Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Bountiful Noise: Whether in Music or in Nature, Noise Can Be Full of Riches. The Trick Is To Recognize The Treasures

Încărcat de

Dani MartínezDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Bountiful Noise: Whether in Music or in Nature, Noise Can Be Full of Riches. The Trick Is To Recognize The Treasures

Încărcat de

Dani MartínezDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

EDITORIALS

NATURE|Vol 453|8 May 2008

States, legislation saying that budgets ought to be increased is separate from the legislation that actually increases them. And the latter promptly got lost in the governments budgetary meltdown, as Congress year after year fails to approve final numbers for each fiscal cycle until months later than expected. When the fiscal 2008 numbers were approved last December, the funding that Congress had pencilled in for the COMPETES Act and that the agencies had been counting on had disappeared. The resulting turmoil has forced research agencies to put major initiatives on hold, to put employees at national laboratories on unpaid leave, and to pinch pennies everywhere. Many of the Gathering Storm authors in Washington last week were understandably furious. Broken promises are demoralizing, to say the least, and make it impossible for agencies to plan or manage coherently. Still, many of Gathering Storms best ideas could be implemented without waiting for Congress to collectively grow up and show financial responsibility. These ideas include bolstering programmes to train maths and science teachers; getting more students to enrol in advanced courses in high school; providing special funds to help young scientists start their own labs; and making it easier for foreign-born scientists to enter the country. Such measures would still

require action from Congress, the president, or both. But they might very well be faster and easier to implement than the kind of major national commitment outlined in the America COMPETES Act. In addition, it is important for supporters of the competitiveness initiative to remember that they, too, have a responsibility, which is to keep on communicating to legislators and to the American public at large why America COMPETES is more than just a Full Employment For Physical Scientists Act. As David Ferraro of the Seattle-based Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation pointed out at the conference, the hotel ballroom was an echo chamber: Americans elsewhere dont necessarily buy the notion that pouring money into research is the best way to spend their tax dollars. Indeed, some researchers argue that the statistics showing that the United States is falling behind have been misinterpreted (see H. Salzman & L. Lovell Nature 453, 2830; 2008). So, while the Gathering Storm goals are worthy ones (see Nature 437, 1208; 2005), supporters would be well advised to broaden their message beyond the usual suspects. Members of Congress are not going to stay on target for long when their constituents have other pressing issues, such as the economy or the war in Iraq, on their minds.

Bountiful noise

Whether in music or in nature, noise can be full of riches. The trick is to recognize the treasures.

aughter and hisses thats how a London promenade concert audience greeted the world premiere of a revolutionary musical composition in 1912. The response was hardly unusual, given that audiences of the day were regularly having their assumptions challenged by composers bent on redefining Western music. But unlike other dissonant masterpieces of that era, such as Igor Stravinskys The Rite of Spring, the Five Orchestral Pieces of Arnold Schoenberg still come across to many as little more than noise. There are reasons for that, as a series of essays on science and music launched in this issue will make clear. But then, as other articles in todays issue illustrate, noise has its treasures too. Schoenbergs composition deliberately defied all the prevailing standards of music. It was, in his own words, devoid of architecture or construction, just an uninterrupted changing of colours, rhythms, and moods. But it did have an expressive purpose, he insisted: The music seeks to express all that swells in us subconsciously like a dream. Indeed, for todays sympathetic listener, the musical elements are distinctively recognizable and the emotional charge is tangible. Yet the language is still a challenge. Of course, as Philip Ball explains in an Essay in this issue (see page 160), even more traditional music defies all attempts to explain its function in terms of mathematical or cognitive naturalness. Subsequent essays in the series will highlight both the universalities in music for example, how a mothers lullaby and rocking during early childhood are thought to lay a foundation for humans aural and physical responsiveness and musics diversity: the range of cultural conventions in such apparently fundamental elements as

