gave ofsongsfrom thesong. Itis therefore notpossibleto obtainexplanations anyone otherswould claimnot to but theowner. When approachedforclarifications, A comparisonof severalsongs revealed,however,thattheyhave understand. in thekindsofthings muchin commonin their general structure, beingreferred to, and in the way in which events and superhuman beings are described. Althoughmuch of the vocabularyused was different fromthatof ordinary The collective fiction of the uniqueness speech,it was farfromidiosyncratic. of each song was nevertheless and incomprehensibility rigorously maintained, the individualistic character of songs. Songs represent therebyunderlining subjective knowledge. While the mythsflow like ordinary and very speech,the songs are tuneful enhancedby repetitions, chorusand by accompanying drums.The rhythmic, influenced roleas music,and each actualformof thesongsis therefore by their linkedto it. song is said to have a different drumming pattern e. Performance. The occasions on which mythsare told are not limitedin any be toldby anyone,they and way. Not onlycan they mayalso be toldanywhere, at any time-often when a group of people is gathered together informally. thelastmeal. At suchtimesthemenwork Typically,thisis in theeveningafter on their Visitors from blowpipesand thewomenmakematsandbaskets. nearby housesoften dropin foran houror so before goingto sleep.Then someonemay feelherself (himself)moved to tella tale'from long,long ago'. Othercommon are those when several people are engaged in occasions for story-telling

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

9I

communalworkthatrequires little physical movement. Once one talehas been told, someone else usually startsanother.Frequentlyan event of the day prompts thechoiceofthefirst myth, whenthenarrator associates theeventwith thepertinent theoccasion,itis marked pointofit. Whatever by itsinformality. is theenjoyment-of narrator The primereasonfortelling myths and audience alike.As theraconteurs havea certain amountoffreedom in theway they tellthe is some scope forindividual story, there creativity, and some individuals were openly acknowledgedas more accomplishedstorytellers thanothers.Deviations or omissions from the known sequences are, however, immediately corrected by the audience. The rendering may be interrupted at any timeto a particular clarify issue, or simplyfor someone to make a point. Children frequently breakin to pose questions,and people laugh at the actionsof the characters. a performance to a temporary Furthermore, maybe brought haltby some extraneous eventto be resumed at a later time-or not.In other words,an characterises theoccasion. easy,relaxedand informal atmosphere The performance of songs is very different. They are performed only on ceremonialoccasions. These are of threemain types:healingseancesheld in orderto retrieve ofthepatient; thelost'soul' (ruwai) funerals whenthe'ghost'of the deceased is carriedto the Afterworld; and at any othertime when the thesuperhuman Chewong feeltheneedto contact beings.Variouspreparations mustbe done beforea seancecan be held. Specialleaveshave to be gathered to decoratethehouse and providetheresting place forvisiting spirit guides.The menmakeleafcrownsand bandoliers whilethewomen decorate their facesand flower sweetsmelling upperbodies withprinted flowers designsand gather to wearin thehair.The adornments ofbothsexesmirror thoseofthesuperhuman In thesuperhuman seancecan onlytakeplace atnight. beings.A singing worlds to humannight-time and vice versa. During a performdaytimecorresponds ance all lightsand fires are extinguished and everything mustbe done in total darknessinside the house. Once the seance has begun it must continueununtildawn. As soon as one singer interrupted takes ceases,another immediately over. Throughout,a bowl of specialincenseis keptalive. The smoke fromit is an offering to thehelpful superhumans. seancethewhole community It is a communal During a singing participates. effort at establishing contactwiththesuperhuman beings.Anyonewho has a thenight, and therestaccompany song usuallysingsit at some pointduring the singer on bamboo drums and repeat each line in chorus. The interaction betweenperformer and theaudienceis bothmoreformal and moredirect than thatpertaining when myths are told. The singers cannotperform withoutthe restofthecommunity. They aredependent upon thedrumming without which is unableto leave thebody (i.e. go intotrance), theruwai andthesoundis needed to guidetheruwai backafterwards. No other form ofaudience participation may or comments takeplace. No interruptions are allowed once theactualsession has started. The musical,or rhythmical, aspectsof singing setsthesongs apart fromtheperformance of storytelling, and thisis reflected in theeffect a seance has on theparticipants. Even thougheveryone in the does not go intoa trance sense of sendingtheirruwaiout of theirbodies, the experience nevertheless seemsto have a strong emotional butdifferent', is a impact.'It is likedreaming,

