Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

TasNat 1911 No2 Vol4 pp69-70 Rodway NotesPlantClassification PDF

Încărcat de

President - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

TasNat 1911 No2 Vol4 pp69-70 Rodway NotesPlantClassification PDF

Încărcat de

President - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

TH E

TASMANIAN

NATURALIST.

Dotes on plant Classification

Bv L. RODWA Y (Government Botanist).

11.

!l that its leaves are relatively large and often much divided. It is not at all unusual to find people calling the deadly hemlock a fern and growing it in a garden, simply because it looks like one. This is an unfortunate mistake, and sometimes results in the death of a cow, which is inconvenient. For this reason alone, it is well to know what really is a fern. Besides, a naturalist should have some better reason for saying what is a fern, and what not, than general resemblance. We should note, firstly, that a fern never bears flowers and fruit. If a plant looking like a fern develops flowers, it belongs to the group of flowering plants and not to the ferns. This brings us to an important detail. Plants may vary extraordinarily in general appearance, but their method of producing is very constant. Each nat.ural group has its own method, and by it we know them. The result of profound study and research for many generations has led to this conclusion-that if we wish to group plants according to their true relationship, we must overlook general appearance, and pay attention to their modes of reproduction. If you examine the leaves of a fern you will find-at least upon some of them, situated upon the back, or close to the margin, or in others in little pockets-brown markings, which can readily be seen to be of a powdery nature. If some of this powder be removed and examined by the aid of a strong lens, or better still, under a microscope, it will be found to consist of beautiful little bags, each one full of spores. These bags are called sporangia, and it is as well to remember this name, for its use will be very necessary in our papers on other groups of plants. Well, a fern is a plant that bears numerous sporangia upon relatiyely large leaves. Because ferns bear sporangia upon their leaves, it was once considered that these organs were something more than leaves, and they were calle::l fronds. This is now pretty generally abandoned, and the name frond is only used for bodies which may be leaflike but are not leaves, as, for instance, the expansions of many seaweeds. When these sporangia are ripe, and weather conditions are favorable, they burst and scatter their spores. These bodies being very small are carried often to some distance by currents of air. Now comes an important feature in the Ii fe-history of a fern. When a spore finds itself in suitable conditions it germinates, but instead of growing into a fern like the one from which it arrived, it assumes a different state altogether. It grows into a little flat green plate, generally heartshaped, and seldom a quarter of an inch long. This it would be most unwise to call a fern ; it has received the name of a prothallium. In any conservatory where ferns grow these little prothallia may be found in quantity on damp

THE common way in which a fern is often recognised is by observing

FERNS.

70

THE TASMANIAN

NATURALIST

bricks, flower-pots, wet tree-fern stumps, and such like place. You must 110t be too hasty in finding prothallia; for all conservatories are infested with a flat, pale green liverwort, Lunularia, which may be mistaken for them. In Lunularia the substance is not very thin, is pale green, and dotted with minute white spots; prothalIia are very delicate, and darker. When a prothallium has reached sufficient age it develops on the under surface the essential organs of reproduction, the antheridia and archegonia. The archegonia should be understood, as we shail require to refer to them again. An archegonium is a flask-shaped thing containing a single little body destined to become an egg. In prothallia of ferns the archegonia are sunk in its substance. When one of the eggs has become fertilised all further development of the prothallium ceases, and the whole available energy is turned to develop the embryo. This embryo now grows into a fern like the one from which the spore was shed. This alternation of fern and prothallium always continues, and is commonly spoken of as the alternation of generation The fern only bears spores, and is the spore-bearing generation or sporophyte; the prothaUium only bears sexual organs, and is the sexual generation or gametophyte. These names also it is desirable to remember for future use. Here we have a rough life-history. Not only do ferns bear many s(.Jorangia on large leaves, but they live two independent existences, of which the sporophyte is the more important. In dealing with other groups of plants we shall meet with the same details only under various modifications. The sporangium is an organ old as the hills, and far older. It appeared first in almost the most primitive of plants-to run through the whole series of groups, even to the modern flowering plants. Howp.ver it may be modified and thrust about to different parts of a plant, it is always truly the same. Archegonia are not of so ancient a lineage, and do not extend to the highest group, but they first appear in a primitive condition in some algre, extend through mosses, ferns, Iycopods to coni fen, after which they vanish. The alternation of generations is also far-reaching. It appears at least in the red sea-weeds, and may be traced right through the other groups to the flowering plants Further details will be enlarged upon when we discuss other groups.

