Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

SSD Cards

Încărcat de

toobleroonDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

SSD Cards

Încărcat de

toobleroonDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

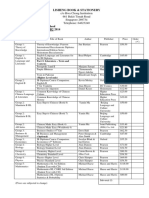

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

** 2NC SSD

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

Decision making skills are necessary to solve existential threatsnow is uniquely key because of increasing complexity and lack of information literacy Lundberg 10 (Lundberg, Christian O., professor of communications at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, The Allred Initiative and Debate Across the Curriculum: Reinventing the Tradition of Debate at North Carolina, Navigating Opportunity: Policy Debate in the 21st Century)FS

The second major problem with the critique that identifies a naivety in articulating debate and democracy is that it presumes that the primary pedagogical outcome of debate is speech capacities. But the democratic capacities built by debate are not limited to speech as indicated earlier,

--terminal impact

debate builds capacity for critical thinking, analysis of public claims, informed decision making, and better public judgment. If the picture of modern political life that underwrites this critique of debate is a pessimistic view of increasingly labyrinthine and bureaucratic administrative politics, rapid scientific and technological change outpacing the capacities of the citizenry to comprehend them, and ever-expanding insular special-interest- and money-driven politics, it is a puzzling solution, at best, to argue that these conditions warrant giving up on debate. If democracy is open to rearticulation, it is open to rearticulation precisely because as the challenges of modern political life proliferate, the citizenrys capacities can change, which is one of the primary reasons that theorists of democracy such as Dewey in The Public and Its Problems place such a high premium on education (Dewey 1988, 63, 154). Debate provides an indispensible form of education in the modern articulation of democracy because it builds precisely the skills that allow the citizenry to research and be informed about policy decisions that impact them, to sort through and evaluate the evidence for and relative merits of arguments for and against a policy in an increasingly information-rich environment, and to prioritize their time and political energies toward policies that matter the most to them. The merits of debate as a tool for building democratic capacity-building take on a special significance in the context of information literacy. John Larkin (2005, 140) argues that one of the primary failings of modern colleges and universities is that they have not changed curriculum to match with the challenges of a new information environment. This is a problem for the course of academic study in our current context, but perhaps more important, argues Larkin, for the future of a citizenry that will need to make evaluative choices against an increasingly complex and multimediated information environment (ibid.). Larkins study tested the benefits of debate participation on information-literacy skills and concluded that in-class debate participants reported significantly higher self-efficacy ratings of their ability to navigate academic search databases and to effectively search and use other Web resources: To analyze the self-report ratings of the instructional and control group students, we first conducted a

multivariate analysis of variance on all of the ratings, looking jointly at the effect of instruction/no instruction and debate topic . . . that it did not matter which topic students had been assigned . . . students in the Instructional [debate] group were significantly more confident in their ability to access information and less likely to feel that they needed help to do so. . . . These findings clearly indicate greater self-efficacy for online

searching among students who participated in [debate]. . . . These results constitute strong support for the effectiveness of the project on

students self-efficacy for online searching in the academic databases. There was an unintended effect, however: After doing . . . the project, instructional group students also felt more confident than the other students in their ability to get good information from Yahoo and Google. It may be that the library research experience increased self-efficacy for any searching, not just in academic databases. (Larkin 2005, 144) Larkins study substantiates Thomas Worthen and Gaylen Packs (1992, 3) claim that debate in the college classroom plays a critical role in fostering the kind of problem-

solving skills demanded by the increasingly rich media and information environment of modernity. Though their essay was written in 1992 on the cusp of the eventual explosion of the Internet as a medium, Worthen and Packs framing of the issue was prescient: the primary question facing todays student has changed from how to best research a topic to the crucial question of learning how to best evaluate which arguments to cite and rely upon from an easily accessible and veritable cornucopia of materials. There are, without a doubt, a number of important criticisms of employing debate as a model for democratic deliberation. But cumulatively, the evidence presented here warrants strong support for expanding debate practice in the classroom as a technology for enhancing democratic deliberative capacities. The unique combination of criticalthinking skills, research and information-processing skills, oral-communication skills, and capacities for listening and thoughtful, open engagement with hotly contested issues argues for debate as a crucial component of a rich and vital democratic life. In-class debate practice both aids students in achieving the best goals of college and university education and serves as an unmatched practice for creating thoughtful, engaged, open-minded, and self-critical students who are open to the possibilities of meaningful political engagement and new articulations of democratic life. Expanding this practice is crucial, if only because the more we produce citizens who can actively and effectively engage the political process, the more likely we are to produce revisions of democratic life that are necessary if democracy is not only to survive, but to thrive and to deal with systemic threats that risk our collective extinction . Democratic societies face a myriad of challenges, including: domestic and international issues of class, gender, and racial justice; wholesale environmental destruction and the potential for rapid climate change; emerging threats to international stability in the form of terrorism, intervention, and new possibilities for great power conflict; and increasing challenges of rapid globalization, including an increasingly volatile global economic structure. More than any specific policy or proposal, an informed and active citizenry that deliberates with greater skill and sensitivity provides one of the best hopes for responsive and effective democratic governance, and by extension, one of the last best hopes for dealing with the existential challenges to

2

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

democracy in an increasingly complex world. Given the challenge of perfecting our collective political skill, and in drawing on the best of our collective creative intelligence, it is incumbent on us to both make the case for and, more important, to do the concrete work to realize an expanded commitment to debate at colleges and universities.

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

Real world decision-making skills outweigh any educational benefits Strait and Wallace 7

(Strait, L. Paul, George Mason University and Wallace, Brett, George Washington University, The Scope of Negative Fiat and the Logic of Decision Making, Policy Cures? Health Assistance to Africa, Debaters Research Guide)FS More to the point, debate certainly helps teach a lot of skills, yet we believe that t he way policy debate participation encourages you to

--decision making o/w edu.

think is the most valuable educational benefit, because how someone makes decisions determines how they will employ the rest of their abilities, including the research and communication skills that debate builds . Plenty of debate

theory articles have explained either the value of debate, or the way in which alternate actor strategies are detrimental to real-world education, but none so far have attempted to tie these concepts together. We will now explain how decision-making skill development is the foremost value

of policy debate and how this benefit is the decision-rule to resolving all theoretical discussions about negative fiat. Why debate? Some do it for

scholarships, some do it for social purposes, and many just believe it is fun. These are certainly all relevant considerations when making the decision to join the debate team, but as debate theorists they arent the focus of our concern. Our concern is finding a framework for debate that

educates the largest quantity of students with the highest quality of skills, while at the same time preserving competitive equity. The ability to make decisions deriving from discussions, argumentation or debate, is the key skill. It is the one thing every single one of us will do every day of our lives besides breathing. Decision-making transcends boundaries between categories of learning like policy education and kritik education, it makes irrelevant considerations of whether we will eventually be policymakers, and it transcends questions of what substantive content a debate round should contain. The implication for this analysis is that the critical thinking and argumentative skills offered by real-world decision-making are comparatively greater than any educational disadvantage weighed against them. It is the skills we learn, not the content of our arguments, that can best improve all of our lives. While policy comparison skills are going to be learned through debate in one way or another, those skills are useless if they are not grounded in the kind of logic actually used to make decisions. The academic studies and research supporting this position are numerous. Richard Fulkerson (1996) explains that argumentationis the chief cognitive activity by which a democracy, a field of study, a corporation, or a committee functions. . . And it is vitally important that high school and college students learn both to argue well and to critique the arguments of others (p. 16). Stuart Yeh (1998) comes to the conclusion that debate allows even cultural minority students to identify an issue, consider different views, form and defend a viewpoint, and consider and respond to counterargumentsThe ability to write effective arguments influences grades, academic success, and preparation for college and employme nt (p. 49).Certainly, these are all reasons why

