Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Applying Interpersonal Phycoteraphy

Încărcat de

Waleska CruzDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Applying Interpersonal Phycoteraphy

Încărcat de

Waleska CruzDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Applying Interpersonal Psychotherapy to BereavementRelated Depression Following Loss of a Spouse in Late Life

MARK CLEON BARBARA

JULIE

D.

MILLER,

M.D., M.D., M.S., L.S.W.,

M.ED.,

STANLEY

ELLEN

FRANK,

Pn.D. P

ii

.

CORNES, ANDERSON,

MALLOY,

D.

EHRENPREIS,

IMBER,

D.

LIN

REBECCA JEAN

L.S.W.

PH.D.

SILBERMAN, ZALTMAN,

LEE CHARLES

WOLFSON,

L.S.W.

F.

REYNOLDS

III,

M.D.

The efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy (1Ff) as a treat ment for outpatients with major adapted

life. applying

Grief

into

is not a disease,

one.

but

it

can develop

depression

has

been

documented

in sevhas been

-George

Engel

eral controlled The authors

trials.

report

Recently, depression

IPT

specifi cally for

in late in

on their experience

T

anxiety

he known include disorders;

consequences increased rates increased

of bereavement of depressive consumption exacerbadiminished premature suicide, disa and of

pression

their

IPT to geriatric patients whose deis temporally linked to the loss of Detailed with treatment case vignettes. techniques Prelimi-

spouses.

are illustrated

nary treatment outcomes are presented for 6 subjects who showed a mean change on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale forDepression from 18.5 2.3 SD to 7.2 4.6 after an average of 17 weekly 1Ff sessions. 1Ff appears to be an effective short-term treatin elment for bereavement-related derly subjects.

and (The Journal of Psychotherapy Research 1994; 3:149-162) Practice

alcohol, tobacco, and tranquilizers; tion of existing medical illness; immune competence; and mortality accidents, 10% noted into

Received accepted Institute Medicine, quests Clinic, Room

from increased cirrhosis, and or more

rates of cardiovascular after

ease.#{176} A year

widowhood,

to 20% rate by Clayton an annual

June November and to Dr. Clinic, Miller, of Pittsburgh, University 742 Bellefield Copyright 18,

of major depression was and Darvish, translating of 80,000

revised 1993. From November Western Address Psychiatric of Pittsburgh

incidence

1993; 22,

to 160,000

18, School reprint Institute of Medicine, PA 15213. Press, Inc. 1993; of reand

depression

Psychiatric

University Pennsylvania. Western

Pittsburgh School Towers, Pittsburgh, American Psychiatric

1994

JOURNAL

OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

PRACTICE

AND

RESEARCH

150

BEREAVEMENT

IN LATE

LIFE

cases cently, major as 24%

of bereavement-related Zisook depression at 2 months, after and Schucter2 23% their in 350 widows loss,

depression. reported and rates widowers and

Reof 16% with subdecline bewho a

major trial. The tients

depression use has of IPT been

in

a 3-year depressed

maintenance older recently using of therapies paby

it

with

at 7 months, compared

specifically

addressed

at 13 months

4% rate of depression jects whose spouses We have recently

in 126 age-matched were still living. reported a large for Depression subjects with depression

Sholomskas et al.2 and more Frank et aL,6 who are currently long-term late-life tients female maintenance depression. late trial

by in a in

in Hamilton Rating Scale (Ham-D) ratings in elderly reavement-related were treated with the tyline.34 However, showed only a small by data as measured Grief.5 These major

It should be acknowledged who lose a spouse in and that the loss often

that most palife will be in the

occurs

antidepressant these same decline in grief

nortrippatients intensity of the

context of other stressors associated with this life stage. Medical, sensory, or ambulatory disability, tirement, elements reactions financial and that strain, adjustment to reloneliness are a few of the set the stage for our patients loss.

SPECIFICITY FOR GRIEF

the Texas Inventory suggest that although symptoms may

somatic or vegetative ment-related depression treatment with such treatment psychological

of bereavebenefit from medication, change in the specifically argues to the major our efforts in

to their IPT

antidepressant makes little distress associated

with the loss of a spouse. for a psychotherapeutic management depression. This applying chotherapy spousally

This finding component

In the

second

edition

of the

classic

text

Grief

of bereavement-related report the will outline

Counseling and Grief Therapy, Worden23 outlines four tasks of mourning: 1) accept the reality of the loss; 2) work through the pain of grief; 3) adjust to an environment in which the deceased relocate the Kierman is missing; and 4) emotionally deceased and move on with life. define 1FF consistent to treat goals unresolved and

principles of interpersonal psy(IPT) to elderly, depressed, bereaved patients in a research seton our treatment IPT/LL.6 previous adof major Illustrative

et al.7

ting. These efforts draw aptation of 1FF for the depression in late life: case examples will specific techniques tion. Response data pendent raters Interpersonal will

strategies for using grief as follows: The two

sions

be provided, as well as relevant to this populaobtained through indebe presented psychotherapy7 in 5 cases. is an in-

for depresare 1) to facilitate the mourning process, and 2) to help the patient reestablish interests and relationships that can substitute for what has been

goals of the on treatment that center grief lost. The therapists major tasks are to help

terpersonally focused, proach to the treatment It has been established

present-oriented apof affective disorder. as an effective acute, strategy with Itwas developed would today be

patients

continuation, and maintenance unipolar depressed patients. by Kierman et al.7 as what

considered a continuation therapy. Subsequently, two large trials8.9 have demonstrated its efficacy as an acute treatment, and Frank et al.2#{176} have now shown IFFs prophylactic efficacy in preventing recurrence of

assess the significance of the loss realistically and emancipate themselves from a crippling attachment to the dead person, thus becoming free to cultivate new interests and form satisfying new relationships. The therapist adopts and utilizes strategies and techniques that help the patient bring into focus memories of the lost person and emotions related to the patients experiences with the lost person. (pp. 97-98)

VOLUMES

#{149}

NUMBER

#{149}

SPRING

1994

MILLER

ETI4L.

