Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Homousios Agennetos Excursus PN 2 ECF 3 V14

Încărcat de

TaviDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Homousios Agennetos Excursus PN 2 ECF 3 V14

Încărcat de

TaviDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

57

EXCURSUS ON THE WORD HOMOUSIOS.

The Fathers of the Council at Nice were at one time ready to accede to the request of some of the bishops and use only scriptural expressions in their definitions. But, after several attempts, they found that all these were capable of being explained away. Athanasius describes with much wit and penetration how he saw them nodding and winking to each other when the orthodox proposed expressions which they had thought of a way of escaping from the force of. After a series of attempts of this sort it was found that something clearer and more unequivocal must be adopted if real unity of faith was to be attained; and accordingly the word homousios was adopted. Just what the Council intended this expression to mean is set forth by St. Athanasius as follows: That the Son is not only like to the Father, but that, as his image, he is the same as the Father; that he is of the Father; and that the resemblance of the Son to the Father, and his immutability, are different from ours: for in us they are something acquired, and arise from our fulfilling the divine commands. Moreover, they wished to indicate by this that his generation is different from that of human nature; that the Son is not only like to the Father, but inseparable from the substance of the Father, that he and the Father are one and the same, as the Son himself said: The Logos is always in the Father, and, the Father always in the Logos, as the sun and its splendor are inseparable. The word homousios had not had, although frequently used before the Council of Nice, a very happy history. It was probably rejected by the Council of Antioch, and was suspected of being open to a Sabellian meaning. It was accepted by the heretic Paul of Samosata and this rendered it very offensive to many in the Asiatic Churches. On the other hand the word is used four times by St. Irenaeus, and Pamphilus the Martyr is quoted as asserting that Origen used the very word in the Nicene sense. Tertullian also uses the expression of one substance (unius substanticoe) in two places, and it would seem that more than half a century before the meeting of the Council of Nice, it was a common one among the Orthodox.

58

Vasquez treats this matter at some length in his Disputations, and points out how well the distinction is drawn by Epiphanius between Synousios and Homousios , for synousios signifies such an unity of substance as allows of no distinction: wherefore the Sabellians would admit this word: but on the contrary homousios signifies the same nature and substance but with a distinction between persons one from the other. Rightly, therefore, has the Church adopted this word as the one best calculated to confute the Arian heresy. It may perhaps be well to note that these words are formed like oJmo>biov and oJmoio>biov, oJmognw>mwn and oJmoiognw>mwn etc., etc. The reader will find this whole doctrine treated at great length in all the bodies of divinity; and in Alexander Natalis (H.E. t. iv., Dies. xiv.); he is also referred to Pearson, On the Creed; Bull, Defense of the Nicene Creed; Forbes, An Explanation of the Nicene Creed; and especially to the little book, written in answer to the recent criticisms of Professor Harnack, by H. B. Swete, D.D., The Apostles Creed.

