Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Different Schools of Unemployment by Siyaduma Biniza

Încărcat de

Siya BinizaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Different Schools of Unemployment by Siyaduma Biniza

Încărcat de

Siya BinizaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Unemployment According to Neoclassical, Monetarist, Keynesian and Marxian Economics

Written by Siyaduma Biniza* Addressing and analysing unemployment is a central issue in economics. Hence neoclassical, monetarist, Keynesian and Marxian schools of economic thought have all sought to contribute to the literature on the subject. However, even though the challenge of unemployment is centrally related to wages and firms profitability, each school offers a distinct understanding and analysis of unemployment based on each schools theoretical framework. Neoclassical and monetarists argue that

unemployment is a consequence of market imperfections caused by government and trade union interventions; which results in wages above the equilibrium wage. Whilst Keynesians argue that unemployment is a consequence natural consequence of wellfunctioning markets which result in business cycles due to firms investing in uncertainty. Whereas Marxian economists argue that unemployment is a consequence of technical change and class struggle between workers and capitalists. Thus, this essay compares and contrasts the relevant theoretic foundations and explanations for unemployment. Unemployment for Monetarist and Neoclassical Economics The neoclassical and monetarist explain two types of unemployment, namely, voluntary and involuntary. Voluntary unemployment is a result of workers not accepting the equilibrium wage (Friedman, 1968). The equilibrium wage is the real wage determined by equilibrium in goods, labour and capital markets known as the Walrasian or general equilibrium (Pollin, 1998). Since the labour market is in equilibrium when all workers accept this wage, labour supply equates to labour demand. This means that unemployment is zero, adjusting for frictional

unemployment, when all workers earn their equilibrium wage (Pollin, 1998). Further, when all workers accept the reservation wage, unemployment can be zero or at its equilibrium rate known as the natural rate of unemployment. The natural unemployment rate is a consequence of the general equilibrium which dictates the equilibrium wage (Friedman, 1968; Tobin, 1972). Therefore, unemployment rates signal whether there is excess demand or supply in the economy depending on how the real unemployment rate compares to the natural rate of unemployment (Friedman, 1968; Stein, 1981). Thus, workers can voluntarily reject the reservation wage and choose to spend their time on leisure or other activities; resulting in voluntary unemployment (Pollin, 1998). However, neoclassical and monetarists are not really concerned with voluntary unemployment. Their focus is on involuntary unemployment because it represents a failure of the markets equilibrating inclination. Therefore the focus is on how the real unemployment rate can be affected by trade unions bargaining and government interventions; which result in higher real wages (Friedman, 1968; Pollin, 1998; Tobin, 1972). Trade unions can interfere in the labour markets through collective bargaining driving the real wages above the equilibrium wage. Whereas government can intervene by passing legislation to set a minimum wage that exceeds the equilibrium wage. As a consequence of any, or both, of these interventions the supply of labour would increase since the real wage has risen above the reservation wage. But the demand for labour would decrease since the demand for labour decreases as the cost of labour increases. This would result in disequilibrium in the labour market, with supply exceeding demand, and unemployment would exceed its natural rate causing involuntary unemployment. (Pollin, 1998). Thus, unemployment is voluntary when workers reject the equilibrium wage or involuntary due to market imperfections caused

by government and trade union interventions resulting in real wages that exceed the equilibrium wage.

