Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Space Between

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Space Between

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

COVER STORY: DIRECT THERAPY

The space

READ THIS IF YOU WANT TO EXPLORE THE SPACES BETWEEN WHAT A CLIENT CAN DO AND WHAT THEY CANT THERAPY DEMAND AND SUPPLY LINGUISTICS AND SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY

no rehearsal, a week later Jason again said it correctly. The therapy implication was obvious. I decided to try it out with more children.

Focusing treatment

At 4;6, Kelvin was mostly incomprehensible. As an example, using a large character in pointed brackets to show a weak articulation, cardigan went to with laterality in the final onset and dorsality in the nasal. By 5;3, when we started therapy, he was more understandable but still had issues. He could now say cardigan, except that the /g/ was . In one session I focused on the stop quality of the /g/. First I opened the final syllable, devoiced the onset, and changed the stress pattern to . Kelvin said this as , so I then tried a sonorant in the stressed onset, which Kelvin could say. After ten trials varying the two sonorants /n/ and /l/ in this position, Kelvin could say forms like with all three syllables beginning with an oral stop. If all the stops were voiceless became , so voicing had to be part of the issue. After two successful trials with a voicing contrast, I tried more dactylls, starting with , but varying the voicing and the length of the stressed vowel. After nine more successful trials, I closed the final syllable with /n/ as . This was correct. After was also correct, I returned to cardigan. This was now correct with three proper stops, two articulators and contrastive voicing in the middle. By 5;6, after just 14 half-hour sessions, with each session consisting of work around one or more different words, and with this as the sole therapy, Kelvins speech was age appropriate. Leo at 6;0 had the speech of a 4 year old. After 11 halfhour sessions over 3 months, following the same approach, with Leo saying around 1,000 nonsense words in all, bearing on a wide variety of relations between the stress pattern and the sound-structure, his speech was age-appropriate. This therapy starts from what the child can do, and builds on this, working towards what the child cant do. All responses get equal praise. The immediate goals are nonsense words, most said just once. The intention is for the child to experience non-stop success and to discover how features and prosody interact. I developed Feature Prosodic Therapy from 1983 to 1989 in NHS clinics with children with specifically phonetic / phonological disorders who were not responding to therapy on the basis of missing or defective sounds, or for whom there was no obvious therapy. It is still rudimentary and open to improvement.

Words like Geronimo and cardigan might not appear in standard articulation or phonology assessments, but for linguist and onetime speech and language therapist, Aubrey Nunes, they are key to the search for more effective and efficient therapy for children with speech disorders. Here, he explains the development and unexpected pedigree of feature prosodic therapy, where the child and therapist explore the space between what children can say and what they cant.

ack in 1983 a father referred his son to me. Jason, then aged seven, had had speech and language therapy and been discharged with the parents getting the idea that any remaining problems should resolve on their own. There were no problems with Jasons school work, but his father felt there were still issues with his speech. On assessment, Jason had a complete phonemic inventory, with no obvious problem in casual conversation, but he could say few words of four syllables or more (for in. At this level of stance, Geronimo became word-complexity, Jasons speech sounded immature. I remember the heady scent of elder in full bloom as I decided to accept Jason for treatment. It seems fitting now, given that we were embarking on a journey that would change my understanding of therapy and on the way pay tribute to the professions own unsung elders. So, what treatment? What caused which errors? I reasoned that the difference(s) between what Jason could and couldnt say would provide a basis for treatment. So I took a word Jason couldnt say, and changed it to something he could say. We continued this process, gradually moving closer to the target, until he could say it correctly. Each change produced a nonsense word, but a possible one nonetheless. This article describes what happened next. It is relevant to speech and language therapy for children with speech-specific issues mostly in mainstream. My aim is to enable therapists working with such children to: Sharpen diagnosis and focus treatment Raise clinical goals Ensure that the most severely affected children are treated accordingly Effect economies. Returning to Jason, starting from a variation of the target word that he could manage, I found I could ask him to say around 100 nonsense words in a session. I gave no correction, just praised his efforts regardless. My purpose was to define the point(s) at which the breakdown occurred and to find a way of working up to that point that would facilitate success. At the end of the first session I again asked Jason to say the original word, and he said it correctly. With no consultation and presumably

