Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

How I Provide A Paediatric Dysphagia Service (1) : "Timely, Efficient, Integrated and Holistic"?

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

How I Provide A Paediatric Dysphagia Service (1) : "Timely, Efficient, Integrated and Holistic"?

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

HOW I

HOW I PROVIDE A PAEDIAT

WHEN PROVIDING SERVICES, SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPISTS HAVE TO FIND A BALANCE BETWEEN WHAT IS EFFICIENT AND PRACTICAL FOR STAFF AND WHAT IS MOST CONVENIENT AND HELPFUL TO CLIENTS AND FAMILIES. THIS IS PARTICULARLY THE CASE WHEN THE CLIENTS CONCERNED LIVE IN AREAS WHERE THE POPULATION IS SPREAD OUT AND HAVE LOWER INCIDENCE DIFFICULTIES REQUIRING A SPECIALISED, MULTI-AGENCY APPROACH. IN OUR SPRING 06 ISSUE, CHARLOTTE BUSWELL AND REBECCA HOWARTH EXPLORED DECISION MAKING IN PAEDIATRIC DYSPHAGIA. HERE, THE FOCUS MOVES TO THE ORGANISATIONAL LEVEL AS OUR TWO CONTRIBUTORS DESCRIBE HOW THEIR DIFFERENT PAEDIATRIC DYSPHAGIA SERVICES HAVE EVOLVED TO SUIT LOCAL NEED. ONE IS COMMUNITY-BASED, WHILE THE OTHER HOSPITAL-BASED SERVICE CROSSES THE ACUTE AND COMMUNITY SECTORS. PAEDIATRIC DYSPHAGIA (1) TIMELY, EFFICIENT, INTEGRATED AND HOLISTIC? PAEDIATRIC DYSPHAGIA (2) PARENTS AT THE CENTRE

HOW I (1):

Timely, efficient, integrated and holistic?

RCSLT CLINICAL GUIDELINES FOR DISORDERS OF FEEDING, EATING, DRINKING AND SWALLOWING STATE THAT SERVICES SHOULD BE TIMELY, EFFICIENT, INTEGRATED AND HOLISTIC (2005, P.63). JOANNA MANZ CONSIDERS HOW THE COMMUNITY PAEDIATRIC DYSPHAGIA SERVICE SHE HAS DEVELOPED IN A RURAL AREA MEASURES UP TO THIS BENCHMARK.

ngus is a rural area, with one specialist speech and language therapist providing assessment and treatment for pre-school and school age children who have eating and drinking difficulties. Although I work as a sole practitioner, I am able to access peer supervision from specialist speech and language therapy colleagues within Tayside, and am a member of a clinical network which has paediatric feeding as part of its remit. Within Angus, I was responsible for devising a care pathway which took account of limited capacity in terms of therapy time but also adhered to the Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists Clinical Guidelines (2005). These outline the management process for dysphagia, and reflect the breadth and complexity of assessment and intervention across various settings. The introduction refers to safety, nutrition and hydration as being of paramount consideration (p.63). As community dysphagia services take place in diverse settings, I found that careful planning was required to manage the risk involved as well as reflect the evidence base for intervention.

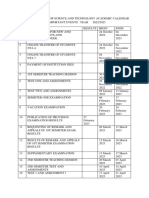

Having set up a service model, I wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of this pathway. This article describes the service and the outcomes for all cases referred over the two year period from July 2004-2006. It covers: 1. Number and source of referrals to the community service 2. Involvement of health visiting services 3. Multi-agency working 4. Intervention (and how it links with the current evidence base for dysphagia) 5. Outcomes in particular how well I had enabled parents and carers to manage their own childrens eating and drinking difficulties 6. Reflections and looking to the future. 1. Referrals Ages of the children are in table 1, and a breakdown for source of referrals in table 2. Among the pre-school population, reasons for referral fell into three categories: i. difficulties at the weaning stage of development ii. carer concern because of gagging and choking iii. failure to thrive as measured by health visitors on standard growth charts. The children of school age had significant physical and cognitive difficulties, with associated disorders of chewing and swallowing. Table 1 Ages of children at referral