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

92

SIGNE HOWELL

to drumand sing, you want to typicalcomment;or, 'once you have started in to keep goingall night'.Clearly,transformations continue.It is not difficult are do occurat suchtimes(cf.Needham I967). No sucheffects emotionalstates of the myths.These are merelydescribedas claimed for the performance used to be'. (Forfurther us abouttheway things enjoyableand 'good fortelling details about Chewong cosmology and attitudesto health and illness, see Howell I984.) seancesand souljourneying(cf. Eliade I964) I oughtto Having mentioned add that, amongtheChewong, anyonemaybecomea 'shaman'.Anyindividual witha superhuman beingandhas beengiven who has had atleastone encounter a person of esotericknowledge (putao)who has the a song is, theoretically, The individual is a passiveagentwaiting to be ability to sendout his (her)ruwai. to spirit guide. It is also possible,however,actively approachedby a potential with going into tranceand by studying seek such knowledge by frequently those whose store of esotericknowledge is larger.As some individualsare atcontacting so someindividuals arebetter the as better story tellers, recognised bothmenand number ofsongs.Although worldsandhave a larger superhuman women can-and do-obtain songs and go into trance,men seemed,during whilethewomensaw their role singing mystay,to be moreactivein individual and chorus.This, however,is not a rule,but moreof an mainlyas drummers empiricaltendency.No such sexual division was noticeableat storytelling events. andmyths of songs Summary ofcharacteristics Mythsare anonymous,but humanin theirorigin;fromthepointof view of the Chewong they exist throughtime unchangedand unchangeable;they knowledge';theyare publicly represent a large part of Chewong 'traditional and freely availableto all; theirmain characters are humanbeings performed but with superhuman beings drawn into the activities, involved in ordinary witha plot beingdevelopedin a straightforward plot; theyareprosenarratives language,vocabularyand syntax;the manner;theyare deliveredin ordinary is more importantthan the actual words and the raconteurmay storyline with; improvise up to a point;thesequencingof theplot maynot be tampered is veryinformal; audienceparticipation anytime theymay be told anywhere, The songs displayopposite and by anyonewithoutany specialrequirements. characteristics. revealedby supertheyare personally They are of thepresent; ofthat individual; they are humanbeingsto an individual; theyaretheproperty both in formand content;additionsmay be transient; they are innovatory the main characters are insertedand sequencingof the partsis unimportant; themeswithno superhuman beings;theyare a medleyof severalintertwined thevocabulary and syntax are storyline beingdeveloped;theyarein verseform; different from those of ordinaryspeech; they are reservedfor ceremonial at night;theirperformance requires occasions; they can only be performed preparationsand ritual paraphernalia;they are sung and accompanied by and audienceparticipation is formalised. drumming; Fromthepointofview ofindigenous bothgenres arevital:the epistemology

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

93

mythspropagateeternaltruthwhile the songs provide refinements and additionsto the body of knowledge. The Chewong believe thatknowledgeis absolute and finite.Through individualinteraction with 'those who know more'-the superhuman beings-it is assumedthat,over time,theChewong will amass more and more knowledgeuntilsucha timeas theywill be able to control theirlives and theirenvironment absolutely.Such a time will be characterised by theabsenceof death,diseaseand variousmishapsand 'natural catastrophes'. otheraspectsmay be associatedwiththetwo Despite whatever suchas enjoyment, there is strong genres, on their roleas perpetuating emphasis and increasing knowledge. While mythsguide everyday actions,theycannot influence events. Songs, on the otherhand, by enlisting the help of superhumans,are a mediumforaction. Spells If examined accordingto the same criteria, Chewong spells occupy an intermediate positionbetweentheothertwo formal speechcategories, incorporatingin mostinstances boththeir characteristics. First, however,a moregeneral point will be made concerning theplace of spellsin Chewong ideology. This links directly with the finalinterpretation of theirrelativeplace in the total discourse. Unlike the myths,and much more thanthe songs, the spells are associated with specificpurposes, namely to controland to dispel harmful interference bynon-human beings.As suchthey areused byhumans in orderto maintain, andrestore, theboundaries between humanexistence andnon-human existence. Any uncontrolledmixing of elementsfrom different spheresis invariably harmful.The spells can eitherpreventsuch occurrences at times whenthesemight be expected, or restore thebalanceafter they havetaken place. Spells are utteredonly at times when humans need to protectthemselves. Typically theseare(a) attimesofillness whentheright spellcannegatetheeffect of the non-humancause; (b) at life crisessuch as birthand death; and (c) whenever theChewongfind themselves inlocations orsituations whereharmful or might beingshave attacked, be expectedto do so. a. Origins anddurability. Thereare two ways in whichspellsbecomeknownto an individual.Some spells are, like myths, timelessand regarded as 'original knowledge'. No one knows who first came by them.These spellsare passed fromperson to person. Other spells,like songs, come into existenceas gifts froma person's spiritguide. If theseare handed over to someone else, they eventuallybecome part of the traditional body of knowledge. Spells thus preserve old knowledgeand are a mediumforintroducing new; theyare both static and innovatory. b. Ownership. Spells are the personal and exclusiveproperty of those who studiedthemor were giventhem.To be givena spellby someone involvesa procedure which(in Chewong terms) is fairly complex.The personwishingto learn must approach the possessor of the spell and formally requestit. The 'teacher'spends enough time with the 'student'to ensurethats/hehas fully