Rn elementary Review of marine Jnvert.brate Hnimals

(For Young Students)

Bv T. THOMPSON FLYNN, RSc.

IVING things as a whole are grouped into one or other of two .,. great kingdoms; one including animals, the other, plants. As we :see them in the higher forms, these are easily distinguished from one

It

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Rust, Smut, Mildew, & Mould: An Introduction to the Study of Microscopic FungiDe la EverandRust, Smut, Mildew, & Mould: An Introduction to the Study of Microscopic FungiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seedless Wonder of The Ancient: Lyle Kenneth Geraldez 10 - PhotonDocument2 paginiSeedless Wonder of The Ancient: Lyle Kenneth Geraldez 10 - PhotonLyle Kenneth GeraldezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advacned BotanyDocument26 paginiAdvacned Botanynoel edwin laboreÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1910 No2 Vol3 pp51-53 Rodway NotesPlantClassification PDFDocument3 paginiTasNat 1910 No2 Vol3 pp51-53 Rodway NotesPlantClassification PDFPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advacned BotanyDocument26 paginiAdvacned Botanynoel edwin laboreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Walking Tour PDFDocument8 paginiWalking Tour PDFavubnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Are Ferns in Most New ZealandersDocument45 paginiThere Are Ferns in Most New ZealandersMudjaijah draÎncă nu există evaluări

- E Que 11Document5 paginiE Que 11BillQueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes On Pteridophytes - 113258Document6 paginiNotes On Pteridophytes - 113258Borisade Tolulope VictorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vegetable Parasitos yDocument18 paginiVegetable Parasitos yramongonzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crow William Bernard The Occult Properties of Herbs and Plants (1969) 44p TextDocument44 paginiCrow William Bernard The Occult Properties of Herbs and Plants (1969) 44p TextNeil50% (2)

- Crow William Bernard - The Occult Properties of Herbs and Plants PDFDocument62 paginiCrow William Bernard - The Occult Properties of Herbs and Plants PDFMarzio FarulfR Venuti Mazzi100% (2)

- Division Bryophyta PDFDocument29 paginiDivision Bryophyta PDFPee BeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diversity in The Plant KingdomDocument14 paginiDiversity in The Plant KingdomJimmy Serendip100% (1)

- Quiver Trees, Phantom Orchids & Rock Splitters: The Remarkable Survival Strategies of PlantsDe la EverandQuiver Trees, Phantom Orchids & Rock Splitters: The Remarkable Survival Strategies of PlantsEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (2)

- Characteristics of Various PlantsDocument8 paginiCharacteristics of Various PlantsSakshi TewariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biology Non-Vascular PlantsDocument15 paginiBiology Non-Vascular PlantsVian choiÎncă nu există evaluări

- FernDocument29 paginiFernMazlina NinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- All About Ferns: A Resource Guide: What Makes A Fern A Fern?Document7 paginiAll About Ferns: A Resource Guide: What Makes A Fern A Fern?Gamer goÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Kingdom ClassificationDocument36 pagini5 Kingdom ClassificationMichelle Arienza100% (2)

- Class 11 Chapter 3 BryophytesDocument6 paginiClass 11 Chapter 3 BryophytesAshok KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- PlantsDocument93 paginiPlantsnehmiryll sumaletÎncă nu există evaluări

- BOT HW Chapter 20Document5 paginiBOT HW Chapter 20albelqinÎncă nu există evaluări

