Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

How I Use Electropalatography (1) : Moving Forward With EPG

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

How I Use Electropalatography (1) : Moving Forward With EPG

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

COVER STORY / HOW I USE EPG (1)

How I use electropala

Ann and Gabriel, www.sergiojoselovsky.se

22

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2008

COVER STORY / HOW I USE EPG (1)

atography

When articulation difficulties seem intractable, a visual feedback system called Electropalatography (EPG) may be of benefit - but its availability is still mainly limited to specialist centres and networks. Our two case based articles consider the practicalities and scope of using EPG, the first for two boys with dysarthria as a result of cerebral palsy and the second for a man in his thirties with articulatory dyspraxia following a stroke.

Moving forward with EPG

Ann Nordberg

How I use electropalatography (1)

When traditional therapy techniques were not proving effective with two boys who have dysarthria due to dyskinetic cerebral palsy, Ann Nordberg, Elvira Berg, Goran Carlsson and Anette Lohmander offered them the chance to try real-time visual feedback through Electropalatography, with promising results.

he exact prevalence of communication disorders associated with cerebral palsy is not known, but many children with this Elvira Berg diagnosis experience difficulties ranging from a mild motor speech disorder to being fully non-verbal (Pennington et al., 2005). In children with dyskinetic (also known as athetoid) and spastic cerebral palsy, omission errors tend to exceed substitutions of phonemes, a feature that typically developing children normally do not show in their speech development. Children with dyskinetic dysarthria may also experience respiratory problems, such as paradoxical or reverse breathing and air rushes through the vocal tract that result in no phonation (Hardy, 1983), which may have negative effects on speech performance. Limitations in pitch and loudness due to increased subglottal pressure are common as is velopharyngeal dysfunction. In traditional speech and language therapy approaches for children with cerebral palsy, clinicians have used a variety of techniques to help establish a particular articulation placement (Strand, 1995). Such techniques include mirrors for visual feedback, providing verbal descriptions of target placements, and using fingers to manipulate the articulators. These techniques may help the children to move on to imitation or responding to auditory stimulation, which can be a starting point for many conventional treatment regimes. However, effectiveness has not been Figure 1 Palatal plate proven.

We were working with two Swedish boys aged 7;4 and 10;1 years who both presented with moderate to severe motor speech disorders including deviant articulation of /t/ due to dyskinetic cerebral palsy. They had received lots of speech and oral motor therapy without significant improvement, and we were looking for an alterative. Electropalatography (EPG) is a technique which records the location and the timing of tongue contacts with the hard palate during continuous speech. In Europe, the EPG system was originally developed at Reading University, UK. It consists

of 62 electrodes in an individually designed palatal plate (figure 1) connected to either a computer or a Portable Training Unit (figure 2) (Hardcastle et al., 1991). On the screen the participant is presented with real time visual feedback on tongue palate contacts (figure 3, p.24). The use of visual feedback through EPG represents a relatively new approach to clinical management of speech disorders. Results have suggested positive outcomes for at least some clinical populations, especially those who have failed to respond to other treatment approaches and those who, having received speech and language therapy for some time, have reached a plateau where no progress is being made (Hardcastle et al.,1991). One previous case study reported outcomes using EPG in therapy for velar fronting for a

READ THIS IF YOU WANT TO EXPLORE ALTERNATIVES TO TRADITIONAL TECHNIQUES CARRY OUT CLINICAL CASE STUDIES GET INSIDE A CLIENTS MOUTH

Figure 2 Portable Training Unit

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2008

23

COVER STORY / HOW I USE EPG (1)

Figure 3 Real time visual feedback

child with articulation disorders associated with mild cerebral palsy (Gibbon & Wood, 2003). In their study successful outcomes as well as important diagnostic features of the childs articulation disorder were revealed. We therefore felt it would be worth trying visual feedback of tongue positions through EPG with the two boys. We met with them and their parents to discuss our plans for a clinical study, and they gave their informed consent.