59

EXCURSUS ON THE WORDS gennhqe>nta ouj poihqe>nta, (J. B. Lightfoot. The Apostolic Fathers Part II. Vol. 2:Sec. I. pp. 90, et seqq.) The Son is here [Ignat. Ad. Eph. vii.] declared to be yennhto<v as man and ajge>nnhtov as God, for this is clearly shown to be the meaning from the parallel clauses. Such language is not in accordance with later theological definitions, which carefully distinguished between genhto>v and gennhto>v between ajge>nhtov and ajge>nnhtov; so that genhto>v ajge>ntov respectively denied and affirmed the eternal existence, being equivalent to ktisto>v a]ktistov, while gennhto>v, ajge>nnhtov described certain ontological relations, whether in time or in eternity. In the later theological language, therefore, the Son was gennhto>v even in his Godhead. See esp. Joann. Damasc. de Fid. Orth. 1:8 [where he draws the conclusion that only the Father is ajge>nnhtov and only the Son gennhto>v] There can be little doubt however, that Ignatius wrote gennhto>v kai< ajge>nnhtov though his editors frequently alter it into genhto<v kai< ajge>nnhtov For the Greek MS. still retains the double [Greek nun] v, though the claims of orthodoxy would be a temptation to scribes to substitute the single v. And to this reading also the Latin genitus et ingenitus points. On the other hand it cannot be concluded that translators who give factus et non factus had the words with one v, for this was after all what Ignatius meant by the double v, and they would naturally render his words so as to make his orthodoxy apparent. When Theodoret writes gennhto<v ejx ajgennh>tou it is clear that he, or the person before him who first substituted this reading, must have read gennhto<v kai< ajge>nnhtov for there would be no temptation to alter the perfectly orthodox genhto<v kai< ajge>nhtov nor (if altered) would it have taken this form. When the interpolator substitutes oJ mo>nov a]lhqino<v Qeo<v oJ ajge>nnhtov tou~ de< monogonou~v path<r kai< gennh>twr, the natural inference is that he too, had the forms in double v, which he retained, at the same time altering the whole run of the sentence so as not to do violence to his own doctrinal views; see Bull Def. Fid. Nic. 2:2 6. The quotation in Athanasius is more difficult. The MSS. vary, and his editors write genhto<v kai< ajge>nhtov. Zahn too, who has paid more attention to this point than any previous

60

editor of Ignatius, in his former work (Ign. V. Ant. p. 564), supposed Athanasius to have read and written the words with a single v, though in his subsequent edition of Ignatius (p. 338) he declares himself unable to determine between the single and double 5:I believe, however, that the argument of Athanasius decides in favor of the vv. Elsewhere he insists repeatedly on the distinction between kti>zein and genna~n justifying the use of the latter term as applied to the divinity of the Son, and defending the statement in the Nicene Creed gennhto<n ejk th~v sujsi>av tou~ patro<v to<n uiJon < oJmoou>sion (De Synod. 54, 1, p. 612). Although he is not responsible for the language of the Macrostich (De Synod. 3, 1, p. 590), and would have regarded it as inadequate without the oJmoou>sion yet this use of terms entirely harmonizes with his own. In the passage before us, ib. 46, 47 (p. 607), he is defending the use of homousios at Nicaea, notwithstanding that it had been previously rejected by the council which condemned Paul of Samosata, and he contends that both councils were orthodox, since they used homousios in a different sense. As a parallel instance he takes the word ajge>nnhtov which like homousios is not a scriptural word, and like it also is used in two ways, signifying either (1.) To< o}n men mh>te de< gennhqe<n mh>te o[lwv e]con to<n ai]tion or (2.) To< a]ktiston. In the former sense the Son cannot be called ajge>nn htovin the latter he may be so called. Both uses, he says, are found in the fathers. Of the latter he quotes the passage in Ignatius as an example; of the former he says, that some writers subsequent to Ignatius declare e[n to< ajge>nnhton oJ path<r, kai<ei+v oJ ejx aujto~u uiJov < gnh>siov, ge>nnhma alhqi>non k.t.l. [He may have been thinking of Clem. Alex. Strom. 6:7, which I shall quote below.] He maintains that both are orthodox, as having in view two different senses of the word ajge>nnhton and the same, he argues, is the case with the councils which seem to take opposite sides with regard to homousios . It is dear from this passage, as Zahn truly says, that Athanasius is dealing with one and the same word throughout; and, if so, it follows that this word must be ajge>nnhton, since ajge>nthton would be intolerable in some places. I may add by way of caution that in two other passages, de Decret. Syn. Nic. 28 (1, p. 184), Orat. c. Arian. 1:30 (1, p. 343), St. Athanasius gives the various senses of ajge>nnhton (for this is plain from the context), and that these passages ought not to be treated as parallels to the present passage which is concerned with the senses of ajge>nnhton. Much confusion is thus created, e.g. in Newmans notes on