- PP9 Biodiversity of Plants 1453879364Document93 paginiPP9 Biodiversity of Plants 1453879364khijogpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carnivorous PlantDocument16 paginiCarnivorous PlantFrancois GarryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Incredible World of Plants - Cool Facts You Need to Know - Nature for Kids | Children's Nature BooksDe la EverandThe Incredible World of Plants - Cool Facts You Need to Know - Nature for Kids | Children's Nature BooksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 5 BOT1LDocument6 paginiChapter 5 BOT1LLovely BalambanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Botany HorsetailDocument3 paginiBotany HorsetailJohn Kevin NocheÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Occult Properties of Herbs 0850300363Document66 paginiThe Occult Properties of Herbs 0850300363Pouya Jahani0% (1)

- Plant DiversityDocument42 paginiPlant DiversityMehak BalochÎncă nu există evaluări

- Army Public School Gopalpur: Class 11 Science Subject - BiologyDocument6 paginiArmy Public School Gopalpur: Class 11 Science Subject - BiologyAshok KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- BOTANYDocument5 paginiBOTANYPrincess Fay LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allen, Grant. The Colours of FlowersDocument129 paginiAllen, Grant. The Colours of Flowersshelfedge100% (2)

- Classification of MossesDocument32 paginiClassification of MossesMuthiaranifs86% (7)

- Elementary Mycology 1Document7 paginiElementary Mycology 1AmaterasuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vallespin, Stem 12-20Document30 paginiVallespin, Stem 12-20vimvim vallespinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Exotic Rainforest: Zamioculcas ZamiifoliaDocument15 paginiThe Exotic Rainforest: Zamioculcas ZamiifoliabawadeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment D in BotanyDocument5 paginiAssignment D in BotanyChrizanne Irah TagleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Target Questions Basic BiologyDocument30 paginiTarget Questions Basic BiologyPolee SheaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plantclassification 120808061114 Phpapp02Document31 paginiPlantclassification 120808061114 Phpapp02Sendaydiego Rainne GzavinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Do Plants Eat Meat? The Wonderful World of Carnivorous Plants - Biology Books for Kids | Children's Biology BooksDe la EverandDo Plants Eat Meat? The Wonderful World of Carnivorous Plants - Biology Books for Kids | Children's Biology BooksÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Secret Life of Plants: A Fascinating Account of the Physical, Emotional, and Spiritual Relations Between Plants and ManDe la EverandThe Secret Life of Plants: A Fascinating Account of the Physical, Emotional, and Spiritual Relations Between Plants and ManEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (111)

- PP9 Biodiversity of PlantsDocument93 paginiPP9 Biodiversity of PlantsRorisang MotsamaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marsilea Crenata: PteridophyteDocument9 paginiMarsilea Crenata: PteridophyteNur Rezki OctaviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab 4 Land Plants IDocument12 paginiLab 4 Land Plants ILa Shawn SpencerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Botany Assignment - Chapter 20Document9 paginiBotany Assignment - Chapter 20FrancineAntoinetteGonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Notes - Bryophyte Training Day For RangersDocument13 paginiCourse Notes - Bryophyte Training Day For RangersMartin HindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diversity and Floristics of Monocots: - . - Aroids, Lilies, Orchids - .Document66 paginiDiversity and Floristics of Monocots: - . - Aroids, Lilies, Orchids - .Rifqi Fathul ArroisiÎncă nu există evaluări