Bjorn

Our first participant has a mild dyskinetic cerebral palsy due to severe perinatal asphyxia. By the time of the study he was 10;1 years old, had been assessed by an educational psychologist to be of average intelligence and was successfully integrated into a mainstream school. He presented with a mild general motor coordination disorder and walked without aids. There was no documented visual or hearing impairment. Using a screening test (Hellquist, 1982) we found his comprehension to be at an average level. Pre-school, between 4;0-6;0 years, Bjorn had received regular speech and language therapy once a week. At the end of this he produced phonemes with a retracted oral articulation, so that dental phonemes were articulated at a posterior oral place, often velar. At school between 7;0-9;10 years he received speech training from 24

one of his teachers supervised by a speech and language pathologist. The training included different oral non-speech exercises. Multiple auditory-visual stimulation was also used - Bjorn looked and listened to the teacher who produced a sound or a word which he then tried to imitate. The sessions often took place in front of a mirror to try to get more awareness of the speech movement patterns. At the start of the study an impressionistic auditory analysis by Ann Nordberg showed that Bjorn had a generally retracted oral place of articulation in production of some phonemes, for example /t/. Intelligibility in spontaneous speech was significantly reduced and he had difficulty sustaining intensity when he was tired.

Gabriel

Our second participant, Gabriel, has a moderate dyskinetic cerebral palsy due to severe asphyxia. He walks with a walker and with high braces. At the start of the study he was 7;4. Like Bjorn, he had been assessed by an educational psychologist to be of average intelligence and was successfully integrated in a mainstream school. There was no documented visual or hearing impairment and we found his comprehension to be at an average level on a screening test (Hellquist, 1982). From the age of 4;0-6;2 years Gabriel had lots of speech training, often once a week with a

speech and language pathologist. After starting school at the age 6;5 years his personal assistant and teacher were supervised by a speech and language therapist and, until the beginning of our study, he had had short periods of oral motor and speech training up to three times a week. The speech exercises were very much the same as the ones described for Bjorn. At the start of our study an impressionistic auditory analysis by Ann Nordberg showed that Gabriel had a severe motor speech disorder and, according to his parents and teachers, the intelligibility of his speech in spontaneous speech / conversation was poor. His speech rate was slow and he had difficulty coordinating breathing and speech production. His speech errors varied in different words. He had both omissions (such as the initial phoneme /t/ for the Swedish word /ti:gr/) and substitutions of the same phoneme. The initial /t/ in another Swedish word /to:/ sounded more like a velar plosive. He also reduced consonant clusters. The movement of his articulators varied a lot, causing many types of speech errors.

The study

For the study, Bjorn and Gabriel each had a personal individual EPG palatal plate made in cooperation with the Department of Odontology, Gteborg University, Sweden and Incidental Ltd in Newcastle, UK.

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2008

COVER STORY / HOW I USE EPG (1)

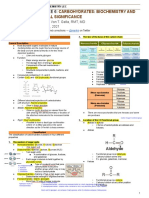

Figure 4 Exercises and goals Week Exercises 1 Learn to place the EPG palate correctly. Test different tongue-palate patterns. Goal Discover the relation between the movements of the tongue and different tongue palate patterns on the display of the Portable Training Unit. To reach an anterior place of articulation when producing /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/. Manage to create a horseshoe shape for /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/. Stabilise an anterior production of /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/. To reach an anterior place of articulation when producing /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/. To reach an anterior place of articulation when producing /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/.

Production of syllables with the sound initial /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ followed by a vowel and look at the display; vary between anterior and posterior place of articulation. Production of words containing /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ in an initial position. Production of /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ (all positions) in words. The boys were told to do this a) looking at the EPG display and b) not looking at it. Production of two word phrases containing /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ (initial position).

3 4

5 6 7 8

Production of two word phrases containing /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ (all positions).

Production of three and four word sentences containing To generalise the anterior place of /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/. articulation for /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ in single words to sentences. Short stories containing words and sentences with /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ (all positions). To generalise the anterior place of articulation for /t/, /d/, /n/ and /s/ in words and sentences to a more complex short story.

word, were presented with the first seven words from the pre-treatment recording, the following seven from the post-treatment recording, alternating in this way until the end of the test. We instructed the listeners simply to write down what they perceived the participants said. We inserted a five second pause between each word to ensure that the listeners would have enough time to write down their answers. Out of the three judgments for each boy, we are reporting the median (where two correct and one incorrect answer is considered as correct, while two incorrect and one correct answer is considered incorrect). We calculated agreement between the listeners point by point as a percentage. The agreement between listeners, including all words and both participants, was 75 per cent. Agreement in words without the target sound was 72 per cent (Bjorn) and 59 per cent (Gabriel).