151

GRIEF PROBLEM

AS AREA

Focus

IN

IPT educated illness, the of the probexpects to interpersonal invenof earlier of curmay fathe the to ena patient down:

date Was fering? 6. What With

the spouses illness the death a welcomed was the the 1FF history therapist

prior to death? end to sufmarriage? a

Once about next lem focus, inventory.

the the step area

1FF nature

patient

has

been

of their

of depressive regardless the therapist of the interpersonal

recognizing

in treatment, on which completion A thorough

tendency to idealize a lost mate, specific questions will allow for useful inferences. How were decisions shared? Were and there diffiresponsibilities cult times any periods marriage?

is the

tory is essential relationships rent cilitate process interpersonal following with sure relationships

to assess the quality as well as the availability and supports that

in the marriage? Were there of separation during the Was the marriage, in fact, a patient experithat, through finally ended? discussions

the last phase (reintegration). inventory, series of bereaved

of the mourning In addition to we older have to found be

severe burden? Does the ence relief on some level death, 7. Were the there relationship contingency

questions

helpful

spousally a complete

patients

understanding or of points where stuck or bogged the

of potential

with the spouse in the event that one or another partner died first? Were wills jointly? ment? with port and other legal matters handled Were there Were money plans in place the remaining areas of disagreematters discussed, to adequately suppartner? Were futhey had roman-

areas of conflict may have become

1.How much support did provide in social matters? ters 2. such as paying bills? How much adjustment manage the patients without home his or her be sold? Will

deceased Practical

mat-

is required to current lifestyle spouse? income Must drop? a

neral plans implemented 8. How thoughts frequently

discussed? Were as agreed? has Had the this patient about beginning with patient

a new possibility

tic relationship? ever been discussed spouse? Does the riod other riage of waiting

3. What proportion pendent versus have hobbies in place that support system,

of activity was indejoint? Did the patient or independent activities will provide a ready-made or did the couple A do

the patients feel that a peWere there marruminaliving? and

is proper?

relationships during the that are producing guilty the there patients children

virtually everything together? 4. What was the manner of death? chronic justment illness than

tions now? 9. Where are What ships? how clear reis the Are

allows more time for adan acute illness or accidifficulty or accepting that obviously the

quality

of those grandchildren,

relation-

dent. Was there acknowledging spouse quires 5. If the much tient cial

often is contact made? The nufamily has become widely disto may

was dying? Suicide extensive exploration.

persed, with children moving away find jobs. Thus, although children

spouse had a chronic illness, how caregiving burden did the pashoulder? burden from Was there a great care? finanDo 10. medical

mean well, their practical availability may be an issue. Have there been discussions about moving closer to children? What other losses what sources has were the of support patient susreacare available? What other tained, and

many large bills remain to be paid? What changes in the patients customary lifestyle were required to accommo-

his or her

JOURNAL

OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

PRACTICE

AND

RESEARCH

152

BEREAVEMENT

IN

LATE

LIFE

tions tion life,

to those is focused with early

losses? on any parental

Particular losses loss risk for

attenin early clearly assodepres-

EXPLORING QUALITY

MARITAL

ciated with increased sion in adulthood.24 11. Has the surviving dispose of personal ceased, perience powerful true particularly

To expand 1FF therapist

further must

on the realize

marital that the

history, quality

the of

spouse items

been able to of the deIn our ex-

the marriage has been process of bereavement. found marriages older These that bereaved more persons, authors older positively suggesting further

shown to affect the Futterman et al.27 persons than an noted rated nonbereaved idealizing bias. that bereaved their mardepressed postulates attachtheir

clothing?

in our pilot study, this act is a metaphor; it is indicative of or, if the process is probedfor also these to to letallows be

movement

tracted, of fixation. Leaving the room just as it was is common parents seen with therapists lines clues of a lost child but can The along indirect struggle loss of a spouse. direct inquiry valuable patients

depressed older patients riages more positively older that patients Bowlbys25 the quality who were attachment

viewed than did not theory parental

bereaved.

of early-life

can provide about the

ments sets the stage for all future affectional bonding. Secure attachments in early life promote that a positive self-image and other satisfying affectional In contrast, impaired the realization bonding attachments ambivcan is

hold on at all costs ting go in a measured for emotional Some patients from their 1FF ing that deceased Parker

growth.

as opposed way that

possible.

may benefit, however, therapists acknowledgattachment to the

in early life (resulting from neglectful, alent, indifferent, or abusive parenting)

a timeless

(as described by Bowlby and et al.) may be best for them. therapists should not be to paall patients on. Many

lead to lifelong difficulty in forming satisfying interpersonal relationships. Therefore, according to attachment theory, an individuals choice of mate obtainable in roots traceable and the degree of satisfaction the marital relationship have to the quality of affectional outlines the critical

Bereavement

trapped into expecting get over it and move tients, years particularly or older), where their the may

old-old (80 be at a stage in for them to and draw

bonding in early life. Erikson28 similarly

their lives consolidate

it is best memories

on them for sustenance their remaining years. 12. If patients have difficulty touch with their feelings, sidered writing a farewell deceased? encourage Leick and extensive

throughout getting in have they conletter to the Al-

importance of early relationships in the initial two stages of his development model: basic trust, as versus mistrust (engendering hope), and autonomy, as versus shame and doubt (engendering of grief therapy Davidsen-Nielsen2 tients tended who had to have will). In their 15 years experience, Leick and have noted that those padifficulty with more protracted attachments grief reacto say goodbye as well as to of a supportive the liter-

Davidsen-Nielsen2 letter writing.

though homework is not a focus of 1FF in general, we have found that its use is justified because it helps patients reach deeper levels of feeling and promotes progress. Similarly, reviewing photographs provide further els of feeling. or other stimulus memorabilia to deepen may lev-

tions. It was harder for them and to welcome new contacts make use of the healing power network. Parker ature patients ing they et al.26 recently

reviewed

that examines perceptions received and

the links of the quality their social

between of parentbonds in

VOLUME

#{149}

NUMBER

#{149}

SPRING

1994

MILLER

ETJ4L.

153

adulthood (the concept of continuity). Parker et al. point out that exceptions exist that ity run theory; is counter for to expectations example, adversity of continuin child-

toward the deceased, God, tions may be intolerable may be beyond the When the preciation the

or fate; these to admit and reached feelings and the

emothus an apfrom in a

patients

awareness.

hood impaired satisfying negative attachment

not always associated with an ability in adulthood to form stable, relationships. bias can is made that need have be That is, a pervasive corrected if a secure point in life. It forms a link with grief to recognize that the played the role of cor-

1FF therapist has of these common inventory

interpersonal

patients

own understanding of his or her difficulty dealing with the spouses death, the therapist will ask if the greater patient agrees of the to work toward understanding underpinnings

at a later

is this last point work: therapists lost spouse may recting exists 1.

of the continued grief ing obtained permission therapist to educate will often need the patient

and depression. Havto focus on grief, the to make some about common effort patmay relamixed

that pervasive negative bias. Parker et al.26 report that ample evidence to conclude Negative pose people adulthood by shaping that bonding social either models. in likely may bonding directly disin or

terns of adjustment remind the patient tionships are

to loss. The therapist that all significant by some

parent-child to judge negatively, mental

characterized

feelings and that the agreed-upon learn as much as possible about those mixed itive aspects. feelings-negative Careful empathic

task is to both sides of as well review as posof the

2.