- July 2009 Along The Boardwalk Newsletter Corkscrew Swamp SanctuaryDocument3 paginiJuly 2009 Along The Boardwalk Newsletter Corkscrew Swamp SanctuaryCorkscrew Swamp SanctuaryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lower Vascular PlantsDocument7 paginiLower Vascular PlantsNicaRejusoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genus NepenthesDocument7 paginiGenus Nepentheslenra AguirangÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 Pp16 Anon NatureStudySchoolsDocument1 paginăTasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 Pp16 Anon NatureStudySchoolsPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 Pp2-5 Crowther TasNatHistInterestingAspectsDocument4 paginiTasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 Pp2-5 Crowther TasNatHistInterestingAspectsPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat - 1928 - Vol2 - No4 - pp9-10 - Lord - Value of The PloverDocument2 paginiTasNat - 1928 - Vol2 - No4 - pp9-10 - Lord - Value of The PloverPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 WholeIssueDocument16 paginiTasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 WholeIssuePresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 Pp8-9 Lord IntroducedTroutDocument2 paginiTasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 Pp8-9 Lord IntroducedTroutPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 Pp14-16 Anon MoultingLagoonDocument3 paginiTasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 Pp14-16 Anon MoultingLagoonPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 WholeIssueDocument16 paginiTasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 WholeIssuePresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1926 Vol1 No5 Pp13-16 Reynolds TasmanianNaturalistsDocument4 paginiTasNat 1926 Vol1 No5 Pp13-16 Reynolds TasmanianNaturalistsPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 pp1 Anon ClubNotesDocument1 paginăTasNat 1928 Vol2 No4 pp1 Anon ClubNotesPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 Pp9-14 Lewis OutlinesGeologyDocument6 paginiTasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 Pp9-14 Lewis OutlinesGeologyPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 Pp4-9 CrowtherPChairmansAddressDocument6 paginiTasNat 1927 Vol2 No3 Pp4-9 CrowtherPChairmansAddressPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1927 Vol2 No2 pp1 Anon ClubNotesDocument1 paginăTasNat 1927 Vol2 No2 pp1 Anon ClubNotesPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1926 Vol2 No1 Pp8-16 Lewis OutlinesGeologyDocument9 paginiTasNat 1926 Vol2 No1 Pp8-16 Lewis OutlinesGeologyPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1926 Vol2 No1 Pp3-6 Crowther ChairmansAddressDocument4 paginiTasNat 1926 Vol2 No1 Pp3-6 Crowther ChairmansAddressPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1926 Vol2 No1 pp1-2 Anon ClubNotesDocument2 paginiTasNat 1926 Vol2 No1 pp1-2 Anon ClubNotesPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1926 Vol1 No5 WholeIssueDocument16 paginiTasNat 1926 Vol1 No5 WholeIssuePresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1926 Vol1 No5 Pp1-6 Livingstone ExcursionPortDaveyDocument6 paginiTasNat 1926 Vol1 No5 Pp1-6 Livingstone ExcursionPortDaveyPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp14 Rodway MilliganiaLindonianaDocument1 paginăTasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp14 Rodway MilliganiaLindonianaPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 No1 Vol3 WholeIssueDocument14 paginiTasNat 1925 No1 Vol3 WholeIssuePresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp15-16 Reynolds TasmanianNaturalistsDocument2 paginiTasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp15-16 Reynolds TasmanianNaturalistsPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Some Notes The " Watile " or " Acacia"Document3 paginiSome Notes The " Watile " or " Acacia"President - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 No1 Vol2 Pp1-9 Lewis OutlinesGeologyDocument9 paginiTasNat 1925 No1 Vol2 Pp1-9 Lewis OutlinesGeologyPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Some Notes The" Wattle" or " Acacia"Document3 paginiSome Notes The" Wattle" or " Acacia"President - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp13-14 Breaden BushRambleDocument2 paginiTasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp13-14 Breaden BushRamblePresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp10-11 Sharland LifeSwallowDocument2 paginiTasNat 1925 Vol1 No4 Pp10-11 Sharland LifeSwallowPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 No1 Vol2 Pp11-14 Harris NotesScottsdaleDocument4 paginiTasNat 1925 No1 Vol2 Pp11-14 Harris NotesScottsdalePresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- TasNat 1925 No1 Vol3 Pp1-11 Lewis OutlinesGeologyDocument11 paginiTasNat 1925 No1 Vol3 Pp1-11 Lewis OutlinesGeologyPresident - Tasmanian Field Naturalists ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inherited Change and Evolution-Topic 6Document20 paginiInherited Change and Evolution-Topic 6Kundiso NakomaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Answer Sheet in Science 7 Quarter 2 - Week 5 Module 14: Maya-Maya ST., Kaunlaran Village, Longos Malabon CityDocument2 paginiAnswer Sheet in Science 7 Quarter 2 - Week 5 Module 14: Maya-Maya ST., Kaunlaran Village, Longos Malabon CityHÎncă nu există evaluări

