Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Irish Peace Process - Speech by Senator Jim Walsh

Încărcat de

FFRenewalDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Irish Peace Process - Speech by Senator Jim Walsh

Încărcat de

FFRenewalDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

33rd Annual Forum of the Parliamentarians for Global Action (PGA) In Colombo, Sri Lanka, Saturday October 29th

2011 Security Dimension Panel The Irish Peace Process by Senator Jim Walsh

Following the War of Independence by the IRA, 1916-1921, twenty six of Irelands thirty two counties secured independence from the British Empire under a treaty signed in 1922. This treaty also gave rise to a civil war between those in the Republican movement who agreed to accept the treaty and those who opposed it. The Independent State had in excess of 95% of their population as Catholic while in Northern Ireland it was 60% Protestant/Unionist and 40% Catholic/Nationalist.

There was very little interaction between both parts of Ireland over the following forty years during difficult economic times and the Second World War.

However, during the 1960s, the iconic era of modern pop music and flower children, greater global communications through the medium of television, and the greater manifestation of civil rights campaigns across many countries had its own effect on Northern Ireland. Inspired by this new sense of freedom, in pursuit of Human Rights, the Nationalist population of Northern Ireland took to the streets in a campaign to highlight the discrimination they were suffering under Unionist dominated rule. This discrimination would have been obvious in the area of housing allocations, employment opportunities and even in the right to vote. Eventually these street protests led to rioting, as the Unionist controlled police force overreacted in their efforts to prevent the civil rights marches taking place. This led to violence and the first killings of the conflict took place.

In the previous decades the IRA were relatively inactive with only sporadic incidences. However, the focus on the civil rights campaign, and the manner in which people were treated by the security forces mobilised the IRA into activity initially to protect those involved in the civil rights marches. This inevitably led to paramilitary conflict involving both the IRA and Loyalist paramilitary organisations. Arising from the violence internment without trial was introduced in August 1971 a highly controversial measure.

During this period the British Army had taken control of security in Northern Ireland and at a civil rights march in Derry on the 30th of January 1972 they shot twenty seven unarmed civilians, of whom fourteen were killed. This obviously led to a huge international out-cry, the burning of the British Embassy in Dublin, and created tremendous hostility within Nationalist Ireland. Bloody Sunday was a significant event in attracting young recruits to join the ranks of the IRA. The subsequent attempt to try to label the civilians that were shot as members of the IRA only antagonised and exacerbated the reaction. Interestingly it was only last year that it was acknowledged that none of those that were killed had arms or were involved in the conflict with the British forces on Bloody Sunday. A profuse apology from the British Prime Minister David Cameron was very well received by the citizens of Derry, thirty eight years after the killings.

The violence and the death toll continued through the 1970s including, inter alia, the Dublin and Monaghan bombings carried out by Loyalist paramilitaries involving collusion of the British Forces, where thirty four people were killed; the Warrenpoint ambush where eighteen British Army Soldiers were killed by an IRA bomb. A seminal event occurred in the summer of 1981 when IRA prisoners, campaigning for political status, went on hunger strike and ten prisoners died. The first to die was Bobby Sands and it had a significant impact on public opinion. In fact in the general election in the Republic in 1981 a number of the prisoners on hunger strike were elected to Parliament. They subsequently died. Throughout this period the conflict was being dealt with as a security issue but gradually it began to dawn on people that

it required a political intervention and solution. This realisation led in 1985 to the emergence of a British Irish axis which gave rise to the Anglo Irish Agreement of that year. This gave the Irish Government an institutional and consultative role in the governing of Northern Ireland for the first time. It was fiercely resisted by all shades of Unionism to no avail. The paramilitaries on both sides were not involved in this initiative and the violence continued including the Remembrance Day IRA bombing in Enniskillen in November 1987 which killed eleven civilians and one policeman with many others injured. There was wide spread revulsion and retaliatory sectarian killings by the Loyalist paramilitary groups.

However political dialogue was continuing between the British and Irish Governments and the axis was further strengthened by the Downing Street Declaration of 1993 and a Framework Document in 1995, which provided a vision on which the Good Friday Agreement could be negotiated. The multi-party talks, leading up to this agreement, were unprecedented in that they brought together for the first time all Northern Irish political parties, including those linked to paramilitary groups like Sinn Fein, the PUP and the UDP. The Good Friday Agreement was signed in April of 1998. It set out to redefine three sets of relations central to the thirty year conflict.