However, the market imperfections can only cause short term changes to the real unemployment rate because the economy will equilibrate through relative changes in prices and nominal wage which drive down the real wage in the medium term and long term (Stein, 1981). Consequently neoclassical economics asserts that full employment is attained, without government intervention, through market mechanisms such as price adjustments, flexible wages and interest rate resulting in the general equilibrium in the long run (Forstater, 2000). The basic idea is that, starting from a situation where there is higher supply of labour than demand; competition between firms will iteratively drive down real wage increasing the demand for labour until equilibrium is reached (Hillier, 1991). Thereafter, output and income would have increased. But, since some of the newly employed workers save some of their income, savings would exceed investment leading to decrease in the interest rate in the capital market; which reduces savings and induces demand for loans and increases investment until equilibrium between savings and investment is reached (Hillier, 1991). Therefore economic shocks, such as low aggregate demand for goods, work through mechanisms such as flexible wages and instantaneously adjusting prices resulting in the general equilibrium and full employment in the long run. However, Keynesians criticise this analysis asserting a vastly different theory. Unemployment for Keynesian Economics Keynesians argue that savings are a function of income and that investments depend on expectations under uncertainty rather than savings (Forstater, 2000). Firstly employment and output are determined by aggregate demand which determines on investment depending on firms expectations about future profitability (Amendola et

al., 2004). Furthermore, incorrect expectations may result in co-ordination problems that affect capital market equilibrium between savings and investment (Amendola et al., 2004). Therefore interest rates, which determine financial market equilibrium, do not equilibrate savings and investment (Amendola et al., 2004). This is because savings and investment have vastly different determinants, i.e. income and expectations about profitability. Thus savings, which are a function of disposable income, do not determine investment since investment decisions depend on firms expectations under uncertainty. Moreover equilibrium in the capital market is challenged by co-ordination problems between savings and investment; instead of financial market equilibrium between interest rates and money (Amendola et al., 2004). This means that low aggregate demand may lead to low expectations and low investment which results in low output and involuntary unemployment. Therefore, even though interest rates may adjust to aggregate demand changes, investment may be unaffected because interest rates have far less effect on aggregate demand and firms expectations about future profitability (Stein, 1981). This is due to the co-ordination problem of savings and investment so interest rates might have a strong effect on savings but only an indirect, and lesser, effect on aggregate demand. These unequal effects on savings and investment are the source of the co-ordination challenge of savings and investment. Therefore, even under perfectly functioning markets involuntary unemployment would exist. Moreover, given that firms make investment decisions based on expectations under uncertainty, firms may have incorrect expectations which exacerbate the coordination problem between investment and savings; leading to involuntary unemployment (Amendola et al., 2004). Thus, involuntary unemployment is a

consequence of well-functioning markets and there is no market mechanism to ensure full employment (Wray, 2011). Furthermore, Keynesians argue that wages are not flexible and that it is money, or nominal, wages that matter instead of real wages (Leontief, 1936). Firstly, Keynesians argue that the bargaining outcomes do not determine real wages but they determine the nominal wage. Therefore, workers are liable of accepting a decrease in real wages that might result due to an increase in the price levels; but workers are more responsive to nominal wages and they would resist (Leontief, 1936). Thus involuntary unemployment is a consequence of well-functioning markets and firms investing in uncertainty; instead of real wages. Moreover, under imperfectly competitive conditions, even though the co-ordination problem between investment and savings can be solved; involuntary unemployment would still persist due to trade union bargaining influence (Amendola et al., 2004). Therefore involuntary unemployment is a natural feature of capitalism because investment decisions are made under uncertainty. So Keynesians argue that markets do not return to full employment by themselves and that involuntary unemployment is a characteristic phenomenon of capitalism (Wray, 2011). Thus, unemployment is a natural feature of capitalism due to uncertainty and business cycle which necessitates government intervention to stimulate demand during slumps and eliminate unemployment (Forstater, 2000). Unemployment for Marxian Economics Marxian economics would be in agreement with Keynesian economic that unemployment is a natural feature of unemployment. However, with its entry point as the class process of society, Marxian theory emphasises something vastly different Keynesian theory; which most economic theories have overlooked.

