Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Monopolistic Competition:: Large Number of Small Firms

Încărcat de

Sohaib SangiTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Monopolistic Competition:: Large Number of Small Firms

Încărcat de

Sohaib SangiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Monopolistic Competition:

Monopolistic competition is a market structure characterized by a large number of relatively small firms. While the goods produced by the firms in the industry are similar, slight differences often exist. As such, firms operating in monopolistic competition are extremely competitive but each has a small degree of market control. In effect, monopolistic competition is something of a hybrid between perfect competition and monopoly. Comparable to perfect competition, monopolistic competition contains a large number of extremely competitive firms. However, comparable to monopoly, each firm has market control and faces a negatively-sloped demand curve',500,400)">demand curve. The real world is widely populated by monopolistic competition. Perhaps half of the economy's total production comes from monopolistically competitive firms. The best examples of monopolistic competition come from retail trade, including restaurants, clothing stores, and convenience stores.

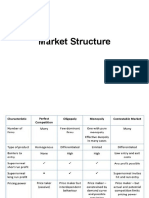

Characteristics

The four characteristics of monopolistic competition are: (1) large number of small firms, (2) similar, but not identical products, (3) relatively good, but not perfect resource mobility, and (4) extensive, but not perfect knowledge. Large Number of Small Firms: A monopolistically competitive industry contains a large number of small firms, each of which is relatively small compared to the overall size of the market. This ensures that all firms are relatively competitive with very little market control over price or quantity. In particular, each firm has hundreds or even thousands of potential competitors. Similar Products: Each firm in a monopolistically competitive market sells a similar, but not absolutely identical, product. The goods sold by the firms are close substitutes for one another, just not perfect substitutes. Most important, each good satisfies the same basic want or need. The goods might have subtle but actual physical differences or they might only be perceived different by the buyers. Whatever the reason, buyers treat the goods as similar, but different. Relative Resource Mobility: Monopolistically competitive firms are relatively free to enter and exit an industry. There might be a few restrictions, but not many. These firms are not "perfectly" mobile as with perfect competition, but they are largely unrestricted by government rules and regulations, start-up cost, or other substantial barriers to entry. Extensive Knowledge: In monopolistic competition, buyers do not know everything, but they have relatively complete information about alternative prices. They also have relatively complete information

about product differences, brand names, etc. Each seller also has relatively complete information about production techniques and the prices charged by their competitors.

Market Structure of Monopolistic Competition: Product Differentiation

The goods produced by firms operating in a monopolistically competitive market are subject to product differentiation. The goods are essentially the same, but they have slight differences. Product differentiation is usually achieved in one of three ways: (1) physical differences, (2) perceived differences, and (3) support services. Physical Differences: In some cases the product of one firm is physically different form the product of other firms. One good is chocolate, the other is vanilla. One good uses plastic, the other aluminum. Perceived Differences: In other cases goods are only perceived to be different by the buyers, even though no physical differences exist. Such differences are often created by brand names, where the only difference is the packaging. Support Services: In still other cases, products that are physically identical and perceived to be identical are differentiated by support services. Even though the products purchased are identical, one retail store might offer "service with a smile," while another provides express checkout.Product differentiation is the primary reason that each firm operating in a monopolistically competitive market is able to create a little monopoly all to itself.

Demand and Revenue

The four characteristics of monopolistic competition mean that a monopolistically competitive firm faces a relatively elastic, but not perfectly elastic, demand curve, such as the one displayed in the exhibit to the right. Each firm in a monopolistically competitive market can sell a wide range of output within a relatively narrow range of prices. Demand is relatively elastic in monopolistic competition because each firm faces competition from a large number of very, very close substitutes. However, demand is not perfectly elastic (as in perfect competition) because the output of each firm is slightly different from that of other firms. Monopolistically competitive goods are close substitutes, but not perfect substitutes. In the exhibit to the right, the monopolistically competitive firm can sell up to 10 units of output within the range of $5.50 to $6.50. Should the price go higher than $6.50, the quantity demanded drops to zero. A monopolistically competitive firm is a price maker, with some degree of control over price. Once again, unlike perfect competition, a monopolistically competitive firm has the ability to raise or lower

the price a little, not much, but a little. And like monopoly, the price received by a monopolistically competitive firm (which is also the firm's average revenue) is greater than its marginal revenue. In the exhibit to the right, the marginal revenue curve (MR) lies below the demand/average revenue curve (D = AR). While marginal revenue is less than price, because demand is relatively elastic, the difference tends to be relatively small. For example, 5 units of output correspond to a $5 price. The marginal revenue for the fifth unit is $4.80, less than price, but not by much.