pitch scales and perceptions of rhythm. Essayists will also describe, for example, the challenges in acoustics of allowing audiences to hear music to its best advantage. Drawing on musicology, statistics, cognitive and evolutionary biology and acoustics, the series will help us understand why most of Schoenbergs music is more challenging than that of his contemporary and champion, Gustav Mahler let alone the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. But it will also remind us that none of these disciplines has yet been able to answer the fundamental question: why does music have such The average listener power over us? Nor can they explain isnt the least worried how avant garde composers in the 1950s that musicologists were able to take noise itself and make and scientists cannot something new and true with it. Anyone who has performed Karlheinz Stock- explain why we enjoy hausens Kontakte, for example, which music. pioneered much subsequent electronic music by presenting manipulated electronic noise amid the sounds of percussion and piano, will tell you that the piece has an incomprehensible power. Anyone with an open musical ear who has listened to Gyrgy Ligetis Atmospheres for orchestra will say the same. The average listener isnt the least worried that musicologists and scientists cannot explain why we enjoy music. What matters is that its true bounties are recognized, and then explored and analysed. That applies not only to noise-like music, but also to nature. In that spirit, we can celebrate the fact that seismologists have begun to recognize and unpick the value of the ambient hum of the planet (see page 146). And we can enjoy the positive benefits that noise seems to have on living cells (see page 150). Above all, what matters is that analysis strengthens rather than weakens humankinds sense of wonder even as the natural terrain of exploration gets messier and as great composers make understanding music even more challenging.

134

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- SSNDocument1.377 paginiSSNBrymo Suarez100% (9)

- Notes On The Analysis of Rock Music PDFDocument14 paginiNotes On The Analysis of Rock Music PDFpolkmnnlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guiffre V MaxwellDocument40 paginiGuiffre V MaxwellTechno Fog91% (32)

- Basics of Duct DesignDocument2 paginiBasics of Duct DesignRiza BahrullohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plants Life Cycles and PartsDocument5 paginiPlants Life Cycles and PartsseemaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mathematical Model and Geometrical Progression of The Guitar and The Golden Rectangles-THE BASICS by Yorgos Kertsopoulos PDFDocument27 paginiThe Mathematical Model and Geometrical Progression of The Guitar and The Golden Rectangles-THE BASICS by Yorgos Kertsopoulos PDFИгорь Макаров100% (2)

- Pinch, Sound StudiesDocument14 paginiPinch, Sound StudieshjhjhjhjhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes On The Analysis of Rock MusicDocument14 paginiNotes On The Analysis of Rock MusicpolkmnnlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agnotology: The Science of Creating IgnoranceDocument4 paginiAgnotology: The Science of Creating Ignorancejmac1212Încă nu există evaluări

- Collaboration and Creativity in Popular Songwriting TeamsDocument33 paginiCollaboration and Creativity in Popular Songwriting Teamsvkris71Încă nu există evaluări

- Analysing Popular Music TaggDocument32 paginiAnalysing Popular Music TaggMartinuci AguinaldoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hot Talk, Cold Science: Global Warming's Unfinished DebateDe la EverandHot Talk, Cold Science: Global Warming's Unfinished DebateEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (3)

- B+V ELEVATOR SIDE DOOR Collar Type VS09 A4Document19 paginiB+V ELEVATOR SIDE DOOR Collar Type VS09 A4Игорь ШиренинÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bruno Latour - Will Non-Humans Be SavedDocument21 paginiBruno Latour - Will Non-Humans Be SavedbcmcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Table of Contents and Executive SummaryDocument38 paginiTable of Contents and Executive SummarySourav Ojha0% (1)

- Agawu - Does Music Theory Need MusicologyDocument10 paginiAgawu - Does Music Theory Need MusicologyWillard MylesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14 - Hydraulic Design of Urban Drainage Systems PDFDocument45 pagini14 - Hydraulic Design of Urban Drainage Systems PDFDeprizon SyamsunurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arcelor Mittal - Bridges PDFDocument52 paginiArcelor Mittal - Bridges PDFShamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agawu Kofi - Review de Cook Music Imagination An CultureDocument9 paginiAgawu Kofi - Review de Cook Music Imagination An CultureDaniel Mendes100% (2)

- Effects of War On EconomyDocument7 paginiEffects of War On Economyapi-3721555100% (1)

- Seeger Ethnomusicology PDFDocument16 paginiSeeger Ethnomusicology PDFRastko JakovljevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fact and Value in Contemporary Music ScholarshipDocument6 paginiFact and Value in Contemporary Music ScholarshipAsher Vijay YampolskyÎncă nu există evaluări