Strand One dealt with relations between the Northern Irish parties, strand two dealt with North/South relations and stand three dealt with East/West, or British/Irish relationships. Fundamental to the agreement was a compromise on the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, where the British Government conceded that they had no strategic or selfish interest in remaining there, and, would be guided by the principal of consent. This confirmed that the status quo would remain unless a majority of the population decided otherwise and they undertook to facilitate any such decision in the future. The Irish Government amended their Constitution to remove a territorial claim over Northern Ireland.

The agreement also provided constitutional guarantees for dual nationality, for the establishment of power sharing institutions now and into the future, and for overarching and interdependent British/Irish and North/South institutions. A great strength of the Good Friday agreement was that it was put to plebiscite and passed in Northern Ireland by 71% voting in favour, and in the Republic of Ireland with 90% voting in favour of it.

Despite this public endorsement the implementation of the agreement was slow and tedious with many disagreements arising, mostly from issues that could impact on party electoral support, leading to the suspension of the institutions and the power sharing Executive in Northern Ireland. The lengthiest being from 2002 to 2007. During that period a shift in political support in Northern Ireland led to the more hard line Democratic Unionist Party over-taking the Ulster Unionist Party, which had governed Northern Ireland since partition. On the Nationalist side the political arm of the IRA, Sinn Fein, replaced the SDLP as the major party representing the Nationalist population. This gave rise to increased tensions but patience and persistence from both the Irish and British Governments led to the reinstatement of the institutions and the establishment of a power sharing Executive on the 8th of May 2007. The institutions have been up and running since then.

Strand One: Strand One of the agreement provided for the replacement of direct rule from London with an elected power sharing Assembly, with extensive devolved Executive powers. First and Deputy First Ministers would be elected from the Assembly to serve as joint interdependent presidents of the Executive and the agreement almost ensures that a Unionist and a Nationalist will share these top two posts. Ministers are appointed to the Executive on the basis of the dHondt formula which ensures that representation of all major parties is included on the Executive.

Strand Two:

Strand two establishes a North/South Ministerial Council where Ministers from the Irish Government and the Assembly Executive would meet to cooperate, consult and develop policy on areas of mutual interest, including implementation on an all island and cross border basis.

In each of the six areas of cooperation, namely agriculture, environment, education, health, tourism and transport, common policies and approaches are agreed in the North/South Ministerial Council but implemented separately in each jurisdiction. However a greater all island focus is materialising, for example Tourism Ireland which markets the island, North and South.

There are also North/South implementation bodies which operate on an all island basis. All operate under the overall policy direction of the North/South Ministerial Council; these include Waterways Ireland, Food Safety Promotion Board, Trade and Business Development Body, Special European Programme Body, a Language Body to promote the Irish language and Ulster Scots, Foyle Carlingford and Irish Lights Commission.

Strand Three: Strand three provided for the establishment of a consultative and consensus building British Irish Council for representatives of the devolved assemblies of the United Kingdom, the British Government and Irish Government.

The British Irish Intergovernmental Conference brings together the British and Irish Governments to promote bilateral cooperation at all levels on all matters of mutual interest within the competence of both governments. The Conference also involves Northern Ireland Ministers and generally meets at the level of Foreign Affairs Ministers, but provision is also made for Summit Meetings. The Intergovernmental Conference was hugely significant in the process of implementing the Good Friday and St. Andrews Agreements.

Agreement on Confidence Building Measures Critical to the viability of the Good Friday Agreement was agreement on other issues that were central to the conflict. They were frequently referred to as confidence building measures. These measures were A) Decommissioning The responsibility for achieving the decommissioning of paramilitary arms and effective demobilisation of paramilitary organisations was given to an Independent International Commission on Decommissioning, whose job was to monitor, review and verify progress on the decommissioning. This took considerably longer than expected and in fact was a significant factor leading to the suspension of the institutions for periods.

B) Demilitarisation and Normalisation of the Security Situation. The agreement committed the British Government to begin a series of phased developments to demilitarise Northern Ireland, including the removal of security operations, the reduction of ground forces to levels compatible with a peaceful society and the removal of emergency powers.

C) Police Reform The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) were seen as predominately Unionist, and, a new beginning was sought in aspiring to a police service capable of attracting and sustaining support from the community as a whole. The Patten Commission was established which made recommendations on the procedures and reforms necessary to transform the existing police force agreed to by the parties to the agreement. This led to a quota system to ensure that the predominately Protestant police force would recruit Catholic police officers to achieve this objective.

D) Criminal Justice

An Independent Commission was established to review the criminal justice system and make recommendations for its reform. It was also agreed that the justice function would be devolved to the Northern Ireland Executive. This took until March 2010, when the parties found a way to implement the policy by agreeing to compromise that the Justice Minister would be elected by a cross community vote within the Assembly. E) Prisoners A key component in achieving support from the paramilitaries was that both the British and Irish Governments committed to introduce mechanisms of the roll out of early releases of the prisoners who were affiliated to the organisations judged to be on unequivocal cease-fire.