Age: Number: 0-12 1-2 2-3 3-4 5 Children months years years years years at school 4 3 3 4 2 5

PRACTICAL POINTS: PAEDIATRIC DYSPHAGIA SERVICES

1. RECOGNISE THAT SERVICE DEVELOPMENT GIVES AN OPPORTUNITY FOR REFLECTION 2. AUDIT, QUESTION AND USE THE RESULTS TO ARGUE FOR CHANGE 3. ENSURE YOU HAVE ADEQUATE SUPERVISION AND ROBUST CLINICAL NETWORKS 4. MATCH THE LEVEL OF PROFESSIONAL INVOLVEMENT TO CLINICAL NEED 5. ARRANGE JOINT APPOINTMENTS WHERE POSSIBLE 6. CONSIDER HOW MUCH YOU CAN PROVIDE IN THE CLIENTS HOME 7. PREPARE THE GROUND SO YOU MAKE THE MOST OF THE AVAILABLE APPOINTMENT TIME 8. FOCUS ON EDUCATION AND EMPOWERMENT OF OTHERS 9. SIMPLE TOOLS (DIARIES, ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE) CAN BE VERY EFFECTIVE 10. OFFER FORMALISED FOLLOW-UP SUPPORT SUCH AS A HELPLINE

Table 2 Sources of referrals

Source Community paediatricians Health visitors Speech and language therapists Acute medical Education staff Number 9 6 3 2 1