Pedigree

What I didnt know then was that such therapy has a pedigree. William Holder was a 17th century teacher of the deaf, John Thelwall treated childrens speech disorders in

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE SUMMER 2006

COVER STORY: DIRECT THERAPY

between

where the English stress rule is first fully spelt out. The one way in which Feature Prosodic Therapy may improve on the practice of the pioneers is that it involves an on-line adjustment by the therapist to the way the child is managing or not so as to ensure the child can copy whatever is being modelled by the therapist. Every therapy should be tested rigourously. I ran the first test of Feature Prosodic Therapy with otherwise normally-developing children, and then developed the theoretical rationale - see Nunes (2002). A clinically based pilot test is now in process and I welcome contact from any therapist who would like further information.

Process of learning

This approach is about therapy in relation to the process of learning. It is obvious that children are expected to learn in about 10 years what makes one language different from others. What is less obvious is that such differences are not random and that, despite the variety, there are universals. The first person to see this was Holder, with his early version of distinctive feature theory. Another universal concerns word-stress. If a language has a stress-system like about half the worlds languages do either it is just on the edge of the word or it is by an alternation between heavy and light beats in succeeding syllables. In the French hippopotame, the only stress is on the /a/. In English, as in French, the stress is computed from the right, and some final rimes are ignored, but there is an alternation of beats. So in hippopotamus, there is a light stress on the first syllable and main stress on the third. Because in English stress often falls on the initial syllable, there is an easy inference that scansion is from left to right. Such an inference happens to be correct in Scottish Gaelic but not in English, where stress is defined on three interacting principles: scansion from the right, alternating beats, and a skipping of some final syllables. This of course has to be learned. And it is not easy. There are many other ways in which stress could be organised - but isnt. It could peak in the middle of a word, or words could vary randomly according to whether they have stress or not. But no language like this has been found. Rather, stress is computed from left or right, with alternation or not, and so on. So the learner only needs to consider a particular sub-set of the logically possible options. Because this sub-set is finite, acquisition can be finite too. But in order for this to work, the learner must have a way of telling what counts as evidence and what does not. The simplest way of explaining this learnability is by a Speech and Language Acquisition Module (SLAM), interpreting for the child what they happen to hear. A defect in this module leads directly to a disorder of speech and / or language. This learnability-driven approach: Explains the (otherwise hard to explain) co-morbidities, involving lisps, multiple processes, the loss of vowel distinctions, and syntactic issues. Suggests that what speech and language therapy

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE SUMMER 2006

Cover photo by Paul Reid. Posed by models

the early 19th century, and Alexander Melville Bell treated communication issues in children and adults later in the 19th century. Holder (1669) proposed the essence of what is now known as distinctive feature theory with phonemes as the surface expression of combinations of universal features. Thelwall (1814) used an early version of what is now known as the metrical theory of word stress to describe the characteristic English alternation between stressed and unstressed syllables. Making distinctive feature theory more complete, Bell (1849) showed that English vowels could be defined by height and frontness / backness. As a Scot, Bell was interested in the difference between his trilled /r/ and the English untrilled /r/, and he proposed a feature for this. All three describe their work in terms which make it

easily recognisable as speech and language therapy. From Holder to Bell there is a growing understanding of the significance of linguistics. Significantly, these therapy pioneers all asked children to repeat structured sequences of minimally-different nonsense words. This fits in with the modern idea of possible words from generative phonology. The pioneers dont talk about possible words, as this term only came in during the 1960s, but it is only on the basis of this idea that their practice makes sense. The pioneers legacy was buried in the early 1900s and then lost until Rockey (1977) rediscovered some of it. Duchan and Nunes (forthcoming) find more. The legacy has been greatly advanced by studies of both prosody and distinctive features since Chomsky and Halle (1968),