Marxian theory explains the economy as a complex interaction between relations and forces of production. Therefore capitalism is a specific mode of production comprised of forces and relations of production (Saad-Filho, 2002). Forces of production are related to the methods of production available to labour; whilst relations refer to the class structure of under capitalism, i.e. workers and capitalists (Saad-Filho, 2002). However, even though there is no society exists with just two classes, capitalism, like other modes of production, is unique in the way that the surplus is extracted; i.e. the relations of production. The relations of labour are related to the extraction and appropriation of surplus labour. Surplus labour is labour beyond what is necessary for personal survival; which is quantified as surplus value (Wolff & Resnick, 1988). So under capitalism surplus value is the value produced by worker above the cost of inputs and the value gained by worker (i.e. wages) from selling their labour power in the market (Wolff & Resnick, 1988). However, the appropriation of surplus value is not necessary done by direct labour which produces surplus. Therefore Marxian theory defines class exploitation as the situation where direct labour is not involved in appropriation of surplus labour (Wolff & Resnick, 1988). This is known as the fundamental class process. Consequently workers are exploited by definition under capitalism since goods are sold at a profit which the capitalist keeps for reinvestment, or accumulation, or remuneration (Wolff & Resnick, 1988). Marxian theory thus emphasises that the forces and relations of production (i.e. class process) determine economic relations such as prices, cyclical change, markets and social changes (Wolff & Resnick, 1988). Thus, unemployment is crucial related to the forces and relations of production under capitalism. This means that unemployment is related to the forces of production as a consequence of technological change, an increasing labour force and capital accumulation

(Robinson, 1941). Employment is therefore determined by the capital and technology used in production. Therefore, as capital accumulates and production technology changes, some labour is displaced due to technical changes and the labour force is increasing due to natural population growth; resulting in rising unemployment and an increasing reserve army of unemployment (Robinson, 1941). Furthermore, technical change displaces labour at a rate that is necessarily equilibrated by investment and employment. Moreover, driven by competition firms always have incentive to use more productive technology results in less use of labour to increase output. Thus, unemployment can arise from technological displacement. However, when a capitalist economy grows at such a high rate that capitalists employ more labour, which reduces unemployment, workers bargaining power increases (Pollin, 1998). Therefore workers are in a position to demand higher wages which reduces the exploitation by increasing the share of surplus value appropriated to workers. But this reduces the capitalists share of the profit. So capitalists animal spirits are dampened leading them to invest less thereby decreasing job-creation, increasing unemployment and expanding the reserve army of unemployed (Pollin, 1998). Yet, as unemployment increases, workers lose some of their bargaining power and wages are driven down. In this situation capitalists are investing so as to maintain their targeted profitability which results in higher unemployment decreasing workers bargaining power thus reducing wages. Therefore, unemployment is used as an instrument of class struggle (Pollin, 1998). Thus, unemployment is a mechanism used by capitalists to avoid wage increase and retain their share of the profit (Pollin, 1998). Consequently Marxian theory argues that unemployment is functionally important in capitalism. Unemployment is a natural characteristic of capitalism and serves a class function in capitalism. The class functionality of unemployment arises from the fact

that capitalist use it to ensure that profits are not redistributed to workers; thus maintain the fundamental class structure (Pollin, 1998). Therefore, unemployment is related to the forces and the relations of production under capitalism. The forces result in unemployment through technical changes. Meanwhile the relations of production results in unemployment as an instrument of class struggle. Thus, unemployment is a permanent feature of capitalism, which results from technical displacement and class struggle, and it serves a class function. Conclusion Monetarists, neoclassical and Marxists share the same view that unemployment is a consequence of the power struggle for income distribution and political power even though they arrive at this through vastly different analyses and political views (Pollin, 1998). Furthermore, for Marxists unemployment is function to capitalism. However, Keynesians would reject the functionality of unemployment because they see it as irrational since there are unused resources in the economy (Pollin, 1998). Therefore, although the challenge of unemployment is centrally related to wages, each school offers a distinct understanding and analysis of unemployment based on its theoretical framework. Neoclassical and monetarists argue that unemployment is voluntary when workers reject equilibrium or involuntary due market imperfections caused by government and trade union interventions that result in real wages that exceed the equilibrium wage. Whilst Keynesians argue that unemployment is a consequence of well-functioning markets due to firms investing under uncertainty and business cycles; thus the economy does not automatically adjust itself toward full employment which necessitates government intervention to ensure this. Whereas Marxian economists argue that unemployment is a consequence of technical change and class struggle

between workers and capitalists; making unemployment functional for determining the power and income distribution between classes.