Those early

who had extreme deficits parental care appear more an uncaring is established associated

to associate with (if a relationship 3. Initial vulnerability

partner at all). with less

events surrounding the death and the subsequent necessary adjustments will provide an invitation to renew the unfinished mourning process in a safe environment. make have 1FF their references to how become since their therapist difficulty the attempts and encourto When patients difficult their lives spouses empathize the ages lems therapist died, with the

extreme difficulties care apparently can later mate relational partners et al. latent, and

in early parental be modified by with intisignificant others. about loss reactivatself-images or compen-

experiences

Horowitz related concept ing previously that had been

have

written

them to talk about that arose in response might

personal probto their loss. The

of a profound negative

counterbalanced

all the difficulties your loss, I wonder unfair to you responsibilities? that

say, Having just heard about youve had adjusting to if it sometimes seems you The now have therapist all these extra might further

sated for by the living spouse. Patients with histories of deficient early parenting should be seen as being at greater risk for the establishment of a dysfunctional marriage or for who experiencing recting spouse had adequate

MANAGING

AMBIVALENT

the loss of the negative-bias-cormore acutely than those parenting.

NEGATIVE

EMOTIONS

say, In my experience, its not uncommon for people to feel some annoyance or anger toward the deceased as the negative part of those mixed feelings we talked about Similarly, Leick and Davidsen-Nielsen2 the invitation, patiently the With ...and listening what to earlier. use miss? positive

dont you

all the

OR

after attributes ceased.

survivor ascribes gentle persistence,

to the dethe 1FF ther-

A common of the anger,

reason

for

inhibited

completion

mourning or rage

process is ambivalence, (often at being left behind)

apist will clarify, interpret, and sometimes confront the patient with the evidence already assembled from the patients verbaliza-

JOURNAL

OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

PRACTICE

AND RESEARCH

154

BEREAVEMENT

IN LATE

LIFE

tions these

to suggest that further lines is indicated, at

inquiry the same

along time

fore

ing

educating him or her about common feelings many people harbor in the grief process. This approach mizes ate the under provides state the current reassurance feelings circumstances. and legitiThe after hope use through a in the of mixed as appropri-

his death. She described a mutually satisfysex life and said that both were dismayed about recent difficulties. She was very careful to downplay the loss of erectile function (and of missing her own sexual pleasure) to avoid making him feel insecure. They had discussed the possibility of getting it checked medically but had never done so. The patient described considerable unburdening relief at the opportunity

experience of relief or unburdening session along these lines often instills the the patient grief and that expertise the he to or she help can get therapists

accompanying

depression.

Coming to Terms With Ambivalent or Affect. Mrs. H. was referred because of uncontrollable crying spells and inability to concentrate at work. Her husband had died suddenly of a heart attack 6 months earlier. She had been previously divorced and had enjoyed her second marriage for 12 years. She spent the first sessions talking about her embarrassment at being unable to control her emotions and how much she had enjoyed her lost love, especially compared with her first husband. The first task of therapy was to give her permission to grieve, to allow herself to feel whatever was there at the moment. Some time was also spent in early sessions on practical matters such as encouraging her to respectfully decline invitations she was not up to and realistically appraising alternative ways to better handle her emotional outbursts at work. After several sessions of idealizing the patients dead husband, the question Where is the ambivalence? arose in the mind of the therapist. Why is this patient unable to move forward? Gradually, a theme began to emerge concerning her husbands unwillingness to get adequate medical examinations. She felt that if she had been successful maybe his death could have been prevented. She admitted feeling enraged at the thought that he might have concealed knowledge of medical illness with which he did not want to burden her. Finally, she also came to acknowledge angry feelings that he might still be here (for her) if he had heeded her advice to get medical evaluation. These thoughts were quickly followed by guilty ruminaNegative tions for thinking so selfishly. was a decline in A parallel development

Case!:

to discuss these issues in detail, particularly her guilty ruminations about having selfishly encouraged medical evaluation for a sexual problem when, in retrospect, he really needed medical help to save his life. Out of respect for her dead husband she had been unable to discuss all these ramifications with well-meaning friends and family. Mrs. H. progressed, with continual clarification and confrontation of these themes, to the point of accepting plans to travel with family, and she got through the death anniversary with less stress than expected. She was no longer crying at work nor thinking constantly about her late husband, and she agreed that it was time to terminate treatment. Comment: example reaved sessions. from find common rence, presence tions, then a therapeutic cating the is well within Although alent authors sal, and overzealous Case or This case idealizing patients posture vignette is a good

of the depressed It is this the negative painful to job

posture that bebring to the initial that protects affects The understand them they IPT this

or ambivalent acknowledge.

first,

therapists

is,

to

phenomenon, and look for from the

anticipate its occurevidence to support its patients own verbaliza-

to reflect it back to the patient in manner, at the same time edupatient that his or her experience the range of the normal. conflict over expressing affect is common it is by no means are cautioned along these ambivin the univeragainst lines.

negative experience, 1FF therapists

interpretations

her

husbands

sexual

potency

in the months

be-

2: Struggling to Do the Right Thing. Mr. a construction worker, presented with a 30pound weight loss, anergia, anhedonia, and passive suicidal ideation. He reported severe grief reactions after his mother, father, and father-in-

VOLUME

#{149}

NUMBER

#{149}

SPRING

1994

MILLER

ETAL.

155

law died.

my best lingering

He described

friend, death lover, after required care. he death. his her time grave

his

and many her

wife wife. years

of 43 She of

years had illness,

as died the a

ing as

new if any

relationships progress Mr. G., torn relationships his defenses

can would

be truly be

paralyzing, the

betraying

last 4 of which with to 76 24-hour pounds, her

to be bedridden her decline himself he praying, had in weight to anbeen and

deceased. ing new showed

by conflict over formsince his wifes death, in his flirtatiousness and left him exhim to deal conflict and to relocate and begin

Despite had Since attending daily. not

allowed her death, Mass,

ticipate spending visiting

his immersion in activities that hausted. His 1FF therapist helped with both sides of this underlying

his

The

sions ate When was

most

sexual

striking

with

aspect

of his and staff

early inapproprimembers.

ses-

preoccupation female with

to work through deceased

it, enabling wife emotionally

him

flirtatiousness

dating.

a INCOMPLFTE MOURNING

finally confronted

the interpretation must be hiding and

that his overzealous great discussed ionship; about outside deal of pain, how however, Catholic much he religious

advances Mr. he felt

G. became missed greatly

tearful female conflicted

compan-

prohibitions

After this

against He was

sex

Grief work reactivated ing vignette

can reach by subsequent illustrates.