Demand Curve,Monopolistic competition

Short-Run Production

The analysis of short-run production by a monopolistically competitive firm provides insight into market supply. The key assumption is that a monopolistically competitive firm, like any other firm, is motivated by profit maximization. The firm chooses to produce the quantity of output that generates the highest possible level of profit, given price, market demand, cost conditions, production technology, etc. The short-run production decision for monopolistic competition can be illustrated using the exhibit to the right. The top panel indicates the two sides of the profit decision--revenue and cost. The slightly curved green line is total revenue. Because price depends on quantity, the total revenue curve is not a straight line. The curved red line is total cost. The difference between total revenue and total cost is profit, which is illustrated in the lower panel as the brown line. A firm maximizes profit by selecting the quantity of output that generates the greatest gap between the total revenue line and the total cost line in the upper panel, or at the peak of the profit curve in the lower panel. In this example, the profit maximizing output quantity is 6. Any other level of production generates less profit.

Short run production,Monopolistic competition

Long-Run Production

In the long run, with all inputs variable, a monopolistically competitive industry reaches equilibrium at an output that generates economies of scale or increasing returns to scale. At this level of output, the negatively-sloped demand curve is tangent to the negatively-sloped segment of the long run-average cost curve. This is achieved through a two-fold adjustment process. The first of the folds is entry and exit of firms into and out of the industry. This ensures that firms earn zero economic profit and that price is equal to average cost. The second of the folds is the pursuit of profit maximization by each firm in the industry. This ensures that firms produce the quantity of output that equates marginal revenue with short-run and long-run marginal cost. Because a monopolistically competitive firm has some market control and faces a negatively-sloped demand curve, the end result of this long-run adjustment is two equilibrium conditions:

MR = MC = LRMC P = AR = ATC = LRAC With marginal revenue equal to marginal cost, each firm is maximizing profit and has no reason to adjust the quantity of output or factory size. With price equal to average cost, each firm in the industry is earning only a normal profit. Economic profit is zero and there are no economic losses, meaning no firm is inclined to enter or exit the industry. These conditions are satisfied separately. However, because price is not equal to marginal revenue, the two equations are not equal (unlike perfect competition). This further means that monopolistic competition does NOT achieve long-run equilibrium at the minimum efficient scale of production.

Real World (In)Efficiency

A monopolistically competitive firm generally produces less output and charges a higher price than would be the case for a perfectly competitive industry. In particular, the price charged by a monopolistically competitive firm is greater than its marginal cost. The inequality of price and marginal cost violates the key condition for efficiency. Resources are NOT being used to generate the highest possible level of satisfaction. The reason for this inefficiency is found with market control. Because a monopolistically competitive firm has control over a small slice of the market, it faces a negatively-sloped demand curve and price is greater than marginal revenue, which is set equal to marginal cost when maximizing profit. While monopolistic competition is technically inefficient, it tends to be less inefficient than other market structures, especially monopoly. Even though price is greater than marginal revenue (and thus marginal cost), because the demand curve is relatively elastic, the difference is often relatively small. For example, a monopoly that charges a $100 price while incurring a marginal cost of $20 creates a serious inefficiency problem. In contrast, the inefficiency created by a monopolistically competitive firm that charges a $50 price while incurring a marginal cost of $49.95 is substantially less. The closer marginal revenue is to price, the closer a monopolistically competitive firm comes to allocating resources according to the efficiency benchmark established by perfect competition. In the grand scheme of economic problems, the inefficiency created by monopolistic competition seldom warrants much attention... and deservedly

Monopolistic competition in managerial decisions:

Implication of Product Differentiation: Advertising Decisions As mentioned above, monopolistically competitive firms differentiate their products in order to have some control over the price. In this case, the products are not perfect substitutes, and this makes the demand less than perfectly elastic. The implication of this is that some consumer wont switch when the prices go up within a limit, while others are willing to switch. To keep the other consumers from switching to the substitutes, firms under monopolistic competition spend a lot of money on advertising. There are two kinds of advertising under monopolistic competition. 1) Comparative Advertising: This involves campaigns designed to differentiate a given firms brand from brands sold by competing firms. Comparative advertising is common in the fastfood industry, where firms such as McDonalds attempt to simulate demand for their hamburgers by differentiating them from competing brands. This may induce consumers to pay a premium for a particular brand. This additional value for a brand in the price is called brand equity. 2) Niche Marketing: Firms under monopolistic competition frequently introduce new products. The products could be totally new or new improved. Firms can also advertise a product that fills special needs in the market. This advertising strategy targets a special group of consumers. For example green marketing advertise environmentally friendly products to target the segment of the society that is concerned with the environment. The firm packages a product with materials that are recyclable.

These advertising strategies can bring positive profits in the shortrun. In the longrun other firms will mimic their strategy and reduce profits to zero.

Optimal Advertising Decisions Optimal advertising is determined by the following formula Formula: The profit maximizing advertising-to-sales ratio. A/R = [(EQ, A) / - (EQ, P)] > 0,

where A is expenditure on advertising and R is sales revenue. Note: A/R is a positive fraction because (EQ, P) is already negative and multiplied by a minus). EQ, A = %Q / %A = (Q / A)*(A/Q) is advertising elasticity of demand, and

EQ, P = %Q / %P = (Q / P)*(P / Q), is the ownprice direct elasticity of demand, which is negative.

If EQ, P = - (demand is perfectly price elastic under perfect competition), then A/R = 0. That is, the optimal advertising-to-sales ratio is zero for the perfectly competitive firm. The more elastic the demand with respect to own price (i.e., products are less differentiated and more substitutable), the lower the optimal advertising-to-sales ratio. This is a case of more competition than less, and there is not much need for advertising. The more elastic the demand with respect to advertising, the higher the optimal advertising- tosales ratio.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Terms and Conditions For Loyalty ProgramDocument2 paginiTerms and Conditions For Loyalty ProgramSportspower WarrnamboolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Porter's Five Forces: Understand competitive forces and stay ahead of the competitionDe la EverandPorter's Five Forces: Understand competitive forces and stay ahead of the competitionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (10)

- Startup India Seed Fund Scheme: Startup Sample Pitch DeckDocument13 paginiStartup India Seed Fund Scheme: Startup Sample Pitch DeckSimran KhuranaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dynamics of Internal Environment in BusinessDocument23 paginiDynamics of Internal Environment in Businesslionviji50% (2)

- Theory of Market: Perfect Competition: Nature and Relevance Monopoly and Monopolistic Competition OligopolyDocument18 paginiTheory of Market: Perfect Competition: Nature and Relevance Monopoly and Monopolistic Competition OligopolyDivyanshu BargaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solution Manualch13Document33 paginiSolution Manualch13StoneCold Alex Mochan80% (5)

- BIM Maturity MatrixDocument7 paginiBIM Maturity MatrixRicardo FreitasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oligopoly:: Firm Industry Monopoly Monopolistic CompetitionDocument19 paginiOligopoly:: Firm Industry Monopoly Monopolistic CompetitionBernard Okpe100% (2)

- Monopolistic Competition - Written ReportDocument11 paginiMonopolistic Competition - Written ReportEd Leen Ü92% (12)

- Chap 8 - Managing in Competitive, Monopolistic, and Monopolistically Competitive MarketsDocument48 paginiChap 8 - Managing in Competitive, Monopolistic, and Monopolistically Competitive MarketsjeankerlensÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effective Comunication SkillsDocument36 paginiEffective Comunication SkillsScarlet100% (5)

- niir-directory-database-india-professionals-architects-interior-decorators-building-contractors-property-dealers-real-estate-agents-brokers-developers-builders-delhi-amp-ncr-region-construction-materialsDocument11 pagininiir-directory-database-india-professionals-architects-interior-decorators-building-contractors-property-dealers-real-estate-agents-brokers-developers-builders-delhi-amp-ncr-region-construction-materialsDoctor SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer-Brand Relationships in Step-Down Line Extensions of Luxury and Designer BrandsDocument25 paginiConsumer-Brand Relationships in Step-Down Line Extensions of Luxury and Designer BrandsSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cafe ProposalDocument14 paginiCafe ProposalSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crafting Strategy - Summary'sDocument3 paginiCrafting Strategy - Summary'sShivam Kumar91% (11)