Bjorns results

Before EPG therapy Bjorn consistently produced the target /t/ with retracted tongue-palate contact, mostly at the palatal (figure 5) and velar place of articulation. The contact pattern varied, even for words with the same vowel context. Fricative pronunciation of the targeted initial /t/ was noticed, for example in the word /to:g/.

Figure 5 Bjorn saying Swedish word /to:/ before EPG therapy

We assessed them with EPG on two occasions, once before EPG therapy and then again after 8 weeks of therapy. For Bjorn we made a third registration with EPG at a follow-up after 11 weeks, when he asked for additional training. The boys articulation was assessed with the palatal plate using EPG (computer-based), and without it, through recording the same words on an audio tape. All recordings took place at the Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Division of Speech and Language Pathology, Sahlgrenska Academy at Gteborg University. In the assessment with the EPG palatal plate, we encouraged Bjorn and Gabriel to name 35 pictures from the Swedish Articulation and Nasality TEst (SVANTE) (Lohmander et al., 2005) and another 35 which we added to increase the number of test words. There were five words with initial /t/ (teve, t, tg, tng, trta) and three with final /t/ (vit, hatt, katt) among the 70. As each was repeated three times, the total number of words containing /t/ was 15 with an initial /t/ and 9 words with a final /t/. To assess intelligibility 35 of the single words in SVANTE (Lohmander et al., 2005) were audio recorded without the EPG palatal plate before the treatment and 35 after. We used a digital tape recorder (Sony Digital audio Recorder PCMR300) and a microphone (Sony Microphone ECM-M3957). The word lists contained different consonants but nine with initial or final /t/. We lent each family a Portable Training Unit, and the therapy took place primarily at home where the boys practised with the unit 15 minutes each day, five days a week over eight weeks, supervised by their parents. Bjorn followed this instruction, but for Gabriel and his family this intensity was too high because he also had a physiotherapy program to complete. He therefore practised approximately 15 minutes a day for three days a week. Once a week the boys and one of their parents met their speech and language

pathologist for advice on how to practise during the coming week. All other speech training was cancelled during this period. As both boys had a retracted oral articulation of the targeted /t/ before therapy, the exercises contained syllables and words with /t/. However, the exercises also contained material with the other Swedish dental phonemes based on our belief that this would facilitate establishment of the target place of articulation. The phonemes were placed in initial, medial and final positions followed by a vowel. At the beginning of the training period there were syllables and words containing the phonemes and later on in sentences and at last in a short story (figure 4). The participants constantly had visual feedback from the Portable Training Unit in the training phase. We located the EPG frame of maximum contact between tongue and palate for each /t/ in the test words and, in order to find differences in production before and after therapy, we calculated values for Centre of Gravity and Alveolar Total. Low Centre of Gravity values correspond to posterior tongue palate contact and high values to anterior tongue palate contact. The Alveolar Total value ranges from 0 to 14 where 14 indicates that all the14 contacts in the first two anterior rows of the EPG palatal plate are activated (Hardcastle et al., 1991). We compared the measures before and after therapy using the Wilcoxon matched pair test. We engaged three adults with no experience of deviant speech for each participant to evaluate any change in the intelligibility of the boys speech. To avoid a learning effect, we only allowed the listeners to listen to the speech material once. During the recordings we suspected that the performance of the boys differed across the test due to loss of concentration and tiredness, especially towards the end. We therefore split the 70 words of the test into ten parts and the listeners, who were blinded as to the timing of the recording of the

After EPG therapy Bjorn showed a more correct anterior placement for his tongue palate contacts for the targeted initial /t/. In 10 of the 15 words with initial /t/ he had full alveolar contact from row 1 as is illustrated in figure 6, which is similar to the adult target in figure 7. Figure 6 also highlights an unusually long stop closure duration which we would not have been aware of without EPG. After EPG therapy Bjorn no longer had fricative pronunciation of initial /t/.