61

the several passages in the Oxford translation of Athanasius (pp. 51 sq., 224 sq.), where the three passages are treated as parallel, and no attempt is made to discriminate the readings in the several places, but ingenerate is given as the rendering of both alike. If then Athanasius who read gennhto<v kai< ajge>nnhtov in Ignatius, there is absolutely no authority for the spelling with one v. The earlier editors (Voss, Useher, Cotelier, etc.), printed it as they found it in the MS.; but Smith substituted the forms with the single v, and he has been followed more recently by Hefele, Dressel, and some other. In the Casatensian copy of the MS., a marginal note is added, ajnagnwste>on ajge>nhtov tou~t e]sti mh< poihqei>v Waterland (Works, III., p. 240 sq., Oxf. 1823) tries ineffectually to show that the form with the double v was invented by the fathers at a later date to express their theological conception. He even doubts whether there was any such word as ajge>nnhtov so early as the time of Ignatius. In this he is certainly wrong. The MSS. of early Christian writers exhibit much confusion between these words spelled with the double and the single v. See e.g. Justin Dial. 2, with Ottos note; Athenag. Suppl. 4 with Ottos note; Theophil, ad Autol. 2:3, 4; Iren. 4:38, 1, 3; Orig. c. Cels. 6:66; Method. de Lib. Arbitr., p. 57; Jahn (see Jahns note 11, p. 122); Maximus in Euseb. Praep. Ev. 7:22; Hippol. Haer. 5:16 (from Sibylline Oracles); Clem. Alex. Strom 5:14; and very frequently in later writers. Yet notwithstanding the confusion into which later transcribers have thus thrown the subject, it is still possible to ascertain the main facts respecting the usage of the two forms. The distinction between the two terms, as indicated by their origin, is that ajge>nhtov denies the creation, and ajge>nnhtov the generation or parentage. Both are used at a very early date; e.g. ajge>nhtov by Parmenides in Clem. Alex. Strom. 5:l4, and by Agothon in Arist. Eth. Nic. 7:2 (comp. also Orac. Sibyll. prooem. 7, 17); and ajge>nnhtov in Soph. Trach. 61 (where it is equivalent to dusgenw~n Here the distinction of meaning is strictly preserved, and so probably it always is in Classical writers; for in Soph. Trach. 743 we should after Porson and Hermann read ajge>nhton with Suidas. In Christian writers also there is no reason to suppose that the distinction was ever lost, though in certain connections the words might be used convertibly. Whenever, as here in Ignatius, we have the double v where we should expect the single, we must ascribe the fact to the

62

indistinctness or incorrectness of the writers theological conceptions, not to any obliteration of the meaning of the terms themselves. To this early father for instance the eternal ge>nnhsiv of the Son was not a distinct theological idea, though substantially he held the same views as the Nicene fathers respecting the Person of Christ. The following passages from early Christian writers will serve at once to show how far the distinction was appreciated, and to what extent the Nicene conception prevailed in ante-Nicene Christianity; Justin Apol. 2:6, comp. ib. 13; Athenag. Suppl. 10 (comp. ib. 4); Theoph. ad. Aut. 2:3; Tatian Orat. 5; Rhodon in Euseb. H. E. 5:13; Clem. Alex. Strom. 6:7; Orig. c. Cels. 6:17, ib. 6:52; Concil. Antioch (A.D. 269) in Routh Rel. Sacr. III., p. 290; Method. de Creat. 5. In no early Christian writing, however, is the distinction more obvious than in the Clementine Homilies, 10:10 (where the distinction is employed to support the writers heretical theology): see also 8:16, and comp. 19:3, 4, 9, 12. The following are instructive passages as regards the use of these words where the opinions of other heretical writers are given; Saturninus, Iren. 1:24, 1; Hippol. Haer. 7:28; Simon Magus, Hippol. Haer. 6:17, 18; the Valentinians, Hippol. Haer. 6:29, 30; the Ptolemaeus in particular, Ptol. Ep. ad. Flor. 4 (in Stierens Ireninians, Hipaeus, p. 935); Basilides, Hippol. Haer. 7:22; Carpocrates, Hippol. Haer. 7:32. From the above passages it will appear that Ante-Nicene writers were not indifferent to the distinction of meaning between the two words; and when once the orthodox Christology was formulated in the Nicene Creed in the words gennhqe>nta ouj poihqe>nta, it became henceforth impossible to overlook the difference. The Son was thus declared to be gennhto>v but not genhto>v I am therefore unable to agree with Zahn (Marcellus, pp. 40, 104, 223, Ign. von Ant. p. 565), that at the time of the Arian controversy the disputants were not alive to the difference of meaning. See for example Epiphanius, Haer. 64:8. But it had no especial interest for them. While the orthodox party clung to the homousios as enshrining the doctrine for which they fought, they had no liking for the terms ajge>nnhtov and gennhto>v as applied to the Father and the Son respectively, though unable to deny their propriety, because they were affected by the Arians and applied in their own way. To the orthodox mind the Arian formula oujk h+n pri<n gennhqh>nai or some Semiarian formula hardly less dangerous, seemed always to be lurking under the expression Qeo<v gennhto>v as