- A Market Structure Characterized by A Large Number of Small FirmsDocument9 paginiA Market Structure Characterized by A Large Number of Small FirmsSurya PanwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume of Principles of Economics: Firms in Competitive Market (Chapter 14)Document4 paginiResume of Principles of Economics: Firms in Competitive Market (Chapter 14)Wanda AuliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Pure MonopolyDocument5 paginiMonopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Pure MonopolyImran SiddÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Monopolistic CompetitionDocument9 paginiWhat Is Monopolistic CompetitionParag BorleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group4 BSA 1A Monopolistic Competition Research ActivityDocument11 paginiGroup4 BSA 1A Monopolistic Competition Research ActivityRoisu De KuriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of Market Reviewer QuizDocument3 paginiTypes of Market Reviewer QuizJackie Lyn Bulatao Dela PasionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument19 paginiMonopolistic Competitiondev.m.dodiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 9Document16 paginiChapter 9BenjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolies That Make Super Normal Profits Are Always Against Public Interest Because They Could Charge A Lower Price Than They DoDocument4 paginiMonopolies That Make Super Normal Profits Are Always Against Public Interest Because They Could Charge A Lower Price Than They DohotungsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Micro 7 and 8Document36 paginiMicro 7 and 8amanuelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument17 paginiMonopolistic CompetitionAlok ShuklaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2010 Chpt11answersDocument6 pagini2010 Chpt11answersMyron JohnsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument15 paginiMonopolistic Competitionvivekmestri0% (1)

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument5 paginiMonopolistic CompetitionSyed BabrakÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECON 2 Module CHAP 5 Market Structure and Imperfect CompetitionDocument15 paginiECON 2 Module CHAP 5 Market Structure and Imperfect CompetitionAngelica MayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economics AssignmentDocument4 paginiEconomics AssignmentFarman RazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 16 - MicroeconomicsDocument9 paginiChapter 16 - MicroeconomicsFidan MehdizadəÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly 1Document6 paginiMonopolistic Competition and Oligopoly 1Katrina LabisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit III Monopolistic CompitionDocument6 paginiUnit III Monopolistic CompitionPrashant ShahaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 7 Market Structures Teacher NotesDocument10 paginiChapter 7 Market Structures Teacher Notesresendizalexander05Încă nu există evaluări

- EconomicsDocument2 paginiEconomicsIrish Mae T. EspallardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument10 paginiMonopolistic CompetitionDharmaj AnajwalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopoly and Monopolist Competition: DefinitionDocument6 paginiMonopoly and Monopolist Competition: DefinitionLavanya KasettyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 4 CC 4 PDFDocument49 paginiUnit 4 CC 4 PDFKamlesh AgrawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic Competition-1Document24 paginiMonopolistic Competition-1Rishbha patelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presetation On Perfectly Competittive Market Vs Monopoly: Rafi Ahmed (11100100030)Document16 paginiPresetation On Perfectly Competittive Market Vs Monopoly: Rafi Ahmed (11100100030)Rafi AhmêdÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Government Policies Might Be Used To Counteract The Problems That Result From High Barriers To Entry?Document3 paginiWhat Government Policies Might Be Used To Counteract The Problems That Result From High Barriers To Entry?Trisha VelascoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perfect Competition Describes Markets Such That No Participants Are Large Enough To HauctDocument17 paginiPerfect Competition Describes Markets Such That No Participants Are Large Enough To HauctRrisingg MishraaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Market StructureDocument3 paginiMarket StructureJoshua CaraldeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic Competition: Registration For Wikiconference India 2011, Mumbai Is Now OpenDocument6 paginiMonopolistic Competition: Registration For Wikiconference India 2011, Mumbai Is Now Openakhilthambi123Încă nu există evaluări