COVER STORY: DIRECT THERAPY

DOES in such cases is to help a natural process in the childs mind of getting to know what counts as a possible sentence / word. Informs answers to questions like: Is my child braindamaged? Have we as parents done something wrong? If there is a Speech and Language Acquisition Module, the answer to both questions can be a firm no. The implications are both positive and negative. A) POSITIVE IMPLICATIONS: i) By Feature Prosodic Therapy a small but permanent gain can be made in 75% of children with speech specific issues saying between 20 and 100 nonsense words - In this first test of Feature Prosodic Therapy parents were not directly involved. The sole variable was the childrens experience of saying the selected nonsense words. For the sake of replicability, in a way that I would not do in the clinic, the sequence was standardised. - Because gains are by the interaction between elements, these are exponentially greater than by the sum of the sessions, and thus cost-effective. - Parents like to see session-by-session gains which are both permanent and exponential. ii) Diagnosis is sharpened - The diagnosis is defined in terms of the relation between normal competence and the childs speech. So in both cardigan as and Geronimo as , there are limits on which features can be realised outside the foot (underlined). Both of these forms could be described by combinations of processes - in , by a dorsal or back-ofthe-tongue gesture getting wrongly made in the final consonant, sonorance in the final consonant getting wrongly copied into the consonant before, but with a change from nasal to lateral, and so on. But this is mak-

ing the childs speech more complex than competent speech, so it doesnt explain anything. By diagnosing in terms of limits, it is possible to refer to both issues and achievements. This can be nicely and accurately put to parents, for example He / she can only say that back of the tongue bit of the sound at the end of the word. The key word is only. - A positive and non-pressurising speech and language therapy approach is underpinned. - There is a better chance of catching the most severely affected children. iii) If therapy goals are defined in relation to possible words, the long-term goal is likely to be normal speech - None of our elders suggests anything else. This is obviously a much higher goal than one defined on mere improvement or communicative need. B) NEGATIVE IMPLICATIONS There is no reason to: i) Assume that child-directed speech makes all the difference If it did, finite learnability would be impossible as explained earlier, this is contrary to fact. In particular cases, the style of parent-child interaction may be non-optimal and this may impair the process of acquisition. But it does not follow that such an effect is general. You may feel - for this and the other negative implications listed - there is proof-of-the-pudding evidence to the contrary from therapists experience. The problem, though, is telling what is causing what. For example, when parents are coached in the use of child-directed speech and improvement follows, was the child-directed speech the cause, or was it the change in the parents thinking and feelings about talking? ii) Characterise speech issues only by processes (stopping, fronting, initial consonant deletion, assimilation, and so on) The effect is that therapy goals are seen in terms of what is wrong / most difficult for the child. Common pronunciations like little as and soldier as are hard to describe. Complex, subtle and unfamiliar interactions between consonants and vowels can be underestimated and the most serious disorders overlooked or misread. The children concerned can fall through the net. iii) Expect sensori-motor treatments to have a general effect Shoppinglist definitions of speech-specific, or verbal, a/dyspraxia, have multiple (and contentious) secondary characteristics. Without excluding the possibility of a/dyspraxia in exceptional cases, the general treatment of mixed disorders in this way makes it hard to understand what they truly are. By working on sensori-motor issues in isolation, by certain software packages, by

Auditory Integration Training or by oral-motor therapy with its associated materials (approaches that have been marketed before being fully tested), there is a loss of diagnostic focus. iv) Allocate scarce resources by giving priority to younger children This risks diverting resources to minor issues which may resolve naturally, and may deny resources to children with greater issues. Phonetic / phonological development has an irreducible linguistic aspect, is developmentally vulnerable, and is still normally in process at 8;6. Since it is impossible to determine future needs in relation to a process before it is naturally complete, therapy resources should remain available to children of 8;6 and older. v) Expect to treat speech issues by anything other than face-to-face, expert therapy (or think that therapy is ever routine) Law et al. (1998) found that what they call indirect therapy does not work in the case of speech delays. By my claim, it cannot work. This is not to disparage the role of parents, assistants, teachers, volunteers, and others, as observers, helpers, and so on. But they cannot replace therapists. Some speech and language issues are unlikely to resolve spontaneously. Given the space between publiclyfunded therapy demand and supply, such issues deserve to be ring-fenced. Dr Aubrey Nunes is a linguist and director of Pigeon PostBox Ltd, which supplies computer-based educational toys (http://pigeonpostbox.co.uk), e-mail aubrey@pigeonpostbox.co.uk.