63

applied to the Son. Hence the language of Epiphanius Haer. 73:19: As you refuse to accept our homousios because though used by the fathers, it does not occur in the Scriptures, so will we decline on the same grounds to accept your ajge>nnhtov. Similarly Basil c. Eunom. i., iv., and especially ib. further on, in which last passage he argues at great length against the position of the heretics, eij ajge>nntov, fasi<n oJ path>r gennhto<v de< oJ uiJov, ouj th~v aujth~v oujsi>av. See also the arguments against the Anomoeans in [Athan.] Dial. de Trin. illpassim. This fully explains the reluctance of the orthodox party to handle terms which their adversaries used to endanger the homousios. But, when the stress of the Arian controversy was removed, it became convenient to express the Catholic doctrine by saying that the Son in his divine nature was ge>nnhtov but not ge>nhtov. And this distinction is staunchly maintained in later orthodox writers, e.g. John of Damascus, already quoted in the beginning of this Excursus.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Bible and Poetry in Late Antique Mesopotamia: Ephrem's Hymns on FaithDe la EverandBible and Poetry in Late Antique Mesopotamia: Ephrem's Hymns on FaithÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Meyendorff - AN ORTHODOX VIEW ON MISSION AND INTEGRATIONDocument3 paginiJohn Meyendorff - AN ORTHODOX VIEW ON MISSION AND INTEGRATIONAndrija Lazarevic100% (1)

- Paladie - Dialoguri Despre Viata Sfantului Ioan Gura de AurDocument296 paginiPaladie - Dialoguri Despre Viata Sfantului Ioan Gura de AurAlin Goga50% (2)

- Second Council of Constantinople 553 AD Anathemas and Reincarnation CondemnedDocument24 paginiSecond Council of Constantinople 553 AD Anathemas and Reincarnation Condemnedcrdewitt100% (1)

- ST Basil The GreatDocument2 paginiST Basil The GreatStudents of the FathersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Migne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus. Series Graeca. Volume 161.Document642 paginiMigne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus. Series Graeca. Volume 161.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faith, the Fount of Exegesis: The Interpretation of Scripture in the Light of the History of Research on the Old TestamentDe la EverandFaith, the Fount of Exegesis: The Interpretation of Scripture in the Light of the History of Research on the Old TestamentEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- The Definitions of Unit 1Document10 paginiThe Definitions of Unit 1Kubra BagirovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6127 101Document317 pagini6127 101rebelu100% (2)

- (Paul Evdokimov) Arta Icoanei.O Teologie A FrumusetiiDocument54 pagini(Paul Evdokimov) Arta Icoanei.O Teologie A FrumusetiivirtualulÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Idea of Tradition in the Late Modern World: An Ecumenical and Interreligious ConversationDe la EverandThe Idea of Tradition in the Late Modern World: An Ecumenical and Interreligious ConversationÎncă nu există evaluări

- (PSB) 81 SF Maxim Marturisitorul - Scrieri IIDocument367 pagini(PSB) 81 SF Maxim Marturisitorul - Scrieri IIAndreiaPădureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alexei Khomiakov - Letters To William PalmerDocument62 paginiAlexei Khomiakov - Letters To William PalmerGiorgosby17100% (1)