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

94

SIGNE HOWELL

hands over a giftin return learntit, at which point the student forthe spell. of spellsis not possiblebecauseof theway theyare performed Casual learning (see below). All thespellsthatI came acrossfallintotwo distinct c. Content andform. parts. of a narrative The first partconsists abouta humanbeinginvolvedin his or her This sectionis told in ordinary daily activities. descriptive language.There is some development ofa theme.The secondpartis in rhythmical verseform. The and repetitions. The oral narrativeis abandoned in favour of statements ofa spellchangesdramatically presentation from a slow, conversational tonein recitation in thesecond. Also, thechief thefirst partto a muchmorerhythmic characters become superhuman and beings(thosewhom thespellcan control), much of the vocabularyceases to be that of ordinary speech and becomes as in the songs. Indeed, the people who gave me theirspells only 'different' them.This contrasts withthesongswhichtheownercan understood partially To be efficacious, a spellmaynotbe changedin anyway. Neither understand. are allowed, the additionsnor subtractions may be made. No improvisations utterance of a spell must be in completeconformity with its originalstate. attributed Failureof a spellto achieveitspurposeis frequently to ithavingbeen within some way. Those who know spellspractise themwhenalone tampered forfear offorgetting anypartofthem.Theirpowerdoes notdependupon their being understoodbut in theirbeing utteredcorrectly. Thus, possession of in spells-is demonstrated knowledge-as represented byknowingwhatto say regardlessof understanding. Chewong spells are an example of words as as actors,not as meaningmakers.A similar objects,or rather pointis made by Peek in hisdiscussion ofAfrican 'verbalarts'whenhe says,'thepowerofwords is not merelyan abstract concept.We findmanyAfrican societiesresponding to verbalart.Wordscan affect veryliterally their speaker, and thespeaker must takeprecautions to guardhimself from theadverseeffects ofthewords' power' (I98I: 37). This is an important pointto whichI shallreturn later. mediumforcontacting thespirit in an Songs arethechief guidesandengaging withthemwhichsometimes activerelationship leads to thesinger the entering worlds. The spells,whilefocussed superhuman upon thesuperhuman worlds, not a mediumforcontacting membersof thoseworlds. The are nevertheless utterance of thespell. desiredpurposemay be achievedsimplyby thecorrect state ofconsciousness. The speaker does notseekan altered unlike Furthermore, the all-purposesongs, each particular occurrence (illness,mishap,actual and has itsown spell. Throughsinging and souljourneying, a potential calamities) aim suchas invoking a cure.Thereis, some specific personmaybe able to effect however, no guaranteeof this. The singeris at the mercyof all kinds of whichmayfrustrate ofthecorrect unforeseen adventures theaim. The utterance obtainsresults.The problemis one of possessingthe correct spell inevitably spell. d. Performance. The performance of spells reflects theirspecificteleological An integral ofsongsand legendsis audience character. partof theperformance The performance ofa spell,on These areoccasionsfor participation. enjoyment.