References

Bell, A. M (1849) A New Elucidation of the Principles of Speech and Elocution. Edinburgh: The author. Chomsky, N. & Halle, M. (1968) The Sound Pattern of English. New York: Harper Row. Duchan, J. & Nunes, A. (forthcoming) The Awesome Foursome. Holder, W. (1669) The Elements of Speech. London: Scholar Press. Law, J., Boyle, J., Harris, F., Harkness, A. & Nye, C. (1998) Screening for Speech and Language Delay: a Systematic Review of the Literature, Health Technological Assessment 2(9). Nunes, A. (2002) The Price of a Perfect System: Learnability and the Distribution of Errors in the Speech of Children Learning English as a First Language. PhD thesis University of Durham. Rockey, D. (1977) The logopaedic thought of John Thelwall, 1764-1834: First British speech therapist, British Journal of Disorders of Speech 12, pp. 83-95. Thelwall, J. (1814) Results of Experience in the Treatment of Cases of Defective Utterance London: J. McCreery. SLTP

Alexander Melville Bell (Parks Canada / Alexander Graham Bell Historic Site of Canada)

REFLECTIONS

DO I MAKE THE MOST OF MY LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE WHEN PLANNING THERAPY? DO I REGULARLY RE-VISIT ASSUMPTIONS OF HOW SERVICES SHOULD BE PROVIDED TO CHECK THEY HOLD GOOD? DO I SET CLINICAL GOALS TO SUIT THE CLIENT OR THE SERVICE?

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE SUMMER 2006

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Voice Unearthed: Hope, Help and a Wake-Up Call for the Parents of Children Who StutterDe la EverandVoice Unearthed: Hope, Help and a Wake-Up Call for the Parents of Children Who StutterÎncă nu există evaluări

- How I Used A Systematic Approach (2) : Phonology - Never Too Soon To StartDocument2 paginiHow I Used A Systematic Approach (2) : Phonology - Never Too Soon To StartSpeech & Language Therapy in Practice100% (1)

- Learn Spanish For Beginners Complete Course (2 in 1): 33+ Language Lessons- 10 Short Stories, 1000+ Phrases& Words, Grammar Mastery, Conversations& Intermediate Vocabulary AcceleratorDe la EverandLearn Spanish For Beginners Complete Course (2 in 1): 33+ Language Lessons- 10 Short Stories, 1000+ Phrases& Words, Grammar Mastery, Conversations& Intermediate Vocabulary AcceleratorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solution Manual For Communication Disorders Casebook The Learning by Example 0205610129Document4 paginiSolution Manual For Communication Disorders Casebook The Learning by Example 0205610129Gregory Robinson100% (30)

- Teach your child to speak - A manual for parents (translated)De la EverandTeach your child to speak - A manual for parents (translated)Încă nu există evaluări

- Stage 5 PDFDocument16 paginiStage 5 PDFkakaÎncă nu există evaluări

- StoryFrames: Helping Silent Children to Communicate across Cultures and LanguagesDe la EverandStoryFrames: Helping Silent Children to Communicate across Cultures and LanguagesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phonological and Lexical DevelopmentDocument12 paginiPhonological and Lexical DevelopmentMinigirlÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSD 146: Clinical ObservationDocument8 paginiCSD 146: Clinical ObservationBriana VincentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spanish for Medical Professionals With Essential Questions and Responses Vol 1: A Cheat Sheet Of Medical Spanish Vocabulary, Phrases And Conversational Dialogues For Medical ProvidersDe la EverandSpanish for Medical Professionals With Essential Questions and Responses Vol 1: A Cheat Sheet Of Medical Spanish Vocabulary, Phrases And Conversational Dialogues For Medical ProvidersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disability Research Assignment 3Document10 paginiDisability Research Assignment 3api-710206481Încă nu există evaluări

- English for Execs: And Everyone Who Desires to Use Good English and Speak English Well!De la EverandEnglish for Execs: And Everyone Who Desires to Use Good English and Speak English Well!Încă nu există evaluări