- University of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyDocument9 paginiUniversity of Illinois Press Society For Ethnomusicologyriau_82Încă nu există evaluări

- Fact and Value in Contemporary ScholarshipDocument6 paginiFact and Value in Contemporary ScholarshippaulgfellerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tag, Popular Music, 1982Document32 paginiTag, Popular Music, 1982James SullivanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applied Sociology and Performance Studies Charles KeilDocument11 paginiApplied Sociology and Performance Studies Charles KeilAlexandre BrasilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extended Essay On Classical Music - Pre-Dp 2Document7 paginiExtended Essay On Classical Music - Pre-Dp 2Wiktor HaberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On The 80sDocument6 paginiResearch Paper On The 80smrrhfzund100% (1)

- Aofnef (OieDocument7 paginiAofnef (OieWiktor HaberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agawu 2004Document21 paginiAgawu 2004Alejandro BenavidesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stadler, "Breaking Sound Barriers"Document12 paginiStadler, "Breaking Sound Barriers"Gustavus StadlerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Merriam Alan P ETHNOMUSICOLOGY DISCUSSIODocument9 paginiMerriam Alan P ETHNOMUSICOLOGY DISCUSSIOJessica GottfriedÎncă nu există evaluări

- ,analysing Popular Music, Theory, Method and PracticeDocument32 pagini,analysing Popular Music, Theory, Method and PracticeJuan Manuel PellizzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ZOOMUSICOLOGÍADocument19 paginiZOOMUSICOLOGÍAAna María Zapata UrregoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blackwell Publishing American Anthropological AssociationDocument8 paginiBlackwell Publishing American Anthropological AssociationkraanergÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philip Tagg - Analysing Popular Music (Popular Music, 1982)Document22 paginiPhilip Tagg - Analysing Popular Music (Popular Music, 1982)Diego E. SuárezÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Handbook For Sound StudiesDocument4 paginiA Handbook For Sound Studiesguo100% (1)

- Dissertation Topics On Classical MusicDocument5 paginiDissertation Topics On Classical MusicHelpWritingPaperUK100% (1)

- Music Thesis PapersDocument4 paginiMusic Thesis Papersafjrpomoe100% (2)

- Introduction to Philosophy of Science by O'Hear - Growth of Knowledge in Science vs ArtsDocument7 paginiIntroduction to Philosophy of Science by O'Hear - Growth of Knowledge in Science vs ArtsJonnathan AcevedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Musicology?: Professor Nicholas CookDocument5 paginiWhat Is Musicology?: Professor Nicholas CookJacob AguadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper Topics Music CensorshipDocument6 paginiResearch Paper Topics Music Censorshipipkpzjbkf100% (3)

- A Essay About EducationDocument9 paginiA Essay About Educationezknbk5h100% (2)

- An Experimental Music TheoryDocument11 paginiAn Experimental Music TheoryMitia D'AcolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Australian Electronica HistoryDocument21 paginiAustralian Electronica HistoryandersandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music Dissertation Abstracts InternationalDocument8 paginiMusic Dissertation Abstracts InternationalWriteMyCustomPaperUK100% (1)

- Interesting Research Paper Topics About MusicDocument7 paginiInteresting Research Paper Topics About Musicgvzyr86v100% (1)

- Perspectives of New Music Perspectives of New MusicDocument59 paginiPerspectives of New Music Perspectives of New MusicKristupas BubnelisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare EssayDocument7 paginiShakespeare Essaywwpadwwhd100% (2)

- "Displaying Climate Change: Back To Basics?" Soichot & McKenzie, 2011, EcsiteDocument3 pagini"Displaying Climate Change: Back To Basics?" Soichot & McKenzie, 2011, EcsiteMarine SoichotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Essay TopicsDocument6 paginiMedical Essay Topicsyiouokaeg100% (2)

- This Content Downloaded From 186.217.251.140 On Sun, 25 Oct 2020 03:20:59 UTCDocument16 paginiThis Content Downloaded From 186.217.251.140 On Sun, 25 Oct 2020 03:20:59 UTCFranciscoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Editorial Music Education: Why Bother? - ERRATUMDocument4 paginiEditorial Music Education: Why Bother? - ERRATUMAmber DeckersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sound Authorities: Scientific and Musical Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century BritainDe la EverandSound Authorities: Scientific and Musical Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century BritainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music Term Paper OutlineDocument6 paginiMusic Term Paper Outlineaflstfcap100% (1)