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

95

the otherhand, takes place in isolation. In the case of illness,the operative relationship is that between speaker, attackerand patient. In the case of protective measures,it is betweenthespeakerand thepotential attacker. The restofa Chewong community usuallyknowswhenever someoneis performing a spell,butthey remain unconcerned sincethey haveno roletoplay.Besides,the performance ofa spelloffers no enjoyment. Itis uttered ina semi-audible rapidly whisper.Nobody shouldoverhear it. While the actual performance of a spell is separatedfromthe community, thoseon whose partit is uttered nevertheless have certain obligations.These come into effect both beforeand after theperformance. Various prohibitions (pantang) whichdiffer to spelland purpose,mustbe observed.In the according case of a sick person,thepantang apply only to him or her,althoughin some casesrelatives thewhole community is atrisk, maybe involvedalso. Whenever suchas attimesofdeathorimpending 'natural' catastrophes, everybody present has to observethem.Hence, despiteappearances to thecontrary, theperformance of a spelldoes have widersocial significance. Unlike a singing seance,the of a spell requires no ritualobjectsor acts,although performance a performer will frequently employincensesmoke, and occasionallywaterand leaves for rubbing thebody of a patient. These aresupplementary to the aids,notintegral utterance of spells.The spellsmustbe performed either at dawn or dusk,i.e. at thetransitional pointsbetweennight and day;or at timesspecifically designated by thecontext. Withregardto most criteria, it has emergedthatChewong spellsdisplaya ofsongsand legends.They thusgenercombination of theopposingattributes ally occupy a medianpositionbetweenthe two extremes.In a few instances an overlap withjust one of the othertwo, as in the case of spells manifest ownership (see fig. i). Conclusion The range of attributes associatedwith the threegenresof Chewong formal intonoticeable speechactsfalls patterns whichwould nothaveemerged had one notlooked at all thegenres in relation to eachother. The first pointto noteis that two ofthecategories, namely songsand myths, consistently appearto represent two sets of opposing positions. Secondly, most spells appear to combine characteristics fromthe two extremepoles. As such theyoccupy a median a synthesis position.They constitute of attributes in Chewong formalpresent ised languagegenres.To accountforthisI return to Chewong epistemology, and the cultural values associatedwithit. I have arguedin thisarticle thatthe three offormal in Chewongsociety genres areregarded speechactsfound bythe as constituting a related Chewong themselves setofphenomena. People explain each in termsof either, or both, theothertwo; theyexplicatesimilarities and I haveavoidedanydiscussion differences. So far ofrelative value. Itis, however, that a superior valueis attributed unquestionable to spells.To be thepossessorof a large numberof spellsis more desirablethanknowingnumerousmythsor thisvaluelies. Itis notbyvirtue songs. The questionthenariseswherein oftheir entertainment Both songs and value, or fromany aestheticconsiderations.

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

96

SIGNE HOWELL

myths score higheron thesecounts.It is, I would argue,withintherealmsof that theanswermaybe found. toknowledge, andattitudes knowledge(haeraten) to theChewong to be able to understand (haeraten) It is ofutmost importance is thefirst theirenvironment. steptowardscontrol.It will be Understanding a co-extensive remembered thatenvironment, societyand cosmos constitute of order.To be able to maintain based on identical order, universe, principles of vitalconcern.This is it wheneverit is upset,is a matter and to reestablish achievedby knowingabout theuniverseand its workings.Mostlyit is learnt the spells-which confer littleknowlfromsongs and myths.Paradoxically, behaviourwithinit-represent the edge about the universeand appropriate is seriously kind of knowledge. Wheneversomething wrong, most effective thenthe surestway to set it rightis to know the appropriate spell. Knowing is stilltheoperative (haeraten) word; butin thecase of spells,notknowinghow and/orwhy, but knowingwhat-what thatis, to say. Withtherightspell at is This attitude one's disposal,a personmay, in theory, accomplishanything. 'shamans'arethosewho, to be able to act in assertions thatthegreatest reflected upon the world, have no need of singingseanceswith theirassociatedritual to people who attained their is fullofreferences The mythology paraphernalia. ofa spell. esoteric goal simplyby theutterance This raisesa pointmadebyTambiahinhisre-examination ofTrobriand spells ofhis argument, as I see it,is to demonstrate (Tambiah I968). The mainthrust to thecontrary, spellsarenot meaningless that,despiteMalinowski'sassertion neither thespeaker, therestofthecommunity, jumbles ofwordswhichinform nor the anthropologist about a wider discourseof meaning.He suggeststhat Malinowski and others have elevated the importanceof the word to the ofritual, exclusionof another vitalingredient namelyaction.All ritual mustbe the manipulation of examinedas a 'complex of words and action (including oftheir interconnexion mustbe demonstrated objects)' (I968: I84). The nature to establishthe 'innerframe'of magical behaviour,the 'semanticsof ritual' betweenmetaphoric and themeton(I968: I88). Using Jacobsen'sdistinction an analysisof certain Trobymic operationsin language,Tambiah performs riandspellsand their associated ritual objectsand deeds,and I haveno hesitation in agreeingthatour understanding of Trobriandspellshas been enriched, and thatthere is indeeda system ofinterlinking ideasunderlying their performance. Malinowski's assertion thatTrobriandspells are 'an exceedingly obscureand of ideas' is not vindicated. confusedconcatenation Does thisanalysisdemonthanbeingconfused byverbal strate, however,that'thesavagemind. . . rather or acting in defiance fallacies ofknownphysical laws,itingeniously conjoinsthe of languagewith the operational and expressiveand metaphorical properties of technical (I968: 202)? In otherwords, is there empirical properties activity' betweenwordsand actions? alwaysan interconnexion It would appearfrom ofChewong formal speechactsthatthis myexposition is notnecessarily so. Chewong spellsdo notconform to Tambiah'sdefinition of of a spell may involvetheutilisation of ritualobjectsand ritual.The utterance but as we have seen,theseareminimal. whenever Furthermore, they activities, arealwaysthesameonesandhencethedegreeoffit areemployed,they between in anydeepersense(the'inner thetwo modesofexpression is likely frame') to be