Bibliography Amendola, M., Gaffard, J.-L. & Saraceno, F., 2004. Wage Flexibility and Unemployment: The Keynesian Perspective Revisited. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 50(5), pp.65475. Forstater, M., 2000. Unemployment in Capitalist Economies: A History of Thought for Thinking About Policy. Working Paper No. 16. Center for Full Employment and Price Stability Working Paper Series. Friedman, M., 1968. The Role of Monetary Policy. American Economic Review, 58(1), pp.117. Hillier, B., 1991. Chapter 1. In The Macroeconomic Debate: Models of the Closed and Open Economy. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. pp.1-38. Leontief, W.W., 1936. The Fundamental Assumption of Mr. Keynes' Monetary Theory of Unemployment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 51(1), pp.192-97. Pollin, R., 1998. The Reserve Army of Labour and the Natural Rate of Unemployment: Can Marx, Kalecki, Friedman and Wall Street All be Wrong. Review of Radical Political Economics, 30(3), pp.1-13. Robinson, J., 1941. Marx on Unemployment. The Economic Journal, 51(202/203), pp.23448. Saad-Filho, A., 2002. Chapters 3-5. In The Value of Marx: Political Economy for Contemporary Capitalism. London and New York: Routledge. Stein, J.L., 1981. Monetarist, Keynesian, and New Classical Economics. The American Economic Review, 71(2), pp.139-44. Tobin, J., 1972. Inflation and Unemployment. Cowles Foundation Paper 361. Cowles Foundation. Wolff, R.D. & Resnick, S.A., 1988. Chapters 3. In Economics: Marxian vs Neoclassical. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. pp.125-238. Wray, L.R., 2011. Waiting for the Next Crash: The Minskyan Lessons We Failed to Learn. Public Policy Brief No. 120. Washington DC: Levy Economics Institute Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