- Classical Music Thesis StatementDocument6 paginiClassical Music Thesis Statementkristinacamachoreno100% (2)

- Essays On DowryDocument6 paginiEssays On Dowryqzvkuoaeg100% (2)

- Appropriation of TechnologiesDocument35 paginiAppropriation of TechnologiesSaroni YanthanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Woodstock Essay ThesisDocument6 paginiWoodstock Essay Thesisk1lod0zolog3100% (2)

- Music, The Public Interest, and The Practice of EthnomusicologyDocument5 paginiMusic, The Public Interest, and The Practice of Ethnomusicologyalvian hanifÎncă nu există evaluări

- RMA article explores history and purpose of musicologyDocument10 paginiRMA article explores history and purpose of musicologyElision06Încă nu există evaluări

- University of Illinois Press, Society For Ethnomusicology EthnomusicologyDocument33 paginiUniversity of Illinois Press, Society For Ethnomusicology EthnomusicologyfedoerigoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music History Thesis TopicsDocument6 paginiMusic History Thesis Topicsmmwsmltgg100% (1)

- Slobin 1992-Micromusics - of - The - West-A - Comparative - ApproachDocument88 paginiSlobin 1992-Micromusics - of - The - West-A - Comparative - ApproachMarcela Laura Perrone Músicas LatinoamericanasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monism as Connecting Religion and Science: A Man of ScienceDe la EverandMonism as Connecting Religion and Science: A Man of ScienceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Developmen of Chick EmbryoDocument20 paginiDevelopmen of Chick Embryoabd6486733Încă nu există evaluări

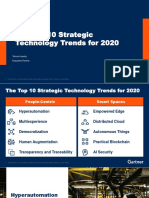

- The Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerDocument31 paginiThe Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerCarlos Stuars Echeandia CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- BILL of Entry (O&A) PDFDocument3 paginiBILL of Entry (O&A) PDFHiJackÎncă nu există evaluări

- COP2251 Syllabus - Ellis 0525Document9 paginiCOP2251 Syllabus - Ellis 0525Satish PrajapatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classification of Methods of MeasurementsDocument60 paginiClassification of Methods of MeasurementsVenkat Krishna100% (2)

- Citation GuideDocument21 paginiCitation Guideapi-229102420Încă nu există evaluări

- Questions - TrasportationDocument13 paginiQuestions - TrasportationAbhijeet GholapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ds 3805Document4 paginiDs 3805sparky2017Încă nu există evaluări

- 1 Univalent Functions The Elementary Theory 2018Document12 pagini1 Univalent Functions The Elementary Theory 2018smpopadeÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Inventory Management?Document31 paginiWhat Is Inventory Management?Naina SobtiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sceduling and Maintenance MTP ShutdownDocument18 paginiSceduling and Maintenance MTP ShutdownAnonymous yODS5VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Indications, Treatment and Current PracticeDocument14 paginiClinical Indications, Treatment and Current PracticefadmayulianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACM JournalDocument5 paginiACM JournalThesisÎncă nu există evaluări

- FRABA - Absolute - Encoder / PLC - 1 (CPU 314C-2 PN/DP) / Program BlocksDocument3 paginiFRABA - Absolute - Encoder / PLC - 1 (CPU 314C-2 PN/DP) / Program BlocksAhmed YacoubÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Patient Self-Determination ActDocument2 paginiThe Patient Self-Determination Actmarlon marlon JuniorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Past Paper Booklet - QPDocument506 paginiPast Paper Booklet - QPMukeshÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 WELD-2022 Ebrochure 3Document5 pagini01 WELD-2022 Ebrochure 3Arpita patelÎncă nu există evaluări

- KG ResearchDocument257 paginiKG ResearchMuhammad HusseinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cost Systems: TermsDocument19 paginiCost Systems: TermsJames BarzoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance of a Pelton WheelDocument17 paginiPerformance of a Pelton Wheellimakupang_matÎncă nu există evaluări

- North American Countries ListDocument4 paginiNorth American Countries ListApril WoodsÎncă nu există evaluări