24

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE Autumn 2007

HOW I

ATRIC DYSPHAGIA SERVICE

2. Involvement of health visiting services I decided joint visiting with the childs health visitor should be an integral part of the service, and I discussed this approach with community nurse managers. Health visitor colleagues consistently reported that they felt joint visiting was useful for information sharing, particularly about the childs feeding and early developmental history. We found that the childs carer also benefited as it saved time and avoided duplication of the information they had to convey at the initial assessment. Of the 21 children referred, 13 were seen jointly for initial assessment. The remaining children included 5 who were in school. For the other 3 we had to rely on phone contact, as our workloads meant joint visiting proved too difficult. 3. Multi-agency working Community dysphagia services do not have the support in terms of human resources and physical structures which characterises services within the acute sector. In their 2002 article about adult dysphagia management, Armstrong and Pendlowski conclude, there are some fundamental differences in dysphagia service delivery in a rural area. Some of the differences they describe include the location of intervention not being within the confines of an acute hospital setting and the challenges of working in community teams. These factors are relevant in service delivery to children and families in their homes and school settings. To manage the risks to children appropriately, I rely on robust multi-agency - as well as multi-disciplinary team - working. This includes ensuring regular contact times and telephone / e-mail liaison. The community team across Angus incorporates health visitors, a community paediatric dietician, community paediatricians, teachers and support workers in schools and nurseries and the carers of the children, and can also involve childminders and private provider nurseries. The new care pathway I implemented has multi-agency working as a central tenet (see magazine extras on www. speechmag.com). 4. Intervention Prior to assessment, I had a discussion with the relevant health visitor to get a detailed early feeding history. A joint visit could be set up at this time. For school-aged children, I contacted the staff and the childs carer prior to the assessment. Multi-disciplinary liaison is part of the pre-clinical evaluation, and is recognised as informing assessment methods (RCSLT, 2005). Following this I: made a telephone appointment with the carer to discuss what the home visit would involve. observed the child eating and drinking, and discussed what interventions would be useful. completed written advice within a week and sent it back to the carer. This was a summary of the discussion and advice given verbally during the home visit. followed up through telephone contact with both the carer and the health visitor, who could continue to support the carer during any routine visits. made a further visit if the carer required more specific input or had any concerns. sent a standard letter at 6 months to ask if the carer required further input. Although this article is not intended to describe intervention strategies in detail, I found the factors described under Preparation for oral intake (RCSLT, 2005, p.67) were of particular relevance. Modification of aspects such as positioning, environmental factors, presentation of foods and the childs appetite significantly affected eating and drinking skills. Changes in the way food was presented and the subsequent impact upon the childs oral skills led to positive outcomes for many of the children referred, including a twin well call Mark. Born at 36 weeks, Mark was referred by his health visitor because of concerns about choking and vomiting on firm foods. He was still being fed 8 month jars of baby food and his carer was anxious and unable to move Mark on to finger foods as he chokes with any lumps. Some early food refusal was emerging. Although he had good proximal (trunk) stability, Mark preferred to be fed on his carers knee. The health visitor reported no significant early feeding difficulties. Mark was bottle fed and at the time of referral was still taking milk from a bottle. Mark was not showing any independence in feeding. He had delayed oral-motor skills for chewing and was not yet starting to develop independent movement of tongue and jaw. He used a strong suckling pattern for thin pures. My recommendations included: Encourage food experimentation (play) in a non-nutritional context. Introduce very small amounts of bite and dissolve foods at a non-mealtime. Present these in Marks high chair. Time limit these sessions. (Presentation of food and drink, RCSLT 2005, p. 67) Encourage the use of teething rings and toys to help develop bite and oral exploration (Preparation for oral intake, RCSLT 2005, p.67). I also described to the carer the importance of independence, and the experience of firmer foods as vital to the development of chewing. The health visitor reported after six weeks that Mark was showing an interest in family foods and enjoying independent snacks in his high chair. The carer reported that he was choking less and vomiting had stopped altogether. The health visitor felt confident to continue with advice and monitoring as required. She would take forward the introduction of a non-lidded cup in the same way. Both she and the carer knew they could contact me at any time if the situation changed. Part of this process involved describing the development of normal patterns of eating and drinking. Carers frequently report that they find it useful to think of eating as a process rather than something which, as they had previously assumed, will happen automatically. Food play has been described as successful in developing positive attitudes to eating and drinking in children with severe failure to thrive (Masel and Franklin, 1996). 5. Outcomes Of the 20 children seen for assessment, 16 needed only the standard package of care described above with no further follow-up. This may reflect the fact that the process had allowed carers to become empowered to manage their own childs difficulties. There is evidence from work carried out with adult patients for the importance of managing feeding difficulties in the individuals home environment. Hotaling (1990) described improvements in attitudes to mealtimes and amounts of foods eaten when interventions took place in the persons home. The dysphagia guidelines (RCSLT, 2005, p.66) refer to the clients physical environment and social setting as being optimum for evaluation and intervention. I feel that the carers with whom I work have greater influence on the process of changing their childs feeding if input is set in their home context. With the support of a feeding specialist and health care practitioner, they can use mealtimes to develop awareness, appetite and enjoyment of foods. Working directly in the childs home ensures a holistic approach. Morris (1989) described the importance of sensori-motor organisation on development of swallowing skills. We are able to give practical advice on managing the environment to optimise this sensory organisation, and provide realistic advice which takes all the factors around mealtimes into account. Carers know they also have the safety net of being able to contact either the therapist or the health visitor with any concerns they have about the advice given. As the health visitor is well known to the child and carer, change in the feeding process is facilitated by this relationship. The RCSLT guidelines describe several articles which reflect a high evidence base for multidisciplinary management of individuals with dysphagia (2005, p.63). I feel that, within community services, the success or otherwise of a feeding intervention depends upon the above factors as well as the skills and experience of the feeding specialist. Of the remaining four cases, two had enduring maternal anxiety, which caused difficulties complying with advice given. For them, I recruited nursery staff and preschool home visiting services to assist with the ongoing programme; both childrens difficulties have resolved and they have been discharged from the service. Again, Armstrong and Pendlowski (2002) acknowledge the importance of this when describing their work in a rural area: We also rely on many different individuals to act as our proxies. Of the final two cases, one child was referred for videofluoroscopy and found to have a normal swallow. I gave advice to the parents on food presentation and pacing of mealtimes to reduce her coughing symptoms. The other child was a baby whose feeding was difficult because of substance withdrawal at birth. She required three follow-up visits before her feeding pattern settled. 6. Reflections Providing an effective service for children and their car-