Figure 6 Bjorn saying Swedish word /to:/ after EPG therapy

Figure 7 Adult target of Swedish word /to:/

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2008

25

COVER STORY / HOW I USE EPG (1) For the targeted final /t/ the placement of the tongue varied before therapy. Out of the nine words five showed some alveolar contact. After therapy there was a stable anterior placement of the tongue, with full alveolar contact, for all words with final /t/. The number of alveolar contacts increased from 1.33 to 11.27 and the measure of the greatest concentration contact (Centre of Gravity) changed significantly from 2.88 to 4.18. A similar change was seen for final /t/. Bjorns extra follow-up showed no change in the values of Centre of Gravity and Alveolar Total for either initial or final /t/. The perceptual evaluation indicated that the intelligibility of single word utterances for Bjorn increased from 22/35 words from the pre-treatment recording to 29/35 words from the post-treatment recording (63 per cent to 83 per cent accuracy) including all words, that is both with and without /t/. However, the agreement between listeners was only 72 per cent. The perceptual evaluation showed that Gabriel had generally very low intelligibility scores before therapy and showed no improvement after therapy. His intelligibility score for single word utterances was constant at 9/35 words, that is, 26 per cent accuracy. However, the agreement between listeners was only 59 per cent. production of different phonemes are so subtle and automatic. EPG therefore seems to be a very useful tool in providing the feedback and awareness required to remediate speech errors even in relatively severe motor speech disorders. Another advantage is the fact that the feedback provided through EPG is objective and offered in real time (Hardcastle et al., 1991). Before any generalisation can be made further evaluation with an amended study design is needed. In future we would want to explore the ecological validity of the treatment to find out whether it can improve intelligibility in a social context (WHO, 2001). What we can say is that it seems to us a promising tool for individuals with speech disorders due to cerebral palsy. Ann Nordberg is a speech and language pathologist with the Disability Administration, Region Vastra Gotaland, Sweden, e-mail ann.nordberg@ vgregion.se. Elvira Berg is a speech and language pathologist with Habiliteket AB, Taby, Stockholm, Sweden, Goran Carlsson is a psychologist at the Department of Pediatrics, University of Schleswig-Holstein/Campus Kiel, Germany and Anette Lohmander is Professor at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation, Division of Speech and Language Pathology, Sahlgrenska Academy at Gteborg University, Sweden.

Overall aim

Rating of intelligibility in connected speech may have been more revealing. Gabriels results

Before EPG therapy Gabriel had varying tongue-palate contacts for the target /t/. Initial /t/ showed no tongue-palate contact at all because the plosive /t/ was omitted. At other times there was a little lateral velar contact. After EPG therapy the tongue-palate contact patterns for the target initial /t/ were more stabilised at the correct alveolar place of articulation. He also succeeded in producing closure in all the targeted initial /t/, which he did not before EPG therapy, and initial /t/ was not omitted in any of the words. The number of alveolar contacts increased from 2.43 before therapy to 13.33 after and the Centre of Gravity values significantly from 2.43 to 13.33.

The overall aim of this clinical study was to find out if Electropalatography could be at all useful in treating and diagnosing speech errors related to dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Both boys had changes in EPG patterns which demonstrated a more stable anterior place of articulation. The EPG also highlighted Bjorns unusually long stop closure duration. A merit of EPG in the therapeutic work with Gabriel was that the visual feedback made it possible to see that he reached the dental place of articulation for the target /t/. In his case treatment needs to address respiration and phonation instead of articulation to try to improve his intelligibility. We didnt know this before his speech was evaluated by EPG, so it gave a secondary diagnostic benefit. Only Bjorn showed improvement in intelligibility in the perceptual evaluation. Perhaps Gabriels severe motor speech disorder made it difficult for the listeners to understand him? Low agreement between listeners was a problem, however, and it was interesting to note that the parents of both the boys said they understood them better following the EPG. Rating of intelligibility in connected speech may have been more revealing. As EPG records and displays details of the tongue-palate contact during continuous speech, it provides new insight into articulatory patterns. This is important for a range of clients where traditional treatment techniques have failed. It also enabled our participants to learn where to place their tongues, something that other speech and language therapy had failed to achieve. Many parts of speech and articulation can be difficult for therapists to explain or raise awareness about, as the differences in

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to the parents, who gave consent for publication of their childrens case reports. We also want to express our gratitude to Professor Fiona Gibbon, Queen Margaret University College, Edinburgh, UK and Per Lindblad, Senior Lecturer at the University of Lund, Sweden, for exquisite advice and guidance. The present research was financially supported by grants from the Research Council of Disability Administration, Region Vastra SLTP Gotaland, Sweden.