debate and argumentation themselves are valuable, so why is real world decision-making critical to argumentative thinking? Although people might occasionally think about problems from the position of an ideal decisionmaker (c.f. Ulrich, 1981, quoted in Korcok, 2001), in debate we should be concerned with what type of argumentative thinking is the most relevant to real-world intelligence and the decisions that people make every day in their lives, not academic trivialities. It is precisely because it is rooted inreal-world logic that argumentative thinking has value. Deanna Kuhns research in Thinking as Argument explains this by stating that no other kind of thinking matters more-or contributes more to the quality and

fulfillment of peoples lives, both individually and collectively (p. 156).

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

Switch side debate is key to decision-making--- it solves cognitive dissonance, studies prove Butt 10 Ph.D. in Philosophy at Wayne State University. Attended George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, graduating with degrees in International

Studies and Communication in 1993. Neil completed his Masters Degree in Communication and Policy Analysis, also from GMU, in 2000. He has coached policy debate at the high school and college level since 1988, and has taught classes at the college level since 1993, including public speaking, interpersonal and small group communication, argumentation and debate, research methods, and rhetorical criticism. (Neil Stuart, Argument Construction, Argument Evaluation, And Decision-Making: A Content Analysis Of Argumentation And Debate Textbooks, (2010), Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 77. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/77) RaPa Chapter 1 identified cognitive dissonance and egocentric thinking as biases that create blind spots for even skilled

--solves decision making ext.

thinkers. Research has shown that people can be taught to overcome these natural tendencies, but the training must extend beyond just teaching the skills to providing a larger framework or process for applying those skills consistently. Introducing people to external procedures, encouraging self-awareness and the ability to look at their decisions as if it was someone else, and being trained to accept criticism can overcome these bad habits (Tavris & Aronson, 2007). Egocentric thinking can also be overcome by practicing considering issues from both sides (or multiple perspectives ), teaching

people to be aware of the criteria they are using, putting both sides into a larger perspective, and teaching people to apply the standards they have learned to themselves (Elder & Paul, 2004). Debate, especially switch-side debate, allows people to separate issue from self (Greene & Hicks, 2005), which

suggests that it is exactly the kind of training that helps people avoid the kind of dissonance that disrupts their judgment. Debate provides external procedures for evaluating decisions that provide participants with a more objective checklist than their own feelings. Debate provides incentives to get used to criticism because participants regularly receive and benefit from judge or instructor feedback, and the desire for success provides an incentive for critical and honest self-reflection. Switch side debate is key to decision-making skills Butt 10 Ph.D. in Philosophy at Wayne State University. Attended George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, graduating with degrees in International

Studies and Communication in 1993. Neil completed his Masters Degree in Communication and Policy Analysis, also from GMU, in 2000. He has coached policy debate at the high school and college level since 1988, and has taught classes at the college level since 1993, including public speaking, interpersonal and small group communication, argumentation and debate, research methods, and rhetorical criticism. (Neil Stuart, Argument Construction, Argument Evaluation, And Decision-Making: A Content Analysis Of Argumentation And Debate Textbooks, (2010), Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 77. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/77) RaPa In sum, approaches which include switch side debate are superior to approaches focusing exclusively on argument

theory, the major criticisms of that approach are unwarranted, and while the approach can be augmented, it should not be replaced by any of the currently proposed alternatives. While t he research suggests that full participation in competitive debate as an extracurricular or co-curricular activity will do more for students than can be achieved in the classroom, argumentation and debate courses which include elements of the competitive activity, especially student research, a switch-side format, and a substantial amount of practice, can still provide many benefits . Debate, whether in the classroom or as an extracurricular activity seems to be a good way to improve the critical thinking and decision-making skills

discussed in Chapter 1.

Switch side is key to decision makingit improves info processing, argument analysis, and encourages consensus building Mitchell 10 Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of Communication at the University of Pittsburgh, where he also

directs the William Pitt Debating Union. (Gordon R. Mitchell, Switch-Side Debating Meets Demand-Driven Rhetoric of Science, Rhetoric & Public Affairs Vol. 13, No. 1, 2010, pp. 95120. http://www.pitt.edu/~gordonm/JPubs/Mitchell2010.pdf) RaPa

Surmounting this complex epistemological dilemma requires more than sheer information processing power; it demands forms of communicative dexterity that enable translation of ideas across differences and facilitate cooperative work by interlocutors from heterogeneous backgrounds. How can such communicative dexterity be cultivated? Hart and Simon see structured argumentation as a promising tool in this regard. In their view, t he unique virtue of rigorous debates is that they support diverse points of view while encouraging consensus formation. This dual function of argumentation provides both intelligence producers and policy consumers with a view into the methodologies and associated evidence used to produce analytical product, effectively creating a common language that might help move knowledge across organizational barriers without loss of accuracy or relevance . 20 Hart and Simons insights, coupled with the previously mentioned institutional initiatives promoting switch-side debating in the intelligence community, carve out a new zone of relevance where argumentation theorys salience is pronounced and growing. Given the centrality of evidentiary analysis in this zone, it is useful to

revisit how argumentation scholars have theorized the functions of evidence in debating contexts.

Switch Side debate has been empirically proven to assist deliberation Sikkink 62 Donald E. Sikkink is chairman Department Of Speech, South Dakota Slate College, Brookings. (Donald E. Sikkink, Evidence on the both

sides debate controversy, The Speech Teacher Volume 11, Issue 1, 1962, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03634526209377194) RaPa

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

THE controversy over the merits of debating both sides leads to the conclusion that we have two problems.1 (1) We need research information to refute or support the assertions made in this controvers y. (2) We need a commonly

accepted definition as to the objectives and purposes of interschool debate. The following study was completed in the hope of making some limited progress in attacking the first of these problems. At the start of the 1959~6o school year, eight Directors of Debate' had their debaters indicate their

attitude on the national proposition by marking a live point scale. The five points on the scale were Strongly Agree, Agree, Undecided,