Mourning.

a plateau, events.

only to be The follow-

of marriage.

confrontation,

his flirting

painfully

toned

aware of

down

his

considerably.

loneliness and

emptiness.

He said he wouldnt

of but 43 lence that doubted didnt ing up want with to and Mr. hobbies necessary would find he his he years. about missed that to he hurt system felt He until awkward talked forming his

be able

another because at length new wifes

to get his wife out

woman he had came not his along, dated ambivasaying and her. he dated He in

Case 3: Incomplete wife in a 2-year battle

immediately tive for duty 6 months in after the Persian until

Mr.

P. lost

his

her

with breast cancer. Almost death, he was called to acGulf, where he served

reached the mandatory re-

about relationships,

he

tirement and he after woman His poor themes had now his

openness replace

trust

said by breakdescribed

age.

wifes 17 years initial

He became

death his when junior.

depressed

he began

14.months

dating a

could

anyone but he

complaints and

were preoccupation example,

poor

sleep, with

them, a new count G. described

alternatively he

motivation, of death-for outlived bypass

a wish down

relationship on. a parallel activities, a level of which

could

nail

feeling guarantee friends who in

that on also the from

he his had previany this

the surgery

10-year (two

overactivity he said that was

in

cardiac undergone ous

and to allow After

sport reach him his away

bypass He because

surgery did he not felt

had want he

died help had to

exhaustion

6 months).

to sleep

at night. he wifes his had his reported reminders house first in date a and that

medication

do

eighth some

session, of his

himself.

Mr. ing fun P. described with his new feeling lady friend, guilty about feeling havthat it

he and more talked

had had

put

begun

redecorating decor. He

manly

of his struggle with the realization that experience was bound to be new and different. He continued his ambivalent struggle with sexual activity. Mr. G. reported on his progress in therapy, saying: Ive come through some bad months; I never thought Id make it. He described reducing his cemetery visits to once a his week, has upon joined dating a square dance group, and

wasnt fair that it couldnt knowledged that he had

nity to grieve for his

now unfair to burden grief. He was obsessed

might wifes mistakenly name. refer

be his wife. He acnever had the opportulate wife and felt that it was his new friend with his

with to his the new thought friend that he by his

Mr. P. felt that

and that he had been

he had

there

a good

marriage

for his wife

looks

as a challenge.

rightly shame

Comment: Leick and Davidsen-Nielsen2 point out that feelings of guilt and that follow steps of progress in form-

throughout her decline and death. He expressed gratitude for the opportunity to discuss his feelings and reported feeling and sleeping better after several sessions. A tragic coincidence occurred during the

JOURNAL

OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

PRACTICE

AND RESEARCH

156

BEREAVEMENT

IN LATE

LIFE

his mother was diagnosed with breast cancer and was near death on the 2-year anniversary of his wifes death. Upon exploration, Mr. P. did not feel that he had a good relationship with his mother, summing his feelings for her as respect for raising her kids alone. As his mothers condition deteriorated he was able to make time for her without resentment or guilt feelings. therapy: After his mothers death, Mr. P. dealt with

feelings however,

about

the the

death case

is clearly that role

required; transitions

it is also

are often dictated after the death

conflicts may

by changing of a spouse;

exacerbate

circumstances interpersonal

family

remaining

relationships; and strongly influence through cases Case

died brought

interpersonal the way process. problem

deficits a patient The areas.

may goes

the illustrate 4: Role

4 months to

grieving these Transitions.

earlier of by

following

her estate and felt satisfaction in his ability to be there for her even though his mother had not been there for him during his wifes battle with cancer. He was able to find satisfaction in the knowledge that he attended without reservation to his mother as well as his wife on their deathbeds.

Mrs. P.s husband

liver her cancer. adult She children was

had

with

treatment

Comment: was to provide restart the his military his new solved tionally

The a safe mourning service.

first

task

of 1FF with in which

Mr. P.

forum

he could

process interrupted by The inhibition he felt in was not going to be reof emohe could

relationship

whom she had been living sequentially, exhausting and frustrating each one in turn. They described her as weepy, clinging, and unwilling to be left alone even for short periods. In private, her children described their late father as an abusive alcoholic, and they collectively expressed their amazement that their mother had stayed with him. At the initial evaluation, the patient was severely depressed and required 3 weeks of hospitalization that included

treatment with antidepressant medication. The

until he finished the process relocating his wife to a place

hospitalization

brought

considerable

relief

to

accept. His 1FF therapist was able to allow him to explore all the feelings he was experiencing without the unfair burdening of his new friend. His mothers illness caused him to review as well realistically as revisit his relationship his role as caregiver with for her both

the children, who were very willing portive but had been overwhelmed

pendency When needs. the psychotherapy resumed

to be supby her deon an

outpatient basis, Mrs. P. expressed

tendance at her home by grown and

the greatest was for the

children her loss

feeling

past at Sunday

of loss that

obligatory dinners hub at-

his mother and his wife. Ultimately, Mr. P. was able to acknowledge that he had been there for them both and could now let them rest and move on to new relationships. Leick and Davidsen-Nielsen2 describe the readiness to love again as being prepared to live through the grief

OTHER

of status

as the

of a new

loss.

AREAS

PROBLEM

of family activity. It was as if she were willing to overlook or tolerate her husbands abusiveness as long as she could counterbalance it with satisfaction from the maternal role, in which everyone came home to her. One daughter, in particular, revealed her own struggles in her psychotherapy and Children of Alcoholics support groups to break from what she termed an enmeshed, dysfunctional family. Therapy with this patient was clearly focused spent on role transition. the Many differences sessions between were her exploring

Although four problem experience

grief

is the

most

common

of

the

areas that we focused with bereaved older

on in our persons,

each of the other three 1FF problem areas (role transition, interpersonal conflict, and interpersonal deficits) has come to bear on the management tion of the patients of grief reactions. Exploraimmediate reactions and

wishes and more realistic expectations concerning her grown childrens aspirations and their allegiance to her. She was gently challenged to take more responsibility for her own needs and to learn better ways to cope with their independent activities. She somewhat idealized her late husband but referred far less often to him than

VOLUME

#{149} NUMBER

#{149}

SPRING

1994

MILLER

ETAL.