- Project ReportDocument10 paginiProject ReportfarhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter Review 15Document4 paginiChapter Review 15Tória RajabecÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jawapan Saq 3 LatestDocument3 paginiJawapan Saq 3 LatestAre HidayuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managerial EconDocument5 paginiManagerial EconJulienne CaitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task Monopolistic CompetitionDocument2 paginiTask Monopolistic CompetitionmulianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic Comeptition: M. Shivarama Krishna 10HM28Document19 paginiMonopolistic Comeptition: M. Shivarama Krishna 10HM28Powli HarshavardhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument4 paginiMonopolistic CompetitionCookie LayugÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment - Market StructureDocument5 paginiAssignment - Market Structurerhizelle19Încă nu există evaluări

- 8 - Managing in Competitive, Monopolistic, and Monopolistically Competitive MarketsDocument6 pagini8 - Managing in Competitive, Monopolistic, and Monopolistically Competitive MarketsMikkoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECO 204 Final PaperDocument9 paginiECO 204 Final Paperfields169Încă nu există evaluări

- Economics Notes Nec CH - 5 StuDocument11 paginiEconomics Notes Nec CH - 5 StuBirendra ShresthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applied Ec 6Document9 paginiApplied Ec 6CallistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Market Structure NotesDocument8 paginiMarket Structure NotesABDUL HADIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economics AssignmentDocument21 paginiEconomics AssignmentMichael RopÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economics Chap 13 ReviewDocument5 paginiEconomics Chap 13 ReviewAnonymous EBW1hy64Q1Încă nu există evaluări

- Characteristics of OligopolyDocument3 paginiCharacteristics of OligopolyJulie ann YbanezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competition, Profit and Other Objectives: What Does Normal Profit Mean?Document7 paginiCompetition, Profit and Other Objectives: What Does Normal Profit Mean?Ming Pong NgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monopoly Equilibrium UploadedDocument10 paginiMonopoly Equilibrium Uploadedasal661Încă nu există evaluări

- Zishan Eco AssignmentDocument5 paginiZishan Eco AssignmentAnas AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practice Questions For Quiz 4 With SolutionsDocument6 paginiPractice Questions For Quiz 4 With SolutionsvdvdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Price and Output Under A Pure MonopolyDocument5 paginiPrice and Output Under A Pure MonopolysumayyabanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of Market and Price DeterminationDocument4 paginiTypes of Market and Price DeterminationSaurabhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Market StructureDocument19 paginiMarket StructureSri HarshaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perfect and Imperfect CompetitionDocument7 paginiPerfect and Imperfect CompetitionShirish GutheÎncă nu există evaluări

- AssignmentDocument3 paginiAssignmentSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electronic CommerceDocument46 paginiElectronic CommerceSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- TarmacDocument14 paginiTarmacSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Anjum PDFDocument31 paginiDr. Anjum PDFfaiqsattarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corrugated PackagesDocument19 paginiCorrugated PackagesSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 Good Business Habits We Can Learn From Prophet MuhammadDocument3 pagini7 Good Business Habits We Can Learn From Prophet MuhammadSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- EcommerceDocument3 paginiEcommerceSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study CSM Entry Strategy of An Asian Car Manufacturer in The Swiss MarketDocument8 paginiCase Study CSM Entry Strategy of An Asian Car Manufacturer in The Swiss MarketMrs. Deepika JoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children AdvertisingDocument23 paginiChildren AdvertisingSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gourmet Foods FinalDocument86 paginiGourmet Foods FinalSohaib Sangi100% (1)

- Submitted To: Sir Nadir MagsiDocument52 paginiSubmitted To: Sir Nadir MagsiSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority ORDINANCE-2002Document32 paginiPakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority ORDINANCE-2002Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- News PaperDocument60 paginiNews PaperSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- JFMM 08 2013 0096Document21 paginiJFMM 08 2013 0096Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hot Air Ballon. FinalDocument44 paginiHot Air Ballon. FinalSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Get FileDocument135 paginiGet FileSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jrim 02 2014 0007Document24 paginiJrim 02 2014 0007Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Criteria For Choosing Brand ElementsDocument99 paginiFinal Criteria For Choosing Brand ElementsSohaib Sangi100% (1)

- Jrim 02 2014 0007Document24 paginiJrim 02 2014 0007Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beef BookDocument49 paginiBeef Bookpynhun612Încă nu există evaluări