Disagree, and Strongly Disagree. The national proposition was Resolved: That Congress should be Given Power to Reverse Decision of the Supreme Court. At the end of the school year each director had the student complete a second form which again called for an expression of attitude on the proposition an which also asked for the side debate during that year. Eighty-one students completed both forms and the results are based on that sample. Table I gives the percentage of students marking each attitude category at the beginning and end of the debate season and also indicates average attitude. The averages were computed by assigning the following numerical values to points on the scale: Strongly Agree 5, Agree 4, Undecided 3, Disagree 2, Strongly Disagree 1. Table II indicates the specific nature of the individual attitude shifts that took place and the average shift for each category. The average shift was computed by counting each shift of one position on the scale as representing shift of one numerical point. For example a shift from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree would represent shift of 4 points. Table III provides a comparison of attitude shift for those students debating the affirmative with those who debated on the negative and those who debated both sides. So few of the students indicated they had debated only one side that the groups saying they had debated much more affirmative or negative were combined with those saying they had debated only affirmative or negative. The affirmative group consisted of seven students who had debated only affirmative and 10 students who had debated much more affirmative than negative. The negative group consisted of five students who had debated only negative and thirteen students who had debated much more negative than affirmative. Assuming the usual limitations imposed by sample size, representativeness, etc., we may tentatively make the following observations: First, we should note the

large number (46%) of the students who marked the Undecided category at the beginning of the year and the limited number of students (5% and 12%) who marked the extreme positions of Strongly Agree and Strongly Disagree. A scale of the type used in

this study does not provide any real measure of attitude intensity and, as a result, we can never be quite sure what depth of attitude is involved in any category. This may be especially true of those who marked Agree and Disagree where some of these students may have strong convictions and some only the slightest of belief. However, it is probably fair to conclude that for this sample someplace between 50% to 80% of the students did not have any strong convictions or beliefs on the proposition at the beginning of the season. Second, we should note the effect of debating on these initial attitude position s. By

the end of the season a sizeable shift has taken place with the average change being in the negative direction. The Undecided category is reduced by 32% and the Disagree category is increased by 31%. It appears that debating this proposition helped the students in this sample to make up their minds . While the overall shift was negative there was some

individual shifting to the affirmative, especially by individuals who had marked extreme negative positions at the beginning of the year. We probably had two factors operating with this topic: (1) An overall tendency to shift to the negative side of the topic; and (2) A tendency to modify extreme negative positions taken at the beginning of the season. Third, it is apparent that the shift for those who debated on the negative and those who debated both sides is approximately equal. This might be expected since the overall tendency on this question was to shift in the negative direction, This result makes even more interesting what happened to those students who debated on the affirmative. We find in studying the affirmative group on percentage of affirmative shift, percentage of negative shift, and average shift, that the results appear to deviate considerably from those students who debated both sides. Contrary to the small percentage (5%) of both sides debaters shifting to a stronger affirmative position, 35% of the affirmative group shifted to a stronger affirmative position. While 58% of the both sides debaters shifted to a stronger negative position, 47% of the affirmative debaters made this shift. This is even more apparent in studying the average shift where the both sides group shifts a --.77 as compared to a -.12 for the affirmative group. We probably may conclude that the result of debating affirmative on this topic, which appears to be "negatively loaded," is strongly to reduce the tendency to shift in the negative direction and to increase the possibility of holding to ones initial attitude preference. Let us now try to apply this study to two of the issues in the both sides controversy:

Murphy argues that it is unnecessary to debate both sides in order to understand fully both since "The Debater can brief the other side. He can explore the other side and read about it. In actual debate, one can listen to the other side if he will but open his ears and his mind. The data presented here on the attitude shift for the affirmative group do not support Mr. Murphy's position. These affirmative debaters undoubtedly explored the other side, some of them probably briefed it, and they all debated; yet their shift in attitude appears to be quite different from those who verbalized both sides of the proposition. It may be that one has to take the other side verbally in order to appreciate its actual strength. A second issue is the belief that many debaters at the beginning of a season do not know enough about the topic to

take a stand. This study supports that belief, for at least 46% of the students were undecided at the beginning of the season. If we would make the assumption that only the positions of Strongly Agree and Strongly Disagree represent real conviction, then we could assert that 83% of this student group did not initially take an intensive stand on this topic. If such figures represent fact, then it is possible that we may have magnified the both sides controversy far out of proportion since it may apply to so few students. While we must be fully aware of the assumptions and limitations that need to be imposed on the type of data collected, this information hints at conclusions that should be measured constantly. It hints that most of our debaters may not have strong

convictions on the topics we debate and thus the both sides issue is a minor one. If a small group of students do have absolute convictions, this may be a coaching problem where the director provides a one-sided experience for this student. The results also hint that these students may under such a system never learn to grasp fully the importance of the opposition point of view. Here a new controversy may be started with the assertion that a coach may have an "ethical

responsibility to force his students to debate both sides in order that the full impact of the debate experience be achieved. I will wait to make this 180 degree turn in the direction of the original argument when more evidence is presented either supporting or destroying the speculations which have been presented.

The skills of switch side debate make us better decision-makers Muir 93 Communication studies at George Mason University (Star A., A Defense of the Ethics of Contemporary Debate, Philosophy & Rhetoric, Vol.

26, No. 4 (1993), pp. 277-295, ttp://www.jstor.org/stable/40237780) RaPa

The isolation of debate from the real world is a much more potent challenge to the activity. There are indeed "esoteric"

techniques, special terminologies, and procedural constraints that limit the applicability of debate knowledge and skills to the rest of the student's life. The first and most obvious rejoinder is that debate puts students into greater contact with the real world by forcing them to read

a great deal of information from popular periodicals, scholarly books and Journals, government documents, reports, newsletters, and daily newspapers. Debaters also frequently seek out and query administrators, policy makers, and

6

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

public personae to gain more data. The constant consumption of material by, from, and about the real world is significantly constitutive: The information grounds the issues under discussion, and the process shapes the relationship of the citizen to the public arena. Debaters can become more involved than uninformed Citizens because they know about important issues, and because they know how to find out more information about these issues. Switch-side debating is not peripheral to this value. A thorough research effort is guided in large part by the knowledge that both sides of the issues must be covered. Where a particular controversy might involve affirmative

research among conservative sources, the negative must research the liberal perspective. Where scientific studies predominate in justifying a particular policy, research in cultural studies may be necessary to counter the adoption of the policy. Debating a ban on the teaching of creationism in public schools, for example, forces research on the scientific consensus on evolution, the viability of theological grounds for public policy, and a consideration of the nature of science itself . A primary value of switch-side debate, that of encouraging research skills, is fundamentally an attachment to the "real world," and is enhanced by requiring debaters to investigate both sides of an issue. A second response to the charge of segmentation is the proclivity of

debaters to become involved in public policy and international affairs . Although the stereotype is that debaters become lawyers, students seeking other professional areas also see value in the skills of debate . Business management, government, politics, international relations, teaching, public policy, and so on, are ail significant career options for debaters. In surveys, ex-debaters frequently respond that debate was the single most educational activity of their college careers. Most classes provide information, but debate compels the use, assimilation, and evaluation of information that is not required in most classrooms . As one debate alumnus writes:

"The lessons learned and the experience gained have been more valuable to me than any other aspect of my formal education."31 It is no wonder, then, that surveys of Congress and other policy-making institutions reveal a high percentage of exdebaters. 32 The argument that debate isolates participants from the "real world" is not sustained in practice when debaters, trained in research, organization, strategy, and technique, are consistently effective in integrating these skills into success on the job. Even the specialized jargon required to play the game successfully has

benefits in terms of analyzing and understanding society's Problems. Consider the terminology of the "disadvantage" against the affirmative's plan: There

is a "link" between the plan and some effect, or "impact"; the link can be actions that push us over some "threshold" to an impact, or it can be a "linear" relationship where each increase causes an increase in the impact; the link from the affirmative plan to the impact must be "unique," in that the plan itself is largely responsible for the impact; the affirmative may argue a "turnaround" to the disadvantage, claiming it as an advantage for the plan. Such s pecialized

jargon may separate debate talk from other types of discourse, but the ideas represented here are also significant and useful for analyzing the relative desirability of public policies. There really are threshold and brink issues in evaluating public policies. Though listening to debaters talk is somewhat disconcerting for a lay person, familiarity with these concepts is an essential means of connecting the research they do with the evaluation of options confronting Citizens and decision makers in political and social contexts. This familiarity is directly related to the motivation and the ability to get involved in issues and controversies of public importance. A third point about isolation from the real world is that switchside debate develops habits of the mind and instills a lifelong pattern of critical assessment. Students who have debated both sides of a topic are better voters, Dell writes, because of "their habit of analyzing both sides before forming a conclusion ."33 O'Neill, Laycock and Scales, responding in part to

Roosevelt's indictment, iterated the basic position in 1931: Skill in the use of facts and inferences available may be gained on either side of a question without regard to convictions. Instruction and practice in debate should give young men this skill. And where these matters are properly handled, stress is not laid on getting the speaker to think rightly in regard to the merits of either side of these questions but to think accurately on both sides.34 Reasons for not

taking a position counter to one's beliefs (isolation from the "real world," sophistry) are largely outweighed by the benefit of such mental habits throughout an individual's life. The jargon, strategies, and techniques may be alienating to "outsiders," but they are also paradoxically integrative as well . Playing the game of debate involves certain skills, including research and policy evaluation, that evolve along with a debater's consciousness of the complexities of moral and political dilemmas. This conceptual development is a basis for the formation of ideas and relational thinking necessary for effective public decision making, making even the game of debate a significant benefit in solving real world problems. Switch side debate encourages better analysis and engages debaters Zainuddin and Moore 3

(Zainuddin, Hanizah, professor at Florida Atlantic University, and Moore, Rashid, professor at Nova Southeastern University, Enhancing Critical Thinking with Structured Controversial Dialogues, The TESL Journal, http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Zainuddin-Controversial.html)FS Structured controversy can enhance the development of many skills that are central to academic learning. These

skills include: searching for information and new experiences to resolve a dilemma or an uncertainty; organizing information; preparing an advocacy position and rationalizing the position; seeing issues from a different perspective and learning to debate the merits of each position ; and synthesizing issues and conceptualizing a new position or reaching consensus based on careful analysis and evaluation of all positions of the issue. By using structured controversy, students' curiosity for searching for solutions to the problem will be sparked, engaging them in active learning that will help develop their understanding and appreciation of diverse points of views . It also requires students to use complex reasoning and critical thinking skills . As a result, students are exposed to a greater range of ideas that will help them to generate creative solutions and new conclusions to their controversial problem .

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

Switch Side debating has had real world influences on decision making the EPA has used it to learn more about the path necessary for addressing environmental crises Mitchell 10 Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of Communication at the University of Pittsburgh, where he also

directs the William Pitt Debating Union. (Gordon R. Mitchell, Switch-Side Debating Meets Demand-Driven Rhetoric of Science, Rhetoric & Public Affairs Vol. 13, No. 1, 2010, pp. 95120. http://www.pitt.edu/~gordonm/JPubs/Mitchell2010.pdf) RaPa T h e U.S. intelligence communitys Analytic Outreach initiative implements what Ronald Walter Greene and Darrin Hicks call switch-

--real world

side debatinga critical thinking exercise where interlocutors temporarily suspend belief in their convictions to bring forth multiple angles of an argument. Drawing on Foucault, Greene and Hicks classify switch-side debating as a cultural technology, one laden with ideological baggage. Specifically, they claim that switch-side debating is invested with an ethical substance and that participation in the activity inculcates ethical obligations intrinsic to the technology, including political liberalism and a worldview colored by American exceptionalism. On first blush, the fact that a deputy U.S. director of national intelligence is attempting to deploy this cultural technology to strengthen secret intelligence tradecraft in support of U.S. foreign policy would seem to qualify as Exhibit B in support of Greene and Hickss general thesis. Yet the picture grows more complex when one considers what is happening over at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), where environmental scientist Ibrahim Goodwin is collaborating with John W. Davis on a project that uses switch-side debating to clean up air and water. In April 2008, that initiative brought top intercollegiate debaters from four universities to Washington, D.C., for a series of debates on the topic of water quality, held for an audience of EPA subject matter experts working on interstate river pollution and bottled water issues. An April 2009 follow-up event in Huntington Beach, California, featured another debate weighing the relative merits of monitoring versus remediation as beach pollution strategies. We use nationally ranked intercollegiate debate programs to research and present the arguments, both pro and con, devoid of special interest in the outcome, explains Davis. In doing so, agency representatives now remain squarely within the decision-making role thereby neutralizing overzealous advocacy that can inhibit learned discourse. The intelligence community and EPA debating

initiatives vary quite a bit simply by virtue of the contrasting policy objectives pursued by their sponsoring agencies (foreign policy versus environmental protection). Significant process-level differences mark of the respective initiatives as well; the former project entails largely one-way interactions designed to sluice insight from open sources to intelligence analysts working in classified environments and producing largely secret assessments. In contrast, the EPAs debating initiative is conducted through public forums in a policy process required by law to be transparent. h is granularity troubles Greene and Hickss deterministic framing of switch-side debate as an ideologically smooth and consistent cultural technology. In an alternative approach, this essay positions debate as a malleable method of decision making, one utilized by different actors in myriad ways to pursue various purposes. By bringing forth the texture inherent in the associated messy mangle of practice, 8 such an approach has potential to deepen our understanding of debate as a dynamic and contingent, rather than static, form of rhetorical performance. Juxtaposition of the intelligence community and EPA debating initiatives

illuminates additional avenues of inquiry that take overlapping elements of the two projects as points of departure.

Both tackle complex, multifaceted, and technical topics that do not lend themselves to reductionist, formal analysis, and both tap into the creative energy latent in what Protagoras of Abdera called dissoi logoi, the process of learning about a controversial or unresolved issue by airing opposing viewpoints. 9 In

short, these institutions are employing debate as a tool of deliberation, seeking outside expertise to help accomplish their aims. Such trends provide an occasion to revisit a presumption commonly held among theorists of deliberative democracythat debate and deliberation are fundamentally opposed practice sas the intelligence communitys Analytic Outreach program and the EPAs debating initiatives represent examples where debating exercises are designed to facilitate, not frustrate, deliberative goals. Switch side debate is key to real world decision-making about complex issuesEPA public debate proves Mitchell 10 Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of Communication at the University of Pittsburgh, where he also

directs the William Pitt Debating Union. (Gordon R. Mitchell, Switch-Side Debating Meets Demand-Driven Rhetoric of Science, Rhetoric & Public Affairs Vol. 13, No. 1, 2010, pp. 95120. http://www.pitt.edu/~gordonm/JPubs/Mitchell2010.pdf) RaPa A debate scholar need not agree with Lords full-throated criticism of the intelligence community (he goes on to observe that it bears an alarming resemblance to organized crime) to understand that participation in the communitys Analytic Outreach program may

serve the ends of deliberation, but not necessarily democracy, or even a defensible politics. Demand-driven rhetoric of science necessarily raises