References

Gibbon, F. & Wood, S. (2003) Using electropalatography (EPG) to diagnose and treat articulation disorders associated with mild cerebral palsy: a case study, Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 17, pp.365-374. Hardcastle, W., Gibbon, F. & Jones W. (1991) Visual display of tongue-palate contact: electropalatography in the assessment and remediation of speech disorders, British Journal of Disorders of Speech Communication 26, pp.41-74. Hardy, J.C. (1983) Cerebral Palsy. Englewood cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Hellquist, B. (1982) SIT- Sprkligt Impressivt Test fr barn (Language Comprehension Test for Children) (Malm: Tryckeriteknik). World Health Organisation (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO. Lohmander, A., Borell, E., Henningsson, G., Havstam, C,. Lundeborg, I. and Persson, C. (2005) Swedish Articulation and Nasality Test. Pedagogisk Design, www.dop.se Pennington, L., Goldbart, J. and Marshall J. (2005) Direct speech and language therapy for children with cerebral palsy: findings from a systematic review, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 47, pp.57-63. Strand, E.A., (1995) Treatment of motor speech disorders in children, Seminars in Speech and language, 2, pp.126-139. 26

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2008

REFLECTIONS DO I FACILITATE AND REACH AGREEMENT ON REALISTIC LEVELS OF HOME PRACTICE? DO I SEEK WAYS OF CAPTURING SMALL CHANGES IN THE DIRECTION OF A TARGET? DO I USE A VARIETY OF METHODS TO ASSESS THE IMPACT OF THERAPY ON INTELLIGIBILITY?

What questions does this article raise for you? Have you been able to access Electropalatography for any of your clients? Let us know via the Winter 08 forum at http://members.speechmag. com/forum/

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Mount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Document78 paginiMount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Speech & Language Therapy in Practice75% (8)

- Talking Mats: Speech and Language Research in PracticeDocument4 paginiTalking Mats: Speech and Language Research in PracticeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imprints of The MindDocument5 paginiImprints of The MindSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phoneme isolation constraints in Dutch kindergartnersDocument17 paginiPhoneme isolation constraints in Dutch kindergartnersboufriss0% (1)

- In Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Truth Behind The Polio VaccineDocument28 paginiThe Truth Behind The Polio VaccineFreedomFighter32100% (2)

- Turning On The SpotlightDocument6 paginiTurning On The SpotlightSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhalaaji - Art and Science of Orthodontics WordDocument578 paginiBhalaaji - Art and Science of Orthodontics WordBudi AthAnza Suhartono85% (13)

- Prioritization of ProblemsDocument8 paginiPrioritization of ProblemsFirenze Fil100% (3)

- NP4 Nursing Board Exam NotesDocument9 paginiNP4 Nursing Board Exam NotesNewb TobikkoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kent Academic Repository: Full Text Document PDFDocument6 paginiKent Academic Repository: Full Text Document PDFismail39 orthoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sleeping Newborns Extract Prosody From Continuous SpeechDocument10 paginiSleeping Newborns Extract Prosody From Continuous SpeechsoypochtecaÎncă nu există evaluări

- U7_The acquistion of phonologyDocument8 paginiU7_The acquistion of phonologycosmindudu1980Încă nu există evaluări

- Saloranta 2020Document11 paginiSaloranta 2020Isadora BardotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nordgren 2014Document27 paginiNordgren 2014Bianca PintoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speech Summer Camp For Treating Articulation Disorders in Cleft Palate PatientsDocument9 paginiSpeech Summer Camp For Treating Articulation Disorders in Cleft Palate PatientsFernanda PugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solution Manual For Communication Disorders Casebook The Learning by Example 0205610129Document4 paginiSolution Manual For Communication Disorders Casebook The Learning by Example 0205610129Gregory Robinson100% (29)