- Psycholinguistics Assignment 2 PDFDocument5 paginiPsycholinguistics Assignment 2 PDFFatima MunawarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coursebook - Part 1 PDFDocument20 paginiCoursebook - Part 1 PDFhieuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Changing Seasons: A Language Arts Curriculum for Healthy Aging, Revised EditionDe la EverandChanging Seasons: A Language Arts Curriculum for Healthy Aging, Revised EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stages of First Lang AcquisitionDocument10 paginiStages of First Lang AcquisitionKaye Payot-OmapasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hello, Dear StudentsDocument18 paginiHello, Dear Studentsmairaj2Încă nu există evaluări

- What Is The Approach in The Teaching of English As Second Language?Document10 paginiWhat Is The Approach in The Teaching of English As Second Language?AndresFelipeEspinosaZuluagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Name: Kevin Ameraldo Abrar Class: VI C NPM: A1B017082Document3 paginiName: Kevin Ameraldo Abrar Class: VI C NPM: A1B017082Kevin AmeraldoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theories of Language AcquisitionDocument43 paginiTheories of Language AcquisitionIsa ZaidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parents and Children Together (PACT) : Principle FoundationDocument2 paginiParents and Children Together (PACT) : Principle FoundationAmanda Calsolari de SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module Elt (Methodology)Document126 paginiModule Elt (Methodology)SyafqhÎncă nu există evaluări

- El 103 Module 4 MidtermDocument3 paginiEl 103 Module 4 MidtermRHEALYN DIAZ100% (1)

- Engage: DATE:03-30-21 Name:Ma - Lorena Akol Program&Section:Ba English 1EDocument32 paginiEngage: DATE:03-30-21 Name:Ma - Lorena Akol Program&Section:Ba English 1EMa. Lorena AkolÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20 APPI Conference 2006 "20 Years of Challenges and Decisions"Document15 pagini20 APPI Conference 2006 "20 Years of Challenges and Decisions"Katie ChauvinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speaking Portuguese As My First Language I Struggled Pronouncing Some Words in English CorrectlyDocument4 paginiSpeaking Portuguese As My First Language I Struggled Pronouncing Some Words in English Correctlylinh nguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychology Cognitive Science LinguisticsDocument12 paginiPsychology Cognitive Science Linguisticsmart0sÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 3: Phonology 2 - Phonemic AwarenessDocument12 paginiUnit 3: Phonology 2 - Phonemic AwarenessJonny xiluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engl104 Lesson 7Document14 paginiEngl104 Lesson 7Jenipher AbadÎncă nu există evaluări

- PART C-LitDocument4 paginiPART C-LitLeslie Grace AmbradÎncă nu există evaluări

- Felt 1 Module - Week 4Document4 paginiFelt 1 Module - Week 4RoanneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solution Manual For Communication Disorders Casebook The Learning by Example 0205610129Document35 paginiSolution Manual For Communication Disorders Casebook The Learning by Example 0205610129mimefuchsiaujnax100% (41)

- Portfolio Second Language AcquisitionDocument35 paginiPortfolio Second Language Acquisitionanon_869555093Încă nu există evaluări

- PED 101 Module 2 Lesson 2 R. AlamedaDocument18 paginiPED 101 Module 2 Lesson 2 R. AlamedaJulie Ann BillonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- General LinguisticsDocument5 paginiGeneral LinguisticsLina KurniawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- TEYL - Section BDocument19 paginiTEYL - Section BFlorence FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behaviorism MentalismDocument9 paginiBehaviorism MentalismThanh ThanhÎncă nu există evaluări

- NaturalísticoDocument17 paginiNaturalísticoLuiz FelipeÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Introduction To Psycholinguistics Week 4: Teacher: Zeineb AyachiDocument20 paginiAn Introduction To Psycholinguistics Week 4: Teacher: Zeineb AyachiZeineb Ayachi100% (3)

- Speech Production and ComprehensionDocument4 paginiSpeech Production and ComprehensionHaDIL Gaidi officielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comprehensible Input (Pictures, Knowledge of The World, Realia) Context Adquisition Vs Learning Focused Mode Vs Difuse Mode Index, Icon SymbolDocument3 paginiComprehensible Input (Pictures, Knowledge of The World, Realia) Context Adquisition Vs Learning Focused Mode Vs Difuse Mode Index, Icon SymbolMijael Elvis CVÎncă nu există evaluări