* Siyaduma Biniza is currently a B.Com. (Hon) in Development Theory and Policy student at the University of the Witwatersrand, holding a B.Soc.Sci in Politics, Philosophy and Economics from the University of Cape Town.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Policies For South Africa's Industrialisation by Siya BinizaDocument16 paginiPolicies For South Africa's Industrialisation by Siya BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Mind The Gap: Inequality and A Minimum Wage in South AfricaDocument44 paginiMind The Gap: Inequality and A Minimum Wage in South AfricaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Kaldorian-Ricardian Impasse by Siya BinizaDocument11 paginiThe Kaldorian-Ricardian Impasse by Siya BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Critical Appraisal of Market-Led Economic Approaches - Reality vs. Perception by Siya BinizaDocument10 paginiCritical Appraisal of Market-Led Economic Approaches - Reality vs. Perception by Siya BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- Trade Liberalisation and The Challenges For Late Industrialisers by Siya BinizaDocument13 paginiTrade Liberalisation and The Challenges For Late Industrialisers by Siya BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Qualities of A Developmental Elite by Siya BinizaDocument14 paginiQualities of A Developmental Elite by Siya BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theoretical Limitations of Consumer Policy - Practical Implications by Siya BinizaDocument8 paginiTheoretical Limitations of Consumer Policy - Practical Implications by Siya BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Industrialisation and Development - Necessary But Insufficient by Siya BinizaDocument12 paginiIndustrialisation and Development - Necessary But Insufficient by Siya BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Comparative Advantage and Factor Endowments - Implications For Poor Countries by Siya Biniza PDFDocument10 paginiComparative Advantage and Factor Endowments - Implications For Poor Countries by Siya Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Davies Et Al - Class Struggle and The Periodisation of The SA StateDocument27 paginiDavies Et Al - Class Struggle and The Periodisation of The SA StateSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- New Institutional Economics and The Information Theoretic Approach: (Re-) Introducing The "Non-Economics" in Neoclassical EconomicsDocument5 paginiNew Institutional Economics and The Information Theoretic Approach: (Re-) Introducing The "Non-Economics" in Neoclassical EconomicsSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Critical Appraisal of The Theoretical Underpinnings of Privatisation - Evidence From The Electricity Sector in South Africa by Siya Biniza PDFDocument5 paginiA Critical Appraisal of The Theoretical Underpinnings of Privatisation - Evidence From The Electricity Sector in South Africa by Siya Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- A Comparative Analysis of Neoclassical Consumer and Producer Theory by Siya Biniza PDFDocument6 paginiA Comparative Analysis of Neoclassical Consumer and Producer Theory by Siya Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Relations Between Finance and The Real Economy: The South African CaseDocument12 paginiRelations Between Finance and The Real Economy: The South African CaseSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- A Critical Appraisal of New Institutional Economics by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument12 paginiA Critical Appraisal of New Institutional Economics by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya Biniza100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Impact of FDI On Unemployment in Post-Apartheid South Africa by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument39 paginiImpact of FDI On Unemployment in Post-Apartheid South Africa by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Explaining and Critically Analysing Minsky's ELR Solution To Full Employment by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument10 paginiExplaining and Critically Analysing Minsky's ELR Solution To Full Employment by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- Risks of Capital Liberalisation in Developing Economies by Siya Biniza PDFDocument8 paginiRisks of Capital Liberalisation in Developing Economies by Siya Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mauritius Trade Report by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument45 paginiMauritius Trade Report by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blecker's Critique of Fundamentals-Based International Financial Models by Siya Biniza PDFDocument10 paginiBlecker's Critique of Fundamentals-Based International Financial Models by Siya Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challenging The Contemporary Role of Central Banks by Siya Biniza PDFDocument8 paginiChallenging The Contemporary Role of Central Banks by Siya Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Siya Biniza - CVDocument4 paginiSiya Biniza - CVSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Possible Effects and Analysis of The NGP by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument9 paginiPossible Effects and Analysis of The NGP by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Review of Mark Gainsborough's 'Neglected State Bias in The Developmental State Theory' by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument11 paginiReview of Mark Gainsborough's 'Neglected State Bias in The Developmental State Theory' by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- African Agriculture and Its Relation To Development by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument14 paginiAfrican Agriculture and Its Relation To Development by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ikhaya Newsletter PDFDocument6 paginiIkhaya Newsletter PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Status Quo Elevator Pitch by Siyaduma BinizaDocument6 paginiThe Status Quo Elevator Pitch by Siyaduma BinizaSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challenges of Feeding A Hungry Planet by Siyaduma Biniza PDFDocument10 paginiChallenges of Feeding A Hungry Planet by Siyaduma Biniza PDFSiya BinizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Balance of PaymentDocument15 paginiBalance of PaymentShanaya GiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 8 Myfinancelab Solutions Pearsoncmgcom PDFDocument89 paginiChapter 8 Myfinancelab Solutions Pearsoncmgcom PDFChristopher Carpenter100% (7)

- (Module10) PUBLIC FISCAL ADMINISTRATIONDocument9 pagini(Module10) PUBLIC FISCAL ADMINISTRATIONJam Francisco100% (2)

- Tutorial 4 Solution PDFDocument5 paginiTutorial 4 Solution PDFRoite BeteroÎncă nu există evaluări