- LECTURE 19 Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseDocument7 paginiLECTURE 19 Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseCharisse Angelica MacedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plant Life CycleDocument4 paginiPlant Life CycleStefania Sierra MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2.3.1 Family PlanningDocument36 pagini2.3.1 Family PlanningLive with CjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Embriogenesis Ikan Betok Anabas Testudineus Pada Suhu Inkubasi Yang Berbeda PDFDocument75 paginiEmbriogenesis Ikan Betok Anabas Testudineus Pada Suhu Inkubasi Yang Berbeda PDFUcupJenggotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structure of Ovule and TypesDocument10 paginiStructure of Ovule and TypesJemson KhundongbamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tissue CultureDocument18 paginiTissue CultureRitesh DassÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Science of Seduction 2012 EbookDocument114 paginiThe Science of Seduction 2012 EbookNathan TambunanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproduction in Plants G7 SDocument37 paginiReproduction in Plants G7 Sgeorgy shibuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bartlett, ExperimentsDocument19 paginiBartlett, ExperimentsMaria TountaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genome Resource BanksDocument20 paginiGenome Resource BanksFernanda GouveaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Influencing Species SurvivalDocument14 paginiFactors Influencing Species SurvivaldevoydouglasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Esolutions Manual - Powered by CogneroDocument23 paginiEsolutions Manual - Powered by CogneroasdasdasdasdasdÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4th Form Biology Pretest 1revDocument4 pagini4th Form Biology Pretest 1revLynda BarrowÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8-Production of HaploidsDocument23 pagini8-Production of HaploidsvishalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Risk Factor For Preterm BirthDocument22 paginiClinical Risk Factor For Preterm BirthGabyBffÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estros Cycle in DogsDocument3 paginiEstros Cycle in DogsnessimmounirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproduction in Plants and Animals WorksheetDocument11 paginiReproduction in Plants and Animals Worksheetkarishma mannarÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLL Demo Science 5Document4 paginiDLL Demo Science 5Marie Fe Jambaro75% (4)

- Human Reproductive SystemDocument4 paginiHuman Reproductive SystemJoseph CristianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizha Bery Putriani - 0804113662Document14 paginiRizha Bery Putriani - 0804113662Atan GarifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproductive Technologies in Farm AnimalsDocument347 paginiReproductive Technologies in Farm AnimalsClecio Henrique Limeira100% (1)

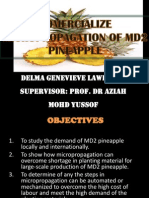

- Delma Genevieve Lawrence Supervisor: Prof. DR Aziah Mohd YussofDocument36 paginiDelma Genevieve Lawrence Supervisor: Prof. DR Aziah Mohd YussofRasyidah Miswandi100% (1)

- Menstrual CycleDocument18 paginiMenstrual CycleKim RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ectogenesis: Edited andDocument225 paginiEctogenesis: Edited andzhangxin liÎncă nu există evaluări

- HAP201 Reproductive 1 PDFDocument17 paginiHAP201 Reproductive 1 PDFkrissyÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBSE CBSE Class 10 Science Solved Question Paper 2015Document13 paginiCBSE CBSE Class 10 Science Solved Question Paper 2015s k kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBSE Class 12 Biology Question Paper 2020 Set 2Document6 paginiCBSE Class 12 Biology Question Paper 2020 Set 2Rajendra SolankiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aglaonema BreedingDocument8 paginiAglaonema BreedingJommel Perlas RevillaÎncă nu există evaluări