- My L1 Acquisition: "Knowledge of Languages Is The Doorway To Wisdom," Said Roger Bacon. So, I WonderDocument3 paginiMy L1 Acquisition: "Knowledge of Languages Is The Doorway To Wisdom," Said Roger Bacon. So, I WonderDyah AliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task 4 Diana Gutiérrez LuqueDocument3 paginiTask 4 Diana Gutiérrez LuqueDiana LuqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tema 2. Teorías Generales Sobre El Aprendizaje Y La Adquisición de Una Lengua Extranjera. El Concepto de Interlengua. El Tratamiento Del ErrorDocument12 paginiTema 2. Teorías Generales Sobre El Aprendizaje Y La Adquisición de Una Lengua Extranjera. El Concepto de Interlengua. El Tratamiento Del ErrorJose S HerediaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching My High-Functioning Autistic Piano StudentDocument3 paginiTeaching My High-Functioning Autistic Piano StudentChristine ChanÎncă nu există evaluări

- BLB - New Book 5Document95 paginiBLB - New Book 5drmohaddes hossainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Student Work - Asw p1 311Document21 paginiAnalysis of Student Work - Asw p1 311api-454711641Încă nu există evaluări

- Mantra TraDocument134 paginiMantra Tralyesss2150% (2)

- Name: Yana, Mary Ann C. ELT 211 First Examination: This Examination Paper Essay Is Just Based On What I UnderstandDocument4 paginiName: Yana, Mary Ann C. ELT 211 First Examination: This Examination Paper Essay Is Just Based On What I UnderstandManna YanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Well Beyond The BasicsDocument3 paginiWell Beyond The BasicsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating Music Therapy Services and Speech-Language Therapy Services For Children With Severe Communication Impairments: A Co-Treatment ModelDocument4 paginiIntegrating Music Therapy Services and Speech-Language Therapy Services For Children With Severe Communication Impairments: A Co-Treatment ModelDiana LoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Total Phsyical ResponseDocument9 paginiTotal Phsyical ResponseDwi QatrunnadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Now Brown CowDocument133 paginiHow Now Brown CowMaciek Angelewski100% (2)

- ABANAS M4L4 WorksheetDocument3 paginiABANAS M4L4 WorksheetCharlynjoy AbañasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psycholinguistics and Its TheoriesDocument8 paginiPsycholinguistics and Its TheoriesDr-Mubashar AltafÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clear Speech Practical Speech Correction and Voice Improvement, 4th Edition PDFDocument90 paginiClear Speech Practical Speech Correction and Voice Improvement, 4th Edition PDFSachin Shinkar100% (11)

- Behavioristic Approach: First Language Acquisition TheoryDocument31 paginiBehavioristic Approach: First Language Acquisition TheoryFrance LomerioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Turning On The SpotlightDocument6 paginiTurning On The SpotlightSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imprints of The MindDocument5 paginiImprints of The MindSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Document78 paginiMount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Speech & Language Therapy in Practice75% (8)

- Winning Ways (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Summer 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Summer 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talking Mats: Speech and Language Research in PracticeDocument4 paginiTalking Mats: Speech and Language Research in PracticeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Winter 2007)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Winter 2007)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Document1 paginăIn Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One SPR 09 Friendship ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One SPR 09 Friendship ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 09) Speed of SoundDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 09) Speed of SoundSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Autumn 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Autumn 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowDocument1 paginăHere's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Summer 10Document1 paginăHere's One Summer 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 10) Acknowledgement, Accessibility, Direct TherapyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 10) Acknowledgement, Accessibility, Direct TherapySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Aut 09 Communication Tree, What On EarthDocument1 paginăHere's One Aut 09 Communication Tree, What On EarthSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ylvisaker HandoutDocument20 paginiYlvisaker HandoutSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 11Document1 paginăHere's One Spring 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Document2 paginiIn Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Winter 10Document1 paginăHere's One Winter 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applying Choices and PossibilitiesDocument3 paginiApplying Choices and PossibilitiesSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalDocument2 paginiIn Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practical FocusDocument2 paginiA Practical FocusSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boundary Issues (7) : Drawing The LineDocument1 paginăBoundary Issues (7) : Drawing The LineSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parkinsons Presentation Case StudyDocument33 paginiParkinsons Presentation Case Studyapi-287759747Încă nu există evaluări