- B. Inggris 2 Uas. Genap 2022Document4 paginiB. Inggris 2 Uas. Genap 2022Tifa latifahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macroeconomy - FMCG Update Q4 17 (JHHP) PDFDocument46 paginiMacroeconomy - FMCG Update Q4 17 (JHHP) PDFBerry PakpahanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Some Basic Concepts of MacroeconomicsDocument16 paginiSome Basic Concepts of MacroeconomicsAnvi RaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tyagi Public School ABUS 2019-20 Class-Xii: English UNIT-1Document13 paginiTyagi Public School ABUS 2019-20 Class-Xii: English UNIT-1Mehul JindalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Circular Flow of IncomeDocument2 paginiCircular Flow of IncomeSyedaryanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engineering EconomicsDocument60 paginiEngineering EconomicsAbhineet GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dovish Vs HawkishDocument9 paginiDovish Vs Hawkisharti guptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHAPTER 3pdf - 211118 - 130431Document21 paginiCHAPTER 3pdf - 211118 - 130431Amalin IlyanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Chapter 4 The Interntional Flow of Funds and Exchange RatesDocument14 paginiChapter 4 The Interntional Flow of Funds and Exchange RatesRAY NICOLE MALINGI100% (1)

- Sir Syed Institute of Sciences and CommerceDocument3 paginiSir Syed Institute of Sciences and CommerceMian Hidayat ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter Two: Choice, Opportunity Costs and SpecializationDocument23 paginiChapter Two: Choice, Opportunity Costs and SpecializationPrachi Dua MalhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Solow Model Unleashed-XLS-EnGDocument13 paginiThe Solow Model Unleashed-XLS-EnGSumeet MadwaikarÎncă nu există evaluări

- AP Exam Past Exam PaperDocument3 paginiAP Exam Past Exam PaperAnnaLuxeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2.1 How Can Inflation Be Good For You - BBC NewsDocument1 pagină2.1 How Can Inflation Be Good For You - BBC NewsAbhinav UppalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Input-output analysis calculates income and employment multipliersDocument5 paginiInput-output analysis calculates income and employment multipliersafguzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paul KrugmanDocument1 paginăPaul KrugmandiariodocomercioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extra Session Midterm 2023Document13 paginiExtra Session Midterm 2023Yasmine MkÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0hsie F PDFDocument416 pagini0hsie F PDFchemkumar16Încă nu există evaluări

- Factors Affecting Delay in Real Estate PDocument15 paginiFactors Affecting Delay in Real Estate PAnonymous syzgQXwÎncă nu există evaluări

- HSC Economics Essay QuestionsDocument5 paginiHSC Economics Essay QuestionsYatharth100% (1)

- Copy of IUGC List of ThesessvfsdffsdDocument59 paginiCopy of IUGC List of ThesessvfsdffsdAsad HamidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pros Cons: CapitalismDocument5 paginiPros Cons: CapitalismAlejandro Sanchez ArequipaÎncă nu există evaluări

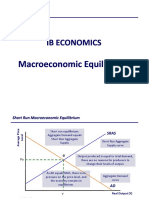

- IB MACRO EQUILIBRIUMDocument13 paginiIB MACRO EQUILIBRIUMPablo Torrecilla100% (1)

- MS-45 Int'l Fin Mgmt IMF Funding FacilitiesDocument8 paginiMS-45 Int'l Fin Mgmt IMF Funding FacilitiesGirija Khanna ChavliÎncă nu există evaluări

- TEST-3 Topic-Government Budget MM-25 Date-26/05/2020Document2 paginiTEST-3 Topic-Government Budget MM-25 Date-26/05/2020harrycreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Measures To Control InflationDocument6 paginiMeasures To Control InflationFeroz PashaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Trillion-Dollar Conspiracy: How the New World Order, Man-Made Diseases, and Zombie Banks Are Destroying AmericaDe la EverandThe Trillion-Dollar Conspiracy: How the New World Order, Man-Made Diseases, and Zombie Banks Are Destroying AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the WorldDe la EverandKleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the WorldEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (25)

- The Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumDe la EverandThe Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (12)