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

97

trivial.But, more importantly, theultimate power of a spelllies in thewords alone. Not only are deeds and objectsresorted to onlyby theless knowledgeable, but the words may in factbe mumbo-jumboto everylivingChewong, althoughpossiblynot to the superhuman being whom theyare intendedto I am in agreement affect. In thislastrespect, withTambiahwhenhe saysabout in 'demon language',they theSinhalesemantra that,although theyarelargely 'do notfalloutsidetherequirements oflanguageas a system ofcommunication' (I968: I78). We are more likely to be successful in an examinationof the relationship betweenthewords employedin a Chewong song and theobjects and actionsof a singing seance. It mustbe bornein mind,however,thatwhile thesongs change,therituals themdo not. The objectsand acts accompanying in all instances oftheintention are,moreover, identical oftheseance. regardless From one perspectivethere is a strong intentionality associated with in spells. In Chewong formalised speechwhich findsits strongest expression ofknowledge(haeraten), oftheformal terms generated by each category speech acts,we findthattheydiffer widely. Mythssupplytheknowledgeof and the knowledgefor,thereby theframework formeaningful humanaction. creating Whiletheyareconstitutive, arenotinstrumental in achieving action.They they embodyknowledgewhich,ifadhered theChewongfrom committo,prevents tingacts or thoughts whichwould lead to illnessor mishapof variouskinds. Thereis thusa preventive The knowledgegivenin themis, aspectto themyths. however, farfromexhaustive,and the Chewong are fullyaware thattheir controlover themselves and theirenvironment is limited,and thatthingsare likelyto go wrongfrom timeto time.Songs area majormeansforcopingwith illnessand mishapsonce theyhave occurred.They are also theonly meansat their intoactiverelationships withthesuperhuman disposalto enter beings,and theseencounters, bothto increase their andto enlist thehelp through knowledge of thesuperhumans. in so Songs areconstitutive (and by extension preventive) faras theymay providenew information leadingto increased understanding. in so far as they are the means for requesting They are also instrumental intervention by superhumanbeings. Things may be put rightthroughthe ofsongs. performance are both instrumental and preventive, but in Spells, while not constitutive, theother different two genres. significantly waysfrom to Theyareuseddirectly and avertdangeras well as to remedy itseffects and to obtainspecific prevent forachieving objectives.The spellsarepurelymechanisms desiredends. They do notinvolvethesuperhuman in contained beings,and theactualinformation themhas no reference or usefulness outsidethecontext of theutterance of the of the threegenresof formalised spell itself.They are the most efficacious the world and speech. Whereasboth mythsand songs are about describing humansto actproperly within through description helping it,and songscan be used to change misfortune, the spells are exclusivelyabout actingupon the world. Justas the spells combine both means forprevention and cure, thus and songs,theyalso combinemostof thecharacteristics synthesising myths of thesetwo. Thereis therefore a congruence betweenthetwo setsofrelationships -both on thelevel of thought and action.Whereasfromthisperspective the spells can, however, be seen to stand in a median position, fromanother

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98

SIGNE HOWELL

in oppositionto the thesongs and spellsmay be classedtogether perspective, in achieving action.Thus, from thepointof myths. They arebothinstrumental while both songs and view of what each genredoes, the mythssimplystate, ofsuperhuman actiononlywiththeintervention spellsdo. But songs can effect beings, whereasspells act on theirown. The highervalue attachedto spells forcontrolled ofknowledgeas a mechanism theframework makessensewithin action. each genre is speechactsas a totaldiscourse, all Chewong formal By treating with all the others. understoodmore richly, being viewed in its relationship knowledge,but achievesitsparticular Each does not standalone in expressing to therest, andtheir overallplacein thecosmology. identity onlyinrelationship