- PhilHealth Circular No. 14 S. 2018 - CF4Document3 paginiPhilHealth Circular No. 14 S. 2018 - CF4Toche Doce100% (1)

- Director, Office of Workers' Compensation Programs, United States Department of Labor v. August Mangifest, 826 F.2d 1318, 3rd Cir. (1987)Document27 paginiDirector, Office of Workers' Compensation Programs, United States Department of Labor v. August Mangifest, 826 F.2d 1318, 3rd Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reasons For Extraction of Primary Teeth in Jordan-A Study.: August 2013Document5 paginiReasons For Extraction of Primary Teeth in Jordan-A Study.: August 2013Mutia KumalasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Regenerative Interventional Approach To The Management of Degenerative Low Back PainDocument16 paginiA Regenerative Interventional Approach To The Management of Degenerative Low Back PainAthenaeum Scientific PublishersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pediatric Physiology 2007Document378 paginiPediatric Physiology 2007Andres Jeria Diaz100% (1)

- Medical Surgical Nursing Nclex Questions Integu2Document12 paginiMedical Surgical Nursing Nclex Questions Integu2dee_day_8100% (2)

- Khalil High Yeild Step 2 Cs Mnemonic 2nd EdDocument24 paginiKhalil High Yeild Step 2 Cs Mnemonic 2nd EdCarolina Lopez100% (1)

- Fascio LaDocument20 paginiFascio LaMuhammad NoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bentley Autopipe v8 CrackDocument3 paginiBentley Autopipe v8 CrackAdi M. Mutawali100% (2)

- Health Policy Memo MgenoviaDocument5 paginiHealth Policy Memo Mgenoviaapi-302138606Încă nu există evaluări

- +bashkir State Medical UniversityDocument2 pagini+bashkir State Medical UniversityCB SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FCBDocument26 paginiFCBsprapurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation Checklist Case 7 Bronchial AsthmaDocument7 paginiEvaluation Checklist Case 7 Bronchial AsthmaChristian MendiolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Be Happy Healthy Wealthy SAMPLEDocument30 paginiBe Happy Healthy Wealthy SAMPLERosie GonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

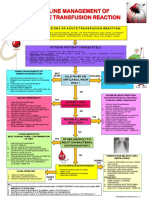

- Transfusion Reaction PDFDocument1 paginăTransfusion Reaction PDFKah Man GohÎncă nu există evaluări

- GB 21 PDFDocument2 paginiGB 21 PDFray72roÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Essay NegligenceDocument3 paginiChapter 1 Essay NegligenceVladimir Hechavarria100% (1)

- CD4 Count CutDocument51 paginiCD4 Count Cutibrahim 12Încă nu există evaluări

- A Case of Paediatric CholelithiasisDocument4 paginiA Case of Paediatric CholelithiasisHomoeopathic PulseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Circulatory SystemDocument5 paginiCirculatory SystemMissDyYournurse100% (1)

- Impact of School Health Education Program On PersonalDocument4 paginiImpact of School Health Education Program On Personalaspiah mahmudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avicenna's Canon of MedicineDocument8 paginiAvicenna's Canon of MedicinelearnafrenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Langerhans-Cell Histiocytosis: Review ArticleDocument13 paginiLangerhans-Cell Histiocytosis: Review ArticleHanifah ArroziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maquet Meera BrochureDocument16 paginiMaquet Meera BrochureFeridun MADRANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pemanfaatan Teknik Assisted Hatching Dalam Meningkatkan Implantasi EmbrioDocument10 paginiPemanfaatan Teknik Assisted Hatching Dalam Meningkatkan Implantasi EmbrioMumutTeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 Hip Replacement SurgeryDocument13 pagini10 Hip Replacement SurgeryDIA PHONG THANGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Turkey Tail MushroomDocument10 paginiTurkey Tail Mushroomjuanitos111100% (2)

- Skin Care Plan: Nu Derm Protocol ForDocument7 paginiSkin Care Plan: Nu Derm Protocol ForsheilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- E-Exercise Book: Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS)Document10 paginiE-Exercise Book: Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS)Zia Ur RehmanÎncă nu există evaluări