157

to

the

loss After

of her 3 months an

previous

lifestyle. progress, and needs Mrs. successover a wider P.

to felt

the forefront.

doing things

She described

alone rather

how strange

than as a couple.

it

of steady building

moved fully

to spread

apartment her dependency

area

by looking and

in on other joining a local

widows senior

in her center,

building where she Her family portive

comfortable.

For example, now she had to park the car herself, initiate social contacts, and go alone to the country club socials they had attended so often together. She referred to a list she was keeping

of these alone firsts. Mrs. T. was acutely aware

served food continued with

to less able members. to be involved and supwhich they were more

at a level

Comment: patients with were heavily

As

the

above dependent in the

case

illustrates,

traits

strong invested

support

who their

spouses provided will have a much more difficult time adjusting to the loss and establishing new roles for themselves. Traits of excessive terpersonal

Case

Mrs. week 12 have

dependency conflict Time

died presented during 50th

can among for

also

precipitate members.

in-

family

of missing the hundreds of daily physical touches from her mate, not the least of which was sleeping together. Not all of her changed roles were unpleasant, however. She realized, for example, that she no longer had to be one of the first to leave parties as her husband had always demanded. She could now make decisions with only one set of preferences to consider. Mrs. T. s social network was extensive, and she was able to draw on it for considerable support. For example, she organized a slumber party with a cohort of grade school friends who

had kept that friends up the with party return each had to other. to their end The the pangs next of reday lives and gret

5: No More

T.s husband illness. months marked She later, her

Experimentation. following for that anniversary. therapy would a one-

suddenly herself the wedding month

her

individual

portended

termination. style defensive to

similar

Her a more posture

difficulties

therapist protective short-lived,

with approaching

noted a change stance. however, in This and

isolated, was

Mrs. T. described

somehow band able was to her. she sick, She should even

feeling

have though known no

guilty

that clues that

because

her were her husavail-

Mrs. T. was able

has shown

to terminate

successfully

and

capability.

considerable

independent

acknowledged

marriage

Upon her and describe always bulk

was

further

not

her

great

husband

in the

her

later

years.

heard negative,

exploration,

therapist

Comment: Mrs. T. clearly felt husbands death was untimely. He died a short prefer), experiment illness, and of he he died first in the her (as he said died changing life and part midst of approach quite

her after hed her toingreat Mrs. T.

as crabby,

angry.

moods so her in

the

cult

of their

Mrs. T. described marriage tolerating

but found years. the to one though now her felt later from was even She toward She

spending her

diffidescribed

husbands to do

it increasingly

the style

changing soother as crabby of character she

accommodating who became it seemed guilty, just out as if her had reconcon-

ward volved changes

him. Their socially, on her

together was this required after his death.

usually was, her.

as he for in behavior

change

husband

been

without sider. versations preference feelings

an experiment

giving On another with that toward her he him her any

that

theme, husband go for

ended

Mrs. T. about and

disastrously

to recalled his admitted willing

felt the loss of proximity to her husband even more profoundly. In 1FF she was able to explore all these issues and was able to use the resource of her social network to help fill the void she felt. Predictably, value the relationship with she quickly came her 1FF therapist, to

opportunity

first

angry

it to

successfully

happen.

After to express much she Mrs. her missed T. had his had feelings company, ample her opportunity as well as how to attempts negative

and the prospect of termination was, at first, a difficult one. The feelings of need that arose in the context of termination were taken up and worked through over several this sessions, transition emphasize and Mrs. successfully Leick T. was able to make as well. and Davidsen-Nielsen2

grapple

with

the role

changes

in her life came

JOURNAL

OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

PRACTICE

AND RESEARCH

158

BEREAVEMENT

IN

LATE

LIFE

that

learning

new

skills

is a prominent in the emotion

comcase can

tients

with

a primary

focus

on role

transition fol-

ponent of Mrs. also with new

of grief work, as illustrated T. Talking about intense

or interpersonal lowing 1. From our specific From range

conflict. experience, techniques we suggest the for termination:

be a new skill, the experience Using skill the for social the

especially when of unburdening network bereaved. can

coupled relief. be a and not with you to you

also Leick Can

the beginning, of the anticipated

clearly state the length of ther-

Davidsen-Nielsen2 suggest ask your friend/confidant try while

your

asking, (network) just you rather to feel, be

apy, generally quent reminders date 2.

16-20 weeks, with freof the approaching of a temnear is, make as

to

comfort you

tears?

you about like

but how

of termination.

talk

to tolerate than half now funca

Feeling

a self

Frankly discuss the possibility porary resurgence of symptoms the time of termination; that full well use on of an educational one. alternative as specific exploring (such as a therapeutic

dyad is another by Mrs. T. when decide tions.

TERMINATION

required skill demonstrated she realized she could when to leave social

approach coping plans

for

herself

3.

Focus strategies

to com-

ISSUES GRIEF WORK

IN

IPT In Interpersonal

bat loneliness). Begin well ahead of termination to allow some experimentation on the patients part, with review and possible subsequent Encourage Except for revision of those sessions. new relationships. patients who remain plans in

Psychotherapy

of Depression,

4.

Klerman et al.7 suggest the following in the final three or four sessions to facilitate the termination process: 1) explicit discussion of the end of treatment; 2) acknowledgment of the end grieving; of treatment and 3) as a time movement or to of potential toward the her indepenfor must

severely of

symptomatic, Klerman et telling patients who report discomfort with the prospect

al.7 recommend a high level of termination

patients recognition of his dent competence. For patients who come help with spousal loss, the

therapy

1FF

therapist

that a minimum 4- to 8-week waiting period is required before beginning further treatment of a different type. This conveys a clear message that this therapy will be completed, that ability

before

pay careful attention to the possibility that the patient will experience the termination of the psychotherapy as an additional loss. Much has been written about termination in shortterm therapies in longer term elapsed velop. during Furthermore, the also being easier to negotiate than therapy because less time has which dependency can in 1FF, transference dein-

the

therapist to function

further

is confidant outside

treatment

of the of therapy, is started

patients and that the patrial psychodetail on

tient

should

first

make issues

a reasonable in short-term in further

his or her own. Termination therapy by other have been authors.3032

discussed

terpretations to keep significant (which

are specifically avoided in order patients conflicts focused on figures serves in their everyday dependence 1FF difficulty became than for therawith depaWe conducted lives to discourage

PRELIMINARY

RESPONSE DATA

on the therapist). Nevertheless, pists should anticipate greater termination pressed in the for patients who of a loss context

a preliminary

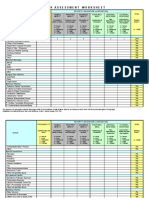

study of depressed In the study, age 68

of

1FF

efficacy reaved and

in the treatment spouses in late life. patients,

be3 male (range

3 female

mean

VOLUME

#{149}

NUMBER

#{149}

SPRING

1994

MIILER

ETAL.