- Severus, Patriarch of Antioch (512-538), in The Greek, Syriac, and Coptic TraditionsDocument20 paginiSeverus, Patriarch of Antioch (512-538), in The Greek, Syriac, and Coptic TraditionsJulia DubikajtisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Georgian AutochephalyDocument27 paginiGeorgian AutochephalyAlexandru MariusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Советизатия православияDocument21 paginiСоветизатия православияgumenaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cvetkovic - Time and EternityDocument17 paginiCvetkovic - Time and EternityVladimir CvetkovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Orthodox Christian MissionDocument3 paginiThe Orthodox Christian MissionselimirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The cult of the Virgin Ζωοδόχος Πηγή and its reflection in the painting of the Palaiologan eraDocument20 paginiThe cult of the Virgin Ζωοδόχος Πηγή and its reflection in the painting of the Palaiologan eraomoros2802Încă nu există evaluări

- Quasten - The Fathers' of The ChurchDocument2 paginiQuasten - The Fathers' of The ChurchPatrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Killian Analysis of The Conflict Between Russia and UkraineDocument7 paginiKillian Analysis of The Conflict Between Russia and UkrainerudibertÎncă nu există evaluări

- Once Upon A December (Lyrics) PDFDocument1 paginăOnce Upon A December (Lyrics) PDFa_kalliopiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ananias of Sirak (Hewsen 1968)Document15 paginiAnanias of Sirak (Hewsen 1968)ConstantinAkentievÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles and Practices of Diakonia inDocument16 paginiPrinciples and Practices of Diakonia inAlin Ionut Chiper100% (1)

- The Victory of The CrossDocument4 paginiThe Victory of The CrossDoug Floyd100% (1)

- Hexapla of Origen in The Encyclopedia of PDFDocument2 paginiHexapla of Origen in The Encyclopedia of PDFivory2011Încă nu există evaluări

- Autocephaly and Autonomy - John H. EricksonDocument21 paginiAutocephaly and Autonomy - John H. EricksonVasile AlupeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bede Irish Computistica and Annus Mundi PDFDocument23 paginiBede Irish Computistica and Annus Mundi PDFnarcis zarnescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Canons of Hippolytus: An English version, with introduction and annotation and an accompanying Arabic textDe la EverandThe Canons of Hippolytus: An English version, with introduction and annotation and an accompanying Arabic textÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1974 - John H. Reumann - Psalm 22 at The Cross. Lament and Thanksgiving For Jesus ChristDocument21 pagini1974 - John H. Reumann - Psalm 22 at The Cross. Lament and Thanksgiving For Jesus Christbuster301168Încă nu există evaluări

- Cutrone, Cyril's Mystagogical Catecheses and The Evolution of The Jerusalem AnaphoraDocument7 paginiCutrone, Cyril's Mystagogical Catecheses and The Evolution of The Jerusalem AnaphoraA TÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Heresy of Constantinople PapismDocument19 paginiThe Heresy of Constantinople Papismgpmachas100% (1)

- Karavidopoulos Ioannis, The Ecumenical Patriarchate's 1904 New Testament EditionDocument8 paginiKaravidopoulos Ioannis, The Ecumenical Patriarchate's 1904 New Testament EditionalmihaÎncă nu există evaluări

- An-Analysis-Of-Canon-82-Of-The-Council-Of-Trullo-Text-And-Context - Content File PDFDocument15 paginiAn-Analysis-Of-Canon-82-Of-The-Council-Of-Trullo-Text-And-Context - Content File PDFMelangell Shirley Roe-Stevens SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Salvation Outside Orthodoxy: Thoughts On The Article "Ecumenoclasm: Who Can Be Saved?"Document3 paginiOn Salvation Outside Orthodoxy: Thoughts On The Article "Ecumenoclasm: Who Can Be Saved?"HibernoSlavÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06 Tesu - Chipul Parintelui Duhovnicesc PDFDocument15 pagini06 Tesu - Chipul Parintelui Duhovnicesc PDFCristina LupuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Autokefalija Majendorf PDFDocument15 paginiAutokefalija Majendorf PDFΝεμάνια ΓιάνκοβιτςÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dilemmas of DiversityDocument246 paginiDilemmas of Diversityjareck18Încă nu există evaluări