questions about whats driving the demand, questions that scholars with relevant expertise would do well to ponder carefully before embracing invitations to contribute their argumentative expertise to deliberative projects. By the same token, i t would be prudent to bear in mind that the

technological determinism about switch-side debate endorsed by Greene and Hicks may tend to latten reflexive assessments regarding the wisdom of supporting a given debate initiative as the next section illustrates, manifest differences

among initiatives warrant context-sensitive judgments regarding the normative political dimensions featured in each case.106 Rhetoric & Public Affairs Public Debates in the EPA Policy Process h e preceding analysis of U.S. intelligence community debating initiatives highlighted how analysts are challenged to navigate discursively the heteroglossia of vast amounts of different kinds of data lowing through intelligence streams. Public policy planners are

tested in like manner when they attempt to stitch together institutional arguments from various and sundry inputs ranging from expert testimony, to historical precedent, to public comment. Just as intelligence managers find that algorithmic,

formal methods of analysis ot en dont work when it comes to the task of interpreting and synthesizing copious amounts of disparate data, public-policy planners encounter similar challenges. In fact, the argumentative turn in public-policy planning elaborates an approach to

public-policy analysis that foregrounds deliberative interchange and critical thinking as alternatives to decisionism, the formulaic application of objective decision algorithms to the public policy process. Stating the matter plainly, Majone suggests,

8

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name]

whether

Suo

in written or oral form, argument is central in all stages of the policy process . Accordingly, he notes, we miss a great deal if we try to understand policy-making solely in terms of power, influence, and bargaining, to the exclusion of debate and argument. 51 One can see similar rationales driving Goodwin and Daviss EPA debating project, where debaters are

invited to conduct on-site public debates covering resolutions crafted to reflect key points of stasis in the EPA decision-making process. For example, in the 2008 Water Wars debates held at EPA headquarters in Washington, D.C., resolutions were crafted to focus attention on the topic of

water pollution, with one resolution focusing on downstream states authority to control upstream states discharges and sources of pollutants, and a second resolution exploring the policy merits of bottled water and toilet paper taxes as revenue sources to fund water infrastructure projects. In the first debate on interstate river pollution, the team of Seth Gannon and Seungwon Chung from Wake Forest University argued in favor of downstream state control, with the Michigan State University team of Carly Wunderlich and Garrett Abelkop providing opposition. In the second debate on taxation policy, Kevin Kallmyer and Matthew Struth from University of Mary Washington defended taxes on bottled water and toilet paper, while their opponents from Howard University, Dominique Scott and Jarred McKee, argued against this proposal. Relecting on the project, Goodwin noted how the intercollegiate debaters ability to act as honest brokers in the policy arguments contributed positively to internal EPA deliberation on both issues. 52 Davis observed that since the invited debaters didnt have a dog in the fight, they were able to give voice to previously buried arguments that some EPA subject matter experts felt reticent to elucidate because of their institutional affiliations. 53 Such findings are consistent with the views of policy analysts advocating the argumentative turn in policy planning. As Majone claims, Dialectical confrontation between generalists and experts often succeeds in bringing out unstated assumptions, conflicting interpretations of the facts, and the risks posed by new projects. 54 Frank Fischer goes even further in this context, explicitly appropriating rhetorical scholar Charles Willards concept of argumentative

epistemics to flesh out his vision for policy studies: Uncovering the epistemic dynamics of public controversies would allow for a more enlightened understanding of what is at stake in a particular dispute, making possible a sophisticated evaluation of the various viewpoints and merits of different policy options. In so doing, the differing, often tacitly held contextual perspectives and values could be juxtaposed; the viewpoints and demands of experts, special interest groups, and the wider public could be directly compared; and the dynamics among the participants could be scrutizined. This would by no means sideline or even exclude scientific assessment; it would only situate it within the framework of a more comprehensive evaluation. 55 As Davis notes, institutional constraints present within the EPA communicative milieu can complicate ef orts to provide a full airing of all relevant arguments pertaining to a given regulatory issue. Thus, intercollegiate debaters can play key roles in retrieving and amplifying positions that might

otherwise remain sedimented in the policy process.The dynamics entailed in this symbiotic relationship are underscored by deliberative

planner John Forester, who observes, If planners and public administrators are to make democratic political debate and argument possible, they will need strategically located allies to avoid being fully thwarted by the characteristic self-protecting behaviors of the planning organizations and bureaucracies within which they work. 56 Here, an institutions need for strategically located allies to support deliberative practice constitutes the demand for rhetorically informed expertise, setting up what can be considered a demand-driven rhetoric of science. As an instance of rhetoric of science

scholarship, this type of switch-side public debate 57 differs both from insular contest tournament debating, where the main focus is on

the pedagogical benefit for student participants, and first-generation rhetoric of science scholarship, where critics concentrated on unmasking the rhetoricity of scientific artifacts circulating in what many perceived to be purely technical spheres of knowledge production. 58 As a form of demand-driven rhetoric of science, switch-side debating connects directly with the communication fields performative tradition of

argumentative engagement in public controversya different route of theoretical grounding than rhetorical criticisms tendency to locate its foundations in the English fields tradition of literary criticism and textual analysis. 59 Given this genealogy, it is not surprising to learn how Daviss response to the EPAs institutional need for rhetorical expertise took the form of

a public debate proposal, shaped by Daviss dual background as a practitioner and historian of intercollegiate debate. Davis competed as an undergraduate policy debater for Howard University in the 1970s, and then went on to enjoy substantial success as coach of the Howard team in the new millennium. In an essay reviewing the broad sweep of debating history, Davis notes, Academic debate began at least 2,400 years ago when the scholar Protagoras of Abdera (481411 bc), known as the father of debate, conducted debates among his students in Athens. 60 As John Poulakos points out, older Sophists such as Protagoras taught Greek students the value of dissoi logoi, or pulling apart complex questions by

debating two sides of an issue. 61 The few surviving fragments of Protagorass work suggest that his notion of dissoi logoi stood for the principle that two accounts [logoi] are present about every thing, opposed to each other, and further, that humans could measure the relative soundness of knowledge claims by engaging in give-and-take where parties would make the weaker argument stronger to activate the generative aspect of rhetorical practice , a

key element of the Sophistical tradition. 62

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

Switch side debate is essential to critical thinking skills Harrigan 8 NDT champion, debate coach at UGA (Casey, thesis submitted to Wake Forest Graduate Faculty for Master of Arts in Communication, A

defense of switch side debate, http://dspace.zsr.wfu.edu/jspui/bitstream/10339/207/1/harrigancd052008, p. 57-59)RaPa

-critical thinking

Critics of SSD have argued that debating both sides is a tactic of cooption by dominant beliefs because speaking on behalf of evil ideas moderates extreme views. Instead of sharpening and refining the prior beliefs of debaters, the argument goes, engaging in switch side debating changes the beliefs of students, slowly drawing them close[r] to the middle (Massey 2006). Mirroring the broader critical move toward a depoliticized expression of struggles, they argue that this is undesirable

because only extreme views are pure, in the sense that they avoid entanglement in bureaucratic 36 structures of government (Boggs 1997, p. 773). Essentially, the argument boils down to brainwashin g: switching sides causes students to abandon their original