159

64-73) Research minor ment after 69.2 an the

were

engaged

in 1FF Criteria Subjects

after

meeting

offer

key

elements

common

to all grief

ther-

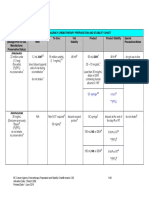

Diagnostic depression. average loss of their

for major or entered treat(range Mean had been 11-56) age married IndeHam-D Assesswas

apies. These are defined by Raphael in her excellent review as 1) establishing a relationship with the bereaved, the 2) exploring the loss, 3) reviewing ing background and and have 6) achieving Behavioral brief been lost relationship, issues, 5) providing goals therapy, (recovery). cognitive for 4) explorsupport, therapy, of the

of 26 weeks spouses. subjects

6.0 SD, and

an average pendent scores

of 42 years raters obtained 2.3/7.2

(range 25-49). pre/post 4.6; Global

of 18.5

ment Scale33 scores of 62.5 and Texas Revised Inventory of 49.3 9.6/39.2 14.9 after data weekly 1FF sessions. These preliminary is an effective treatment related depression rently comparing nortriptyline, and

4.3/78.39; of Grief scores a mean suggest that of 17 1FF

relational/insight compared in older to bereavement).

psychotherapy the treatment (not necessarily of showed cognitive Results

depression secondary study

a

persons

by Gallagher slightly better

and Thompson35 outcome for the groups than group, although than that dropout clear. a focus

for

bereavementWe are curof IPT, therapy in double-

in the elderly. the efficacy combination randomized conditions.

0 N

and behavioral tional/insight bers and comparisons Thompson

for the small rates make Gallagher on goals

relanumthe and

differential less argue

this population under blind placebo-controlled D Interpersonal designed depression,

grief, role

as well

as skill training is essential therapies for depression. oped strongly specifically for areas:

conflict,

to effective psychoAlthough 1FF develmodel, focused homework in 1FF, to improve the pursuit on it is interand

I S C U S S I

out

of the goal themes. not

psychodynamic Specific employed to consider

oriented

psychotherapy as a short-term focusing

transition,

was four

psychotherapy on major foci

interpersonal

personal ments patients nication

are

assignalthough commuof ef-

are

encouraged

skills,

and and

of

interpersonal role transition bereaved may become also setting.

interpersonal

deficit. The are particularly depressed

conflict

of grief germane The in the foci beand

fective coping strategies, and implications of such changes therapy sessions. al. undertook and process Horowitz et study of dispositional

to discuss the at subsequent a detailed variables in psychodyfrom this

to the deficits reavement may patients degrees greater

patient.

and

interpersonal

require

attention by the

Surviving

relationships loss,

unbalanced

52 bereaved patients namic psychotherapy. complex of 1FF.

treated with A few points

with interpersonal deficits (greater of character pathology) may be at risk for inhibited or prolonged grief. it it be

study merit mention Horowitz et al. found

in the context that even pa-

1FF focuses on interpersonal themes, incorporates an educational approach, and can be used medication. taught sionals workers, tical in conjunction The principles of mental with psychotropic of 1FF can health professocial it a prac-

tients ordinarily poor candidates low motivation could still be active, supportive motivation had

considered to be relatively for brief therapy because of or low developmental level engaged in treatment by an therapist. Patients with low better outcomes regarding with highly highly motiwhen when matched Conversely, better

to a variety (psychiatrists, psychiatric treatment for

psychologists, nurses), making bereavement-related

termination issues active therapists. vated patients had

de-

outcomes

pression. When comparing pies for bereavement,

1FF with other thera1FF does appear to

their therapists took a less active stance in the termination phase. In general, however, Horowitz et al. found that more exploratory

JOURNAL

OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

PRACTICE

AND

RESEARCH

160

BEREAVEMENT

IN LATE

LIFE

actions

by

the

therapist

worked

best

for

mailed may help

solicitation,

however,

and

this method subgroup. mutual selfdynamic psysessions psychowith the late Al-

highly motivated less well for less

or organized motivated or actions with

patients and less organized were indicated active and

have selected a help-seeking Marmar et al.4#{176} compared group therapy with brief weekly individual psychodynamic on conflicts impede

patients. Supportive for the latter group. 1FF is consistent supportive commodate therapist both

both

chotherapy (12 with experienced therapists, spouse that though both in symptoms Marmar participants individual Mutual focused might

approaches high and low

and can aclevels of pa-

mourning). reduction and anxiety, dropout compared provide rate

tient motivation and to establish a positive and to agree therapist to a focus of the

organization. 1FF seeks working alliance quickly early on. The attitude and educating,

groups experienced of depression a larger therapy groups of group

et al. found therapy. self-help

in

is supportive, capable exploration

with consen-

active. Those patients for more in-depth aged by however, exploratory

of or motivated are encourto undertake patients with benefit from stance and however, it, less the

the 1FF therapist in our experience,

desire can

still

sual validation, a forum to express difficult affects, peer support, and facilitation of problem solving. These groups are beneficial to many widows and widowers, particularly or help-seeking with less severe severe depresdiffithose with interpersonal depression. sion, culties, more more outgoing styles or those Those with more complicated

supportive, educational, active 1FF therapist. Psychodynamic psychotherapy have common historical transference of roots; early a focus difference of

allows

of the 1FF 1FF or

discourages

interpretations life experion interperperhaps 1FF

interpersonal

extensive exploration ences while encouraging sonal themes. This decreases termination effectively Group

studied

or a reluctance to join a group may require a more tailored individual psychotherapeutic approach.4#{176} ual Given the differences depth among and breadth of individwidows and widowers, apto

the

intensity issues and

patient-therapist to be used

by less experienced therapists. therapy for the bereaved has been authors.372Vachon et al.,37 assigned widows randomly to a

or an intervention group

by several group

for

example,

it is not surprising that a variety of approaches are potentially beneficial. 1FF is one proach that can provide a workable forum address systematically bereavement-related depression of mental The authors and health that can be taught practitioners.

control

to a variety

(widow-to-widow the intervention tional deterioration

control group after

program) group that the

and

found

that

resisted the emowas noted in the

support

thank

Donna

M. Ulrich for her tech-

postbereavement

nical assistance.

had Work wassupportedfryNationallnstiMeofMental Health Grants MH43832, MJ-100295, M1-13 7869 (C.FR Ill), MH30915 (Dr. D.j Kupfer), and a NationalAllianceforResearch on Schizophrenia and Depression a (NARSAD) Young InvestigatorAward

waned. caught months, ahead larly,

comparing

Even

though

control

group group was

up to the intervention the intervention group in the Lieberman

at 12 clearly Simi,

resocialization process. and Videka-Sherman

group participants

self-help

and that and

(M.D.M.).