NOTES

Fieldworkamong the Chewong was carriedout between I977-79 and was supportedby the Social Science ResearchCouncil. A return visitin I98I was made possibleby the SusetteTaylor TravellingFellowship I98I-82 awarded by Lady MargaretHall, Oxford; and by a grantfrom Sociale: Morphologie,Echanges(CentreNational de la Equipe de la Recherched'Anthropologie ofthispaperweregivenat seminars attheLondon Recherche Scientifique, France).Earlierversions School of Economics and theInstitute of Social Anthropology, Oxford. I thankthosepresent for I also wishto thank comments and criticisms. for their RodneyNeedhamandAndrewDuff-Cooper I am particularly to thetwo anonymous reading earlier drafts. grateful referees to Man who, whenI forconsideration, submitted my originaldraft pointedout the lacunae in my knowledgeof the ofspeaking.Roy Willisand Alan Campbellkindly oftheAmerican readmy literature ethnography comments. Finalresponsibility revisedversionand made severaluseful is, of course,myown. 1 In Britain, variousexpressions havebeenused to discusswhatI am terming formal speechacts. I find is a commonly found inprecision, 'Oral traditions' so since one, butone that lacking especially on theexpression insists 'oralliterature' whichI would suggest itimpliesthepastonly. Finnegan is a in terms.Willishas coined 'spoken art'; and 'verbalart' and 'oral art' are yetother contradiction withthelast threeis in theemphasisplaced on art.This conceptis far variants.My disagreement in evaluativeassessments fromunproblematic, and its usage involves the anthropologist of the various genreswhich, I would argue, lies outsidehis or her competence.In Americathe term 'folklore'is in current use but this has derogatory overtonesin Britishanthropology. For my formal purposes,theexpression speechacts avoids theabove problems.It is derivedfromSearle, oflanguageis partofa theory ofaction, 'Speakinga languageis performing speechacts. . . a theory form ofbehaviour'(I968: I6/I7). simplybecausespeakingis a rule-governed 2 'Long ago' in Chewong usage simply meansthatperiodpriorto whatmaybe calledindividual historical time,i.e. thelifetime of thepersonconcerned, or thatof identifiable relatives extending back rarelybeyond two or threegenerations.No temporaldistinctions are made betweenthe myths, theyall represent eventswhichoccurred 'a long timeago'. 3 It maybe pertinent thepositionofChewong linguistic hereto clarify status and itsrelationship with Malay. While Malay is an Austronesian language, Chewong belongs to the Mon-Khmer of the Austro-Asiatic no relationship family languages. Formally,thereis therefore betweenthe two. Contactbetweentheaboriginal people and Malays has, however,probablytakenplace since thetimeofearlyMalay settlement ofthePeninsula(c. 2000 yearsago), and manyMalay loan words havebeenincorporated intoall theaboriginal languages, including Chewong. Most adultChewong canspeaksome Malay. Itis extremely difficult to explainwhysome wordsandnotothers havebeen wherea word (signifier) adopted. I foundthatin most instances had been absorbedthe meaning had undergone some transformation. (signified) of essaysincludesin its bibliography 4 This collection reference to only two works on recent American folklore studies(cf.my comments on British lack ofawareness). 5 I use theterm 'shaman'reluctantly. The term in Englishhas substantive connotations denoting a discernible of people. This does not reflect theChewong situation. In Chewong usage, category

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

99

to a nounor a verb.Thus theywillsay 'he is aputaoman' in is notso mucha nounas a qualifier putao man'. thesameway as theywould say 'he is a strong

Appendix

is complete, the songsand spells.Whilethemyth The following areexamplesof Chewong myths, butitis hopedthat they aresufficient to from thecomplete texts, songandthespellarebothextracts it is, of illustrate themainpointsthatI have made withregardto formand content.In translation is 'different' whether thevocabulary or ordinary. Fora rendering course notpossibleto demonstrate of a completesong in both Chewong and English,see Howell I984; and fora mythin Chewong examples see Howell I 982. Fromthepointofview ofrecording witha word-for-word translation, weretheeasiestto obtainand the speechacts,themyths ofthedifferent genresofChewong formal in thearticle. I was given This conforms to their relative value as discussed spellsthemostdifficult. ofseclusion.I was permitted to record visitin I98I andunderconditions spellsonlyupon myreturn a few,however,and theownerexplainedthemto me. The songswerealso recorded.I transcribed forthe from theowners.I didnotuse a taperecorder themas bestI could and obtainedclarifications and also willingto tellthe butreliedupon my 'mother'who was one of thebestraconteurs, myths, sametalerepeatedly. with Myth:'Siamang binturong' (I) a siamangand a binturong. He put A manwenthunting withhis blowpipe. He shota leafmonkey, in hisbackbasket and wenthome. On theway he saw a tiger. Whenhe arrived atthe allthree animals swidden he gavethemeatto hiswifeto cook. Theyall atethethree meats,buttheman'sunclewould not eat the binturongtogetherwith the siamang. He was a shaman man. He was afraidof In thenighteveryoneclimbedtreesto sleep in. They were frightened a committing tigertalaiden. hisblowpipewithhim.Duringthenight he kickeditandit come. The nephewbrought tiger might fellto theground.'I am going down formy blowpipe' he told his wife. 'Oh, but whatabout the tiger?' said she. He took no notice and climbeddown. Justbeforehe reachedthe groundhe felt arelotsofthorns!' he exclaimed, claws. hislegs. 'Hey, there butitwas thetiger's something scratch and theman died. 'I'll sleep in the The tigerwas waitingforhim. The tigerbit him at thethroat, to be herhusband.The housefortherestof thenight',thetigercalledout to thewife,pretending to climbthetree in which tiger atethebody and theblood, buthe did noteatthehead. He thentried at the theuncleand hisfamily weresleeping,buthe could not do so fortheunclehad placeda knife bottomofthetrunk and uttered spellsoverit. a long-tailedmacaque and a The next day the uncle went hunting.He shot a leafmonkey, hisuncle's The headofhisdead nephewfollowedhimthewholeday. He wantedto capture squirrel. ruwai, buthe could not do so fortheunclehad said spells. In the eveningthe uncle went home. The head of his nephew followed.The uncle made leaf in a singingseancefor headbandsand plaitedleaves to decoratethe house. Everyoneparticipated At theend of theseventh sevennights. seance,theghostof thedead man was expelled2. ' Thereis a rulethatforbids is alwaysan attack themixingof thesetwo meats.The result by a talaiden. tiger: tiger 2 Here bothspellsand songsare employed.The uncledid nothave theappropriate spellto expel seance. theghost,so he had to makea singing Mount Song:'Bongsofrom Nynyed' ... Not easy. All theramei friends (fruit) go. Soleraw leaves(shaman'swhisk),sono(leaves) fromNintjar. Ah, mist(like)sono(leaves) in theeyes. in thehair)! on thebody)! See thechinur (flowers Chachag (flowers batheunderthespray. We batheunderthewaterfall, We batheunderthewaterfall. Walkaboutin thespray,walk about. Amoi! Ahoi! . . . bas(a species superhuman being) Spell:Against ofharmful and he got lost. Tell ofhow he wentover there.He wentoverthere him. He came to a house. It was thehouseof He gotlostoverthere.Some people followedafter hismother and father.. ..