- W ' E O M T ?: HAT S The Vidence For RAL Otor HerapyDocument2 paginiW ' E O M T ?: HAT S The Vidence For RAL Otor HerapyAdrian UluÎncă nu există evaluări

- How - . - I Use Therapeutic Listening.Document5 paginiHow - . - I Use Therapeutic Listening.Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Working Memory and Novel Word Learning in Children With HI & SLIDocument22 paginiWorking Memory and Novel Word Learning in Children With HI & SLIBayazid AhamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Efficacy of Auditory Training Using The Auditory Brainstem Response To Complex Sounds: Auditory Processing Disorder and Specific Language ImpairmentDocument10 paginiEfficacy of Auditory Training Using The Auditory Brainstem Response To Complex Sounds: Auditory Processing Disorder and Specific Language ImpairmentClau MarínÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discusion ClaseLenguajeDocument11 paginiDiscusion ClaseLenguajealbertonoquieroÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Words, The Mental Lexicon, Speech ProductionDocument34 paginiFirst Words, The Mental Lexicon, Speech ProductionJázminÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chewing Technique in Phonation of SLP StudentsDocument5 paginiChewing Technique in Phonation of SLP Studentsmajid mirzaeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABER Assessment in Pre-School Children with DLDDocument3 paginiABER Assessment in Pre-School Children with DLDlourdwsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Húngaros - TEL y Priming RutmoDocument12 paginiHúngaros - TEL y Priming RutmoMarce MazzucchelliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018, Immature Auditory Evoked Potentials in Children With Moderate-Severe Developmental Language DisorderDocument13 pagini2018, Immature Auditory Evoked Potentials in Children With Moderate-Severe Developmental Language DisorderLaisy LimeiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cochlear Implant Study Examines Children's Language SkillsDocument15 paginiCochlear Implant Study Examines Children's Language SkillsHafidz Triantoro Aji PratomoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children Lose The Ability To Hear The Sounds of An L2 at Around One Year of Age: The Implications For Teachers of Young Learners of EnglishDocument8 paginiChildren Lose The Ability To Hear The Sounds of An L2 at Around One Year of Age: The Implications For Teachers of Young Learners of Englishjim jensenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bettcher Apsy 652 Term PaperDocument13 paginiBettcher Apsy 652 Term Paperapi-162509150Încă nu există evaluări

- Casal 2002Document11 paginiCasal 2002Niryireth CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kiese HimmelDocument9 paginiKiese HimmelhassaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Current_Trends_in_Medicine_and_Medical_RDocument7 paginiCurrent_Trends_in_Medicine_and_Medical_RJunior KabeyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- May Et Al 2012 LG and The Newborn BrainDocument9 paginiMay Et Al 2012 LG and The Newborn BrainFer CRÎncă nu există evaluări

- LD Final Exam PaperDocument8 paginiLD Final Exam Paperapi-709202309Încă nu există evaluări

- HyperarticulationofVowels Utheretal2012Document7 paginiHyperarticulationofVowels Utheretal2012Carolina RochaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hearing Thresholds in Young Children With and Without Cleft PalateDocument8 paginiHearing Thresholds in Young Children With and Without Cleft PalatePutra WaspadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- JOFFE-2012 Phon TherapyDocument50 paginiJOFFE-2012 Phon TherapyMaria P12Încă nu există evaluări

- Articulo Disartria y Paralisis CerebralDocument6 paginiArticulo Disartria y Paralisis CerebralHaizea MuñozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Portfolio1 - NormoyleDocument5 paginiPortfolio1 - Normoyleapi-317381538Încă nu există evaluări

- Lalain Nguyen HabibDocument4 paginiLalain Nguyen HabibMichel HabibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stage 5 PDFDocument16 paginiStage 5 PDFkakaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question About How Children Get Language AcquisitionDocument2 paginiQuestion About How Children Get Language AcquisitionIhhaver Glory100% (1)