This paper was presented

normative sample the interventions that improvement for simply by the both of these

of widows, were truly could passage studies

concluded therapeutic

in part at the Confer

not be accounted of time. Subjects were recruited by

in a

ence of the International Psychogeriatric Association, Berlin, Germany, September 1993, and at the NAPSAD Annual Symposium, New York City, October

1993.

VOLUME

#{149}

NUMBER

#{149}

SPRING

1994

MILLER

ETAL.

161

1. Zisook

S (ed):

Biopsychosocial

Aspects Series, Press, M: Healing London MulIis Nursing MR:

of

Bereave-

18. Elkin rative

I, Shea Research

MT,

WatkinsJT, Treatment Program:

et al: National of Depression General 1982; Prusoff year

Institute Collaboof

ment (Progress in Psychiatry ton, DC, American Psychiatric 2. Leick ment, 3. Valanis among Journal 4. Calabrese N, Davidsen-Nielsen loss, and grief therapy. 1991 RC, and Kling MA, B, Yeaworth

vol 8). Washing1987 pain: attachand New York, Alcohol older persons. 13:26-32 in imand Am use

of Mental treatments. 19. Weissman pressed with Arch 20. Frank comes pression. Gen drugs

Health

effectiveness

Arch Gen Psychiatry MM, Klerman GL, outpatients: and/or Psychiatry results one interpersonal

46:971-982 BA, et al: Deafter treatment psychotherapy. outde-

Tavistock/Routledge, bereaved JE,

nonbereaved Gold PW:

1981; 38:51-55 PerelJM, et al: Three-year therapies in recurrent Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093-1099

of Gerontological

1987;

Alteration bereavement, regulation. RO

E, Kupfer DJ, for maintenance Arch Gen

munocompetence depression: focus

during stress, of neuroendocrine

J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1123-1134 5. Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hanson

book vention. Press, 6. Gallagher of Bereavement Cambridge, 1993 DE, Thompson LW, Theory, England,

21. SholomskasAJ, term interpersonal elderly: 1983; case 37:552-566

Chevron ES, Prusoff BA, et al: Shorttherapy (IVT) with the depressed and discussion. AmJ et Psychother

(eds): Handand InterUniversity Psychoso-

reports Frank

Research Cambridge PetersonjA:

22. Reynolds CF, pharmacotherapy and continuation recurrent major AmJ Psychiatry 23. WordenJW: Handbook edition. New

and

E, Perel JM, psychotherapy

al: Combined in the acute patients with report. A 2nd

treatment

of elderly

cial factors affecting adaptation the elderly. IntJ Aging Hum Dcv 7. ParkesCM, Benjamin B, Fitzgerald a statistical study of increased owers. British MedicalJournal 8. Parkes for the

Psychiatric

to bereavement in 1981-82; 14:79-95 RG: Broken heart: wid-

depression: a preliminary 1992; 149:1687-1692 and Health 1991

mortality among 1969; 1:740-743 implications of pathologic

Grief Counseling for the Mental York, Springer,

Grief Therapy: Practitioner,

CM:

Risk

Annals

factors and 1990; Annals

in bereavement: treatment 20:308-313 complications 1990; 20:314-317

prevention Kim Psychiatric S. Ostfeld of

grief.

9.JacobsS, ment. 10.Jacobs mortality 39:344-357 11. Clayton toms and Mental

K: Psychiatric

of bereavereview Med of the 1977; sympin Stress New the York, first 1991;

24. Lloyd C: Life events and depressive disorders reviewed. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:529-535 25. Bowlby J: The making and breaking of affectional bonds. BrJ Psychiatry 1977; 130:201-209 26. Parker GB, Barrett EA, Hickie IB: From nurture to

network: parenting adulthood. 27. Futterman spective depression examining received AmJ links Psychiatry of between and 1992; perceptions social bonds of in in childhood

A: An epidemiological bereavement. JS: Course stress edited Psychosom

149:877-885

Retroand

PJ, Darvish the Disorder,

of depressive by BarrettJE.

following

of bereavement,

A, Gallagher assessment

D, Thompson LW: marital adjustment

Raven, 1979, pp 121-1 36 12. Zisook 5, Schucter SR Depression through year after the death ofa spouse. AmJ Psychiatry 148:1346-1352 13. Pasternak RE, Acute open-trial ment-related Reynolds depression Development illness. CF, Schlernitzauer therapy life.J of British Clin of

during the first 2 years of spousal bereavement. Pathology and Aging 1990; 5:277-283 28. Erikson EH: Childhood and Society. New York, WW Norton, 29. Horowitz grief and Psychiatry 30. Malan York, DH: Plenum, PE: Technique. 1968 MJ, Wilner N, Marmar C, etal: Pathological the activation of latent self-images. Am 1980; The 137:1157-1 Frontier 1976 Short-Term New York, Psychotherapy: Plenum, 1979 in a New Psychotherapy. Key: Psychotherapy Dynamic Evaluation 162 of Brief Psychotherapy. New

M, et al: bereavePsychiatry scale for

nortriptyline in late

1991; 52:307-310 14. Hamilton MA: primary depressive

a rating Journal

31. Sifneos and 32.

of Social S: DevelopPsychiatry

and Clinical Psychology 1967; 6:278-296 15. Faschingbauer TR, DeVaul RA, Zisook ment of the Texas Inventory N, Comes in the Applications treatment of Grief. C, et of al: AmJ 1977; 134:696-698 16. Frank E, Frank psychotherapy sion, in New