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ioo

SIGNE HOWELL

... Theyhit,theyhit. Theysayspells-they frustrate us. Underfallen treetrunks we stab-they frustrate us. Theyshootus-they frustrate us. We stabat thewaist-they frustrate us. We stabin thestomach-they frustrate us. We stabin theback-they frustrate us. . ..

REFERENCES

in thedefinition offolklore. In Towards Abrahams, R. D. I972. Personalpower and socialrestraints new perspectives infolklore (eds) A. Paredes& R. Bauman. Austin:Univ. ofTexas Press. in St Vincent.In Folklore: andcommunication performance I975. Folkloreand communication (eds) D. Ben-Amos& K. S. Goldstein.The Hague: Mouton. of nonsenseon St Vincent. I982. Storytelling events:wake amusements and thestructure J.Am. Folki.95, 389-4I4. of speaking.Am. Anthrop. 66, Arewa, E. 0. & A. Dundes I964. Proverbsand the ethnography Suppl. Dec., 6 pt. 2, 70-85. Bauman,R. & N. McCabe I970. Proverbsin an LSD cult.J.Am. Folkl.83, 3I8-34. inthe &J. Sherzer Cambridge:Univ. Press. (eds) I974. Explorations ethnography ofspeaking. Am. Anthrop. I975. Verbalartas performance. 77, 290-3 II. andcommunication and his audience. In Folklore: performance (eds) Basg6z, I. I975. The tale-singer D. Ben-Amos& K. S. Goldstein.The Hague: Mouton. of folklore in context.In Towards newperspectives in Ben-Amos, D. 1972. Towards a definition folklore (eds) A. Paredesand R. Bauman. Austin:Univ. ofTexas Press. Am. Folk.89, 249-54. I976. Solutionsto riddles.J. The Hague: Mouton. andcommunication. & K. S. Goldstein(eds) I975. Folklore: performance andoratory intraditional London: AcademicPress. Bloch, M. I975. Political language society. Cohen, P. S. I969. Theoriesof myth.Man (N. S.) 4, 337-53. De Heusch,L. I982. Thedrunken king. Bloomington:IndianaUniv. Press. New York: VintageBooks. Douglas, M. I973. Natural symbols. Dundes, A. I964. Texture,text,and context.S. Folkl.28, 25I-65. ofTurkish boys' verbaldueling rhymes. ,J.W. Leach& B. Ozkok I970. The strategy J. Am. Folkl.83, 325-49. archaic London: Routledge. Eliade, M. I964. Shamanism; techniques ofecstasy. andstorytelling. Oxford:ClarendonPress. Finnegan, R. I967. Limbastories to thestudyof oral literature in British social anthropology. Man (N.S.) 4, I969. Attitudes Oral literature inAfrica. Oxford:ClarendonPress. itsnature andsignificance. Oralpoetry: Cambridge:Univ. Press. Fox, J.J. I974. Our ancestors spoke in pairs: Rotineseviews of language,dialects,and code. In in theethnography Explorations ofspeaking (eds) R. Bauman andJ. Sherzer.Cambridge:Univ. Press. Goody,J. I977. Thedomestication ofthe savagemind. Cambridge:Univ. Press. and legends Howell, S. I982. Chewong myths (Monogr. R. Asiat. Soc. II). Kuala Lumpur:Royal AsiaticSociety. andcosmos: I984. Society Chewong ofPeninsular Malaysia.Oxford:Univ. Press. of speaking. In Anthropology and humanbehaviour (eds) Hymes, D. I962. The ethnography T. Gladwin& W. C. Sturtevant. Society. Washington: Anthropological inculture andsociety. New York: Harper& Row. I964. Language of languageand social setting. J. socialIssues 23, (2), 8-28. I967. Models of theinteraction in sociolinguistics; the (Revised versionIn: J. J. Gumperz & D. Hymes (eds) I972. Directions New York: Holt, Rinehart ethnography ofspeaking. & Winston.) into performance. In Folklore, and communication (eds) I975. Breakthrough performance D. Ben-Amos& K. S. Goldstein.The Hague: Mouton. of statusmanipulation in the Wolof greeting. In Explorations in the Irvine, J. I. I974. Strategies ethnography ofspeaking (eds) R. Bauman andJ.Sherzer.Cambridge:Univ. Press.