- Effect of Shadowing Training On Phonological Awareness Development: Difference Between Auditory-Sequential Learners and Visual-Spatial LearnersDocument4 paginiEffect of Shadowing Training On Phonological Awareness Development: Difference Between Auditory-Sequential Learners and Visual-Spatial LearnersAhmad A. JawadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articulo Disartria y Paralisis CerebralDocument10 paginiArticulo Disartria y Paralisis CerebralHaizea MuñozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gather Cole 1993Document14 paginiGather Cole 1993HocvienMAEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children With SLI May Look Less at Talker's MouthDocument13 paginiChildren With SLI May Look Less at Talker's MouthPaul AsturbiarisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Affecting Stimulability of Erred Sounds inDocument7 paginiFactors Affecting Stimulability of Erred Sounds inLaurentiu Marian MihailaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Botting Conti-Ramsden 2001Document13 paginiBotting Conti-Ramsden 2001Gaby HerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article 1 89 enDocument7 paginiArticle 1 89 enEsraa EldadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive performance and perceived effort in speech processing tasks with normal and hearing impaired subjects in different noise backgroundsDocument13 paginiCognitive performance and perceived effort in speech processing tasks with normal and hearing impaired subjects in different noise backgroundsNatalia Belen Medina GarridoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intensive Speech Therapy in Ugandan Patients With Cleft (Lip And) Palate ADocument12 paginiIntensive Speech Therapy in Ugandan Patients With Cleft (Lip And) Palate Acvdk8dc8sbÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Causes of Specific Developmental LanguageDocument9 paginiThe Causes of Specific Developmental LanguageAndresSalasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated Bibliography Template MaxDocument8 paginiAnnotated Bibliography Template MaxNaomi BerkovitsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Isabelle Rapin (1996) - Practitioner Review. Developmental Language Disorders. A Clinical Update.Document14 paginiIsabelle Rapin (1996) - Practitioner Review. Developmental Language Disorders. A Clinical Update.Geraldine BortÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment Repetitive Language in Kids Suffering From Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument8 paginiAssignment Repetitive Language in Kids Suffering From Autism Spectrum Disordermadelein garciasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apraxia and Verbal Dyspraxia For Educators: Accommodations in The ClassroomDocument12 paginiApraxia and Verbal Dyspraxia For Educators: Accommodations in The Classroomapi-584896872Încă nu există evaluări

- WolkandBrennan PhonoInvestigationAutism 2013Document9 paginiWolkandBrennan PhonoInvestigationAutism 2013Aiman rosdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Mss Usha Final Management Cleft ConDocument6 pagini4 Mss Usha Final Management Cleft ConAnurag SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aural Impairment (Types and Causes) :: Causes of Hearing ImpairmentsDocument4 paginiAural Impairment (Types and Causes) :: Causes of Hearing Impairmentsroselin sahayamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Review: Effects of Mild To Moderate Sensorineural Hearing Loss On The Language Development of School Aged ChildrenDocument5 paginiCritical Review: Effects of Mild To Moderate Sensorineural Hearing Loss On The Language Development of School Aged ChildrenErsya MusLih AnshoriÎncă nu există evaluări

- WolkandBrennan PhonoInvestigationAutism 2013Document9 paginiWolkandBrennan PhonoInvestigationAutism 2013ALEXANDRE BARBOSAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaika T S NewDocument2 paginiAnaika T S NewHarikrishnan P CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auditory Symptoms and Psychological Characteristics in Adults With Auditory Processing DisordersDocument6 paginiAuditory Symptoms and Psychological Characteristics in Adults With Auditory Processing DisordersBagoes AsÎncă nu există evaluări