Strupp

A Guide

HH, BinderJL: to Time-Limited

Interpersonal late-life depresPsycho-

of Interpersonal

therapy, edited Washington, DC, pp 169-1 75 17. Klerman GL, Interpersonal York, Basic

by Weissman M, Klerman GL. American Psychiatric Press, 1993, MM, Rounsaville of Depression. BJ, et al: New

New York, Basic Books, 1984 33. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766-771 34. Raphael B: Preventive intervention with the recently bereaved. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1450-1454 35. Gallagher DE, Thompson LW: Treatment of major

depressive brief 36. Horowitz disorder MJ, Marmar in older 1982; C, Weiss adult 19:482-490 DS, etal: Brief psychooutpatients with psychotherapies

Weissman Psychotherapy 1984

Books,

JOURNAL

OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

PRACTICE

AND

RESEARCH

162

BEREAVEMENT

IN LATE

LIFE

therapy atry 37. Vachon study 1984;

of bereavement 41:438-448 MIS, of self-help Lyall WAL,

reactions. RogersJ, for

Arch

Gen

Psychi-

40. Marmar trolled group

CR. trial treatment 1988;

Horowitz of brief

MJ,

Weiss

DS, and

et

al: A conAmJ Psytech-

psychotherapy

mutual-help

et al: A controlled widows. L: The health 1986; AmJ impact Psyof and

of conjugal 145:203-209

bereavement.

intervention

chiatry 41. Yalom niques

chiatry 1980; 137:1380-1384 38. Lieberman MA, Videka-Sherman self-help widowers. 39. Lieberman groups AmJ on the mental Orthopsychiatry

ID, Vinogradov and themes

5: Bereavement 1988; 38:419-446 and groups

groups:

of widows 56:435-449 study.

42. Lieberman MA Group properties study of group norms in self-help and widowers. IntJ Group Psychother 208

outcomes: a for widows 1989; 39:191-

M,Yalom

I: Briefgrouppsychotherapyfor a controlled 42:117-132

the spousally bereaved: Group Psychother 1992;

mt J

VOLUMES

#{149}

NUMBER

#{149}

SPRING

1994

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Test Bank For Microbiology Basic and Clinical Principles 1st Edition Lourdes P Norman MckayDocument36 paginiTest Bank For Microbiology Basic and Clinical Principles 1st Edition Lourdes P Norman Mckayshriekacericg31u3100% (43)

- CHCCCS015 Student Assessment Booklet Is (ID 97088) - FinalDocument33 paginiCHCCCS015 Student Assessment Booklet Is (ID 97088) - FinalESRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal SociologyDocument53 paginiCriminal SociologyJackielyn cabayaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physiology of The Cell: H. Khorrami PH.DDocument89 paginiPhysiology of The Cell: H. Khorrami PH.Dkhorrami4Încă nu există evaluări

- Tes TLMDocument16 paginiTes TLMAmelia RosyidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laboratory Test Report: Method: Uricase PeroxidaseDocument10 paginiLaboratory Test Report: Method: Uricase PeroxidaseRamaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- QB BT PDFDocument505 paginiQB BT PDFنيزو اسوÎncă nu există evaluări

- COPD CurrentDocument9 paginiCOPD Currentmartha kurniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Analysis and Reflection On That Sugar FilmDocument2 paginiThe Analysis and Reflection On That Sugar FilmkkkkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meralgia ParaestheticaDocument4 paginiMeralgia ParaestheticaNatalia AndronicÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 - Cannabis Intoxication Case SeriesDocument8 pagini2 - Cannabis Intoxication Case SeriesPhelipe PessanhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amazing Facts About Our BrainDocument4 paginiAmazing Facts About Our BrainUmarul FarooqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preterm Prelabour Rupture of MembranesDocument12 paginiPreterm Prelabour Rupture of MembranesSeptiany Indahsari DjanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Comparative Clinical Evaluation of Eranda Taila Matra Basti With Combination of Mefenamic Acid and Dicyclomine in The Management of Udavartini W.S.R To Primary DysmenorrheaDocument8 paginiA Comparative Clinical Evaluation of Eranda Taila Matra Basti With Combination of Mefenamic Acid and Dicyclomine in The Management of Udavartini W.S.R To Primary DysmenorrheaEditor IJTSRDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peoples of Cambodia 2nd EditionDocument55 paginiPeoples of Cambodia 2nd Editionsummit_go_team100% (1)

- Anatomi & Fisiologi Sistem RespirasiDocument57 paginiAnatomi & Fisiologi Sistem RespirasijuliandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- IC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Document4 paginiIC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Juon Vairzya AnggraeniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Studies-FIRST UNIT-vkmDocument59 paginiEnvironmental Studies-FIRST UNIT-vkmRandomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tamiflu and ADHDDocument10 paginiTamiflu and ADHDlaboewe100% (2)

- China Animal Healthcare: The Healing TouchDocument19 paginiChina Animal Healthcare: The Healing TouchBin WeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Color Atlas of Poultry Diseases by J.L VegadDocument131 paginiA Color Atlas of Poultry Diseases by J.L VegadAbubakar Tahir Ramay95% (63)

- Chemo Stability Chart AtoK 1jun2016Document46 paginiChemo Stability Chart AtoK 1jun2016arfitaaaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Only Book A Teen Will EVER Need To Lose Fat & Build Muscle in The GymDocument146 paginiThe Only Book A Teen Will EVER Need To Lose Fat & Build Muscle in The GymJake Farrugia100% (1)

- Maxime Gorky and KingstonDocument433 paginiMaxime Gorky and KingstonBasil FletcherÎncă nu există evaluări

- SCIT 1408 Applied Human Anatomy and Physiology II - Urinary System Chapter 25 BDocument50 paginiSCIT 1408 Applied Human Anatomy and Physiology II - Urinary System Chapter 25 BChuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Mrna Vaccine Against Sars-Cov-2 - Preliminary Report: Original ArticleDocument12 paginiAn Mrna Vaccine Against Sars-Cov-2 - Preliminary Report: Original ArticleSalvador Francisco Tello OrtízÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plural of Medical Terms UsmpDocument2 paginiPlural of Medical Terms UsmpUSMP FN ARCHIVOSÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Black Death, The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History With DocumentsDocument286 paginiThe Black Death, The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History With DocumentsVaena Vulia100% (7)

- Arthur CrawfordDocument308 paginiArthur CrawfordRupali Mokashi100% (1)

- How Swab Testing of Kitchen SurfacesDocument3 paginiHow Swab Testing of Kitchen SurfacesSIGMA TESTÎncă nu există evaluări