- Emperor Michael Palaeologus and the West, 1258-1282: A Study in Byzantine-Latin RelationsDe la EverandEmperor Michael Palaeologus and the West, 1258-1282: A Study in Byzantine-Latin RelationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Proof: Chapter ExpectationsDocument483 paginiIntroduction To Proof: Chapter ExpectationsNimisha Anant100% (1)

- Cappadocians and PlatonismDocument3 paginiCappadocians and PlatonismHistorica VariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viata Si Activitatea Lui Anton Pann - Gem TeodorescuDocument18 paginiViata Si Activitatea Lui Anton Pann - Gem TeodorescuRotaru George-RaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antip, Anca-Mihaela, Evangheliarul de La Războieni. Text Eddition, Philological and Linguistic StudyDocument23 paginiAntip, Anca-Mihaela, Evangheliarul de La Războieni. Text Eddition, Philological and Linguistic StudyMihaiPopescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life and Teachings of ST Basil The Great - EditedDocument5 paginiLife and Teachings of ST Basil The Great - EditedcharlesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structures of Russian Orthodox ChurchesDocument27 paginiStructures of Russian Orthodox ChurchesMaria CastillonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Immoderate and Self-Absorbed Anti-Old Calendarist Zeal of The Innovative New CalendaristsDocument46 paginiThe Immoderate and Self-Absorbed Anti-Old Calendarist Zeal of The Innovative New CalendaristsHibernoSlavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eschatology and The Byzantine Liturgy by David M. Petras1 PDFDocument7 paginiEschatology and The Byzantine Liturgy by David M. Petras1 PDFsannicolas1952Încă nu există evaluări

- Nazi Foundations in Heidegger's Work: Faye, Emmanuel. Watson, Alexis. Golsan, Richard Joseph, 1952Document13 paginiNazi Foundations in Heidegger's Work: Faye, Emmanuel. Watson, Alexis. Golsan, Richard Joseph, 1952Seed Rock ZooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viorel - Coman - DUMITRU STĂNILOAE'S THEOLOGY OF THE WORLDDocument13 paginiViorel - Coman - DUMITRU STĂNILOAE'S THEOLOGY OF THE WORLDViorel ComanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ST Andrews CanonDocument9 paginiST Andrews CanonVOSKORÎncă nu există evaluări

- Go C Demetri As 1935 Eng PDFDocument3 paginiGo C Demetri As 1935 Eng PDFPaul.chiritaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1943 Hayek - Scientism and The Study of SocietyDocument25 pagini1943 Hayek - Scientism and The Study of SocietyJason King100% (1)

- The Whole Truth About The Ukrainian Ecclesiastical Question - Pantokratoros Monastery of Mount Athos - ENGLISHDocument21 paginiThe Whole Truth About The Ukrainian Ecclesiastical Question - Pantokratoros Monastery of Mount Athos - ENGLISHDoxologia InfonewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Chryssavgis - Remembering Archbishop Stylianos HarkianakisDocument6 paginiJohn Chryssavgis - Remembering Archbishop Stylianos HarkianakisPanagiotis AndriopoulosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taft, Robert F. Byzantine Communion Spoons: A Review of The EvidenceDocument30 paginiTaft, Robert F. Byzantine Communion Spoons: A Review of The EvidenceOleksandrVasyliev100% (1)

- Clerul Inferior in Biserica Ortodoxa - John RamseyDocument6 paginiClerul Inferior in Biserica Ortodoxa - John RamseyNiculae MarianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tales of Accidental GeniusDocument5 paginiTales of Accidental Geniuswamu885Încă nu există evaluări

- Unicode Technical Note: Byzantine Musical Notation: 1. PreliminariesDocument74 paginiUnicode Technical Note: Byzantine Musical Notation: 1. PreliminariesSebastian BuhnăÎncă nu există evaluări