- ProjectDocument12 paginiProjectapi-711088465Încă nu există evaluări

- Al-Salim Non-Word DeafDocument13 paginiAl-Salim Non-Word DeafAriana MondacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Down syndrome phonologyDocument9 paginiDown syndrome phonologyGerome ManantanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speech DefectDocument4 paginiSpeech Defectnali.Încă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One SPR 09 Friendship ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One SPR 09 Friendship ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Summer 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Summer 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Document1 paginăIn Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Winter 2007)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Winter 2007)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 09) Speed of SoundDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 09) Speed of SoundSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Autumn 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Autumn 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowDocument1 paginăHere's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 10) Acknowledgement, Accessibility, Direct TherapyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 10) Acknowledgement, Accessibility, Direct TherapySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Aut 09 Communication Tree, What On EarthDocument1 paginăHere's One Aut 09 Communication Tree, What On EarthSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ylvisaker HandoutDocument20 paginiYlvisaker HandoutSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Document2 paginiIn Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Summer 10Document1 paginăHere's One Summer 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Winter 10Document1 paginăHere's One Winter 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 11Document1 paginăHere's One Spring 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalDocument2 paginiIn Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applying Choices and PossibilitiesDocument3 paginiApplying Choices and PossibilitiesSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boundary Issues (7) : Drawing The LineDocument1 paginăBoundary Issues (7) : Drawing The LineSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practical FocusDocument2 paginiA Practical FocusSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applied PalynologyDocument2 paginiApplied PalynologySanjoy NingthoujamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Report VTDocument12 paginiCase Report VTAnonymous ZbhBxeEVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full HD English Editorials 2-1-2022Document25 paginiFull HD English Editorials 2-1-2022uihuyhyubuhbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Round Cell Tumors - Classification and ImmunohistochemistryDocument13 paginiRound Cell Tumors - Classification and ImmunohistochemistryRuth SalazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- MiconazoleDocument3 paginiMiconazoleapi-3797941Încă nu există evaluări

- Gluten Free Marketing Program - OUTLINEDocument8 paginiGluten Free Marketing Program - OUTLINEslipperinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1B Cytokine Instruction Manual-10014905CDocument52 pagini1B Cytokine Instruction Manual-10014905CJose EstrellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (English) About Your Heart Attack - Nucleus Health (DownSub - Com)Document2 pagini(English) About Your Heart Attack - Nucleus Health (DownSub - Com)Ken Brian NasolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pariet Tablets: ® Product InformationDocument12 paginiPariet Tablets: ® Product InformationSubrata RoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Somatic Cell Count and Type of Intramammary Infection Impacts Fertility in Vitro Produced Embryo TransferDocument6 paginiSomatic Cell Count and Type of Intramammary Infection Impacts Fertility in Vitro Produced Embryo TransferalineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsDocument5 paginiDiabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsPetra Diansari ZegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carbohydrates Clinical SignificanceDocument10 paginiCarbohydrates Clinical SignificanceMay Ann EnoserioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biological Psychiatry: Is There Any Other KindDocument9 paginiBiological Psychiatry: Is There Any Other KindLiam Jacque LapuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dickens and Bio Politics. ArticleDocument24 paginiDickens and Bio Politics. ArticleJose Luis FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 30802Document16 pagini30802YAMINIPRIYANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On Sweet PotatoDocument7 paginiResearch Paper On Sweet Potatoafeawldza100% (1)

- Essay in MapehDocument4 paginiEssay in MapehJane Ikan AlmeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Snow White - Abnormal Psychology PaperDocument6 paginiSnow White - Abnormal Psychology PaperNicky JosephÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oral Myiasis PublicationDocument6 paginiOral Myiasis PublicationAnkita GoklaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surgical Treatment of Tarsal Coalitions in ChildrenDocument10 paginiSurgical Treatment of Tarsal Coalitions in ChildrenNegru TeodorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Necrotizing PancreatitisDocument37 paginiAcute Necrotizing PancreatitisVania SuSanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cara Hitung MPAP, CO, dan Penilaian Regurgitasi dan Stenosis Valve JantungDocument6 paginiCara Hitung MPAP, CO, dan Penilaian Regurgitasi dan Stenosis Valve JantungwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- AlkaloidsDocument21 paginiAlkaloidssanjiv_m20100% (1)

- Occupational Safety and Health (Osh) Management HRM3033: Topic 2: Accident TheoriesDocument31 paginiOccupational Safety and Health (Osh) Management HRM3033: Topic 2: Accident TheoriesNurulFatihah01Încă nu există evaluări

- Single Vs Multiple Visits in PulpectomyDocument7 paginiSingle Vs Multiple Visits in PulpectomyHudh HudÎncă nu există evaluări