F) Civil Rights, Safe Guards and Equality of Opportunity The British Government committed to incorporate the European Convention on Human Rights into Northern Ireland law. In addition a statutory Human Rights Commission and Equality Commissions were established to monitor the institutions of the Good Friday Agreement.

Conclusion: A lot of progress has ensued since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Most recently a new election to the Assembly reinstated the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Fein as the leading political parties, with the new Executive under first Minister Peter Robinson and Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness, re-elected and working well.

Importantly, partnership and personal relationships are also significantly improving, which provides a stable foundation for the peace process and for the Province into the future.

In this regard I feel it is worthy of note to mention that the personal chemistry that existed between Prime Minister Tony Blair and Taoiseach Bertie Ahern was fundamental to reaching

agreement in the first instance in 1998 under the expert chairmanship of Senator George Mitchell from the United States. More importantly, in the following decade, when various serious obstacles emerged, their determination, perseverance and excellent working relationship was crucial in their gaining the trust and confidence of all participants and reaching the point we have now achieved.

This of course has been internationally recognised, in that at this time they are both engaged in meeting with ETA and the authorities in the Basque Country with a view to achieving a similar outcome in that region.

The experience in Northern Ireland provides a template for conflict resolution in other areas around the world. It illustrates clearly that these conflicts may not be settled by security measures alone. Parliamentarians do and can make a difference when people recognise that the underlying causes of conflict must be comprehensively settled in order to ensure a sustainable lasting peace to which we all aspire.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Moore Street Area Renewal and Development Bill 2015Document20 paginiMoore Street Area Renewal and Development Bill 2015FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fiscal Responsibility (Amendment) Bill 2015Document5 paginiFiscal Responsibility (Amendment) Bill 2015FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fianna Fáil Policy Paper: Michael Moynihan TDDocument10 paginiFianna Fáil Policy Paper: Michael Moynihan TDFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Bank and Financial Services Authority of Ireland Bill 2013Document2 paginiCentral Bank and Financial Services Authority of Ireland Bill 2013FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fianna Fáil Foreign Affairs Policy PaperDocument20 paginiFianna Fáil Foreign Affairs Policy PaperFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assaults On Elderly Persons Bill 2015Document8 paginiAssaults On Elderly Persons Bill 2015FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Low Pay Commission SubmissionDocument8 paginiLow Pay Commission SubmissionFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clar 2015 - An Ireland For AllDocument80 paginiClar 2015 - An Ireland For AllFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Policy V7Document49 paginiHealth Policy V7FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- FF National Drugs Action PlanDocument16 paginiFF National Drugs Action PlanFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Streets Ahead Policy PaperDocument32 paginiStreets Ahead Policy PaperFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Migrant Earned Regularisation Bill 2015Document16 paginiMigrant Earned Regularisation Bill 2015FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Bank Letter Re Mortgage Arrears StatsDocument3 paginiCentral Bank Letter Re Mortgage Arrears StatsFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Family Home Mortgage Settlement Arrangement Bill 2014Document13 paginiThe Family Home Mortgage Settlement Arrangement Bill 2014FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Markiewicz ReportDocument28 paginiMarkiewicz ReportFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appraisal Report 19112014 FinalDocument111 paginiAppraisal Report 19112014 FinalFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mario Draghi Letter To Michael McGrathDocument2 paginiMario Draghi Letter To Michael McGrathFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Freedom of Information MaterialDocument2 paginiFreedom of Information MaterialFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fianna Fáil Submission To The Central Bank On Mortgage Lending RulesDocument1 paginăFianna Fáil Submission To The Central Bank On Mortgage Lending RulesFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- State Boards Appointments Bill 2014Document12 paginiState Boards Appointments Bill 2014FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Services (Exempt Charges) Bill 2014Document2 paginiWater Services (Exempt Charges) Bill 2014FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

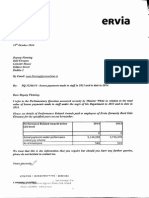

- Ervia BonusesDocument1 paginăErvia BonusesFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Refundable Tax Credits Discussion PaperDocument4 paginiRefundable Tax Credits Discussion PaperFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fianna Fail Pre Budget Submission Final DraftDocument40 paginiFianna Fail Pre Budget Submission Final DraftFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Submission by Michael McGrath TD On Behalf of Fianna FáilDocument4 paginiSubmission by Michael McGrath TD On Behalf of Fianna FáilFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning and Development (Amendment) Bill 2014Document2 paginiPlanning and Development (Amendment) Bill 2014FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ógra Fianna Fáil Pre-Budget Submission 2015Document22 paginiÓgra Fianna Fáil Pre-Budget Submission 2015OgraFiannaFailÎncă nu există evaluări