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE Autumn 2007

25

HOW I

ers in home and education settings has been challenging. It has allowed me reflect on my role as a feeding specialist in many ways. An important part of my intervention is education, which has to take account of variables such as maternal anxiety (all the carers of the pre-school children reported feeling de-skilled by having their child referred for eating and drinking difficulties) and knowledge of normal eating and drinking. Increasing knowledge of the normal processes of eating and drinking can assist development of eating and drinking for children at risk of swallowing difficulties (Siktberg and Bantz, 1999). Education support workers and carers had close daily contact with the children with whom they worked, and had established ways of feeding children. The RCSLT guidelines (2005, p.70) state, Caregivers need to be able to facilitate optimally safe efficient and pleasurable eating and drinking. Working with carers and demonstrating techniques in their environment makes any intervention realistic and of practical benefit. Health visiting colleagues were able to form part of the assessment and treatment process with their expertise of feeding management.

I am working with the health visitor who is responsible for development of education within community nursing in Angus to provide written guidelines on feeding development, and guidance about when to refer to the speech and language therapy service. These will also form part of a training package to be delivered to public health nursing staff. This training will include: a. The development of eating and drinking b. The normal process of eating and drinking c. Causes of difficulty d. Guidance on how to help e. Referral pathway. I have found that through working closely with health visitors and education support workers they have gained a level of knowledge which allows them to maintain a feeding programme when I am not present. The above training will empower nursing colleagues in offering advice for families who are experiencing feeding problems, particularly at the weaning stage. My experience of providing a community service has taught me that flexibility of approach is vital. Safe and effective practice has to adapt to as many settings as there are children referred.

Joanna Manz is a Senior Specialist Speech and Language Therapist at Abbey Health Centre, East Abbey Street, Arbroath, Angus DD11 1EN, e-mail joanna.manz@nhs.net.

References

Armstrong, L. & Pendlowski, A. (2002) Twenty miles between clients, Bulletin of the Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists May. Hotaling, D. L. (1990) Adapting the mealtime environment: setting the stage for eating, Dysphagia. 5 (2) pp. 77-83. Masel, C. & Franklin, L. (1996) Management of Eating Difficulties in Children with Failure to Thrive, Australian Communication Quarterly Spring. Morris, S.E. (1989) Development of oral-motor skills of the neurologically impaired child, receiving non-oral feeding, Dysphagia 3 (3), pp. 135-54. Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists (2005) Clinical Guidelines. Bicester: Speechmark. Siktberg, I.L. & Bantz, D.L. (1999) Management of children with swallowing disorders, Journal of Paediatric SLTP Health Care 13 (5), pp. 223-9.

HOW I (2):

Parents at the centre

ROSEMARY PARKER CHARTS THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE TORBAY COMBINED FEEDING CLINIC FROM ITS CONCEPTION 12 YEARS AGO, VIA AN AUDIT TO A RECENT PARENTAL QUESTIONNAIRE, AND OUTLINES HER HOPES FOR ITS FUTURE.

he Paediatric Combined Feeding Clinic in Torbay has evolved over the last twelve years and is the first of its kind in the South West Peninsula. It was precipitated when, in addition to my role with children with complex communication and language difficulties, I began to receive rapidly increasing referrals for babies and young children with feeding problems; the legacy of modern technology is a cohort of infants who survive in spite of being born prematurely (Kennedy, 1997). These problems ranged from highly complex to relatively mild. At one end, there was an impaired ability to protect the airways and significantly compromised fluid / solid intake which required swift, informed decisions on total or partial nonoral feeding. At the other, were children with secondary behavioural difficulties arising from more subtle oromotor limitations and / or unrecognised sensory defensiveness who required a supported management plan. I was dealing with children suffering from failure to thrive, inadequate nutrition, frequent chest infections, compromised developmental progress (with its link to long-term health problems such as cardiovascular disease / diabetes mellitus), food avoidance and the effect on family dynamics and quality of life for child and carers. Families were being offered isolated advice which led to delayed

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE Autumn 2007

treatment, and there was inefficiency from the overlap of clinical input. Disproportionate time was spent on communication between disciplines and there were multiple appointments over an extended timescale for families.