(presumably correct) beliefs in favor of more moderate and less politically effective idea s. Three responses effectively dispatch with this criticism and support the benefits of SSD. First, the foundational premise of the case for switch side debating indicts the notion that true conviction can be held prior to a rigorous analysis of all sides of an issue through debating both sides. As far back as A. C. Baird (1955), proponents of switch side debating have argued that conviction was a result of reasoned consideration of the issues surrounding a particular policy rather than a pre-condition for it . For instance, Baird argues, Sound conviction... should stem from mature reflection. Discussion and debate facilitate the maturing of such reflective thinking and conviction (1955, p. 6). Many debaters, especially those new to collegiate debate, do not yet have calcified opinions about many controversial subjects. Instead, they develop their beliefs over time, as they spend time thinking through the nuances of each relevant argument in preparation for competitive debating . By arguing on behalf of both the affirmative and the negative sides of a given resolution, switch side debaters are exposed to many avenues to test their initial thoughts on controversial subjects. Traditionally, the formation of belief in this manner has coincided more closely with the meaning of conviction . Defined as beliefs that are formed as a result of exposing

fallacies through the give-and-take of rebuttal, sound convictions can only be truly generated by the reflexive thinking spurred by debating both sides.

While some students may honestly believe that they have thoroughly considered the merits of a particular opinion before arguing for or against it in a debate, experimenting with ideas in a competitive SSD is still a necessary endeavor. Only in debate, a relatively isolated political space, are many arguments able to be presented in an ideally open, no-holdsbarred manner (Coverstone 1995). Moreover, when faced with the prospect of being forced to advocate a position, students receive the necessary motivation (through competitive and other impulses) to thoroughly research all of the complexities of a given subject. Also, through the requirement of advocacy, students are encouraged to actively listen, a crucial element of rich argumentative engagement (Lacy 2002). In the end, the switch side debater emerges with a deeper understanding of more sides of an issue and may be ready to come to some degree of conclusion and conviction about which side to support. Conviction generated through debating both sides is almost universally preferable to dogmatic and non-negotiable assertions of belief (Baird 1955, p. 6). Switching sides grounds belief in reasonable reflective thinking; it teaches that decisions should not be rendered until all positions and possible consequences have been considered in a reasoned manner. This method is closely linked to the value that debate places on critical thinking. Unsurprisingly, many authors have noted the importance of SSD for generating such

rigorous decision-making skills (Muir 1993; Parcher 1998; Rutledge 2002; Speice & Lyle 2003; English, Llano, Mitchell, Morrison, Rief and Woods 2007).

The critical thinking taught by SSD provides the ultimate check against dangerous forms of cooption. Over time, certain arguments will prevail over others only if they have a strong enough logical foundation to withstand thorough scrutiny. Debaters will change their minds to support the moderate side of certain positions only ifafter reasoned reflection and sound convictiondoing so is found to be preferable. While such a marketplace of ideas may be marked by some imperfections, one of its most effective incarnations is undoubtedly in academic debate rounds. There, appeals to wealth, status, and power are minimized by a focus on logic and formal rules, which protect the ability of all participants to contribute in an honest and open manner. As a result , it should be assumed that the insights generated through debates dialectic process will be generally correct and that any shifting beliefs are the reflection of a social good (the replacement of false ideas with truth). Conceiving of conviction in this manner redefines the role of debate into what Baird calls an

educational procedure: the formation of a pedagogical playground to experiment with alternative ideas and coalesce assertions and unwarranted beliefs into sound conviction (1966, p. 6). Treating debate as a training ground for advocacy and decision-making has several benefits:

it allows debaters the conceptual flexibility to experiment with minority and extreme ideas, protects them from outside influences, and buys them time before they are forced to publicly put forward their opinion s (Coverstone 1995). As a result, the primary focus of the activity shifts from arguing to deciding, giving critical thinking its crucial importance. A fundamental premise of the anti-SSDs claim about cooption is thoroughly indicted: it is impossible to lose ones convictions before they have truly been discovered. Critical thinking is at an all-time low--- reversing that trend now prevents serial policy failure and combats cognitive biases Butt 10 Ph.D. in Philosophy at Wayne State University. Attended George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, graduating with degrees in International

Studies and Communication in 1993. Neil completed his Masters Degree in Communication and Policy Analysis, also from GMU, in 2000. He has coached policy debate at the high school and college level since 1988, and has taught classes at the college level since 1993, including public speaking, interpersonal

10

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

and small group communication, argumentation and debate, research methods, and rhetorical criticism. (Neil Stuart, Argument Construction, Argument Evaluation, And Decision-Making: A Content Analysis Of Argumentation And Debate Textbooks, (2010), Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 77. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/77) RaPa Given the obvious importance of critical thinking and decision-making, the attention they have received in our educational system is not surprising. Despite this attention, critical thinking levels are disappointingly low in the United States. Recent studies show students score

low on tests of critical thinking ability (Brannigan, 2009; Krueger, 2009) and, more specifically, students demonstrate an inability to understand and evaluate arguments (Shellenbarger, 2009; Viadero, 2009). Even experts are susceptible to erroneous decisions due to lapses in critical thinking (Gilovich, 1991). In addition to lacking certain critical thinking skills, people also allow certain obstacles to interfere with their critical thinking ability . For example, Elder and Paul (2007) note that most people not taught to think analytically. Instead, they are conditioned to make certain responses, rather than think freely and reflexively, and are often motivated by fear or other emotions (Paul & Elder, 2006a). Additionally, due to cognitive dissonance, people have a hard time accepting that they have made a bad decision because it conflicts with their view of themselves as intelligent (Tavris & Aronson, 2007). This is consistent with Elder and Pauls (2004) observation that people are susceptible to what they call egocentric thinking, privileging their own perceptions and intuitions over those of others. Unfortunately, people are unaware of these egocentric assumptions unless they are trained to recognize them, and this creates blind spots for otherwise skilled thinkers. As a result, people have a natural tendency to ignore their own mistakes, which not only lead to policy failures and exacerbate them, but also can hinder opportunities to correct those mistakes (Tavris & Aronson, 2007). Increasing complexity means that critical thinking is necessary to solve global problems Butt 10 Ph.D. in Philosophy at Wayne State University. Attended George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, graduating with degrees in International