I970. I977.

59-69.

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SIGNE HOWELL

IOI

Kirk,G. S. I970. Myth:itsmeaning & other andfunctions inancient cultures. Cambridge:Univ. Press. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. I975. A parablein context: a social interactional analysis of storytelling and communication performance.In Folklore:performance (eds) D. Ben-Amos and K. S. The Hague: Mouton. Goldstein. Leach, E. (ed.) I967. The structural and totemism: study of myth (A.S.A. Monogr. 5). London: Tavistock. as myth I969. Genesis andother London: Cape. essays. & D. A. Aycock. I984. Structuralist interpretations ofBiblical myth. Cambridge:Univ. Press. C. I963. The structural Levi-Strauss, studyof myth.In Structural anthropology. Harmondsworth: Penguin. I970. Mythologiques 1: Therawandthe cooked. London: Cape. toashes.London: Cape. I973. Mythologiques 2: From honey I978. Mythologiques3: Theorigin oftable manners. London: Cape. man.London: Cape. I98I. Mythologiques 4: Thenaked andtheir vol. 2. London: Allen& Unwin. Malinowski,B. I935. Coralgardens magic, andreligion andother Boston: psychology.In Magic,Science essays. I948a. Mythin primitive Beacon Pr. (Originally publishedI926). andreligion andother society.In Magic,science I948b. The problemof meaningin primitive essays. (Originally publishedI923). Boston: Beacon Press. Needham,R. I967. Percussion and transition. Man (N. S.) 2, 606-I4. Peek,P. M. I98I. The power ofwordsin African verbalarts.J.Am. Folkl.94, I9-43. Propp, V. I958. Morphology of thefolktale.Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Research Centre in Folkloreand Linguistics. Anthropology, Salmond, A. I974. Rituals of encounteramong the Maori: sociolinguistic studyof a scene. In in theethnography Explorations ofspeaking (eds) R. Bauman & J. Sherzer.Cambridge:Univ. Press. Searle, J. I968. Speech acts.Cambridge:Univ. Press. Tambiah,S. J. I968. The magicalpower of words. Man (N. S.) 3, I75-208. Toelken,B. I975. Folklore,worldview,and communication. InFolklore:performanceandcommunication (eds) D. Ben-Amos & K. S. Goldstein.The Hague: Mouton. and beyond.Man (N.S.) 2, 5I9-34. Willis,R. I967. The head and theloins:Levi-Strauss wasa certain man:spoken artofthe I978. There Fipa. Oxford:ClarendonPress. A statein themaking: I98I. myth, history, and social transformations in pre-colonial Ufipa. Bloomington: IndianaUniv. Press.

This content downloaded on Wed, 16 Jan 2013 14:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- National Art Education AssociationDocument3 paginiNational Art Education AssociationPedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Language of LegislationDocument25 paginiThe Language of LegislationPedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lexical PragmaticsDocument48 paginiLexical PragmaticsPedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Operationality of Grices Test For ImplicatureDocument8 paginiThe Operationality of Grices Test For ImplicaturePedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interpreting Anaphoric Expressions A Cognitive Versus A Pragmatic ApproachDocument41 paginiInterpreting Anaphoric Expressions A Cognitive Versus A Pragmatic ApproachPedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conversational Maxims and Some Philosophical ProblemsDocument15 paginiConversational Maxims and Some Philosophical ProblemsPedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phoronography and Speech ActsDocument21 paginiPhoronography and Speech ActsPedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)