The main functions of the clinic are to: Assess the problem and offer a plan Promote early identification and treatment Support parents and professionals Provide resource to other professionals Provide a link with other feeding teams. Our objectives are to: i. Enable safe feeding and adequate nutrition ii. Offer clear, realistic and achievable advice iii. Reduce parental anxiety / stress iv. Enable mealtimes to be more sociable v. Maximise consistency of approach across environments vi. Reduce appointments for both families and professionals. Our caseload covers children with neuromuscular difficulties, specific syndromes, prematurity, acquired or progressive conditions, craniofacial abnormalities, learning disability, cardiac / respiratory related difficulties and gastro oesophageal reflux. Their presenting problems include: Impaired swallow function Impaired co-ordination of suck breathe swallow synchrony Risk of aspiration safety issues Impaired oromotor function Texture / transition difficulty Difficulty with chewing / choking / vomiting Failure to thrive Reduced endurance Non-oral to supplementary to full oral feeding (and vice versa). There are exceptions however for: 1. Children under 3 years with purely behavioural and management problems. They are seen by the small,

Practical, realistic plan

The need for a holistic approach, with parents at the centre, was clear. Also apparent was the value of coordinated multi-professional advice to produce a practical, realistic plan, tailored to each individuals requirements - and so the Paediatric Combined Feeding Clinic was born. The specialist core team is in table 1. Table 1 Specialist Core Team

Consultant Paediatrician Dietitian Speech & Language Therapist (Coordinator) Occupational Therapist

Child & family

Plus individual others such as health visitors, physiotherapists, teachers

26

reprinted from www.speechmag.com

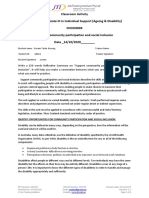

Care pathway for paediatric dysphagia, Angus (Joanna Manz, Autumn 07, pp.24-26)

Referral received

Discuss as per new guidelines

Discuss history Open file Arrange joint domiciliary visit Request eating/drinking be observed

Domiciliary visit Obtain feeding history Obtain relevant history from carer

NO

Observe eating/ drinking

Posture/seating Maternal/carer anxiety Childs response to mealtime Texture of food Utensils used Environmental distractions

Behaviour difficulty

NO

YES

Oro-motor control Texture tolerance hypersensitivity Development of chewing Development of independence Management of liquids Choking Food refusal hypersensitivity

Health visitor to resume management Discuss with carer

Liaise with Team Health visitor Community medical Acute medical Dietetics

Management Verbal advice Written advice Modify posture Modify texture Plan next visit

Discharge SLT input not appropriate Adequate oro-motor function Problem resolved Assess/advise only Maternal anxiety resolved Inadequate compliance