Studies and Communication in 1993. Neil completed his Masters Degree in Communication and Policy Analysis, also from GMU, in 2000. He has coached policy debate at the high school and college level since 1988, and has taught classes at the college level since 1993, including public speaking, interpersonal and small group communication, argumentation and debate, research methods, and rhetorical criticism. (Neil Stuart, Argument Construction, Argument Evaluation, And Decision-Making: A Content Analysis Of Argumentation And Debate Textbooks, (2010), Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 77. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/77) RaPa According to Paul and Willsen (1995), peoples desire for predictability and stability often encourage them to look backward

for tried and true answers, but since the world constantly changes, and new technology accelerates that change, the past can not always serve as a reliable guide, so people have to continually reassess their environment and their approaches to it. Makau and Marty (2001) have argued that, while we cannot control all of these changing external circumstances, we can respond to them proactively through critical thinking, allowing people to retain some control, and to meaningfully change their minds and their lives (p. 11). They argued that it is a source of empowerment and critical for people attempting to transform their own lives. Some might argue that not everyone needs to be able to deal with complex issuesthat it is the role of policy makers and their advisers; ordinary citizens do not have to be able to evaluate the same kinds of complex public policy question s. There are a number of problems with this objection. First, even though it is true that not everyone will become a leader or policy decision maker, in a democratic system, everyone still has to vote for the people who will become those decision-makers or who will appoint those decision-makers . The voting

process works much better if people know enough about the issues to evaluate the candidates (even though it is unrealistic to expect them to have the same level of expertise as those candidates). Second, we have to provide an opportunity for the people who will become leaders and

policymakers to develop their decision-making skills, and since we don't know ahead of time who these people will be we need to make these opportunities as widely available as possible. The more people we have with these skills, the more options we will have when it comes time to choose our leaders and decision-makers. Third, reaching as many students as possible also helps avoid dangers that could develop because of disparities in critical thinking ability. For example, 14 Paul and Willsen (1995) have argued that reaching a large segment of the public is necessary to prevent an ideological elite from dominating and oppressing the rest of the population: Critical thinking is ancient, but until now its practice was for the elite minority, for the few. But the few, in possession of superior power of disciplined thought, used it as one might only expect, to advance the interests of the few. We can never expect the few to become the longterm benevolent caretakers of the many. The many must become privy to the superior intellectual abilities, discipline, and traits of the traditional privileged few. Progressively, the power and accessibility of critical thinking will become more and more apparent to more and more people, particularly to those who have had limited access to the educational opportunities available to the fortunate few. (p. 16) Fourth, decision-making skills are useful to everyone, even if we limit decision-making to the context of making policy decisions. While we normally think of policymaking as referring to national or international policies, the term really just means a course of action or a plan. Everyone has to make decisions about what

they're going to do and decisions about what college to attend or which apartment to rent involves comparing advantages and disadvantages just as certainly as decisions about national and international policy do.

11

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

Our model of switch-side debate is on-balance good because it fosters critical thinking skills and expands our knowledge. Keller, et. al, 01 Asst. professor School of Social Service Administration U. of Chicago

(Thomas E., James K., and Tracly K., Asst. professor School of Social Service Administration U. of Chicago, professor of Social Work, and doctoral student School of Social Work, Student debates in policy courses: promoting policy practice skills and knowledge through active learning, Journal of Social Work Education, Spr/Summer 2001, EBSCOhost) The results of the surveys suggest that debates have value as an active learning strategy to enhance student learning. On survey questions and in written comments, students debates as a class assignment. Most indicated that participation

--ext. solves critical thinking

expressed satisfaction with the debates. The majority of students were pleased with the in the debates raised the level of their policy skills and

knowledge. In addition, the educational value of debates was rated as higher than more traditional assignments. It should be noted, however, that a desire

to report favorably on class experiences may have influenced reported satisfaction with the debates (i.e., acquiescence bias). Student comments supported the view that debates promote critical thinking by encouraging serious consideration of both sides of a policy

issue. Comments also indicated that the active learning approach had generated more classroom interest and energy than usual. On the other hand, some

comments noted how the debates might have detracted from a positive learning experience. All four hypotheses regarding changes in student-rated knowledge were supported by the analysis. Students reported statistically significant increases in knowledge on topics covered

during the course--a result which is reassuring for the instructors. Gains in self-reported knowledge from simply observing debates were equivalent to

gains based on traditional forms of instruction. Observing a debate appears comparable to acquiring information through a class lecture or discussion. By contrast, debate participation generated significantly greater increases in self-reported knowledge than were

obtained by observing debates or by learning through traditional forms of instruction. This result , which is consistent with the principles of experiential learning, suggests the educational advantage of using debates to engage students in learning.

The findings are noteworthy considering the use of conservative nonparametric statistics on a small sample. However, the results should be interpreted somewhat cautiously due to certain study limitations. First, the dependent variable was self-reported and highly subjective in nature. The study did not contain objective measures of knowledge, and the findings pertain only to students' self-perceptions of their knowledge regarding particular topics. Second, although attrition from pretest to posttest was not associated with the pretest measures, differential attrition related to unmeasured factors, including objective knowledge of the topics, is a potential source of bias. Third, the assumption of independence among cases may be questionable given that students worked closely as members of debate teams. Finally, other plausible explanations for the general increase in knowledge over time, besides taking the class, cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, the differential improvement in self-rated knowledge in favor of debaters would still be a credible finding, and this was a main objective of the analysis. Conclusion The purposes of this article were to examine the potential of student debates for fostering the development of policy practice knowledge and skills, to demonstrate that debates can be effectively incorporated as an in-class assignment in a policy course, and to report findings on the educational value and level of student satisfaction with debates. Based on a review of the literature, the authors' experience conducting debates in a course, and the subsequent evaluation of those debates, the authors believe the development of policy practice skills and the acquisition of substantive knowledge can be advanced through structured student debates in policy-oriented courses. The authors think debates on important policy

questions have numerous benefits: prompting students to deal with values and assumptions, encouraging them to investigate and analyze competing alternatives, compelling them to advocate a particular position, and motivating them to articulate a point of view in a persuasive manner. We think engaging in these analytic and persuasive activities promotes greater knowledge by stimulating active participation in the learning process.

However, the use of debates in a classroom setting is not without certain drawbacks. Schroeder and Ebert (1983) noted several limitations which were also encountered in this experience. First, staging debates presents logistical challenges for the instructor. These administrative concerns include creating teams, selecting topics, determining the debate format, and scheduling. Second, the amount of time devoted to the specific topic of a debate can detract from covering a wider scope of course material. Third, although debating encourages the examination of issues from two opposing positions, many policy dilemmas can be approached from several angles. A structured debate does not necessarily foster a multidimensional examination of policy options. Fourth, as in most group projects, some debate team members may have contributed more to the effort than others. Finally, the competitive aspects of debating may polarize the issue. For those interested in using debates as an instructional technique, the importance of thorough advance planning with respect to the mechanics of conducting the debates must be stressed. Flexibility to make adjustments during the process is equally important. Special attention should be given to debriefing sessions after debates to discuss perceptions of the debate experience, areas of common agreement, and possibilities for policy compromise and consensus. The integration of opposing views into a coherent and purposeful course of action is a central feature of the theoretical framework presented earlier, and students expressed a need for more resolution and closure. For example, one student suggested, "I think it would be more effective to do an active brainstorming/planning session for identifying solutions/alternatives following the debates." The final word on debates should come from students themselves. In the debriefing session immediately following a debate, one student stated,

"I thought the debate was good because it forced me to articulate the position, and that is something we will need to do to be advocates." Another student described how her opinion of debating changed, "When I first heard about this assignment, I really

questioned its value. I thought it would be a waste of class time. But I learned so much about family preservation services. I learned more than I ever would have any other way."