- Andrei Şaguna and The Organic StatuteDocument515 paginiAndrei Şaguna and The Organic StatuteZimbrulMoldoveiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angels Depression Prayer BookDocument15 paginiAngels Depression Prayer BookTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Bitcoin Boost How To Supercharge Your Crypto GainsDocument15 paginiThe Bitcoin Boost How To Supercharge Your Crypto GainsTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- TM 807 - Eleazar Ben Judah of Worms Eser Havayot Ten EssencesDocument5 paginiTM 807 - Eleazar Ben Judah of Worms Eser Havayot Ten EssencesTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- ELazar of Worms British Library MS 27199Document3 paginiELazar of Worms British Library MS 27199TaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 13 Attributes of GodDocument9 paginiThe 13 Attributes of GodTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Three YearEnd Financial Moves To Make Right AwayDocument8 paginiThree YearEnd Financial Moves To Make Right AwayTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ephraim - Kanarfogel - German - Pietism - in - Northern France OptDocument22 paginiEphraim - Kanarfogel - German - Pietism - in - Northern France OptTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seder Olam Rabbah EngDocument54 paginiSeder Olam Rabbah EngTavi100% (1)

- The Targum To Canticles According To Six Yemen Mss Compared With The Textus Receptus PDFDocument115 paginiThe Targum To Canticles According To Six Yemen Mss Compared With The Textus Receptus PDFShlomoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas Romer Love Hebrew Bible Old TestamentDocument2 paginiThomas Romer Love Hebrew Bible Old TestamentTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nid Romania Situation R (15743438)Document3 paginiNid Romania Situation R (15743438)TaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Super Spike BlueprintDocument10 paginiThe Super Spike BlueprintTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Commission - Proposal Submission Service - User's Guide (23-03-2018)Document108 paginiEuropean Commission - Proposal Submission Service - User's Guide (23-03-2018)TaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas Romer Love Hebrew Bible Old TestamentDocument2 paginiThomas Romer Love Hebrew Bible Old TestamentTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1,001 Tips For Writers - William A. GordonDocument249 pagini1,001 Tips For Writers - William A. GordonNarwen200077% (13)

- Faith Sharing: April 16, 2006: Easter SundayDocument3 paginiFaith Sharing: April 16, 2006: Easter SundayTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bible Study - The 10 Gates of Jerusalem Book of Nehemiah Chapter 3Document7 paginiBible Study - The 10 Gates of Jerusalem Book of Nehemiah Chapter 3TaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philo of Alexandria On SleepDocument7 paginiPhilo of Alexandria On SleepTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guide To Finding AgentDocument6 paginiGuide To Finding AgentTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Askhenazi Hasidism EleazarDocument17 paginiAskhenazi Hasidism EleazarTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who Read Christian Apocrypha SBL FormatDocument16 paginiWho Read Christian Apocrypha SBL FormatTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sol 10 CommandmentsDocument1 paginăSol 10 CommandmentsTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sol 10 CommandmentsDocument1 paginăSol 10 CommandmentsTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oral Written GospelDocument5 paginiOral Written GospelTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Werner K Oral BibleDocument3 paginiWerner K Oral BibleTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angelic "Worship" of Christ in Hebrews 1 - 6 - Larry Hurtado's BlogDocument2 paginiAngelic "Worship" of Christ in Hebrews 1 - 6 - Larry Hurtado's BlogTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Christian Book CultureDocument18 paginiEarly Christian Book CultureTavi100% (1)

- How Early Are NT WritingsDocument3 paginiHow Early Are NT WritingsTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thiselton Review Ist CorinthiansDocument4 paginiThiselton Review Ist CorinthiansTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morton Smith - Cult of YhwhDocument2 paginiMorton Smith - Cult of YhwhTaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gedaliahu A. Stroumsa - Another Seed: Studies in Gnostic MythologyDocument213 paginiGedaliahu A. Stroumsa - Another Seed: Studies in Gnostic MythologyFrancesco Tabarrini100% (3)