Write Report Client not at home Visit again

Evaluate Progress

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Mount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Document78 paginiMount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Speech & Language Therapy in Practice75% (8)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Sattler-Assessment of Children PDFDocument67 paginiSattler-Assessment of Children PDFTakashi Aoki100% (6)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Case Study 2Document2 paginiCase Study 2DUDUNG dudongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talking Mats: Speech and Language Research in PracticeDocument4 paginiTalking Mats: Speech and Language Research in PracticeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Big Five Personality Test - Truity MBA056 PDFDocument10 paginiThe Big Five Personality Test - Truity MBA056 PDFSaurav RathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ylvisaker HandoutDocument20 paginiYlvisaker HandoutSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practical FocusDocument2 paginiA Practical FocusSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test ResultDocument1 paginăTest ResultNicole AnahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mini Cog FormDocument2 paginiMini Cog FormAnonymous SVy8sOsvJDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Turning On The SpotlightDocument6 paginiTurning On The SpotlightSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Winter 2007)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Winter 2007)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imprints of The MindDocument5 paginiImprints of The MindSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowDocument1 paginăHere's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Autumn 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Autumn 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One SPR 09 Friendship ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One SPR 09 Friendship ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 09) Speed of SoundDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 09) Speed of SoundSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Summer 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Summer 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Document1 paginăIn Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Document2 paginiIn Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Aut 09 Communication Tree, What On EarthDocument1 paginăHere's One Aut 09 Communication Tree, What On EarthSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 10) Acknowledgement, Accessibility, Direct TherapyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 10) Acknowledgement, Accessibility, Direct TherapySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Winter 10Document1 paginăHere's One Winter 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalDocument2 paginiIn Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 11Document1 paginăHere's One Spring 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Summer 10Document1 paginăHere's One Summer 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boundary Issues (7) : Drawing The LineDocument1 paginăBoundary Issues (7) : Drawing The LineSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applying Choices and PossibilitiesDocument3 paginiApplying Choices and PossibilitiesSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tight Tan Slacks of Dezso Ban - Size and Strength - Fred Koch and Tudor BompaDocument4 paginiThe Tight Tan Slacks of Dezso Ban - Size and Strength - Fred Koch and Tudor BompaCD KHUTIYALEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bion and Primitive Mental States Trauma and The Symbiotic Link (Judy K. Eekhoff)Document159 paginiBion and Primitive Mental States Trauma and The Symbiotic Link (Judy K. Eekhoff)noseyatiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Almanac 2022-2023Document2 paginiAlmanac 2022-2023khatib mtumweniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barangay Council For The Protection of ChildrenDocument6 paginiBarangay Council For The Protection of ChildrenGem BesandeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 - 1 Intro 2 General Safety PracticesDocument3 pagini3 - 1 Intro 2 General Safety PracticesKevin Sánchez RodríguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operant Conditioning: - B F Skinner (1948)Document12 paginiOperant Conditioning: - B F Skinner (1948)AmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- OSH ProgrammingDocument29 paginiOSH Programmingmarlyn madambaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Newborn ExaminationDocument132 paginiThe Newborn ExaminationdevilstÎncă nu există evaluări

- MANIADocument1 paginăMANIALillabinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Health RisksDocument27 paginiAssessment of Health RisksMohamed GHAFFARÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 FP Client AssessmentDocument54 paginiModule 3 FP Client AssessmentJhunna TalanganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toolbox Talks - Near Miss ReportingDocument1 paginăToolbox Talks - Near Miss ReportinganaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HousekeepingDocument18 paginiHousekeepingমুসফেকআহমেদনাহিদÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Service Training Program Service Learning Program: Help The VulnerableDocument11 paginiNational Service Training Program Service Learning Program: Help The VulnerableBrunhild BangayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doctor'S Order and Progress NotesDocument3 paginiDoctor'S Order and Progress NotesDienizs LabiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Template Traffic Light MatrixDocument1 paginăTemplate Traffic Light MatrixDivalita100% (1)

- Classroom Activity CHCDIS003Document4 paginiClassroom Activity CHCDIS003Sonam GurungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blue Eyes Brown Eyes Nov 10 2021Document31 paginiBlue Eyes Brown Eyes Nov 10 2021Emmy S.U.Încă nu există evaluări

- Critical Analysis REBTDocument4 paginiCritical Analysis REBTMehar KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Detail of Rajiv Gandhi Jeevandayee Arogya Yojana MaharashtraDocument180 paginiDetail of Rajiv Gandhi Jeevandayee Arogya Yojana MaharashtraBrandon Bell100% (1)

- Banco de Preguntas ReabilitacionDocument19 paginiBanco de Preguntas ReabilitacionVanessa AlcantaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ramos Persuasive-Essay 3rdDocument3 paginiRamos Persuasive-Essay 3rdMa. Cassandra A. RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural ListDocument7 paginiCultural ListTilakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postnatal DepressionDocument36 paginiPostnatal DepressionMariam Matchavariani100% (1)

- Zoono Fact Sheet 53 - Comparison Between Dettol Hand Sanitiser and GermF...Document2 paginiZoono Fact Sheet 53 - Comparison Between Dettol Hand Sanitiser and GermF...Eileen Le RouxÎncă nu există evaluări