12

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

Switch side debate solves dogmatism and prevents authoritative discourseturns why the aff is key Hanghoj 8 Thorkild Hanghj, Copenhagen, 2008 Since this PhD project began in 2004, the present author has been affiliated with DREAM (Danish

Research Centre on Education and Advanced Media Materials), which is located at the Institute of Literature, Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Southern Denmark. Research visits have taken place at the Centre for Learning, Knowledge, and Interactive Technologies (L-KIT), the Institute of Education at the University of Bristol and the institute formerly known as Learning Lab Denmark at the School of Education, University of Aarhus, where I currently work as an assistant professor. http://static.sdu.dk/mediafiles/Files/Information_til/Studerende_ved_SDU/Din_uddannelse/phd_hum/afhandlinger/2009/ThorkilHanghoej.pdf Herm

-dogmatism

One of the key elements of dialogical pedagogy, and consequently a dialogical game pedagogy, is based upon the Bakhtinian notion of authority. In his writings, Bakhtin often distinguishes between authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse (Bakhtin, 1981, 1984a). Authoritative discourse refers to those forms of language use which present themselves as unchallengeable orthodoxy by formulating positions that are not open to debate. Bakhtinexemplifies this with political dogma that demands our unconditional allegiance (Bakhtin, 1981: 343). According to Eugene Matusov, classroom examples of authoritative discourse also include intolerance, speaking for others, an unwillingness to listen to and genuinely question others, the failure to test ones own ideas and assumptions, and the desire to impose ones own views on others (Matusov, 2007: 231). Internally persuasive discourse, in contrast, refers to language use directed towards mutual communication and the mutual construction of knowledge: In the everyday rounds of our consciousness, the internally persuasive word is half-ours and halfsomeone-else's (Bakhtin, 1981: 345). In this way, internally persuasive discourse marks a creative border zone based on the impossibility of any word ever being final, and for this reason it is able to reveal ever newer ways to mean (Bakhtin, 1981: 346). But internally persuasive discourse cannot be reduced to the mere appropriation of the ideas and words of others, as it requires the ability to be involved in and embody how diverse voices collide with each other in a dialogue that tests these ideas (Matusov, 2007: 230). Thus, internally persuasive discourse always requires some form of dialogical and critical exposure that can be supported by the interplay of different voices in a classroom setting.

13

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

--dogmatism ext.

Argument deliberation on a topic from multiple perspectives is keythe alternative is polarization and dogmatism Talisse 5

(Talisse, Robert, philosophy professor at Vanderbilt, Deliberativist Response to Activist Challenges, Philosophy and Social Criticism, vol 31, no.4)FS

Group polarization is a well-documented phenomenon that has been found all over the world and in many diverse tasks; it means that members of a deliberating group predictably move towards a more extreme point in the direction indicated by the members predeliberation tendencies (Sunstein, 2003: 812). Importantly, in groups that engage in repeated discussions over time, the polarization is even more pronounced (2003: 86). Hence discussion in a small but devoted activist enclave that meets regularly to strategize and protest should produce a situation in which individuals hold positions more extreme than those of any individual member before the series of deliberations began (ibid.).17 The fact of group polarization is relevant to our discussion because the activist has proposed that he may reasonably decline to engage in discussion with those with whom he disagrees in cases in which the requirements of justice are so clear that he can be confident that he has the truth. Group polarization suggests that deliberatively confronting those with whom we disagree is essential even when we have the truth. For even if we have the truth, if we do not engage opposing views, but instead deliberate only with those with whom we agree, our view will shift progressively to a more extreme point, and thus we lose the truth. In order to avoid polarization, deliberation must take place within heterogeneous argument pools (Sunstein, 2003: 93). This of course does not mean that there should be no groups devoted to the achievement of some common political goal; it rather suggests that engagement with those with whom one disagrees is essential to the proper pursuit of justice. Insofar as the activist denies this, he is unreasonable. We must have a forum with which to test ideasactivism becomes hollow and obstructive when it refuses to engage in a discussion on both sides on an issue. This is the best education for activism outside of debate. Talisse 5

(Talisse, Robert, philosophy professor at Vanderbilt, Deliberativist Response to Activist Challenges, Philosophy and Social Criticism, vol 31, no.4)FS The argument thus far might appear to turn exclusively upon different conceptions of what reasonableness entails. The deliberativist view I have sketched holds that reasonableness involves some degree of what we may call epistemic modesty. On this view, the reasonable citizen seeks to have her

beliefs reflect the best available reasons, and so she enters into public discourse as a way of testing her views against the objections and questions of those who disagree; hence she implicitly holds that her present view is open to reasonable critique and that others who hold opposing views may be able to offer justifications for their views that are at least as strong as her reasons for her own. Thus any mode of politics that presumes that discourse is extraneous to questions of justice and justification is unreasonable. The activist sees no reason to accept this. Reasonableness for the activist consists in

the ability to act on reasons that upon due reflection seem adequate to underwrite action; discussion with those who disagree need not be involved.

According to the activist, there are certain cases in which he does in fact know the truth about what justice requires and in which there is no room for reasoned objection. Under such conditions, the deliberativists demand for discussion can only obstruct justice; it is therefore irrational . It may seem that we have reached an impasse. However, there is a further line of criticism that the activist must face. To the activists view that at least in certain situations he may reasonably decline to engage with persons he disagrees with (107), the deliberative democrat can raise the phenomenon that Cass Sunstein has called group polarization (Sunstein, 2003; 2001a: ch. 3; 2001b: ch. 1). To explain: consider that political activists cannot eschew deliberation altogether ; they often engage in rallies, demonstrations, teach-ins, workshops, and other activities in which they are called to make public the case for their views. Activists also must engage in deliberation among themselves when deciding strategy. Political movements must be organized, hence those involved must decide upon targets, methods, and tactics; they must also decide upon the content of their pamphlets and the precise messages they most wish to convey to the press. Often the audience in both of these deliberative contexts will be a self-selected

and sympathetic group of like-minded activists.

Switch side is key to meaningful dialogue Harrigan 8 NDT champion, debate coach at UGA (Casey, thesis submitted to Wake Forest Graduate Faculty for Master of Arts in Communication, A

defense of switch side debate, http://dspace.zsr.wfu.edu/jspui/bitstream/10339/207/1/harrigancd052008, p. 57-59)RaPa

It has been argued that many of the benefits of switching sides could theoretically be achieved through alternative means (Murphy 1957; 1963). After all, debaters should live well-rounded lives and have many academic pursuits outside of the competitive arena. The

benefits of tolerance and critical thinking generated through intensive research and understanding of the oppositions arguments might be created by simply spending time reading and understanding multiple sides of complex positions. Practice rounds that simulate actual debating but are conducted in the privacy and seclusion of the debate office away from public tournaments can expand debaters experiences without requiring SSD. All of this, the anti-SSD

advocates such as Murphy say, can capture the benefit of debating both sides without risking its ethical or social downsides. However, even if many of the strengths of switch side debate can be achieved in other ways, it does not

14

[File Name] Lexington 2009-2010

[Tournament Name] Suo

mean that they necessarily would be. Some students will seek out avenues to broaden their range of thinking and encounter beliefs that are contrary to their own. Others will not. For many students, the competitive aspects of contest debating are the primary motivation for their initial engagement with the tedious and complex literature featured in policy debates. Without the push of SSD and the competitive drive associated with wins and loses of competitive contest debating, most would not step outside their narrow personal beliefs and enter into a meaningful dialogue with opposing arguments. The task of educators is to make the tough choices about how to direct the learning of their

students in order to maximize their educational benefit. SSD is a timetested way to do that.