- CLE 8 TB U1 Chapter 1 Opening Doors To ChristDocument23 paginiCLE 8 TB U1 Chapter 1 Opening Doors To Christreese marcus0% (1)

- Gnosis GnosticismDocument12 paginiGnosis GnosticismwaynefergusonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philip L. Tite The Apocryphal Epistle To The Laodiceans An Epistolary and Rhetorical Analysis 2012Document173 paginiPhilip L. Tite The Apocryphal Epistle To The Laodiceans An Epistolary and Rhetorical Analysis 2012Novi Testamenti Filius100% (1)

- Acts 8:37Document2 paginiActs 8:37Luke100% (1)

- Interpretation of The Christological Official Agreements Between The Orthodox Church and The Oriental Orthodox ChurchesDocument3 paginiInterpretation of The Christological Official Agreements Between The Orthodox Church and The Oriental Orthodox ChurchesskimnosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Church HistoryDocument58 paginiChurch HistoryLiegn RenaldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apologists 071617Document45 paginiApologists 071617Camille EscoteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Philemon: StructureDocument5 paginiIntroduction To Philemon: StructuredonjazonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DunlapgirlsopenDocument12 paginiDunlapgirlsopenapi-248185892Încă nu există evaluări

- Christianity and PaganismDocument7 paginiChristianity and PaganismtinyikoÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Much Did Early Christians Refer To The Old Testament?: - Mar. 2020 VersionDocument11 paginiHow Much Did Early Christians Refer To The Old Testament?: - Mar. 2020 VersionSteven MorrisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Not by Paul Alone - David R. NienhuisDocument279 paginiNot by Paul Alone - David R. NienhuisМарија Тодоровић100% (2)

- The Jerusalem Council The Point at IssueDocument3 paginiThe Jerusalem Council The Point at IssuereginÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apostles SummaryDocument6 paginiApostles SummaryEsquibel JustineÎncă nu există evaluări

- História Da IgrejaDocument234 paginiHistória Da IgrejaRubens Tiago GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communications ProgrammeDocument33 paginiCommunications ProgrammeIsaac SoonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apostle Peter Biography - Timeline, Life, and DeathDocument16 paginiApostle Peter Biography - Timeline, Life, and DeathVianah Eve EscobidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Albert C. Sundberg, Jr. - 'Canon Muratori' A Fourth Century ListDocument41 paginiAlbert C. Sundberg, Jr. - 'Canon Muratori' A Fourth Century ListVetusta MaiestasÎncă nu există evaluări

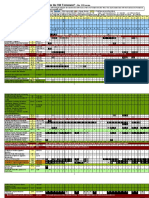

- Senior High School Forms 2019 Grade 11 STEM INNOVATIVEDocument59 paginiSenior High School Forms 2019 Grade 11 STEM INNOVATIVESeyMar DocaseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pistis Christou BibliographyDocument10 paginiPistis Christou BibliographyFrogbert100% (1)

- Survey of ActsDocument5 paginiSurvey of ActsDanny DavisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patrology Dispense EnglishDocument147 paginiPatrology Dispense EnglishAthenagoras Evangelos100% (1)

- Feldmeier 7Document23 paginiFeldmeier 7Tiaan de JagerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oskar Scarsune PDFDocument961 paginiOskar Scarsune PDFAlex Pereira100% (2)

- Robinson. Texts and Studies: Contributions To Biblical and Patristic Literature. Volume 5.Document694 paginiRobinson. Texts and Studies: Contributions To Biblical and Patristic Literature. Volume 5.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nineveh Lent - Namaskaram - Prose - W-Promiyons 1Document400 paginiNineveh Lent - Namaskaram - Prose - W-Promiyons 1Jaison JacobÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18-9 Missing ScripturesDocument2 pagini18-9 Missing ScripturesmartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gospel of ThomasDocument17 paginiGospel of Thomasdemetrios2017Încă nu există evaluări

- Anglo Saxon MissionDocument2 paginiAnglo Saxon MissionJoshua J. IsraelÎncă nu există evaluări