- IMF Letter To Michael McGrath TDDocument2 paginiIMF Letter To Michael McGrath TDFFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Local Government Bill 2014Document20 paginiLocal Government Bill 2014FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Services (Exempt Charges) Bill 2014Document2 paginiWater Services (Exempt Charges) Bill 2014FFRenewalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- MX - Inside The Uda Volunteers and ViolenceDocument242 paginiMX - Inside The Uda Volunteers and ViolencePedro Navarro SeguraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steve Bruce Paisley Religion and Politics in Nobookzz OrgDocument310 paginiSteve Bruce Paisley Religion and Politics in Nobookzz Orgapi-270964392100% (1)

- (Routledge International Studies of Women and Place) Rosemary Sales - Women Divided - Gender, Religion and Politics in Northern Ireland (1997, Routledge)Document253 pagini(Routledge International Studies of Women and Place) Rosemary Sales - Women Divided - Gender, Religion and Politics in Northern Ireland (1997, Routledge)fiyitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Studies NotesDocument24 paginiSocial Studies NotesVernon100% (1)

- Newsletter - Spring 2012Document14 paginiNewsletter - Spring 2012אמיר סטרנסÎncă nu există evaluări

- DMir 1912 04 10 001-UlsterDocument16 paginiDMir 1912 04 10 001-UlsterTitanicwareÎncă nu există evaluări

- FinancialTimes May.22.2023Document26 paginiFinancialTimes May.22.2023namza61Încă nu există evaluări

- Topic 51 - Oscar Wilde and Bernard ShawDocument21 paginiTopic 51 - Oscar Wilde and Bernard Shawvioleta2ruanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crenshaw On IntersectionalityDocument29 paginiCrenshaw On IntersectionalityBlythe Tom100% (2)

- Ballymurphy and The Irish War (PDFDrive)Document436 paginiBallymurphy and The Irish War (PDFDrive)muhammad raflyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 56 Historical Relations Between Ireland and Great Britain. Irish Authors: Sean O'Casey and James JoyceDocument31 paginiUnit 56 Historical Relations Between Ireland and Great Britain. Irish Authors: Sean O'Casey and James JoyceAngel MaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- +english - Oral Matura Jachs - All TopicsDocument37 pagini+english - Oral Matura Jachs - All Topicsapi-3754905100% (1)

- Understanding The Northern Ireland Conflict - David HollowayDocument28 paginiUnderstanding The Northern Ireland Conflict - David HollowayFrancisco GarcíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BelfastDocument64 paginiBelfastbplacesÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Make Homemade ExplosivesDocument25 paginiHow To Make Homemade Explosivesk3t4nÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dissertation Questions On Northern IrelandDocument7 paginiDissertation Questions On Northern IrelandFindSomeoneToWriteMyCollegePaperSingapore100% (1)

- A Two Party System in UKDocument4 paginiA Two Party System in UKdjetelina18Încă nu există evaluări

- Making Sense of The TroublesDocument376 paginiMaking Sense of The TroublesJonah DeBeir100% (5)

- The Troubles Magazine Issue 01Document72 paginiThe Troubles Magazine Issue 01Mauricio Leme100% (1)

- T56 PDFDocument36 paginiT56 PDFÁlvaro Sánchez AbadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tony Blair Hero or VillainDocument7 paginiTony Blair Hero or VillainMr. KenzÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRC NI Peace Monitoring Report 2013Document186 paginiCRC NI Peace Monitoring Report 2013Allan LEONARDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Front Nov 5Document1 paginăFront Nov 5rebecca_black2Încă nu există evaluări

- The Heath Government, 1970-74Document3 paginiThe Heath Government, 1970-74Andreea Liliana100% (1)

- Unionists, Loyalists, and Conflict Transformation in Northern IrelandDocument277 paginiUnionists, Loyalists, and Conflict Transformation in Northern Irelandtm_drummerÎncă nu există evaluări

- CE - The Guardian View On The 2019 Election ResultDocument3 paginiCE - The Guardian View On The 2019 Election ResultYanisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bryan, Dominic - Orange ParadesDocument222 paginiBryan, Dominic - Orange ParadesdirlidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Redefining Unionism: The Role of The Diaspora?Document20 paginiRedefining Unionism: The Role of The Diaspora?The International Journal of Conflict & ReconciliationÎncă nu există evaluări