- Ejm 10 2012 0627Document22 paginiEjm 10 2012 0627Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ebr 11 2013 0132Document19 paginiEbr 11 2013 0132Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supplementary Services in Banking FirmsDocument39 paginiSupplementary Services in Banking FirmsSohaib Sangi0% (1)

- Ebr 11 2013 0132Document19 paginiEbr 11 2013 0132Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ejm 10 2012 0627Document22 paginiEjm 10 2012 0627Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apjml 10 2014 0148Document18 paginiApjml 10 2014 0148Sohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project ShaktiDocument48 paginiProject ShaktiSohaib SangiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supply Chain Management - Applications and Simulations - M. Habib (Intech, 2011) WWDocument264 paginiSupply Chain Management - Applications and Simulations - M. Habib (Intech, 2011) WWEddie MylesÎncă nu există evaluări

- ResearchDocument22 paginiResearchAbegail BlancoÎncă nu există evaluări

- UC Course - Marketing Communication Strategy - Work1Document30 paginiUC Course - Marketing Communication Strategy - Work1ChefJumboTheSoundchefÎncă nu există evaluări

- P&G Group8 FinalDocument24 paginiP&G Group8 FinalFernando Williams100% (1)

- The Cultural Knowledge Perspective: Insights On Resource Creation For Marketing Theory, Practice, and EducationDocument13 paginiThe Cultural Knowledge Perspective: Insights On Resource Creation For Marketing Theory, Practice, and EducationEstudanteSaxÎncă nu există evaluări

- History: Nature Home (China) Co., LTDDocument3 paginiHistory: Nature Home (China) Co., LTDLeonel Chih-Shan MessiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syl Ato Jan 15Document4 paginiSyl Ato Jan 15anilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Putanginang Thesis Nanaman!Document2 paginiPutanginang Thesis Nanaman!Iannie May ManlogonÎncă nu există evaluări

- RiriDocument89 paginiRiriCitraaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sales Marketing Manager Building Materials in Albany NY Resume Christopher MicardiDocument3 paginiSales Marketing Manager Building Materials in Albany NY Resume Christopher MicardiChristopherMicardiÎncă nu există evaluări

- SHORT ANSWERS (8 Marks) What Is Price Discrimination? Explain The Basis of Price DiscriminationDocument36 paginiSHORT ANSWERS (8 Marks) What Is Price Discrimination? Explain The Basis of Price DiscriminationSathish KrishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alice Hooper's TIE Case Study - CPP/Arcos/Alice/Leo BurnettDocument129 paginiAlice Hooper's TIE Case Study - CPP/Arcos/Alice/Leo BurnettThe International Exchange (aka TIE)Încă nu există evaluări

- Data HyundaiDocument16 paginiData Hyundaivishal kashyapÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1.budgeting QuestionDocument4 pagini1.budgeting QuestionPriyahemaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- MASTER Hyperion Performance Scorecard OverviewDocument36 paginiMASTER Hyperion Performance Scorecard OverviewmadangarliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15 Strength 7 ElevenDocument3 pagini15 Strength 7 ElevenPavitra ThinakaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- mcd2050 WK 5 Quiz 2020 01Document3 paginimcd2050 WK 5 Quiz 2020 01Maureen EvangelineÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10key Decision AreasDocument18 pagini10key Decision AreasPham Gia Khiem (BTECHN)Încă nu există evaluări

- Managerial SkillsDocument136 paginiManagerial SkillsdiannevavenidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Insurance Policy-A Case Study Project at Bajaj AllianzDocument35 paginiLife Insurance Policy-A Case Study Project at Bajaj AllianzrupalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Management Paper 1 Case Study HLSL PDFDocument4 paginiBusiness Management Paper 1 Case Study HLSL PDFAmerico Mallma SonccoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Critique: A Literature Review of Corporate GovernanceDocument11 paginiJournal Critique: A Literature Review of Corporate GovernanceAudrey Kristina MaypaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CVP AnalysisDocument7 paginiCVP AnalysisKat Lontok0% (1)

- A Business Owner's Guide: Transform Your Business With SystemsDocument11 paginiA Business Owner's Guide: Transform Your Business With SystemsswapneelbawsayÎncă nu există evaluări